Abstract

Background

This study examined prospective associations between atypical working hours with subsequent tobacco, cannabis and alcohol use as well as sugar and fat consumption.

Methods

In the French population-based CONSTANCES cohort, 47,288 men and 53,324 women currently employed included between 2012 and 2017 were annually followed for tobacco and cannabis use. Among them, 35,647 men and 39,767 women included between 2012 and 2016 were also followed for alcohol and sugar and fat consumption. Three indicators of atypical working hours were self-reported at baseline: working at night, weekend work and non-fixed working hours. Generalized linear models computed odds of substance use and sugar and fat consumption at follow-up according to atypical working hours at baseline while adjusting for sociodemographic factors, depression and baseline substance use when appropriate.

Results

Working at night was associated with decreased smoking cessation and increased relapse in women [odds ratios (ORs) of 0.81 and 1.25], increased cannabis use in men [ORs from 1.46 to 1.54] and increased alcohol use [ORs from 1.12 to 1.14] in both men and women. Weekend work was associated with decreased smoking cessation in women [ORs from 0.89 to 0.90] and increased alcohol use in both men and women [ORs from 1.09 to 1.14]. Non-fixed hours were associated with decreased smoking cessation in women and increased relapse in men [ORs of 0.89 and 1.13] and increased alcohol use in both men and women [ORs from 1.12 to 1.19]. Overall, atypical working hours were associated with decreased sugar and fat consumption.

Conclusions

The potential role of atypical working hours on substance use should be considered by public health policy makers and clinicians in information and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Substance use are the first preventable cause of premature death worldwide [1]. If left untreated, they could lead to somatic disorders (e.g., cancers and cardiovascular disorders) [2, 3], psychiatric disorders (e.g., mood disorders and suicide) [4,5,6,7] and social deprivation including occupational issues (e.g., absenteeism, work accident and job loss) [8, 9]. Sugar and fat overconsumption are also highly prevalent in western countries, and they share common vulnerability factors with substance use [10].

Substance use and sugar and fat consumption could be driven by occupational factors [11]. For instance, work stress and high job demand may increase the likelihood of substance use and relapse in former users [12, 13]. The number of workers having atypical hours is increasing [14, 15]. Among the different types of atypical working hours, the following ones may be particularly frequent: working at night, working on weekend (i.e., Saturdays and/or Sundays) and having non-fixed schedules [16]. In this study, we focused on atypical working hours and their associations with tobacco, cannabis and alcohol use and high sugar and fat consumption. Such working conditions have already been associated with a broad range of somatic, psychiatric and sleep disorders, as well as increased risk of work accidents [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

However, their potential consequences on substance use and sugar and fat consumption have not been examined yet, to the best of our knowledge. Since occupational health strategies exist to deal with atypical working hours at work, their benefits could be extended to decreasing the burden of such detrimental behaviors.

In a cross-sectional Spanish study on 3950 men and 3153 women aged 16–64 years, long working hours (i.e., 51–60 hours per week) were associated with higher odds of tobacco use in men and women compared to regular working hours [17]. In a meta-analysis conducted on alcohol use and long working hour, long working hours (i.e., more than 55 hours per week) were associated with alcohol use and new onset risky alcohol use in cross sectional studies [30]. Moreover, long working hours have been shown to be associated with time-related barriers to healthy eating, which in turn may be associated with unhealthy snacking and a higher sugar and fat consumption. For instance, in a cross-sectional study conducted on 2287 participants, working > 40 hours per week was associated with time-related barriers to healthful eating most among young adult men and among females working both part-time and > 40 hours per week [31]. In a longitudinal study, working at night was associated with higher odds of smoking among 488 male workers [32]. Regarding night work and nutrition patterns, some studies have reported frequent snack consumption and poorer diet quality [33, 34]. A study conducted among female nurses has shown that nurses with non-day shifts were more likely to have non-optimal eating behaviors which may contribute to an increased intake of saturated fat [35]. In addition, in a prospective study among airline workers, night shift was associated with higher percentage from total fat and saturated fats [36]. In a cross-sectional study on 3871 workers, those with permanent night work showed the highest odds of being overweight and having increased abdominal obesity [37, 38].

To our knowledge, no longitudinal study examined the association between atypical working hours and tobacco, cannabis, alcohol use as well as sugar and fat consumption in a large population-based sample of men and women, including a broad range of different atypical working hours (i.e., long working hours, working at night, non-fixed working hours) and while considering potential sociodemographic and clinical confounders. Hence, we took advantage of the French national population-based CONSTANCES cohort to examine prospectively the associations between atypical working hours and tobacco, cannabis, alcohol use and sugar and fat consumption in a large sample of workers from various social and occupational backgrounds [39]. Since patterns of substance use and occupational conditions usually differ according to sex, all these associations were examined in men and women separately [40, 41]. We hypothesized that atypical working hours would be associated with higher substance use and sugar and fat consumption.

Methods

Participants

The French population-based CONSTANCES cohort enrolled volunteers from 2012 to 2019, aged 18–69 years at baseline, according to a random sampling scheme stratified on age, gender, socioeconomic status, and region of France [39]. Among the different procedures conducted with participants, they completed annual self-administered questionnaires on their lifestyle, health, social, and personal characteristics. Additionally, they underwent physical examination in health-screening centers. The response rate at enrollment in the CONSTANCES cohort was of 7.3% [42], thus, in line with other international cohorts (e.g., 5.5% for the UK Biobank) [43]. All the procedures are detailed at www.constances.fr.

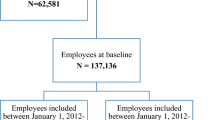

The main CONSTANCES cohort consists of a total of 199,717 volunteers enrolled between January 6, 2012, and January 8, 2020. However, according to the present study’s aims, those who were not employed at baseline (n = 62, 581) were not included. In addition, since outcomes were available at different periods of follow-up, individuals included after January 1, 2018 (n = 36,524) were excluded when studying the tobacco and cannabis outcomes, to allow for one-year of follow-up duration (since the last follow-up date of these outcomes was in 2018 at the time the present study was conducted). Regarding alcohol and sugar and fat outcomes, volunteers included after January 2017 (n = 61,722) were excluded since the last available follow-up endpoint was in 2017 for these outcomes. Data on sugar and fat was available only at baseline and at follow-up in 2017. Hence, a total of 47,288 men and 53,324 women participants were included for studying tobacco and cannabis use. Among them, a total of 35,647 men and 39,767 women were included for studying alcohol use and sugar and fat consumption (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Atypical working hours (exposures assessed at baseline)

Based on seven ‘Yes/No’ questions on atypical working hours that were analyzed separately, three different types of indicators were built.

First, night shifts were assessed based on the following questions: ‘Do you have (or have you had) work and travel times requiring you not to sleep at night for at least 50 days per year?’ and ‘Do you have (or have you had) work and travel times requiring you to go to bed after midnight for at least 50 days per year?’

Second, weekend work was assessed based on the following questions: ‘Do you work (or have you worked) more than one in two Sundays during the year?’ and ‘Do you work (or have you worked) more than one in two Saturdays during the year?’

Since the above questions were lifetime exposures to night shifts and week work and our main objective was to study the baseline atypical working hours, we selected only individuals who were currently exposed at baseline based on their date of exposure.

Third, non-fixed working hours were assessed based on the following questions that were only addressed to individuals who had a current job at baseline: ‘Do you work the same number of hours each day?’; ‘Do you work the same number of days each week?’ and ‘Do you work fixed hours?’

Answering “Yes” to any of the first four questions and “No” to any of the last three questions was considered as having a job with atypical working hours.

Even if we chose to give arbitrarily a label to identify three patterns of exposures to simplify the reading (i.e., “night shifts”, “weekend work”, “non-fixed working hours”), each exposure had to be studied separately since these exposures have been associated with different socio-occupational conditions and different health consequences, even within the same pattern [44,45,46].

Substance use and diet rich in sugar and fat (outcomes assessed at follow-up)

Tobacco use

Since the initiation of tobacco use almost always preexist to adulthood [47, 48], we focused on changes in tobacco use at follow-up among ever users (i.e., being a former or a current user at baseline). Precisely, the following indicators were computed:

-

Relapse of tobacco use among former smokers at baseline, i.e., reporting being a current smoker at follow-up while reporting being a former smoker at baseline.

-

Changing smoking status at follow-up among ever smokers at baseline, defined as participants who were ex-smokers or current smokers at baseline, irrespective of their current or past level of consumption. Thus, this outcome had four categories as follows: current smokers at baseline and remained current smokers at follow-up (reference category), current smokers at baseline and stopped smoking at follow-up, ex-smokers at baseline and remained ex-smokers at follow-up and ex-smokers at baseline and relapsed at follow-up.

Cannabis use

Since the initiation of cannabis use almost always preexist to adulthood [48], we focused on ever-users (i.e., participants who reported having ever used cannabis during their lifetime at baseline). Due to restricted sample size compared to tobacco use, we computed only the following indicator in three categories reflecting cannabis use at follow-up: former user, cannabis user of less than once a month, cannabis user at least once per month.”

Alcohol use

Since becoming alcohol abstainers is a rare phenomenon at a population level at least in France [49], we focused only on alcohol consumption categories at follow-up based on the World Health Organization (WHO) risk level classification (World Health Organization, 2000) as follows: low risk (1–27 drinks/week in men and 1–13 in women), no use, and at risk (≥28 drinks/week in men and ≥ 14 in women).

Diet rich in sugar and fat

Diet rich in sugar and fat was assessed using the 32-item qualitative food frequency questionnaire. This questionnaire was designed to reflect the intake in the French population and data regarding nutritional intake in the CONSTANCES cohort has already been published [50, 51]. The selected food items are compliant with the nutritional guidelines from the French National Nutrition and Health Program (PNNS) [52]. These items represented the weekly frequency of the consumed food (i.e., sugar, meat, cheese, yogurt, and others) on a scale from 0 to 4 with 0 being ‘never or nearly never’ and 4 ‘4 to 6 times per week’. Because food frequency was not normally distributed, each item’s square root was calculated and entered into a principal component analysis in order to identify and compute factors underlying the dietary patterns of the population [51]. Three factors were generated: diet rich in sugar and fat which was our variable of interest, traditional diet and diet rich in low fat protein (Supplementary Table S2). Diet rich in sugar and fat was assessed as quartiles variables: the first quartile which was the reference group corresponded to the lowest sugar and fat consumption and the fourth quartile to the highest consumption.

Covariates at baseline

Sociodemographic factors included age, occupational grade (low: manual and clerical; medium: technical; high: managerial positions), educational level and household income. Educational level and household income were assessed using self-reported questions on the highest obtained diploma based on the International Standard Classification of Education 2011 [53], and on total household net monthly income, respectively. Since these two variables were ordinal representation of underlying sets of continuous units, they were used as continuous variables.

Depression was assessed using the presence of a treated depression as reported by the physician during the medical exam at inclusion and treated as a binary variable (‘Yes’ versus ‘No’).

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear regressions were computed to study the associations between the indicators of atypical working hours (exposures) and tobacco, cannabis, alcohol use and diet rich in sugar and fat (outcomes). In other terms, binary logistic regressions were computed to study the associations between these indicators and relapse of tobacco use. Multinominal logistic regressions were computed to study the association between the exposures and sugar and fat intake as well as changing statuses in tobacco use, cannabis relapse. The associations between these indicators, tobacco and cannabis were studied until 2018 which was the last follow-up endpoint. Whereas the associations between these indicators, alcohol and diet rich in sugar and fat were studied until the last available follow-up endpoint which was in 2017. All the analyses were stratified by sex.

After computing univariable analyses, fully-adjusted models were performed including all the covariables mentioned above in addition to the baseline level of consumption for the substance chosen as the outcome. Regarding the baseline level of substance consumption, we adjusted for it for alcohol use and diet rich in sugar and fat. However, we did not adjust for it for tobacco and cannabis use since this variable was already included in the outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses were performed as supplementary analyses:

-

First, since job type could be associated with the aforementioned outcomes, we tested for statistical interactions between occupational grade and indicators of atypical working hours. We further examined the association between these indicators and outcomes in stratified analyses according to occupations. Occupations were categorized in four groups: ‘Farmers, blue-collar workers and craftsmen’; ‘Clerks’; ‘Intermediate workers’ and ‘Executives’.

-

Second, since the associations between each atypical working hours indicator and fat and sugar dietary patterns may be more pronounced among individuals with a lifestyle involving specific eating behaviors (e.g., sedentary lifestyle, currently on a diet, high physical activity), interactions between atypical working hours and BMI (< 25; ≥25 and < 30; ≥30), physical activity (score from 1 to 6, 0: not active and 6: very active) and being currently on diet (‘Yes’; ‘No’) were tested.

-

Third, since duration of exposure could play a role in the associations between atypical working hours and substance, theses associations were stratified by duration of exposure when information was available (i.e., the exposures related to night shifts (‘do you have (or have you had) work and travel times requiring you not to sleep at night for at least 50 days per year?’; ‘do you have (or have you had) work and travel times requiring you to go to bed after midnight for at least 50 days per year?’) and weekend work (‘do you work (or have you worked) more than one in two Saturdays during the year?’; ‘do you work (or have you worked) more than one in two Sundays during the year?’)). To measure the duration of exposure, we used the difference between the first date of exposure and the last date of exposure.

Missing data were handled by multiple imputations [54].

All p-values were two-sided with an α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were undertaken using the SAS system software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 47,288 men and 53,324 women included in 2012–2017, and of the 35,647 men and 39,767 women included in 2012–2016 are summarized in Table 1.

Compared to workers that were not exposed to atypical working hours, both men and women with atypical working hours were older, had a higher prevalence of low occupational grade and had a lower prevalence of high education or income. Depression was associated with several indicators of atypical working hours with more frequent associations in men than in women (Supplementary Tables S3, S4, S5 and S6).

Association between working at night, substance use and diet rich in sugar and fat (Table 2)

Tobacco use

Working after midnight was associated with increased odds of relapse in women that were former smokers (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.25, 95%CI: 1.09–1.43). In women that were current smokers at baseline, both working all night and after midnight were associated with decreased odds of quitting (aOR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.77–0.96 and aOR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.84, respectively).

Cannabis use

In men who were not cannabis users for the last 12 months, working all night and after midnight were associated with increased odds of using cannabis at least once per month at follow-up (aOR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.07–2.23 and aOR:1.40, 95%CI: 1.02–1.91, respectively).

Alcohol use

Working after midnight was associated with increased odds of alcohol use in both women and men (aOR: 1.14, 95%CI: 1.05–1.24 and aOR:1.12, 95%CI: 1.02–1.91, respectively).

Diet rich in sugar and fat

Working all night was associated with a decreased odd of consuming a diet rich in sugar and fat in men (aOR:0.86, 95%CI: 0.78–0.95 for the fourth quartile compared to the first). Similar results were found for working after midnight in both men and women (aOR: 0.91, 95%CI: 0.95–0.98 and aOR: 0.91, 95%CI: 0.83–0.99, respectively).

Association between weekend work, substance use and diet rich in sugar and fat (Table 3).

Tobacco use

In women that are current smokers at baseline, Sunday work was associated with decreased odds of quitting (aOR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.80–0.99). In both women and women, Saturday work was associated with decreased odds of quitting (aOR: 0.93, 95%CI: 0.87–0.98 and aOR: 0.92, 95%CI: 0.86–0.99, respectively).

Cannabis use

No significant association was found between weekend work and cannabis use.

Alcohol use

In women, Sunday work was associated with increased odds of alcohol use (aOR: 1.09, 95%CI: 1.02–1.18).

Saturday work was associated with increased odds of alcohol use in both women and men (aOR: 1.14, 95%CI: 1.07–1.22 and aOR: 1.13, 95%CI: 1.03–1.24, respectively).

Diet rich in sugar and fat

Sunday work was associated with a decreased odd of consuming a diet rich in sugar and fat in men (aOR:0.80, 95%CI: 0.75–0.87 for the fourth quartile compared to the first). Similar results were found for Saturday work in both men and women (aOR: 0.85, 95%CI: 0.80–0.92 and aOR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.80–0.99, respectively).

Association between non-fixed working hours, substance use and diet rich in sugar and fat (Table 4).

Tobacco use

In current smokers at baseline, fluctuating number of working hours and working days were associated with decreased odds of quitting in both men and women (aOR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.78–0.89 and aOR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.86–0.98; aOR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.81–0.94 and aOR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.84–0.97, respectively).

Cannabis use

No significant association was found between non-fixed working hours and cannabis use.

Alcohol use

Fluctuating number of working hours and working days were associated with increased odds of alcohol use in both men and women (aOR: 1.15, 95%CI: 1.05–1.26 and aOR: 1.14, 95%CI: 1.06–1.23; aOR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.06–1.32 and aOR: 1.12, 95%CI: 1.02–1.22, respectively).

Diet rich in sugar and fat

No significant associations between non-fixed working hours and diet rich in sugar and fat were found.

Sensitivity analyses

The stratified analyses showed that the associations between atypical working hours and substance use were more pronounced in workers from low occupational grade compared to those from high occupational grade. In addition, most of these associations persisted in workers exposed since less than 1 year compared to individuals exposed since at least 1 year (data not shown).

No interactions were found between atypical working hours and BMI, physical activity or following a current diet when examining the associations between atypical working hours and diet rich in fat or sugar (data not shown).

Discussion

This study examined the prospective associations between atypical working hours at work and tobacco, cannabis, alcohol use, and a diet rich in sugar and fat among workers from a large population-based cohort while taking into account sociodemographic factors and depression. Overall, working at night was associated with decreased smoking cessation and increased relapse in women, increased cannabis use in men and increased alcohol use in both men and women. Weekend work was associated with decreased smoking cessation in women and increased alcohol use in both men and women. Non-fixed hours was associated with decreased smoking cessation in women and increased relapse in men and increased alcohol use in both men and women. Overall, atypical working hours were associated with decreased sugar and fat consumption.

This study has some strengths. First, the CONSTANCES cohort is a national population-based cohort from various sociodemographic and occupational conditions [39]. Second, we had the necessary data to adjust the analyses for potential confounders, and sufficient power to run stratified analyses by sex. Third, we had different questions to assess atypical working hours and the use of several substances and dietary intake. However, this study has some limitations. First, although the CONSTANCES cohort is a large population-based cohort with different work settings, randomly selected participants were included and followed on a voluntary basis are thus not representative of the general population. In addition, data were not weighted as it is usually done in large cohorts such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) while aiming at examining the relations between several variables rather than computing representative prevalence [55, 56]. In particular, most of the participants had a favorable social context, and they are more interested in their health. Thus, our results should be extrapolated with caution to other settings. Second, when dealing with substance use, participants tend to underestimate their consumption in relation with social desirability; hence, there is a risk of an under-estimation which is a common method bias [57]. Third, even if we had a large set of sociodemographic and clinical factors for considering potential confounding effects in order to examine longitudinal associations, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding due to unmeasured factors such as personality traits, or other exposure and socioeconomical factors. Thus, our findings, although computed from prospective analyses, must not be interpreted as causality pathways. Fourth, the absence of consumed quantities of fat and sugar intakes limited our ability to calculate energy intakes from these macronutrients and quantify their association with the indicators of atypical working hours. Fifth, we had one single measure of the exposures thus limiting our capacity to examine changes in the exposures before the assessment of the outcomes. Nevertheless, we examined changes in the associations according to the duration of the exposures for whom this information was available (i.e., night shifts and weekend work) and results showed that associations were more pronounced in individuals who were exposed for less than 1 year compared to those who were exposed for a longer period.” Sixth, in this present study, information on hours of sleep were not examined although this variable can be important to be taken into consideration while dealing with the associations between atypical working hours, substance use and diet rich in sugar and fat. Thus, future studies should plan to consider this variable in their models.

Working at night was associated with increased tobacco use in women, with increased cannabis use in men and with increased alcohol use in both men and women. Regarding alcohol use, this finding was not consistent with a previous published study that showed that working at night was associated with a decreased risk of being at risk [58]. Working at night could be associated with sleep disorders and fatigue [59]. Hence, workers who work at night might use these substances as sleep aids/hypnotic substances for sleep disorders or psychostimulants to overcome fatigue [60]. They might also use them to alleviate stress including psychological and work stress [61] since these individuals are more exposed to lack of peer support, as well as social and family conflicts (i.e., inter-marital tensions, imbalance in parenthood and household activities) [60]. Weekend work was associated with increased tobacco use in women and alcohol use in both men and women. Workers obliged to work on weekends have an increased likelihood of work-family conflicts compared to other workers [62]. Work-family conflicts are known to be associated with tobacco and alcohol use [63, 64]. Non-fixed working hours were associated with increased tobacco and alcohol use in both men and women. At least for some workers, non-fixed hours could increase time management autonomy (i.e., managing schedules and deadlines with minimum supervision). This situation has been associated with an increased level of work stress which could be associated with tobacco and alcohol use [65]. Moreover, since substance use are commonly associated with a decreased likelihood of finding a job [66], substance users might be oversampled in jobs that are usually less appealing, such as those requiring to work at night, on weekends or on non-fixed hours.

Stratified analyses suggested that the associations between atypical working hours and substance use may concern mainly workers from low occupational grade. This finding was consistent with the well-known increased vulnerability to substance use in workers from lower social positions [67]. Stratified analyses also suggested that the associations between atypical working hours and substance use may already appear among recently exposed workers. Although a healthy worker effect could be involved, these results could indicate that that it is probably not necessary to be exposed for a long time to observe a significant association with substance use.

Lastly, working after midnight and on Saturdays were associated with decreased sugar and fat consumption in both men and women. These work conditions might be associated with time-related barriers to eat and/or to buy food. As some atypical working hours such as night shifts are associated with a higher BMI level, the associations with atypical working hours and fat and sugar dietary patterns may be more pronounced among overweight or obese individuals or individuals following a current diet or individuals with a sedentary lifestyle. However, in the present study we failed to find significant interactions between BMI, physical activity, current diet and atypical working hours and in particular with working after midnight and on Saturdays. Moreover, we have analyzed the association between atypical working hours and fat and sugar intake by adding interaction terms in separate models with BMI, physical activity and following a particular diet in order to further explore whether our associations could be moderated by a third factor. However, interactions were not significant so it is unlikely in this study that different categories of BMI, physical activity or following or not a diet may have substantial roles in the associations between atypical working hours and fat and sugar intake. Otherwise, workers with healthier habits, including low sugar and fat intakes, might be more prone to engage themselves in jobs having high demand, such as those requiring to work after midnight or on Saturdays.

Conclusions

To conclude, these findings should be considered in health promotion programs and prevention strategies regarding poor health outcomes associated with atypical working hours. For workers who experience atypical hours, regular monitoring with standardized screening and early intervention on substance use are needed, even among those who are recently exposed and exposed to just one type of atypical hours. Our findings suggest that workers from low occupational grade may be more concerned. Longitudinal studies with more repeated measures should examine whether subtracting the workers exposed to working atypical working hours could decrease their risk of substance use. Furthermore, qualitative studies may be important to better understand the mechanisms that underlie these associations and the sex differences.

Availability of data and materials

Personal health data underlying the findings of our study are not publicly available due to legal reasons related to data privacy protection. However, the data are available upon request to all interested researchers after authorization of the French “Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés”. The CONSTANCES email address is contact@constances.fr.

GA declares personal fees from Pierre Fabre, Lundbeck, Zentiva and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. AD declares personal fees from his mentioned affiliations, Elsevier Masson, outside the submitted work. CL declares personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck and Otsuka Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work.

References

WHO. Global Health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1383–91.

Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38(5):613–9.

Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. The prevalence and impact of alcohol problems in major depression: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2005;118(4):330–41.

Wiesbeck GA, Kuhl HC, Yaldizli Ö, Wurst FM. Tobacco smoking and depression – results from the WHO/ISBRA study. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57(1–2):26–31.

Chen VC-H, Kuo C-J, Wang T-N, Lee W-C, Chen WJ, Ferri CP, et al. Suicide and other-cause mortality after early exposure to smoking and second hand smoking: a 12-year population-based follow-up study. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0130044.

Blanco C, Hasin DS, Wall MM, Florez-Salamanca L, Hoertel N, Wang S, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychiatric disorders: prospective evidence from a US National Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):388–95.

Shield KD, Rehm MX, Rehm J. Social costs of addiction in Europe. Impact of addictive substances and behaviours on individual and societal well-being; 2015. p. 181–8.

Morois S, Airagnes G, Lemogne C, Leclerc A, Limosin F, Goldberg S, et al. Daily alcohol consumption and sickness absence in the GAZEL cohort. Eur J Pub Health. 2017;27(3):482–8.

Goldberg M, Carton M, Descatha A, Leclerc A, Roquelaure Y, Santin G, et al. CONSTANCES: a general prospective population-based cohort for occupational and environmental epidemiology: cohort profile. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(1):66–71.

Kiepek N, Magalhães L. Addictions and impulse-control disorders as occupation: a selected literature review and synthesis. J Occup Sci. 2011;18(3):254–76.

Frone MR. Prevalence and distribution of illicit drug use in the workforce and in the workplace: findings and implications from a U.S. national survey. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(4):856–69.

Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158(4):343–59.

Algava E: Le travail de nuit en 2012. Essentiellement dans le tertiaire. 2014(DARES n 062, août).

Eurofound. Sixth European working conditions survey-overview report (2017 update). In: Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg; 2017.

Bihan BL, Martin C. Atypical working hours: consequences for childcare arrangements. Soc Policy Adm. 2004;38(6):565–90.

Artazcoz L, Cortès I, Escribà-Agüir V, Cascant L, Villegas R. Understanding the relationship of long working hours with health status and health-related behaviours. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(7):521–7.

Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;1:5–18.

Pease EC, Raether KA. Shift working and well-being: a physiological and psychological analysis of shift workers; 2019.

Parent M-É, El-Zein M, Rousseau M-C, Pintos J, Siemiatycki J. Night work and the risk of Cancer among men. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(9):751–9.

Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Kawachi I, et al. Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(11):825–8.

Chazelle E, Chastang J-F, Niedhammer I. Psychosocial work factors and sleep problems: findings from the French national SIP survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89(3):485–95.

Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG, et al. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2485–94.

Bara A-C, Arber S. Working shifts and mental health – findings from the British household panel survey (1995-2005). Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(5):361–7.

Fadel M, Sembajwe G, Gagliardi D, Pico F, Li J, Ozguler A, et al. Association between reported long working hours and history of stroke in the CONSTANCES cohort. Stroke. 2019;50(7):1879–82.

Yoon J-H, Jung PK, Roh J, Seok H, Won J-U. Relationship between long working hours and suicidal thoughts: Nationwide data from the 4th and 5th Korean National Health and nutrition examination survey. Plos One. 2015;10(6):e0129142.

Ervasti J, Pentti J, Nyberg ST, Shipley MJ, Leineweber C, Sørensen JK, et al. Long working hours and risk of 50 health conditions and mortality outcomes: a multicohort study in four European countries. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;11:100212.

Kivimäki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Singh-Manoux A, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386(10005):1739–46.

Humans IWGotIoCHt. IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. In: Night Shift Work. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. For more information contact publications@iarc.fr.

Virtanen M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Madsen IEH, Lallukka T, Ahola K, et al. Long working hours and alcohol use: systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies and unpublished individual participant data. BMJ. 2015;350:g7772.

Escoto KH, Laska MN, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ. Work hours and perceived time barriers to healthful eating among young adults. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(6):786–96.

Biggi N, Consonni D, Galluzzo V, Sogliani M, Costa G. Metabolic syndrome in permanent night workers. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25(2–3):443–54.

Peplonska B, Nowak P, Trafalska E. The association between night shift work and nutrition patterns among nurses: a literature review. Med Pr. 2019;70(3):363–76.

Lin T-T, Park C, Kapella MC, Martyn-Nemeth P, Tussing-Humphreys L, Rospenda KM, et al. Shift work relationships with same- and subsequent-day empty calorie food and beverage consumption. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;6:579–88.

Lin TT, Guo YL, Gordon CJ, Chen YC, Wu HC, Cayanan E, et al. Snacking among shiftwork nurses related to non-optimal dietary intake. J Adv Nurs. 2022;00:1–12.

Hemiö K, Lindström J, Peltonen M, Härmä M, Viitasalo K, Puttonen S. The association of work stress and night work with nutrient intake - a prospective cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(5):533–41.

Souza RV, Sarmento RA, de Almeida JC, Canuto R. The effect of shift work on eating habits: a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019;45(1):7–21.

Sun M, Feng W, Wang F, Zhang L, Wu Z, Li Z, et al. Night shift work exposure profile and obesity: baseline results from a Chinese night shift worker cohort. Plos One. 2018;13(5):e0196989.

Zins M, Goldberg M, Team C. The French CONSTANCES population-based cohort: design, inclusion and follow-up. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(12):1317–28.

Lohse T, Rohrmann S, Bopp M, Faeh D. Heavy smoking is more strongly associated with general unhealthy lifestyle than obesity and underweight. Plos One. 2016;11(2):e0148563.

Harrington JM. Health effects of shift work and extended hours of work. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(1):68–72.

Goldberg M, Carton M, Descatha A, Leclerc A, Roquelaure Y, Santin G, et al. CONSTANCES: a general prospective population-based cohort for occupational and environmental epidemiology: cohort profile. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(1):66–71.

Toledano MB, Smith RB, Brook JP, Douglass M, Elliott P. How to establish and follow up a large prospective cohort study in the 21st century - Lessons from UK COSMOS. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0131521.

Létroublon C, Daniel C: Le travail en horaires atypiques : quels salariés pour quelle organisation du temps de travail DARES Analyses 2018, 38.

Greubel J, Arlinghaus A, Nachreiner F, Lombardi DA. Higher risks when working unusual times? A cross-validation of the effects on safety, health, and work-life balance. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89(8):1205–14.

Brogmus GE. Day of the week lost time occupational injury trends in the US by gender and industry and their implications for work scheduling. Ergonomics. 2007;50(3):446–74.

Redonnet B, Chollet A, Fombonne E, Bowes L, Melchior M. Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drug use among young adults: the socioeconomic context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121(3):231–9.

Bernat DH, Klein EG, Forster JL. Smoking initiation during young adulthood: a longitudinal study of a population-based cohort. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(5):497–502.

Centre ICE. INSERM Collective Expert Reports. In: Alcohol: Social damages, abuse, and dependence. Paris: Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale; 2003. Copyright © 2003, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM).

Matta J, Czernichow S, Kesse-Guyot E, Hoertel N, Limosin F, Goldberg M, et al. Depressive symptoms and vegetarian diets: results from the CONSTANCES cohort. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1695.

Matta J, Hoertel N, Kesse-Guyot E, Plesz M, Wiernik E, Carette C, et al. Diet and physical activity in the association between depression and metabolic syndrome: CONSTANCES study. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:25–32.

Plessz M, Zins M, Czernichow S, Kesse-Guyot E. Les habitudes alimentaires dans la cohorte Constances : équilibre perçu et adéquation aux recommandations nutritionnelles françaises. Bulletin Epidemiologique Hebdomadaire. 2016;2016:660–6.

Schneider S. The international standard classification of education 2011. Comp Soc Res. 2013;30:365–79.

Newgard CD, Haukoos JS. Advanced statistics: missing data in clinical research--part 2: multiple imputation. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):669–78.

Gay IC, Tran DT, Paquette DW. Alcohol intake and periodontitis in adults aged ≥30 years: NHANES 2009-2012. J Periodontol. 2018;89(6):625–34.

Anderson ML, Chang BH, Kini N. Alcohol and drug use among deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals: a secondary analysis of NHANES 2013-2014. Subst Abus. 2018;39(3):390–7.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:539–69.

Cheng W-J, Härmä M, Koskinen A, Kivimäki M, Oksanen T, Huang M-C. Intraindividual association between shift work and risk of drinking problems: data from the Finnish public sector cohort. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78(7):465–71.

Costa G. Sleep deprivation due to shift work. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;131:437–46.

Direction de l’animation de la recherche des études et des statistiques (DARES): Le travail de nuit en 2012. 2014. Août 2014 N 062.

Conway PM, Campanini P, Sartori S, Dotti R, Costa G. Main and interactive effects of shiftwork, age and work stress on health in an Italian sample of healthcare workers. Appl Ergon. 2008;39(5):630–9.

Lass I, Wooden M. Weekend work and work–family conflict : evidence from Australian panel data. J Marriage Fam. 2021;84:250–72.

Nelson CC, Li Y, Sorensen G, Berkman LF. Assessing the relationship between work-family conflict and smoking. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1767–72.

Wang M, Liu S, Zhan Y, Shi J. Daily work-family conflict and alcohol use: testing the cross-level moderation effects of peer drinking norms and social support. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(2):377–86.

Azagba S, Sharaf MF. The effect of job stress on smoking and alcohol consumption. Health Econ Rev. 2011;1(1):15.

Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, Finger MS. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:350–3.

Amaro H, Sanchez M, Bautista T, Cox R. Social vulnerabilities for substance use: stressors, socially toxic environments, and discrimination and racism. Neuropharmacology. 2021;188:108518.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the team of the “Population-based Epidemiologic Cohorts Unit” (Cohortes en population) that designed and manages the Constances Cohort Study. They also thank the National Health Insurance Fund (“Caisse nationale d’assurance maladie”, CNAM) and its Health Screening Centres (“Centres d’examens de santé”), which are collecting a large part of the data, as well as the National Old-Age Insurance Fund (“Caisse nationale d’assurance vieillesse”, Cnav) for its contribution to the constitution of the cohort, ClinSearch, Asqualab and Eurocell, which are conducting the data quality control. Finally, the authors thank the “Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques” (DREES) and the “Direction de l’Animation de la recherche, des Études et des Statistiques” (DARES) which depend on the Ministry of Labour for their non-financial support to the present study.

Funding

NH was supported by a grant from the French Interministerial Mission for Combating Drugs and Addictive Behaviours (MILDECA). The CONSTANCES Cohort Study was supported and funded by the French National Health Insurance Fund (“Caisse nationale d’assurance maladie”, CNAM). The CONSTANCES Cohort Study is an “Infrastructure nationale en Biologie et Santé” and benefits from a grant from the French National Agency for Research (ANR-11-INBS-0002). CONSTANCES is also partly funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), AstraZeneca, Lundbeck and L’Oréal through Inserm-Transfert. None of these funding sources had any role in the design of the study, collection and analysis of data or decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NH, GA and JM designed the study. NH run the analyses. NH, GA and JM drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to the interpretation of the data, critically revised the draft of the work for important intellectual content and approved the final version. NH had the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

CONSTANCES has obtained the authorization of the National Data Protection Authority and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute for Medical Research (Authorization number 910486) and was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants signed an informed consent form to be included in the cohort.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1.

The distribution of employees by periods of follow-up.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table S2.

The principal component analysis of the qualitative food frequency questionnaire using the Varimax rotation.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S3.

Baseline characteristics of the employees by indicators of atypical working hours in men between 2012-2017.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table S4.

Baseline characteristics of the employees by indicators of atypical working hours in women between 2012-2017.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table S5.

Baseline characteristics of the employees by indicators of atypical working hours in men between 2012-2016.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table S6.

Baseline characteristics of the employees by indicators of atypical working hours in women between 2012-2017.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamieh, N., Airagnes, G., Descatha, A. et al. Atypical working hours are associated with tobacco, cannabis and alcohol use: longitudinal analyses from the CONSTANCES cohort. BMC Public Health 22, 1834 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14246-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14246-x