Abstract

Background

Transgender individuals are considered at high risk of contracting HIV infection. Integrating HIV testing and counseling (HTC) services into current transgender health programs is necessary to increase its uptake. Our study aimed to describe the characteristics of trans men (TM) and trans women (TW) who accessed HTC services in a community-based transgender health center in Metro Manila, Philippines, and to examine the relationship between gender identity and their non-uptake of HIV testing.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of TM and TW seeking care from 2017 to 2019. Medical records of clients were reviewed to ascertain their age, gender identity, year and frequency of clinic visits, lifestyle factors, and non-uptake of HIV testing. The effect of gender identity on the non-uptake of HIV testing was estimated using a generalized linear model with Poisson distribution, log link function, and a robust variance, adjusted for confounding variables.

Results

Five hundred twenty-five clients were included in the study, of which about 82.3% (432/525) of the clients declined the HTC services being offered. In addition, the prevalence of non-uptake of HIV testing was 48% higher (Adjusted Prevalence Ratio: 1.48; 95% Confidence Interval: 1.31–1.67) among TM compared to TW. Approximately 3.7% (1/27) and 10.6% (7/66) of the TM and TW, respectively, who accessed the HTC services were reactive. Moreover, most reactive clients were on treatment 87.5% (7/8); three were already virally suppressed, four were on ART but not yet virally suppressed, and one TW client was lost to follow up.

Conclusion

The non-uptake of HTC service of TM and TW is high. HIV program implementers should strategize solutions to reach this vulnerable population for increased and better HTC service uptake and linkage to care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The transgender population is recognized as an at-risk group for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) [1]. Across the world, a pooled HIV prevalence of 19.1% was reported for trans women (TW) [2]. Moreover, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2013 reported that in the 3.3 million HIV testing events conducted, the estimates of transgender individuals newly diagnosed with HIV were nearly three times the national average [3].

This increase in HIV/AIDS cases is consistent with multilevel drivers of HIV among the communities, including social stigma and discrimination [4]. Transgender people are reported to have significantly reduced lifetime rates of HIV testing relative to cisgender gay and bisexual men. Conversely, HIV testing rates are likely lower among transgender adolescents [5]. Increased levels of discrimination, such as denial of medical services and harassment in healthcare settings [6, 7] and expected discrimination, have been associated with postponement or delay of medical services among the transgender population [8, 9]. The current state of our society is directly inclining towards its conventional heteronormative behavior [10]. This ideology increases the vulnerabilities of transgender people to HIV/AIDS in the context of their behaviors, attitudes, and risk practices [11]. They are susceptible to disparities in better access to health, including non-availability of transgender health services, care refusal, substance abuse, and poor mental and sexual health outcomes [12]. This observation parallels narrowed options for their healthcare, such as gender affirmation services, preventive health screenings, and mental health interventions [13].

To address the HIV/AIDS burden, local HIV prevention programs that are trans-inclusive are increasing [14]. Strategies include HIV self-testing, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP), condoms and lube, and other biopsychosocial methods. Engagement in these programs and services will help mitigate the prevalence of HIV, suicide, and violence across the transgender community [15]. However, the Philippines, where resources are in scarcity, regrettably struggles to address the unique set of healthcare needs the transgender community requires. Moreover, the current healthcare system in the country does not necessarily function effectively for the transgender population, specifically for HIV testing and counseling (HTC) services. As a result, inclusive surveillance and data collection methods across the national transgender communities remain a challenge. Integrating the transgender population into the current Philippines HIV/AIDS surveillance system may modify this current state. Hence, it is essential to establish evidence to support the health outcomes of Filipino transgender people that will help inform program development and interventions explicitly targeted at this key population. Our study aimed to describe the characteristics of trans men (TM) and TW who accessed the community-based transgender health center’s HTC services in Metro Manila, Philippines. Moreover, we examined the relationship between gender identity and the non-uptake of HIV testing in the transgender population.

Methods

Study setting

Victoria by Love Yourself Inc. (VLY), the Philippines’ first community-based transgender health center, was established in 2016. Located in Pasay City, Metro Manila, Philippines, the health center receives patients inside and outside said urban capital. This initiative came about in response to the needs of the transgender community, particularly on access to comprehensive and quality transgender healthcare services. It is a one-stop shop that provides holistic care that integrates transgender health and sexual health.

The VLY services include free HTC services, HIV treatment care and support, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) consultation and treatment, PrEP, and PEP. In addition, the center also offers gender-affirming services (GAS), such as gender transitioning counseling, pre-gender affirming surgery assessment and consultation, hormone administration, medically supervised gender-affirming hormone treatment, and even a support group for transgender people. VLY enrolls an average of 21 TM and 8 TW monthly for GAS, whereas around 2 TM and 45 TW visit monthly for their HTC services. HIV testing and treatment services are funded by the Department of Health and Philippine Health Insurance Corporation, the national social health insurance. Additionally, the GAS were initially funded by Stop AIDS Now Fund and LGBT Fund but are now self-sustained by LoveYourself, Inc.

Study design and population

A cross-sectional study of TM and TW clients seeking care at VLY Community Center from March 2017 to December 2019 was conducted using previously collected clinical/medical records data. We determined their issues relating to their sexual health, particularly their non-uptake of HIV testing. All client records of TM and TW who accessed the services of VLY were screened and included in the study using the following criteria: (1) 18-60 years old and (2) those who identify as transgender, and (3) not those who identify as otherwise including but not limited to cisgender, questioning, or genderqueer/non-binary. Those medical records whose patients’ characteristics fit our criteria were included in our study population.

Data collection

Medical charts were reviewed to ascertain information from the eligible study participants, including their age, gender identity, initial year and frequency of clinic visits, smoking and drinking statuses, use of recreational drugs, and non-uptake of offered HTC services. Moreover, data extraction of medical records was carried out following a developed case report form. Encoders were trained and ensured to have sufficient expertise, particularly in handling medical records. To identify inaccuracies and discrepancies during the encoding, a small subsample of at least 10% of the total records was reassessed to validate the data encoded into the developed database.

Exposure and outcome measurements

Gender identity (TW or TM) was the primary exposure in our study. This main exposure was ascertained from the gender identification section of the clients’ medical records. In addition, non-uptake of HIV testing was the outcome of interest among the eligible participants. Non-uptake of HIV testing will be considered if the clients declined or refused HIV testing, while uptake for those who accepted or consented to HIV testing.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for the clients’ demographic profile, gender identity, and non-uptake of HIV testing outcome were calculated. The association between gender identity and the non-uptake of HIV testing of the client (refused or declined HIV testing; consented or accepted HIV testing) was estimated using multivariable generalized linear models (GLMs) with a Poisson distribution, log link function, and a robust variance; a suitable method for cross-sectional data with a common outcome [16,17,18].

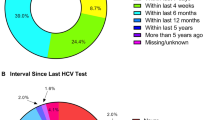

In the Poisson model, the following variables were controlled based on previous literature: age (15 – 24 years old; 25 – 34 years old; 35 years old and above), frequency of clinic visit (1 visit; 2 to 3 visits; 4 visits and above), drinking status (never drinker; ever drinker), recreational drug use (never user; ever user), smoking status (never smoker; ever smoker), and year of initial consult (2017; 2018; 2019). The clients’ characteristics included in the model were chosen a priori as potentially important confounding factors and predictors of HIV testing non-uptake (see Fig. 1 for details) [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

For clients who availed of the HTC services of VLY, descriptive statistics were also calculated and stratified by their HIV test results (reactive vs. non-reactive) to summarize the client’s study characteristics.

Sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding was estimated using an E-value described in the previous report [33]. An adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to report the effect size estimate for the effect of gender identity on non-uptake of HIV testing. STATA 17 software (www.stata.com/stata17/) was used to carry out all statistical analyses.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Following the national guidelines, the study’s research protocol received ethical approval from the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB) (CODE: 2021–105-01). The data gathered and client information were kept confidential and private following the Philippine Data Privacy Act of 2012. Written informed consent form from the participants was not required in our study. The need for informed consent was waived by the UPMREB.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the characteristics of the study population stratified according to gender identity. A total of 525 TW and TM were included in the study. The clients have a mean age (± SD) of 25.8 ± 5.8 years old. Most of them belonged to the 15–24 years old age bracket (46.7%) and 25–34 years old age bracket (46.1%). Approximately 65.6% of the clients were identified as TM, while the rest were TW. The year 2019, as the initial consult, recorded the highest number of clients (55.6%), which is composed mainly of TM (72.9%), while only 9.9% were recorded as an initial consult during the first year (2017) of the VLY. Regarding the non-uptake of HTC services, approximately 82.3% of the clients refused or declined HIV testing and were mostly TM. Conversely, among the 93 patients who consented to or accepted HIV testing, 27 of them were TM (29.0%) (for details, see Table 1).

Table 2 shows the adjusted effect estimate of gender identity on non-uptake of HIV testing. The prevalence of not getting tested for HIV is 48.0% higher among TM clients (aPR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.31 to 1.67; p-value < 0.001) compared to TW clients. Table 2 also shows the E-values for the point estimate and the confidence interval as a result of the sensitivity analysis of the unmeasured confounding. With an observed point estimate prevalence ratio of 1.48, an unmeasured confounder associated with both gender identity and non-uptake of HIV testing by a prevalence ratio of 2.32 each, above and beyond the measured confounder, could explain away the prevalence ratio estimate. But weaker confounding could not. In addition, with an observed lower bound confidence interval prevalence ratio of 1.31, an unmeasured confounder was associated with both gender identity and non-uptake of HIV testing by a prevalence ratio of 1.95 each, above and beyond the measured confounders, could shift the confidence interval to include the null. However, weaker confounding could not.

Clients who consented to or accepted HTC services from the VLY were further described in Table 3 and stratified according to their HIV test results. Regarding gender identity, 96.3% and 89.4% of the TM and TW clients were non-reactive, respectively, which implied that TW had a higher HIV prevalence rate than TM clients (10.6% vs. 3.7%). Moreover, reactive patients were only observed in 2018 & 2019, with approximately one out of ten transgender people testing reactive for HIV. Furthermore, 2019 recorded the most clients who availed the HTC services, 57.0% (53/93). Out of the eight reactive clients, most were on ART treatment 87.5% (7/8); three were already virally suppressed, four were not yet virally suppressed, and one TW was lost to follow up.

Discussion

Several factors may increase the risk of transgender (TG) populations for HIV infection. TW were identified as having more significant risks of acquiring HIV infection than TM. TG populations were also least likely to receive HIV treatments or interventions and other preventative services [2, 34,35,36]. The TG community is also known to experience an increased risk for sexual behaviors, family rejection, stigma, discrimination, and safety concerns [37,38,39]. In addition, numerous individual, social, and interpersonal factors provide an interplay in terms of the experiences the TG community endures [40, 41].

A report on the education and training for health professionals in the Philippines provided information on the adequacy of the current health curricula in terms of the HIV response [42]. Moreover, the Integrated HIV Behavioral and Serologic Surveillance embedded in the Health Sector Plan for HIV and STI 2015 to 2020 of the Philippine Department of Health (DOH), an active sentinel serologic and behavioral surveillance, suggested actions to increase HIV and HIV-related services both for the TG and men-having-sex-with-men (MSM) populations [43, 44]. However, the guidelines for the increase in uptake of HTC services among the TW and TM should be further strengthened because of the existing barriers to testing [45]. Our study aimed to identify gender identity as a factor that enables the TG populations to refuse or decline HIV testing services. Through medical records review, our study showed that most TM did not consent or accept HIV testing services from the VLY, and they are more likely to refuse HIV testing services compared to TG.

Our results conformed with the prevalence report of the US CDC recommended guidelines for HIV and STI, wherein suboptimal trends in HTC services were observed among TG [46]. This finding is congruent with the results that TM did not know their HIV status [47]. However, one study on TG youth showed that TW was significantly less likely to get tested for HIV compared with TM [48]. Contrary to this finding, a recent publication on an extensive survey from the United States consisting of 26,927 TG respondents in 2015 revealed that TW had significantly higher odds of reporting their HIV status than TM [49], which was also seen in our study. In addition, the most common reason for never testing for HIV among TM was a low-risk perception of their sexual activities. Low-risk perception as a significant barrier to HIV testing was also seen in previous studies [50,51,52,53], not only among TG populations. Other reasons for TM or TW not getting their HIV testing also included fear of HIV-related stigma and discrimination [54, 55], insufficient knowledge on HIV/AIDS or poor health literacy [56, 57], and limited availability due to lack of time [58]. Further investigation on why TM and TW in VLY do not know their HIV status because of refusal should be conducted to engage more TM and TW clients in HTC services. Moreover, increasing the willingness for HIV self-testing among TM or TW to ensure one’s safety and confidentiality is an alternative approach that can also be explored [59, 60].

The third year since the launch of VLY in 2017 recorded the highest number of TM and TW clients consenting to HIV testing. As an exclusive health center for the TG community under the supervision of LoveYourself Inc., VLY was initially established to provide HTC [61]. Over the years, through community consultations, partnerships with LGBTQIA + organizations, and TG health capacity building of the community center, VLY officially rolled out their GAS, the first in the Philippines. The one-stop-shop model of integrating sexual health services and TG health could translate to a gradual increase in HIV testing uptake among VLY clients. This strategy further establishes that gender-affirming care services can be an entry point in accessing HIV services.

Similarly, research has suggested that a gender-affirmative integrated care framework complemented by peer navigation effectively addresses the HIV burden experienced by the TG population [62]. Our results also showed that the later years of VLY operations had more TM and TW clients encouraged to avail themselves of the HTC services. In previous reports, this observation was also seen in other centers/clinics [63, 64]. Building trust and rapport between physicians, HTC service providers, and clients are crucial in all central HIV testing practices [64, 65]. The integral approach to establishing trust is, to begin with, simple steps, taking part in clients with small successes and showing dedication and commitment through continuous communication [66]. VLY used this strategy to build trust and rapport with TW and TM clients, which was also seen in previous studies conducted by other HTC providers [67, 68]. The establishment of VLY as a community-based TG health center for TM and TW provides an essential avenue for these populations to avail of HTC services in confidence and without stigma and discrimination.

HIV testing lacking good motivational counseling and linkage to care may not be effective [69]. Our study provided information on reactive TG clients in which almost all were linked to care, particularly HIV treatment through ART. Engagement in HIV care among all vulnerable populations, not only TG clients, is essential in the HIV care continuum. The role of HTC service providers, such as VLY, in the delivery of services and building relationships is characterized by their provision of time and emotional and social support to their clients [70, 71]. However, previous studies documented low ART coverage among TG respondents [72,73,74]. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrated improved access and link to care among HIV-reactive TW and TM clients of VLY, similar to another published study [75].

To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative cross-sectional study conducted in the Philippines that looked at the non-uptake of HIV testing of TM and TW clients. Using a modest sample size of client records, we presented the disparity between TM and TW regarding the non-uptake of HTC services in Metro Manila. Through continuous monitoring and engagement of TM and TW in the community-based TG health center environment, the identified disparity provided an opportunity for the VLY to enhance its services for TM and TW accessing HTC services. Furthermore, by gradually eliminating this gap through the retention of commitment and trust built around with clients and proper dissemination of the availability of HTC services for the TM and TW community, HIV cases in Metro Manila may be reduced.

However, the current study is limited by its secondary data analysis nature, in which participant information was collected through a medical chart review. We acknowledged that missing data in our medical chart documentation may have precluded insightful analysis of other potential predictors. Given its cross-sectional study design, it could not identify the temporal and causal relationships between gender identity and the non-uptake of HIV testing. In addition, our study focused on individual-level exposures rather than societal-level exposures. Additionally, gender identity was the main exposure of our study, wherein it was treated as an attribute that may be relevant to the individual’s health [76]. Hence, other study designs are recommended in future studies to establish causality between the exposure and the outcome of interest, such as randomized control trials.

Moreover, possible selection bias from the sample population could not be ignored because the distribution characteristics of our study population who had access to VLY might not have the same distribution characteristics of those who do not have access to VLY services. Furthermore, our study did not account for the sexual orientation of the study population. TM who have sex with cisgender men and TW are increasingly at risk of HIV. Given the current growing number of national and global programs focused on TW, not TG in general, the exploration of HIV testing uptake in terms of sexual orientation has important implications on TM not perceiving they are actually at risk for the HIV infection. In addition, the potential effect of residual unmeasured confounding factor (i.e., HIV-related social stigma and discrimination) bias could not be ruled out. Furthermore, we only involved TM and TW clients who accessed VLY from 2017 to 2019, which may not be representative of other TM and TW clients in other parts of the Philippines, other races, and other vulnerable populations at-risk for HIV. Further studies are needed to validate our findings across different populations and other community centers.

Conclusion

The role of early HTC services in the reduction of increasing HIV cases is an essential approach in the HIV care spectrum, especially for vulnerable populations such as the TG community. In our study, the non-uptake of HTC service of TM and TW is high. Our study, which demonstrated the refusal rate of HIV testing among TG populations, particularly among TM, presented an opportunity for the HIV program implementers in the Philippines to reach this group to provide the HTC services they need.

Availability of data and materials

The original data are not available for sharing to protect the clients’ confidentiality. An email may be sent to the corresponding author, Dr. Emmanuel S. Baja (esbaja@up.edu.ph), for further inquiries.

Abbreviations

- aPR:

-

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DOH:

-

Department of Health

- GLM:

-

Generalized Linear Models

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HTC:

-

HIV Testing and Counselling

- MSM:

-

Men-having-sex-with-men

- PrEP:

-

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

- PEP:

-

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- STI:

-

Sexually Transmitted Infections

- TG:

-

Transgender

- TM:

-

Trans men

- TW:

-

Trans women

- VLY:

-

Victoria by LoveYourself Inc

References

Feldman J, Romine RS, Bockting WO. HIV risk behaviors in the US transgender population: prevalence and predictors in a large internet sample. J Homosex. 2014;61(11):1558–88.

Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention: HIV among transgender people. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html. Accessed 31 Aug 2021.

Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18734.

Pitasi MA, Oraka E, Clark H, Town M, DiNenno EA. HIV testing among transgender women and men—27 states and Guam, 2014–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(33):883.

Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1820–9.

Shires DA, Jaffee K. Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health Soc Work. 2015;40(2):134–41.

Macapagal K, Bhatia R, Greene GJ. Differences in healthcare access, use, and experiences within a community sample of racially diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning emerging adults. LGBT health. 2016;3(6):434–42.

Maragh-Bass AC, Torain M, Adler R, Schneider E, Ranjit A, Kodadek LM, Shields R, German D, Snyder C, Peterson S. Risks, benefits, and importance of collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in healthcare settings: a multi-method analysis of patient and provider perspectives. LGBT health. 2017;4(2):141–52.

Magno L, Silva LAVd, Veras MA, Pereira-Santos M, Dourado I. Silva LAVd, Veras MA, Pereira-Santos M, Dourado I: Estigma e discriminação relacionados à identidade de gênero e à vulnerabilidade ao HIV/aids entre mulheres transgênero: revisão sistemática. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2019;35(4):e00112718.

Rodríguez-Madera S, Toro-Alfonso J. Gender as an obstacle in HIV/AIDS prevention: Considerations for the development of HIV/AIDS prevention efforts for male-to-female transgenders. IJT. 2005;8(2–3):113–22.

Snow J. Blueprint for the provision of comprehensive care for trans persons and their communities in the Caribbean and other Anglophone countries. 2014.

Quinn VP, Nash R, Hunkeler E, Contreras R, Cromwell L, Becerra-Culqui TA, Getahun D, Giammattei S, Lash TL, Millman A. Cohort profile: Study of Transition, Outcomes and Gender (STRONG) to assess health status of transgender people. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018121.

World Health Organization. Report on the WHO/TDR consultation on promoting implementation/operational research in countries receiving grants from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria: Domaine de Penthes, Geneva, Switzerland 9–10 December 2015. World Health Organization; 2016.

Kenagy GP. Transgender health: Findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health Soc Work. 2005;30(1):19–26.

Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200.

Tamhane AR, Westfall AO, Burkholder GA, Cutter GR. Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: choice comes with consequences. Stat Med. 2016;35(30):5730–5.

McNutt L-A, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–3.

Yaya S, Shibre G, Idriss-Wheeler D, Uthman OA. Women’s empowerment and HIV testing uptake: A meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys from 33 sub-Saharan African countries. IJMA. 2020;9(3):274.

Ha JH, Van Lith LM, Mallalieu EC, Chidassicua J, Pinho MD, Devos P, Wirtz AL. Gendered relationship between HIV stigma and HIV testing among men and women in Mozambique: a cross-sectional study to inform a stigma reduction and male-targeted HIV testing intervention. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e029748.

Lyu H, Zhou Y, Dai W, Zhen S, Huang S, Zhou L, Huang L, Tang W. Solidarity and HIV Testing Willingness During the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Study Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in China. Front Public Health. 2021;9:752965.

Heino E, Ellonen N, Kaltiala R. Transgender identity is associated with bullying involvement among finnish adolescents. Front Psychol. 2021;11:3829.

Ellman TM, Sexton ME, Warshafsky D, Sobieszczyk ME, Morrison EA. A forgotten population: older adults with newly diagnosed HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(10):530–6.

Chen W, Zhou F, Hall BJ, Tucker JD, Latkin C, Renzaho AM, Ling L. Is there a relationship between geographic distance and uptake of HIV testing services? A representative population-based study of Chinese adults in Guangzhou, China. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180801.

Ahmed M, Seid A. Factors associated with premarital HIV testing among married women in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0235830.

Sayal K, Heron J, Golding J, Emond A. Prenatal alcohol exposure and gender differences in childhood mental health problems: a longitudinal population-based study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e426–34.

Dalal S. Lee C-w, Farirai T, Schilsky A, Goldman T, Moore J, Bock NN: Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling: increased uptake in two public community health centers in South Africa and implications for scale-up. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27293.

Vasilenko SA, Evans-Polce RJ, Lanza ST. Age trends in rates of substance use disorders across ages 18–90: Differences by gender and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:260–4.

Pepito VCF, Newton S. Determinants of HIV testing among Filipino women: results from the 2013 Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232620.

Mucha L, Stephenson J, Morandi N, Dirani R. Meta-analysis of disease risk associated with smoking, by gender and intensity of smoking. Gend Med. 2006;3(4):279–91.

Leta TH, Sandøy IF, Fylkesnes K. Factors affecting voluntary HIV counselling and testing among men in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–12.

Diamant AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, Gelberg L. Health behaviors, health status, and access to and use of health care: a population-based study of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1043.

VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–74.

Harper GW, Jadwin-Cakmak LA, Popoff E, Campbell BA, Granderson R, Wesp LM. Interventions AMTNfHA: Transgender and other gender-diverse youth’s progression through the HIV continuum of care: socioecological system barriers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(1):32–43.

Mayer KH, Grinsztejn B, El-Sadr WM. Transgender people and HIV prevention: what we know and what we need to know, a call to action. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(3):S207.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention: HIV among transgender people. Atlanta: CDC; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html. Accessed 31 Aug 2021.

Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):943–51.

Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, Jahan N, Naveed S. Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1184.

Day JK, Perez-Brumer A, Russell ST. Safe schools? Transgender youth’s school experiences and perceptions of school climate. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(8):1731–42.

Apaydin KZ, Fontenot HB, Shtasel D, Dale SK, Borba CP, Lathan CS, Panther L, Mayer KH, Keuroghlian AS. Facilitators of and barriers to HPV vaccination among sexual and gender minority patients at a Boston community health center. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3868–75.

Neumann MS, Finlayson TJ, Pitts NL, Keatley J. Comprehensive HIV prevention for transgender persons. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):207–12.

Tawasil JR, Salvador VD, Juban NR, Chan MB. HIV/AIDS education in health professionals training in the Philippines. 2012.

Asuncion I, Segarra A, Samonte, GMJ, Palaypayon NS, Bermejo MR. The state of the Philippine HIV Epidemic 2016: Facing challenges, forging solutions. Manila: Department of Health. National HIV/AIDS & STI; 2017.

Department of Health Epidemiology Bureau, Philippines: IHBSS fact sheets, Integrative HIV Behavioral and Serological Surveillance. In. Edited by Health Do. Manila; 2018. https://www.aidsdatahub.org/resource/factsheets-2018-integrated-hiv-behavioral-serologic-surveillance-ihbss. Accessed 31 Aug 2021.

Restar AJ, Jin H, Ogunbajo A, Adia A, Surace A, Hernandez L, Cu-Uvin S, Operario D. Differences in HIV risk and healthcare engagement factors in Filipinx transgender women and cisgender men who have sex with men who reported being HIV negative, HIV positive or HIV unknown. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(8):e25582.

Sukhija-Cohen AC, Beymer MR, Engeran-Cordova W, Bolan RK. From control to crisis: the resurgence of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46(2):e8.

Antebi-Gruszka N, Talan AJ, Reisner SL, Rendina HJ. Sociodemographic and behavioural factors associated with testing for HIV and STIs in a US nationwide sample of transgender men who have sex with men. STIs. 2020;96(6):422–7.

Sharma A, Kahle E, Todd K, Peitzmeier S, Stephenson R. Variations in testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections across gender identity among transgender youth. Transgender health. 2019;4(1):46–57.

Olakunde BO, Pharr JR, Adeyinka DA, Conserve DF. Nonuptake of HIV Testing Among Transgender Populations in the United States: Results from the 2015 US Transgender Survey. Transgender Health. 2021.

MacKellar DA, Hou S-I, Whalen CC, Samuelsen K, Sanchez T, Smith A, Denson D, Lansky A, Sullivan P, Group WS. Reasons for not HIV testing, testing intentions, and potential use of an over-the-counter rapid HIV test in an internet sample of men who have sex with men who have never tested for HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(5):419–28.

Febo-Vazquez I, Copen CE, Daugherty J. Main Reasons for Never Testing for HIV Among Women and Men Aged 15–44 in the United States, 2011–2015. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2018;107:1–12.

Bond KT, Frye V, Taylor R, Williams K, Bonner S, Lucy D, Cupid M, Weiss L, Team STS. Koblin BA,: Knowing is not enough: a qualitative report on HIV testing among heterosexual African-American men. AIDS care. 2015;27(2):182–8.

Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, Coleman J, Powell P, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. A routine HIV screening program in a South Carolina community health center in an area of low HIV prevalence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(4):251–8.

Roberts TK, Fantz CR. Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(10–11):983–7.

Jadwin-Cakmak L, Reisner SL, Hughto JM, Salomon L, Martinez M, Popoff E, Rivera BA, Harper GW. HIV prevention and HIV care among transgender and gender diverse youth: design and implementation of a multisite mixed-methods study protocol in the US. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–15.

Burke RC, Sepkowitz KA, Bernstein KT, Karpati AM, Myers JE, Tsoi BW, Begier EM. Why don’t physicians test for HIV? A review of the US literature. AIDS. 2007;21(12):1617–24.

Palumbo R. Discussing the effects of poor health literacy on patients facing HIV: a narrative literature review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(7):417.

White BL, Walsh J, Rayasam S, Pathman DE, Adimora AA, Golin CE. What makes me screen for HIV? Perceived barriers and facilitators to conducting recommended routine HIV testing among primary care physicians in the southeastern United States. (JIAPAC). 2015;14(2):127–35.

Pal K, Ngin C, Tuot S, Chhoun P, Ly C, Chhim S, Luong M-A, Tatomir B, Yi S. Acceptability study on HIV self-testing among transgender women, men who have sex with men, and female entertainment workers in Cambodia: a qualitative analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166129.

Gohil J, Baja ES, Sy TR, Guevara EG, Hemingway C, Medina PMB, Coppens L, Dalmacion GV, Taegtmeyer M. Is the Philippines ready for HIV self-testing? BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–8.

Cousins S. The fastest growing HIV epidemic in the western Pacific. The Lancet HIV. 2018;5(8):e412–3.

Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S235.

Cortes R O03.5 Isean-hivos philippines: strengthening capacities of community-based organisations (CBO) through organisational development (OD) for sustainability of community-led hiv and rights-based interventions Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2017;93:A6-7.

Cousins S. LoveYourself: a safe environment for testing and treatment. The Lancet HIV. 2018;5(8):e415.

Myers T, Worthington C, Haubrich DJ, Ryder K, Calzavara L. HIV testing and counseling: test providers’ experiences of best practices. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(4:Special issue):309–19.

Vangen S, Huxham C. Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. J Appl Behav Sci. 2003;39(1):5–31.

Woods WJ, Erwin K, Lazarus M, Serice H, Grinstead O, Binson D. Building stakeholder partnerships for an on-site HIV testing programme. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(3):249–62.

Prost A, Chopin M, McOwan A, Elam G, Dodds J, Macdonald N, Imrie J. “There is such a thing as asking for trouble”: taking rapid HIV testing to gay venues is fraught with challenges. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(3):185–8.

Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Sabatino J, Lihatsh T, Adler B, Casey S, Rinaldi J, Brand R, McFarland W. Changing sexual behavior among gay male repeat testers for HIV: a randomized, controlled trial of a single-session intervention. J Acquired Immune Defici Syndr. 2002;30(2):177–86.

Broaddus MR, Owczarzak J, Schumann C, Koester KA. Fostering a “feeling of worth” among vulnerable HIV populations: the role of linkage to care specialists. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(10):438–46.

Zamudio-Haas S, Maiorana A, Gomez LG, Myers J. “ No estas solo”: navigation programs support engagement in HIV care for Mexicans and Puerto Ricans living in the continental US. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(2):866–87.

Santos G-M, Wilson EC, Rapues J, Macias O, Packer T, Raymond HF. HIV treatment cascade among transgender women in a San Francisco respondent driven sampling study. STIs. 2014;90(5):430–3.

Sevelius JM, Carrico A, Johnson MO. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):256–64.

Melendez RM, Exner TA, Ehrhardt AA, Dodge B, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus M-J, Lightfoot M, Hong D. Team NIoMHHLP: Health and health care among male-to-female transgender persons who are HIV positive. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1034–7.

Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Retention in care and health outcomes of transgender persons living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(5):774–6.

White E, Armstrong BK, Saracci R. Principles of exposure measurement in epidemiology: collecting, evaluating and improving measures of disease risk factors. OUP Oxford; 2008.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank each individual who had important roles in the production of the manuscript: Dr. Jan Dio Miguel Dela Cruz for his technical experience on transgender health, Hazel Ivy Jeremias for coordinating the team, and the data encoding team, Eldrid Dela Peña and Dax Agcaoili. Data used were collected from Victoria by LoveYourself Inc.

Funding

The study received a research grant from The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria through the Sustainability of HIV Services for Key Populations in Asia (SKPA) Programme, under program grant agreement QMZ-H-AFAO, managed by the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations and implemented in the Philippines by LoveYourself Inc. The funder did not have any role in the study design, implementation, or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All named authors conceptualized the study and developed the protocol. ESB, PCE, AVC, and ZGR led the cleaning and sorting of the data collected. ESB performed the statistical analyses. ZGR and ESB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors helped with the revision of the manuscript. All authors have agreed on the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Following the national guidelines, the study’s research protocol received ethical approval from the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB) (CODE: 2021–105-01). The data gathered and client information were kept confidential and private following the Philippine Data Privacy Act of 2012. The participants’ written informed consent form was not required in our study. The need for informed consent was waived by the UPMREB.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No competing financial interests exist.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Regencia, Z.J.G., Castelo, A.V., Eustaquio, P.C. et al. Non-uptake of HIV testing among trans men and trans women: cross-sectional study of client records from 2017 to 2019 in a community-based transgender health center in Metro Manila, Philippines. BMC Public Health 22, 1755 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14158-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14158-w