Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown period lasted from March to May 2020, resulted in a highly stressful situation yielding different negative health consequences, including the worsening of smoking habit.

Methods

A web-based cross-sectional study on a convenient sample of 1013 Italian ever smokers aged 18 years or more was conducted. Data were derived from surveys compiled by three different groups of people: subjects belonging to Smoking Cessation Services, Healthcare Providers and Nursing Sciences’ students. All institutions were from Northern Italy. The primary outcome self-reported worsening (relapse or increase) or improvement (quit or reduce) of smoking habit during lockdown period. Multiple unconditional (for worsening) and multinomial (for improving) logistic regressions were carried out.

Results

Among 962 participants, 56.0% were ex-smokers. Overall, 13.2% of ex-smokers before lockdown reported relapsing and 32.7% of current smokers increasing cigarette intake. Among current smokers before lockdown, 10.1% quit smoking and 13.5% decreased cigarette intake. Out of 7 selected stressors related to COVID-19, four were significantly related to relapse (OR for the highest vs. the lowest tertile ranging between 2.24 and 3.62): fear of being infected and getting sick; fear of dying due to the virus; anxiety in listening to news of the epidemic; sense of powerlessness in protecting oneself from contagion. In addition to these stressors, even the other 3 stressors were related with increasing cigarette intensity (OR ranging between 1.90 and 4.18): sense of powerlessness in protecting loved ones from contagion; fear of losing loved ones due to virus; fear of infecting other.

Conclusion

The lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with both self-reported relapse or increase smoking habit and also quitting or reduction of it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19 pandemic) is an ongoing global pandemic associated by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS- CoV-2). The outbreak was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020 and a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [2]. To contain and combat the spread of the virus, starting on 11 March 2020, the Italian Government adopted restrictive measures throughout the country: the obligation to wear a surgical mask, the prohibition on leaving home and travel except for urgent reasons and ordered the closure of all facilities in which people gather, such as restaurants, cinemas and museums. Furthermore, smart working and the remote school were activated. This period, called “lockdown”, lasted in its strictest mode until May 18, 2020 [3]. Once the lockdown was over, many measures to contain the pandemic were maintained in the following months; neither during lockdown or later there was restriction of tobacco purchase. In this paper we refer strictly to the lockdown period that characterized the first phase of the pandemic in Italy, as it was the one with the strictest restrictions.

Recent studies have shown that the lockdown confinement and the simultaneous closure of all leisure and socialization activities has important health, economic, environmental and social consequences [4].

Tobacco consumption is the single greatest preventable cause of death in the world today [5] and an important risk factor for disease severity and worse outcomes in COVID-19 [6,7,8,9]. The worsening of life condition due to the changes produced by lockdown suggests that smokers can be likely to increase smoking and that ex-smokers may relapse [10], with further, important health consequences..

Many changes occurred in lifestyle and daily activities such as work routine, sleeping habits, physical inactivity and nutritional habits [11, 12]. These aspects, in turn, may have induced in people a change in their smoking behavior [13].

Regarding psychiatric pathologies, the current evidence suggests that a psychiatric epidemic is occurring parallel to the COVID-19 pandemic, which is increasingly worrying to the global healthcare community [14]. An increase in several psychiatric disorders including anxiety, sleep disorders and panic has been detected to a larger extent in people who already had a previous vulnerability to psychiatric pathologies [15, 16]. Since nicotine produces acute anxiolytic effects [17] smokers who experience elevated anxiety symptoms are more likely to use smoking as a means of regulating their mood [18].

Only a few studies have thoroughly investigated the change in smokers’ and ex-smokers’ behaviors associated to lockdown and the influencing variables. The results reported to date are rather ambivalent: Caponnetto et al. [19] found a slight decrease in cigarette consumption and a slight increase in e-cigarette use, whereas Bommele et al. examined the role of stress in influencing the amount of cigarettes smoked and found that moderate and high levels of stress can induce both a reduction and an increase in smoking [20]. Stress, however, is certainly an important factor to consider, given its ability to induce an increase in smoking [21].

Starting from this background we wanted to investigate if ever smokers reported getting worse in smoking habit (i.e., relapse for ex-smokers before lockdown or increase in the number of cigarettes per day for current smokers before lockdown), or having improved it (i.e., smoking cessation or reduction in the number of cigarettes per day for current smokers before lockdown). Moreover, we aimed to exploratorily evaluate the relationship between selected specific stressors and changes in smoking behavior due to COVID-19. We conducted this analysis on three different Northern Italy populations, assuming that they could have been particularly hit by the confinement measures: heavy ever smokers attending Smoking Centers Services (SCSs), Healthcare Providers (HPs), and Nursing Sciences’ students.

Material and methods

We conducted a web-based cross-sectional study on a sample of Italian ever smokers aged 18 years or more to observe the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on smoking habits. The web-based survey was launched by e-mail on May 15th 2020, and remained available for 1 month.

Study population and sampling procedure

Data were derived from a sample of 1013 Italian adults aged 18-80 years from northern Italy. Study participants were a convenience sample of ever smokers recruited among three different groups of the population: i) subjects referred to Smoking Cessation Services (SCSs), ii) Healthcare Providers (HPs), and iii) Nursing Sciences’ students. The SCSs included were the National Cancer Institute (Milan, Italy), the Alcohol and New Addictions Unit of the Major Hospital of Milan, (ASST Brianza, Vimercate, Italy) and the Unit of Addiction Medicine (Integrated University Hospital of Verona, Verona, Italy). The HPs involved belonged to the National Cancer Institute (Milan, Italy) and to the Integrated University Hospital of Verona. Nursing Sciences’ students were recruited from the University of Verona.

To recruit the sample, participants have been contacted by email: 943 email of the subjects referred to Smoking Cessation Services (SCSs), 817 email of Healthcare Providers (HPs), and 293 email of Nursing Sciences’ students. The availability of the email addresses of these last two groups was there because of their participation in several past years in educational events on smoking cessation organized by the anti-smoking services of Milan and Verona. Therefore subjects from HPs and Students were both ever smokers and never-smokers. Only ever smokers were asked to answer.

An online survey, composed of 26 multiple-choice questions and eight open questions, for a total of 34 questions, was created on Survey Monkey. The link to the online questionnaire was sent by e-mail to all current and ex-smokers who had attended an SCS before the lockdown, and to HPs and students of the hospitals involved in the study.

The survey targeted ever-smokers (respondents who reported smoking ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime) [22]; the link to the questionnaire was sent to 2053 subjects via mail. They were then asked whether they were current smokers (respondents who reported smoking ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime and has smoked in the last 28 days) or ex-smokers (respondents who reported smoking greater than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but has not smoked in the last 28 days) on the date of completion of questionnaire. The time needed to complete it was approximately 15 min, and each subject was able to fill in the online survey only once. Participation in the survey was voluntary, anonymous and without remuneration. Participants expressed their consent to participate in the study by completing the corresponding field in the online questionnaire.

Independent variables

The survey included questions regarding socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age, marital status, children’s presence, educational qualification and employment status). Instead of educational qualification, a specific question about current profession was asked to the HPs.

The survey comprised a section that included a combination of 21 stressors potentially associated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the first lockdown in Italy. We divided the 21 stressors into four groups considering their common characteristics (Table 1). To select the stressors, we referred to the work of Taylor [23], whose research and clinical observations suggested that during times of pandemics many people experience fear and anxiety referring to the following areas of discomfort: fear of becoming infected, fear of coming into contact with potentially contaminated objects or surfaces, fear of strangers who may be carrying infections (e.g. related xenophobia), fear of the socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic (e.g. job loss), compulsive control, and seeking reassurance about possible pandemic-related threats and symptoms of traumatic stress about the pandemic (e.g., nightmares and intrusive thoughts). We qualitatively select the areas of most interest, excluding those that were studied in other parts of the questionnaire.

Table 1 The impact of lockdown on mood was evaluated through a question based on a seven point Likert scale (ranging from 1 “my mood is much improved” to 7, “my mood is much worse”) that explored the difference between the period before and during lockdown. Sleep quality was evaluated by a four choice question: very good, good enough, bad enough, and very bad.

The psychological aspects and the emotional impact related to lockdown were investigated using two Italian validated scales: the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was used to investigate respondents’ quality of life [24,25,26,27] and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Y-1 (S.T.A.I. Y-1) to investigate state anxiety during lockdown [28, 29].

Main outcome variables

The survey had a section dedicated to smoking behavior, divided in two subsections: one for ex-smokers and one for current smokers. Ex-smokers were asked to report the date they quit to further divide them into ex-smokers for more than 12 months and ex-smokers for less than 12 months. The section for ex-smokers included questions about the age at starting smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked per day and cravings related to the lockdown. The section for current smokers included questions about age when starting smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked per day before lockdown, the number of cigarettes smoked per day during lockdown and the idea of quitting smoking related to the beginning of lockdown. Moreover, current smokers were asked whether they were ex-smokers before lockdown and relapsed during the lockdown and, in case of relapse, about their smoking cessation’ year and month.

Through self-reporting, we defined worsening smoking habit during lockdown if i) individuals relapsing in smoking vs. those not relapsing among ex-smokers before lockdown, ii) individuals increasing vs. those not increasing the number of cigarettes per day smoked among current smokers before lockdown. We defined improving smoking habit during lockdown if: i) individuals reported have quitted smoking and ii) individuals reported to have kept smoking during lockdown, but decreased the total number of cigarettes per day smoked, both compared with those who did not improve (not quit and not decrease the number of cigarettes per day) their smoking habit among smokers before lockdown.

Statistical analysis

A power calculation was not a priori performed. By protocol we hypothesized to obtain the filled in questionnaire for 400 of the 800 invited subjects from the SCS. No hypothesis was assumed for the other centers. A post-hoc power calculation was performed with 962 individuals, assuming alpha = 0.05 and the prevalence of people worsening smoking habit of 30%, our data have sufficient statistical power (> 0.80) to obtain a statistically significant odds ratio (OR) of 1.50 in a dichotomous variable with equally distributed categories.

We considered descriptive statistics including relative frequency (%) for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression models after adjustment for sex, age group and group of participants (SCSs, HPs and students) were used to derive odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for worsening smoking habits during lockdown. Multinomial logistic regression models after adjustment for the same covariates were used to derive ORs for improving smoking habits during lockdown. The Statistical significance level (alpha) was set to 0.05. After checking the linearity assumption for age using Box-Tidwell test for all the models, we considered age in categories.

All statistical analyses were performed using the software SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Survey respondents

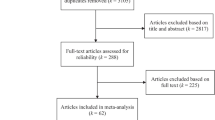

Of 2053 subjects that received the link to the questionnaire, 1013 responded (Fig. 1). Fifty-one were excluded from data analysis because they did not report their smoking status before lockdown. Thus, a total of 962 participants were included in this study. Response rate was respectively 62% for SCSs, 42% for HPs and 31% for Students.

Sociodemographic variables and smoking habits before and during the COVID-19 lockdown

Sociodemographic characteristics and smoking habits before and during the COVID-19 lockdown are presented in Table 2. The total sample of 962 ever smokers (56.0% ex-smokers and 44.0% smokers before lockdown) had a mean age of 48.6 years (SD: 13.8); 58.9% were women. The majority of respondents belonged to the SCS group (59.5%).

Relapse in ex-smokers and worsening of current smokers before lockdown

Table 3 shows the distribution of ex-smokers and current smokers before lockdown according to a self-reported worsening of their smoking habit. We found that 13.2% of the 539 ex-smokers before lockdown stated to have relapsed during lockdown and that 32.7% of the 416 current smokers reported to have increased the number of cigarettes per day during the lockdown (mean increase, 6.2 cigarettes per day; SD, 4.5). Relapse was less frequently reported with increasing pack-years (p for trend = 0.033). Relapses were more frequently reported among widowed (compared married/cohabitants; OR = 4.20; 95% CI, 1.15-15.3) and ex-smokers who quit after 2018 (OR = 7.22; 95% CI: 3.53-14.8). No relationship between sex, age and group of participants, and relapse was observed.

Among the current smokers before lockdown (Table 3), a self-reported increased number of cigarettes per day during lockdown was associated with being female (compared to male, OR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.00-2.44) and increasing pack-years (p for trend < 0.001). No statistically significant relationship was found between age, marital status and group of participants.

Table 4 shows the distribution of ex-smokers and current smokers before lockdown according to a self-reported worsening of their smoking habit due to the COVID-19 lockdown by psychological indicators. We found that relapse was more frequently reported with decreasing quality of life (p for trend < 0.001), decreasing sleep quality (p for trend = 0.033) and high levels of anxiety during lockdown (p for trend < 0.001). An increase in smoking intensity was more frequently observed with worsening quality of life (p for trend < 0.001), worsening sleep quality (p for trend < 0.001) and anxiety levels (p for trend < 0.001) (Table 4).

Improvement in smoking habit in current smokers before lockdown

Among the 416 current smokers before lockdown, 23.6% self-reported to have improved their smoking habit; in particular, 10.1% stated to have quit smoking and 13.5% to have decreased the number of cigarettes per day during lockdown (Table 5).

Quitting smoking decreased with increasing age (p for trend = 0.005) and was less frequent among the HPs compared to the SCS participants (OR = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.12-0.66).

A decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked per day was less frequently observed with increasing age (p for trend = 0.008) and pack-years (p for trend < 0.001) (Table 5) and with intermediate anxiety levels (OR = 2.27; 95% CI, 1.04-4.95) (Supplementary Table S1).

COVID-19 related stressors

Focusing on stressors (Table 6), we analyzed their relationship with a change in smoking habit.

Regarding relapses, in the first category, stressors related to COVID-19, we found four out of seven significant values with an OR range between 2.24 and 3.62; in the second category, stressors due to isolation, we found four out of five significant values with an OR range between 1.86 and 3.12; in the third category, social issues resulting from lockdown, we found two out of four significant values with an OR range between 2.29 and 2.39; in the fourth category, professional and school issues, we found two out of five significant values with an OR range between 1.72 and 2.00.

Regarding the self-reported increase in the number of cigarettes per day, in the first category, stressors related to COVID-19, we found that all stressors were significant with an OR range between 1.90 and 4.18; in the second category, stressors due to isolation, we found two out of five significant values with an OR range between 1.73 and 1.98; in the third category, social issues resulting from lockdown, we found two out of four significant values with an OR range between 1.86 and 3.16; in the fourth category, professional and school issues, no stressors were found to be significant.

Desire to quit smoking in current smokers during lockdown

The desire to quit smoking was investigated among 441 current smokers during lockdown (Supplementary Table S2). Overall, in 28.6% of the current smokers the desire of quitting was less present, in 36.2% was not modified, and in 35.2% of respondents it was more present during lockdown compared to before lockdown. Students were the subgroup of participants who reported higher percentages of the desire to quit smoking (50.0%) compared to SCSs (34.9%) and HPs (30.8%).

The desire to quit smoking appears to be inversely related to an increase number of cigarettes smoked per day. Subjects smoked less during lockdown, thus they improving their smoking habit, and wanted to quit smoking more (51.8%) compared to those increasing the number of cigarettes per day (44.8%).

Discussion

Overall, our data suggest that the COVID-19 lockdown resulted in both: a self-reported worsening (13.2% relapsed and 32.7% increased smoking, on average, by six cigarettes per day) and improvement of smoking status (10.1% quit smoking and 13.5% decreased the number of cigarettes per day). These results seem to be in line with existing literature: to date, the research evidence is ambiguous in explaining the effect of COVID-19 lockdown on smokers and looking like it can induce both a worsening and an improvement in smoking habits [20, 30] . To further contribute to this research, we aimed to examine how different factors could be associated to these changes in smoking habits.

To deal with this topic, we used a cross-sectional study design consistent with our research goals, even if it presents different limitations. Due to this design, we could not infer causality from our data because our survey was administered at one time point; thus, we do not have an indication about the causal sequence of events. Moreover, a sample size was not calculated a priori and the enrollment methodology used (convenience sample) did not allow us to obtain a representative sample of ever smokers and to derive conclusions scalable to the general Italian population. For specific subgroups, such as widowed, the estimates were based on few subjects only. These findings should therefore be confirmed by larger studies. Moreover, we did not investigate stressors as mediators between lockdown and changes in smoking habit through a mediation analysis. Considering these limitations, this analysis enabled us to investigate how different and potentially vulnerable subgroups of the Italian population reacted to the COVID-19 lockdown. Our results suggest early hypotheses for future longitudinal research, whose purpose will be to increase the evidence of the associations between exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic and smoking habit.

We considered three different smokers’ groups: SCS’ patients, HP and nursing students. We found no differences between the three groups except for smoking improvement: HPs quit smoking less than the others. This result was confirmed in other studies: Italian doctors are not so likely to quit smoking [31] and healthcare providers exposed to SARS-CoV-2-infected patients presented a higher risk of showing symptoms of anxiety, depression, sleep disorders and psychological distress [32, 33] and an increased difficulty in reducing or quitting smoking [34] in this pandemic period.

Starting from our data, smoking history and some specific consequences of lockdown seem to play an important role.

Regarding smoking history, the time of quitting was found to be the factor that induced more vulnerability in relapse: subjects who quit smoking for a year or less relapsed more than others. This evidence is supported by experimental research, i.e. event-related potential’ (ERP) studies: ex-smokers of an average of 1.4 years display the same (low) level of processing bias as never-smokers; thus, they are less vulnerable to a reaction to smoking related stimuli [35]. From clinical research we know that ex-smokers remain at risk of relapse throughout their lives without the extraordinary distress caused by the pandemic: half of new ex-smokers relapses within the first year of cessation [30], but those remain smoke-free for at least 12 months have a 35% chance of relapse throughout the course of their lives [36, 37]. Treatment of chronic tobacco addiction after cessation in ex-smokers has been extensively investigated and remains a challenge: which is one of reasons why in SCS long-term counseling is always recommended for at least 6 months and preferably for 12 months, or even longer during this period. This support could now be provided in different forms to the general population (i.e. online or telephone counseling, automatic messages, educational videos) and should contain specific information about the importance of maintaining smoking cessation status during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Still on smoking history, we found an apparent contradiction: more frequent smokers were more likely to increase the number of cigarettes smoked per day during the lockdown, but, as the pack-years increased, relapses among ex-smokers decreased. It is known that smokers with a smoking history greater than 20 pack-years present significantly higher scores of physical dependence, pleasure of smoking and automatism [38]; therefore they are more inclined to worse their smoking behavior than those who smoke less. However, higher resistance to relapse in former heavy smokers has also been reported, albeit less frequently [39]. One possible explanation is that ex-smokers with a history of heavy addiction internalized the importance (and the difficulty) of quitting and the damage they inflict on themselves when relapsing. In any case, these data should encourage smokers and smoking cessation operators to believe in the utility of promoting smoking cessation even in the most addicted smokers.

Regarding protective factors, in our sample the duration of addiction is likely to play a role: younger ex-smokers (ex-smokers under 40 and students) suffered less from the increased desire to smoke; at the same time among students, the desire to quit was present to a greater extent. These data suggest that young people are more susceptible to attempts to quit and are less prone to relapse; studies from tobacco industries [40], conducted for the opposite target, have underlined that young people have both the highest propensity to quit and receive the most potential benefits from smoking cessation. Furthermore, the lockdown not only negatively influenced smokers and ex-smokers: Jackson found that lockdown was not associated with a significant change in smoking prevalence, but with increases in cessation and quit attempts by smokers [30]. Our data show that smokers under 55 years of age with medium levels of anxiety during lockdown and fear of becoming sick self-reported to have improved their health by completely quitting or reducing cigarettes uses. This result is in line with studies highlighting the functionality of average anxiety and fear, as they help one to prepare for action and to functionally adapt to the living environment [41]. The COVID-19 pandemic, associated with functional distress rates in our populations can therefore represent a circumstance leading individuals to positive behavior change; targeted communication and informative and antismoking programs can produce a useful “teachable moment” [42]. In line with other studies that underline a worsening in smoking habit and wellbeing during lockdown [43,44,45,46], our data suggest that the COVID-19 lockdown in this populations has also been a source of high distress, high levels of anxiety and reduced perception of quality of life. The psychological stress, a nonspecific organic response to stressful situations accompanied by physical and psychological symptoms, [47] has an important role in inducing unsanitary living conditions, such as tobacco use [48]. In fact, it is known that a relation between smoking and stress exist [21]. A novel human laboratory model indicated that smokers were less able to gave up cigarettes, smoked more intensely and detected greater gratification and reward from smoking afterward a stress induction, relative to the neutral condition [49]. Hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity, physiologic reactivity, tobacco craving and negative emotion increased significantly due to stress induction [49].

Carreras’ research in Italian smokers [46] showed that the worsening in smoking habit was associated with an increase in mental distress during the COVID-19 lockdown.

In our study, the stressors related to lockdown that mostly involved an increase in cigarette consumption were those related to COVID-19: the fear of being infected and infecting others, and the fear of dying from it. A significant relationship was previously identified between fear and stress from COVID-19, anxiety and depression, as well as significant effects from being sick and having friends or family members who are infected or have died [50]. In addition, among tobacco smokers, there is a perception of an increased vulnerability of their health [51]; this increases the psychological impact of the fear of COVID 19 and, in a vicious circle, favors an increase in smoking, even if smoking exposes the person to an even greater risk from COVID-19.

Among the specific stressors related to COVID-19, the anxiety associated by listening to the news regarding the pandemic has, in our sample, the greatest effect on smoking relapse. The news regarding the fast and wide spread of both accurate and inaccurate information about the COVID-19 pandemic, called an “infodemic”, is considered by the WHO as a problem to manage [52] because of the physical and mental health risks poses for people. Both the continuous exposure to news related to the pandemic and how the news is provided, aimed at increasing the emotional impact, have produced psychological damage, and favored relapses in the context of smoking. It is already known that during the COVID-19 outbreak, news media played an important role in triggering anxiety in people who regularly read relevant news [53, 54]. The WHO [55] guidelines for coping with stress during the COVID-19 outbreak suggest limiting worry and agitation by lessening the time spent watching or listening to media spreading news perceived as upsetting.

In this completely new and upsetting situation social media collaborated to worsen people’s state of mind, but, now more than ever, technology and social media are being used on a massive scale to keep people safe, informed, productive and connected [52]. Social network and video call systems constituted a real lifeline for people isolated because of illness or physical distancing requirement. In all social networks, pages and group dedicated to self-help support of ex-smokers were created, and professional anti-smoking, and relapse prevention interventions have been tested. The effectiveness of these tools in preventing relapses is not yet fully known [56], but the helpfulness of social networks’ support has been demonstrated by the number of page visits and interactions [57].

The relationship between smoking and psychiatric symptoms is a studied issue [58, 59]. Anxiety is one of the psychiatric disorders most related to smoking and increased susceptibility to stress: many smokers wrongly believe that smoking helps to relieve stress, so they consider smoking as an instrument to manage high stress’ levels [60]. However, a systematic review concluded that it was not possible to identify a unique model to consider the relationship between anxiety and smoking and that a bidirectional relationship between the two is possible [61]. Smoking and anxiety have a bidirectional relationship as they influence each other. So, it is important to spread that smoking is also a cause of increased anxiety and that quitting can reduce it with a consequent wellness improvement. Simultaneously, promoting alternative stress and anxiety management strategies may be useful in preventing relapses and an increase in the number of cigarettes.

Further studies are needed to better define the role of the various factors present in this complex situation, but it is possible to state that it would be useful for governments to pay attention to the physical and psychological health consequences deriving from the restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic by implementing information campaigns on stress management and telephone and online support channels because this has an important impact on the quality of life, lifestyle and health.

Conclusion

The lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic created a highly stressful situation for ever-smokers and relapse or increasing in the number of cigarettes smoked have been associated with it. Despite this, smoking cessation still occurred in this period, particularly in the younger participants of our sample.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available because we prefer that these data are not made public to avoid any type of exploitation by external companies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Novel Coronavirus—China, https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020. Accesed 11 Mar 2020.

Gazzetta Ufficiale. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri 9 Marzo 2020, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg. Retrieved 2020 May 7.

Matias T, Dominski FH, Marks DF. Human needs in COVID-19 isolation. J Health Psychol. 2020, 2020:1359105320925149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320925149 [Epub ahead of print].

WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43818.

Vardavas CI, Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of the evidence. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:20. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/119324.

Cattaruzza MS, Zagà V, Gallus S, D'Argenio P, Gorini G. Tobacco smoking and COVID-19 pandemic: old and new issues. A summary of the evidence from the scientific literature. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(2):106–12. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i2.9698.

Patanavanich R, Glantz SA. Smoking is associated with COVID-19 progression: a meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(9):1653–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa082 PMID: 32399563; PMCID: PMC7239135.

Gallus S, Lugo A, Gorini G. No double-edged sword and no doubt about the relation between smoking and COVID-19 severity. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;77:33–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.06.014 Epub 2020 Jun 13. PMID: 32564904; PMCID: PMC7293499.

Patwardhan P. COVID-19: risk of increase in smoking rates among England’s 6 million smokers and relapse among England’s 11 million ex-smokers. BJGP Open. 2020;4(2):bjgpopen20X101067. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101067 PMID: 32265183; PMCID: PMC7330228.

Ping W, Zheng J, Niu X, Guo C, Zhang J, Yang H, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234850. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234850 PMID: 32555642; PMCID: PMC7302485.

Pišot S, Milovanović I, Šimunič B, Gentile A, Bosnar K, Prot F, et al. Maintaining everyday life praxis in the time of COVID-19 pandemic measures (ELP-COVID-19 survey). Eur J Pub Health. 2020;30(6):1181–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa157 PMID: 32750114; PMCID: PMC7454518.

Viana DA, Andrade FCD, Martins LC, Rodrigues LR, Dos Santos Tavares DM. Differences in quality of life among older adults in Brazil according to smoking status and nicotine dependence. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1072-y.

Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, Faizah F, Mazumder H, Zou L, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.24457.1 PMID: 33093946; PMCID: PMC7549174.

Banerjee D. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on elderly mental health. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5320. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32364283; PMCID: PMC7267435.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729 PMID: 32155789; PMCID: PMC7084952.

Morissette SB, Tull MT, Gulliver SB, Kamholz BW, Zimering RT. Anxiety, anxiety disorders, tobacco use, and nicotine: a critical review of interrelationships. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(2):245–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.245 PMID: 17338599.

Morrell H, Cohen L. Cigarette smoking, anxiety, and depression. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 28:4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-005-9011-8.

Caponnetto P, Inguscio L, Saitta C, Maglia M, Benfatto F, Polosa R. Smoking behavior and psychological dynamics during COVID-19 social distancing and stay-at-home policies: a survey. Health Psychol Res. 2020;8(1):9124. https://doi.org/10.4081/hpr.2020.9124.

Bommele J, Hopman P, Walters BH, Geboers C, Croes E, Fong GT, et al. The double-edged relationship between COVID-19 stress and smoking: implications for smoking cessation. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:63. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/125580 PMID: 32733178; PMCID: PMC7386200.

Siegel A, Korbman M, Erblich J. Direct and indirect effects of psychological distress on stress-induced smoking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(6):930–7. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.78.930.

https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/tobacco-control/tobacco-control-information-practitioners/definitions-smoking-status. Accessed 15 June 2015.

Taylor S. The psychology of pandemics: preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2019.

Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. London: Oxford University Press; 1972.

Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988.

Politi PL, Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Reliability, validity and factor structure of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire among young males in Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(6):432–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01620.x.

Giorgi G, Leon-Perez JM, Castiello D’Antonio A, Fiz Perez FJ, Arcangeli G, et al. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) in a sample of Italian workers: mental health at individual and organizational level. World J Med Sci. 2014;11:47–56. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wjms.2014.11.1.83295.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Pedrabissi L, Santinello M. STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Forma Y Manuale. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali; 1989.

Jackson SE, Garnett C, Shahab L, Oldham M, Brown J. Association of the COVID-19 lockdown with smoking, drinking and attempts to quit in England: an analysis of 2019-20 data. Addiction. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15295. Epub ahead of print.

Lina M, Mazza R, Borreani C, Brunelli C, Bianchi E, Munarini E, et al. Hospital doctors’ smoking behavior and attitude towards smoking cessation interventions for patients: a survey in an Italian Comprehensive Cancer Centre. Tumori. 2016;2016(3):244–51. https://doi.org/10.5301/tj.5000501.

De Sio S, Buomprisco G, La Torre G, Lapteva E, Perri R, Greco E, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on doctors' well-being: results of a web survey during the lockdown in Italy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(14):7869–79. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202007_22292.

Wańkowicz P, Szylińska A, Rotter I. Assessment of mental health factors among health professionals depending on their contact with COVID-19 patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165849.

Du J, Mayer G, Hummel S, Oetjen N, Gronewold N, Zafar A, et al. Mental health burden in different professions during the final stage of the COVID-19 lockdown in China: cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e24240. https://doi.org/10.2196/24240.

Littel M, Franken IH. The effects of prolonged abstinence on the processing of smoking cues: an ERP study among smokers, ex-smokers and never-smokers. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(8):873–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881107078494.

European Network for Smoking and Tobacco. Linee guida per il trattamento della dipendenza da tabacco. 2018. http://elearning-ensp.eu/assets/guides/guidelines_2018_italian.pdf. Retrieved 08/01/2021.

West R, Shiffman S. Smoking cessation fast facts: indispensable guides to clinical practice. Oxford: Health Press Limited; 2004.

Rocha SAV, Hoepers ATC, Fröde TS, Steidle LJM, Pizzichini E, Pizzichini MMM. Prevalence of smoking and reasons for continuing to smoke: a population-based study. J Bras Pneumol. 2019;45(4):e20170080. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-3713/e20170080.

Nakamura M, Oshima A, Ohkura M, Arteaga C, Suwa K. Predictors of lapse and relapse to smoking in successful quitters in a varenicline post hoc analysis in Japanese smokers. Clin Ther. 2014;36(6):918–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.03.013. Epub 2014 May 5.

Ling PM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry research on smoking cessation. Recapturing young adults and other recent quitters. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 1):419–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30358.x.

Yerkes RM, Dodson JD. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol. 1908;18:459–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.920180503.

Flocke SA, Clark E, Antognoli E, Mason MJ, Lawson PJ, Smith S, et al. Teachable moments for health behavior change and intermediate patient outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(1):43–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.014. Epub 2014 May 1.

Pieh C, O’Rourke T, Budimir S, Probst T. Relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0238906. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238906.

Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114065.

Tzu-Hsuan Chen D. The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in smoking behavior: Evidence from a nationwide survey in the UK. Tob Prev Cessat. 2020;6:59. https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/126976.

Carreras G, Lugo A, Stival C, Amerio A, Odone A, Pacifici R, et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on smoking consumption in a large representative sample of Italian adults. Tob Control. 2021:tobaccocontrol–2020–056440. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056440. Epub ahead of print.

Bezerra CM, Assis SG, Constantino P. Psychological distress and work stress in correctional officers: a literature review. Cien Saude Colet. 2016;21(7):2135–46. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015217.00502016.

Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Sliwa K, Zubaid M, Almahmeed WA, et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):953–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17019-0.

McKee SA, Sinha R, Weinberger AH, Sofuoglu M, Harrison EL, Lavery M, et al. Stress decreases the ability to resist smoking and potentiates smoking intensity and reward. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England). 2011;25(4):490–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881110376694.

Koçak O, Koçak ÖE, Younis MZ. The psychological consequences of COVID-19 fear and the moderator effects of individuals’ underlying illness and witnessing infected friends and family. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041836.

Kowitt SD, Cornacchione Ross J, Jarman KL, Kistler CE, Lazard AJ, Ranney LM, et al. Tobacco quit intentions and behaviors among cigar smokers in the United States in response to COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155368.

World Health Organization (WHO). Managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Promoting healthy behaviours and mitigating the harm from misinformation and disinformation. 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation. Retrieved 2021 January 5.

Hamidein Z, Hatami J, Rezapour T. How people emotionally respond to the news on COVID-19: an online survey. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2020;11(2):171–8. https://doi.org/10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.809.2. Epub 2020 Apr 20.

Ahmad AR, Murad HR. The impact of social media on panic during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan: online questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e19556. https://doi.org/10.2196/19556.

World Health Organization (WHO). Coping with stress during the 2019-nCoV outbreak. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/coping-with-stress.pdf?sfvrsn=9845bc3a_2. Retrieved 2021 January 5.

Thrul J, Tormohlen KN, Meacham MC. Social media for tobacco smoking cessation intervention: a review of the literature. Curr Addict Rep. 2019;6(2):126–38. Epub 2019 Apr 26.

Onezi HA, Khalifa M, El-Metwally A, Househ M. The impact of social media-based support groups on smoking relapse prevention in Saudi Arabia. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018;159:135–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.03.005. Epub 2018 Mar 9.

Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:440–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912.

Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O’Loughlin J, Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-356.

Fidler JA, West R. Self-perceived smoking motives and their correlates in a general population sample. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(10):1182–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp120. Epub 2009 Jul 28.

Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafò MR. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw140.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM: conception and design of the study; methodology; writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript; supervision. RG: conception and design of the study; methodology; writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. SG: conception and design of the study; statistical analyses; methodology; data curation; software. AL: conception and design of the study; statistical analyses; methodology; data curation; software. CV: conception and design of the study; data acquisition. RB, FL, BT, GMA: data acquisition. CS: statistical analyses; methodology; data curation; software. All authors critically reviewed the content and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori di Milano (approval number INT 105-20). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Distribution of the 416* current smokers before lockdown (multinomial logistic regression analysis). Table S2. Distribution of the 441 current smokers* during lockdown according to their desire to quit smoking.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Munarini, E., Stival, C., Boffi, R. et al. Factors associated with a change in smoking habit during the first COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian cross-sectional study among ever-smokers. BMC Public Health 22, 1046 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13404-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13404-5