Abstract

Background

Undernutrition puts children in a physical and cognitive disadvantage. Animal source foods (ASFs) are important components of nutritious diets and play a significant role in increasing dietary diversity and minimizing the risk of undernutrition among children. Ethiopia still suffers from child undernutrition and there’s no adequate information regarding consumption of ASFs. The objective of this study was to determine the magnitude and determinanats of ASF consumption among children 6–23 months of age.

Methodology

A total weighted sample of 2861 children drawn from the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey was analyzed using “SVY” command of STATA 14.0. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine the independent determinants of ASF consumption. The strength of the association was measured by odds ratio and 95% confidence interval and p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Nearly half (46.5%) of the children reported consuming any type of ASF. Religion, child age, number of household assets, number of livestock owned by a household, and ownership of land usable for agriculture were significant determinants of the outcome variable. The odds of ASF consumption were six times, twice, and 70% lower in orthodox children compared to other (catholic, traditional, or others), muslim, and protestant children, respectively. Household ownership of assets and livestock led to an increase in consumption of ASF by 19 and 2%, respectively. Children aged 18–23 months were more likely to consume ASF as compared to the younger age group (6–8 months old children). In the contrary, children from households that own land usable for agriculture were 33% less likely to consume ASFs as compared to those from households that do not own.

Conclusions

In Ethiopia, only nearly half of children aged 6–23 months consume any type of ASF. The findings of this study imply that ASF consumption can be increased through integrated actions that involve community and religious leaders and programs focused on empowering households’ capability of owning other socioeconomic entities including assets and livestock. This study also may contribute to the growing body of research works on the importance of ASF provision in preventing child undernutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Child undernutrition, the damaging result of poor nutrition during the first 1000 days of life, puts children in a physical and cognitive disadvantage [1]. Globally, 149 million under 5 children were estimated to be stunted in 2018 [2]. Undernutrition has been known as an underlying cause for reduced cognitive skills, lower school performance, morbidities, poverty, and nearly half of under-five deaths [3]. Standard infant and young child feeding recommendations have been established as ways to improve nutrition outcomes [4]. At 6 months of age, infants should start complementary feeding without stopping to breastfeed. A highly diversified complementary diet increases energy and nutrients intakes, and hence improves the nutritional status of children [5].

Animal-source foods (ASFs) are important components of nutritious diets and play a significant role in minimizing the risk of undernutrition among vulnerable groups [6]. Consumption of such foods by older infants and young children has been found to increase dietary diversity. High Dietary diversity has been shown to strongly contribute to improved nutritional results in children [7]. According to a systematic review of studies done in food-insecure areas, consumption or provision of additional complementary foods has been effective at reducing undernutrition. However, to get better results, this should be combined with education [8, 9]. Dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese), flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry and organ meats), and eggs are the three ASFs that make-up the eight food groups illustrated by the World health organization (WHO) to determine optimal dietary diversity [10].

Animal source foods (ASFs) are energy-dense foods that contain the highest quality proteins yielding all the essential amino acids in amounts and forms human beings require. They are also efficient sources of bioavailable micronutrients including iron, zinc, vitamin A, vitamin B12, riboflavin, and calcium, which are of utmost concern globally when addressing food insecurity [11, 12]. Besides, they contain lower levels of anti-nutritional factors compared to plant source foods [13].

Although the stunting reduction rate Ethiopia has achieved is outstanding, the problem remains a major challenge, with approximately two out of five under 5 children are stunted (short for their age). Moreover, micronutrient deficiencies, especially of iron, vitamin A, iodine and zinc, are common among children. Annually, such problems of undernutrition cost the country 4.7 billion USD or 16% of its Gross domestic product (GDP). To tackle such problems of undernutrition, Ethiopia developed and applied different approaches like the National Nutrition Program [14] and a recent Food and Nutrition Policy [15].

In low and middle-income countries like Ethiopia, access to and availability of ASFs is usually limited for many children. According to the Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS), only 14% of children aged 6–23 months meet the minimum dietary diversity requirements. This report noted that only 8% of children consumed meat, fish, or poultry. It also showed that about 17 and 25% of children aged 6–23 months reported consumption of eggs and dairy products, respectively [16]. A study conducted in Tigray region also found that only 13% of the children 6–23 months old meet the WHO recommended dietary diversity [17]. One reason for the diets being extremely monotonous could be poor consumption of ASFs.

Various factors may influence the availability and consumption of ASFs by children. Factors that were associated with increased ASF consumption include increased child age, pastoral livelihood, Muslim religion, and participation in a Productive Safety Net Program [18]. Besides, villages in forested areas with wild animal populations, observing a large number of ceremonies of long duration, households with a greater number of small livestock, and women’s autonomy on decisions about livestock assets also were related to increased ASF intake [19].

Information regarding the magnitude and determinants of ASF consumption among children is inadequate at national level. Ethiopia is a country with diverse livelihoods, religions, and cultures that can affect consumption of ASFs among children. In an area with such socioeconomic and cultural diversity, much research on this topic is necessary to provide more conclusive information to establish effective interventions to improve dietary diversity and reduce stunting.

Therefore, with this study, we aimed to fill the gap of information regarding the consumption of ASF and the factors associated with it at the national level. The objective of this study was to determine the magnitude and factors associated with ASF consumption among children aged 6 to 23 months in Ethiopia.

Methodology

Data source and sample design

The analysis for this study was based on data extracted from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (2016 EDHS), which is the fourth in a series of Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in Ethiopia. This survey used a sampling frame of a complete list of 84,915 enumeration areas (EAs) created for the 2007 Ethiopia Population and Housing Census. An EA covers on average 181 households. The survey involved a two-stage stratified sampling. Each of the 11 administrative regions in the country was stratified into urban and rural areas, which resulted in 21 sampling strata. The first stage involved selection of 645 EAs with probability proportional to EA size and with independent selection in each sampling stratum. In the second stage, from the new hosehold list, a fixed number of 28 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability systematic selection.

Among the total 18,008 households selected for the sample, 17,067 were available during data collection, and 16,650 were successfully interviewed, giving a response rate of 98%. Among the 16,583 eligible women for individual interviews in the interviewed households, only 15, 683 were successful yielding a response rate of 95%. Women who had no less than one child living with them who was born in 2014 or later were asked questions about the types of liquids and foods the child had consumed in the 24 h before the survey. If mothers had more than one child aged 6–23 months, they were interviewed only about the youngest one [20]. Our analysis was done among last born living children aged 6–23 months that live with the respondent.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable for this study was consumption of ASF by children aged 6–23 months. It was categorized into “0”(No ASF consumption) and “1”(ASF consumption). The questionnaire asked mothers/caretakers the types of foods the child had eaten in the 24 h prior to the survey. Eggs, fish, yogurt, cheese, milk, meat (including beef, poultry, pork, lamb, and any other meat not mentioned), and organ meats (e.g., liver) were the ASFs included in the questionnaire. Consumption of any amount and/or type of the ASFs listed above was considered as ASF consumption.

Explanatory variables

Control variables were selected based on their hypothesized effect on the outcome variable and their availability in the data. Variables included in this analysis were child sex and age, respondent age, respondent educational status, respondent’s occupation, household total number of children, household assets, household wealth index, access to media at least once a week, religion, ownership of land usable for agriculture, and total number of livestock owned.

Child age was categorized into four groups (6–8 months, 9–11 months, 12–17 months, and 18–23 months). Respondent’s age was also a factor variable with three levels (15–24 years, 25–34 years, and 35–49 years). Educational status of respondents was dichotomized into no and any education. Ownership of household assets was determined from a summed score of a set of twelve assets including electricity, a watch or clock, a radio, a television, a mobile telephone, a non-mobile telephone, a refrigerator, a table, a chair, a bed with a mattress (cotton/sponge/spring), an electric mitad (a grill or cooktop used for preparing injera or bread), and a kerosene lamp/pressure lamp. Access to media was also dichotomized into exposure to media (reading newspaper, listening to radio, or watching television) at least once a week or not. Livestock ownership was taken into account if a household owns any livestock (cattle, cows/bulls, goat, sheep, chicken, or camel). Moreover, occupational status of respondents was categorized into three categories (Not working, agricultural works, and non-agricultural works).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using Stata version 14.0 after the complex sampling design was adjusted by applying sampling weights using the survey “SVY” command. Sampling weights were used to remove the probability of including an observation that would happen due to the complex sampling design and avoid potential bias. Before starting data analysis, data cleaning and selection of appropriate control variables were performed. Descriptive characteristics are presented as proportions (%) and means for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Multivariable logistic regression was then used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variables that satisfied the cutoff point of p-value ≤0.25 in the bivariate model were candidates for the multiple logistic regression model. Finally, only those variables with statistical significance of p < 0.05 were retained in the final model. Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to test model fitness. Multi-collinearity among independent variables was also assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF) and a value of 10 was used as cut off.

Results

Participant characteristics

Among the 2861 children in the sample, 50.4% were females and the mean age was 13.9 ± 5.1 months. Majority (87.9%) of the respondents lived in rural areas. The average age of parents/caregivers was 28.6 ± 6.6 years and about one-third reported having attained any formal education. About 40.2 and 34.4% of the surveyed households were Muslim and Orthodox Christians, respectively. Concerning educational status, 38.8% of the mothers/caregivers and 43.1% of the husbands received any form of education. Agricultural works represented 52 and 64% of the occupations of the mothers/caregivers and fathers of the children, respectively. The average number of assets a surveyed household-owned was 2.86 (out of potential 8). More than three quarters (77%) of the households owned land usable for agriculture. Similarly, about 73.4% of the surveyed households owned livestock. This study showed low exposure of mothers/caregivers to mass media. From the interviewed mothers/caregivers 80.7% have access to media less than once a week or do not have any kind of access to media at all. (Table 1).

Table 1: Household, caretaker, and child characteristics of children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia, n = 2861.

ASF consumption

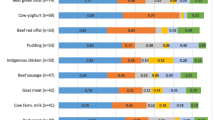

In the presented study, 46.5% (42.9, 50.2) children reported consuming any type of ASF. Besides, 38.2% (34.7, 41.9) reported consuming dairy (includes tinned, powdered or fresh milk, cheese, yogurt, or other milk products). Among the total number of children in the sample, 17% (95% CI 14.9, 19.4), 16.7% (95% CI 14.4, 19.3), and 13.7% (95% CI 11.6, 16.2) consumed egg, milk, and yogurt in the 24 h preceding the survey, respectively. Consumption of meat (6%) (95% CI 4.3, 8.4), organ meat (4%) (95% CI 3.0, 5.2, and fish (1.3%) (95% CI 0.6, 3.1) was very low (Fig. 1).

Consumption of ASF showed regional differences. Addis Ababa (79.7%), Somali (72.8%), and Harari (69.2%) regions had the highest proportions of children consuming ASFs. ASF consumption was low in Amhara (20.2%) and Benshangul-gumuz (28.2%) regions (Fig. 2).

About 50.9% of children from Muslim households consumed ASF. This is higher compared to that of children from orthodox (37.8%), and protestant (47.7%). However, among children who fall under the “Others” (n = 70) religion, 75% consumed ASF in the previous day of the survey. Children from mothers who obtained any education consumed ASF at higher rates (53.1%) than those from mothers with no education (42.4%). Besides, ASF consumption was higher in children from respondents that had access to media at least once a week (58.1%) in contrast to those from respondents that have access to media less than once a week or have not access at all (43.8%). Moreover, the mean number of assets and livestock owned by a household were both greater in the group consuming ASF.

Determinants of ASF consumption

The variables that passed the screening (p-value< 0.25) in the bivariate analysis include place of residence, religion, total number of household assets, total number of livestock owned by a household, ownership of land usable for agriculture, child age, child sex, age of respondent, educational status of the respondent, and respondent’s access to media at least once a week. Finally, five variables made up the final adjusted logistic regression model as determinants of ASF consumption (p-value< 0.05). (Table 2).

Compared to children from an orthodox family, the odds of ASF consumption were about six times, twice, and 70% higher in children from households with other (catholic, traditional, or others) (AOR = 5.80; 95% CI 1.64, 20.17), Muslim (AOR = 2.26; 95% CI 1.58, 3.23), and protestant (AOR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.16, 2.46) religions, respectively. Besides, the average number of household assets (AOR = 1.19; 95% CI 1.09, 1.30) and the average number of livestock owned by a household (AOR = 1.02; 95% CI 1.01, 1.03) were significant determinants of ASF consumption in the analyzed sample. Moreover, higher odds of ASF consumption were seen in children aged 9–11 months (AOR = 1.61; 95% CI 1.13, 2.28), 12–17 months (AOR = 1.44; 95% CI 1.06, 1.95), and 18–23 months (AOR = 1.53; 95% CI 1.11, 2.12) in contrast to the younger age group (6–8 months old children). Opposed to the positive associations described above, one variable was found to be negatively associated with the outcome variable. Children from households that own land usable for agriculture were 33% (AOR 0.67; 95% CI 0.51, 0.89) less likely to consume ASFs as compared to those from households that do not own land usable for agriculture. (Table 2).

The final model of this study indicated that there was no multicollinearity shown by a mean VIF value of 1.39. (Fig. 3). The significance level of Hosmer–Lemeshow test for goodness of fit was 0.34. Since this value is greater than 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis and this shows that there is no significant difference between the observed and model predicted values. Therefore, our final model fits the data well.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of the 2016 EDHS, which included a total of 2861 children aged 6–23 months, 46.5% reported consuming any type of ASF in the day prior to the survey. This is similar to a recent survey in Ethiopia that found a slightly higher magnitude (51%) of ASF consumption [18]. A survey in Kenya reported that less than 30 and 10% of children consumed flesh foods and eggs, respectively [21]. The lower magnitude in the latter study could be due to the absence of information on dairy consumption.

Religion, number of household assets, number of livestock owned by a household, ownership of land usable for agriculture, and child age are the five variables that were significantly associated with the outcome variable.

Children from orthodox family had lower odds of ASF consumption compared to children from other religions. Not differently, a study that assessed ASF consumption by children from four regions of Ethiopia found a 30% lower consumption in children from Orthodox households than children from Muslim households [18]. Throughout the year, Ethiopian Orthodox Christians have seven official fasting periods; All Wednesday and Fridays, except for the 50 days after Easter, the Lenten fast of 55 days, the Nineveh fast of 3 days, the vigils, or gahad of Christmas and epiphany, the 14–44 days fast of the apostles, the 43 days of the fast of the prophets, and the 15 days fast of the assumption in august. The average person may fast about 180 days, refraining from consuming ASF including meat, eggs, and milk [22]. During these extended time periods, a person is expected not to consume any food of animal origin. Although children are not supposed to fast, the limited availability of ASFs in the households they live during such periods may affect their consumption of those foods. The other reason that could affect ASF consumption by children is fear of contamination of cooking utensils and violation of religious rules and procedures by caregivers [23]. Notwithstanding the above explanations, a recent report by Alive and Thrive on IYCF practices, beliefs, and influences in Tigray region discussed that some mothers reported unaffordability and unavailability of meat and chicken in the market in fasting periods [24]. This could be due to the fact that ASFs especially meat are scarce and more expensive particularly during long periods of fasting like Lent in Orthodox communities because fasting adults are unwilling to slaughter animals [25].

Besides, children from households with higher numbers of livestock showed higher ASF consumption. Other studies found similar findings. Compared to households that did not own a particular livestock group, consumption of ASF during the 30 days before the survey was found to be significantly higher in households that owned the livestock group from which the food was derived [26]. Besides, according to a study in rural Uganda, promoting (small) livestock ownership significantly increased dairy consumption [27]. Moreover, in a study in rural Nepal, even low levels of poultry and cattle ownership were respectively associated with higher consumption of eggs and dairy among young children [28]. Ownership of livestock is also a positive facilitator of child dietary diversity [29]. These findings support the argument that households are utilizing livestock for own consumption. Therefore, such a positive association between livestock ownership and ASF consumption should be maintained by addressing socio-cultural norms and practices towards motives of livestock keeping, promoting good livestock rearing practices, improving market access, and filling gaps on nutrition importance of ASFs [30]. This is especially important in Ethiopia, a country known as one of the owners of huge number of livestock in the world [31].

In contrast to the findings in our study, a study by Kobina et al. noted that household ownership of any livestock, but not poultry, was associated with decreased consumption of ASFs [32]. The reason for this difference could be the higher ownership of free-range poultry compared to other livestock and the relatively very low sample size in the Kobina et al. study. Similarly, a study in Luangwa Valley, Zambia, found no significant association between livestock ownership and ASF consumption [33].

In this presented study, ASF consumption increased by nearly 20% with a unit increase in the number of household assets. This is similar to a study done in Indonesia in which increased value of household assets was significantly associated with ASF consumption [34]. Economic capability of households possesses a great role in determining the likelihood of ASF consumption [35]. Households with a higher number of assets (electricity, a television, a radio, mobile/non-mobile telephone, a refrigerator, a table, a chair, a bed with a mattress (cotton/sponge/spring), an electric mitad (a grill or cooktop used for preparing injera or bread), and a kerosene lamp/pressure lamp) may have a better opportunity to prepare and present ASFs on their table for consumption.

This study showed higher odds of ASF consumption among children in higher age categories. Similarly, in their study about ASF and child stunting, Headey et al. witnessed that consumption of any ASF and only dairy (consumption of meat, eggs, and fish were similar across age groups) increased with age [36]. The reason could be that as age is increasing, it is more likely feeding skills are improved and caloric needs are increased.

Nevertheless, children from households that own land usable for agriculture showed lower ASF consumption. This is challenged by a recent report by food and agriculture organization which states that the ownership, including its quality, of agricultural land is a major positive determinant of the relationship between crop and livestock production [37]. The reason for this negative association could be the fact that more than 72% of households that own land usable for agriculture in this study lie within the three lowest wealth quintles (middle, poorer, and poorest). These households are more likely to sell and/or exchange any of their livestock for other necessary goods than using for own consumption. In such households, ASFs are considered as luxury foods and usually are only consumed during holidays and special events.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strength of this study is that it utilized a large sample size and that the sampling technique (especially the use of sampling weights) allowed every household to have equal probability of inclusion. The larger sample size proved important in maintaining the internal validity of the study by helping provide precise descriptive and analytic findings. The other strength is that the data in this study were collected from all the regions in Ethiopia, which makes generalizability of the findings forward.

The crosssectional design of this study means it doesn’t show any cause and effect relationship between the outcome variable and the explanatory variables. Additionally, lack of information on possible explanatory variables like food insecurity status of the households may have changed the picture of the current associations between the variables. Therefore, incorporating a household food insecurity access score in future studies can be crucial in identifying other unseen associations. Another possible limitation is that this study did not provide information on the amount and frequency of ASF consumption. The use of 24-h dietary recalls may not perefectly tell about the usual diets (i.e., by creating within-person error) leading to an attenuation bias [38]. Therefore, future similar studies should consider and try to address the points raised.

Conclusions

In Ethiopia, consumption of ASFs among children aged 6–23 months is not adequate. Besides, child age, religion, household livestock ownership, household ownership of assets, and household ownership of agricultural land determine ASF consumption among children. The findings of this study imply that ASF consumption can be increased through integrated work on community factors like religion and programs focused on empowering households’ capability of owning livestock and other socioeconomic assets. This study may contribute to the growing body of research works about ASF provision to older infants and young children.

Availability of data and materials

Supporting data for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request. The EDHS data was retrived from https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ASF:

-

Animal source food

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- EA:

-

Enumeration areas

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian demographic and health surveys

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health surveys

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SVY:

-

Survey

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Martins VJB, Florê TMMT, Santos CDL, Vieira MDFA, Sawaya AL. Long-lasting effects of undernutrition. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;7:1817–46.

Unicef/ WHO/The World Bank. Levels and Trends in Child malnutrition - Unicef/WHO/The World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates, key findings of the 2019 edition. 2019;4.

Hoddinott JF, Rosegrant MW, Torero M. Investments to reduce hunger and undernutrition. 2012; Available from: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll5/id/3990

Bégin F, Aguayo VM. First foods: why improving young children’s diets matter. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(July 2017):1–9.

Rah JH, Akhter N, Semba RD, Pee SD, Bloem MW, Campbell AA, et al. Low dietary diversity is a predictor of child stunting in rural Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(12):1393–8.

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Animal-source Foods for Human and Planetary Health: GAIN’s Position; 2020. p. 11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.36072/bp.2

A.Nti C. Dietary diversity is associated with nutrient intakes and nutritional status of children in Ghana. Asian J Med Sci. 2011;2(1):105–9.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;382(9890):452–77.

Lassi ZS, Das JK, Zahid G, Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Impact of education and provision of complementary feeding on growth and morbidity in children less than 2 years of age in developing countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(SUPPL.3):S13 Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/S3/S13.

World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: definitions and measurement methods. Geneva; 2021.

Neumann C, Harris DM, Rogers LM. Contribution of animal source foods in improving diet quality and function in children in the developing world. Nutr Res. 2002;22(1–2):193–220.

Zhang Z, Goldsmith PD, Winter-Nelson A. The importance of animal source foods for nutrient sufficiency in the developing world: the Zambia scenario. Food Nutr Bull. 2016;37(3):303–16.

Grace D, Dominguez-Salas P, Alonso S, Lannerstad M, Muunda E, Ngwili N, et al. The influence of livestock- derived foods on nutrition during the first 1 , 000 days of life. ILRI Research report 44. Nairobi: Int Livest Res Inst; 2018.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, National nutrition coordination body: National Nutrition Program Multi-sectoral Implementation Guide June 2016 Foreword. 2016;(June).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Food and Nutrition Policy; Government of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa; 2018.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa and Rockville: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Hirvonen K, Wolle A. Consumption, production, market access and affordability of nutritious foods in the Tigray region of Ethiopia. Alive & Thrive and International Food Policy Research Institute: Addis Ababa; 2019.

Potts KS, Mulugeta A, Bazzano AN. Animal source food consumption in young children from four regions of ethiopia: Association with religion, livelihood, and participation in the productive safety net program. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):354.

Wong JT, Bagnol B, Grieve H, da Costa Jong JB, Li M, Alders RG. Factors influencing animal-source food consumption in Timor-Leste. Food Secur. 2018;10(3):741–62.

ECSA. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville: CSA and ICF; 2016. p. 161.

Dominguez-Salas P, Alarcón P, Häsler B, Dohoo IR, Colverson K, Kimani-Murage EW, et al. Nutritional characterisation of low-income households of Nairobi: socioeconomic, livestock and gender considerations and predictors of malnutrition from a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nutr. 2016;2(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-016-0086-2.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Faith and Order. Worship in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Available online: http://www.ethiopianorthodox.org/english/ethiopian/worship.html (accessed on 29 Mar 2020).

Haileselassie M, Redae G, Berhe G, Henry CJ, Nickerson MT, Tyler B, et al. Why are animal source foods rarely consumed by 6-23 months old children in rural communities of northern Ethiopia? A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):1–21.

Alive & Thrive. IYCF Practices, Beliefs, and Influences in Tigray Region , Ethiopia. 2010.

Bazzano AN, Potts KS, Mulugeta A. How do pregnant and lactating women , and young children , experience religious food restriction at the community level ? A qualitative study of fasting traditions and feeding behaviors in four regions of Ethiopia; 2018.

Hetherington JB, Wiethoelter AK, Negin J, Mor SM. Livestock ownership, animal source foods and child nutritional outcomes in seven rural village clusters in sub-Saharan Africa. Agric Food Secur. 2017;6(1):1–11.

Azzarri C, Zezza A, Haile B, Cross E. Does livestock ownership affect animal source foods consumption and child nutritional Status ? Evidence from rural Uganda. J Dev Stud. 2015;51(8):1034–59.

Broaddus-shea ET, Manohar S, Thorne-lyman AL, Bhandari S, Nonyane BA, Winch PJ, et al. Small-Scale Livestock Production in Nepal Is Directly Associated with Children ’ s Increased Intakes of Eggs. Nutrients. 2020;12:252.

Rakotonirainy NH, Razafindratovo V, Remonja CR, Rasoloarijaona R, Piola P, Raharintsoa C, et al. Dietary diversity of 6- to 59-month-old children in rural areas of Moramanga and Morondava districts, Madagascar. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):1–14.

Bundala N, Kinabo J, Jumbe T, Rybak C, Sieber S. Does homestead livestock production and ownership contribute to consumption of animal source foods? A pre-intervention assessment of rural farming communities in Tanzania. Sci African. 2020;7:e00252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00252.

Bachewe F, Minten B, Tadesse F, Taffesse AS. The Evolving Livestock Sector in Ethiopia. Growth by heads , not by productivity: IFPRI; 2018.

Kobina A, Id C, Wilson ML, Aryeetey RNO, Jones D. Livestock ownership , household food security and childhood anaemia in rural Ghana. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):1–14.

Dumas SE, Kassa L, Young SL, Travis AJ. Examining the association between livestock ownership typologies and child nutrition in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):1–21.

Iannotti L, Barron M, Roy D. Animal source food consumption and nutrition among young children in Indonesia: preliminary analysis for assessing the impact of HPAI on nutrition. DFID Pro-poor HPAI Risk Reduct Strateg Proj Res Rep. 2008;17:12–5.

Gittelsohn J, Vastine AE. Animal Source Foods to Improve Micronutrient Nutrition and Human Function in Developing Countries Sociocultural and Household Factors Impacting on the Selection , Allocation and Consumption of Animal Source Foods : Current Knowledge and Application 1. Am Soc Nutr Sci. 2003;3:4036–41.

Headey D, Hirvonen K, Hoddinott J. Animal sourced foods and child stunting. Am J Agric Econ. 2018;100(5):1302–19.

FAO. Africa Sustainable Livestock 2050 - Livestock sector development in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa - A comparative analysis of the drivers of livestock sector development; 2019. p. 34.

Thorne-Lyman A, Donna Spiegelman A, Fawz WW. Is the strength of association between indicators of dietary quality and the nutritional status of children being underestimated? Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(1):161–2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the DHS program for letting us access the EDHS data set.

Funding

All the authors dedicated their additional working hours to develop this paper without receiving any specific fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GG conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and drafted and finalized the manuscript. AM and AK assisted in conceptualizing the study and development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This secondary data for this analysis was obtained from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) online archive after our online request to access the data set was sent to the CSA or ORC Macro (Demographic and Health Survey) and has been approved.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebretsadik, G.G., Adhanu, A.K. & Mulugeta, A. Magnitude and determinants of animal source food consumption among children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia: secondary analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 22, 453 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12807-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12807-8