Abstract

Background

The primary aim of this study was to determine if screen use in early childhood is associated with overall vulnerability in school readiness at ages 4 to 6 years, as measured by the Early Development Instrument (EDI). Secondary aims were to: (1) determine if screen use was associated with individual EDI domains scores, and (2) examine the association between screen use and EDI domains scores among a subgroup of high screen users.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was carried out using data from young children participating in a large primary care practice-based research network in Canada. Logistic regression analyses were run to investigate the association between screen use and overall vulnerability in school readiness. Separate linear regression models examined the relationships between children’s daily screen use and each separate continuous EDI domain.

Results

A total of 876 Canadian participants participated in this study. Adjusted logistic regression revealed an association between increased screen use and increased vulnerability in school readiness (p = 0.05). Results from adjusted linear regression demonstrated an association between higher screen use and reduced language and cognitive development domain scores (p = 0.004). Among high screen users, adjusted linear regression models revealed associations between increased screen use and reduced language and cognitive development (p = 0.004) and communication skills and general knowledge domain scores (p = 0.042).

Conclusions

Screen use in early childhood is associated with increased vulnerability in developmental readiness for school, with increased risk for poorer language and cognitive development in kindergarten, especially among high users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The link between excessive sedentary behaviours and poor health outcomes across the lifespan is well-noted in the literature [1,2,3]. Early childhood is an important period in child development; high levels of daily sedentary behaviours may inimitably influence the health and learning outcomes during this period [4]. It is still unclear as to whether screen use should be touted as an aid or impediment during early childhood, and whether such decisions are dependent on the quantity or quality of screen use, or possibly both [5, 6]. A review (n = 76 studies) by Kostyrka-Allchorne et al. [7], which examined the association between television viewing, cognition and behaviour in children, reported that early onset of viewing and inappropriate content may be related to negative outcomes. A prospective longitudinal study by Pagani and colleagues [8] found that every additional hour of television exposure at 29 months corresponded to 7% and 6% unit decreases in classroom engagement and math achievement, respectively; and that exposure during this critical period may make a unique contribution to developmental risk. In contrast, review findings claim that educational TV may enhance learning, particularly for preschoolers [7]. Given the pervasiveness of screens among young children [9, 10], it is important to ascertain how screen time is associated with their development.

By school entry, researchers believe that close to 30% of Canadian children show some form of deficit or delay in developmental outcomes like language, socioemotional status, and communication [11, 12]. As concerns in early childhood development often worsen sans meaningful interference, the extent of children inadequately prepared for learning is worrisome [13] typically measured at school entry, school readiness centres around developmental areas related to children’s future success including physical, socioemotional, and language and cognitive factors [14].

Regardless the link between high screen use and negative physical and psychosocial outcomes in young children [15,16,17,18], mixed evidence concerning the use of screens for educational purposes may allude to some possible benefits of high-quality and interactive screen use [7, 19,20,21,22]. With the duration and availability of screen use increasing [23], as well as the context in which this screen-viewing takes places (intentional and unintentional exposure, background vs. foreground exposure, co-viewing, at home vs. school, etc.) [24, 25], many queries remain regarding their impact on children’s preparedness to begin their scholarly journey. Understandably, the link between screen use and development are complex and require further investigations; optimal child developmental trajectories and policy recommendations are dependent on the identification of modifiable behavioural factors in this young cohort.

Despite the growing pervasiveness of techno-dependence and screen use, there is limited evidence of its impact on school readiness or developmental health in young children. As such, the primary objective of this study was to determine whether screen use in early childhood was associated with overall vulnerability in school readiness at ages 4 to 6 years, as measured by the Early Development Instrument (EDI). Secondary objectives included determining whether screen use in early childhood was associated with scores in individual EDI domains as well as examining the association between screen use and scores in individual EDI domains in a subgroup of high screen users (exploratory).

Methods

Using data from 2013 to 2020, a prospective cohort study was conducted with children 12 months to 6 years, who were enrolled in a large Canadian primary care practice-based research network – TARGet Kids! (http://www.targetkids.ca) [26]. Children were recruited at any age up to the age of 6 and were then assessed annually at a scheduled health visit with their family physician until adolescence. Consent was obtained for all participants from their parent/guardian prior to enrollment. Institutional approval from the appropriate research ethics boards (The Hospital for Sick Children, Unity Health, and respective participating school boards) was received for study materials and protocols. The present paper adheres to STROBE Guidelines for Cohort Studies [27], and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Additional information regarding the cohort profile can be found elsewhere [28].

Eligibility Criteria

This study included children whose parents/guardians had completed questionnaires on screen use and had the EDI completed during the second half of the school year by their teacher in kindergarten (junior kindergarten or senior kindergarten). Children without chronic health conditions except for asthma, severe developmental delays prior to enrollment, had a gestational age ≥ 32 weeks, and had English-speaking parents/guardians who provided consent to participate were eligible to participate in the study.

Exposure Variable – Screen Use

The primary exposure of interest was children’s total daily screen use duration. These data were obtained from a standardized parent-reported questionnaire which was advised by the validated and long-standing Canadian Community Health Survey – a national cross-sectional survey that collects information related to health status, health care utilization and health determinants for the Canadian population [29]. Total daily screen use was derived by taking the sum of mean screen use (across all devices, e.g., TV, computer, video games, tablets, smartphones) during the week and weekend (i.e., average daily screen use on weekday*5 + average daily screen use on weekend day*2) / 7). Exposure data on screen use collected closest to the EDI outcome measure (but preceding it) were retained. Restricted cubic splines with 5 knots were used to test for non-linearity and to accommodate various shapes for the association of daily screen use in the models (p-value cut-off = 0.05).

Outcome Variable – School Readiness

Used worldwide, the EDI is a teacher-completed evaluation of school readiness which has been validated for use with children in kindergarten [11, 30, 31]. Specific to the Canadian province of Ontario, the kindergarten sample ranges from 3 to 6 years as kindergarten includes children in “junior kindergarten” (JK; where children enter in September of the calendar year they turn 4 years old) and “senior kindergarten” (SK; which children enter the year they turn 5). The EDI’s psychometric properties have been evaluated in Canada and in other countries, with scores being predictive of academic achievement and social relationships [11, 32,33,34,35]. The primary outcome of this study was children’s overall vulnerability on the EDI (0 = not vulnerable, 1 = vulnerable). Vulnerability was defined as being below the 10th percentile cut-off of a normative distribution on at least one of the EDI domains. Percentile cut-offs were based on published cut offs for SK [32] and JK [36].

The secondary outcome focused on the continuous scores on each of the EDI domains (0 = low ability to 10 = high ability). Specifically, the EDI is comprised of five developmental domains: emotional maturity (ability to think before acting, ability to deal with feelings at the age-appropriate level, ability to demonstrate empathetic responses to other people), communication skills and general knowledge (skills to communicate needs/wants in socially appropriate ways, symbolic use of language, storytelling, age-appropriate knowledge about the world around), physical health and well-being (gross and fine motor skills, adequate energy for classroom activities, independence in daily living skills), social competence (knowledge of acceptable public behaviour, ability to control own behaviour, appropriate respect for adult authority, cooperation with others, ability to play/work with others), and language and cognitive development (age-appropriate reading and writing skills, age-appropriate numeracy skills, ability to recite back specific pieces of information from memory) [11].

Confounding Variables

Identified a priori from the literature [5, 11, 37] and collected by a parent-reported child health questionnaire, the following confounding variables were included: child’s sex, age at outcome and physical activity level, as well as maternal ethnicity and education, annual household income, and follow-up time. Children with special needs were identified by teachers using special needs designation reports.

Statistical Analyses

R version 3.5.0 (R Core Team, Boston, MA) was used for all data cleaning and analyses [38]. Descriptive statistics were performed on of all variables entered into the models. Given the absence of accepted definitions or thresholds that identify ‘high screen users’ in this age group, histograms were used to examine the distribution of the screen use variable (exposure) and to determine the top 10% of screen users (i.e., high users) as a suitable cut-off. As some EDI data were collected during the second half of 2020, a sensitivity analysis was run to assess whether results meaningfully differed using the data collected pre- versus during the COVID-19 pandemic using an interaction with the primary exposure (total screen time).

To address the primary objective, odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were estimated from logistic regression analyses between total daily screen use and overall vulnerability in school readiness while adjusting for confounders. As informed by past research [39,40,41,42], interactions for sex and age with total daily screen use were included in the model [43, 44].

For the secondary objective, separate linear regression models were used to examine the relationships between children’s total daily screen use and each separate continuous EDI domain, adjusting for confounders. For the models of the continuous domain scores, a combination of bootstrap resampling and imputation (500 repetitions) was used to estimate the 95% confidence intervals and p-values for each model [45]. Specifically, bootstrap resampling was performed to address the non-normality of the residuals, and within each bootstrap resample we performed a single imputation to address missing covariate data. Imputations were performed using the mice package in R [46], as missing data was assumed to be missing-at-random (MAR). Reported missingness for each variable was under 15% [47]. Age and sex were entered as interaction terms [39,40,41,42]. Linear regression models were also used to investigate the associations between high users and each of the five EDI domains.

Results

A total of 876 children (329 in JK and 547 in SK) with complete outcome data at follow-up were included in the final analyses of this study (Fig. 1). The average participant age at exposure and outcome was 3.7 (SD = 0.4) years and 5.4 (SD = 0.3) years, respectively, with the mean duration between exposure and outcome being 11.3 (SD = 2.1) months. Approximately 52.8% of participants were male and 69.2% had mothers who self-reported European ethnicity (Table 1). Most parents who completed the survey had a college or university degree (91.6%) and 60.0% reported a household income below $150,000. Mean daily screen use was 4.8 (2.3) hours. The top 10% of daily screen users (n = 85), reported 8+ hours of daily screen use. A total of 131 participants (17%) were classified as “vulnerable” on the EDI tool.

Non-linear models were fitted using splines (p = 0.03). Total daily screen use was associated with overall vulnerability in school readiness as measured by the EDI (unadjusted OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.12 to 1.89, p < 0.001; adjusted OR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.54; p = 0.05; Table 2). It was estimated that the odds of being classified as vulnerable on the EDI are increased by 14% for every additional hour of screen use, after adjusting for the other variables in the model.

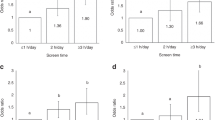

For the secondary analyses, increased daily hours of screen use was associated with reduced domain scores for language and cognitive development (Table 3; β= -0.73, 95% CI = -1.13 to -0.23, p = 0.004). There was no evidence of an association between total daily screen use and the other EDI domains (p > 0.05). Adverse associations emerged between high screen users (top 10%) and language and cognitive development domain (β = -0.227, 95% CI = -0.37 to – 0.07; p = 0.004), and the communication skills and general knowledge domain (β= -0.03, 95% CI = -0.06 to -0.001; p = 0.042; Table 4). There was no evidence of interaction effects by age or sex (p > 0.05) in any of the models (Supplementary Table 1). There were 139 participants whose EDI outcome data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic; we assessed whether results meaningfully differed using the data collected pre- and during the COVID-19 pandemic using a binary variable. Results from the sensitivity analyses (p = 0.67) suggested the data from these children be included..

Discussion

Healthy development in early childhood helps set the state for positive emotional, social, and physical well-being. Children who are vulnerable in the early years are more likely to have poor future educational outcomes and are at increased risk for health issues such as obesity, heart disease and poor mental health [48, 49]. In our sample, it was also determined that for every 1-hour increase in screen use, the odds of being classified as vulnerable increased by 14%. Also of note is that daily total mean screen use among participants was 4.8 h, which is consistent with national data reported by the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study which reported children spending 4.6 h per day in total screen-based pursuits [50].

Higher levels of screen use were associated (note the small effect size) with poorer scores in language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge. This finding is important as it highlights an adverse association between young children’s screen use and language skills and cognitive outcomes, two key attributes required for early academic success. Mechanisms to explain this finding may be reduced opportunities for parent-child interaction and play prior to school, which is critical for early language development [51]. Findings from Madigan et al. [5] systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 42 observational studies, n = 18,905 participants, < 12 years) revealed that higher levels of screen use were negatively associated with child language (r = −0.14; 95% CI, −0.18 to −0.10), supporting the findings of our study. Ribner et al. [52] also founds that television viewing was negatively associated with children’s school readiness skills, and this association increased as family income decreased. Interestingly, work by Linebarger and Vaala [53] found that the presence of a competent co-viewer may in fact boost very young children’s language learning from screen-viewing, much like the ways these processes facilitate learning in live scenarios.

Findings elicited from the examination between screen use and EDI outcomes among high screen users were in the anticipated direction, with increased screen use being associated with decreased language, communication, and cognitive domain scores. A review by Poitras et al. [2] (n = 96 studies) reported that increased screen use in children was weakly associated with delayed cognitive development and psychosocial health. Though examined among a slightly older age group (8-11 years), Walsh and colleagues reported that participants (n = 4,520) who met national screen use guidelines of ≤2 h/day displayed superior global cognition compared to those who did not [54], highlighting the importance of limiting excessive daily screen use in school aged children. Contrasting findings, however, were reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis (n= 58 studies) by Adelantado-Renau et al., which noted that the amount of time spent on overall screen media use was not associated with academic performance (ES = -0.29; 95% CI, -0.65 to 0.08), though the age span investigated was wide (4-18 years) [55]. The evidence to date is mixed, and while the previously listed studies do not provide evidence that could address the mechanism of the association between the screen use and poor language and cognitive outcome, they collectively suggest that when young children are observing screens, they may be missing important opportunities to master communication, interpersonal, and physical skills leading to developmental delays. For instance, when children use screens without an interactive or physical component, children are typically sedentary when they use screens potentially displacing opportunities to refine gross motor skills. Key to fostering optimal development in early childhood are the interactions between young children and their parents/guardians, teachers, or peers [48, 49]; unfortunately, screens have the propensity to limit such communication opportunities [50]. Consequently, it is possible that the outcomes in our study are the result of very similar pathways.

Strengths & Limitations

A strength of this study is the large sample size of young children followed prospectively, teacher-reported validated outcome measures of school readiness with cut points for vulnerability, and continuous domain scores. The methodological approaches utilized to account for non-normal residuals and missing data also served as an important strength of this paper. The chief limitation of this study was the use of parent-reported screen use data which may be subject to recall bias and an underestimation of children’s screen time [56]. As well, approximately 17% of the SK sample was classified as vulnerable per the EDI tool, which is lower than current provincial estimates of 29.4%, and thus potentially limiting the generalizability of our results [57]. Given the differences between some of the adjusted and unadjusted estimates, residual confounding should be highlighted as a possible limitation. Future studies may consider addressing mediating factors like sleep and weight status. The generalizability of these findings is limited by the fact that the majority of participants identified as having parents that were highly educated, earned higher incomes and were of European descent. As well, we relied on a single-use measure to assess children’s screen use, absent of collecting nuanced information regarding content or context.

Future Directions

Garnering more detailed data on the link between screen type or platform, screen content, and screen use duration may widen our comprehension of how screen use in the early years impacts school readiness, particularly given existing reports that support tentative positive outcomes of screen use among this young cohort (e.g., learning skills, face-to-face communication with educators and relatives, etc.). Likewise, it is also possible that some negative outcomes may also be driven by harmful screen content. In the context of COVID-19, there is a growing reliance on screen-based technology (e-learning, socialization, babysitting, etc.); consequently, finding novels ways to support screen use among young children to maximize the benefits and minimize the harms is particularly important [58]. While not a specific research objective in our study, the finding that there was no difference in the relationship between children’s screen use and EDI outcomes between 2020 and previous years is one that deserves further pursuit in the context of increased screen use through online learning (i.e., “virtual learning” or “e-learning”). Though some associations were found to be statistically significant in this study, they may not be clinically relevant; caution should be taken when interpreting the findings of this work given the small effect sizes reported. Lastly, to further expand the applicability of this work, future studies may consider running similar work with non-English speaking families to ascertain differences in impact of screen use on school readiness.

Conclusions

Children with higher screen time may be at risk of vulnerability in teacher reported developmental readiness for school in kindergarten, particularly with language and cognitive development. Stronger associations were seen among children who were high daily users of screens. Next steps include understanding the context, type, and quality of screen use and school readiness outcomes, to develop and evaluate focused interventions to maximize the benefits and minimize the harms associated with screen use in early childhood.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EDI:

-

early development instrument

- JK:

-

junior kindergarten

- SK:

-

senior kindergarten

References

Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunstan DW. Sedentary Behaviors and Subsequent Health Outcomes in Adults A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies, 1996-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004

Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Janssen X, Aubert S, Carson V, Faulkner G et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (0-4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5).

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Carson V, et al. Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0–4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37(2):370–380. https://doi.org/10.1139/h2012-019

Christakis D. The effects of infant media usage: what do we know and what should we learn? Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:8–16.

Madigan S, McArthur BA, Anhorn C, Eirich R, Christakis DA. Associations Between Screen Use and Child Language Skills. JAMA Pediatr. Published online March 23, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0327

Madigan S, Browne D, Racine N, Mori C, Tough S. Association Between Screen Time and Children’s Performance on a Developmental Screening Test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5056

Kostyrka-Allchorne K, Cooper NR, Simpson A. The relationship between television exposure and children’s cognition and behaviour: A systematic review. Dev Rev. 2017;44:19–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.12.002

Pagani LS, Fitzpatrick C, Barnett TA, Dubow E. Prospective associations between early childhood television exposure and academic, psychosocial, and physical well-being by middle childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(5):425–431. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.50

V. R. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by kids Zero to Eight. Common Sense Media. 2017;2.

Radesky JS, Christakis DA. Increased Screen Time. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(5):827–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.06.006

Janus M OD. Development and psychometric properties of the early development instrument (EDI): A measure of children’s school readiness. Can J Behav Sci. 2007;39:1–22.

Browne DT, Wade M, Prime H, Jenkins JM. School readiness amongst urban Canadian families: Risk profiles and family mediation. J Educ Psychol. 2018;110(1):133–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000202

Stanovich KE. Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy. Read Res Q. 1986;21(4):360–407. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.21.4.1

Cushon JA, Vu LTH, Janzen BL et al. Neighborhood poverty impacts children’s physical health and well-being over time: evidence from the early development instrument. Early Educ Dev. 2011;22:183–205.

Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA. Children’s Television Viewing and Cognitive Outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(7):619. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.7.619

Christakis DA, Ramirez JSB, Ferguson SM, Ravinder S, Ramirez J-M. How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: A review of results from observations in humans and experiments in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(40):9851–9858. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711548115

PAAVONEN EJ, PENNONEN M, ROINE M, VALKONEN S, LAHIKAINEN AR. TV exposure associated with sleep disturbances in 5- to 6-year-old children. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(2):154–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00525.x

Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA, Meltzoff AN. Associations between Media Viewing and Language Development in Children Under Age 2 Years. J Pediatr. 2007;151(4):364–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.071

Kirkorian HL, Choi K PT. Toddlers’ word learning from contingent and noncontingent video on touch screens. Child Dev. 2016;87(2):405–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12508

Staiano AE CS. Exergames for physical education courses: physical, social, and cognitive benefits. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5(2):93–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00162.x

Sweetser P, Johnson DM, Ozdowska A WP. Active versus passive screen time for young children. Aust J Early Child. 2012;37(4):94–98.

Radesky JS, Schumacher J ZB. Mobile and interactive media use by young children: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2251

Chaput JP, Colley RC, Aubert S, Carson V, Janssen I, Roberts KC TM. Proportion of preschool-aged children meeting the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines and associations with adiposity: results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey.:. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:147–154.

Strouse GA, Troseth GL, O’Doherty KD, Saylor MM. Co-viewing supports toddlers’ word learning from contingent and noncontingent video. J Exp Child Psychol. 2018;166:310–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.09.005

Barr R. Growing Up in the Digital Age: Early Learning and Family Media Ecology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2019;28(4):341–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419838245

Carsley S, Borkhoff CM, Maguire JL, et al. Cohort profile: The Applied Research Group for Kids (TARGet Kids!). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):776–788. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu123

STROBE. STROBE checklists (version 4). Published 2007. Accessed January 8, 2020. http://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=available-checklists.

Birken CS, Omand J, Nurse K, Borkhood C, Koroshegyi C, Lebovic G, Maguire J, Mamdani M, Randall Simpson J, Tremblay MS, Duku E, Reid-Westoby C JM. Fit for School Study Protocol: Early Child Growth, Health Behaviours, Nutrition, Cardiometabolic Risk, and Developmental Determinants of a Child’s School Readiness. BMJ Open. 2019;9(e030709). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030709

StatsCan. Canadian Community Health Survey.

Guhn M, Gadermann A ZB. Does the EDI measure school readiness in the same way across different groups of children? Early Educ Dev. 2007;18:453–472.

Janus M, Brinkman SA DE. Validity and Psychometric Properties of the Early Development Instrument in Canada, Australia, United States, and Jamaica. Soc Indic Res. 103AD;283.

Guhn M, Gadermann AM, Almas A et al. Associations of teacher-rated social, emotional, and cognitive development in kindergarten to self-reported wellbeing, peer relations, and academic test scores in middle childhood. Early Child Res Q. 2016;35:76–84.

Forer B ZB. Validation of multilevel constructs: validation methods and empirical findings for the EDI. Soc Indic Res. 2011;103:231–265.

Duku E, Janus M BS. Investigation of the cross-national equivalence of a measurement of early child development. Child Indic Res. 2015;8:471–489.

Curtin M, Madden J, Staines A et al. Determinants of vulnerability in early childhood development in Ireland: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002387–e002389.

Janus M, Pottruff M DE for the ET. Normative Parameters of the Early Development Instrument Data for the 4-Year-Old Cohort of Children.; 2021.

Webb S, Janus M, Duku E, Raos R, Brownell M, Forer B, Guhn M MN. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status indices and early childhood development. SSM- Popul Heal. 2017;3:48–56.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. Published 2020. Accessed November 4, 2020. https://www.r-project.org/

The Offord Centre for Child Studies. What can be done with EDI data? Early Development Instrument. Published 2019. https://edi.offordcentre.com/researchers/what-can-be-done-with-edi-data-2/

Wong RS, Tung KTS, Rao N, et al. Parent Technology Use, Parent-Child Interaction, Child Screen Time, and Child Psychosocial Problems among Disadvantaged Families. J Pediatr. 2020;226:258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.07.006

Ponti, M DHTF. Digital Media: Promoting Healthy Screen Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents.; 2019. https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/digital-media

Canadian Paediatric Society. Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford). Published online 2017:461–468.

Chittleborough CR, Searle AK, Smithers LG, Brinkman S, Lynch JW. How well can poor child development be predicted from early life characteristics? Early Child Res Q. 2016;35:19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.10.006

LAROUCHE R, BLANCHETTE S, FAULKNER G, RIAZI N, TRUDEAU F, TREMBLAY MS. Correlates of Children’s Physical Activity. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2019;51(12):2482–2490. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002089

Shao J, Sitter RR. Bootstrap for Imputed Survey Data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2016;91(435):1278–1288.

Buuren S van, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice:Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03

Li X, Keown-Stoneman CDG, Lebovic G, et al. The association between body mass index trajectories and cardiometabolic risk in young children. Pediatr Obes. Published online 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12633

Hertzman C. The state of child development in Canada: are we moving toward, or away from, equity from the start? Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14(10):673–676. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/14.10.673.

Kirkorian HL, Pempek TA, Murphy LA, Schmidt ME, Anderson DR. The impact of background television on parent-child interaction. Child Dev. 2009;80(5):1350–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01337.x.

ParticipACTION. 2020 ParticipACTION Report Card on Physical Activity for Chilldren and Youth. 2020.

Courage ML HM. To watch or not to watch: infants and toddlers in a brave new electronic world. Dev Rev. 2010;30:101–115.

Ribner A, Fitzpatrick C, Blair C. Family Socioeconomic Status Moderates Associations Between Television Viewing and School Readiness Skills. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38(3):233–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000425

Linebarger DL, Vaala SE. Screen media and language development in infants and toddlers: An ecological perspective. Dev Rev. 2010;30(2):176–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2010.03.006

Walsh JJ, Barnes JD, Cameron JD, et al. Associations between 24 hour movement behaviours and global cognition in US children: a cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2018;2(11):783–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30278-5

Adelantado-Renau M, Moliner-Urdiales D, Cavero-Redondo I, Beltran-Valls MR, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Álvarez-Bueno C. Association Between Screen Media Use and Academic Performance Among Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(11):1058. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3176

Radesky JS, Weeks HM, Ball R, et al. Young Children’s Use of Smartphones and Tablets. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20193518. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3518

The Offord Centre for Child Studies. EDI in Ontario. Early Development Instrument. Published 2019. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://edi.offordcentre.com/partners/canada/edi-in-ontario/#Vulnerability

Rhodes RE, Guerrero MD, Vanderloo LM, Barbeau K, Birken CS, Chaput JP, Faulkner G, Janssen I, Madigan S, Mâsse LC, McHugh TL, Perdew M, Stone K, Shelley J, Spinks N, Tamminen KA, Tomasone JR, Ward H, Welsh F TM. Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(74).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants and their families for their participation in this study as well as to all collaborators who are currently involved in the TARGet Kids! practice-based research network as outlined below:

Co-Leads: Catherine S. Birken, Jonathon L. Maguire; Advisory Committee: Ronald Cohn, Eddy Lau, Andreas Laupacis, Patricia C. Parkin, Michael Salter, Peter Szatmari, Shannon Weir; Science Review and Management Committees: Laura N. Anderson, Cornelia M. Borkhoff, Charles Keown-Stoneman, Christine Kowal, Dalah Mason; Site Investigators: Murtala Abdurrahman, Kelly Anderson, Gordon Arbess, Jillian Baker, Tony Barozzino, Sylvie Bergeron, Dimple Bhagat, Gary Bloch, Joey Bonifacio, Ashna Bowry, Caroline Calpin, Douglas Campbell, Sohail Cheema, Elaine Cheng, Brian Chisamore, Evelyn Constantin, Karoon Danayan, Paul Das, Mary Beth Derocher, Anh Do, Kathleen Doukas, Anne Egger, Allison Farber, Amy Freedman, Sloane Freeman, Sharon Gazeley, Charlie Guiang, Dan Ha, Curtis Handford, Laura Hanson, Leah Harrington, Sheila Jacobson, Lukasz Jagiello, Gwen Jansz, Paul Kadar, Florence Kim, Tara Kiran, Holly Knowles, Bruce Kwok, Sheila Lakhoo, Margarita Lam-Antoniades, Eddy Lau, Denis Leduc, Fok-Han Leung, Alan Li, Patricia Li, Jessica Malach, Roy Male, Vashti Mascoll, Aleks Meret, Elise Mok, Rosemary Moodie, Maya Nader, Katherine Nash, Sharon Naymark, James Owen, Michael Peer, Kifi Pena, Marty Perlmutar, Navindra Persaud, Andrew Pinto, Michelle Porepa, Vikky Qi, Nasreen Ramji, Noor Ramji, Danyaal Raza, Alana Rosenthal, Katherine Rouleau, Caroline Ruderman, Janet Saunderson, Vanna Schiralli, Michael Sgro, Hafiz Shuja, Susan Shepherd, Barbara Smiltnieks, Cinntha Srikanthan, Carolyn Taylor, Stephen Treherne, Suzanne Turner, Fatima Uddin, Meta van den Heuvel, Joanne Vaughan, Thea Weisdorf, Sheila Wijayasinghe, Peter Wong, John Yaremko, Ethel Ying, Elizabeth Young, Michael Zajdman; Research Team: Farnaz Bazeghi, Marivic Bustos, Charmaine Camacho, Dharma Dalwadi, Christine Koroshegyi, Tarandeep Malhi, Sharon Thadani, Julia Thompson, Laurie Thompson; Project Team: Mary Aglipay, Imaan Bayoumi, Sarah Carsley, Katherine Cost, Anne Fuller, Laura Kinlin, Jessica Omand, Shelley Vanderhout, Leigh Vanderloo; Applied Health Research Centre: Christopher Allen, Bryan Boodhoo, Olivia Chan, David W.H. Dai, Judith Hall, Peter Juni, Gerald Lebovic, Karen Pope, Kevin Thorpe; Mount Sinai Services Laboratory: Rita Kandel, Michelle Rodrigues.

Funding

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; grant number 133585). LMV was supported by a CIHR Fellowship Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Vanderloo conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the original analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Birken, Maguire, and Janus conceptualized and designed the study as well as reviewed the manuscript. Drs. Keown-Stoneman and Lebovic provided statistical guidance and reviewed the manuscript. Drs. Omand, Borkhoff, Duku, Mamdani, Parkin, Randall Simpson, and Tremblay consulted on study conceptualization and design as well as reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study and supporting material was received from the Hospital of Sick Children’s Research Ethics Board (Toronto, CANADA), Unity Health Toronto, and the respective participating school boards. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PCP reports receiving a grant from Hospital for Sick Children Foundation during the conduct of the study. PCP reports receiving the following grants unrelated to this study: a grant from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN # 115059) for an ongoing investigator-initiated trial of iron deficiency in young children, for which Mead Johnson Nutrition provided non-financial support (Fer-In-Sol® liquid iron supplement) (2011-2017); and peer-reviewed grants for completed investigator-initiated studies from Danone Institute of Canada (2002-2004 and 2006-2009), Dairy Farmers of Ontario (2008-2010). JLM received an unrestricted research grant for a completed investigator-initiated study from the Dairy Farmers of Canada (2011-2012) and D drops provided non-financial support (vitamin D supplements) for an investigator-initiated study on vitamin D and respiratory tract infections (2011-2015). CMB reports previously receiving a grant for a completed investigator-initiated study from the SickKids Center for Health Active Kids (2015-2016) involving the development and validation of a risk stratification tool to identify young asymptomatic children at risk for iron deficiency. These agencies had no role in the design, collection, analyses, or interpretation of the results of this study or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vanderloo, L.M., Janus, M., Omand, J.A. et al. Children’s screen use and school readiness at 4-6 years: prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 22, 382 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12629-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12629-8