Abstract

Background

Physical activity (PA) may best be promoted to patients during clinical consultations. Few studies investigated the practice of PA advice given by physicians, especially in China. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and contents of PA advice given by physicians in China and its association with patients’ characteristics.

Methods

Face-to-face questionnaire asking the prevalence and contents of PA advice given by physicians was administered to adult patients in three major hospitals in Shenzhen, China. Attitude of compliance, stature, PA level, and socio-demographic information were also collected. Data was analyzed via descriptive statistics and binary logistic regression.

Results

Of the 454 eligible patients (Age: 47.0 ± 14.4 years), only 19.2% (n = 87) reported receiving PA advice, whereas 21.8%, 23.0%, 32.2%, and 55.2% of patients received advices on PA frequency, duration, intensity, and type, respectively. Male patients were more likely to receive PA advice from physicians [odds ratio (OR): 1.81; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.08–3.05], whereas patients who were unemployed (OR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.04–0.67), and who already achieved adequate amount of PA (OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.12–0.71) were less likely to receive PA advice.

Conclusions

Prevalence of physicians providing physical activity advice to patients is low, there is a pressing need to take intervention measures to educate healthcare providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death worldwide [1]. In 1990, > 28 million global deaths were due to chronic disease [2], which increased to 39.5 million deaths in 2016 [3]. Furthermore, three quarters of all deaths attributed to chronic diseases occurred in low- and middle-income countries [4]. For instance, China, a middle-income country, chronic diseases accounted for 86.6% of mortality in 2015 [5]. This chronic disease pandemic imposes a great burden to the healthcare system and effective interventions are imperative to alleviate the current situation [6].

Physical activity (PA) reduces the incidence and complications of chronic diseases among adults and offers other multiple health benefits including the prevention and treatment of psychiatric diseases, neurological diseases, pulmonary diseases, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, and cancer [7, 8]. In contrast, physical inactivity is responsible for almost one sixth of the direct (medical) and indirect (non-medical) yearly costs for the management of chronic diseases [9]. Despite its health and economic benefits, participation in PA among Chinese adults remains low [10].

Physicians are influential sources of health information [11]. The Exercise is Medicine (EIM) initiative, developed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Medical Association (AMA), calls upon physicians to address the physical inactivity pandemic in patients with chronic diseases by assessing PA levels, providing PA counselling and referring patients to PA resources [12]. Numerous studies have evaluated PA promotion (i.e., prescription and referral) in primary health care setting, concluding that PA promotion delivered via healthcare providers in clinical settings is effective to increase patients’ PA levels and improve their health outcomes [13,14,15].

Although PA promotion in clinical settings is effective, only a small number of patients received PA advice from their healthcare providers in western countries. It was reported that only 18.0, 32.8, and 56.0% of patients received PA advice from healthcare providers in Australia, Germany, and United States (U.S.), respectively [16,17,18]. Reasons for not recommending PA to patients are often related to limited consultation time and insufficient education in EIM, competing priorities during clinical consultations, and perceiving a lack of motivation in patients [19]. Other studies examined patients’ characteristics associated with the receipt of PA advice. In Australia, patients with a lower physical and mental health-related quality of life score and/or with chronic diseases were more likely to receive PA advice [16]. Similarly, in U.S., patients who were male, non-married, lower-educated, Spanish-speaking, and with no chronic conditions were less likely to receive PA advice [20].

The prevalence of PA advice and its associated patients’ characteristics are understudied in Eastern countries like China. Furthermore, only a few studies investigated the contents of PA advice being provided to patients [16, 21, 22]. Specific contents of PA advice should contain exercise type, intensity, frequency and duration of activities. PA advice lacking specific contents may limit the health impact to patients [16]. Therefore, the present study aimed to: 1) investigate the prevalence of PA advice in patients with chronic diseases in China (primary outcome); 2) describe the content of PA advice that patients with chronic disease receive and examine whether such PA advice was adequate as defined by the current PA guideline (secondary outcome) [23]; and 3) identify patients’ factors that were associated with the receipt of PA advice (secondary outcome).

Methods

Study population

Adult patients with chronic diseases were recruited from the three largest general hospitals in Shenzhen, China to participate in an in-person survey. These hospitals were selected because of their high patient volume. Patients were interviewed immediately after their visit with the physician, outside the clinic consultation room, in a randomized order.

Patients that met the following inclusion criteria were included in the study: 1) ≥18 years of age, 2) presence of chronic disease (i.e diseases that identified by EIM) [24], 3) who were able to complete a face-to-face survey verbally. Exclusion criteria included: 1) patients with aneurysm, cardiac pacemaker, mobility limitations, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), 2) pregnancy, or 3) patients who were hospitalized.

Patients with chronic disease were identified through the following series of questions: “Did you see a physician?” Those who answered “yes” were further asked, “What is your primary purpose for your visit to physicians?” Patients who self-reported having a chronic disease, including heart disease (heart failure), peripheral arterial disease, hypertension, pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes, blood lipid disorders, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, low back pain, fibromyalgia, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), cancer (colorectal cancer, prostatic cancer and breast cancer), depression or anxiety, chronic kidney or liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease were invited to participate in the study [24].

By assuming the prevalence of PA advice was 50% (which would require the largest sample size), with a precision/absolute error of 5%, and at type I error of 5%, a total of 385 patients were required as according to the Charan and Biswas formula [25] for sample size calculation: Sample size = [(Z1-α/2)2p(1-p)]/d2, in which Z1-α/2 is standard normal variate (1.96 were used), p is expected proportion of patients received PA advice (i.e., 50%), and d is absolute error/precision (i.e., 0.05).

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. All participation was voluntary and no incentive was involved. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Reference number. SBRE-20-026). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Development of the questionnaire

Data were collected between September 2020 and October 2020. A total of 454 patients completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed based on the Anderson’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use, items from the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) questionnaire and previously published surveys from Canada and Australia [16, 26,27,28,29,30]. Anderson’s Behavioral Model was initially developed to understand how and why individuals use health services. It has been used in several areas of healthcare utilization and in relation to different type of diseases, such as predicting receipt of PA advice [18, 31, 32]. The final questionnaire consisted of 25 questions including multiple choice, dichotomous and open-ended items that explored the patients: 1) medical diagnosis, 2) socio-demographic characteristics, 3) anthropometric measurements, 5) self-reported PA levels, 5) receipt of PA advice from their physicians, and 6) likelihood of patients follow PA advice from their physicians. The questionnaire can be found at Additional file 1.

Measures

Physical activity advice

The presence of PA advice was detected by the following question: “Did the physician provide PA advice to you just now?” Those who answered “yes” were then asked about the details of the advice including its frequency (i.e., number of times per week), its intensity (i.e., low, moderate or high intensity), its duration (i.e., minutes per session) and its type (e.g., walking, Taichi, square dance … etc).

Likelihood of patients following PA advice from their physician

Patients who received PA advice from their physicians were asked “How likely is it that you will follow the PA advice given by your physician?” Response options included, “I will follow the advice”, “I will not follow their advice”, and “I don’t know”.

Anthropometric measurements

Height (cm) and weight (kg) were self-reported and used to calculate body mass index (BMI) [33]. Patients were classified as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 to 22.9 kg/m2), overweight (23.0 to 24.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥25 kg/m2), according to latest relevant World Health Organization (WHO) guideline [34].

Current PA behavior

Patients were asked whether they participated in PA within the last 6 months. Patients who answered “yes” were then further queried about the frequency, intensity, duration, and type of their regular PA. Patients who reported having regular moderate to vigorous intensity PA (MVPA), they were further being prompted to provide the total number of minutes they engaged in MVPA. Patients were then categorized into (i) patients who achieved adequate PA and patients who did not, according to the latest WHO guideline (i.e., engaging in 150 min of moderate to vigorous PA per week) [23].

Socio-demographic information

Socio-demographic information collected from the patients included gender, age, employment status (employed/unemployed/retired), and educational attainment (less than primary education/primary education/secondary education/college or associated degree/bachelor degree or higher). Familiarity with the hospital team was estimated by the number of years as a patient in the corresponding hospital as previous work has found this measure to be associated with health services utilization [30, 31].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as a percentage. To detect whether physicians’ PA advice was adequate according to the current global PA guideline, each item (frequency, intensity, duration, and type) was coded according to the WHO PA guideline for individuals with chronic conditions [23]. Advice that received all four points should be in accordance to the aerobic PA guideline [aerobic activity (type: 1 point), over the course of a week (frequency: 1 point), at a moderate or vigorous intensity (1 point), for at least 75 min (if vigorous intensity) or 150 min (if moderate intensity) (time: 1 point)] [35]. Logistic regression analyses (unadjusted and adjusted) were utilized to identify factors associated with the presence of PA advice. The following independent variables were included: gender, age, employment status, educational attainment, BMI, years as a patient, and whether the patient met PA guideline within the last 6 months. Age and years as a patient were dichotomized based on their means for regression analysis. Univariate models were first obtained for each independent factor. The final adjusted model included all independent factors with a p-value < 0.15. A forward logistic regression was then utilized to identify factors significantly associated with receiving PA advice from physicians. Data analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant in the final logistic regression model.

Results

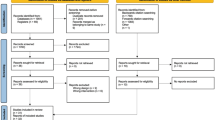

Out of 670 patients contacted, 187 patients were excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria, not have sufficient time for completing the questionnaire, or not interested in the survey (Fig. 1). Out of the 483 patients who completed the survey, 29 were further excluded for incomplete information, resulting in a final sample size of 454 for analysis (response rate = 67.8%).

The mean age of the respondents (N = 454) was 47.0 ± 14.4 years-old. A majority of respondents were women (51.3%, n = 229) and were employed (69.0%, n = 298). Those who completed post-secondary education accounted for 47.7% (n = 215) whereas secondary school 32.6% (n = 147). A total of 19.4% (n = 88) and 26.2% (n = 119) of the respondents were classified as overweight and obese, respectively. Furthermore, 18.3% (n = 76) of the respondents met PA guidelines within the last 6 months (Table 1).

Prevalence and associated factors of PA advice

The prevalence of receiving PA advice was 19.2% (n = 87 out of 454). Less than one-fifth of patients received PA advice during physician visits. Among the 87 patients who received PA advice, 50 (57.5%) of them reflected that they would follow the physician’s PA advice, whereas only 8 (9.2%) of them reflected that they wouldn’t follow. The rest (n = 29, i.e. 33.3%) were either “don’t know” or “not sure” (Fig. 2).

In the univariate analysis, participants who were unemployed [odds ratio (OR): 0.29; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.10–0.84], had longer time as a patient (OR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.28–0.88), and had adequate PA in the last 6 months (OR: 0.30; 95% CI:0.13–0.73) were less likely to receive PA advice from their physicians (p < 0.05) (Table 2). In the logistic regression model, male patients were more likely to receive PA advice (OR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.08–3.05), whereas unemployed patients (OR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.04–0.67) and who had adequate PA in the last 6 months (OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.12–0.71) were less likely to receive PA advice from their physicians (Table 2).

Details of PA advice

Among those who received PA advice, very few instances of PA advice (9.2%, n = 8) provided by physicians contained all of the important elements of PA prescription (i.e., frequency, intensity, duration and type). Although the type of exercise was most frequently specified (55.2%, n = 48), most PA advice was missing either frequency, intensity or duration (Table 3). When details on frequency, intensity or duration were given, most included suboptimal intensity (i.e., low intensity) and duration (i.e., < 30 min per session). Aerobic activities were most frequently recommended than other types of activity (Table 3).

Of the 87 patients who received PA advice, only two patients (2.3%) received comprehensive recommendations in accordance with the WHO aerobic PA and muscle-strengthening PA guidelines (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study investigated the prevalence of PA advice received by patients with chronic diseases, and key factors associated with the provision of this advice. To address limitations in previous studies, we also report on the content of the PA advice being given by physicians, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously examined in China.

A main finding of our study is that less than one-fifth of the patients (19.2%) reported receiving PA advice from their physician. Among them, only two patients received full-details of PA advice from their physicians. This prevalence of PA advice is lower than that reported in other countries, where a total of 31.0%, 32.8%, and 57.7% of patients reported receiving PA advice in United Kingdom (UK), Germany and U.S., respectively [17, 36, 37]. The heterogeneous questions used in these studies to quantify the level of PA advice may be responsible for these varying outcomes. In several studies, participants were commonly asked ‘has a healthcare provider advised you to exercise within the past 12 months’ [11, 38, 39]; whereas in the current study, patients were asked whether they were advised to exercise by their physicians. It is possible that other healthcare providers (e.g., nurses) may have provided our patients with PA advice during their hospital visits. Moreover, the low prevalence of giving PA advice may reflect the fact that exercise prescription in clinical setting has not yet receive much attention in China. Unlike the Green Prescription (GRx) project of New Zealand and the National Physical Activity Plan of U.S. [40, 41], which were well-promoted since 1998 and 2007, respectively, the importance of exercise advice in clinical setting was recently being emphasized in the “Healthy China 2030 Plan” [42].

Perhaps one encouraging result from this study, was that nearly 60% of respondents (57.5%, n = 50/87, Fig. 2) indicated willingness to follow the physician’s PA advice if provided, versus only 9.2% (n = 8/87) indicated not willing to follow physician’s PA advice. Such a large gap suggested that physician’s PA advice is a powerful channel to motivate PA participation among patients. Similar to previous ACSM survey reported that 65% of American who visited doctors indicated willingness to follow PA advice [43], which was considered much higher than most other exercise promotion campaigns. However, the finding need to be interpreted with cautious, as there may be social desirability bias. It is unfortunate that only 19.2% of the physicians in China prescribed PA advice, there may be a high chance of success (i.e. increase PA practice) if more physicians in China learned and are willing to prescribe PA to their patients.

The present study revealed that patients who were male were more likely to receive PA advice from their physician. This finding is consistent with previous studies involving adults of different ages [17, 30, 44]. It was reported that the prevalence of mortality from chronic diseases and obesity in Chinese men was much higher than women, it is logical that physicians in China tended to provide more suggestions, such as PA advice, to men more than women [45, 46]. Another large scale PA survey on Chinese community age 35–74 years revealed that the prevalence of leisure time PA in Chinese men, both from rural and urban areas, were much higher than women (OR = 1.16 to 2.26, p < .001 to .05, across various age groups) [47], hence physicians may have stronger confidence and motivation to prescribe PA for male patients due to the higher readiness in male patients.

Association between employment status and receiving PA advice was not found in American patients [18, 21, 48]. In contrast, unemployed patients in the current study were less likely to receive PA advice from their physicians. Reason for the impact of employment status in Chinese patients on receiving PA advice is unclear, however, it may be related to the income status. A recent review suggests that higher income is likely to induce Chinese individuals to utilize healthcare services including access to PA facilities (e.g., health club membership) [49], unemployed Chinese may have limited resource to access PA due to lower social economic status (SES). Physicians may therefore hesitate to provide PA advice to patients with lower SES. Further study is needed to verify the association between SES and physician’s advice on PA.

Lastly, the present study revealed that meeting PA guidelines within the last 6 months was negatively associated with receiving PA advice. This result is consistent with several other studies, that suggest sedentary patients are more likely to receive PA advice [38, 50, 51]. These findings suggest that physicians are promoting PA to patients who may benefit most from the recommendation [37, 52]. Conversely, in Brazil, patients reported having leisure-time PA were more likely to receive PA advice [53, 54]. Similarly, patients with higher PA levels tend to initiate more conversations with their providers about PA compared to those with poorer lifestyle habits [55].

We found that only 9.2% patients reported receiving complete PA advice (including frequency, intensity, duration and type) from their physicians. The lack of completed PA guidance may suggest that Chinese physicians do not receive sufficient training on exercise prescription. Previous studies suggest that healthcare providers may feel uncomfortable or lack confidence in giving specific rather than general advice [56, 57]. Other barriers to providing specific advice may include limited consultations time, lacking resources, or negative attitude toward the effectiveness of PA promotion [16]. Given the greater effectiveness of detailed PA recommendations, frequency, intensity, duration, and type should be incorporated into PA promotion practices [58].

Findings from the present study showed that a majority of patients (25.0%) were advised to participate in walking, which is generally consistent with previous studies [22, 29]. This finding may be related to the time constraints of the physicians. In China, physicians typically see up to 40 patients per day, necessitating that PA advice be quick and easily understood [59]. Instruction on walking can be given fairly quickly without much explanation in a busy clinical setting [21]. Besides walking, physicians should also learn other effective types of physical activities for patients such as resistance training and aquatic exercise.

This is the first study to investigate the prevalence of PA advice provision for patients with chronic diseases in China. The receipt of PA advice was captured at the completion of the clinic visit, reducing the risk of recall bias. Furthermore, the individual components of the PA advice were examined in this study, providing a glimpse into the type and quality of PA advice being provided to patients by their physicians.

However, there are some limitations with this study that deserve mention. The results of the study are based on self-reported data, which may lead to an overestimation of the prevalence rates of PA advice due to social desirability bias. Additionally, there may be other factors, not captured by this survey, that influence the receipt of PA advice, such as characteristics of the healthcare providers or the self-rated health status of the patients [30]. Only the provision of physicians’ advice collected from the out-patient clinics of the three major hospitals in Shenzhen China were involved, the total number of physicians involved was not known and was estimated at around 76 physicians according to the hospitals’ website. Cautious should be made as results we discussed only applied to these out-patient physicians. Another limitation is that the medical condition (i.e., acute or severe health issues) of the patients may make PA advice inappropriate, leading to an underestimation of correctly provided PA advice. Further, only three general hospitals in Shenzhen were selected may limit the external validity of our results. However, the included hospitals were major hospitals that provide services to majority of patients with various health conditions. The health services provided were similar to other general hospitals in Shenzhen, China. It is important to note that the objective of the study was to explore the provision of PA advice given by physicians from the perspective of patients, the actual practice and attitude of providing PA advice from the physician’s perspective is unknown and separate investigation is needed.

Conclusions

Only a small proportion of patients are receiving PA advice and guidance from their physicians in healthcare settings in Shenzhen, China. In patients who received PA advice, frequency, intensity, duration, and type of activity were not commonly provided. Although patients who are most likely to benefit from PA reported receiving advice at a greater rate, there is still much room for improvement [18]. Comprehensive initiatives, such as EIM, can provide reference and guidance to improve the PA counselling practices of physicians in healthcare settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACSM:

-

American College of Sports Medicine

- AMA:

-

American Medical Association

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

- EIM:

-

Exercise is Medicine

- GRx:

-

Green Prescription

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MVPA:

-

Moderate to vigorous intensity PA

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SES:

-

Social economic status

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- U.S.:

-

United States

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–504 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2.

GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–210 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#tab=tab_1. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

Kong LZ. China’s medium-to-long term plan for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases (2017-2025) under the healthy China initiative. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2017;3(3):135–7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdtm.2017.06.004.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases 2018. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Adivisory Committee. 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory committee scientific report. Wahington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(Suppl 3):1–72 https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12581.

Zhang J, Chaaban J. The economic cost of physical inactivity in China. Prev Med. 2013;56(1):75–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.11.010.

Zou Q, Wang H, Du W, Su C, Ouyang Y, Wang Z, et al. Trends in leisure-time physical activity among Chinese adults— China, 2000–2015. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(9):135–9 https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2020.03711.

Barnes PM, Schoenborn CA. Trends in adults receiving a recommendation for exercise or other physical activity from a physician or other health professional. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;86:1–8.

Lobelo F, Stoutenberg M, Hutber A. The Exercise is Medicine Global Health Initiative: a 2014 update. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(22):1627–33 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093080.

Anokye NK, Lord J, Fox-Rushby J. Is brief advice in primary care a cost-effective way to promote physical activity? Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(3):202–6 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092897.

Gallegos-Carrillo K, Garcia-Pena C, Salmeron J, Salgado-de-Snyder N, Lobelo F. Brief counseling and exercise referral scheme: a pragmatic trial in Mexico. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2):249–59 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.021.

Sanchez A, Bully P, Martinez C, Grandes G. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion interventions in primary care: a review of reviews. Prev Med. 2015;76(Supplement):56–67 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.012.

Short CE, Hayman M, Rebar AL, Gunn KM, De Cocker K, Duncan MJ, et al. Physical activity recommendations from general practitioners in Australia. Results from a national survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(1):83–90 https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12455.

Hinrichs T, Moschny A, Klaassen-Mielke R, Trampisch U, Thiem U, Platen P. General practitioner advice on physical activity: analyses in a cohort of older primary health care patients (getABI). BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-26.

Austin S, Qu HY, Shewchuk RM. Age bias in physicians’ recommendations for physical activity: a behavioral model of healthcare utilization for adults with arthritis. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(2):222–31 https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.10.2.222.

Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Verheijden MW, van der Zouwe N, de Vries JD, Middelkoop BJC, et al. Factors influencing primary health care professionals’ physical activity promotion behaviors: a systematic review. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(1):32–50 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-014-9398-2.

Nguyen HT, Markides KS, Winkleby MA. Physician advice on exercise and diet in a US sample of obese Mexican-American adults. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25(6):402–9 https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.090918-QUAN-305.

Freburger JK, Carey TS, Holmes GM, Wallace AS, Castel LD, Darter JD, et al. Exercise prescription for chronic back or neck pain: who prescribes it? Who gets it? What is prescribed? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(2):192–200 https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24234.

Hayman M, Rebar P, Alley S, Cannon S, Short C. What exercise are women receiving from their healthcare practitioners during pregnancy? Women Birth. 2020;33(4):357–62 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.07.302.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Exercise is Medicine. RX for health series, a series on today's most common chronic conditions and their exercise prescriptions. https://www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/rx-for-health-series/. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(2):121–6 https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.116232.

Anderson RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137284.

Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med Care. 2008;46(7):647–53 https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The BRFSS user guide. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013.

Robertson R, Jepson R, Shepherd A, Mclnnes R. Recommendations by Queensland GPs to be more physically active: which patients were recommended which activities and what action they took. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2011;35(6):537–42 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00779.x.

Sinclair J, Lawson B, Burge F. Which patients receive advice on diet and exercise? Do certain characteristics affect whether they receive such advice? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(3):404–12.

Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Anderson's behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012;9:Doc11 https://doi.org/10.3205/psm000089.

Honda K. Factors underlying variation in receipt of physician advice on diet and exercise: applications of the behavioral model of health care utilization. Am J Health Promot. 2004;18(5):370–7 https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-18.5.370.

Stewart AL. The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35(4):295–309 https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6.

World Health Organization, International Association for the Study of Obesity & International Obesity Taskforce. The Asia Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Australia: Health Communications Australia Pty Limited; 2000.

Cantwell M, Walsh D, Furlong B, Moyna N, McCaffrey N, Boran L, et al. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practice of physical activity promotion in cancer care: challenges and solutions. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12795 https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12795.

Fisher A, Williams K, Beeken R, Wardle J. Recall of physical activity advice was associated with higher levels of physical activity in colorectal cancer patients. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006853 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006853.

Sreedhara M, Silfee VJ, Rosal MC, Waring ME, Lemon SC. Does provider advice to increase physical activity differ by activity level among US adults with cardiovascular disease risk factors? Fam Pract. 2018;35(4):420–5 https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmx140.

Croteau K, Schofield G, McLean G. Physical activity advice in the primary care setting: results of a population study in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30(3):262–7 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2006.tb00868.x.

Fontaine KR, Bartlett SJ, Heo M. Are health care professionals advising adults with arthritis to become more physically active? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(2):279–83 https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21073.

Ministry of Health New Zealand. Green Prescriptions. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/physical-activity/green-prescriptions. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

Patrick K, Pratt M, Sallis RE. The healthcare sector’s role in the U.S. national physical activity plan. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(Suppl 2):211–9 https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.6.s2.s211.

Zhu L, Wang ZZ, Zhu WM. Construction of exercise prescription database under the vision of healthy China. China Sport Sci. 2020;40(1):4–15.

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Exercise is Medicine survey: newsworthy analysis November 2007. Indianapolis: American College of Sports Medicine; 2007.

Eakin E, Brown W, Schofield G, Mummery K, Reeves M. General practitioner advice on physical activity--who gets it? Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(4):225–8 https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-21.4.225.

Zhu JC, Cui LL, Wang KH, Xie C, Sun N, Xu F, et al. Mortality pattern trends and disparities among Chinese from 2004 to 2016. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):780 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7163-9.

Wang MH, Xu S, Liu W, Zhang C, Zhang X, Wang L, et al. Prevalence and changes of BMI categories in China and related chronic diseases: cross-sectional National Health Service Surveys (NHSSs) from 2013 to 2018. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100521 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100521.

Muntner P, Gu DF, Wildman RP, Chen JC, Qan WQ, Whelton PK, et al. Prevalence of physical activity among Chinese adults: results from the international collaborative study of cardiovascular disease in Asia. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1631–6 https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.044743.

Austin S, Saag KG, Pisu M. Healthcare providers’ recommendations for physical activity among US arthritis population: a cross-sectional analysis by race/ethnicity. Arthritis. 2018;2018:2807035. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2807035–9.

Zhang S, Chen Q, Zhang B. Understanding healthcare utilization in China through the Andersen behavioral model: review of evidence from the China health and nutrition survey. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2019;12:209–24 https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S218661.

Carlson SA, Maynard LM, Fulton JE, Hootman JM, Yoon PW. Physical activity advice to manage chronic conditions for adults with arthritis or hypertension, 2007. Prev Med. 2009;49(2–3):209–12 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.017.

Manning VL, Hurley MV, Scott DL, Bearne LM. Are patients meeting the updated physical activity guidelines? Physical activity participation, recommendation, and preferences among inner-city adults with rheumatic diseases. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18(8):399–404 https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182779cb6.

Damush TM, Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Ritter PL. Prevalence and correlates of physician recommendations to exercise among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(8):M423–M7 https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/54.8.M423.

Hallal PC, Machado PT, Del Duca GF, Silva IC, Amorim TC, Borges TT, et al. Physical activity advice: short report from a population-based study in Brazil. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(3):352–4 https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.3.352.

Barbosa JMV, de Souza WV, Ferreira RWM, de Carvalho EMF, Cesse EAP, Fontbonne A. Correlates of physical activity counseling by health providers to patients with diabetes and hypertension attended by the family health strategy in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(4):327–36 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2017.04.001.

Whitaker KM, Baruth M, Schlaff RA, Talbot H, Connolly CP, Liu JH, et al. Provider advice on physical activity and nutrition in twin pregnancies: a cross-sectional electronic survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):418 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2574-2.

Bull FCL, Schipper ECC, Jamrozik K, Blanksby BA. How can and do Australian doctors promote physical activity? Prev Med. 1997;26(6):866–73 https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1997.0226.

Hebert ET, Caughy MO, Shuval K. Primary care providers’ perceptions of physical activity counselling in a clinical setting: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(9):625–31 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090734.

Weidinger KA, Lovegreen SL, Elliott MB, Hagood L, Haire-Joshu D, McGill JB, et al. How to make exercise counseling more effective: lessons from rural America. J Fam Pract. 2008;57(6):394–402.

Zhang C, Liu Y. The salary of physicians in Chinese public tertiary hospitals: a national cross-sectional and follow-up study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):661 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3461-7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and manuscript revision. SSCH conceptualized the study, supervised the whole study, and participated in data analysis, manuscript revision, proofreading and editing. EKPL and MS participated in manuscript revision, proofreading and editing. SYSW and YJY assisted in supervision of data collection, drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Reference number. SBRE-20-026). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This manuscript does not contain any data from any individual person.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Provision of Physical Activity Advice for Patients with Chronic Diseases. Additional file 1 is the questionnaire that we developed and used for data collection.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, R., Hui, S.Sc., Lee, E.Kp. et al. Provision of physical activity advice for patients with chronic diseases in Shenzhen, China. BMC Public Health 21, 2143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12185-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12185-7