Abstract

Background

The increasing number of cancer patients has an escalating economic impact to public health systems (approximately, International dollars- Int$ 60 billion annually in Brazil). Physical activity is widely recognized as one important modifiable risk factor for cancer. Herein, we estimated the economic costs of colon and post-menopausal breast cancers in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) attributable to lack of physical activity.

Methods

Population attributable fractions were calculated using prevalence data from 57,962 adults who answered a physical activity questionnaire in the Brazilian National Health Survey, and relative risks of colon and breast cancer from a meta-analysis. Annual costs (1 Int$ = 2.1 reais) with hospitalization, chemotherapy and radiotherapy were obtained from the Hospital and Ambulatory Information Systems of the Brazilian SUS. Two counterfactual scenarios were considered: theoretical minimum risk exposure level (≥8000 MET-min/week) and physical activity guidelines (≥600 MET-min/week).

Results

Annually, the Brazilian SUS expended Int$ 4.5 billion in direct costs related to cancer treatment, of which Int$ 553 million due to colon and breast cancers. Direct costs related to colon and breast cancers attributable to lack of physical activity were Int$ 23.4 million and Int$ 26.9 million, respectively. Achieving at least the physical activity guidelines would save Int$ 10.3 mi (colon, Int$ 6.4 mi; breast, Int$ 3.9 mi).

Conclusions

Lack of physical activity accounts for Int$ 50.3 million annually in direct costs related to colon and post-menopausal breast cancers. Population-wide interventions aiming to promote physical activity are needed to reduce the economic burden of cancer in Brazil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years in Brazil [1]. Breast and colorectal cancer are among the most common cancers, with an estimated combined number of 137,413 new cases and 42,924 deaths in 2018 [2]. By 2040, breast and colorectal cancers are expected to increase over 50% due to demographic and lifestyle changes [2]. Such an increase in the cancer burden may put further pressure on an already overwhelmed Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS), which covers more than 75% of the population [3, 4].

Physical activity is associated with lower risk of several types of cancer [5]. In 2018, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) concluded that strong evidence supports that physical activity reduces the risk of colon, breast and endometrial cancers [6]. Nonetheless, dose-response relationship has been well-characterized for colon and postmenopausal breast cancers only [7]. Of note, global estimates suggest that lack of physical activity causes 10% of all breast and colons cancers [8]. To reduce the risk of these cancers, as well as other non-communicable diseases, the 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for physical activity and sedentary behaviour calls for adults to do 150–300 min of moderate intensity, or 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or any equivalent combination of the itensities [9]. Despite the well-documented health benefits of reaching physical activity guidelines, global physical activity levels are not sufficient. In 2016, age-standardized prevalence of insufficient physical activity was 27.5%, with a higher prevalence in women (31.7%) than in men (23.4%) [10]. Latin America and Caribbean countries have showed the highest prevalence of insufficient physical activity (39.1%) worldwide, and Brazil presented the highest prevalence (47%) within the continent [10].

Insufficient physical activity cost health-care systems international dollars (Int$) 53.8 billion worldwide in 2013 [11]. Of note, these estimates were calculated considering direct health-care costs, productivity losses, and disability-adjusted life-years for coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, breast cancer, and colon cancer attributable to insufficient physical activity [11]. In Brazil, it has been estimated that approximately 10 thousand cancer cases and 3 thousand cancer deaths per year are attributable to insufficient physical activity [12]. However, to our knowledge, the economic costs of cancer in Brazil attributable to lack of physical activity are unknown, besides its potential to inform the financial impact of this exposure on the health system [13]. A cost-of-illness study include direct costs to health systems, patients and their families, and more broadly, the indirect costs to society (absenteeism, premature retirement and death). Nonetheless, data on indirect costs of cancer to society are unavailable in Brazil. On the other hand, a recent study estimated that approximately Int$ 7.54 billion were spent with oncological treatment by the Brazilian federal government from 2001 to 2015, of which Int$ 3.24 billion with breast cancer patients and Int$ 1.39 billion with colorrectal cancer patients [14].

In this study, we estimated the direct health care costs of colorectal and breast cancers in the Brazilian SUS attributable to lack of physical activity.

Methods

We designed a cost-of-illness study to estimate the direct costs of colorectal and breast cancers attributable to lack of physical activity from the perspective of the Brazilian SUS. This approach uses aggregated disease costs along with potential impact fraction (PIF) estimates to calculate the costs attributable to a given risk factor [13].

Direct health care costs of colorectal and breast cancers

Direct health care costs of all cancer (C00-C97), colorectal cancer (C18-C20), colon (C18), breast cancer (C50), and postmenopausal breast cancer (C50 for women 50 years or older) were obtained from the Brazilian SUS Ambulatory (Outpatient) Information System (SIA/SUS) [15] and the Hospital (Inpatient) Information System (SIH/SUS) [16] in 2017 (herein considered the average of 2015–2017) based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). SIH/SUS and SIA/SUS are publicly available and contain deidentified inpatient and outpatient care data. Direct health care costs were defined as those of outpatient and inpatient procedures. In our study, we included the following procedures and costs for patients aged 20 years or older:

Outpatient costs: chemotherapy (eg., conventional chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy and supportive therapy) and radiotherapy.

Inpatient costs: surgery and other hospital costs (eg., diagnostic and clinical procedures and organ, tissue and cell transplantation, including chemotherapy during hospitalization).

We converted the monetary values in Reais (R$) to Int$, considering the purchasing power parity (PPP) for 2015–2017 (conversion factor 2.10) [17].

Physical activity assessment

Physical activity was obtained from a national representative health survey conducted in Brazil in 2013, the National Health Survey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde – PNS 2013). Details about PNS methods have been reported elsewhere [12]. In this study, we included 57,962 adults aged 20 years or older that responded to a questionnaire about frequency and duration of recreational, occupational, commuting to work, commuting to other daily activities, and household activities in a typical week. We assigned metabolic equivalent of tasks (MET) for each activity and summed them to obtain total volume of physical activity (MET-min/week). MET were used to weight different types of aforementioned activities according to its intensity (meaning higher intensity having higher weight), as per the 2011 compendium of physical activities [18]. Details for these methods has been described elsewhere [12].

All PNS data are available on the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, IBGE) website at: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/pns/2013/default_microdados.shtm. The PNS was approved by Brazil’s National Research Ethics Committee (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa, CONEP) with the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde) Resolution No. 466/12 (No. 328159, June 26th, 2013), and all participants signed an informed consent at interview.

Data analysis: cost-of-illness modelling

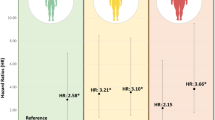

To estimate the direct health care costs of breast and colorectal cancers in the Brazilian SUS attributable to lack of physical activity, we first estimated PIF. Physical activity has been consistently associated with colon (C18) and postmenopausal breast cancer (C50 for women 50 years or older) [7]. Therefore, we first calculated PIF for colon by sex, and PIF for postmenopausal breast cancer for women using physical activity data from PNS 2013 and relative risks (RR) from published meta-analysis [7]:

Pi = proportion of the population at the level i of physical activity categories;

P’i = proportion of the population at the level i of physical activity categories in the counterfactual scenario. In this we considered two counterfactual scenarios: (1) Theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMRE): population reaching ≥8000 MET-min/week– aka population attributable fraction (PAF); (2) Physical activity guidelines (PA guidelines): population reaching at least 600 MET-min/week.

RRi is the relative risk of postmenopausal breast cancer and colon cancer at the level i of physical activity categories. These RR values are currently used in the Global Burden of Disease study [7].

Levels i of physical activity were < 600, 600 to 3999, 4000 to 7999, and ≥ 8000 MET-min/week (reference group), same in the aforementioned dose-response meta-analysis [7].

PIFs were applied to procedures and costs of hospitalizations, chemotherapy and radiotherapy of colon cancer and postmenopausal breast cancer to calculate the costs attributable to lack of physical activity. Then, we divided colon cancer (C18) and postmenopausal breast cancer (C50 for women 50 years or older) costs attributable to lack of physical activity by total colorectal (C18-C20) and breast cancer (C50) costs, respectively. Data analysis were performed in Stata 15.0 and Microsoft Excel Office® 2007 spreadsheets.

Results

Table 1 displays the costs of hospitalization, chemotherapy and radiotherapy by cancer site and sex in Brazil in 2017. Approximately Int$ 4.5 billion was spent on direct health care related to all cancer types, of which 12.4% or Int$ 553 million were due to colorectal cancer (Int$ 212 million) and breast cancer (Int$ 341 million). For colorectal cancer, Int$ 121 million were spent on chemotherapy, Int$ 82 million on hospitalization, and Int$ 8 million on radiotherapy. Colorectal cancer costs were similar for men (Int$ 105 million) and women (Int$ 106 million). For breast cancer, Int$ 231 million were spent on chemotherapy, Int$ 62 million on hospitalization, and Int$ 48 million on radiotherapy.

Direct costs with colon cancer (Int$ 134 million) represented 63% of all colorectal cancer costs (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Considering the TMRE scenario, about Int$ 23 million of colon cancer costs were attributable to lack of physical activity, which represented 11% of all colorectal cancer costs. Attributable costs with colon cancer (Table 2) were slightly higher in women (Int$ 12 million) than in men (Int$ 10 million). Most of the attributable costs were due to chemotherapy (Int$ 15 million), followed by hospitalization (Int$ 8 million) and radiotherapy (Int$ 48 thousand). In the PA guidelines scenario, we estimated that Int$ 6 million could be potentially saved annually by increasing population-wide physical activity level to ≥600 MET-min/week, of which Int$ 4 million on chemotherapy, Int$ 2 million on hospitalizations and Int$ 13 thousand on radiotherapy.

Direct costs with postmenopausal breast cancer (Int$ 226 million) represented 66% of all breast cancer costs (Table 3). We estimated that Int$ 26.9 million of postmenopausal breast cancer costs were attributable to lack of physical activity, which represents 12% of the postmenopausal breast cancer costs and 5.6% of all breast cancer costs. Breast cancer attributable costs were distributed as follows: Int$ 18.5 million for chemotherapy, Int$ 4.7 million for hospitalization, and Int$ 3.7 million for radiotherapy. About Int$ 4 million could be potentially saved annually by reaching PA guidelines, of which Int$ 2.6 million on chemotherapy, Int$ 676 thousand on hospitalizations and Int$ 539 thousand on radiotherapy.

Combined costs of breast and colon cancer attributable to lack of physical activity was Int$ 50.3 million, of which Int$ 33.9 million were due to chemotherapy, Int$ 12.6 million to hospitalizations, and Int$ 3.8 million to radiotherapy. PA guidelines scenario would result in Int$ 10.3 million saved annually, of which Int$ 6.9 million were due to chemotherapy, Int$ 2.8 million to hospitalizations, and Int$ 552 thousand to radiotherapy.

Discussion

In this study, we estimated the direct costs of colorectal and breast cancers in the Brazilian SUS attributable to lack of physical activity. We found that Int$ 26.9 million of postmenopausal breast cancer and Int$ 23.4 million of colon cancer costs were attributable to lack of physical activity in Brazil in 2017. Considering a plausible counterfactual scenario of reaching at least the physical activity guidelines would result in Int$ 10.3 million saved annually.

Cancer has an enormous societal cost. The increasing number of cancer patients has an escalating economic impact to public health systems and society. In 2016, it has been estimated that the cost of cancer to the Brazilian public and private health system was around Int$ 60 billion, which represented around 1.7% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product per year. Direct costs with inpatients and outpatients represent around 20% of all costs [19]. Our study showed that Int$ 553 million (12%) out of the Int$ 4.5 billion spent with direct health care related to all cancer in the Brazilian SUS were due to colorectal cancer (Int$ 212 million) and breast cancer (Int$ 341 million). Part of these costs could be saved or reallocated with investments in primary prevention strategies.

Quantifying the burden of cancer, in terms of cases, deaths and costs, attributable to modifiable risk factors can help policymakers to understand the importance of prioritizing primary prevention strategies. In Brazil, it has been estimated that about 27% of all cancer cases and 34% of all cancer deaths could be averted by reducing the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, overweight and obesity and lack of physical activity [20]. Annually, about 10 thousand cancer cases (3878 colon and 6712 breast) and 3226 cancer deaths (1444 colon and 1782 breast) could be potentially avoided by promoting physical activity [20]. Our study adds information to these previous estimates by quantifying the economic burden of breast and colorectal cancer attributable to lack of physical activity.

The relationship between physical activity and cancer have received great attention and sharply increased in the past few years [5]. Traditionally, physical activity has been associated with reduced risk of colon and breast cancer in postmenopausal women, as illustrated in the estimates from the Global Burden of Disease study [21]. However, more recently, large pooled data studies including over 1 million participants have suggested that physical activity may additionally reduce the risk of other types of cancer such as bladder, breast, endometrial, esophageal, stomach, glioma, kidney, lung, ovarian, pancreas and prostate [22]. Although the 2018 WCRF report considers convincing/probable the evidence for inverse association of physical activity with breast, colon and endometrial only [6], the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recently considered strong the evidence for inverse association between physical activity and seven types of cancer: bladder, breast, colon, endometrial, esophageal, pancreas and stomach [23]. Due to these divergences in the literature, we decided to estimate the cost of breast and colorectal cancer, which are the most well-established, with available estimates of dose-response relationship with total physical activity [7].

To our knowledge, there have a few country-wide studies on the economic burden of cancer due to lack of physical activity [11, 24,25,26]. In the United Kingdom (UK), insufficient physical activity was responsible for £1.06 billion to the National Health Service in 2002, with breast and colon/rectum cancers contributing to £240 and £383 million, respectively [24]. Of note, the UK study included rectal cancers (C20) in their estimates, although there is limited evidence supporting that physical activity reduces this type of cancer [6]. A recent study conducted in the Sweden suggested that insufficient physical activity was responsible for 0.91% (1.7 billion Swedish Krona) of total health care costs in 2016, of which 575 million Swedish Krona were spent with health care utilization, mortality and early retirement due to breast and colon cancer [25]. Finally, in the United States of America, $0.38 billion were spent on direct costs of breast and $2.0 billion on colon cancers in 1995 due to lack of physical activity [26]. Although all studies were conducted in high-income countries, comparing cancer cost estimates from these studies is challenging due to its different methods, currencies, health care systems and year of reference.

The most comprehensive study estimated that insufficient physical activity cost health care systems Int$ 53.8 billion worldwide in 2013, of which Int$ 2.7 billion were spent on breast cancer and Int$ 2.5 billion on colon cancer [11]. Estimated direct health care costs for breast and colon cancer varied widely across the globe, from Int$ 16.7 million in African countries (breast, Int$ 8.8 million; colon, Int$ 7.9 million) to Int$ 5.2 billion (breast, Int$ 2.7 billion; colon, Int$ 2.5 billion) in the Western Pacific. In Brazil, direct health care costs for breast and colon cancer were Int$ 38.3 million and Int$ 36.4 million, respectively [11]. Our study provided similar, but more conservative estimates for the direct health care costs for breast and colon cancers. These differences might due to differences in data sources used to calculate PIF/PAF estimates, as well as health care costs. Of note, our study adds information providing direct costs due to hospitalizations, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. In addition, we provided results for two alternative counterfactual scenarios (TMRE and physical activity guidelines).

Our study has several limitations. First, we considered only direct health care costs related to colorectal and breast cancers, which did not consider indirect costs (eg. premature mortality, loss of productivity and quality of life) and out-of-pocket expenditures. Physical activity may also reduce the risk of other types of cancer not included in our analysis [22]. Therefore, our findings should not be interpreted as the total costs of cancer attributable to lack of physical activity. Second, validated [27] but self-reported physical activity dates from 2013, when the most recent national representative health survey was conducted in Brazil. This may have introduced misclassification bias due to errors inherent to questionnaires and changes in physical activity over time. Third, we used RR estimates derived from a dose-response meta-analysis including studies mainly from US and Europe [7]. Transportability of RR, and therefore PIF/PAF estimates, may be biased if the prevalence of potential effect modifiers in these settings differs from Brazil [28]. Finally, SUS database gives only information on the total amount reimbursed by the federal government to the country’s health services, which did not consider other modalities of states’ and municipalities’ expenditures. Our cost estimates attributable to lack physical activity did not consider other non-communicable diseases previously linked with physical activity.

Conclusions

Quantifying the economic burden of cancer in the public health system attributable to modifiable risk factors can help policymakers to understand and value the importance of primary prevention strategies. Our study provides evidence on the breast and colorectal cancers expenditures attributable to lack of physical activity in the Brazilian SUS. Annually, around Int$ 50.4 million of direct colorectal and breast cancers costs are attributable to lack of physical activity, which represents a substantial economic burden for the Brazilian health system. Primary prevention strategies aiming to promote physical activity, alongside with other health behaviors, are imperative to reduce the economic burden of cancer.

Availability of data and materials

All PNS data are available on the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, IBGE) website at: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/pns/2013/default_microdados.shtm.

Abbreviations

- ACSM:

-

American College of Sports Medicine

- iInt$:

-

International dollars

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent of tasks

- Mi:

-

Million

- PAF:

-

Population attributable fraction

- PIF:

-

Potential impact fractions

- PPP:

-

Purchasing power parity

- R$:

-

Reais

- RR:

-

Relative risks

- PNS:

-

National Health Survey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde)

- SUS:

-

Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde)

- TMRE:

-

Theoretical minimum risk exposure level

- WCRF:

-

World Cancer Research Fund

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. Published 2018. Accessed 25 May 2020.

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today. Published 2018. Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

Massuda A, Hone T, Leles FAG, de Castro MC, Atun R. The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis and resilience. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(4):e000829. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000829.

Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1778–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8.

Rezende LFM, Sa TH, Markozannes G, Rey-Lopez JP, Lee IM, Tsilidis KK, et al. Physical activity and cancer: an umbrella review of the literature including 22 major anatomical sites and 770 000 cancer cases. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(13):826–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098391.

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Physical activity and the risk of cancer. Available at dietandcancerreport.org

Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford JE, Afshin A, Estep K, et al. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. BMJ. 2016;354:i3857.

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Lancet physical activity series working G: effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9.

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1077–86.

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, van Mechelen W, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1311–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X.

Rezende LFM, Garcia LMT, Mielke GI, Lee DH, Wu K, Giovannucci E, et al. Preventable fractions of colon and breast cancers by increasing physical activity in Brazil: perspectives from plausible counterfactual scenarios. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;56:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2018.07.006.

Jo C. Cost-of-illness studies: concepts, scopes, and methods. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20(4):327–37. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2014.20.4.327.

Lana AP, Perelman J, Gurgel Andrade EI, Acurcio F, Guerra AA Jr, Cherchiglia ML. Cost analysis of Cancer in Brazil: a population-based study of patients treated by public health system from 2001-2015. Value Health Reg Issues. 2020;23:137–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2020.05.008.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. SIASUS- Sistema de Informações ambulatoriais do SUS. http://datasus.saude.gov.br/sistemas-e-aplicativos/ambulatoriais/sia. Published 2017. Accessed 25 Oct 2018.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. SIHSUS- Sistema de Informações Hospitalares do SUS. http://datasus.saude.gov.br/sistemas-e-aplicativos/hospitalares/sihsus. Published 2018. Accessed 25 Oct 2016.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Purchasing power parities (PPP) (indicator). Total, National currency units/US dollar, 2000–2019. doi:doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/1290ee5a-en. In.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–81. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12.

Siqueira A, Goncalves J, Xavier de Mendonça P, Merhy E, Land MGP. Economic impact analysis of cancer in the health system of Brazil: model based in public database. Heal Sci J. 2017;11(4):514.

Rezende LFM, Lee DH, Louzada M, Song M, Giovannucci E, Eluf-Neto J. Proportion of cancer cases and deaths attributable to lifestyle risk factors in Brazil. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;59:148–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2019.01.021.

Collaborators GBDRF. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1923–94.

Moore SC, Lee IM, Weiderpass E, Campbell PT, Sampson JN, Kitahara CM, et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity with Risk of 26 types of Cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):816–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548.

Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and Cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2391–402. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002117.

Allender S, Foster C, Scarborough P, Rayner M. The burden of physical activity-related ill health in the UK. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(4):344–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.050807.

Bolin K. Physical inactivity: productivity losses and healthcare costs 2002 and 2016 in Sweden. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000451.

Colditz GA. Economic costs of obesity and inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11 Suppl):S663–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199911001-00026.

Moreira AD, Claro RM, Felisbino-Mendes MS, Velasquez-Melendez G. Validity and reliability of a telephone survey of physical activity in Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2017;20(1):136–46. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5497201700010012.

Rezende LF, Eluf-Neto J. Population attributable fraction: planning of diseases prevention actions in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2016;50(0). https://doi.org/10.1590/S1518-8787.2016050006269.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant 2018/23941–9. Brazilian National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), no. 442658/2019–2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LFMR designed the study and selected the study methodology. LFMR performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. LFMR and GF analyzed and interpreted the data. LRB, RDSR, MQMR, RCS, DHL, EG, JE-N edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The PNS was approved by Brazil’s National Research Ethics Committee (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa, CONEP) with the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde) Resolution No. 466/12 (No. 328159, June 26th, 2013), and all participants signed a free and informed consent at interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezende, L.F.M., Ferrari, G., Bahia, L.R. et al. Economic burden of colorectal and breast cancers attributable to lack of physical activity in Brazil. BMC Public Health 21, 1190 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11221-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11221-w