Abstract

Background

We updated the indirect estimates for women and girls living with Female Genital Mutilation Cutting (FGM/C) in Switzerland, using data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office of migrant women and girls born in one of the 30 high-prevalence FGM/C countries that are currently living in Switzerland.

Methods

We used Yoder and Van Baelen’s “Extrapolation of FGM/C Countries’ Prevalence Data” method, where we applied DHS and MICS prevalence figures from the 30 countries where FGM/C is practiced, and applied them to the immigrant women and girls living in Switzerland from the same 30 countries.

Results

In 2010, the estimated number of women and girls living with or at risk of FGM/C in Switzerland was 9059, whereas in 2018, we estimated that 21,706 women and girls were living with or at risk of FGM/C.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, there have been significant increases in the number of estimated women and girls living with or at risk of FGM/C in Switzerland due to the increase in the total number of women and girls originally coming form the countries where the practice of FGM/C is traditional.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The practice of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) has been recorded in more than 31 countries around the world. The prevalence of the traditional practice has been widely documented, with standardized survey methodologies developed and refined over the past decades. The main surveys used to estimate prevalence of FGM/C are the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) developed by ICF International [1] and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) led by UNICEF [2]. These surveys provide national FGM/C estimates by sampling households that are representative of the national population and asking them a series of questions about FGM/C, such as whether and how the procedure was conducted, at what age, and by type of practitioner.

UNICEF’s most recent estimates report that the number of women and girls that have undergone FGM/C globally have reached 200 million [3]. However, their estimates lack data from countries where the traditional practice is carried out but no data exists (e.g. Saudi Arabia, India, etc.). Additionally, this estimate does not include data from high-income countries where first or following generations of women and girls with FGM/C live [4]. The real prevalence and incidence of FGM/C is unknown in Switzerland and many parts of Europe, as there are no representative surveys similar to DHS or MICS for European countries. Demographers predict that migrants coming from FGM/C-practicing countries towards high income and European countries such as Switzerland will continue to increase [5]. A study published in 2016 analyzing data from the 2011 European census, estimated that, of the 1,353,970 women and girls in Europe aged 10 years and above coming from 1 of the 30 high-prevalence FGM/C countries, an estimated 578,068 women and girls have undergone some type of FGM/C [4]. As of February 2020, there are now 31 FGM/C high-prevalence countries with MICS/DHS estimates, with the addition of the Maldives. The surge of migrants from these countries thus affects the number of women and girls living with FGM/C in Europe. In 2016, estimates in Switzerland showed that around 14,700 women and girls were respectively living with FGM/C or were considered to be theoretically at risk of having undergone or undergoing FGM/C in the future due to their geographical origin only [6]. Since then, estimates have not been updated.

Maria Roth Bernasconi’s parliament initiative to introduce a specific Swiss penal code article against female genital mutilation was the catalyst for the Swiss government’s involvement in the issue of FGM/C [7]. The Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) has been funding awareness-raising and prevention measures aimed at preventing FGM/C through the national program Migration and Health since 2003. The State Secretariat for Migration, SEM, has been involved in these activities since 2010 as well. In 2015, the National Council decided to support a network to tackle female genital mutilation for the 2016–2019 period. This period has been prolonged until 2021 [8].

More recent and regular estimates on women and girls affected by FGM/C need to be carried out in Switzerland to guide policies. One of the biggest challenges to getting up-to-date estimates is to determine a reliable number of migrant women and girls by country of origin, which usually requires access to census data of the country—limiting estimates to ten-year periods for many European countries. Switzerland is in a unique position because since 2010, the Swiss census is carried out annually, providing a modern statistical database for researchers, policy makers, etc. to observe various data points on a continuous basis [9].

The aim of this study is to update the indirect prevalence estimates for women and girls living with FGM/C in Switzerland, using data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office of migrant women and girls, born in one of the 30 high-prevalence FGM/C countries that are currently living in Switzerland, i.e. first-generation migrants. Such an update is the first step of a wider research project conducted in Switzerland in 2018 entitled “Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting with a focus on prevalence, risk factors and Swiss health care professionals’ capacities”.

Methods

We used a similar methodology to Yoder and Van Baelen [4, 10], applying FGM/C DHS and MICS prevalence figures (for girls and women age 15–49) from high-prevalence countries to the number of migrant women and girls living in Switzerland.

We applied the total country prevalence estimates of women aged 15–49 to all migrant women and girls living in Switzerland from the same countries. We also conducted a separate analysis for girls aged 0–14, where we applied the prevalence estimates of girls 0–14 to all migrant girls 0–14 living in Switzerland from the same countries. Where no prevalence estimates for girls 0–14 were available, we applied the prevalence estimates for girls 15–19.

We used the most recent MICS or DHS estimates available for each year (Table 1) and multiplied them to the number of immigrant women and girls from each FGM/C high-prevalence country from 2010 to 2018 based on the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO)‘s Interactive Database. USAID’s Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) are large-scale population-based surveys that produce estimates of socioeconomic and health indicators in low- and middle-income countries [1, 2]. The DHS and MICS surveys have played an important role in the reporting of FGM/C prevalence data in low- and middle- income countries over the past 30 years. Table 1 shows the prevalence estimates from women and girls aged 15–49 that are available for 30 countries where FGM/C is practiced that we used in our study.

We used the Swiss Federal Statistical Office’s (FSO) publicly available interactive database STAT-TAB to obtain the number of female permanent and non-permanent residents living in Switzerland from 2010 to 2018 from high FGM/C prevalence countries [11].

We included women and girls of all ages, who have a residence permit labeled “Swiss”, Residence permit (permit B), a settlement permit (permit C), a residence permit with gainful employment (permit Ci), a status of provisionally admitted person (permit F), or of asylum seeker (permit N), or who were diplomats, international civil servants with diplomatic immunity and international civil servants without diplomatic immunity. The citizenship countries that we included were the ones for which FGM/C estimates were available and is known to be practiced: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Iraq, Yemen (Table 2) [3]. Table 2 shows the number of migrant women and girls of all ages living in Switzerland from high FGM/C prevalence countries between 2010-2018. This differs slightly from the UNICEF Switzerland estimates from 2012, as Zambia has since been excluded, and Iraq has been included [12].

Table 3 shows the number of migrant girls aged 0–14 living in Switzerland from 2010 to 2018 from high FGM/C prevalence countries. We used the STAT-TAB database to obtain the information.

Results

Table 4 describes the estimated total number of women and girls in Switzerland that are living with FGM/C. Indonesia was excluded because there are no DHS and MICS prevalence estimates for the country. In 2010, there were 914 women and girls from Indonesia living in Switzerland, and in 2018, there were 1229.

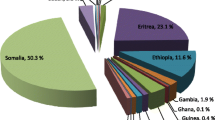

The evolution of migratory flows throughout the past years has had an effect on the total number of female migrants from these high-prevalence FGM/C countries (Table 2). Between 2010 and 2018, the total number of female migrants has increased, particularly from Eritrea (5-fold increase), with smaller increases from Ethiopia, Egypt, Gambia, Iraq, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, and Sudan & South Sudan. The number of women from Chad, Sierra Leone and Liberia has slightly declined, while others have stayed stable. Thus, the number of girls and women affected by FGM/C has changed as well.

Over the past decade, there have been significant increases in the number of estimated women and girls living with FGM/C in Switzerland. Our estimates show that in 2010, of the 19,506 women and girls living in Switzerland coming from 1 of the 30 countries where FGM/C is traditional, an estimated 9059 were subjected to the harmful practice. In 2018, of the 36,898 women and girls living in Switzerland coming from 1 of the 30 high prevalence FGM/C countries, an estimated 21,706 have been subjected to the harmful practice.

More than 16,000 of the 36,898 migrant women from the FGM/C high prevalence countries in 2018 come from Eritrea. The indirect estimation of Eritrean women living in Switzerland, where FGM/C estimated prevalence is among the highest in the world, is 13,730. The second highest migrant group of this population comes from Somalia, where the FGM/C estimated prevalence is almost 98%. Out of 3290 women and girls living in Switzerland from Somalia, the applied indirect estimate is 3220 women.

Some countries have made improvements to their prevalence rates over the past years, for example Ethiopia, whose prevalence was .742 in 2010 and has decreased to .650 in 2016, which has an impact on the number of women and girls originating from these countries estimated to be living with FGM/C in Switzerland. In 2010, out of 1495 women and girls from Ethiopia, 1110 were estimated to be living with FGM/C. Fast forward to 2018, 1365 women and girls are estimated to be living with FGM/C out of 2095 total migrant women from Ethiopia.

Table 5 describes the estimated total number of girls ages 0–14 in Switzerland that are at risk of or have undergone FGM/C. This number is based on the indirect prevalence calculation, using data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office of migrant girls born in one of the 30 high-prevalence FGM/C countries that are currently living in Switzerland (Tables 3 and 4), and multiplied by each country’s most recent DHS and MICS prevalence estimates for ages 0–14. Where estimates for this age group were not available, estimates for the 15–19 age group were used. In 2018, of the 11,022 girls living in Switzerland coming from 1 of the 30 high prevalence FGM/C countries, 3512 are estimated to be at risk or have been subjected to the harmful practice. Migrant girls from countries such as Eritrea, Gambia, Guinea, Senegal and Somalia all saw increases in the number of girls aged 0–14 that are estimated to be living with or at risk of FGM/C in Switzerland between 2010 and 2018. Over the past 10 years, some countries saw a decrease in the number of girls aged 0–14 that are estimated to be living with FGM/C in Switzerland, such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, and Yemen,

The applied indirect estimates for 2018 show a significant decrease for the number of migrant girls with FGM/C from Iraq. New prevalence estimates reported that .005% of girls in Iraq are reported to be at risk or have undergone any form of FGM/C. Out of 1253 girls from Iraq, only 6 girls are estimated to be at risk or have undergone FGM/C. All tables and estimations are available in Additional file 1.

Discussion

The increase in overall migration from the 30 high-prevalence FGM/C countries should not be overlooked. This increased migrant population leads to an increased estimated FGM/C indirect prevalence [11]. Take for example, the large number of Eritreans present in Switzerland. In 2017, 18,088 people sought asylum in Switzerland [13]. The main country of origin of asylum seekers was Eritrea, with 3375 applications, accounting for over 10% of all applications [13]. Eritreans have been fleeing compulsory military service and dictatorship in their country [14]. However, these asylum applications have continued to fall the past couple of years both in Europe and Switzerland [13]. In 2017, asylum applications were down 33% from 2016—one of the main reasons being that Eritrean arrivals had significantly fallen and that had a direct impact on the number of asylum applications.

Indirect estimation is a systematic and affordable method for estimating the number of women with FGM/C in high-income countries [15,16,17]. Leye et al. outline that these estimations allow policy makers to look for trends as well as evaluate the impact of prevention programs based on reliable approximations [18]. However, it has methodological limitations and may not reflect the actual FGM/C prevalence among migrants in Switzerland or any community.

There are several demographic characteristics that can influence a woman or girl’s likelihood of having undergone FGM/C that are not taken into account when making indirect estimates. The migrant population in Switzerland may or may not be representative of the population in their country of origin due to socio-economic status, regional origin, religion or ethnicity and therefore may not accurately emulate the prevalence of FGM/C in their home country [19]. For example, we cannot accurately rely on indirect measures for migrants from countries where FGM/C prevalence differs greatly according to ethnicity, without taking into account the migrant’s ethnicity, which is often not included in demographic or census data [20, 21].

Indirect estimates do not account for factors that may influence migrant’s change of behavior, attitudes and beliefs towards FGM/C such as laws prohibiting the practice of FGM/C as well as social pressure not to carry out the traditional practice. However, laws do not always explain the diminishing trend of FGM/C, as similar trends are observed in countries with and without legislation forbidding the practice [22]. The longer migrants stay in Switzerland, the more acculturation is likely to occur, which could lead either to the abandonment of the practice, or to the preservation of the tradition [23].

Prevalence estimations do not account for the many women and girls that are unaware if they underwent the cutting or of the type of FGM/C they may be living with because there is no physical examination of the genitalia, and therefore the estimations of the prevalence in their country of origin may be underreported [24]. Because of that, surveying samples of migrants might inform future estimates and inform interventions, but would also have limitations.

The real prevalence and incidence of FGM/C and the number of minors at risk remain unknown in many countries, including Switzerland. Our estimates look at major age groupings of girls 0–14 and women over 15. We did not take into account age-adjusted groupings by 5-year groups. Additionally, prevalence estimates that would look at both the Swiss region and canton would allow us to implement more targeted interventions. To obtain more accurate indirect estimates, more detailed information on migrant’s ethnicity as well as their region of origin would need to be recorded upon entry into Switzerland, as FGM/C prevalence often varies significantly in certain ethnic groups and regions.

Despite the various limitations to using indirect measures, we can nevertheless show that there has been a significant increase in the number of women and girls living with or at risk of FGM/C in Switzerland since the previous estimates were conducted. Although we must improve our future estimates, our data show that we must also improve the Swiss capacity for FGM/C monitoring, prevention, treatment and training on this population across diverse settings (medical, social, school, asylum, police).

Conclusion

Our indirect estimates can only partially inform future policy and public health programs. We believe that indirect estimates should be conducted alongside direct estimates. Direct measures may provide more accurate estimates that could guide policy- and clinical decision-making. Surveying samples of migrants to estimate FGM/C prevalence also has limitations, as they might not know whether they experienced FGM/C or be unaware of the type. However, the implementation of questions about history and type of FGM/C could be integrated into routine health examinations for women and girls coming from countries at risk upon entry into Switzerland, as long as the necessary training is provided. We recommend healthcare professionals and medical coders to use our proposed list of codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to document and code FGM/C, its associated procedures, and complications, as well as girls “at risk” [25]. Because the ICD is already used by countries around the world, our proposed methods would be feasible in many countries with the proper training on how to diagnose, classify and document FGM/C correctly. ICD is an existing tool that allows for standardized international comparisons [25]. Additionally, we hypothesize that accurate documentation and coding of FGM/C by care-givers will provide more reliable data than those obtained through self-reporting. Furthermore, hospital data represents an opportunity to study access and quality of care for patients who underwent FGM/C, providing guidance for health interventions.

These estimates are meant to be compared with direct data obtained from Swiss University Hospitals in the next steps of a wider research project conducted in Switzerland in 2018 entitled “Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting with a focus on prevalence, risk factors and Swiss health care professionals’ capacities. As a follow-up to these estimates, we conducted a study to assess the coded diagnoses of FGM/C in the five Swiss University Hospitals (paper under review).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Swiss Statistical Office’ interactive database, STAT-TAB available at: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/services/recherche/stat-tab-online-data-search.html

The DHS and MICS data used in this paper are publicly available on the respective websites (www.dhsprogram.com; www.mics.unicef.org/surveys).

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- FGM/C:

-

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

- MICS:

-

Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey

References

DHS. The DHS Program. Demographic and Health survey. 2019. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/.

Unicef. Statistics and Monitoring. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS). 2014. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/statistics/index_24302.html.

UNICEF. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: a global concern New York: Unicef; 2016. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGMC_2016_brochure_final_UNICEF_SPREAD(2).pdf.

Van Baelen L, Ortensi L, Leye E. Estimates of first-generation women and girls with female genital mutilation in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21(6):474–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2016.1234597.

UNICEF. Female genital mutilations/cutting: what might the future hold? New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2014.

Confederation Suisse. Measures against female genital mutilation 2018. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/gesundheitliche-chancengleichheit/chancengleichheit-in-der-gesundheitsversorgung/massnahmen-gegen-weibliche-genitalverstuemmelung.html.

Le Parlament suisse. Réprimer explicitement les mutilations sexuelles commises en Suisse et commises à l'étranger par quiconque se trouve en Suisse Berne. 2005 Available from: https://www.parlament.ch/fr/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20050404.

Swiss Network against female circumcision. 2016. Available from: https://www.excision.ch/.

Federal Office of Public Health. Census: Swiss Confederation; 2017. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/surveys/volkszaehlung.html.

Yoder PS, Wang S, Johansen E. Estimates of female genital mutilation/cutting in 27 African countries and Yemen. Stud Fam Plan. 2013;44(2):189–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00352.x.

Confederation Suisse. STAT-TAB-interactive tables (FSO) 2019. Available from: https://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/en/px-x-0103010000_101/px-x-0103010000_101/px-x-0103010000_101.px/?rxid=d703f21a-7125-40e7-9c1a-4c7d66d1812e.

Schweiz U. Weibliche Genitalverstümmelung in der Schweiz. Umfrage 2012 – Risiko, Vorkommen, Handlungsempfehlungen. Zürich: UNICEF Schweiz; 2013.

Confederation Suisse. Migration report 2017. State Secretariat for Migration SEM, FDJP FDoJaP; 2018.

Human Rights Watch. Country Summary: Eritrea 2018. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/eritrea_3.pdf.

Ortensi LE, Farina P, Leye E. Female genital mutilation/cutting in Italy: an enhanced estimation for first generation migrant women based on 2016 survey data. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-5000-6.

Now E. Female genital mutilation: report of a research methodological workshop on estimating the prevalence of FGM in England and Wales. London: Equality Now; 2012.

De Schrijver L, Van Baelen L, Van Eekert N, Leye E. Towards a better estimation of prevalence of female genital mutilation in the European Union: a situation analysis. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):105.

Leye EDSL, Van Baelen L, Andro A, Lesclingand M, Ortensi L, Farina P. Estimating FGM prevalence in Europe: findings of a pilot study. Ghent: Ghent University; 2017.

Ortensi LE, Farina P, Menonna A. Improving estimates of the prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting among migrants in Western countries. Demogr Res. 2015;32(18):543–62. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.18.

Ziyada MM, Norberg-Schulz M, Johansen REB. Estimating the magnitude of female genital mutilation/cutting in Norway: an extrapolation model. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):110.

Kawous R, van den Muijsenbergh METC, Geraci D, van der Kwaak A, Leye E, Middelburg A, et al. The prevalence and risk of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting among migrant women and girls in the Netherlands: An extrapolation method. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230919–e.

Cetorelli V, Wilson B, Batyra E, Coast E. Female genital mutilation/cutting in Mali and Mauritania: understanding trends and evaluating policies. Stud Fam Plan. 2020;51(1):51–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12112.

Wahlberg A, Johnsdotter S, Ekholm Selling K, Essen B. Shifting perceptions of female genital cutting in a Swedish migration context. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0225629. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225629.

Elmusharaf S, Elhadi N, Almroth L. Reliability of self reported form of female genital mutilation and WHO classification: cross sectional study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2006;333(7559):124.

Cottler‐Casanova S, Horowicz M, Gieszl S, Johnson‐Agbakwu C, Abdulcadir J. Coding female genital mutilation/cutting and its complications using the International Classification of Diseases: a commentary. BJOG. 2020;127:660–4.

Acknowledgements

Nasteha Salah for her feedback and comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, the Swiss Network Against Female Circumcision and Caritas Switzerland. The funding bodies had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SCC- Conceptualization, Data collection, Data Analyses, Interpretation, Discussion of Findings, Review of Literature. JA-Conceptualization, Interpretation, Discussion of Findings, Review of Literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethics approval and consent to participate was required to access the relevant data.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable. Data was fully anonymized.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

This is the full excel file of all FGM/C indirect estimates from 2010 to 2018 for women and girls living in Switzerland.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cottler-Casanova, S., Abdulcadir, J. Estimating the indirect prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting in Switzerland. BMC Public Health 21, 1011 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10875-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10875-w