Abstract

Background

With the growing epidemic of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) in sub-Saharan Africa, behavioural change interventions are critical in supporting populations to achieve better cardiovascular health. Population knowledge regarding CVD is an important first step for any such interventions. This study examined CVD prevention knowledge and associated factors among adults in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda.

Methods

The study was cross-sectional in design conducted among adults aged 25 to 70 years as part of the baseline assessment by the Scaling-up Packages of Interventions for Cardiovascular disease prevention in selected sites in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa (SPICES) – project. Data were collected using pretested semi-structured questionnaires, and respondents categorized as knowledgeable if they scored at least five out of six in the knowledge questions. Data were exported into STATA version 15.0 statistical software for analysis conducted using mixed-effects Poisson regression with fixed and random effects and robust standard errors.

Results

Among the 4372 study respondents, only 776 (17.7%) were knowledgeable on CVD prevention. Most respondents were knowledgeable about foods high in calories 2981 (68.2%), 2892 (66.1%) low fruit and vegetable intake and high salt consumption 2752 (62.9%) as CVD risk factors. However, majority 3325 (76.1%) thought the recommended weekly moderate physical activity was 30 min and half 2262 (51.7%) disagreed or did not know that it was possible to have hypertension without any symptoms. Factors associated with high CVD knowledge were: post-primary education [APR = 1.55 (95% CI: 1.18–2.02), p = 0.002], formal employment [APR = 1.69 (95% CI: 1.40–2.06), p < 0.001] and high socio-economic index [APR = 1.35 (95% CI: 1.09–1.67), p = 0.004]. Other factors were: household ownership of a mobile phone [APR = 1.35 (95% CI: 1.07–1.70), p = 0.012] and ever receiving advice on healthy lifestyles [APR = 1.38 (95% CI: 1.15–1.67), p = 0.001].

Conclusions

This study found very low CVD knowledge with major gaps around recommended physical activity duration, diet and whether hypertension is asymptomatic. Observed knowledge gaps should inform suitable interventions and strategies to equip and empower communities with sufficient information for CVD prevention.

Trial registration

ISRCTN Registry ISRCTN15848572, January 2019, retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), many countries are facing an epidemic of non-communicable diseases contributing to morbidity, mortality, and loss of productivity and economic growth [1,2,3]. Among the non-communicable conditions, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death and disability contributing over 1 million deaths in 2013, 5.5% of all global deaths that year [1]. The growing burden of CVD in SSA, expected to double by 2030, is attributed to population growth, aging and changing lifestyles regarding physical activity, diets, alcohol consumption and tobacco use [1, 3]. In Uganda, the prevalence of physiological risk factors such as hypertension [4] and other determinants including alcohol consumption, unhealthy diets and overweight are high and rising [4, 5]. In Mukono and Buikwe districts, among persons aged above 15 years and above, 21.8% have high blood pressure but with low levels of status awareness and control [6], much like the rest of the country [4].

To deal with the rising burden of CVD in SSA, innovative behavioural change interventions are warranted to address the rising risk factors and support populations to achieve better cardiovascular health outcomes. Population knowledge regarding CVD is an important precursor for any such interventions [7]. Indeed, a knowledgeable population is more likely to make healthier lifestyle choices, recognize disease risk factors and adopt positive health seeking behaviours [8]. Unfortunately, CVD is a relatively new phenomenon in SSA, and thus most of the population has a limited understanding of the disease and related risk factors. Moreover, available data is inadequate with only a handful of studies examining knowledge [9, 10] and usually with a focus on specific conditions such as stroke [11, 12] and risk factors such as hypertension [13]. To generate evidence for targeted interventions, this study examined knowledge on CVD prevention and associated factors among adults in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda.

Methods

Study design and area

This cross-sectional study was informed by data from the baseline survey of a stepped wedge trial of the Scaling-up Packages of Interventions for Cardiovascular disease prevention in selected sites in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa (SPICES) – project [14]. In Uganda, the project is being implemented in Mukono and Buikwe districts located 35.0 and 57.4 km from Uganda’s capital, Kampala, with a total population of 1,000,000, of whom 50.0% are female [15]. Residents in these districts, 70% of whom live in rural areas, majorly practice subsistence farming, fishing and a section engages in small scale trade.

Study population, sample size and sampling

The study population were residents in the two districts aged between 25 and 70 years with households as study units. The sample size was calculated following Hemming’s formula for a stepped wedge trial as previously described [14]. In the districts, 20 parishes, each that hosted a Health Centre III, were selected. The HC III is situated at the sub-county level with a general outpatient clinic and a maternity ward receiving referrals from HC II (at parish) and HC I (at village) levels and refers to higher levels (HC IV and general hospital) within the district. From each parish, a random sample of four villages was drawn to form the study clusters. A mapping of area boundaries and listing of all households was conducted prior to the study to generate a sampling frame [14]. In the selected villages, a random sample of 200 households was obtained and all adults aged 25–70 years within the households interviewed. Analysis for this paper is based on 4372 respondents from 3689 randomly selected households across 80 villages in the 20 parishes.

Data collection

Data collection for this study was conducted between December 2018 and January 2019 by a team of trained Research Assistants in the study sites using pretested semi-structured questionnaires informed by the healthy-lifestyle counselling module of the WHO Hearts package that details the major behavioural risk factors for CVD [16]. The study developed and utilized two sets of questionnaires, the household and participant questionnaires. The household questionnaire (Additional file 1) captured household information including source of drinking water, type of toilet facility, cooking fuel, floor and roof material of house, household assets such as radio, television, mobile phone and vehicle, which supported development of the socio-economic index, and household income. On the other hand, the participant questionnaire (Additional file 2) had questions on socio-demographic characteristics of respondents including sex, age, education level and occupation, and knowledge on CVD prevention and lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use [14]. The questionnaire also asked whether respondents had ever received advice on health lifestyles and who provided them this advice. The questionnaires were developed in English and translated into Luganda, the most spoken local language in the study area, and uploaded on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software designed with data entry checks and inbuilt skip patterns and installed on smart phones and tablets. Research Assistants approached respondents in their households to respond to questionnaires with household information collected first. Field work was overseen by a team of supervisors.

Data management and analysis

All collected data were transmitted to the server located at the university and data downloaded, reviewed and cleaned and any discrepancies addressed. Data were then imported into STATA version 15.0 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA) statistical software for analysis. Data from both the household and participant questionnaires were merged using prior assigned household numbers. To obtain the composite knowledge score, responses to questions on knowledge were graded and assigned 1 if answered correctly and 0 if otherwise. A total score with the maximum as six was then generated for each respondent. The Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of our knowledge scale was 0.6571. Respondents with a total score of five and above were classified as knowledgeable about CVD prevention (based on Bloom’s cut off point) and assigned a code 1 and the rest assigned a code of 0 to form a binary outcome variable for further data analysis. To obtain the socio-economic index, data collected on household characteristics and assets was fully dichotomized and principal component analysis used to obtain the first principal component explaining household wealth. This variable was then divided into quintiles and categorized into lowest 40% (low), middle 40% (middle) and upper 20% (high).

For the analysis, descriptive statistics were run to characterize the sample and proportions and means reported. Because the study outcome was not rare (> 10%) and the need to control for clustering at parish, village and household levels, prevalence ratios (PRs) were used as a measure of association [17, 18]. The PRs were obtained using mixed-effects Poisson regression analysis with fixed (individual characteristics) and random (parish, village, household) effects and robust standard errors. Separate models were run to obtain factors associated with CVD prevention knowledge at the bivariate level and thereafter, variables with a p-value of < 0.2 were considered for multivariate analysis. Multi-collinearity among independent variables was assessed using the Pearson correlation co-efficient and for any pair of variables with a co-efficient of > 0.4 and p-value < 0.05, only one was included in the multivariate model. Reporting for this study followed the STROBE checklist (Additional file 3).

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Of the 5314 eligible adults, 4372 (82.3%) responded to the survey among whom majority 2632 (60.2%) were female, 1761 (40.3%) were aged between 25 to 35 years (mean age [SD] = 41.4 (±12.7) and just over half 2284 (52.2%) had attained primary education. Most 3287 (76.0%) respondents were farmers or casual labourers, about four in ten 1858 (42.5%) had lived in their areas for over 25 years and just over a third 1357 (36.5%) of their households earned over $28 per month (Table 1).

Knowledge about cardiovascular disease prevention

Table 2 shows a summary of the respondents’ scores on CVD prevention knowledge questions. The mean score of respondents on the scale of 6 questions was 3.1 (±1.43) with most 3596 (82.2%) scoring below 5. Respondents were more knowledgeable about foods high in calories 2981 (68.2%), low fruit and vegetable intake 2892 (66.1%) and high salt consumption 2752 (62.9%) as risk factors for CVD. On the other hand, over three quarters of respondents 3325 (76.1%) thought the recommended weekly moderate physical activity was 30 min and a half 2262 (51.7%) disagreed or did not know that it was possible to have hypertension without any symptoms. Overall, 776 (17.7%) of respondents had high knowledge on CVD prevention.

Advice on healthy lifestyles

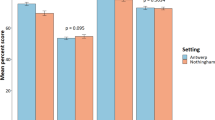

Overall, over half of the respondents 2471 (56.5%) had received advice on at least one of the CVD risk factors with most reporting advice on salt reduction 1772 (40.5%) and physical activity 1512 (34.6%). The major providers of advice were health workers 1217 (28.6%) and friends / relatives 1090 (25.6%) (Fig. 1).

Factors associated with knowledge on cardiovascular disease prevention

Bivariate analysis revealed that education level, occupation, household income, socio-economic index, religion and where respondent lived most adult or childhood life as significantly associated with knowledge on CVD prevention. Furthermore, households that had a radio or television, or a mobile phone and respondents who had ever received advice on healthy lifestyles had significantly higher knowledge. Due to multi-collinearity, place where most childhood was spent, whether respondent was household head and whether respondents had ever had their blood pressure measured were not included in the multivariate analysis. When qualifying variables where adjusted for in a multivariable model, knowledge on CVD prevention was significantly higher among respondents who had completed post-primary education [Adjusted PR = 1.55 (95% CI: 1.18–2.02), p = 0.002], those who were in formal employment [APR = 1.69 (95% CI: 1.40–2.06), p < 0.001] and those who belonged to the high socio-economic index [APR = 1.35 (95% CI: 1.09–1.67), p = 0.004]. Additionally, the proportion of respondents with high CVD prevention knowledge was 35 and 37% higher among those whose households had a mobile phone [APR = 1.35 (95% CI: 1.07–1.70), p = 0.012] and those who had ever received advice on healthy lifestyles [APR = 1.37 (95% CI: 1.14–1.65), p = 0.001] respectively (Table 3). There was no interaction between age and sex.

Discussion

This study examined knowledge on CVD prevention and associated factors among adults aged 25 to 70 years in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda. Overall, knowledge levels were unsatisfactory with less than a fifth of respondents knowledgeable. Factors that were significantly associated with high CVD prevention knowledge were: post-primary education, formal employment, and high socio-economic index. In addition, respondents from households that had a mobile phone and those who had ever received advice on healthy lifestyles were significantly more knowledgeable about CVD prevention.

In our study, only 17.7% of the respondents had high knowledge on CVD prevention. This is consistent with findings from a systematic review on CVD knowledge and awareness among the general population in SSA [19]. Other studies that examined knowledge on specific CVD conditions and risk factors also reported it to be low. For example, a cross-sectional study in Uganda among a mostly urban population found that nearly 75% did not know any risk factors and warning signs for stroke [12], and in another in rural and urban Mukono district, participants rarely mentioned smoking as a stroke risk factor [11]. In Cameroon, although moderate to high knowledge levels on CVD risk factors were reported, overall knowledge scores were equally low and gaps in warning signs for heart attack and stroke were found [20]. Moreover, studies have shown that even with the high prevalence of CVD risk factors such as hypertension in many SSA countries, awareness and control remains low [6, 21, 22] amidst low population knowledge [13, 23] affecting health care seeking, diagnosis and treatment. It is therefore imperative that interventions to improve population knowledge about CVD and its risk factors such as those premised on health promotion and awareness raising are implemented to contribute to prevention and control efforts.

In the study, major sources of advice on CVD risk factors among community members was in the order of health workers, friends or relatives, and radio or television similar to previous research [9, 12]. The fact that informal sources such as friends and relatives were a major source of information to community members could partly explain the low knowledge levels observed in this study and highlights the need for interventions to target such key influencers. Moreover, we found gaps in understanding of key recommendations for CVD preventive practices. For example, although community members knew that physical activity is important for CVD prevention, most did not know the recommended duration for this activity. Whereas over 90% of the population in this community as well as the country are reported to meet the World Health Organization physical activity guidelines, this is majorly through work related activities [5, 24, 25]. Education interventions should therefore go beyond increasing awareness on CVD risk factors but also inculcate an understanding of specific recommendations so that populations have comprehensive information to make informed lifestyle changes. This will maximize the public health benefits of recommended health practices as most are dependent on meeting the minimum thresholds.

Health workers and mass media channels should also play important roles to equip and empower communities with CVD prevention knowledge contributing to improved lifestyle practices. Over 80% of our respondent households had a mobile phone whose ownership was associated with being knowledgeable thus increasing the potential for mobile health interventions, which have shown promise for CVD prevention in low- and middle- income countries [26, 27]. Also, although community health workers were a less reported avenue for advice, our previous research has shown that they are acceptable [28] and thus could be a key resource to target to improve community awareness on CVD especially in low income settings through their routine health promotion activities. Indeed, systematic reviews have demonstrated that community health workers could be effective in tackling the burden of CVD in both low- and- middle income countries [29]. The effectiveness of community health workers could be attributed to their wider reach in many areas, rapport with community members, and delivery of information in the local language [29, 30]. Thus, the SPICES project is implementing interventions targeting community health workers [14] to improve community knowledge and CVD prevention practices [25] in Mukono and Buikwe districts.

A SSA systematic review found that knowledge on CVD and risk factors was significantly influenced by population studied, place of residence and exposure to health information [19]. Indeed, in this study, CVD prevention knowledge was significantly higher among adults with post-primary education, those involved in formal occupations, those from a high socio-economic index, and respondents who had ever received advice on healthy lifestyles. Higher education as a predictor of high knowledge on CVD has been reported in previous studies in SSA [9, 12, 19, 20] and in high income countries [31, 32]. Education levels are also associated with occupation with higher educated individuals involved in more formal occupations and more likely to belong to a higher socio-economic index. A study in Cameroon found that beyond high level of education, a high monthly income was associated with moderate-to-good knowledge on CVD [20]. Other studies have also identified urban residence as influential in acquisition of CVD knowledge attributed to access to health information and higher services proximity [33, 34]. Moreover, in our study, those who had received health information or advice had higher CVD knowledge. It thus remains paramount to fully equip communities with key and comprehensive information on CVD prevention as a key measure to deal with the disease.

Study limitations and strengths

This study was limited by the lack of a validated questionnaire on CVD prevention knowledge and although there was a possibility of information bias, this was unlikely since questions asked were very specific to which respondents indicated agreement or not. On the other hand, we delved into assessing comprehensive knowledge reducing information and social desirability biases as opposed to most previous studies. Also, previous studies majorly looked at knowledge on individual CVD risk factors or conditions unlike our study which had a broader scope. The study had a large sample size of adults selected rigorously from a well-defined sampling frame and was conducted in an area similar in context and characteristics with other parts of Uganda increasing potential for generalizability. The results may also be generalizable to similar contexts in African countries at same level of development.

Conclusion

This study shows very low CVD knowledge with major gaps around recommended physical activity duration, diet and whether hypertension is asymptomatic. Indeed, less than a fifth of study respondents were knowledgeable on CVD prevention which was significantly higher among those who had post-primary education, were in formal occupation and belonged to a high socio-economic index. In addition, respondents from households that had a mobile phone and those who had ever received advice on healthy lifestyles were significantly more knowledgeable about CVD prevention. Observed knowledge gaps should inform suitable interventions and strategies to equip and empower communities with sufficient information for CVD prevention.

Availability of data and materials

The data used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APR:

-

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- SPICES:

-

Scaling up Packages of Interventions for Cardiovascular disease prevention in selected sites in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa;

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

References

Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, Barber R, Nguyen G, Feigin VL, Naghavi M, Mensah GA, Murray CJL. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1333–41.

Hamid S, Groot W, Pavlova M. Trends in cardiovascular diseases and associated risks in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the evidence for Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania. Aging Male. 2019;22(3):169–76.

BeLue R, Okoror TA, Iwelunmor J, Taylor KD, Degboe AN, Agyemang C, Ogedegbe G. An overview of cardiovascular risk factor burden in sub-Saharan African countries: a socio-cultural perspective. Glob Health. 2009;5(1):10.

Guwatudde D, Mutungi G, Wesonga R, Kajjura R, Kasule H, Muwonge J, Ssenono V, Bahendeka SK. The epidemiology of hypertension in Uganda: findings from the national non-communicable diseases risk factor survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138991.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Global Health. 2018.

Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F. Prevalence, awareness and control of hypertension in Uganda. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62236.

Mohd Azahar NMZ, Krishnapillai ADS, Zaini NH, Yusoff K. Risk perception of cardiovascular diseases among individuals with hypertension in rural Malaysia. Heart Asia. 2017;9(2):e010864.

Bergman HE, Reeve BB, Moser RP, Scholl S, Klein WM. Development of a comprehensive heart disease knowledge questionnaire. Am J Health Educ. 2011;42(2):74–87.

Temu TM, Kirui N, Wanjalla C, Ndungu AM, Kamano JH, Inui TS, Bloomfield GS. Cardiovascular health knowledge and preventive practices in people living with HIV in Kenya. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):421.

Uchenna D, Ambakederemo T, Jesuorobo D. Awareness of heart disease prevention among patients attending a specialist clinic in southern Nigeria. Int J Prev Treat. 2012;1:40–3.

Kaddumukasa M, Kayima J, Kaddumukasa MN, Ddumba E, Mugenyi L, Pundik S, Furlan AJ, Sajatovic M, Katabira E. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of stroke: a cross-sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:819.

Nakibuuka J, Sajatovic M, Katabira E, Ddumba E, Byakika-Tusiime J, Furlan AJ. Knowledge and perception of stroke: a population-based survey in Uganda. ISRN stroke. 2014;2014.

Agyei-Baffour P, Tetteh G, Quansah DY, Boateng D. Prevalence and knowledge of hypertension among people living in rural communities in Ghana: a mixed method study. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(4):931–41.

Musinguzi G, Wanyenze RK, Ndejjo R, Ssinabulya I, van Marwijk H, Ddumba I, Bastiaens H, Nuwaha F. An implementation science study to enhance cardiovascular disease prevention in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda: a stepped-wedge design. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):253.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics; 2016.

World Health Organization: Hearts: technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care. 2016.

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21.

Santos CAST, Fiaccone RL, Oliveira NF, Cunha S, Barreto ML, do MBB C, Moncayo A-L, Rodrigues LC, Cooper PJ, Amorim LD. Estimating adjusted prevalence ratio in clustered cross-sectional epidemiological data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):80.

Boateng D, Wekesah F, Browne JL, Agyemang C, Agyei-Baffour P, Aikins Ad-G, Smit HA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K: Knowledge and awareness of and perception towards cardiovascular disease risk in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017, 12(12):e0189264.

Aminde LN, Takah N, Ngwasiri C, Noubiap JJ, Tindong M, Dzudie A, Veerman JL. Population awareness of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Buea, Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):545.

Ataklte F, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Taye B, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Kengne AP. Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):291–8.

Kayima J, Wanyenze RK, Katamba A, Leontsini E, Nuwaha F. Hypertension awareness, treatment and control in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13(1):54.

Chimberengwa PT, Naidoo M, on behalf of the cooperative inquiry g. Knowledge, attitudes and practices related to hypertension among residents of a disadvantaged rural community in southern Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0215500.

Guwatudde D, Kirunda BE, Wesonga R, Mutungi G, Kajjura R, Kasule H, Muwonge J, Bahendeka SK. Physical activity levels among adults in Uganda: findings from a countrywide cross-sectional survey. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:938–45.

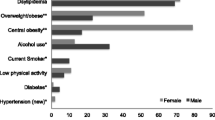

Musinguzi G, Ndejjo R, Ssinabulya I, Bastiaens H, van Marwijk H, Wanyenze RK. Cardiovascular risk factor mapping and distribution among adults in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda: small area analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):284.

Beratarrechea A, Lee AG, Willner JM, Jahangir E, Ciapponi A, Rubinstein A. The impact of mobile health interventions on chronic disease outcomes in developing countries: a systematic review. Telemedicine E-Health. 2014;20(1):75–82.

Liu Z, Chen S, Zhang G, Lin A. Mobile phone-based lifestyle intervention for reducing overall cardiovascular disease risk in Guangzhou, China: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(12):15993–6004.

Ndejjo R, Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F, Wanyenze RK, Bastiaens H. Acceptability of a community cardiovascular disease prevention programme in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):75.

Khetan AK, Purushothaman R, Chami T, Hejjaji V, Madan Mohan SK, Josephson RA, Webel AR. The Effectiveness of Community Health Workers for CVD Prevention in LMIC. Global Heart. 2017;12(3):233–43 e236.

Hill J, Peer N, Oldenburg B, Kengne AP. Roles, responsibilities and characteristics of lay community health workers involved in diabetes prevention programmes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189069.

Potvin L, Richard L, Edwards AC. Knowledge of cardiovascular disease risk factors among the Canadian population: relationships with indicators of socioeconomic status. CMAJ. 2000;162(9 Suppl):S5–S11.

Awad A, Al-Nafisi H. Public knowledge of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1131.

Chikafu H, Chimbari MJ. Cardiovascular disease healthcare utilization in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):419.

Kiwanuka SN, Ekirapa EK, Peterson S, Okui O, Rahman MH, Peters D, Pariyo GW. Access to and utilisation of health services for the poor in Uganda: a systematic review of available evidence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(11):1067–74.

Acknowledgments

The Research Assistants who collected the data and the project team that provided administrative support are appreciated.

Funding

This study was funded under the SPICES project in Uganda which received funding from the European Commission through the Horizon 2020 research and innovation action grant agreement No 733356 to implement and evaluate a comprehensive CVD prevention program in five settings: a rural & semi-urban community in a low-income country (Uganda), middle income (South Africa) and vulnerable groups in three high-income countries (Belgium, France and United Kingdom). The funder had no role in the design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The contents of this article are the views of the authors alone and do not represent the views of the European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RN contributed to the design of the study, data collection, led the analysis, interpretation of results and drafting of the manuscript. FN contributed to the design of the study, analysis and critical review of the draft manuscript. HB and RKW contributed to the design of the study and critical review of the draft manuscript. GM contributed to the design of the study, data collection, analysis and critical review of the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee of Makerere University School of Public Health (protocol 624) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS 2477). The district authorities provided permission for the study and participants gave written informed consent before participation. All collected data were confidentially treated to protect the privacy and confidentiality of study participants and was only accessible to the study investigators.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Household Demographics Questionnaire

Additional file 2.

Spices Project Participant's Questionnaire

Additional file 3.

STROBE Checklist

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ndejjo, R., Nuwaha, F., Bastiaens, H. et al. Cardiovascular disease prevention knowledge and associated factors among adults in Mukono and Buikwe districts in Uganda. BMC Public Health 20, 1151 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09264-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09264-6