Abstract

Background

Childhood immunization programmes have made substantial contributions to lowering the burden of disease among children in developing countries, however a large proportion of children still remain unimmunized. This study aimed to explore the determinants of rotavirus vaccine (RVV) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) uptake in Ethiopia.

Methods

The 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey dataset was used in this analysis. A total of 2004 children aged 12–23 months were included in the analysis. A multivariable logistic regression model was employed to identify the determinants of uptake of the complete schedules of RVV (two doses) and PCV (three doses). Crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Results

The uptakes of the complete schedules of RVV and PCV among children aged 12–23 months were 56 and 49.1%, respectively. The likelihood of immunization with the complete schedule of RVV was significantly lower among children from the relatively poor Afar region in Ethiopia (AOR 0.16; 95%-CI 0.04–0.61). Similarly, children living in not only the Afar region (AOR 0.10; 95%-CI 0.03–0.38), but also the Gambela region (AOR 0.25; 95%-CI 0.08–0.83), were less likely to be vaccinated with PCV. On the other hand, children from more wealthy households had higher odds of vaccination with RVV (AOR 1.69; 95%-CI 1.04–2.75). Also attending antenatal care (ANC) was found to be significantly associated with uptake of the complete schedule of RVV and PCV.

Conclusions

The uptake of RVV and PCV is suboptimal in Ethiopia. The uptake of the vaccines were found to be associated with region, ANC use and wealth status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diarrhea and pneumonia are the cause of heavy health burdens across the world [1, 2]. Globally, in 2011, diarrhea and pneumonia were respectively responsible for the death of 0.7 and 1.3 million children under the age of five [1]. In Ethiopia, diarrhoea and pneumonia are the two leading causes of morbidity and mortality among children in this age group [3, 4]. In addition, a considerable economic burden was reported in Ethiopia due to the extensive household expenditures of treating diarrhoea or pneumonia [5]. In the absence of targeted immunization programmes, rotavirus is associated with 28% of severe diarrheal cases and Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible for 18% of cases of severe pneumonia [1].

The effectiveness of rotavirus vaccines (RVVs) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) in preventing gastroenteritis and pneumonia has been established [6, 7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the introduction of these vaccines into the immunization schedules of developing countries with high background rates of childhood mortality [8, 9]. Following the recommendation, the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) of Ethiopia introduced into the routine childhood immunization schedule the 10-valent PCV (PCV10) in 2011 and the RVV in 2013 with financial support from the GAVI Alliance [10].

The uptake of a vaccine is one of the key performance indicators of immunization programmes [11]. According to the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP)—which was endorsed at the 65th World Health Assembly in May 2012— all countries should plan to reach 90% national coverage of three doses of diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DTP) vaccines by 2015 and all vaccines in national vaccination programmes by 2020 [12]. However, the WHO’s report indicated that global immunization coverage was only at 85% in 2017, and 19.9 million children did not receive routine life-saving vaccinations in that same year. The report also showed that the coverage level for new and underused vaccines remains low only 28% for RVV and 44% for PCV [13].

Despite the government’s improvement measures in Ethiopia—such as the Reach Every District (RED) approach and health extension programme—full immunization coverage in the country remained very low at 33.3% for all age-appropriate vaccinations, including three doses of PCV and two doses of RVV. In addition, there is marked heterogeneity of the vaccination coverage across different regions of the country [10, 14,15,16]. In Ethiopia, studies that were conducted to identify factors associated with immunization coverage among children commonly focused on full immunization coverage [17,18,19]. Few studies have also investigated determinants of coverage for specific vaccines included in the national expanded programme on immunization (EPI) [20, 21]. So far, however, very little attention has been paid to newly introduced vaccines such as RVV and PCV. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the factors associated with uptake of RVV and PCV in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design

A secondary analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data was conducted. The EDHS is a population-based cross-sectional household survey which was conducted in nine regions (Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromiya, Somali, Benishangul Gumuz, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP), Gambela, and Harari) and two administrative cities (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) in Ethiopia. The detailed study design of the EDHS was described elsewhere [15].

Sampling technique

The 2016 EDHS employed a stratified sampling technique to recruit study participants. Each region was stratified into urban and rural areas, yielding 21 sampling strata. In the first stage, a total of 645 clusters were selected from urban (202 clusters) and rural (443 clusters) areas with a sampling probability proportional to the population size. Then households in each of the selected clusters were listed and used as a sampling frame for the selection of households. In the second stage, a fixed number of 28 households in each cluster were selected by equal probability systematic sampling in the selected cluster. The final survey was conducted in 5232 and 11,418 residential households in urban and rural areas, respectively. All women between 15 and 49 years of age, who were either permanent residents of the selected households or visitors who stayed in the household the night before the survey, were eligible to be interviewed. Accordingly, complete interviews were conducted with 15,683 women, corresponding to a response rate of about 95% [15].

Data collection

Data on the vaccination status of the children was collected from the mother’s report and/or vaccination card (this also includes a booklet or other home-based record). If the card was available at home or health facility, information about the vaccination status was directly obtained from the vaccination card. Otherwise, the mother was asked to recall all vaccinations received by their children. According to the 2016 EDHS, data collectors were able to see a vaccination card at home for 34.1% of children aged 12–23 months [15].

Study variables

The vaccination statuses for RVV and PCV for children aged 12–23 months were the outcome variables. Children in this age group are expected to have received the complete schedule of these vaccines, according to the EPI schedule in Ethiopia (Table 1). The vaccination status was considered separately for the two vaccines. A child who received two doses of RVV and three doses of PCV was considered “fully vaccinated” with the respective vaccines whereas a child who did not receive at least one dose of the vaccines was categorized as “not (fully) vaccinated”. The independent variables included in this study were the following:

Mother’s characteristics, including age at child birth, education level, marital status, occupation, religion, region, residence place, exposure to media (i.e. access to newspaper, radio and television; those who had access to any of these three outlets at least once a week were considered as exposed to media and others were considered not exposed), use of ANC (≥ 4 ANC visits was considered as adequate, whereas 1–3 visits was considered as inadequate [22]), place of delivery, postnatal check-up and the perception that the distance to a health facility was a big problem.

Partner’s level of education and occupation.

Child’s characteristics including sex and birth order.

Household wealth index, a composite measure of the socioeconomic status of the household used for ranking the households from poorest to richest quantiles. It is measured based on assets ownership and housing characteristics including a source of drinking water, type of toilet facilities, type of cooking fuel, materials used for housing construction, ownership of land, and other assets.

Analysis

Stata 15.1 was used for data analysis (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). Descriptive statistics were employed to determine the distribution of independent variables by vaccination status. A chi-square test was used to test whether there were associations between vaccination status and background characteristics. Bivariate analysis was used to separately evaluate the effect of each independent variable on the outcome variable and the variables with a p-value <0.25 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression models [23]. Child’s sex as a demographic characteristic was added in the final model [24]. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was employed to detect the presence of multicollinearity among independent variables at the cutoff point of 10 [25]. As a result, partner occupation with VIF greater than 10 was omitted from the multivariate logistic regression models. An F-adjusted mean residual goodness-of-fit test was utilized to check the goodness-of-fit in the final model [26]. Due to the survey sample designs employed in DHS, svyset command in Stata 15.1 was used in order to account for inverse probability weights [15, 27].

Results

In this study, the vaccination status of 2004 Ethiopian children was assessed. More than half (53.8%) of the children were female, slightly over one-third (36.6%) were delivered in health facilities, and 71.8% of all children were born within the first five in their birth order. The vast majority of the children were rural dwellers (88.4%), and their mothers were between 20 and 34 years of age (73.2%). Only 8.5% of the children had a mother who attended secondary or higher education and 45.7% of the children had a mother who was involved in some kind of work. In terms of religion, about two-fifths (39.2%) of the children had a Muslim mother, followed by Orthodox Christian (34.8%), Protestant (22.2%) or other (3.8%). Of the children, 25.2, 19.8, 22.4, 18.3, and 14.4% lived in the poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest households, respectively. More than 62% of the children belonged to mothers who attended at least one ANC service during their pregnancy (Table 2).

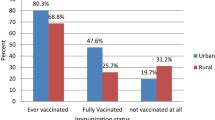

It was found that 56 and 49.1% of the children received the complete schedule of RVV and PCV, respectively (Table 2, Additional file 1). Across regions, immunization coverage with the complete schedule of RVV ranged from 23.3% in Afar to 91.7% in Addis Ababa, and from 17.5% in Afar to 91.4% in Addis Ababa for PCV (Table 2). According to bivariate analysis, uptake of RVV and PCV were associated with various background characteristics (Table 3). Vaccination of children with complete schedules of RVV and PCV was significantly associated with educational level, religion, region, wealth quantile, and working status of the mothers. Similarly, vaccines uptake were associated with paternal educational and working status. Moreover, the likelihood of complete schedule uptake of the vaccines was higher among children of mothers who received ANC, gave birth in a health facility, or visited a health facility within 2 months after delivery for a postnatal check-up. The mother’s exposure to mass media was also positively associated with the uptake of RVV and PCV. The uptake of RVV and PCV was higher in urban areas compared to rural areas and the uptake of the vaccines was also higher among children of mothers who do not consider distance to a health facility as a big problem. The uptake of the complete schedule of both RVV and PCV did not significantly vary between male and female children.

Table 3 also shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression. After adjusting for other variables, factors that remained significant predictors for the uptake of the complete schedule of RVV and PCV were region, wealth index and ANC utilization. Accordingly, as borne out in this analysis, children from the Afar region were less likely to be fully vaccinated with RVV (AOR 0.16; 95%-CI 0.04–0.61; p < 0.05) compared to children in Addis Ababa. Likewise, children living in Afar or Gambela were 0.10 and 0.25 times less likely to be vaccinated with the complete schedule of PCV, respectively, compared to those in Addis Ababa. There appeared to be a trend that children of mothers from the richer wealth groups were more likely to be vaccinated. Indeed, children from the richer wealth quantile were 1,69 times more likely to receive the complete schedule of RVV (AOR 1.69 95%-CI 1.04–2.75; p = 0.036). For PCV vaccination, the trend was similar but not statistically significant. The uptake of RVV and PCV was significantly higher among children born to mothers who had adequate ANC visits (4 or more than 4 visits) compared to those born to mothers who had no ANC visit at all (AOR 2.79 95%-CI 1.73–4.51; p < 0.001 and AOR 3.27 95%-CI 2.04–5.23; p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, mothers with inadequate ANC visits (less than 4 visits) were also more likely to have their children vaccinated with the complete schedule of RVV (AOR 1.64 95%-CI 1.06–2.53; p < 0.001) or PCV (AOR 2.20 95%-CI 1.43–3.37; p = 0.025) than those with no ANC visit at all.

Discussion

In developing countries, where the economic and public health burden of vaccine-preventable disease is substantial, the potential benefit of including new vaccines in national immunization programmes against diseases not previously covered by the existing programmes is enormous [28]. Working towards achieving high universal coverage is also a key issue in order to optimize the benefits of vaccination programmes. Therefore, policymakers need to closely monitor vaccination coverage and take evidence-based measures to stimulate vaccine uptake and reduce coverage inequalities among different segments of the population. This study aimed to identify the factors associated with the uptake of two newly introduced vaccines, RVV and PCV, in Ethiopia.

It was found that 56 and 49.1% of the Ethiopian children were vaccinated with the complete schedule of RVV and PCV, respectively. The slight difference in coverage between the two vaccines might be attributed to the difference in the number of doses of the vaccines—2 for RVV versus 3 for PCV. Compared to the two-dose RVV, there is a higher possibility of dropout for the three-dose PCV [29]. Slight differences in coverage between the two vaccines have also been noted elsewhere [30]. According to the EDHS report, the coverage also varies between other vaccines included in the routine EPI schedule in Ethiopia [15]. The observed coverage of the two vaccines in Ethiopia is far below the target (>90%) set by the country [10].

There are several factors that can predict childhood immunization coverage [31]. In our analysis, we identified that administrative regions, wealth status, and ANC visits were significantly associated with uptake of the complete schedule of RVV and PCV. With regard to administrative regions, children in the Afar or Gambela regions were less likely to be (fully) vaccinated with RVV or PCV. Likewise, children who live in Afar or Gambela were also less likely to receive the complete schedule of PCV. In Afar and Gambela, significant proportions of the population are pastoralists, commonly moving from one place to another in search of food and water, which makes the provision of health care services challenging including childhood immunization. Moreover, as emerging/developing regions, Afar and Gambela are characterized by fragile health care systems often with poor organization and inadequate infrastructure compared to other regions in the country. This makes it even more difficult to provide vaccination services. Regional variation of immunization coverage within a country has also been documented in several studies from other developing countries [18, 24, 30, 32,33,34].

Wealth-based health inequality is a major impediment for the realization of universal health-care coverage. In this study, children from the richer wealth quantile were more likely to receive the complete schedule of RVV. Although childhood immunization by itself is free of charge in Ethiopia, there is nevertheless a heavy economic burden associated with childhood vaccination due to travel costs and forgone income because of work loss while seeking immunization services for the children. This finding is in concordance with that in other previous studies [32, 33, 35, 36].

As noted previously [19, 24, 33, 37,38,39], our study showed that childhood vaccination with RVV and PCV was found to be significantly associated with ANC service utilization. The odds of vaccination with complete schedule RVV and PCV were 2.8 and 3.3 times higher for children whose mothers received adequate ANC (≥4 visit) and 1.6 and 2.2 times higher for children whose mothers received inadequate ANC (< 4 visit), compared to those whose mothers had not made any ANC visit at all. This may be explained by the fact that ANC visits might have improved the mothers’ knowledge and attitude towards the importance of childhood vaccination. In addition, prior experience and interaction during ANC might build trust towards vaccination services, which is important for reducing the vaccine confidence gap in the community.

The strength of the current study is that it is based on nationwide data. However, there are several limitations as well. Firstly, since mothers’ self-report is used as a source of information for the child’s immunization status, there is a possibility of recall bias. However, a study in Tanzania documented a high accuracy and minimal bias due to parental recall during estimation of vaccination coverage compared to card-based data [40]. Secondly, in our study, we focused mainly on the demand side of the determinants and did not assess the effect of the supply side on the uptake of vaccines, because these data are lacking in the EDHS. Clearly, vaccine supply will also have a significant effect on immunization coverage. Lastly, the current study is focusing only on vaccines newly introduced to the country. Despite this limitation, the findings of this study will provide transferable lessons for other vaccine programs within Ethiopia especially for those having the same schedule with vaccines under consideration in our study.

Conclusions

The overall coverage of RVV and PCV among children between 12 and 23 months of age was suboptimal and below the national target in Ethiopia. Regional variation, wealth status and utilization of ANC were found to be significant predictors for the uptake of the vaccines. Vaccination coverage among children from the Afar and Gambela regions, as well as among those from the poorest sections of the population, was found to be minimal. Hence, this study emphasizes the need for specific interventions, that take regional and wealth status differences into consideration, in order to improve childhood vaccination coverage in the country. Policy makers might consider expanding ANC service utilization among mothers as a potential strategy to improve childhood immunization coverage in Ethiopia.

Availability of data and materials

Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016 data was used in this study; it is available for public use upon registration and request to DHS program at https://dhsprogram.com/

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- DTP:

-

Diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- EPI:

-

Expanded programme on immunization

- GVAP:

-

Global Vaccine Action Plan

- PCV:

-

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- RED:

-

Reach Every District

- RVV:

-

Rotavirus vaccine

- SNNP:

-

Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–16.

GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544.

Deribew A, Tessema GA, Deribe K, Melaku YA, Lakew Y, Amare AT, et al. Trends, causes, and risk factors of mortality among children under 5 in Ethiopia, 1990–2013: findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Popul Health Metrics. 2016;14(1):42.

UNICEF. Committing to Child Survival: A Promise Renewed Progress Report. New York; 2014. Cited 2019 Jan 11]. Available from: http://files.unicef.org/publications/files/APR_2014_web_15Sept14.pdf

Memirie ST, Metaferia ZS, OF N, Levin CE, Verguet S, Johansson KA. Household expenditures on pneumonia and diarrhoea treatment in Ethiopia: a facility-based study. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(1):e000166.

Soares-Weiser K, Maclehose H, Bergman H, Ben-Aharon I, Nagpal S, Goldberg E, et al. Vaccines for preventing rotavirus diarrhoea: vaccines in use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008521.

Ewald H, Briel M, Vuichard D, Kreutle V, Zhydkov A, Gloy V. The Clinical Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Dtsch Aerzteblatt Online. 2016; Available from: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0139

World Health Organization. Rotavirus vaccines WHO position paper: January 2013 – recommendations. Vaccine. 2013;31(52):6170–1.

Publication WHO. Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper – 2012 – Recommendations. Vaccine. 2012;30(32):4717–8.

EFMoH. Ethiopia National Expanded Program on Immunization, Comprehensive Multi - Year Plan 2016–2020. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health; 2015.

World Health Organization. WHO | Strategic indicators. WHO. World Health Organization; 2014 [Cited 2019 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/routine/indicators/en/

World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan. 2013.

WHO. Immunization coverage. [Cited 2019 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage

Wondwossen L, Gallagher K, Braka F, Karengera T. Advances in the control of vaccine preventable diseases in Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:1.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Belete H, Kidane T, Bisrat F, Molla M, Mounier-Jack S, Kitaw Y. Routine immunization in Ethiopia. J Heal Dev. 2015;1:2–7.

Regassa N, Bird Y, Moraros J. Preference in the use of full childhood immunizations in Ethiopia: the role of maternal health services. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:91–9.

Lakew Y, Bekele A, Biadgilign S. Factors influencing full immunization coverage among 12–23 months of age children in Ethiopia: evidence from the national demographic and health survey in 2011. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):728.

Etana B, Deressa W. Factors associated with complete immunization coverage in children aged 12–23 months in ambo Woreda, Central Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):566.

Tsehay AK, Worku GT, Alemu YM. Determinants of BCG vaccination coverage in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2).

Geremew TT, Gezie LD, Abejie AN. Geographical variation and associated factors of childhood measles vaccination in Ethiopia: a spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1.

World Health Organization. WHO antenatal care randomized trial: manual for the implementation of the new model. Geneva: World Health Organization. Geneva; 2002.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

Mbengue MAS, Sarr M, Faye A, Badiane O, Camara FBN, Mboup S, et al. Determinants of complete immunization among senegalese children aged 12-23 months: evidence from the demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):630.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education Limited; 2014.

Archer KJ, Lemeshow S. Goodness-of-fit test for a logistic regression model fitted using survey sample data. Stata J. 2006;6(1):97–105.

Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK, et al. Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF; 2018.

Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1645):20130433.

Baguune B, Ndago JA, Adokiya MN. Immunization dropout rate and data quality among children 12–23 months of age in Ghana. Arch Public Heal. 2017;75(1):18.

Ntenda PAM, Mwenyenkulu ET, Putthanachote N, Nkoka O, Mhone TG, Motsa MPS, et al. Predictors of uptake of newly introduced vaccines in Malawi - monovalent human rotavirus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: evidence from the 2015-16 Malawi demographic and health survey. J Trop Pediatr. 2019;65(3):287–96.

Phillips DE, Dieleman JL, Lim SS, Shearer J. Determinants of effective vaccine coverage in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and interpretive synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):681.

Sheikh N, Sultana M, Ali N, Akram R, Mahumud R, Asaduzzaman M, et al. Coverage, timelines, and determinants of incomplete immunization in Bangladesh. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(3):72.

Herliana P, Douiri A. Determinants of immunisation coverage of children aged 12–59 months in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e015790.

Bugvi AS, Rahat R, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F, Nasrullah M, et al. Factors associated with non-utilization of child immunization in Pakistan: Evidence from the Demographic and Health Survey 2006–07. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:232.

Devasenapathy N, Ghosh Jerath S, Sharma S, Allen E, Shankar AH, Zodpey S. Determinants of childhood immunisation coverage in urban poor settlements of Delhi, India: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e013015.

Rahman M, Obaida-Nasrin S. Factors affecting acceptance of complete immunization coverage of children under five years in rural Bangladesh. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(2):134–40.

Adedokun ST, Uthman OA, Adekanmbi VT, Wiysonge CS. Incomplete childhood immunization in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):236.

Hemat S, Takano T, Kizuki M, Mashal T. Health-care provision factors associated with child immunization coverage in a city centre and a rural area in Kabul, Afghanistan. Vaccine. 2009;27(21):2823–9.

Bondy JN, Thind A, Koval JJ, Speechley KN. Identifying the determinants of childhood immunization in the Philippines. Vaccine. 2009;27(1):169–75.

Binyaruka P, Borghi J. Validity of parental recalls to estimate vaccination coverage: evidence from Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):440.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Measure DHS programme for granting permission to use the data.

Funding

AW’s Ph.D. project is funded by the Netherlands Organization for International Cooperation in Higher Education (NUFFIC) and this study is part of his Ph.D. project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW designed the study in consultation with MJP, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. QC was involved in the data analysis and revised the manuscript. MJP and JCW interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The 2016 EDHS data is available for public use by request from the Measure Demographic and Health Survey (Measure DHS) website (https://dhsprogram.com). Permission to use the data was obtained from the Measure DHS programme after describing the objective of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Prof Postma reports grants and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies, including those developing, producing and marketing rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Percentage* of children aged 12–23 months who are fully vaccinated with RVV and PCV in Ethiopia, by a source of information (Vaccination card‡ seen at home, Vaccination record at health facility†, Mother’s report and Any source), Ethiopia DHS 2016.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wondimu, A., Cao, Q., Wilschut, J.C. et al. Factors associated with the uptake of newly introduced childhood vaccinations in Ethiopia: the cases of rotavirus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. BMC Public Health 19, 1656 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8002-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8002-8