Abstract

Background

Policymakers can adopt and implement various supply-side policies to limit youth access and exposure to tobacco, such as increasing the minimum age of sale, limiting the number or type of tobacco outlets, or banning the display of tobacco products. Many studies have assessed the impact of these policies, while less is known about the preceding policy process. The aim of our review was to assess the available evidence on the preceding process of agenda setting, policy formulation, and policy legitimation.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using the PubMed and the Social Sciences Citation Index databases. After selection, 200 international peer-reviewed articles were identified and analyzed. Through a process of close reading, evidence based on scientific enquiry and anecdotal evidence on agenda setting, policy formulation and policy legitimation was abstracted from each article.

Results

Scientific evidence on the policy process is scarce for these policies, as most of the evidence found was anecdotal. Only one study provided evidence based on a scientific analysis of data on the agenda setting and legitimation phases of policy processes that led to the adoption of display bans in two Australian jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The processes influencing the adoption of youth access and exposure policies have been grossly understudied. A better understanding of the policy process is essential to understand country variations in tobacco control policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Youth smoking continues to be a widespread public health problem. Globally, an estimated 7.0% of children aged 13–15 smoke; the Americas (13.0%) and the European region (9.8%) demonstrate the highest prevalence of smoking among children [1]. Youth smoking can be prevented in various ways. One of the strategies is to reduce youth access to tobacco products. The policy most often used to achieve this reduction of access is raising the minimum age-of-sale for the purchase of tobacco. Most countries have implemented this policy, in line with the recommendations of Article 16 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which aims to reduce sales to and by minors [2]. Reviews examining the effectiveness of age-of-sale policies report mixed and inconclusive findings and urge the consideration of enforcement conditions and personal characteristics [3,4,5,6,7]. A reduction in illegal sales to minors does not necessarily mean that youth tobacco consumption is also decreased, because minors can often still access tobacco through social sources [8]. This is one of the reasons some authors have concluded that age-of-sale policies are ineffective [9]. Others conclude that such policies may be effective, as long as they are well enforced [10].

Youth access to tobacco may also be reduced by limiting the number or type of tobacco outlets. Tobacco retailing throughout the world is completely normalized, and “tobacco can be sold openly, from virtually any business” [11]. Policy measures directly limiting the number of tobacco outlets, for example, to specialized shops, have rarely been adopted. Thus far, only the Hungarian government has done so, substantially reducing the number of outlets from 42,000 to 7000, with the explicit aim to decrease smoking prevalence [12]. It can be argued from the perspective of economic theory that a higher tobacco retail density leads to increased tobacco consumption due to increased availability and reduced retrieval costs [13]. However, because policies that reduce the number of sale outlets are rarely adopted, there is limited data on their effectiveness. Some, but not all, studies on this subject have reported positive associations between tobacco outlet density and smoking behavior [14,15,16]. However, because the studies all used observational research designs, causality cannot be inferred [17].

Next to increasing the age of sale and limiting the absolute number of outlets, policymakers may choose to ban the sale of tobacco from certain types of retail outlets. Sale restrictions may be related to the primary function of the sale outlet, which can be in conflict with tobacco sales, such as in the case of pharmacies [18]. Another option is a ban on tobacco vending machines, which may offer easy access of tobacco to minors. To address this issue, Article 16 of the FCTC recommends putting into place a ban on vending machines, or at least some restrictions on accessibility [2]. Many countries have addressed this issue; a total of 89 countries worldwide now have a ban on tobacco vending machines [19].

Directly limiting the number of tobacco retailers may be a step too far for policymakers, which is perhaps indicated by the small number of countries that have adopted this policy measure thus far. An alternative option for policymakers may be to consider banning tobacco displays at points of sale, which will not reduce physical access but aims to reduce exposure to pro-smoking messages at points of sale. Studies and reviews have demonstrated positive associations between exposure to tobacco displays and youth smoking behavior and susceptibility [20,21,22,23,24]. A growing number of countries have adopted a display ban [22, 25, 26], and evaluations of the countries that have implemented this ban suggest that it helps to denormalize smoking [27,28,29].

While there is an emerging body of literature on the effectiveness of the various policies that limit youth access and exposure to tobacco, less is known about the preceding policy process that leads to their adoption by policymakers. In fact, most public health research is carried out without considering the policy process at all [30]. Public health advocates and professionals who want to effectively use the political arena need to have at least a basic understanding of how policymaking works [31]. The more thoroughly this process is examined, the better these individuals can anticipate constraints and opportunities for policy change [32].

There are several theories that may be used to study the preceding process of policymaking up until policy adoption, such as Kingdon’s three streams [33], the punctuated equilibrium theory [34], the advocacy coalition framework [35], theories on multilevel governance [36], theories on policy transfer [37, 38] and others. These theories focus on different aspects of the policymaking process, which are relevant to different stages of the policymaking process. Cairney (2012) breaks down the policy process into the following six stages: agenda setting, policy formulation, legitimation, implementation, evaluation, and policy maintenance, succession or termination [39]. In the current paper, we are interested in the first three stages, as these are relevant to the adoption of policies. Agenda setting refers to the identification of policy problems (e.g., a high level of youth smoking). Formulation refers to the selection of appropriate solutions for the policy problem (e.g., an age-of-sale policy). Legitimation refers to ensuring that the chosen policy has enough political and public support. While much is known about the impacts of policy, considerably less is known about its antecedents [40]. A better insight into the stages up until policy adoption is of vital importance for advocates that wish to foster tobacco control policy.

The aim of this paper is to assess the scientific evidence on the first three stages of the policymaking process of raising the legal age for the purchase of tobacco, limiting the number or type of tobacco outlets, and banning tobacco displays at points of retail. We will assess the quantity and quality of the evidence that can be found in the international scientific literature.

Methods

We conducted a literature search to find evidence on the agenda setting, policy formulation and policy legitimation stages of the policy cycle for the three policies under study. The search strategy was informed by a quick scan of the literature and by a priori inspection of the case of the Netherlands. In this preparatory step, we examined Dutch parliamentary documents about the emergence of tobacco control legislation from 1995 onwards. In addition, we interviewed a member of parliament, a civil servant, and an academic expert, and questions were sent by e-mail to international tobacco control experts. These sources provided us with relevant insights into the policymaking process of the three policies. We translated this knowledge into keywords for our search strategy (see the Additional file 1).

We conducted a literature search using the PubMed and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) databases. Whereas the first database predominantly covers biomedical journals, the SSCI covers a wide range of 176 political science journals. We searched for articles published in peer-reviewed journals up to March 2016. We set no publication date requirement for the articles to be included because countries differed in the timing of policy adoption.

Screening

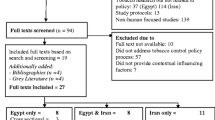

The search yielded 507 references to international peer-reviewed articles. After removing 145 duplicates, 362 articles remained for title and abstract screening. The selection of studies was performed in two stages by two reviewers: TGK and Paulien Nuyts (a project member). During the first selection stage, the titles and abstracts of the selected studies were screened by both reviewers to select appropriate studies for full text screening. During the second stage, the full texts were assessed to abstract relevant evidence about the first three stages of the policy process. Because of limited time, the full-text screening was completed by TGK after a random sample of 20 articles (10%) had been screened by both reviewers to test and fine tune the eligibility criteria, as well as to ensure consensus.

The title and abstract screening criteria were as follows: an article should 1) be written in English, 2) have a full text available and 3) concern one of the three policies of interest (i.e., raising the age of sale, limiting the number or type of sale outlets and banning tobacco displays) or broader topics such as youth access/availability. A total of 138 articles were not related to any of the three selected policies, 15 articles had no full text available, and 9 articles were not written in English. We checked whether the non-English articles mainly focused on the first three stages of the policymaking process by reading the English abstracts, and concluded this was not the case. The remaining 200 articles were analyzed to determine whether they presented evidence on any of the first three stages of the policymaking process (see data extraction below) (Fig. 1)

.

Data extraction

Because this review is realist inspired, we followed the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) guidelines for data extraction and appraisal [41]. Both reviewers appraised the contribution of evidence in terms of both rigor and relevance. In terms of rigor (i.e., judging the credibility and trustworthiness of evidence), a dichotomy was made between “anecdotal evidence,” such as author accounts in the introduction and discussion sections (which could be considered “thin” evidence), and evidence resulting from scientific analyses employing a scientific method (which could be considered “thick” evidence). Evidence was considered relevant if it explicitly described a causal link between a certain determinant and the adoption one of the three selected policies (e.g., the enactment of a ban on vending machines in response to the federal Synar Amendment of the United States).

Subsequently, the 200 articles were assessed by the first author alone. Evidence was deemed relevant if it met the following eligibility criteria referring to the first three stages of the policy process: 1) agenda setting: the paper provides information on the process of acknowledging an issue as a policy problem 2) policy formulation: the paper provides information on the process of formulating a policy in response to a problem, and 3) policy legitimation: the paper provides information on the process of legitimating the choice for a specific type of policy. We further extracted the title of the article, the full names of the authors, the year of publication, the main focus of the article (“Agenda setting/policy formulation/legitimation”, “Enforcement/compliance”, “Effectiveness of policy”, “Industry misconduct” or “Other”) and the policy measure the evidence was related to (“Raising the age of Sale”, “Limiting number or type of tobacco outlets” or “Banning tobacco displays”).

Results

We found 74 pieces of evidence in 53 articles that were related to one or more of the three policy stages of interest. Fifty-two pieces of evidence were related to raising the age of sale, 15 were related to limiting the number or type of tobacco outlets, and 7 were related to banning tobacco displays. One article offered a systematic analysis of data, whereas the other 52 articles gave anecdotal author accounts. A summary of the findings for each policy can be found in Table 1. All evidence can be found in the Additional file 2.

Raising the age of sale

All evidence about the age-of-sale policies was anecdotal and found in articles that focused on a different topic than agenda setting, policy formulation and/or legitimation (Table 1). Thirty pieces of evidence were found in articles that had enforcement/compliance (n = 13) or effectiveness of the policy (n = 17) as the main focus. Much of this evidence was from papers on the implementation of the federal Synar Amendment of the United States, in which the authors commented on the adoption of age-of-sale policies by individual states in response to this amendment. Seventeen pieces of evidence about age-of-sale policies were found in articles with a main focus on industry misconduct, in which the authors commented on how the industry promoted voluntary agreements as alternative policy solutions. The authors referred to these agreements as ineffective by design and noted that they were intended to ward off more comprehensive and effective legislation.

Limiting the number or type of tobacco outlets

Fifteen pieces of evidence were found that concerned limiting the number or type of tobacco outlets. Again, no evidence was found in articles that had agenda setting, policy formulation and/or legitimation as the main focus. Most pieces of evidence focused on the enforcement of and compliance with the policy (n = 4) or the effectiveness of the policy (n = 5). The pieces of evidence were all anecdotal, meaning that they were not found in the results section of the article and were not based on a systematic analysis of data.

Banning tobacco displays

We found seven pieces of evidence related to banning tobacco displays. Five of these came from one paper [42]. This was the only article in our database that focused on the first stages of the policy cycle and that offered a systematic analysis of data concerning the policymaking process. These authors examined the adoption of display bans in two Australian jurisdictions. The empirical analysis showed how the ban was legitimized by framing it in terms of youth prevention and combining the ban with other policy measures, thus generating strong public support for these measures. Furthermore, presenting the ban as a natural extension of existing advertising bans increased its attractiveness to policymakers. Evidence was also presented regarding the agenda setting phase, which described how a widely accepted and highly compelling evidence base about tobacco control interventions in general created a favorable political environment. This environment enabled the passage of a tobacco display ban without an explicit prior analysis of scientific evidence in support of the ban [42]. The remaining two pieces of evidence were anecdotal and described the FCTC, endgame strategies, and their agenda setting functions.

Distribution across time

Figure 2 presents boxplots of the distribution across time of the publication of the identified pieces of evidence regarding the three policy measures. The evidence on the policy process of the two youth access policies was published prior to evidence on the policy process of the display bans.

Discussion

Our study showed that scientific, systematic evidence on the first stages of the policy process is scarce for the three policies under study. Most evidence was anecdotal, i.e., restricted to incidental observations presented as accounts of the authors. We were able to identify only one study that presented systematic scientific evidence on the policy process [42]. This study provided evidence on the agenda setting and legitimation phases of policy processes that ultimately resulted in the adoption of display bans in two Australian jurisdictions [42].

These findings support the general claim of Clavier & de Leeuw [30] that the policymaking process is understudied in the health promotion field, at least as far as youth prevention policies in the field of tobacco control are concerned. Scholars often study what happens after a policy has been adopted (e.g., the implementation, evaluation and policy maintenance stages). The predominance of this late-stage focus is further illustrated by our finding that most pieces of anecdotal evidence that we found regarding the early phases of the policy process were identified in papers that mainly focused on later stages of the process (e.g., implementation, evaluation and policy maintenance).

Why are the initial phases of the policy process understudied in research on policies to limit youth access and exposure to tobacco? The answer might be that public health scientists consider policymaking to be an abstract construct that is best left to the domain of politics [93]. De Leeuw et al. [93] remark that only a few health promotion scholars are trained in the political sciences. The interest of researchers trained in health promotion or public health may not lie in the “obscure” and hard-to-grasp process of policymaking [93]. Moreover, researchers who are trained in the behavioral or psychological sciences may be more inclined to study the behavior of individuals in response to a certain tobacco control policy. Tobacco control policies may then be merely considered distal determinants of health [93].

In describing the relationship between science and policymaking, Larsen [94] argues that the tobacco control research literature can be classified into two broad categories: a science-driven body and a policy-driven one. Research in the science-driven category often concludes that policymakers should base their policies on scientific findings, which are considered to be immediate and sufficient causes for the formulation of policies. Smith [95] makes a similar claim in the wider domain of public health policy by describing a “knowledge-driven model” in which research findings are assumed to provide the necessary pressure for policy to develop. Politics are then merely seen as a “barrier”, which science must overcome. The second body of tobacco control research, Larsen [94] claims, is smaller in size and regards scientific findings as one among many factors that influence policymakers’ decisions. This category typically focuses on the dynamics and institutional surroundings of public policy [94].

It seems that most literature that we found could be grouped into the first category (i.e., the science- or knowledge-driven body of literature), which is often reflected by normative comments in the discussion sections in which authors conclude that policymakers should consider scientific evidence about effectiveness to base policymaking decisions on. However, without rigorous scientific assessment of the first stages, it remains uncertain how the outcomes of studies on effectiveness, enforcement or compliance could be relevant to policymaking in these initial phases. Whereas advocates stress the importance of evidence in their work and define it as being central to their advocacy, politicians and political advisors may be more inclined to listen to economic and ideological arguments in governmental debates [96].

A possible limitation of this study was that, due to time and resource constraints, the full-text screening of the 200 articles was performed by one individual. Full-text screening by two individuals may have resulted in slightly more or fewer abstracted anecdotal pieces of evidence. However, the main conclusion of our study remains valid: there is only one article that focuses on the first three stages of the policy process.

If we want to understand the substantial variation in tobacco control policy adoption across different countries [97], we need to gain more insight into the first phases of the policy process. Many ideas circulate about what causes this variation in policy adoption; however, there is barely any scientific evidence on why policy processes have led to such different outcomes in different countries. Moreover, a better understanding of such processes may be of crucial importance for tobacco control advocates to work more effectively.

Conclusion

The processes influencing the adoption of youth access and exposure policies have been grossly understudied. We identified only one study that systematically examined the first stages of the policy process of tobacco display bans in two Australian jurisdictions. Aside from the evidence resulting from this study, which was based on a scientific analysis of data, all other evidence we found was merely anecdotal and restricted to author accounts. We therefore call on researchers to devote more attention to the initial phases of the policy process of youth prevention policies in tobacco control. Specifically, this means systematic empirical research that employs existing theories on the process of policymaking [33,34,35,36,37,38] and that utilizes, when possible, a comparative approach. A better understanding of these three first phases, as they are relevant to policy adoption, is essential to understand country variations in tobacco control policy and to help tobacco control advocates use the political arena more effectively.

Availability of data and materials

The generated dataset and search strategies are attached to the supplementary file.

Abbreviations

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- RAMESES:

-

Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards

- SSCI:

-

Social Sciences Citation Index

References

U.S. National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 21. NIH Publication No. 16-CA-8029A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2016.

World Health Organization. The European tobacco control report. Copenhagen: WHO regional office for Europe, 2007. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/68117/E89842.pdf (Accessed 6 July 2017).

Willemsen MC, de Zwart WM. The effectiveness of policy and health education strategies for reducing adolescent smoking: a review of the evidence. J Adolesc. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0254.

Richardson L, Hemsing N, Greaves L, et al. Preventing smoking in young people: a systematic review of the impact of access interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6041485.

Liang L, Chaloupka F, Nichter M, et al. Prices, policies and youth smoking. Addiction. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.7.x.

Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob control. 2000;9:47–63.

Nuyts PAW, Kuijpers TG, Willemsen MC, Kunst AE. How can a ban on tobacco sales to Minors be effective in changing smoking behaviour among youth? – A realist review. Prev Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.08.013.

Donaghy E, Bauld L, Eadie D, et al. A qualitative study of how young Scottish smokers living in disadvantaged communities get their cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt095.

Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Youth access interventions do not affect youth smoking. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1088–92.

DiFranza JR. Which interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors can be expected to reduce smoking? Tob Control. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050145.

Chapman S, Freeman B. Regulating the tobacco retail environment: beyond reducing sales to minors. Tob Control. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2009.031724.

Caceres L, Chaiton M. Hungary: state licensing for tobacco outlets. Tob Control. 2013;22:292–3.

Schneider JE, Reid RJ, Peterson NA, et al. Tobacco outlet density and demographics at the tract level of analysis in Iowa: implications for environmentally based prevention initiatives. Prev Sci. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-005-0016-z.

Adams ML, Jason LA, Pokorny S, et al. Exploration of the link between tobacco retailers in school neighborhoods and student smoking. J Sch Health. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12006.

Lipperman-Kreda S, Mair C, Grube JW, et al. Density and proximity of tobacco outlets to homes and schools: relations with youth cigarette smoking. Prev Sci. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121013-0442-2.

Shortt NK, Tisch C, Pearce J, et al. The density of tobacco retailers in home and school environments and relationship with adolescent smoking behaviours in Scotland. Tob Control. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051473.

Cohen JE, Anglin L. Outlet density: a new frontier for tobacco control. Addiction. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02389.x.

Myers AE, Hall MG, Isgett LF, et al. A comparison of three policy approaches for tobacco retailer reduction. Prev Med. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.025.

WHO. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2013: enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/ (Accessed 10 July 2017).

Robertson L, Marsh L, Hoek J, et al. Regulating the sale of tobacco in New Zealand: a qualitative analysis of retailers’ views and implications for advocacy. Int J Drug Policy. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.015.

Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntn002.

Robertson L, Cameron C, McGee R, et al. Point-of-sale tobacco promotion and youth smoking: a meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052586.

Li L, Borland R, Fong GT, et al. Impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Health Educ Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt058.

Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, et al. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu168.

Haw S, Amos A, Eadie D, et al. Determining the impact of smoking point of sale legislation among youth (Display) study: a protocol for an evaluation of public health policy. BMC Public Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-251.

Scheffels J, Lavik R. Out of sight, out of mind? Removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Norway. Tob Control. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052586.

Statens Institutt For Forbruksforskning. Evaluering av forbud mot synlig oppstilling av tobakksvarer. http://www.hioa.no/extension/hioa/design/hioa/images/sifo/files/file77487_rapport_tobakk_4_august_2011.pdf (Accessed 10 July 2017)

McNeill A, Lewis S, Quinn C, et al. Evaluation of the removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Ireland. Tob Control. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.038141.

Kuipers MA, Beard E, Hitchman SC, et al. Impact on smoking of England's 2012 partial tobacco point of sale display ban: a repeated cross-sectional national study. Tob control. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052724.

Clavier C, de Leeuw E. Health Promotion and the Policy Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Mackenbach J. Political determinants of health. Eur J Public Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt183.

Oliver TR. The politics of public health policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123126.

Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company; 1984.

Baumgartner FR, Jones BD. Policy dynamics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002.

Sabatier PA, Weible CM. The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Innovations and clarifications. In: Sabatier PA, editor. Theories of the Policy Process. 2nd ed. Boulder: Westview Press; 2016. p. 189–217.

Bache I, Flinders M. Multi-level Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Rose R. Lesson-drawing in public policy: A guide to learning across time and space. Chatham: Chatham House Publishers; 1993.

Dolowitz D, Greenwold S, Marsh D. Policy transfer: something old, something new, something borrowed, but why red, white and blue? Parliam Aff. 1999;52(4):719–30.

Cairney P. Understanding public policy: Theories and issues. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012.

Asbridge M. Public place restrictions on smoking in Canada: Assessing the role of the state, media, science and public health advocacy. Soc Sci Med. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S02779536(03)00154-0.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(5):1005–22.

Cenko C, Pulvirenti M. Politics of Evidence: The Communication of Evidence by “Stakeholders” when Advocating for Tobacco Point-of-sale Display Bans in Australia. Aust J Public Adm. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12138.

Asumda F, Jordan L. Minority youth access to tobacco: a neighborhood analysis of underage tobacco sales. Health Place. England. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.03.006.

Chandora R, Song Y, Chaussard M, Palipudi KM, Lee KA, Ramanandraibe N, et al. Youth access to cigarettes in six sub-Saharan African countries. Prev Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.01.018.

Cummings KM, Pechacek T, Shopland D. The Illegal Sale of Cigarettes to United-States Minors - Estimates by State. Am J Public Health. 1994. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.84.2.300.

Gilpin EA, Lee L, Pierce JP. Does adolescent perception of difficulty in getting cigarettes deter experimentation? Prev Med. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.001.

Gratias EJ, Krowchuk DP, Lawless MR, Durant RH. Middle school students’ sources of acquiring cigarettes and requests for proof of age. J Adolesc Health. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00019-1.

Grucza RA, Plunk AD, Hipp PR, Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss MJ, Brownson RC, et al. Long-term effects of laws governing youth access to tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2013. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301123.

Jacobson PD, Wasserman J. The implementation and enforcement of tobacco control laws: Policy implications for activists and the industry. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-24-3-567.

Kirchner TR, Villanti AC, Cantrell J, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Ganz O, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco retail outlet advertising practices and proximity to schools, parks and public housing affect Synar underage sales violations in Washington, DC. Tob Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051239.

Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Validity of assessments of youth access to tobacco: the familiarity effect. Am J Public Health. 2003. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.11.1883.

Levy DT, Chaloupka F, Slater S. Expert opinions on optimal enforcement of minimum purchase age laws for tobacco. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1097/00124784-200,006,030-00015.

Sundh M, Hagquist C. Compliance with a minimum-age law of 18 for the purchase of tobacco--the case of Sweden. Health Educ Res. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl007.

Weinbaum Z, Quinn V, Rogers T, Roeseler A. Store tobacco policies: a survey of store managers, California, 1996–1997. Tob Control. 1999;8:306–10.

White MM, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, Pierce JP. Facilitating adolescent smoking: who provides the cigarettes? Am J Health Promot. 2005. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.355.

Forster JL, Hourigan ME, Kelder S. Locking devices on cigarette vending machines: evaluation of a city ordinance. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1217–9.

Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Internet cigarette vendor compliance with credit card payment and shipping bans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt159.

Alciati MH, Frosh M, Green SB, Brownson RC, Fisher PH, Hobart R, et al. State laws on youth access to tobacco in the United States: measuring their extensiveness with a new rating system. Tob Control. 1998;7:345–52.

Botello-Harbaum MT, Haynie DL, Iannotti RJ, Wang J, Gase L, Simons-Morton B. Tobacco control policy and adolescent cigarette smoking status in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp081.

Brownson RC, Koffman DM, Novotny TE, Hughes RG, Eriksen MP. Environmental and policy interventions to control tobacco use and prevent cardiovascular disease. Health Educ Q. 1995;22:478–98.

Forster JL, Widome R, Bernat DH. Policy interventions and surveillance as strategies to prevent tobacco use in adolescents and young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.014.

Forster JL, Wolfson M. Youth access to tobacco: policies and politics. Annu Rev. Public Health. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.203.

Hagquist C, Sundh M, Eriksson C. Smoking habits before and after the introduction of a minimum-age law for tobacco purchase: analysis of data on adolescents from three regions of Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940701256925.

Liang L, Chaloupka F, Nichter M, Clayton R. Prices, policies and youth smoking, May 2001. Addiction. 2003;98:105–22.

Millett C, Lee JT, Gibbons DC, Glantz SA. Increasing the age for the legal purchase of tobacco in England: impacts on socio-economic disparities in youth smoking. Thorax. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.154963.

Morain SR, Winickoff JP, Mello MM. Have tobacco 21 laws come of age? N Engl J Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1603294.

Rimpelä AH, Rainio SU. The effectiveness of tobacco sales ban to minors: the case of Finland. Tob Control. 2004;13:167–74.

Shelton DM, Alciati MH, Chang MM, Fishman JA, Fues LA, Michaels J, et al. State laws on tobacco control--United States, 1995. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1995;44:1–28.

Spivak AL, Monnat SM. Prohibiting juvenile access to tobacco: Violation rates, cigarette sales, and youth smoking. Int J Drug Policy. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.03.006.

Tauras JA. Differential impact of state tobacco control policies among race and ethnic groups. Addiction. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01960.x.

Conley Thomson C, Hamilton WL, Siegel MB, Biener L, Rigotti NA. Effect of local youth-access regulations on progression to established smoking among youths in Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2006.018002.

Kanda H, Osaki Y, Ohida T, Kaneita Y, Munezawa T. Age verification cards fail to fully prevent minors from accessing tobacco products. Tob Control. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.036947.

Ribisl KM, Williams RS, Gizlice Z, Herring AH. Effectiveness of state and federal government agreements with major credit card and shipping companies to block illegal Internet cigarette sales. PLoS One. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016754.g002.

Schneider S, Meyer C, Yamamoto S, Solle D. Implementation of electronic locking devices for adolescents at German tobacco vending machines: intended and unintended changes of supply and demand. Tob Control. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2008.028035.

Robertson L, Cameron C, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J. Point-of-sale tobacco promotion and youth smoking: a meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052586.

Apollonio DE, Malone RE. The “We Card” program: tobacco industry “youth smoking prevention” as industry self-preservation. Am J Public Health. 2010. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.169573.

Barraclough S, Morrow M. A grim contradiction: the practice and consequences of corporate social responsibility by British American Tobacco in Malaysia. Soc Sci Med. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.001.

Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0.

Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C, Sheron N, Neal B, Thamarangsi T, et al. Profits and pandemics: Prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3.

Mosher JF. The merchants, not the customers: resisting the alcohol and tobacco industries’ strategy to blame young people for illegal alcohol and tobacco sales. J Public Health Policy. 1995;16:412–32.

Nagler RH, Viswanath K. Implementation and research priorities for FCTC Articles 13 and 16: tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship and sales to and by minors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts331.

Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Attempts to undermine tobacco control: tobacco industry “youth smoking prevention” programs to undermine meaningful tobacco control in Latin America. Am J Public Health. 2007. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.094128.

Sharma LL, Teret SP, Brownell KD. The food industry and self-regulation: standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. Am J Public Health. 2010. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.

Wakefield M, McLeod K, Perry CL. “Stay away from them until you’re old enough to make a decision”: tobacco company testimony about youth smoking initiation. Tob Control. 2006; doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2005.011536

Difranza JR, Savageau JA, Aisquith BF. Youth access to tobacco: The effects of age, gender, vending machine locks, and “it’s the law” programs. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:221–4.

Bailey WJ, Crowe JW. A national survey of public support for restrictions on youth access to tobacco. J Sch Health. 1994. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb03318.x.

Emmons KM, Kawachi I, Barclay G. Tobacco control: a brief review of its history and prospects for the future. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70425-1.

Gottlieb NH, Goldstein AO, Flynn BS, Cohen EJE, Bauman KE, Solomon LJ, et al. State legislators’ beliefs about legislation that restricts youth access to tobacco products. Health Educ Behav. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198102251033.

Mamudu HM, Veeranki SP, John RM. Tobacco use among school-going adolescents (11–17 years) in Ghana. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts269.

Chriqui JF, Ribisl KM, Wallace RM, Williams RS, O’Connor JC, el Arculli R. A comprehensive review of state laws governing Internet and other delivery sales of cigarettes in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200701838232.

Schneider S, Gruber J, Yamamoto S, Weidmann C. What Happens After the Implementation of Electronic Locking Devices for Adolescents at Cigarette Vending Machines? A Natural Longitudinal Experiment From 2005 to 2009 in Germany. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr067.

Whyte G, Gendall P, Hoek J. Advancing the retail endgame: public perceptions of retail policy interventions. Tob Control. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051065.

de Leeuw E, Clavier C, Breton E. Health policy – Why Research It and How: Health Political Science. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-12-55.

Larsen LT. The political impact of science: is tobacco control science-or policy-driven? Science Public Policy. 2008. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234208X394697.

Smith K. Beyond Evidence-based Policy in Public Health: The Interplay of Ideas. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013.

Chapman S. Public health advocacy and tobacco control: making smoking history. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing ltd; 2008.

Marmor TR, Lieberman ES. Tobacco control in comparative perspective: eight nations in search of an explanation. In: Feldman ES, Bayer R, editors. Unfiltered Conflicts over Tobacco policy public and Public Health. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2004. p. 275–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Paulien Nuyts for helping with the two-stage screening and librarian Gregor Franssen for helping formulate the search strategy.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission as part of the SILNE-R project under Grant number 635056. The funding body was not in any way involved in design of the study, data collection, analyses, interpretation of data nor writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AEK and MCW designed the study, TGK performed the literature searches, collected and processed the data. With the help of MCW and AEK, TGK analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Thomas G Kuijpers is a PhD student at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences at Maastricht University. Anton E Kunst is professor in Social Epidemiology and Head of Department of Public Health at Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam. Marc C Willemsen is professor in Tobacco Control at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences at Maastricht University and head of The Netherlands Expertise Center for Tobacco Control (NET) at the Trimbos Institute.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required for this study because no human or animal subjects were involved.

Consent for publication

No consent for publication was required for this study because no human subjects were involved.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategies. (DOC 27 kb)

Additional file 2:

Extracted evidence. (DOC 191 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuijpers, T.G., Kunst, A.E. & Willemsen, M.C. Policies that limit youth access and exposure to tobacco: a scientific neglect of the first stages of the policy process. BMC Public Health 19, 825 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7073-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7073-x