Abstract

Background

Over the last decade, the Kenyan HIV treatment program has grown exponentially, with improved survival among people living with HIV (PLHIV). In the same period, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have become a leading contributor to disease burden. We sought to characterize the burden of four major NCDs (cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes mellitus) among adult PLHIV in Kenya.

Methods

We conducted a nationally representative retrospective medical chart review of HIV-infected adults aged ≥15 years enrolled in HIV care in Kenya from October 1, 2003 through September 30, 2013. We estimated proportions of four NCD categories among PLHIV at enrollment into HIV care, and during subsequent HIV care visits. We compared proportions and assessed distributions of co-morbidities using the Chi-Square test. We calculated NCD incidence rates and their confidence intervals in assessing cofactors for developing NCDs.

Results

We analyzed 3170 records of HIV-infected patients; 2115 (66.3%) were from women. Slightly over half (51.1%) of patient records were from PLHIVs aged above 35 years. Close to two-thirds (63.9%) of PLHIVs were on ART. Proportion of any documented NCD among PLHIV was 11.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 9.3, 14.1), with elevated blood pressure as the most common NCD 343 (87.5%) among PLHIV with a diagnosed NCD. Despite this observation, only 17 (4.9%) patients had a corresponding documented diagnosis of hypertension in their medical record. Overall NCD incidence rates for men and women were (42.3 per 1000 person years [95% CI 35.8, 50.1] and 31.6 [95% CI 27.7, 36.1], respectively. Compared to women, the incidence rate ratio for men developing an NCD was 1.3 [95% CI 1.1, 1.7], p = 0.0082). No differences in NCD incidence rates were seen by marital or employment status. At one year of follow up 43.8% of PLHIV not on ART had been diagnosed with an NCD compared to 3.7% of patients on ART; at five years the proportions with a diagnosed NCD were 88.8 and 39.2% (p < 0.001), respectively.

Conclusions

PLHIV in Kenya have a high prevalence of NCD diagnoses. In the absence of systematic, effective screening, NCD burden is likely underestimated in this population. Systematic screening and treatment for NCDs using standard guidelines should be integrated into HIV care and treatment programs in sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The last decade has witnessed an unprecedented growth in coverage of HIV care and treatment programs globally. Expanded criteria for initiation of highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV (PLHIV) has been associated with increased longevity and favorable treatment outcomes [1, 2]. Over the same period, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and associated deaths have risen steadily. At a global scale, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 41 million NCD-related deaths occur on an annual basis [3]. Three quarters of these deaths are in low and middle-income countries. In the general population, four major NCDs - cardiovascular diseases (including hypertension, heart attack and stroke), cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes mellitus make the largest contribution to both morbidity and mortality [4].

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which is home to over half of the estimated PLHIV worldwide, is faced with a dual disease epidemic – communicable diseases and NCDs [5,6,7]. While several countries in SSA continue to report rapid scale-up of their national ART programs [1, 7, 8], a concomitant rise in incidence of NCDs and NCD-related deaths has also been observed over the last decade [9]. NCDs, and particularly the four aforementioned, account for over half of all hospital admissions and deaths in Kenya [6, 10]. Increased longevity of PLHIV on ART suggests likely increases in prevalence of NCDs among PLHIV in the future [1, 7, 8, 11, 12].

The burden and impact of NCDs among PLHIV in lower and middle income countries with robust ART programs is still not clearly defined [13]. Several studies examining NCDs among PLHIV have been conducted in SSA [14,15,16,17,18]. Most of these have involved cross-sectional surveys of facility level data, with smaller and less-representative samples. Previous national HIV treatment outcome studies in SSA have also not addressed NCDs among PLHIV [8, 19]. Additionally, there is paucity of data on the impact of noncommunicable disease burden among PLHIV from early public health approaches in HIV programming that stratified clients in care based on declining CD4 counts [20]. PLHIV in care with low CD4 counts as per prevailing national guidelines were considered eligible for HIV treatment and had ART included in their care; accordingly these “ART cohorts” were different from the corresponding clients in “pre-ART cohorts” who had higher CD4 counts than the then established thresholds for ART initiation.

Using a nationally representative sample, we sought to estimate the burden of NCDs among PLHIV enrolled in HIV care and treatment in Kenya between 2003 and 2013.

Methods

Study design and population

The second Longitudinal Surveillance of Treatment in Kenya (LSTIK II) was a retrospective cohort study of HIV-infected patients aged ≥15 years in Kenya, who enrolled into HIV care between October 1, 2003, and September 30, 2013. Study participants were sampled from a nationally representative random sample of 50 facilities offering ART services that had been in operation for a minimum of 15 months, and supporting at least 50 patients aged ≥15 years on ART according to the 2013 NASCOP Annual Progress Report. Our analysis was based on the cohort of patients who were enrolled in HIV care during the study period (“pre-ART cohort”), some of whom started ART in the follow-up interval between enrollment in care and data abstraction. All patients had at least 12 months of clinical follow-up prior to chart abstraction.

During the study period, there were three time periods with different ART initiation thresholds: 1st January 2003 to 31st December 2005 when the threshold for ART initiation was CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3; 1st Jan 2006 to 30th June 2010 when the threshold for ART initiation increased to CD4 < 250 cells/mm3; and 1st July 2010 to 30th September 2013 when the threshold was further increased to CD4 < 350 cells/mm3 [21,22,23].

Data collection methods

Medical records were abstracted during October 2015 –September 2016 using a standard tool on netbook computers (Mirus Innovations, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Data were securely transmitted electronically to a central database in Nairobi. Data cleaning and analyses were carried out using Stata 14.2 (Stata Corporation, Texas USA).

Measures

We described and restricted our analysis of co-morbidities to four major NCD categories - cardiovascular diseases (including hypertension, heart attack and stroke), cancer, chronic respiratory diseases (including asthma) and diabetes mellitus. These four categories are associated with over 60% of all NCD-related deaths. NCDs were measured based on documentation of any of these diagnoses at enrollment into HIV care or during the patient follow-up period. Blood pressure readings were recorded from charts. Two or more measures taken within 12 months of systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg were defined as elevated blood pressure. The elevated blood pressure criteria were considered to be closely aligned with a clinical diagnosis of hypertension that involves multiple elevated blood pressure readings and consistent with Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8, 2014) recommended threshold for pharmacologic treatment of hypertension of persons aged < 60 years [24].

We conducted our analysis based on the three periods of changing CD4 count thresholds for ART initiation described above. ART drugs that constituted first line regimens among adults changed over the guideline review periods and included stavudine (d4T), zidovudine (AZT), abacavir (ABC) and tenofovir (TDF). Regimens that included lopinavir (LPV/r) were considered second line.

Statistical analysis

We estimated proportions of NCDs among PLHIV at enrollment into HIV care, and during subsequent follow-up visits. We compared proportions and assessed distributions of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by sex using Wald adjusted Pearson’s Chi- Square test. We used the Cox regression-based test for equality of survival curves by ART status and tested for proportional-hazards assumption. We assessed for differences in failure rates using weighted survival curves, adjusting for age at enrollment. Data were survey-set before analyses. Data were assumed to be missing at random; we did not impute the data. The percentages with an NCD were weighted to account for sampling. All estimates were adjusted to account for sampling design and missing data. Analyses were carried out in Stata 14.2 (Stata Corporation, Texas USA).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s Scientific and Ethics Review Unit, the Kenyatta National Hospital, University of Nairobi Ethics Review Committee as part of a nested study and by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco. This study was reviewed according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) human research protection procedures and was determined to be and approved as research.

Results

Study population characteristics

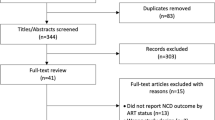

A total of 3170 patient records were analyzed (Fig. 1), with over two thirds of records (2115) constituting women. At the time of data abstraction, slightly over half (52.1%) of patients were aged < 35 years; women were more likely to be in this younger age group (p < 0.001). The majority (68.3%) of patients were employed; men were more likely to be in formal or informal employment than women (p < 0.001). Half (51.1%) of patients were married or cohabiting, 12% were widowed, 7.8% divorced/separated, and 13.5% single or never married. There was a significant difference in marital status between men and women (p < 0.001); 64.7% (95% CI: 55.9, 72.7) of men were married compared to 44.2% (95% CI: 39.9, 48.7), of women (Table 1).

In this cohort, 63.9% of patients had initiated ART by the time of data abstraction, with no significant differences by sex (p = 0.874). Just over half of the patients in the cohort had been initially enrolled in care during 01 January 2006 to 30 June 2010 (54.3%); only 9% had been enrolled during the 01 Jan 2003 to 31 Dec 2005 guideline period. No differences were observed by sex across the three guideline enrollment periods (p = 0.070). Similar proportions of patients were on d4T and TDF containing regimens, (36.5% [95% CI: 31.8, 41.5] vs 35.8% [95% CI: 30.7, 41.1], respectively). A quarter of the patients (26.9%) had been on an AZT containing regimen. Only 0.4 and 0.5% of patients were on a LPV/r or ABC containing regimen respectively at the time of data abstraction. No significant difference was noted in regimen type between men and women (p = 0.05). Most patients did not have a documented WHO stage (74.7%) or CD4 count (85.4%) (Table 1).

NCDs among PLHIV

In this cohort, 387/3170 (weighted percentage of 11.5%) (95% CI: 9.3, 14.1), had evidence of any NCD in their HIV clinical care record. No difference between the proportion of men and women with an NCD (p = 0.308) was observed (Table 1).

The proportion of patients with a documented diagnosis of an NCD among PLHIV not on ART rose sharply in the first few years of follow-up compared to the otherwise gentle trajectory and longer duration observed for PLHIV on ART (p < 0.001). PLHIV who had not yet initiated ART were more likely to have an NCD diagnosis at one and five years of follow up. At one year of follow up 43.8% of PLHIV not on ART had been diagnosed with an NCD compared to 3.7% of patients on ART; at five years the proportions with a diagnosed NCD were 88.8 and 39.2% (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2).

Overall NCD incidence was 35.1 per 1000 person years. Men had an overall NCD incidence of 42.3 per 1000 person years (95%CI: 35.8, 50.1) compared to 31.6 (95%CI: 27.7, 36.1) in women. The highest incidence rates were observed among 45–54 and ≥ 55 year olds at 57.5 (95%CI: 46.7, 70.9) and 55.0 (95%CI: 38.5, 78.7) per 1000 person years respectively. The 15–24 year age band had the lowest incidence rate at 21.0 per 1000 person years (95%CI: 13.8, 31.9). No significant differences in NCD incidence rates were seen based on marital or employment status, (Table 2).

Among the 387 PLHIV with an NCD, the crude incidence rate ratio (crude IRR) for development of NCDs during follow up was 2.47 (95%CI: 1.6, 3.6) for PLHIV not initiated ART as compared with PLHIV who had initiated ART [p < 0.001]), (Fig. 3). Crude IRR for NCDs among men was similar to that among women (IRR = 1.02, p = 0.84). There was no difference in NCD crude IRR between PLHIV aged < 35 years compared to PLHIV aged ≥35 years (p = 0.51). No difference was detected between single/never married PLHIV and those who were married/cohabiting (IRR = 1.08, p = 0.62). Similarly, crude IRR of developing NCDs was no different among PLHIV who were not employed during follow up versus PLHIV who were employed (IRR = 1.29, p = 0.08). WHO staging comparing advanced disease staging (stage III/IV) to early disease staging (stage I/II) had a crude IRR of 0.85 (p = 0.5). Age-adjusted analysis revealed no further effect for all IRRs previously described.

NCDs burden

Cardiovascular disease

We found that among PLHIV with any recorded NCD, 347/387, weighted percentage of 88.9% (95%CI 81.5, 93.5) were found to have a documented record of any cardiovascular disease (CVD) including hypertension. CVD was more frequent in persons on ART 93.9% (95%CI 90.0, 96.3) vs 53.9% (95%CI 30.7, 75.6) not on ART respectively (p = 0.03), (Table 3). Most identified cases of CVD were associated with elevated blood pressure.

Elevated blood pressure

Among PLHIV with any recorded NCD, 343/387, weighted percentage of 87.5% (95%CI 80.1, 92.4) were found to have two or more elevated blood pressure readings taken < 12 months apart (our proxy measure of hypertension). Among patients with an NCD comorbidity, elevated blood pressure was more frequent in persons on ART 92.8% (95%CI 88.9, 95.4) vs 50.6% (95%CI 26.5, 74.5) not on ART respectively (p = 0.03), (Table 3). Although serial elevated blood pressures were detected among 343 patients, only 17 (0.5%) had a documented diagnosis of hypertension in their medical record (results not shown).

Diabetes mellitus

Only 9/387, a weighted percentage of 2.1% (95%CI: 0.9, 4.7) of PLHIV with NCD had documented diabetes mellitus. Compared by ART status, no significant difference was observed between PLHIV on ART and those not on ART, (p = 0.44) (Table 3).

Chronic respiratory diseases

We found 9/387, a weighted percentage of 2.3% (95%CI 1.1, 4.9) of PLHIV with NCD had a documented diagnosis of asthma. Compared to patients on ART, there was no difference in documented asthma among non-ART patients; 1.3% (95%CI 0.5, 3.4) vs 9.3% (95%CI 3.2, 24.5) respectively, (p = 0.15) (Table 3).

Cancer

Any form of cancer was documented among 3/387, weighted percentage of 1.1% (95%CI 0.2, 4.8) of PLHIV with NCD with no statistical difference between patients on ART 1.2% (95%CI 0.2, 5.6) and those not on ART 0%, (p = 0.28) (Table 3).

Discussion

This evaluation describes the burden of NCDs among HIV patients from a nationally representative survey of HIV care and treatment in Kenya prior to the national implementation of ART for all PLHIV irrespective of CD4 count. This evaluation was conducted in the context of a rising burden of NCDs in Africa and a rapid scale up of antiretroviral therapy coverage that has contributed to increased life expectancy among PLHIV [2, 14, 25,26,27]. In this study overall incidence rates for diagnosed NCDs were lower amongst those on ART compared to those not on ART. It is possible that this can be attributed to differences in health seeking behaviors, health care access, or socioeconomic or other factors associated with delayed initiation of ART. This finding is consistent with other studies that have shown increased prevalence of NCD risk factors among PLHIV not on antiretroviral treatment [28, 29]. Compared to other studies that suggest social economic deprivation as a predictor of NCDs risk factors among PLHIV [18, 30], our study did not detect a difference based on employment status.

The WHO’s recommendation to expand ART eligibility to all persons diagnosed with HIV was adopted in Kenya in 2016 [31]. Clinical parameters of WHO stage and baseline CD4 have previously been associated with NCD risk [32]. In our study, WHO staging and baseline CD4 showed no significant associations with NCDs risk, although documentation was incomplete.

In other countries, an increased risk of developing NCDs in PLHIV has been associated with exposure to certain ART drugs like stavudine, efavirenz and protease inhibitors [33,34,35,36]. A meta-analysis showed that exposure to ART drugs independently increases risk of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases [37]. However, our study and a study conducted in Zimbabwe conducted found no significant association between either ART drug class or duration of exposure and NCDs [14]. This discrepancy may result from limitations in detecting NCDs in our study, specific ARTs in use during this study period, or differences between populations.

The convergence of a dual burden of NCDs and communicable diseases in SSA is not in question [2, 6, 17, 27]. The burden of hypertension and cardiovascular disease regardless of HIV status remains substantial [38, 39]. Several studies have shown evidence of increased blood pressure and hypertension among PLHIVs on ART; an indication that a distinct difference exists in the characterization of cardiovascular disease between PLHIVs and non-PLHIVs [37, 40].

By using two elevated blood pressure readings within a 12 month interval (as a proxy for hypertension), our study found elevated blood pressure to be the most common (87.5%) among the 4 selected NCDs in our study population. In comparison, only 0.5% of these patients had a recorded diagnosis of hypertension. This discrepancy highlights the need for systematic screening NCDs in this population. The population of PLHIV in care that had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus was comparable to that of the general population with raised blood glucose (2.1% vs 1%) [10]. Our study findings are similar to those of several studies and population based NCDs surveys in SSA [10, 15, 38]. There is a need to emphasize cardiovascular and metabolic risk factor assessment at all clinical visits, especially for PLHIV in older age groups [6, 13, 17, 41].

Our study found a lower prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases, including asthma, among PLHIV enrolled in care when compared to estimates for the general population derived from a separate national survey of NCDs (2.3% vs 8.5%) [10]. Although noted to be a lower prevalence, deliberate screening for findings and risk factors associated with chronic respiratory conditions such as smoking and occupational hazards should be incorporated in routine screening [42]. Of note, most facilities did not perform spirometry for respiratory disease evaluation.

Cancers are the second largest cause of NCD-related deaths and account for 7% of overall mortality in Kenya [6]. In our study, the prevalence of cancer among PLHIV enrolled in care was 1.1%. In an era of increased access to ART, systematic reviews among PLHIV indicate steadily declining rates of AIDS defining malignancies among PLHIV with most cancer diagnoses now being pre-cancerous [40]. Screening of cancers, such as cervical cancer, however remains important and cost-effective when integrated into HIV care and treatment [31, 43].

The study data were abstracted from HIV care facility clinical records. The absence of standard processes, guidelines, and diagnostic tools for screening and testing for NCDs at HIV care facilities resulted in our survey underestimating NCD burden. Data for all NCD categories, except for elevated blood pressure, were identified through documentation of diagnoses in clinic records. Notably, the majority of patients who were classified as having an NCD in this survey were identified through review of serial blood pressure measurements, and not through a documented history of hypertension in the medical record. Additionally, patients with conditions associated with high mortality such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and severe heart failure may be less likely to be identified through clinic records, either not reaching initial care or being lost-follow-up prior to diagnosis. The high proportion of patients lost to follow up in this cohort likely also resulted in an underestimated of NCD burden. The retrospective design of our study limited our analysis of risk factors for NCDs among PLHIV that would have bolstered our study findings and allowed us to make robust comparisons to other nationwide NCD surveys [44].

Conclusions

We identified a high prevalence of NCDs among PLHIVs in Kenya that likely represents a substantial underdiagnoses of these categories of NCDs. Systematic screening and treatment for NCDs using standard guidelines should be integrated into HIV care and treatment programs in sub-Saharan Africa [2, 27]. Knowledge of NCDs burden could be improved through surveillance mechanisms and registries [45]. As Kenya seeks to reach the ambitious UNAIDS 90–90-90 goals through expanded treatment, strategies need to be developed that ensure health gains for PLHIVs are not eroded by a rising burden of NCD morbidity and mortality.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Abacavir

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- AZT:

-

Zidovudine

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- d4T:

-

Stavudine

- LPV/r:

-

Lopinavir/Ritanovir

- LSTIK:

-

Longitudinal Surveillance of Treatment in Kenya

- NASCOP:

-

National AIDS and STI Control Program

- NCD:

-

Noncommunicable disease

- PLHIV:

-

People living with HIV

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TDF:

-

Tenofovir

- UCSF:

-

University of California, San Francisco

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection Recommendations for a public health approach - Second edition. 2016.

El-Sadr WM, Goosby E. Building on the HIV platform: tackling the challenge of noncommunicable diseases among persons living with HIV. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32:S1–3.

WHO. Global Health Observatory Data. NCD mortality and morbidity. 2018 [Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en/.

WHO. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020. 2013.

Levitt NS, Steyn K, Dave J, Bradshaw D. Chronic noncommunicable diseases and HIV-AIDS on a collision course: relevance for health care delivery, particularly in low-resource settings - insights from South Africa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1690S–6S.

Ministry of Health. Kenya National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2015-2020. 2015.

UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2016.

Farahani M, Vable A, Lebelonyane R, Seipone K, Anderson M, Avalos A, et al. Outcomes of the Botswana national HIV/AIDS treatment programme from 2002 to 2010: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(1):e44–50.

Miszkurka M, Haddad S, Langlois EV, Freeman EE, Kouanda S, Zunzunegui MV. Heavy burden of non-communicable diseases at early age and gender disparities in an adult population of Burkina Faso: world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:24.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health Kenya, World Health Organization. Kenya STEPwise Survey for Non Communicable Diseases Risk Factors 2015 Report. 2015.

National AIDS Control council (NACC), National AIDS/STD control Programme (NASCOP). Kenya HIV Estimates 2015. 2016.

Bloomfield GS, Khazanie P, Morris A, Rabadan-Diehl C, Benjamin LA, Murdoch D, et al. HIV and noncommunicable cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases in low- and middle-income countries in the ART era: what we know and best directions for future research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2014;67 Suppl 1:S40–53.

Narayan KM, Miotti PG, Anand NP, Kline LM, Harmston C, Gulakowski R 3rd, et al. HIV and noncommunicable disease comorbidities in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a vital agenda for research in low- and middle-income country settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2014;67 Suppl 1:S2–7.

Magodoro IM, Esterhuizen TM, Chivese T. A cross-sectional, facility based study of comorbid non-communicable diseases among adults living with HIV infection in Zimbabwe. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:379.

Kavishe B, Biraro S, Baisley K, Vanobberghen F, Kapiga S, Munderi P, et al. High prevalence of hypertension and of risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs): a population based cross-sectional survey of NCDS and HIV infection in northwestern Tanzania and southern Uganda. BMC Med. 2015;13:126.

Edwards JK, Bygrave H, Van den Bergh R, Kizito W, Cheti E, Kosgei RJ, et al. HIV with non-communicable diseases in primary care in Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya: characteristics and outcomes 2010-2013. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109(7):440–6.

Peck RN, Shedafa R, Kalluvya S, Downs JA, Todd J, Suthanthiran M, et al. Hypertension, kidney disease, HIV and antiretroviral therapy among Tanzanian adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2014;12:125.

Kagaruki GB, Mayige MT, Ngadaya ES, Kimaro GD, Kalinga AK, Kilale AM, et al. Magnitude and risk factors of non-communicable diseases among people living with HIV in Tanzania: a cross sectional study from Mbeya and Dar Es Salaam regions. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:904.

Mutasa-Apollo T, Shiraishi RW, Takarinda KC, Dzangare J, Mugurungi O, Murungu J, et al. Patient retention, clinical outcomes and attrition-associated factors of HIV-infected patients enrolled in Zimbabwe's National Antiretroviral Therapy Programme, 2007-2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86305.

WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on the use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing Hiv Infection Recommendations For A Public Health Approach. 2013.

Ministry of Health GoK. Guidelines to Antiretroviral Drug Therapy in Kenya. 2001.

Ministry of Health GoK. Guidelines for Antiretroviral Drug Therapy in Kenya. 3rd ed2005.

Ministry of Health GoK. Guidelines for Antiretroviral therapy in Kenya. 4th ed2011.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint National Committee (JNC 8). Jama. 2014;311(5):507–20.

May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Orkin C, Kegg S, et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England). 2014;28(8):1193–202.

Trickey A, May MT, Vehreschild J-J, Obel N, Gill MJ, Crane HM, et al. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 And 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 4(8):e349–e56.

Vorkoper S, Kupfer LE, Anand N, Patel P, Beecroft B, Tierney WM, et al. Building on the HIV chronic care platform to address noncommunicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: a research agenda. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32:S107–S13.

van Heerden A, Barnabas RV, Norris SA, Micklesfield LK, van Rooyen H, Celum C. High prevalence of HIV and non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factors in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(2). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jia2.25012.

Patel P, Rose CE, Collins PY, Nuche-Berenguer B, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Peprah E, et al. Noncommunicable diseases among HIV-infected persons in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32:S5–S20.

Zolopa A, Andersen J, Powderly W, Sanchez A, Sanne I, Suckow C, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5575.

Ministry of Health National AIDS & STI Control Programme. Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection in Kenya 2016.

Tripathi A, Liese AD, Jerrell JM, Zhang J, Rizvi AA, Albrecht H, et al. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort of HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected persons: the impact of clinical and therapeutic factors over time. Diabet Med. 2014;31(10):1185–93.

Rasmussen LD, Mathiesen ER, Kronborg G, Pedersen C, Gerstoft J, Obel N. Risk of diabetes mellitus in persons with and without HIV: a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44575.

Oni T, Youngblood E, Boulle A, McGrath N, Wilkinson RJ, Levitt NS. Patterns of HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease multi-morbidity in peri-urban South Africa- a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:20.

Dave JA, Lambert EV, Badri M, West S, Maartens G, Levitt NS. Effect of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy on dysglycemia and insulin sensitivity in South African HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2011;57(4):284–9.

Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cole SR, Levine AM, Cohen M, DeHovitz J, et al. Antiretroviral therapy exposure and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the Women's Interagency HIV Study. AIDS (London, England). 2007;21(13):1739–45.

Nduka CU, Stranges S, Sarki AM, Kimani PK, Uthman OA. Evidence of increased blood pressure and hypertension risk among people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30(6):355–62.

Kwarisiima D, Balzer L, Heller D, Kotwani P, Chamie G, Clark T, et al. Population-based assessment of hypertension epidemiology and risk factors among HIV-positive and general populations in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156309.

Rabkin M, Palma A, McNairy ML, Gachuhi AB, Simelane S, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, et al. Integrating cardiovascular disease risk factor screening into HIV services in Swaziland: lessons from an implementation science study. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32:S43–S6.

Haregu TN, Oldenburg B, Sestwe G, Elliott J, Nanayakkara V. Epidemiology of Comorbidity of HIV/AIDS and Non-communicable Diseases in Developing Countries: A systematic review. J Glob Health Care Syst. 2012;2(1).

Sander LD, Newell K, Ssebbowa P, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Gray RH, et al. Hypertension, cardiovascular risk factors and antihypertensive medication utilisation among HIV-infected individuals in Rakai, Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(3):391–6.

Juma K, Reid M, Roy M, Vorkoper S, Temu TM, Levitt NS, et al. From HIV prevention to non-communicable disease health promotion efforts in sub-Saharan Africa: A Narrative Review. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32:S63–73.

Hyle EP, Naidoo K, Su AE, El-Sadr WM, Freedberg KA. HIV, tuberculosis, and noncommunicable diseases: what is known about the costs, effects, and cost-effectiveness of integrated care? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2014;67 Suppl 1:S87–95.

Petersen M, Yiannoutsos CT, Justice A, Egger M. Observational research on NCDs in HIV-positive populations: conceptual and methodological considerations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(Suppl. 1):S8–S16.

Patel P, Speight C, Maida A, Loustalot F, Giles D, Phiri S, et al. Integrating HIV and hypertension management in low-resource settings: lessons from Malawi. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002523.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This project publication has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of cooperative agreements GH000069–05 and U2GGH001520. The funding body did not play any role in the study design and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due them being service statistics sourced from public health facilities that are the property of Ministry of Health/ Government of Kenya but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

PEPFAR/CDC disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of this manuscript (DA, AW, THC, KM, EN, MK, IM, JO, RM, TA, AK, LN and KDC). IM, EN, MK, AK, and LN developed the idea for the study and assisted with study implementation. DA, KM, MK and EN were involved in data collection activities. DA, AW, EN, KM and MK participated in drafting and revising the manuscript with input from co-authors; AW, THC, LN, JO, TA, RM and KDC provided substantial revisions and intellectual content to the manuscript. AW analyzed the data and DA, IM, MK, EN and KM had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data. All authors (DA, AW, THC, KM, EN, MK, IM, JO, RM, TA, AK, LN and KDC) contributed to interpreting the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s Scientific and Ethics Review Unit, the Kenyatta National Hospital - University of Nairobi Ethics Review Committee as part of a nested study, and the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco. This study was reviewed according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) human research protection procedures and was determined to be and approved as research, but CDC was not engaged. As this research was retrospective, consent from study participants was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Achwoka, D., Waruru, A., Chen, TH. et al. Noncommunicable disease burden among HIV patients in care: a national retrospective longitudinal analysis of HIV-treatment outcomes in Kenya, 2003-2013. BMC Public Health 19, 372 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6716-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6716-2