Abstract

Background

There are many studies examining the relationship between body image and weight status that compare Western and Asian countries. One limitation of these past studies was assuming that all Asian countries are a homogeneous group. To fill the gap in the literature, this study examined the relationship between body image and weight status between participants from two Asian countries.

Methods

This study utilized data from the 2010 module of the East Asian Social Survey from South Korea (n = 1576) and Taiwan (n = 2199), which contained questions related to body image. Body image was originally measured using a five-point Likert-type question, which was collapsed into three categories for the analysis. Weight status was derived from body mass index scores, which were calculated using self-reported weight and height. A set of multinomial logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the relationship between body image and weight status, stratified by country.

Results

A significant relationship between body image and weight status after controlling for relevant covariates was reaffirmed in this study in the South Korean and Taiwanese. Results indicated that the relationship between body image and weight status of the Taiwanese sample was similar to the relationship in the South Korean sample. However, the results from a further analysis showed that the strength of the relationship across the two Asian countries appeared to be different.

Conclusions

The weight over-perception was more evident in South Korea than in Taiwan. Females were more vulnerable to societal pressures for thinness and the misperception of the ideal body than males. Interventions to improve distorted body image perception were needed in both countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Body image is a subjective image about one’s own body that plays a critical role in the perception of the physical self and the formation and representation of self-concept [1,2,3]. The body image can be divided into the ‘perceptual body image’, meaning an accurate perception or distorted awareness of one’s own body, and ‘attitudinal body image’, the attitude and feeling of one’s own body [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The perceptual body image today is known to be highly influenced by the media [2, 8,9,10,11]. Various body types and shapes portrayed by the media in television programs, movies, and magazines may shape viewers’ perceptions of ‘standard’ weight, overweight, and obese individuals [10, 12,13,14]. Specifically, overweight or obese people are often socially disparaged by the media because television in particular idealizes thin and slim characters [12].

On the other hand, attitudinal body image is closer to a feeling and attitude of the body. For instance, people that have been motivated by the thin and slim characters in the media and have exercised to keep their body fit tend to be more satisfied with their own bodies. However, most people are not satisfied with their body image after comparing their own bodies with slim characters portrayed in the media [5, 15,16,17,18].

Studies suggest that body image is associated with various psychological and emotional difficulties such as eating disorders, low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety [1, 7, 19,20,21,22]. Other studies of the psychological and emotional problems report that the perception that one has for one’s own body is similar to the perception that one has for oneself [20, 23].

It has been reported in the literature that the relationship between body image and actual weight status differs across various cultures and countries. In European countries, for example, overweight men and women tend to perceive themselves as normal weight, and obese men and women underestimate their weight status and categorize themselves as overweight [24]. Another study on people in the United States has shown that overweight Caucasian women tended to underestimate their weight, whereas overweight African American and Hispanic women did not report body image discrepancy [6]. In Asian studies, on the other hand, normal weight and underweight Taiwanese women had the tendency to view themselves as overweight, whereas Taiwanese men believe they are underweight [25, 26]. Korean women tend to overestimate their weight [27]. In Japan, similar to in Korea, underweight women view themselves as normal or overweight [28], and a high percentage of normal weight women believed themselves to be overweight [29]. In summary, many studies reported body image discrepancy, the pattern of which varies by different cultures and countries [30].

There are many studies examining the relationship between body image and weight status, but most of the studies have focused on samples from Western countries [6]. There are a few studies that compare Western and Asian countries in terms of the relationship between body image and weight status [31,32,33]. One limitation of these comparative studies was to assume that all Asian countries are a homogeneous group. There is a dearth of studies that compare multiple Asian countries in terms of BD. Using multi-national data from Asian countries, the present study aims to fill the aforementioned gap in the literature to compare the relationship between weight status and body image in samples from South Korea and Taiwan.

Methods

Data and subjects

This analysis utilized data from the East Asian Social Survey (EASS). The EASS was conducted through collaborative efforts in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The EASS data was made available through Sungkyunkwan University of Seoul, Korea, which is in charge of the management and distribution of the data. The EASS was conducted biannually from 2006 and asked a module of questions with a different topic for each year of the survey. This study utilized the 2010 module of the EASS, which included health-related questions. Specifically, the data from South Korea and Taiwan were analyzed because only these two countries asked questions related to body image.

The sample population of the EASS in Taiwan and South Korea included men and women 18 years or older. A multi-stage stratified random sampling procedure was implemented for each country and the response rates were 49.7% in Taiwan and 63.0% in South Korea. Failed contact attempts were the biggest reason for no response (Korea: 16.8%; Taiwan: 24.5%), followed by refusal (Korea: 12.3%; Taiwan 18.9%) and other reasons (Korea: 7.9%; Taiwan: 3.3%). In the 2010 module of EASS data, there were 1576 participants from South Korea and 2199 from Taiwan. Finally, this study excluded 124 respondents who did not provide BMI-related data.

EASS data are accessible via a public database (http://www.eassda.org). Our study was performed in accordance with ethical standards and was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Women’s University (SWU IRB-2017-6).

Variables and measurement

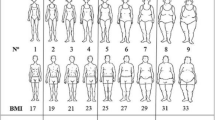

Body image was measured using a question asking “What do you think about your body shape?” Respondents were asked to answer this question using a five-point Likert scale comprised of 1 = ‘a lot underweight’, 2 = ‘a little underweight’, 3 = ‘neither underweight nor overweight’, 4 = ‘a little overweight’, and 5 = ‘a lot overweight’. This study collapsed the first two responses into one category of ‘consider underweight’ and the last two responses into another category of ‘consider overweight’ in the analysis. BMI was defined as the body mass divided by the square of the height and was calculated in this study using the respondents’ self-reported weight and height. BMI scores were used to classify the participants as underweight (under 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (between 18.5 kg/m2 and 23.0 kg/m2), overweight (between 23.0 kg/m2 and 25.0 kg/m2), obese (between 25.0 kg/m2 and 30.0 kg/m2), or severely obese (over 30.0 kg/m2) based on the World Health Organization’s classifications revised for the Asia-Pacific region. This study simplified the categories into three categories in the analysis: underweight/normal, overweight, and obese/severely obese. Other covariates in this analysis included age in years, gender (0 = male; 1 = female), marital status (1 = married or cohabiting; 0 = otherwise), region (1 = urban; 0 = otherwise), education in years, smoking behavior (1 = never smokes; 0 = otherwise) and alcohol consumption (1 = never drinks; 0 = otherwise).

Statistical analysis

A set of descriptive analyses stratified by country were conducted to summarize the characteristics of the samples and compare the countries. Given the categorical nature of body image—the dependent variable—a set of multinomial logistic regressions was used to investigate the relationship between body image and BMI stratified by country. To test whether the relationship between body image and BMI was different across country, another regression model with cross product interaction terms between BMI and country was calculated. Stata MP 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for data management and analyses, and the threshold for the significance test was p < 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Characteristics of participants from Korea and Taiwan were summarized in Table 1. The proportion of people who were normal weight or underweight was higher in Korea (57.0%) than in Taiwan (47.2%) whereas the proportion of obese or severely obese participants was lower in Korea (22.8%) than in Taiwan (33.2%). People in Taiwan were more likely to view themselves as overweight (49.1%) and less likely to view themselves as normal weight (37.3%) than people in Korea (35.9 and 46.7%, respectively). These differences in weight status (Chi-squared (1) = 50.3, p < 0.001) and body image (Chi-squared (1) = 64.5, p < 0.001) in the two countries were significant. Gender distribution (Chi-squared (1) = 1.7, p = 0.187) and age (t = 1.6, p = 0.102) of the study participants between Korea and Taiwan were not significantly different. However, there were significant differences found in marital status (Chi-squared (1) = 7.6, p < 0.01), region (Chi-squared (1) = 9.4, p < 0.01), smoking status (Chi-squared (1) = 345.3, p < 0.001), alcohol drinking status (Chi-squared (1) = 5.2, p < 0.05), and years of education (t = 3.1, p < 0.01) (Table 1).

The distribution of weight status by gender for Korea and Taiwan, respectively, were summarized in Table 2. In Korea, there are 57.3% of female and 41.6% of male of normal weight, 11.3% of female and 2.7% of male of underweight, 14.3% of female and 26.7% of male of overweight, 15.4% of female and 26.2% of male of obese, and 1.8% of female and 2.8% of male of severely obese. In Taiwan, 8.1% of female and 3.5% of male were underweight, 48.4% of female and 34.6% of male normal weight, 16.8% of female and 22.2% of male overweight, 21.3% of female and 34.1% of male obese, and 5.4% of male and female, respectively, severely obese. Overall, these differences between male and female were significant in Korea (Chi-squared (4) = 112.3, p < 0.001) and in Taiwan (Chi-squared (4) = 82.9, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

As presented in Table 3, respondents’ self image of body shape tended to be coherent with their weight status both in Korea and in Taiwan. However, there were 35 Koreans (4.8%) and 38 Taiwanese (4.9%) who answered their body shape image being not underweight while they were underweight by their BMI. Also, there were 163 Koreans (47.1%) and 227 Taiwanese (32.8%) who consider themselves as overweight even though they were categorized as normal weight by their BMI (Table 3).

Table 4 presents the results from multinomial logistic regression analysis of body image on weight status after controlling for other relevant covariates for Korea and Taiwan, respectively. The results showed that, in Korea, those who were overweight (B (SE) = − 2.66 (0.34), p < 0.001) or obese or severely obese (B (SE) = − 2.87 (0.52), p < 0.001) compared to underweight or normal weight, were less likely to consider themselves as underweight than as normal weight. Those who were overweight (B (SE) = 1.55 (0.19), p < 0.001) or obese or severely obese (B (SE) = 3.27 (0.21), p < 0.001) compared to underweight or normal weight were more likely to consider themselves as overweight than normal weight after controlling for relevant covariates such as age, gender, marital status, region, education, and health related behaviors such as smoking and alcohol drinking. Table 4 shows the same results for the Taiwan sample. After controlling for relevant covariates such as age, gender, marital status, region, education, and health related behaviors such as smoking and alcohol drinking, people in Taiwan who were overweight (B (SE) = − 1.70 (0.26), p < 0.001) or obese or severely obese (B (SE) = − 2.38 (0.41), p < 0.001) compared to underweight or normal weight, were less likely to consider themselves as underweight than as normal weight. Those who were overweight (B (SE) = 2.07 (0.17), p < 0.001) or obese or severely obese (B (SE) = 3.67 (0.18), p < 0.001), compared to underweight or normal weight, were more likely to consider themselves as overweight than normal weight in Taiwan (Table 4).

Results indicated that the Taiwanese sample showed a similar pattern as the Korean sample in the relationship between body image and weight status. Nevertheless, the strength of the relationship seemed to differ between the two Asian countries. We further tested whether the relationship between weight status and body image was different in Korea and Taiwan; results are summarized in Table 5. A multinomial logistic regression analysis results showed that the regression coefficient of the overweight group compared to the underweight or normal group in the likelihood of considering themselves as underweight than as normal weight was smaller in Taiwan compared to Korea (B (SE) = 0.84 (0.42), p = 0.046). In other words, while people both in Korea and Taiwan who were overweight were less likely to consider themselves as underweight than as normal weight, the relationship was stronger in the Korean sample compared to the Taiwanese sample (Table 5).

Discussion

Recent research has focused public attention on obesity and distorted body image, and found that cultural norms, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status influence the relationship between BMI and body image [34, 35]. According to the International Health and Behavior Survey, which collected data from 22 countries, perceptions of overweight in young men and women across BMI deciles were similar across diverse regions of the world, but Asians showed higher levels of trying to lose weight. Additionally, being female was related to feeling overweight at any BMI decile [35].

In this study, both Korean and Taiwanese individuals perceived they were overweight or obese even though they were not, which is consistent with previous studies [36,37,38,39,40]. As two neighboring East Asian countries, South Korea and Taiwan showed similar cultural and historical backgrounds, such as a Confucian culture, independence after World War II, rapid economic development, industrialization, and democratic politics [41]. In this study, Koreans were more overestimate their weight than Taiwanese to their body image. Body dissatisfaction, distorted perception of weight and body image, and disordered eating behaviors were more widespread in South Korea than in the West and China [42]. This weight over-perception and dissatisfaction of body image may explain the high rate of plastic surgery including liposuction in South Korea. According to statistics released by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery [43], the estimated number of plastic surgeons was 2150 in South Korea, while 600 in Taiwan even though the population of South Korea is twice that of Taiwan [44, 45].

The rate of overestimation of their weight status among women was higher than that of men in both countries, but the discrepancy in BMI and body image in South Korea was stronger than in Taiwan in this study. Studies of Korean populations have consistently shown that Korean females perceived they are overweight or obese even though their weight was in the normal weight range [37, 38, 46, 47]. Korean females had a higher prevalence of weight over-perception than Korean males, which led to more weight control behavior [35, 37, 42], which may explained that disordered eating behaviors were more widespread in South Korea than in the West, China, and Japan [42]. This discrepancy in BMI and body image could be caused by their substantial exposure to mass media, which conveys the idea that losing weight is a high priority in females [48, 49]. This study could not use exposure to media or the effect of types of media on body image as a covariate, but many studies reported that exposure to the ‘thin ideal’ (the ideally slim female body) via television, magazine, film, social media, and advertisements made females perceived they were overweight [11, 18, 41]). Korean females showed high interest in their appearance and weight regardless of their actual body physique, and they in past research had concerns with weight and thin body shape, which led to reductions in both self-esteem and satisfaction with their appearance [47]. There are specific Korean terms to describe appearance thin body shape, such as ‘momjjang’ (a well-toned body) [50].

The desire to thin body shape may be related to inappropriate eating behavior and unhealthy weight loss behaviors in South Korea [51, 52]. A study compared the dietary pattern and body shape preference of female undergraduate students in South Korea and Japan [52]. Korean females showed a more irregular eating pattern and ate less frequently. Korean females’ ideal BMI was 18.4, which belonged to the underweight category [52]. In some severe cases, the misperception that they are obese even though they were not in Korean female could lead to eating disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia [53], depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal plans [54].

There was no study to compare the perception of body image in South Korea to that of in Taiwan. Previous findings showed that body dissatisfaction was less common among males in Taiwan than those of the U.S. and Europe [55]. Taiwanese females had a weight over-perception compared to males much like females in South Korea. The ideal figure of females was thinner than the figure that males rated as most attractive to them, while the ideal figure of males was heavier than females actually preferred [40] Similar to in South Korea, media exposure acted as a conduit for thin-ideal messages, and led to increased body dissatisfaction, which ultimately contributed to restrained eating and unhealthy weight control behaviors [41].

This study has several limitations. The main limitation is that a cross-sectional study design cannot determine cause-effect relationships between BMI and self-rated body image. Another limitation is that this study cannot include all confounding covariates, which may have biased the study findings. Lastly, data from only two East Asian countries limits the generalizability of the study findings. In spite of several limitations, the study has some strengths. This study was the first study to compare the relationship between BMI and body image in South Korea to that in Taiwan, two neighboring countries with similar cultural and historical backgrounds. The findings provide insights in similarities and differences in weight over-perception in South Korea and Taiwan.

Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between body image and weight status between participants from two East Asian countries. The relationship between body image and weight status of the Taiwanese samples was similar to the relationship in the South Korean samples. However, the results from a further analysis showed that the strength of the relationship across the two Asian countries appeared to be different. The weight over-perception was more evident in South Korea than in Taiwan. Females were more vulnerable to societal pressures for thinness and the misperception of the ideal body than males. Overall, interventions to amend distorted body image perception are needed in both countries.

Abbreviations

- BD:

-

Body Image Discrepancy

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- EASS:

-

East Asian Social Survey

References

Rierdan J, Koff E. Weight, weight-related aspects of body image, and depression in early adolescent girls. Adolescence. 1997;32(127):615.

Mills JS, Polivy J, Herman CP, Tiggemann M. Effects of exposure to thin media images: evidence of self-enhancement among restrained eaters. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(12):1687–99.

D'Alessandro S, Chitty B. Real or relevant beauty? Body shape and endorser effects on brand attitude and body image. Psychol Mark. 2011;28(8):843–78.

Rucker CE, Cash TF. Body images, body-size perceptions, and eating behaviors among African-American and white college women. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;12(3):291–9.

Chen W, Swalm RL. Chinese and American college students’ body-image: perceived body shape and body affect. Percept Mot Skills. 1998;87(2):395–403.

Fitzgibbon ML, Blackman LR, Avellone ME. The relationship between body image discrepancy and body mass index across ethnic groups. Obes Res. 2000;8(8):582–9.

Tovée MJ, Benson PJ, Emery JL, Mason SM, Cohen-Tovée EM. Measurement of body size and shape perception in eating-disordered and control observers using body-shape software. Br J Psychol. 2003;94(4):501–16.

Botta RA. Television images and adolescent girls’ body image disturbance. J Commun. 1999;49(2):22–41.

Botta RA. The mirror of television: a comparison of black and white adolescents’ body image. J Commun. 2000;50(3):144–59.

Rudd NA, Lennon SJ. Body image: linking aesthetics and social psychology of appearance. Cloth Text Res J. 2001;19(3):120–33.

Jarry JL, Kossert AL. Self-esteem threat combined with exposure to thin media images leads to body image compensatory self-enhancement. Body Image. 2007;4(1):39–50.

Greenberg BS, Eastin M, Hofschire L, Lachlan K, Brownell KD. Portrayals of overweight and obese individuals on commercial television. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1342–8.

Fouts G, Burggraf K. Television situation comedies: female body images and verbal reinforcements. Sex Roles. 1999;40:473–81.

Tiggemann M. Television and adolescent body image: the role of program content and viewing motivation. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005;24(3):361–81.

Williamson DA, Gleaves DH, Watkins PC, Schlundt DG. Validation of self-ideal body size discrepancy as a measure of body dissatisfaction. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1993;15(1):57–68.

Hargreaves D, Tiggemann M. Longer-term implications of responsiveness to ‘thin-ideal’television: support for a cumulative hypothesis of body image disturbance? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2003;11(6):465–77.

Yates A, Edman J, Aruguete M. Ethnic differences in BMI and body/self-dissatisfaction among whites, Asian subgroups, Pacific islanders, and African-Americans. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(4):300–7.

Brown A, Dittmar H. Think “thin” and feel bad: the role of appearance schema activation, attention level, and thin-ideal internalization for young women's responses to ultra-thin media ideals. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005;24(8):1088–113.

Lennon SJ, Rudd NA, Sloan B, Kim JS. Attitudes toward gender roles, self-esteem, and body image: application of a model. Cloth Text Res J. 1999;17(4):191–202.

Keppel CC, Crowe SF. Changes to body image and self-esteem following stroke in young adults. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2000;10(1):15–31.

Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Costanzo PR, Musante GJ. Body image partially mediates the relationship between obesity and psychological distress. Obes Res. 2002;10(1):33–41.

Johnson F, Wardle J. Dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, and psychological distress: a prospective analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(1):119–25.

Secord PF, Jourard SM. The appraisal of body-cathexis: body-cathexis and the self. J Consult Psychol. 1953;17(5):343–7.

Sanchez-Villegas A, Madrigal H, Martínez-González MA, Kearney J, Gibney MJ, De Irala J, et al. Perception of body image as indicator of weight status in the European Union. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14(2):93–102.

Li YM, Fu CC. Weight, weight perception and psychiatric distress in freshmen at a national university in Hualien County. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2005;17:169–75.

Page RM, Lee CM, Miao NF. Self-perception of body weight among high school students in Taipei, Taiwan. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2005;17:123–36.

Kim SW. Body weight and body image: a risk factor analysis in Korea. Asian J Public Opin Res. 2011;12(3):143–72.

Ohara K, Kato Y, Mase T, Kouda K, Miyawaki C, Fujita Y, et al. Eating behavior and perception of body shape in Japanese university students. Eat Weight Disord. 2014;19(4):461–8.

Inoue M, Toyokawa S, Inoue K, Suyama Y, Miyano Y, Suzuki T, et al. Lifestyle, weight perception and change in body mass index of Japanese workers: MY health up study. Public Health. 2010;124:530–7.

Noh JW, Kim J, Yang Y, Park J, Cheon J, Kwon YD. Body mass index and self-rated health in east Asian countries: comparison among South Korea, China, Japan, and Taiwan. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183881.

Wardle J, Bindra R, Fairclough B, Westcombe A. Culture and body image: body perception and weight concern in young Asian and Caucasian British women. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 1993;3(3):173–81.

Altabe M. Ethnicity and body image: quantitative and qualitative analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(2):153–9.

Bush HM, Williams RG, Lean ME, Anderson AS. Body image and weight consciousness among south Asian, Italian and general population women in Britain. Appetite. 2001;37(3):207–15.

Dinsa GD, Goryakin Y, Fumagalli E, Suhrcke M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in developing countries: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13(11):1067–79.

Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A. Body image and weight control in young adults: international comparisons in university students from 22 countries. Int J Obes. 2006;30(4):644–51.

Joh HK, Oh J, Lee HJ, Kawachi I. Gender and socioeconomic status in relation to weight perception and weight control behavior in Korean adults. Obes Facts. 2013;6(1):17–27.

Lim YS, Park NR, Jeon SB, Jeong SY, Tserendejid Z, Park HR. Analysis of weight control behaviors by body image perception among Korean women in different age groups: using the 2010 Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey data. Korean J Community Nutr. 2015;20(2):141–50.

Chen LJ, Fox KR, Haase AM, Ku PW. Correlates of body dissatisfaction among Taiwanese adolescents. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(2):172–9.

Shih MY, Kubo C. Body shape preference and body satisfaction in Taiwanese college students. Psychiatry Res. 2002;111:215–28.

Chang FC, Lee CM, Chen PH, Chiu CH, Pan YC, Huang TF. Association of thin-ideal media exposure, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors among adolescents in Taiwan. Eating Behav. 2013;14(3):382–5.

Scitovsky T. Economic development in Taiwan and South korea, 1965–1981. San Francisco: ICS Press; 1985.

Jung J, Forbes GB. Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among college women in China, South Korea, and the United States: contrasting predictions from sociocultural and feminist theories. Psychol Women Q. 2007;31(4):381–93.

International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2015: International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery; 2016. Available from: https://www.isaps.org/medical-professionals/isaps-global-statistics/

Korean Statistical Information Service. 2017. Statistical Database. Available from: http://kosis.kr/

National Statistics Republic of China, 2016. Latest Indicators. Available from http://eng.stat.gov.tw/point.asp?index=9

Kang YH, Kim KH. Body weight control behavior and obesity stress of college women. Jour of KoCona. 2015;15:292–300.

Jeong SJ, Sato M, Chu MS. The effects of perception of body shape, self-esteem, body cathexis, and body image on fashion leadership by Korean and Japanese female college students. Fashion & Text Res. 2013;15:713–21.

Choi Y, Choi E, Shin D, Park SM, Lee K. The association between body weight misperception and psychosocial factors in Korean adult women less than 65 years old with normal weight. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(11):1558–66.

Inoue M, Toyokawa S, Miyoshi Y, Miyano Y, Suzuki T, Suyama Y, et al. Degree of agreement between weight perception and body mass index of Japanese workers: MY health up study. J Occup Health. 2007;49(5):376–81.

Un PS. “Beauty will save you”: the myth and ritual of dieting in Korean society. Korea J. 2007;47(2):41–70.

Ro Y, Hyun W. Comparative study on body shape satisfaction and body weight control between Korean and Chinese female high school students. Nutr Res Pract. 2012;6(4):334–9.

Sakamaki R, Amamoto R, Mochida Y, Shinfuku N, Toyama KA. Comparative study of food habits and body shape perception of university students in Japan and Korea. Nutr J. 2005;4:31.

Woo J. A survey of overweight, body shape perception and eating attitude of Korean female university students. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem. 2014;18(3):287–92.

Kim BS, Chang SM, Seong SJ, Park JE, Park S, Hong JP, et al. Association of Overweight with the prevalence of lifetime psychiatric disorders and suicidality: general population-based study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1814–21.

Yang CF, Gray P, Pope HG Jr. Male body image in Taiwan versus the west: Yanggang Zhiqi meets the Adonis complex. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):263–9.

Funding

This work was supported by the special research grant from Seoul Women’s University (2018).

Availability of data and materials

Data used in this study are available via a public website, http://www.eassda.org. “EASS is a biennial social survey projects that purports to produce and disseminate academic survey data sets in East Asia. As a crossnational network of GSS-type surveys, EASS is dedicated to the promotion of comparative studies on diverse aspects of social lives in East Asia. Launched in 2003, EASS is one of the few international social survey data collections efforts, and is truly unique for its East Asian focus.” quote from (http://www.eassda.org).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JN, YK, and JK conceived of the study, and discussed data analysis results. JK performed the data management and the statistical analysis. YY and JC participated in reviewing the relevant literature and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was performed in accordance with ethical standards and was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Women’s University (SWU IRB-2017-6). Because this study is a secondary data analysis, the need for written consent was formally waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Noh, JW., Kwon, Y.D., Yang, Y. et al. Relationship between body image and weight status in east Asian countries: comparison between South Korea and Taiwan. BMC Public Health 18, 814 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5738-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5738-5