Abstract

Background

Reducing automobile dependence and improving rates of active transport may reduce the impact of obesogenic environments, thereby decreasing population prevalence of obesity and other diseases where physical inactivity is a risk factor. Increasing the relative cost of driving by an increase in fuel taxation may therefore be a promising public health intervention for obesity prevention.

Methods

A scoping review of the evidence for obesity or physical activity effect of changes in fuel price or taxation was undertaken. Potential health benefits of an increase in fuel excise taxation in Australia were quantified using Markov modelling to simulate obesity, injury and physical activity related health impacts of a fuel excise taxation intervention for the 2010 Australian population. Health adjusted life years (HALYs) gained and healthcare cost savings from diseases averted were estimated. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were reported and results were tested through sensitivity analysis.

Results

Limited evidence on the effect of policies such as fuel taxation on health-related behaviours currently exists. Only three studies were identified reporting associations between fuel price or taxation and obesity, whilst nine studies reported associations specifically with physical activity, walking or cycling. Estimates of the cross price elasticity of demand for public transport with respect to fuel price vary, with limited consensus within the literature on a probable range for the Australian context. Cost-effectiveness modelling of a AUD0.10 per litre increase in fuel excise taxation using a conservative estimate of cross price elasticity for public transport suggests that the intervention would be cost-effective from a limited societal perspective (237 HALYs gained, AUD2.6 M in healthcare cost savings), measured against a comparator of no additional increase in fuel excise. Under “best case” assumptions, the intervention would be more cost-effective (3181 HALYs gained, AUD34.2 M in healthcare cost savings).

Conclusions

Exploratory analysis suggests that an intervention to increase fuel excise taxation may deliver obesity and physical activity related benefits. Whilst such an intervention has significant potential for cost-effectiveness, potential equity and acceptability impacts would need to be minimised. A better understanding of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a range of transport interventions is required in order to achieve more physically active transport environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical inactivity is a global public health problem. Modern society has replaced many daily actions involving physical activity (PA) with motorised and computerised alternatives, and populations are now experiencing unprecedented levels of conditions such as obesity and other non-communicable diseases where physical inactivity is a risk factor. The increasing global burden of largely preventable diseases has led to recognition of the need for ‘upstream’ interventions for prevention [1, 2]. These interventions focus on macro-level factors and include government policies and social, physical, economic and environmental levers for change across increasingly obesogenic environments [3–6].

The transportation sector is increasingly being recognised for its potential contribution to improving population levels of incidental PA. Active transport (AT, defined as walking, cycling and use of public transport) reduces the risk of all-cause mortality [7] and cardiovascular disease [8] and may deliver other significant health and environmental co-benefits [9]. Rates of car ownership have dramatically increased worldwide in recent decades. Many countries, such as Australia, are highly car dependent with low prevalence of AT (for example, in Australia only 2% of the employed population in 2012 cycled to work, and 4% walked) [10]. Recent studies have suggested associations between transport mode and obesity, with more active forms of transport being negatively associated with measures of adiposity [11–14]. Whilst evidence on the obesity effect of modal choice is currently relatively limited [15, 16], interventions that encourage more active forms of transport may offer potential as population health strategies for obesity prevention.

The complexities of changing transport behaviours and re-engineering car-centric environments are however large. Transport behaviours are influenced by a wide range of factors, including the characteristics of travel modes (for example cost, availability, ease, comfort), individual influences (for example age, gender, income, physical ability) and contextual factors (for example culture, the built environment, climate, topography) [17]. Whilst it is recognised that a combination of legal, economic, communication and physical approaches to intervention will most likely be required to encourage modal shift [18], the reality is that very little is currently known about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of specific transport interventions when incorporating health, environmental and other effects [19, 20].

This paper seeks to conduct a scoping review and cost-effectiveness modelling study of a specific transport intervention that may encourage modal shift to more active forms of transport - an increase in automotive fuel excise taxation. To date, limited studies have been conducted into the potential effect of changes in fuel taxation on health related behaviours. A review by Mozaffarian et al. [21] used a Delphi approach and found that the evidence of effect for increasing participation in AT by raising fuel prices was not well-established but that the intervention might be considered. The review by Martin et al. [22] suggested that financial incentives, including the negative financial incentive of increased fuel price, may play a role in increasing PA however more rigorous evidence is required to make better use of effectiveness evidence in resource allocation decision-making. In 2013, Dhondt et al. [23] undertook the only study quantifying the health impact of an increase in fuel price published to date, but included only mortality related health benefits of an increase in walking and cycling and not morbidity-related health impacts. Our study therefore contributes to this literature by synthesising the current body of evidence for an obesity-related health effect of fuel excise taxation and conducting a scenario analysis detailing potential health gains and cost-effectiveness of a change in policy.

Methods

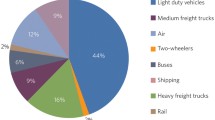

Taxation on fuel is common worldwide. Excise duty is a tax levied on alcohol, tobacco and fuel and petroleum products produced, stored or manufactured in Australia. The excise provides a general source of revenue to the Australian government [24]. Australia currently has the fourth lowest automotive fuel price of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries [25]. The proportional amount of tax levied on Australian fuel is also low in comparison to almost all other OECD countries (Fig. 1), and has been decreasing in recent years [26].

Fuel price for selected OECD countries, March quarter 2016. AUD=Australian dollars. 1 AUD equals approximately 0.74 US dollars or 0.59 British pounds as of November 2016. Source: Australian Government Office of the Chief Economist [35]

By increasing the relative cost of driving to the motorist, government intervention to increase fuel excise taxation may present a feasible logic pathway to encouraging more AT across populations (Fig. 2). The price signal may lead to increased walking, cycling and use of public transport (PT). This in turn may lead to an increase in energy expenditure (assuming that PA-related behavioural substitution does not occur), a change in body mass index (BMI) (assuming there is no corresponding change in energy intake) and improved obesity and PA-related health outcomes.

A scoping review was therefore undertaken to explore the evidence and to inform parameters for cost-effectiveness modeling of an intervention to increase fuel excise taxation. The premise for the increase in tax in this paper is based on its potential to improve rates of AT. The scoping review consisted of two parts, described below.

Scoping review of published associations between obesity, PA, walking or cycling and fuel price or taxation

A scoping review of the evidence for PA or obesity effect of motor vehicle fuel price or taxation was undertaken in May 2016. Given the scoping nature of the search, one reviewer (VB) designed and undertook the search strategy, whilst the second reviewer (RC) verified the strategy and resultant inclusions. The EBSCOHost and Web of Science databases were searched for papers reporting associations between fuel price or taxation and obesity, PA, walking or cycling effects. The full search strategy is given in Appendix 1. Study aims, methods and results were extracted and study quality was assessed by one reviewer (VB), using criteria based on the Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [27] and criteria adapted from previous studies [14, 28] (Appendix 2).

Scoping review of published cross price elasticities of public transport demand for the Australian context

Given that PT accessibility predominantly relies on walking trips [29, 30], studies reporting on the cross price elasticity of PT may also be relevant when examining obesity-related effects of transport policy. Cross price elasticity is defined as the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of one good to a change in the price of another good [31]. Cross price elasticities of demand for PT with respect to fuel price may be context dependent [32]. Therefore a scoping review of published estimates of cross price elasticity of demand for PT with respect to fuel price suitable for the Australian context was conducted.

The Australian Government Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE) maintains a transport elasticities database that is freely and publicly available [33]. A search was conducted of all tables listed in the database reporting values of cross price elasticity for PT with respect to fuel price. A non-systematic search was then conducted for reviews or meta-analyses reporting estimates. The EBSCOHost and Web of Science databases were searched using key terms, including “public transport*”, “transit”, “meta-analysis”, “review”, “systematic review” and “elasticit*”. A search of the grey literature was also undertaken to capture any potential inclusions from other government or non-peer reviewed sources. The full search strategy is given in Appendix 1.

Data selection and cost-effectiveness modelling

Evidence from the scoping review was used to conduct scenario analyses of the cost-effectiveness of a fuel excise taxation increase for the Australian population, incorporating both mortality and morbidity effects. The intervention was defined as an AUD0.10 per litre increase to the national fuel excise tax [34], which as of June 2010 was AUD0.38143 cents per litre [34]. An increase in excise of AUD0.10 would mean that the proportional amount of tax levied as a percentage of total fuel price would be higher, but still less than in countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom [35]. The increase in excise was assumed to apply prior to the addition of the 10% Goods and Services Tax (GST), and it was assumed that the economic incidence of the increased tax was borne by the consumer (a realistic assumption given the relatively price inelastic nature of automotive fuel in Australia [36, 37]).

A proportional multi-state, multiple cohort life table model estimated obesity and PA-related health outcomes for the 2010 Australian population. Key model variables are listed in Table 1. Health outcomes were modelled as the difference between: (i) the 2010 reference year Australian population BMI and PA distributions; and (ii) the intervention population, which was identical to the reference population but incorporated changes to BMI and PA attributable to the intervention. Data on transport behaviours are not comprehensively collected in Australia at the national level, however the five-yearly Australian Bureau of Statistics Census of Population and Housing collects reliable data on the method of transport to work [38]. Therefore the intervention population was defined as the working age population (aged 18 to 64 years) and the impact of commuting modal switch as a hypothetical result of the intervention was estimated.

The multi-state life table method incorporated disease-specific lifetables to estimate mortality and morbidity for nine obesity-related diseases and five overlapped PA-related diseases (ischaemic heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, ischemic stroke, diabetes, colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, breast cancer, endometrial cancer and osteoarthritis). Modal shift to more active forms of transport may also change the risk of injury from transport accidents. The ‘risk injury matrix approach’, as proposed by Bhalla et al. [39] and used in several health impact assessments [40–42], was adapted to estimate the change in absolute numbers of mode-specific fatalities and serious injuries as a result of the intervention. Estimates were then incorporated into the lifetable modelling, and compared with baseline mode-specific road traffic accident deaths and years lived with disability (YLD) from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2010 [43]. PA effect from the intervention was modelled using effect estimates from the scoping review and relevant input parameters. To ensure conservative results, any uptake in PA as a result of the intervention was assumed to have occurred in those already moderately or highly physically active in their daily lives. PA effect was modelled to BMI effect using the energy balance equation by Hall et al. [44] (Appendix 3). In the absence of evidence on the long-term effects of fuel price increases on public transport use, we assumed that the behavior change would be sustained (i.e. that those who switched to public transport continued to use public transport over the long-term).

Data on healthcare costs were obtained from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) for 2001 due to data availability [45], and inflated to 2010 prices using the Health Price Index [46]. Intervention costs were regarded as minimal given that: (i) fuel excise taxation, with bi-annual indexation, already occurs within Australia; and (ii) the excise is levied at the point of production or import and there are relatively few producers/importers of transport fuels in Australia. It is therefore expected that the administrative and compliance burden of the tax would be relatively low [47]. Intervention costs were estimated using information from an Australian Government Regulatory Impact Statement [48] and publicly available data on wage costs and use of parliamentarians time [48–51] Costs and cost savings were discounted at 3% and all values are reported in AUD2010 dollars (Table 1).

Economic evaluations of transport interventions differ in their inclusions of other potential cost or cost saving categories [20]. Travel time savings and car parking cost savings are difficult to generalise given the large scope for variation in costs when modelling nationally, and therefore have not been included in our analysis. Decongestion and environmental benefits are also difficult to generalise on a national basis and therefore have also been omitted. Vehicle operating cost (VOC) savings related to fuel and repairs and maintenance were estimated using conservative parameter values from Australian guidelines [52] and reported separately as potential replacement expenditure per new active traveller (i.e. as resource corrections between automobile and PT usage costs). We assume that those new to AT will continue to own and use private motor vehicles for other purposes. For consumers changing their travel behaviours in response to financial incentives, the ‘rule of half’ was applied to VOC savings as per national guidelines [52]. The ‘rule of half’ is based on the economic theory that when consumers change their travel in response to a financial incentive, the net consumer surplus is equivalent to half of their price change [53].

Health adjusted life years (HALYs) gained were estimated by comparing the intervention to the ‘do-nothing’ comparator. A limited societal perspective was adopted, with the time horizon for estimating cost offsets and HALY benefits being rest-of-life or 100 years. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated by dividing the difference in the net cost of the intervention by the difference in the net health benefit. ICER results are presented on a cost-effectiveness plane, where interventions that are both cost saving and of benefit to health are considered ‘dominant’. Interventions falling in the other quadrants of the plane will be determined as cost-effective using the AUD50,000 per HALY threshold as per Australian benchmarks [54].

All modeling was undertaken using Excel 2010, with uncertainty analysis around the relative risk of incident disease and key input parameters estimated by Monte Carlo simulation using the Excel add-in Ersatz (version 1.34) [55]. For input parameters with considerable uncertainty, we have adopted a conservative approach to estimation of potential cost-effectiveness. One-way sensitivity analyses were then undertaken to test the validity of assumptions and robustness of results [56]. We also present “plausible case” scenario results, using higher but still credible values as an indication of the potential range for cost-effectiveness. Parameters for sensitivity analyses are given in Appendix 4.

Consideration of the broader impacts of an intervention should also be considered alongside any cost-effectiveness analysis, in order to take into account factors that are important to decision-makers but difficult to quantify within the analysis [3, 56]. Cost-effectiveness results are therefore discussed alongside a “second stage filter analysis”, which analyses potential equity, feasibility, acceptability and sustainability effects of the intervention.

Results

Results from the scoping review of published associations between obesity, PA, walking or cycling and fuel price or taxation

A total of 12 studies were included in our evidence review of obesity, PA, walking or cycling associations with fuel taxation or price (Fig. 3). Limited evidence currently exists in the peer-reviewed literature on the effect of fuel price or taxation on obesity specifically, with only three primary studies found [57–59] (Table 2). All three studies were cross-sectional study designs, and only the study by Courtemanche [57] examined individual level effects.

Nine studies specifically explored the association between fuel taxation or price and PA, walking or cycling [60–68](Table 2). The majority of these studies (89%) were cross-sectional [61–68]; with only one longitudinal study investigating the relationship between fuel price and leisure PA [60]. Over half of these studies (55%) reported specifically on associations between fuel taxation or price and cycling [63–65, 67, 68], perhaps reflective of the increasing evidence of the positive health benefits of cycling for utilitarian purposes [69].

The mean quality assessment score of all included studies was relatively low (6 out of a possible score of 10, range 4 to 8) (Appendix 5), and is partly attributable to the use of cross-sectional study designs and self-reported outcomes. The challenges of collecting rigorous evidence of effect for environmental or policy-type interventions are well-recognised, with calls for better use of ‘natural experimental’ designs and a more pragmatic approach to the traditional hierarchies of evidence for interventions not amenable to evaluation through controlled circumstances [70, 71].

Results from the scoping review of published cross price elasticities of PT demand

Estimates of cross price elasticity of demand for PT with respect to fuel price vary due to geographical location, time and modal share, but also due to model specification, statistical methods and quality of data used [72, 73]. Our scoping review found eight relevant studies reporting on cross price elasticity of PT demand with respect to fuel price. Two estimates of cross price elasticity were found from the search of the BITRE database [33], and six estimates were found from our non-systematic search [73–78] (Table 3).

Overall, limited consensus exists on values for either short-run or long-run cross price elasticity of demand for PT with respect to fuel price. The study by Currie & Phung [74] cited cross price elasticities within a probable range of 0.07 to 0.80, although authors noted the wide range and potential for variability from use of these estimates. In a subsequent paper, the authors estimated variability between different Australian cities at different times of day and between different PT modes, finding that variations in service levels, infrastructure and peak vs. non-peak travel may explain some differences [75].

The review by Kennedy & Wallis [76] found that cross price elasticities for rail services may be higher than those for other PT modes, citing a range of 0.48 to 0.80 for rail and recommending lower cross price elasticities for general PT services from around zero to 0.20. The review by Luk & Hepburn [77] recommended a short-run cross price elasticity of 0.07. The updated review by Litman [73] recommended cross price elasticity values of between 0.05 and 0.15 in the short-run and between 0.2 and 0.4 in the long-run, incorporating Australian studies into the analysis of this probable range.

Holmgren [78] conducted a meta-analysis of bus demand elasticities and estimated the expected values for cross price elasticity of demand with respect to petrol price for Australia as 0.82 in the short-run (95% UI 0.56–1.08) and 1.15 in the long-run (95% UI 0.65–1.65). The author suggested that estimates were much higher for Australia than Europe (short-run cross price elasticity in Europe 0.4 (95% UI 0.16–0.64), long-run cross price elasticity in Europe 0.73 (95% UI 0.38–1.08)). Estimates from the meta-analysis are also obviously much higher than other studies reported here (Table 3). The mean cross price elasticity of demand for PT with respect to fuel price across all 17 included studies by Holmgren 2007 [78] was 0.38 (s.e 0.31), although no detail was given on the search method or inclusion criteria for studies and references of the included studies were not cited.

Results from cost-effectiveness modelling

Due to the relatively limited evidence of obesity, PA, walking or cycling effect (Table 2), cost-effectiveness scenarios of an increase in fuel taxation were modelled using conservative estimates of cross price elasticity of demand for public transit with respect to fuel price and key input parameters. To avoid over-estimating potential health benefits, we selected the conservative cross price elasticity value of 0.07, with potential health benefits resulting from the increase in walking to access PT as the basis for our hypothetical main scenario. Key input parameters for estimation of intervention effect are given in Table 4.

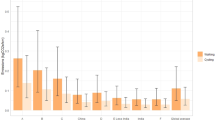

Based on our conservative modelling inputs and assuming effect stability over the lifetime, 237 HALYs would be gained as a result of the intervention (95% UI 138–351). A total of AUD2.6 M in healthcare costs would be averted (95% UI AUD1.3 M–3.9 M)(Table 5). The intervention would result in an overall decrease in mortality and morbidity from traffic accidents (3 deaths averted and 79 years lived with disability (YLDs) averted). The ICER suggests that the intervention would be cost-effective over the lifetime, with a median ICER of 7702 (95% UI 1366–22,125). The probability of the intervention being dominant (cost saving) however is only 0.8% (Table 5, Fig. 4).

If we model only health-related costs and benefits of diseases related to obesity (and omit the independent effects of diseases related to PA and mortality and morbidity from the change in risk of injury) 195 HALYs would be gained over the lifetime (95% UI 85–314), with AUD2.3 M in obesity-related healthcare cost savings (95% UI AUD0.96 M–3.8 M). If only considering the obesity-related effects the intervention is still considered cost effective with a median ICER of 10,514 (95% UI 1843–39,990), however the probability of the intervention being dominant is only 0.3% (Table 5, Fig. 4).

One-way sensitivity analyses were undertaken to test the robustness of results to variations in some of the key input parameters, especially those where uncertainty analysis was not possible due to data constraints (Table 5) (Appendix 4). Our cost-effectiveness results are very sensitive to the choice of cross price elasticity used (Table 5). Both sensitivity analyses varying cross-price elasticity result in far higher HALY and healthcare cost saving estimates and the intervention is dominant. The burden of morbidity and mortality from traffic accidents is also reduced in both scenarios (14 deaths and 356 YLDs averted (cross price elasticity 1); 20 deaths and 501 YLDs averted (cross price elasticity 2)).

Evidence also suggests that people will walk more than 400 m to access trains in particular, with 800 m regarded as the planning “rule-of-thumb” and some research demonstrating that 800 m may still be a conservative estimate for train accessibility [79, 80]. If we vary the distance walked to access PT to 800 m in our main analysis the intervention is also dominant (Table 5). Increased distance to access PT would however result in an increase in mortality from traffic accidents (5 fatalities gained) but a decrease in morbidity (33 YLDs averted) due to the change in traffic exposure. The use of 3.5 METs for walking is also relatively conservative when estimating walking for commuting purposes [81]. Obviously use of a higher MET value for walking to access PT would also result in greater health benefits and cost-effectiveness.

Due to the fact that many of the input parameters for our main analysis are relatively uncertain but based on conservative estimates, we modelled a “plausible case” cost-effectiveness estimate using the input parameters given in Appendix 4. If we assume higher ‘plausible case’ values for cross price elasticity, MET value for walking and distance walked 3181 HALYs would be gained over the lifetime (95% UI 1797–4633), with AUD34.2 M in healthcare cost savings from obesity and PA related diseases (95% UI AUD17.4 M–51.3 M). The intervention would be dominant (Fig. 4). If we model only health-related costs and benefits of diseases related to obesity for the “plausible case” scenario (and omit the independent PA and injury-related effects) 2532 HALYs would be gained over the lifetime of the cohort (95% UI 1084–4098), with AUD30.3 M in obesity-related healthcare cost savings (95% UI AUD12.9 M–47.4 M). If only considering these obesity-related benefits, the “plausible case” scenario is still dominant (Fig. 4).

Using Australian recommended values for vehicle operating cost (VOC) savings, we estimate that at least AUD689 could be spent per year on replacement trip costs per new PT user as resource correction costs (Table 6). As an indication of likely replacement trip costs, a metropolitan yearly train ticket in the state of Victoria cost the equivalent of AUD1,342 in the 2010 reference year for our analysis. It should be noted however that our conservative approach to estimating VOC savings likely results in underestimation (for instance, we have not included savings related to parking costs, oil or tyre replacement costs). If we assume even a AUD5.00 parking cost per day for full-time motor vehicle commuters for 46 weeks of the year the annual breakeven for replacement PT trip costs would be AUD1839 per new PT user (i.e. potentially an overall cost saving). Evidence suggests that central business district parking rates in Australia are in fact much higher [82].

Discussion

Despite the increasing awareness that AT may positively contribute to population levels of PA with resultant public health benefits, evidence on effective and cost-effective interventions to improve rates of AT is limited. Our hypothetical estimation of potential cost-effectiveness of a macro-level fuel excise taxation intervention incorporating both PA, injury and obesity-related health benefits therefore adds to the relatively limited evidence base on the potential for ‘upstream’ interventions for obesity prevention across populations [1]. To date, only one study has investigated the impact of a fuel price increase on health [23], finding that a 20% fuel price increase in Belgium resulted in relatively modest health benefits from reduced risk of mortality from physical inactivity, and reduced mortality and morbidity from injuries and emissions (1650 DALYs averted (95% UI 1010–2330)). Our results support these findings of a positive overall health impact of an increase in fuel price, and suggest that a fuel excise taxation intervention may be cost saving when including the PA, injury and obesity-related health benefits of a resultant increase in AT but that the magnitude of results is sensitive to relatively uncertain input parameters.

Active commuting could contribute substantially towards reaching the recommended Australian adult guideline levels for PA of 150 to 300 min of moderate intensity PA per week [83]. Our conservative estimates here suggest that walking to access PT for commuting purposes could increase walking for transport on average by 90 min per week (Appendix 3). This is within the range reported in the systematic review by Rissel et al. [30] of between 8 and 33 min of additional PA per day from walking to access PT, and further highlights the valuable contribution that incidental PA through AT could make to reducing population levels of diseases associated with physical inactivity. In order to produce conservative results we also assumed that the uptake in PA occurred in those already moderately or highly physically active. If the intervention encouraged those currently inactive to walk to access PT the potential health gains could be even greater but are likely to be less sustainable.

Modelling hypothetical PA effect to BMI effect using the validated approach by Hall et al. [44] suggests that small obesity-related health benefits are also achievable through AT policies and interventions. Our estimates (Appendix 3) fall within the range of plausible estimates from published studies. For example the longitudinal study by Martin et al. [12] estimating a BMI reduction from changing from commuting by private transport to AT of −0.32 kg/m2 (95% UI -0.60 kg/m2 to −0.05 kg/m2) or the longitudinal study by Flint et al. [84] estimating that middle age adults who commuted by AT had lower BMI than car-driving commuters (−1.0 kg/m2 in men (95% UI -1.13 kg/m2 to −0.84 kg/m2), −0.7 kg/m2 in women (95% UI -0.85 kg/m2 to −0.48 kg/m2)).

Our hypothetical main scenario results suggest modest health benefits using very conservative input parameters (237 HALYs, AUD2.6 M in healthcare cost savings over the lifetime). The range of results using less conservative but still credible inputs however suggests the potential for much larger population health gains (for instance, under our ‘plausible scenario’ 3181 HALYS gained and AUD34.2 M in healthcare cost offsets). Results demonstrate that a fuel excise taxation intervention could be cost effective from an obesity prevention perspective, with the median ICER from all of our analyses falling under the AUD50,000 cost-effectiveness threshold [54]. Results also highlight the importance of improving road safety for cyclists and pedestrians, with scenarios modelling increased distance to access PT resulting in higher mortality (although lower morbidity) and all other scenarios resulting in improved traffic related morbidity and mortality.

Findings from our scoping review and hypothetical modelling study demonstrate however the limitations and difficulties of collecting and modelling evidence on the health impacts of specific population level transport interventions. Until now health impact assessments and economic evaluations of active transport interventions have relied heavily on hypothetical scenario modelling and assumptions around effect to estimate costs and consequences [9, 20]. While the information that such studies provides is useful, now there is a need for actionable, implementable and effective ways to increase rates of AT across populations. Our scoping review however demonstrates just how difficult evaluating the public health credentials of non-health sector interventions is, given that relatively little empirical evidence currently exists on the impact of fuel taxation or price on AT behaviours. The limited scope of evidence currently available on obesity-related effect is somewhat expected, given that obesity is further along the causal pathway than PA effect when considering the impact of AT on health. However we also found relatively few studies examining associations between fuel price or taxation and walking and cycling specifically, coupled with the fact that limited consensus exists around cross price elasticities of demand for PT with respect to fuel price.

Our hypothetical modelling aimed to make the best possible use of the limited evidence base as it currently stands, however a lack of more rigorous evidence of effect is a limitation of our modelling. We have tried to circumvent this to the best of our ability by using conservative estimates of parameters and providing “plausible case” scenario analyses. It should be noted however that cross price elasticities may differ between different contexts or between different socio-economic groups (for instance urban residents who are better serviced by PT may be more cross price elastic than those who are not [85]); our modelling has not been able to incorporate any of this variation or complexity at this time. Use of a more direct and observable estimate of PA or obesity effect would be preferable for our economic modelling, and this is an area where significant scope for future research exists.

Anecdotally, some countries with high prevalence of AT also have high fuel prices (for instance, the Netherlands). Evidence suggests that transport policies that promote easy and relatively cheap access to a motor vehicle result in more kilometres of daily car travel [86, 87]. Logically, fuel price may be one of several contributing factors in deciding whether to engage in AT. Whilst many other contributing factors are also likely to exist, it is clear that a better understanding of the extent to which price levers such as fuel excise taxation might contribute to reducing obesogenic environments is warranted. Whilst no single intervention is likely to improve rates of AT on its own, a better understanding of the different economic, physical, environmental, cultural and legal circumstances that might result in more AT and less private vehicle travel is required. Given that a fuel excise intervention is able to be implemented at scale and relatively easily embedded, the potential for positive health benefits should be better explored through more comprehensive research into effects on AT behaviours [2]. This is especially the case given that relatively modest population shifts to AT based on cross-price elasticities of demand for public transport with respect to fuel price as we have modelled here may result in significant obesity and PA-related benefits.

More evidence is also required on the potential sustainability of effect of specific interventions, given that individuals may alter their travel behaviours in the longer run. These longer term changes in behaviour may result in more AT – for instance, consumers may choose to move closer to their place of work so that they can walk or cycle instead of drive if fuel taxation rises. Or it may result in less travel or less AT specifically – for instance, consumers may purchase more fuel efficient or electric vehicles or change their travel patterns altogether over time if fuel taxes increase. If however consumers become desensitised to price increases over time, the intervention may also have limited effect on travel behaviours in the longer term. Given the lack of evidence of effect, our modelling assumed effect stability over the working life (18 to 64 years). This is both a limitation and a strength of our study; limiting in the sense that this assumption may overstate the stability of effect during a person’s working years but a strength in that we make no assumption that a long-term change in travel behaviour leads to a continuation of AT behaviour upon retirement.

Our results modelled potential health impacts on commuting trips, however this is also a small proportion of total trips made by motor vehicles (and potentially affected by the intervention). Travel to and from work made up only approximately one quarter of total passenger vehicle kilometres travelled in Australia in 2014 [88]. Comprehensive data on transport behaviours is relatively limited at the national level in Australia. Our results therefore potentially underestimate the health-related benefits of an increase in fuel taxation by not taking into account travel for any other purpose. Our results also do not accurately reflect the potential impact of a fuel excise intervention on those not in the workforce, such as retirees, the unemployed or children.

The efficiency of the fuel excise tax as a source of Australian government revenue currently focuses on the desirability of tax neutrality – that is, that the tax minimises distortions to consumption decisions as much as possible. The motivation for increasing fuel excise taxation to improve rates of AT would be to purposefully distort consumer choices, and so it is likely that any such intervention would be both politically and socially sensitive (Table 7). Fuel purchases make up approximately 2.97% of the average household weekly expenditure on goods and services in Australia, with middle-income households spending slightly more (approximately 3.4% for households in the second income quintile and 3.3% for households in the third income quintile) than the lowest or highest income households (2.93% and 2.49% respectively) (Appendix 6) [89]. The intervention would therefore result in greater financial impact on middle and low-income households than high-income households (Appendix 6) and households whose main source of income is from government payments would also be relatively worse off than high-income households (Appendix 6) [89]. Future scope exists for a more detailed exploration of intervention outcomes, costs and consequences by socioeconomic groups.

Due to this potential regressivity, it is clear that social offsets would be required in order to achieve political and social acceptability. The approximately AUD1.7B in revenue that the Australian Government would stand to collect on an annual basis through the increase (AUD1.5B in additional excise based on assumed intervention effect and passenger vehicle petrol consumption in 2010 [90] and AUD154M in additional GST) could be directed towards minimising regressivity and ensuring that the other factors necessary to support a switch to AT, such as PT accessibility, are available. Convenient, low-cost, affordable and good quality PT networks would act as both enablers and motivators of a move away from the current dependence on private motor vehicle travel towards more active forms of transport [91].

Whilst there have been calls for a more central role for public health in the transport planning and policy agenda [92] our findings highlight the fact that more research into potential health impacts is required in order for public health considerations to be more comprehensively considered. Whilst the body of evidence for the environmental, social and health impacts of transport planning practices has grown in recent years, there is still a significant gap in knowledge in terms of which specific interventions may provide better social, health, environmental and economic outcomes. Parallel literature has examined the potential effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of taxing other unhealthy behaviours such as drinking alcohol or sugar-sweetened beverages [93–95] and cigarettes [96, 97]. Our review demonstrates that there may be significant obesity and PA-related benefits in using fuel excise taxation as more than a neutral revenue-raising stream. Our results however highlight the need for better knowledge on the wide range of policy levers that may encourage more physically active societies.

Conclusions

Relatively limited evidence exists on the impacts of fuel price or taxation on obesity or PA-related behaviours. Exploratory modelling, using plausible estimates associated with modal switch to PT demonstrates that a fuel excise taxation intervention may provide small individual level benefits in a relatively small subset of the Australian population. If the effect is maintained over time however, these relatively small changes could lead to relatively large population level health gains. In order to be politically and socially favourable, a fuel excise intervention designed to increase rates of AT would however have to overcome significant equity and acceptability challenges. This could possibly occur through reinvestment of taxation revenues into initiatives such as better provision of alternative modes of transport. A range of intervention approaches is likely required to improve rates of AT, especially in countries with low prevalence. Implementation of such interventions is often incremental, and our paper provides valuable evidence on potential physical activity related health gains from a fiscal policy to make AT more appealing and driving less appealing to Australian drivers.

Abbreviations

- ABS:

-

Australian Bureau of Statistics

- AIHW:

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- AT:

-

Active transport

- AUD:

-

Australian dollar

- B:

-

Billion

- BITRE:

-

Bureau of Infrastructure

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- cm:

-

Centimetre

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DALY:

-

Disability adjusted life year

- EU:

-

Energy units

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- GST:

-

Goods and services tax

- HALY:

-

Health adjusted life year

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- kc:

-

Kilocalories

- kg:

-

Kilogram

- KJ:

-

Kilojoules

- km:

-

Kilometre

- LR:

-

Long-run

- LTPA:

-

Leisure time physical activity

- M:

-

Million

- ME:

-

Marginal effect

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent task

- mins:

-

Minutes

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OLS:

-

Ordinary least squares

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- pp.:

-

Per person

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PT:

-

Public transport

- QA:

-

Quality assessment

- RIS:

-

Regulatory impact statement

- s.e.:

-

Standard error

- sec:

-

Second

- SR:

-

Short-run

- st.dev.:

-

Standard deviation

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Transport and Regional Economics

- UI:

-

Uncertainty interval

- VISTA:

-

Victorian Integrated Survey of Travel and Activity

- VKT:

-

Vehicle kilometres travelled

- VMT:

-

Vehicle miles travelled

- VOC:

-

Vehicle operating cost

References

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–14.

Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–48.

Vos T, Carter R, Barendregt J, Mihalopoulos C, Veerman L, Magnus A, et al. Assessing Cost-Effectiveness in Prevention, ACE-Prevention Final Report. Melbourne: University of Queensland and Deakin University; 2010.

Sacks G, Swinburn B, Lawrence M. Obesity Policy Action framework and analysis grids for a comprehensive policy approach to reducing obesity. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):76–86.

Ananthapavan J, Sacks G, Moodie M, Carter R. Economics of Obesity—Learning from the Past to Contribute to a Better Future. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2014;11(4):4007–25.

Turrell G, Oldenburg BF, McGuffog I, Dent R. Socioeconomic determinants of health: towards a national research program and a policy and intervention agenda. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology; 1999.

Kelly P, Kahlmeier S, Götschi T, Orsini N, Richards J, Roberts N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of reduction in all-cause mortality from walking and cycling and shape of dose response relationship. Int J Behav Nutr Phy. 2014;11(1):132.

Hamer M, Chida Y. Active commuting and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2008;46(1):9–13.

Mueller N, Rojas-Rueda D, Cole-Hunter T, de Nazelle A, Dons E, Gerike R, et al. Health impact assessment of active transportation: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;76:103–14.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Social Trends 2013, Car Nation Canberra, Australia: ABS; 2014 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features40July+2013. Accessed 16 Dec 2015.

Bassett Jr DR, Pucher J, Buehler R, Thompson DL, Crouter SE. Walking, cycling, and obesity rates in Europe, North America, and Australia. J Phys Act & Heal. 2008;5(6):795–814.

Martin A, Panter J, Suhrcke M, Ogilvie D. Impact of changes in mode of travel to work on changes in body mass index: Evidence from the British household panel survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(8).

Pucher J, Buehler R, Bassett DR, Dannenberg AL. Walking and cycling to health: a comparative analysis of city, state, and international data. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1986-92.

Wanner M, Götschi T, Martin-Diener E, Kahlmeier S, Martin BW. Active transport, physical activity, and body weight in adults a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):493–502.

Saunders LE, Green JM, Petticrew MP, Steinbach R, Roberts H. What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(8).

Brown V, Moodie M, Mantilla Herrera AM, Veerman JL, Carter R. Active transport and obesity prevention – A transportation sector obesity impact scoping review and assessment for Melbourne. Australia Prev Med. 2017;96:49–66.

Di Ciommo F, Comendador J, López-Lambas ME, Cherchi E, Ortúzar JDD. Exploring the role of social capital influence variables on travel behaviour. Transp Res Part A: Policy Pract. 2014;68:46–55.

Scheepers CE, Wendel-Vos GCW, den Broeder JM, van Kempen EEMM, van Wesemael PJV, Schuit AJ. Shifting from car to active transport: A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. Transp Res Part A: Policy Pract. 2014;70(0):264-280.

Cavill N, Kahlmeier S, Rutter H, Racioppi F, Oja P. Economic analyses of transport infrastructure and policies including health effects related to cycling and walking: a systematic review. Transp Policy. 2008;15(5):291–304.

Brown V, Diomedi BZ, Moodie M, Veerman JL, Carter R. A systematic review of economic analyses of active transport interventions that include physical activity benefits. Transp Policy. 2016;45:190–208.

Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL, Bittner V, Daniels SR, Franch HA, et al. Population Approaches to Improve Diet, Physical Activity, and Smoking Habits A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(12):1514–63.

Martin A, Suhrcke M, Ogilvie D. Financial Incentives to Promote Active Travel: An Evidence Review and Economic Framework. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(6):e45–57.

Dhondt S, Kochan B, Beckx C, Lefebvre W, Pirdavani A, Degraeuwe B, et al. Integrated health impact assessment of travel behaviour: model exploration and application to a fuel price increase. Environ Int. 2013;51:45–58.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. Who's using the roads: variations in usage by drivers, Information Sheet 53. Canberra: BITRE; 2014.

Song Y, Preston J. Brand CWetbEfcsitUEaPA, 45(12), 2980–2998.. What explains travel behaviour? Evidence from case studies in the UK. Environment and Planning A. 2013;45(12):2980–98.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Monitoring of the Australian petroleum industry, Report of the ACCC into the prices, costs and profits of unleaded petrol in Australia. ACCC: Canberra; 2014.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surgery. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Lubans DR, Boreham CA, Kelly P, Foster CE. The relationship between active travel to school and health-related fitness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(5).

Daniels R, Mulley C, editors. Explaining walking distance to public transport: the dominance of public transport supply. World Symposium on Transport and Land Use Research; 2011 Whistler.

Rissel C, Curac N, Greenaway M, Bauman A. Physical activity associated with public transport use-a review and modelling of potential benefits. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2012;9(7):2454–78.

Rutherford D. Routledge Dictionary of Economics. Scotland: Taylor & Francis; 2013.

Nijkamp P, Rietveld P, Spierdijk L. A meta-analytic comparison of determinants of public transport use: methodology and application. Environ Planning B: Planning Design. 2000;27(6):893–903.

Bureau of Infrastructure Transport and Regional Economics. Elasticities Database Online Canberra, Australia: BITRE; n.d. [Available from: https://bitre.gov.au/tedb/. Accessed 12 May 2016.

Australian Taxation Office. Excise rates Canberra, Australia: ATO; 2015 [Available from: https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Excise-and-excise-equivalent-goods/. Accessed 18 Dec 2015.

Office of the Chief Economist. Australian Petroleum Statistics, Issue 237. Canberra: Office of the Chief Economist; 2016.

Breunig R, Gisz C. An exploration of Australian petrol demand: unobservable habits, irreversibility, and some updated estimates. Canberra: Australian Treasury; 2008.

Li Z, Rose JM, Hensher DA. Forecasting automobile petrol demand in Australia: An evaluation of empirical models. Transp Res Part A: Policy Pract. 2010;44(1):16–38.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census 2011 Canberra: ABS; 2011 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/data?opendocument&navpos=200. Accessed 12 Mar 2015.

Bhalla K, Ezzati M, Mahal A, Salomon J, Reich M. A risk-based method for modeling traffic fatalities. Risk Anal. 2007;27(1):125–36.

Woodcock J, Edwards P, Tonne C, Armstrong BG, Ashiru O, Banister D, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport. Lancet. 2009;374(9705):1930–43.

Xia T, Nitschke M, Zhang Y, Shah P, Crabb S, Hansen A. Traffic-related air pollution and health co-benefits of alternative transport in Adelaide, South Australia. Environ Int. 2015;74:281–90.

Maizlish N, Woodcock J, Co S, Ostro B, Fanai A, Fairley D. Health cobenefits and transportation-related reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the San Francisco Bay area. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):703–9.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Database Seattle: IHME, University of Washington; 2016 [Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/search-gbd-data?s=Transport injuries. Accessed 1 Nov 2016.

Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, Chow CC, Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):826–37.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health system expenditure on disease and injury in Australia, 2000–01. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2004.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health expenditure 2012–13. Canberra: AIHW; 2014.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Petrol prices and Australian consumers; Report of the ACCC inquiry into the price of unleaded petrol. ACCC: Canberra; 2007.

Australian Treasury. Regulation impact statement: CPI indexation of fuel excise and excise-equivalent customs duty. Canberra: Australian Treasury; 2016.

Lal A, Mantilla-Herrera A, Veerman L, Backholer K, Sacks G, Moodie M, et al. Equity and cost-effectiveness of a sugar sweetened beverage tax across socioeconomic groups. PLoS Med. In press

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6348.0 - Labour Costs, Australia, 2010–11 Canberra: ABS; 2012 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6348.02010-11?OpenDocument. Accessed 22 Mar 2016.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6302.0 - Average Weekly Earnings Australia Canberra, Australia: ABS; May 2010 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6302.0May 2010?OpenDocument. Accessed 24 Mar 2016.

Transport and Infrastructure Council. Australian Transport Assessment and Planning Guidelines Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development; 2016 [Available from: http://atap.gov.au/about/index.aspx. Accessed 7 Nov 2016.

Victoria Transport Policy Institute. Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis Victoria, Canada: VTPI; 2009 [Available from: http://www.vtpi.org/tca/. Accessed 12 Sept 16.

George B, Harris A, Mitchell A. Cost-effectiveness analysis and the consistency of decision making: evidence from pharmaceutical reimbursement in Australia (1991 to 1996). PharmacoEconomics. 2001;19(11):1103–9.

EpiGear International. Ersatz Brisbane, Australia: EpiGear International; 2016 [Available from: http://www.epigear.com/index_files/ersatz.html. Accessed 12 Feb 2016.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd ed. United States: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Courtemanche C. A silver lining? The connection between gasoline prices and obesity. Econ Inq. 2011;49(3):935–57.

Rabin BA, Boehmer TK, Brownson RC. Cross-national comparison of environmental and policy correlates of obesity in Europe. European J Public Health. 2007;17(1):53–61.

Sun LY, Lee EW, Zahra A, Park JH. Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease and Their Related Socio-Economical, Environmental and Health Behavioral Factors: Focused on Low-Middle Income Countries- A Narrative Review Article. Iranian J Public Health. 2015;44(4):435–44.

Hou N, Popkin BM, Jacobs Jr DR, Song Y, Guilkey DK, He K, et al. Longitudinal trends in gasoline price and physical activity: The CARDIA study. Prev Med. 2011;52(5):365–9.

Sen B. Is there an association between gasoline prices and physical activity? Evidence from American time use data. J Policy Analysis and Management. 2012;31(2):338–66.

Sen B, Patidar N, Thomas S. A silver lining to higher prices at the pump? Gasoline prices and teen driving behaviors. Am J Health Promotion. 2014;28(3):146–54.

Buehler R, Pucher J. Cycling to work in 90 large American cities: new evidence on the role of bike paths and lanes. Transportation. 2012;39(2):409–32.

Rashad I. Associations of Cycling With Urban Sprawl and the Gasoline Price. Am J Health Promotion. 2009;24(1):27–36.

Smith MS, Kauermann G. Bicycle commuting in Melbourne during the 2000s energy crisis: A semiparametric analysis of intraday volumes. Transp Research Part B-Methodological. 2011;45(10):1846–62.

Ryley TJ. The propensity for motorists to walk for short trips: Evidence from West Edinburgh. Transp Res Part A-Policy Practice. 2008;42(4):620–8.

Pucher J, Buehler R. Why Canadians cycle more than Americans: A comparative analysis of bicycling trends and policies. Transp Policy. 2006;13(3):265–79.

Dill J, Carr T. Bicycle commuting and facilities in major US cities: if you build them, commuters will use them. Transp Research Record. 2003;1828(1):116–23.

Götschi T, Garrard J, Giles-Corti B. Cycling as a Part of Daily Life: A Review of Health Perspectives. Transp Rev. 2015;36(1)

Petticrew M, Cummins S, Ferrell C, Findlay A, Higgins C, Hoy C, et al. Natural experiments: an underused tool for public health? Public Health. 2005;119(9):751–7.

Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, Haw S, Lawson K, Macintyre S, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1182–6.

Nowak WP, Savage I. The cross elasticity between gasoline prices and transit use: Evidence from Chicago. Transp Policy. 2013;29:38–45.

Litman T. Transit Price Elasticities and Cross-Elasticities. Canada: Victoria Transport Policy Institute; 2016.

Currie G, Phung J. Exploring the impacts of fuel price increases on public transport use in Melbourne. 29th Australasian Transport Research Conference2006.

Currie G, Phung J. Understanding Links Between Transit Ridership and Gasoline Prices Evidence from the United States and Australia. Transp Research Record. 2008;2063:133–42.

Kennedy D, Wallis I. Impact of fuel price changes on New Zealand transport. Wellington: Booz Allen Hamilton; 2007.

Luk J, Hepburn S. New review of Australian travel demand elasticities. Melbourne: Australian Road Research Board; 1993.

Holmgren J. Meta-analysis of public transport demand. Transp Res Part A-Policy Practice. 2007;41(10):1021–35.

Daniels R, Mulley C. Explaining walking distance to public transport: The dominance of public transport supply. J Transp Land Use. 2013;6(2):5–20.

Burke M, Brown AL. Distances people walk for transport. Road and Transp Research. 2007;16(3):16–29.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett Jr DR, Tudor-Locke C, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Medic Science Sports Exercise. 2011;43(8):1575–81.

Royal Automobile Club of Queensland. Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne CBD Off-street Parking Prices. Brisbane: RACQ; 2014.

Department of Health. Australia's Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health; 2014 [Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines-npa05. Accessed 17 Apr 2014.

Flint E, Cummins S. Does active commuting protect against obesity in mid-life? Cross-sectional, observational evidence from UK Biobank. Lancet. 2015;386(Supplement 2):S8.

Bastian A, Börjesson M. Peak car? Drivers of the recent decline in Swedish car use. Transp Policy. 2015;42:94–102.

Buehler R. Transport Policies, Automobile Use, and Sustainable Transport: A Comparison of Germany and the United States. J Planning Education Research. 2010;30(1):76–93.

Buehler R. Daily Travel and Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Passenger Transport Comparison of Germany and the United States. Transp Research Record. 2014;2454:36–44.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Survey of Motor Vehicle Use, Australia, 12 months ended 31 October 2014 Canberra, Australia: ABS; 2015 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/9208.012 months ended 31 October 2014?OpenDocument. Accessed 12 Oct 2015.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6530.0 Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results, 2009–10 Canberra: ABS; 2011 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/6530.0Main Features22009-10?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=6530.0&issue=2009-10&num=&view=. Accessed 1 Oct 2014.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Survey of motor vehicle use, 12 months ended 31 October 2010. Canberra: ABS; 2010.

Redman L, Friman M, Gärling T, Hartig T. Quality attributes of public transport that attract car users: A research review. Transp Policy. 2013;25:119–27.

Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Khreis H, Verlinghieri E, Rojas-Rueda D. Transport And Health: A Marriage Of Convenience Or An Absolute Necessity. Environ Int. 2016;88:150–2.

Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 373(9682):2234–46.

Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, Popkin BM, Chaloupka FJ, Thompson JW, et al. The Public Health and Economic Benefits of Taxing Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. N E J Med. 2009;361(16):1599–605.

Veerman JL, Sacks G, Antonopoulos N, Martin J. The Impact of a Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages on Health and Health Care Costs: A Modelling Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151460.

Jha P, Chaloupka FJ. The economics of global tobacco control. Brit Med J. 2000;321(7257):358–61.

Ranson MK, Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Nguyen SN. Global and regional estimates of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco control policies. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2002;4(3):311–9.

Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. Australian Road Deaths Database Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Infratructure and Regional Development; 2016 [Available from: https://bitre.gov.au/statistics/safety/fatal_road_crash_database.aspx. Accessed 31 Jan 2016.

Henley G, Harrison JE. Serious injury due to land transport accidents, Australia 2008–09. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Henley G, Harrison JE. Serious injury due to land transport accidents, Australia 2007–08. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Goodwin PB. A review of new demand elasticities with special reference to short and long run effects of price changes. J Transp Econ Policy. 1992;6(2):155–69.

Australian Institute of Petroleum. AIP Annual Retail Price Data 2015 Available from: http://www.aip.com.au. Accessed 14 Dec 2015.

Götschi T, Tainio M, Maizlish N, Schwanen T, Goodman A, Woodcock J. Contrasts in active transport behaviour across four countries: How do they translate into public health benefits? Prev Med. 2015;74:42–8.

Department for Planning and Community Development. Victorian Planning Provisions. Melbourne: Department for Planning and Community Development; 2006.

Badland H, Roberts R, Butterworth I, Giles-Corti B. How liveable is Melbourne? Conceptualising and testing urban liveability indicators: Progress to date. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne; 2015.

Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: Reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26(1):15–9.

Department of Transport Planning and Local Infrastructure. Victorian Integrated Survey of Travel and Activity (VISTA) Melbourne: State Government of Victoria; 2014 [Available from: http://www.transport.vic.gov.au/research/statistics/victorian-integrated-survey-of-travel-and-activity. Accessed 4 July 2016.

Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. Australia's commuting distance: cities and regions. Canberra: BITRE; 2015.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Environmental Issues: Waste Management, Transport and Motor Vehicle Usage, Mar 2012 Canberra: ABS; 2012 [Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4602.0.55.002Mar 2012?OpenDocument. Accessed 25 June 2014.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Brown, Moodie, Mantilla Herrera and Carter are researchers within the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funded Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) on Obesity Policy and Food Systems (Grant no. 1041020). Brown receives a Deakin University Postgraduate Research Scholarship. Mantilla Herrera receives a University of Queensland I-tuition scholarship. Cobiac is supported by a Sidney Sax public health fellowship from the NHMRC (#1036771). The opinions, analysis and conclusions in this article are those of the author/s and are not necessarily endorsed by the NHMRC or the author/s institutions.

Availability of data and materials

The CRE Obesity Model will be made publicly available through a third-party online repository at the completion of the project (scheduled for October 2017). Until such time as the project allows for the public sharing of the model, the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

VB formulated the major ideas for the paper and study inclusion criteria, and conducted the literature search and quality assessment. RC verified the literature search strategy and study inclusions. VB wrote the first draft of the main document and appendices. AM provided the base economic model. VB and LC added injury effect into the base model. VB undertook the modelling, with LC checking model inputs and parameters. RC, MM, LC and AM reviewed and edited all sections. All authors (VB, MM, LC, AM, RC) read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics exemption has been granted from Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2016–037).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Search strategies.

Tables provide a summary of search strategies for the scoping review.

To be considered for inclusion studies needed to:

-

1.

Be written in the English language in any year;

-

2.

Be published as an academic paper in a peer review journal;

-

3.

Be a primary study, not a review;

-

4.

Report on (i) an obesity-related effect, or (ii) a PA-related effect of fuel taxation or price. Obesity-related effect was defined as a change in an adiposity related outcome such as weight, waist circumference or BMI. PA-related effect was defined as a change in leisure or utilitarian PA, walking or cycling.

Studies reporting on associations between fuel taxation or price and a variable representing the demand for motor vehicles (for example, motor vehicle ownership or distance travelled) were excluded because associations do not necessarily reflect a shift to more AT, but may better reflect a change in discretionary or other travel behaviours (for example, trip purpose or timing). The reference lists of included studies were also searched.

Appendix 2

Tables provide details on the strength of evidence assessment.

Appendix 3

Table provides data parameters for the intervention effect estimate.

Appendix 4

Parameters for uncertainty analysis.

Tables provide summaries of one-way and “plausible case” sensitivity analyses input parameters.

Appendix 5

Table provides summary of results of quality assessment of included studies in scoping review.

Appendix 6

Table provides summary of potential equity effects of the proposed intervention.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, V., Moodie, M., Cobiac, L. et al. Obesity-related health impacts of fuel excise taxation- an evidence review and cost-effectiveness study. BMC Public Health 17, 359 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4271-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4271-2