Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to examine the association between socioeconomic position and the domains of physical activity connected with work, travel, and recreation in Japanese adults.

Methods

A total of 3269 subjects, 1651 men (mean ± standard deviation; 44.2 ± 8.1 years) and 1618 women (44.1 ± 8.1 years), responded to an Internet-based cross-sectional survey. Data on socioeconomic (household income, educational level) and demographic variables (age, size of household, and household motor vehicles) were obtained. To examine the associations between socioeconomic position and physical activity, logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI) for “active” domains of physical activity.

Results

Men with a household income of ≥7 million yen had significantly lower work-related physical activity than the lowest income group (OR 0.51; 95 % CI, 0.35–0.75), but significantly greater travel-related (OR 1.37; 1.02–1.85), recreational (OR 2.00; 1.46–2.73) and total physical activity (OR 1.56; 1.17–2.08). Women with a household income of ≥7 million yen had significantly greater recreational physical activity (OR 1.43; 1.01–2.04) than the lowest income group. Their total physical activity was borderline significant, with slightly more activity in the high-income group (OR 1.36; 1.00–1.84), but no significant differences for work- and travel-related physical activity. Men with higher educational level (4-year college or higher degree) had significantly lower work-related (OR 0.62; 0.46–0.82), and greater travel-related physical activity (OR 1.33; 1.04–1.71) than the lowest educated group, but there were no significant differences in recreational and total physical activity. Women with a 4-year college or higher degree had significantly greater travel-related physical activity than the lowest educated group (OR 1.49; 1.12–1.97), but there were no significant differences in any other physical activity. There was no relation between working full time and physical activity in men, but women working full-time have significantly lower and not higher travel related physical activity. (OR 0.75; 0.59–0.96).

Conclusions

This study suggests that lower socioeconomic position is associated with more work-related physical activity, and less travel-related, recreational and total physical activity, and that this was more pronounced in men than in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical activity reduces mortality and the incidence of non-communicable diseases [1, 2]. However, a large proportion of the population in Japan and in many other countries remains physically inactive [3]. Promotion of physical activity is therefore a major public health concern globally. In Japan, the number of walking steps per day has decreased over time from around 1998–2000 [4], and a health promotion policy is needed to increase physical activity again. To increase participation in physical activity, it is necessary to understand the factors that influence this, and to design relevant policies and effective interventions based on that understanding.

Socioeconomic position (SEP), including for example, household income and educational level, is a determining factor of health status, and it is particularly important to promote a healthy lifestyle in low SEP populations [5]. In previous studies, lower SEP was associated with poorer health status and unhealthy behaviour among Japanese adults [6–8].

Studies that examined the association between SEP and total physical activity have, however, been inconsistent [9–13]. In a systematic review of European studies of the association between SEP and physical activity across the domains of work, travel and recreation, lower SEP was associated with greater occupational physical activity, but with less recreational physical activity [14]. It is also important to examine the association between SEP and domains of physical activity (DPA) such as work, travel, and recreation, to identify lifestyle factors that can be targeted to increase physical activity [15].

There is no comprehensive study examining the association between SEP and DPA among Japanese subjects. Japanese culture and lifestyles are different from those in Europe, so examining the relevant associations between socioeconomic position and physical activity in each domain of life in Japan is important for improving health promotion activity [16]. The association between SEP and health behaviours varies according to gender [7]; there are, however, few studies that have examined this [14]. The aim of this study was therefore to examine the association between SEP and DPA in Japanese men and women.

Methods

Participants and data collection

The data sample for this study consisted of 3269 respondents recruited to an Internet-based cross-sectional survey, which was conducted through a Japanese Internet research company, which had approximately 106,281 voluntarily-registered subjects across Japan in 2014. The company had access to detailed sociodemographic information and was able to target specific attributes. The set sample size and attributes for this study were: approximately 3000 adults, 30–59 years of age, stratified by age, gender, and household income distributions in line with the basic Japanese resident register for 2013, the 2012 Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions in Japan [17, 18]. A total of 8284 potential respondents were randomly and blindly selected and subsequently invited via e-mail to participate in the Internet-based survey. There were 3269 respondents, a 39.5 % response rate. Of these, 137 were excluded because of missing data, leaving 3132 participants (final response rate: 37.8 %). The invitation e-mail contained a link directing the potential respondents to a protected area of the website where the questionnaire was located. They could then log on using their own login identity and password. As an incentive for participation, the respondents were offered reward points valued at 100 yen (1 U.S. dollar was approximately equivalent to 102 yen and €1 to 140 yen at the time). All the respondents voluntarily completed a demographic data information form and clicked on the “agree” button at the end of an online informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee, Waseda University. The study received prior approval from the Ethics Committee, Waseda University, Japan.

Measurements

Physical activity

The Global Physical Activity Questionnaire version 2 (GPAQ v2) is a questionnaire that was developed as a modification of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire for use in multi-ethnic settings by the World Health Organization [19]. GPAQ v2 was used to estimate the total weekly quantity (in minutes) of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity across three separate domains (work, travel, and recreation) lasting at least 10 min per session.

Previous study has shown that GPAQ has good test-retest reliability and validity [20]. Translation of the original content of GPAQ into Japanese, followed by back translation into English ensured the reliability of the questionnaire. No changes were made to the original content and wording of the questionnaire.

Demographic variables and SEP indicator

The demographic variables obtained from the research company included gender (men and women), age (categorized as 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 years), size of household (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 or more people) and the number of household motor vehicles (none, 1 and 2 or more). Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported body height and body weight using the equation BMI = body weight in kg/body height in m2. The socioeconomic variables included household income (categorized as <3 million yen, 3–7 million yen, ≥7 million yen), educational level (junior high and high school graduation, 2-year college degree or equivalent, and 4-year college or higher degree), and employment status (non full time worker or full time worker).

Data analysis

Data from 1579 men and 1553 women who provided complete information for the study variables were analysed. All the analyses were stratified by gender. Means, standard deviations and relative frequencies (%) were used to describe the subjects. To examine the associations between SEP and DPA, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI) for “active” physical activity. The dependent variable was physical activity. For the analysis, each DPA was categorised into “active” (physical activity performed at least 10 min duration during one or more days a week) or “inactive” (physical activity not performed at least 10 min duration during a week). And, total physical activity was categorised by WHO physical activity recommendation (active: ≥ 150 min/week, inactive: < 150 min/week) [21]. The independent variables included in the multiple binomial logistic regression analyses were household income, educational level and employment status with adjustment for age, size in household, BMI, and household motor vehicle ownership. Significance was set at a level of p <0.05. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan, 2012).

Results

Basic characteristics of the respondents

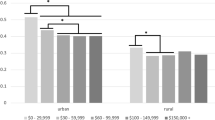

Table 1 presents the demographic and socioeconomic data of the participants. A total of 3132 subjects, 1579 men (50.6 %) and 1553 women (49.4 %), participated in this study. The proportion in each class for age, size of household, and BMI were significantly different for men and women. The proportion who reported each class of household income (<3, 3–7 and ≥7 million yen) was 31.7, 40.7, and 27.5 % in men, and 30.9, 41.7 and 27.4 % in women. The proportion who reported each educational level class (junior high and high school graduation, 2-year college degree or equivalent, and 4-year college or higher degree) was 26.1, 16.3 and 57.6 % in men, and 26.7, 39.2 and 34.1 % in women. The proportion reporting each employment status (non full time worker or full time worker) was 23.7 and 76.3 % in men, 70.2 and 29.8 % in women. Men showed significantly higher work-related, recreational, and total physical activity than women.

Household income and physical activity

Table 2 shows the associations between physical activity and household income in men and women, with adjustment for age, size of household, body mass index, household motor vehicle ownership, and educational level. Men with a household income of over 7 million yen had significantly lower work-related physical activity than the lowest income group (OR 0.51; 95 % CI 0.35–0.75), but significantly greater travel-related (OR 1.37; 95 % CI 1.02–1.85), recreational (OR 2.00; 95 % CI 1.46–2.73), and total physical activity (OR 1.56; 95 % CI 1.17–2.08). Women with a household income of over 7 million yen had significantly greater recreational physical activity than the lowest income group (OR 1.43; 95 % CI 1.01–2.04), but there was no significant difference regarding work- (OR 0.81; 95 % CI 0.52–1.25) or travel-related (OR 1.13; 95 % CI 0.83–1.53) physical activity. Total physical activity was borderline significant, with slightly greater activity in the high-income group (OR 1.36; 95 % CI 1.00–1.84).

Educational level and physical activity

Table 2 also shows the associations between physical activity and educational level in men and women, with adjustment for age, size of household, body mass index, household motor vehicle ownership, and household income. Men with a 4-year college or higher degree had significantly lower work-related physical activity than the lowest educated group (OR 0.62; 95 % CI 0.46–0.82), and higher travel-related activity (OR1.33; 95 % CI 1.04–1.71), but there were no significant differences in recreational (OR 1.29; 95 % CI 0.98–1.70) or total physical activity (OR 0.99; 95 % CI 0.78–1.26). Women with a 4-year college or higher degree had significantly greater travel-related activity than the lowest educated group (OR 1.49; 95 % CI 1.12–1.97), but there were no significant differences in work-related (OR 0.94; 95 % CI 0.64–1.37), recreational (OR 1.35; 95 % CI 0.97–1.88), or total physical activity (OR 1.19; 95 % CI 0.90–1.57).

Employment status and physical activity

Table 2 also shows the associations between physical activity and employment status in men and women, with adjustment for age, size of household, body mass index, household motor vehicle ownership, and household income. Full-time working in men was not significantly related to physical activity, but women who worked full time had significantly lower travel-related physical activity (OR 0.75; 95 % CI 0.59–0.96).

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the gender-linked association between SEP and physical activity in Japanese adults. In accordance with the previous systematic review of European studies [14], this study found various associations between SEP and different DPA in Japanese adults. There were also differences in these associations between the sexes. It is therefore important to take into account SEP, DPA, and gender when formulating proposals for the promotion of physical activity.

In work-related physical activity, the men with higher household income or educational status were less active than men with lower SEP. However, the relationship between SEP and work-related physical activity was not significant in women. Previous European studies had shown a consistent association between SEP and work-related physical activity in both sexes [14]. This difference in this study may be related to a difference in the assessment of work-related physical activity. Assessment of work-related physical activity in this study included housework, while previous studies had excluded this [22, 23]. Since 70.2 % of women in this study reported that they worked part-time (data not shown), most work-related physical activity for women in this study was likely to be housework. This could account for the lack of association between SEP and work-related physical activity in women.

In travel-related physical activity, the men with higher household income or educational status were more active than men with lower SEP. Also, the women with higher educational status were more active than women with lower educational status. However, full time employed women were less travel-related physically active than non-full time employed women The European review found no consistent association between SEP and travel-related physical activity in either sex [14]. In a Japanese study, Ishii et al. [24] reported that higher SEP was associated with more active commuting modes (e.g., walking, bicycle, public transport). In Japan, previous studies reported a significant association between the neighbourhood environment and travel-related physical activity [16, 24]. The significant direct association between SEP and travel-related physical activity found in this study might therefore be affected by environmental factors. However, the reasons for the differences between men and women in this study are unknown, and further study is therefore required.

In recreational-related physical activity, both men and women who showed high household income were more active than lower household income workers. There was also a direct association between SEP and recreational physical activity in both sexes in the European review [14], and earlier Japanese studies [7, 25]. Leslie et al. reported that high SEP residents had easier access to parks than lower SEP residents and used them more [26]. Psychological factors such as self-efficacy and self-control, and social factors, such as social interaction, mediate the relationship between SEP and recreational physical activity [27–29]. This study did not indicate why there was no significant association between educational level and recreational physical activity, though there was a trend towards an association in both sexes.

In total physical activity, both men and women who showed high household income were more active than lower household income workers. Previous Japanese studies have reported inconsistent associations between SEP and total physical activity [9–13]. Although high household income was associated with less work-related physical activity, this appears to be more than compensated for by greater travel and recreational physical activity.

This study had two major limitations. First, physical activity was not measured using an objective instrument. Objective measurements (using, for example, a pedometer) are generally recommended, but cannot provide data about physical activity in each domain. A self-report questionnaire was therefore used in this study to examine the association between SEP and the different domains of physical activity. It is therefore possible that the validity and reliability of GPAQ v2 is lower than an objective measure. However, GPAQ has been standardized and is used worldwide [19, 30].

Secondly, this study may have a sampling bias. Participants voluntarily registered with the Internet research company [31], and many Internet survey registrants expect an incentive from the research company. It is therefore possible that the study subjects were not representative of the local general population. This study may also have shown selection bias, since the response rate was lower in women, people who were younger and those with a lower income.

Conclusions

Although this study has some limitations, our results suggest that both men and women with higher household income are more active in recreational-related and total physical activity than the both sexes with lower income. However, the relationships between SEP and work or travel-related physical activities are different in gender. To increase physical activity in Japanese adults with lower SEP, it will therefore be important to focus on increasing travel and recreational physical activity. In a follow-up study, the mechanism of the association between SEP and DPA will be examined.

References

Samitz G, Egger M, Zwahlen M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(5):1382–400.

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29.

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–57.

Inoue S, Ohya Y, Tudor-Locke C, Tanaka S, Yoshiike N, Shimomitsu T. Time trends for step-determined physical activity among Japanese adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(10):1913–9.

World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: social determinants of health discussion paper 2. [http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf].

Kagamimori S, Gaina A, Nasermoaddeli A. Socioeconomic status and health in the Japanese population. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2152–60.

Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Socioeconomic pattern of smoking in Japan: income inequality and gender and age differences. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(5):365–72.

Nishi N, Makino K, Fukuda H, Tatara K. Effects of socioeconomic indicators on coronary risk factors, self-rated health and psychological well-being among urban Japanese civil servants. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1159–70.

Ishii K, Shibata A, Oka K. Meeting physical activity recommendations for colon cancer prevention among Japanese adults: prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(7):907–15.

Liao Y, Harada K, Shibata A, Ishii K, Oka K, Nakamura Y, et al. Association of self-reported physical activity patterns and socio-demographic factors among normal-weight and overweight Japanese men. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:278.

Shibata A, Oka K, Harada K, Nakamura Y, Muraoka I. Psychological, social, and environmental factors to meeting physical activity recommendations among Japanese adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:60.

Inoue S, Ohya Y, Odagiri Y, Takamiya T, Suijo K, Kamada M, et al. Sociodemographic determinants of pedometer-determined physical activity among Japanese adults. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(5):566–71.

Takao S, Kawakami N, Ohtsu T. Occupational class and physical activity among Japanese employees. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(12):2281–9.

Beenackers MA, Kamphuis CB, Giskes K, Brug J, Kunst AE, Burdorf A, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in occupational, leisure-time, and transport related physical activity among European adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:116.

Kruger J, Ham SA, Berrigan D, Ballard-Barbash R. Prevalence of transportation and leisure walking among U.S. adults. Prev Med. 2008;47(3):329–34.

Inoue S, Ohya Y, Odagiri Y, Takamiya T, Ishii K, Kitabayashi M, et al. Association between perceived neighborhood environment and walking among adults in 4 cities in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(4):277–86.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Basic resident register 2013. [http://www.soumu.go.jp/menu_news/s-news/01gyosei02_02000055.html] (in Japanese).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Comprehensive survey of living conditions 2012. [http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa12/index.html] (in Japanese).

World Health Oraganization. Global physical activity surveillance. [http://www.who.int/chp/steps/GPAQ/en/].

Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(6):790–804.

World Health Oraganization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979_eng.pdf?ua=1].

Wang Y, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, Antikainen R, Mahonen M, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity in relation to heart failure among Finnish men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(14):1140–8.

Van Tuyckom C, Scheerder J. Sport for all? Insight into stratification and compensation mechanisms of sporting activity in the 27 European Union member states. Sport Educ Soc. 2010;15(4):495–512.

Ishii K, Shibata AI, Oka K, Inoue S, Shimomitsu T. Association of built-environment and active commuting among Japanese adults. Jpn J Phys Fit Sport. 2010;59(2):215–24 (in Japanese).

Saito Y, Oguma Y, Inoue S, Tanaka A, Kobori Y. Environmental and individual correlates of various types of physical activity among community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly Japanese. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(5):2028–42.

Leslie E, Cerin E, Kremer P. Perceived neighborhood environment and park use as mediators of the effect of area socio-economic status on walking behaviors. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(6):802–10.

Murray TC, Rodgers WM, Fraser SN. Exploring the relationship between socioeconomic status, control beliefs and exercise behavior: a multiple mediator model. J Behav Med. 2012;35(1):63–73.

Lehto E, Konttinen H, Jousilahti P, Haukkala A. The role of psychosocial factors in socioeconomic differences in physical activity: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41:553–9.

Mulder BC, de Bruin M, Schreurs H, van Ameijden EJ, van Woerkum CM. Stressors and resources mediate the association of socioeconomic position with health behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:798.

Cleland CL, Hunter RF, Kee F, Cupples ME, Sallis JF, Tully MA. Validity of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) in assessing levels and change in moderate-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1255.

Yasunaga H, Ide H, Imamura T, Ohe K. [Medical research using internet questionnaire in Japan]. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2006;53(1):40–50 (in Japanese).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (No. 25560357) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Global COE Program “Sport Sciences for the Promotion of Active Life” from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MM, KH, and TA participated in the design of this study. MM performed the data mining and the statistical analysis, and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. KH contributed to the statistical analysis and editing of the manuscript. TA assisted in the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsushita, M., Harada, K. & Arao, T. Socioeconomic position and work, travel, and recreation-related physical activity in Japanese adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 15, 916 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2226-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2226-z