Abstract

Background

The long-term effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) adults with residual symptoms needs to be verified across multiple dimensions, especially with respect to maladaptive cognitions and psychological quality of life (QoL). An exploration of the mechanisms underlying the additive benefits of CBT on QoL in clinical samples may be helpful for a better understanding of the CBT conceptual model and how CBT works in medicated ADHD.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial including 98 medicated ADHD adults with residual symptoms who were randomly allocated to the CBT combined with medication (CBT + M) group or the medication (M)-only group. Outcomes included ADHD-core symptoms (ADHD Rating Scale), depression symptoms (Self-rating Depression Scale), maladaptive cognitions (Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire and Dysfunctional Attitude Scale), and psychological QoL (World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version-psychological domain). Mixed linear models (MLMs) were used to analyse the long-term effectiveness at one-year follow-up, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed to explore the potential mechanisms of CBT on psychological QoL.

Results

ADHD patients in the CBT + M group outperformed the M-only group in reduction of ADHD core symptoms (d = 0.491), depression symptoms (d = 0.570), a trend of reduction of maladaptive cognitions (d = 0.387 and 0.395, respectively), and improvement of psychological QoL (d = − 0.433). The changes in above dimensions correlated with each other (r = 0.201 ~ 0.636). The influence of CBT on QoL was mediated through the following four pathways: 1) changes in ADHD core symptoms; 2) changes in depressive symptoms; 3) changes in depressive symptoms and then maladaptive cognitions; and 4) changes firstly in depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and then ADHD core symptoms.

Conclusions

The long-term effectiveness of CBT in medicated ADHD adults with residual symptoms was further confirmed. The CBT conceptual model was verified in clinical samples, which would be helpful for a deeper understanding of how CBT works for a better psychological QoL outcome.

Trial registration

ChiCTR1900021705 (2019-03-05).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common, chronic neurodevelopmental disorder [1]. Up to 65% of children with ADHD continue to have persistent ADHD symptoms in adulthood [2], and symptoms and associated functional impairments have been shown to fluctuate throughout adulthood in approximately 90% of cases [3]. The prevalence of adult ADHD was approximately 2.5% [4]. Individuals with a diagnosis of ADHD have a greater risk of experiencing depressive symptoms, and difficulties in academic, school, work, marriage, and interpersonal relationships across their lifespan, leading to poor functional outcomes [5, 6].

Psychological quality of life (QoL), which refers to an individual’s subjective and objective evaluations of life functioning and satisfaction, is now more considered as a measure of the long-term outcomes for ADHD [7, 8], rather than merely focusing on changes in the core symptoms [9]. The available evidence still argues for the real benefits of medication in the functional improvement of ADHD adults [10,11,12] since patients with stable ADHD medication still reported problems with interpersonal and functional impairments [13]. Thus, the importance of nonpharmacological interventions in the treatment of ADHD has been highlighted in addition to pharmacotherapies for better treatment adherence [14] and long-term functional outcomes for adults with ADHD [15].

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has the most empirical support among nonpharmacotherapies in medicated ADHD adults with residual symptoms [16,17,18,19]. Based on the CBT conceptual model of ADHD, QoL impairment might be accounted for by both ADHD core symptoms and the related depressive symptoms since patients received more negative feedback from others caused by core symptom impairments [20]. CBT might improve QoL through two main pathways: the decrease in ADHD core symptoms by acquiring and using compensatory strategies and the release of depressive symptoms via cognition reframing. Besides, the decrease in ADHD core symptoms could also be obtained via the release of depressive symptoms since compensatory strategies could be better used with fewer emotional distress. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CBT in reducing ADHD core symptoms, depression, and improving QoL in adults with ADHD [18, 21, 22], and the important role of depressive symptoms on QoL has also been emphasized [23,24,25]. However, the potential mechanism based on the CBT conceptual model still needs to be verified in clinical samples, which would benefit from a deeper understanding of how CBT works on the QoL outcome through maladaptive cognitions, depressive symptoms, and ADHD core symptoms, especially on the longer-term impact.

One important way to investigate mechanisms of change is mediation [26], pointing to an intervening variable that may explain the association between the dependent (outcome) and independent (treatment) variables [27]. Most mediating studies have focused on emotional disorders of CBT, and found that the changes in QoL were partially mediated by reductions in symptom changes such as depression [28], sleep [29], and irritable bowel syndrome [30]. However, few studies explored the mediating role in ADHD samples.

Our previous studies confirmed the effectiveness of CBT on ADHD core symptoms, anxiety and depression, maladaptive cognitions, and QoL [22, 31, 32], but long-term effectiveness still needs further confirmation. Additionally, we hope to further explore the mechanism of CBT to determine how CBT works in adult ADHD with residual symptoms, although they have been prescribed with stable medication. Thus, our study aimed to explore (1) the long-term effectiveness of CBT on ADHD core symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, emotional symptoms, and QoL in medicated adult ADHD with residual symptoms, and (2) the possible mechanism of the effect of CBT on QoL through changes in ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, and related maladaptive cognitions using structural equation mediation model. Based on previous studies, the CBT conceptual model, and our research experiences, we hypothesized that (1) CBT could further reduce ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, and related maladaptive cognitions in long-term follow-up, and QoL could be improved; and (2) the change in psychological QoL would be affected indirectly by CBT through ADHD core symptoms, and through depressive symptoms and then related maladaptive cognitions.

Methods

This study analysed the one-year follow-up data from a published randomised controlled trial (RCT) protocol [33] that compared the effectiveness of CBT between CBT combined with medication (CBT + M) group and medication (M)-only group. The protocol of the original study was registered at Peking University Sixth Hospital, and the registration identification number is ChiCTR1900021705. This study received ethics approval from the ethics committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital, and all participants signed informed consent forms.

Participants

Participants were outpatients of Peking University Sixth Hospital and individuals recruited from the Internet from March 2019 to November 2019. The outpatients were transferred by psychiatrists in the outpatient clinic. Besides, our research information was also published on the website. Interested participants underwent a screening through recruitment links, and those who initially met the diagnostic criteria through self-assessment screening were then evaluated for eligibility in the outpatient clinic, the same as with those transferred by psychiatrists.

All participants received a diagnostic interview by psychiatric physicians via Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID) [34]. The symptoms during childhood were confirmed based on the recall of the participants as well as the reports of parents or other major caregivers. The key inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1)

Aged 18–45 years old with a diagnosis of adult ADHD through Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview [34].

-

2)

Stable use of medication (drug fluctuations < 10% for at least 1 month) [35], either methylphenidate hydrochloride controlled-release tablets (Concerta®) or atomoxetine hydrochloride (Strattera®).

-

3)

With residual symptoms since they were scaled with Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-S) ≥ 3 (mildly ill or above).

The key exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1)

Patients with current severe mental disorders, including psychotic disorders, current mania episodes of bipolar disorder, severe depressive episodes with psychotic symptoms or high risk of suicide/self-injury, severe panic disorder, substance abuse, and antisocial personality disorder.

-

2)

Those with a full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) < 80.

-

3)

Those with suicide risk.

-

4)

Those with unstable physical conditions (such as diabetes, angina pectoris, hypertension, or active hepatitis).

-

5)

Prior or present participation in other psychological therapies.

Patients who attended < 7 times or those who switched to other treatments were considered dropouts from the study.

Procedures

Participants underwent the assessments at the clinic at three time points, including at baseline, post-treatment, and one-year follow-up. After each time of assessment, the participants would get their multidimensional evaluation report, and the participants of the M-only group were also compensated for an opportunity to participate in group CBT after their one-year follow-up. All participants recruited were under assessment by psychiatrists blinded to treatment assignment, and an independent statistician conducted the randomization. The assessors were postgraduate students of psychiatry who had received unified training to use all the measurement tools, and the consistency was rated.

The flowchart of participants from baseline to one-year follow-up is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 372 subjects interested in the study were contacted, of whom 193 (51.88%) underwent the baseline assessment, and the remaining 98 participants who met the inclusion criteria were randomized to either the CBT + M group (n = 49) or the M-only group (n = 49). The CBT + M group engaged in 12 weeks of group CBT, and the M-only group waited and received basic clinical management. One-year follow-up data were obtained from 87.76% (43/49) of the CBT + M group and 89.80% (44/49) of the participants in the M-only group.

Measures

Diagnostic interview and intelligence quotient (IQ) evaluations

Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID) [34] was used to assess ADHD diagnosis, and Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV Axis-I and Axis-II [36] were used to assess comorbid disorders at the baseline assessment. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised in China (WAIS-RC) [37] was used to estimate the full-scale IQ (FIQ).

ADHD core symptoms

The self-reported ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) [38] was used to evaluate the ADHD core symptoms. The higher the total score, the more severe the core-symptom impairment.

Depressive symptoms

The Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) [39] was used to assess depressive severity. A higher score indicates more severe depressive symptoms.

Maladaptive cognitions

The Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ) [40] was used to evaluate the frequency of spontaneous negative thoughts, and the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) [41] was used to measure individuals’ depressogenic assumptions or beliefs. A higher score indicates more maladaptive cognitions related to depressive symptoms.

Quality of life

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) [42, 43] was used to evaluate the degree of life satisfaction in four dimensions. We used the psychological domain score to estimate the psychological quality of life (QoL-psychological domain). Higher scores indicate higher levels of QoL.

Interventions

The 12-week group CBT program had a detailed introduction in the protocol [33]. The modules on organization and planning, coping with distractibility, restructuring maladaptive cognitions, and dealing with procrastination were mainly discussed. All participants attended CBT organized by the same psychotherapy team who had received systematic training and regular supervision to deliver the program. Each CBT group consisted of 7 to 12 patients, a leader, and a co-leader who cooperated together. The weekly CBT continued for 12 weeks and involved one 120-minute session each week. Each treatment session started with a review of homework and group-based reflection on ADHD and related symptoms, and then new skills learning and discussion were performed, and homework was arranged.

The M-only group received basic clinical management based on their own needs in the outpatient clinic, including medical consultation and nonpharmacological consultation not related to CBT treatment.

Due to the study design, the participants were asked to maintain stable use of medication during follow-up, but best clinical practices were followed, which resulted in some changes. Thus patients were asked to report their use of medication at each time estimation.

Statistical analyses

First, independent two-sample t-tests for continuous data and χ2 tests for categorical data were performed to compare the baseline variables. Then, mixed linear models (MLMs) were conducted to analyse the effects between the two groups at the one-year follow-up including dimensions of ADHD core symptoms (ADHD-RS total score), depressive symptoms (SDS score), maladaptive cognitions (ATQ and DAS total scores), and psychological QoL (QoL - psychological domain score). Group, time and group×time interactions were used as fixed effects, and the random effect included the intercept term and slope overtime. If a significant group×time interaction was observed, post hoc pairwise comparisons were then conducted to assess the changes between assessment points within each group. The statistics were based on an intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis, and multiple imputations (data were imputed 5 times) were conducted in the original dataset to address the missing data [44].

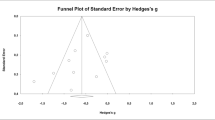

The changes in ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and QoL at one-year follow-up from baseline were then collected. To explore the mechanism of CBT, Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the correlation among score changes in above dimensions both in the CBT + M and M-only groups. Irrelevant, weak, moderate, and strong correlations (r) were defined as r values of 0–0.09, 0.10–0.30, 0.30–0.50, and 0.50–1.00, respectively. Structural equation mediation model analyses (SEM) were then performed using the R package lavaan [45] with the R software (Version 4.2.2) to test the influence of CBT on changes in psychological QoL via ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, and maladaptive cognitions. The mediation analysis was controlled for baseline dimension indicators (such as age, gender, years of education, FIQ, etc.) if differences between groups were found. Model fit was assessed using the confirmatory fit index (CFI) [46], root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) [47]. CFI > 0.95 and RMSEA < 0.06 are viewed as supporting good model fit.

Results

Baseline characteristics

No significant differences in the demographic background data were found between the CBT + M and the M-only groups (see Table 1).

Treatment adherence

During the 12-week CBT, the participants attended a mean of 10.76 ± 1.38 sessions. The dropout rate did not differ significantly between the CBT + M group vs the M-only group after 12 weeks of CBT (CBT + M: 10.20%, M: 4.08%, χ2 = 1.385, p = 0.436) and at one-year follow-up (CBT + M: 12.24%, M: 10.20%, χ2 = 0.102, p = 0.749) (Fig. 1).

In the CBT + M group, one patient changed the use of medication from Strattera® to a combination of Strattera® and Concerta®. One patient stopped taking the medication after the 12-week treatment and 4 of them discontinued the medication at the one-year follow-up. In the M-only group, one participant stopped using the medication after the 12-week treatment and one of them discontinued the medication at the one-year follow-up. All patients completed the follow-up assessments whether or not they took medication regularly. Analyses that both included and excluded the follow-up data from these participants were conducted, and no differences in results were found, so the final results contained the whole data.

Long-term effectiveness

Table 2 displayed the means, SEs, and differential treatment effects of the CBT + M group versus the M-only group on ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and psychological QoL from baseline to one-year follow-up.

First, patients in the CBT + M group had a significantly greater decrease in self-reported ADHD-RS scores at the one-year follow-up than those in the M-only group (group×time interaction: d = 0.491, 95% CI = [0.088, 0.892]). Post hoc pairwise comparisons within each group indicated that the self-reported ADHD-RS total score decreased significantly (p < 0.001) in the CBT + M group but remained stable in the M-only group (p = 0.144).

Second, the CBT + M group outperformed the M-only group in the decrease of SDS score (group×time interaction: d = 0.570, 95% CI = [0.164, 0.973]) and improvement of WHOQOL-BREF psychological domain score (group×time interaction: d = − 0.433, 95% CI = [− 0.827, − 0.022]). Post hoc pairwise comparisons within each group indicated that the SDS scores (p < 0.001) decreased significantly, and the WHOQoL-psychological domain score (p = 0.012) increased significantly in the CBT + M group. Patients in the CBT + M group also achieved significant improvements in ATQ (t = 2.507, p = 0.014) and DAS (t = 3.263, p = 0.002) scores from baseline at one-year follow-up, although the group×time interactions were not statistically significant (p = 0.058 and 0.054, respectively). Patients in the M-only group maintained stable scores (p > 0.05) in the above dimensions.

Correlations between changes in ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and psychological QoL

Pearson’s correlation analyses were used to evaluate the relationships in adults with ADHD after controlling for sex, age, and FIQ. Positive correlations between changes in ADHD-RS and SDS, ATQ, and DAS (r = 0.201 ~ 0.472, p < 0.01) were found, and the correlations were small to moderate. Changes in SDS score were positively correlated with changes in ATQ and DAS score (r = 0.365 ~ 0.541, p < 0.001), and the WHOQOL-BREF-psychological domain score (r = 0.500 in the CBT + M group and 0.499 in the M-only group, p < 0.001). The above correlations presented similar both in the CBT + M group and in the M-only group. The correlations between changes in ADHD-RS total score and WHOQOL-BREF psychological domain score in the M-only group were strong (r = 0.537) and moderate in the CBT + M group (r = 0.317) (Table 3).

Mediation analyses

All variables of ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, and maladaptive cognitions were selected. The independent variable was CBT intervention, and the dependent variable included change in QoL-psychological domain score, mediators included changes in ADHD-RS total score, SDS, and maladaptive cognitions (ATQ and DAS).

The structural model for CBT on QoL and maladaptive cognitions showed a good fit (χ2 (df = 5.000) = 7.999, p = 0.156, CFI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.035, SRMR = 0.025). The model showed that CBT would influence changes in WHOQOL-psychological domain score through the following pathways: 1) the change in ADHD-RS total score (β = 0.032, 95% CI = [0.399, 1.854], p = 0.004); 2) the change in SDS score (β = 0.054, 95% CI = [0.782, 2.795], p < 0.001); and 3) the change in SDS score and then the change in maladaptive cognitions (β = 0.054, 95% CI = [0.966, 3.052], p < 0.001). Besides, CBT would also influence the change in ADHD-RS total score through the change in SDS score and then the change in maladaptive cognitions, thereby affecting the change in WHOQOL-psychological domain score (β = 0.014, 95% CI = [0.223, 0.749], p < 0.001) (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

Discussion

The study had the following findings. First, ADHD patients in the CBT + M group outperformed the M-only group in the reduction of ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, a trend of reduction of maladaptive cognitions, and improvement of the psychological domain of QoL. Second, the changes in ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and psychological QoL correlated with each other. Besides, the influence of CBT on QoL was mediated through the following four pathways: 1) changes in ADHD core symptoms; 2) changes in depressive symptoms; 3) changes in depressive symptoms and then maladaptive cognitions; and 4) changes firstly in depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and then ADHD core symptoms.

Long-term effectiveness

First, we found that adults in the CBT + M group had a greater reduction in ADHD core symptoms when compared with the M-only group, consistent with previous studies compared with the treatment as usual at follow-up 12 weeks after the end of treatment [18, 21, 48] and relaxation training [16] and clinical management [49] at the 12-month follow-up. Our study further confirmed the effectiveness of CBT on medicated patients in the long-term follow-up. The superiority of CBT on ADHD core symptoms mainly results in regular and repeated practice of compensatory strategies, such as organization and planning skills in daily life, which could be accumulated and bring long-term benefits, consistent with our assumption in previous studies [22, 31]. One study [50] found the effectiveness of CBT on core symptoms might be masked if patients performed good responses to medication, as studies indicated the benefits of medication on ADHD core symptoms [51, 52]. Thus, a combination of CBT can be an effective supplementary treatment for core symptoms impairment in addition to stable medication.

Additionally, the CBT + M group showed a larger improvement in self-reported depression symptoms than the M-only group during the long-term follow-up, in line with the studies of Safren [16] but contrasted with the findings of Philipsen [49] and Corbisiero [50]. Similar to ADHD core symptoms, the emotional symptom reductions in the CBT + M group would be masked since medication also benefits patients’ emotional dysregulation and emotional symptoms related to ADHD [51, 53]. Previous studies also found equal effectiveness of CBT in depressive symptoms when combined with medication or not [32, 54, 55], leading to the hypothesis that CBT might be more effective in depressive symptoms.

This study indicated the effectiveness of CBT in reducing maladaptive cognitions in patients with ADHD, in line with those patients with depression [56], insomnia [57], and agoraphobia [58]. The ATQ was used to assess the frequency of negative automatic thoughts [40], and the DAS was developed to assess the beliefs or attitudes that underlie the characteristic cognitive content, especially with depression [41]. Patients with ADHD were found to have shown elevated scores of maladaptive cognitions, which correlated with emotional symptoms [59]. CBT helps ADHD patients improve their cognitive flexibility and reframe their maladaptive cognitions, and the long-term effectiveness would also be obtained through the benefits in the improvement of depressive symptoms.

Our study emphasized the effectiveness of CBT treatment on psychological QoL, in line with a previous RCT at the 3-month follow-up [19, 21, 48] with moderate to large effect sizes. The WHOQOL-psychological domain emphasizes an individual’s positive feelings, personal beliefs, and self-esteem [60], which could be improved by CBT from positive reinforcement, intimacy, interpersonal learning, social support [61], and self-efficacy accumulation supported by the therapist [62].

Correlations between changes in ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and psychological QoL

The results found positive relationships between the changes in depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and QoL, in line with studies on depression [56]. The positive relationship between core symptoms and QoL changes was in line with the RCT study of ADHD adults [19]. Besides, we found that the correlation between changes in ADHD core symptoms and QoL was strong in the M-only group but moderate in the CBT + M group, indicating that other factors would also be correlated with life quality change, such as emotional changes caused by CBT [63]. A previous study found that medicated adults with ADHD still have emotional distress and maladaptive cognitions [64], and CBT helps patients improve negative emotions and comorbid symptoms, which would be beneficial to better QoL improvement.

Mediation analyses

We first explored the effect of CBT on QoL in adults with ADHD in the long-term follow-up and found that the changes in ADHD core symptoms, depression, and maladaptive cognitions are all direct or indirect mediators of the influence of CBT on QoL.

First, the influence of CBT on QoL through ADHD core symptoms emphasized the importance of core symptom reduction in QoL improvement. Besides, the mediating role of ADHD core symptoms also exists through depressive symptoms and then maladaptive cognition changes. CBT helps ADHD patients develop problem-solving strategies and compensatory skills that target core symptoms, and the reduction of core symptom impairment would be beneficial to functional outcomes [7]. Besides, changes in negative emotions and then related maladaptive cognitions are also considered positive factors of core symptoms and QoL prognosis, since the compensatory strategies and skills learning could be better obtained with fewer depressive symptoms.

Second, we found that the changes in depressive symptoms fully mediated the relationship between CBT and QoL. The decrease in depression was related to increases in QoL [65], and changes in mental health-related QoL over the course of treatment were accounted for by changes in depression [63]. A similar mediating role has also been found in emotional distress related to insomnia [29] and physical diseases [66, 67]. Both group cohesion and CBT-related skills training can improve emotional symptoms [68,69,70]. Additionally, the accumulation of positive feedback and support from others and interpersonal learning in groups can bring long-term benefits, such as improvements in depressive symptoms, and then benefit QoL improvement when extended to daily life [71, 72]. The mediating role of maladaptive cognitions was also observed via the change in depressive symptoms. Dysfunctional attitudes are proposed to be a consequence of depressive symptom reduction [73, 74], and the reduction of depression would also improve the related dysfunctional attitudes and negative automatic thoughts, which could then bring a better QoL outcome.

Clinical and research implications

Our study explored the effectiveness of CBT in adults with ADHD in the long-term follow-up in multiple dimensions, and first explored the potential mechanism of CBT based on the CBT conceptual model in clinical samples. These findings indicate the possibility and necessity for clinicians to pay more attention to the residual symptoms of medicated ADHD, especially on their QoL, and the potential psychological mechanisms from the CBT perspective. Besides, our findings also highlight the important role in reducing emotional distress when working with ADHD due to the significant functional impacts via poor experiences accumulation and emotional distress [62]. Also, preventive interventions for emotional problems and functional impairments in the ADHD population are essential across the lifespan, which have already been explored preliminarily in adolescents [75] and would be further considered and implemented in adulthood in future studies.

Limitations of study

There were several limitations of our study. First, we focused on the effectiveness of CBT on QoL and their mediating factors including improvement of ADHD core symptoms, depression, and maladaptive cognitions, since participants involved in our study still struggled with emotional and QoL distress. The role of compensatory strategies and targeted, skills-based interventions and their relationship with maladaptive cognitions and emotions need to be explored in future studies. Second, an additional CBT-only group without medication could be included in future RCT studies to explore the role and mechanism of medication, CBT, and the combination of these treatments. Also, a broader range of participants with years of education and intellectual level is needed for future studies to identify the optimal combination, integration, and timing of known efficacious CBT interventions in different populations.

Conclusion

Our study further confirmed the long-term effectiveness of CBT on ADHD core symptoms, depressive symptoms, maladaptive cognitions, and psychological QoL in medicated adults with ADHD with residual symptoms. The CBT conceptual model in clinical samples was verified, indicating that the influence of CBT on QoL was mediated through changes in ADHD core symptoms, changes in depressive symptoms, and changes in depressive symptoms and then maladaptive cognitions. The mediating role of ADHD core symptoms also exists indirectly through the changes in emotional symptoms and then cognitive patterns. Our study provides a scientific basis for efficacious CBT interventions for ADHD patients, especially for those with residual symptoms. The potential mechanism was explored for a deeper understanding of how CBT works for a better QoL outcome.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data analysed during the current study will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity-Disorder

- ADHD-RS:

-

ADHD Rating Scale

- CBT:

-

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

- RCT:

-

Randomised Controlled Trial

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- MLM:

-

Mixed linear model

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

References

American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition. 2013.

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psycholog Med. 2006;36(2):159-65.

Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, Hechtman LT, Kennedy TM, Owens E, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:142–51.

Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros Á, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:204–11.

Goodman DW. The consequences of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:318–27.

Harpin VA. The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(SUPPL. 1):2–7.

Knouse LE, Safren SA. Current status of cognitive behavioral therapy for adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:497–509.

Bond DJ, Hadjipavlou G, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, et al. The Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ann Clin psychiatry Off J Am Acad Clin Psychiatr. 2012;24:23–37.

Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, Madhoo M, Kewley G. Long-term outcomes of ADHD: academic achievement and performance. J Atten Disord. 2020;24:73–85.

Edvinsson D, Ekselius L. Long-term tolerability and safety of pharmacological treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A 6-year prospective naturalistic study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;38:370–5.

Buitelaar JK, Trott G-E, Hofecker M, Waechter S, Berwaerts J, Dejonkheere J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety outcomes with OROS-MPH in adults with ADHD. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:1–13.

de Faria JCM, Duarte LJR, Ferreira LD, da Silveira VT, Menezes de Pádua C, Perini E. “Real-world” effectiveness of methylphenidate in improving the academic achievement of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosed students-A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47:6–23.

Safren SA, Sprich SE, Cooper-Vince C, Knouse LE, Lerner JA. Life impairments in adults with medication-treated ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2010;13

Parkin R, Nicholas FM, Hayden JC. A systematic review of interventions to enhance adherence and persistence with ADHD pharmacotherapy. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;152:201–18.

Kooij JJS, Bijlenga D, Salerno L, Jaeschke R, Bitter I, Balázs J, et al. Updated European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56

Safren SA, Sprich S, Mimiaga MJ, Surman C, Knouse L, Groves M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs relaxation with educational support for medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(8):875-80.

Solanto MV, Marks DJ, Wasserstein J, Mitchell K, Abikoff H, Alvir JMJ, et al. Efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy for adult ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167

Young S, Khondoker M, Emilsson B, Sigurdsson JF, Philipp-Wiegmann F, Baldursson G, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy in medication-treated adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and co-morbid psychopathology: A randomized controlled trial using multi-level analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45

Young S, Emilsson B, Sigurdsson JF, Khondoker M, Philipp-Wiegmann F, Baldursson G, et al. A randomized controlled trial reporting functional outcomes of cognitive–behavioural therapy in medication-treated adults with ADHD and comorbid psychopathology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;267

Safren SA, Sprich S, Chulvick S, Otto MW. Psychosocial treatments for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2004;27

Dittner AJ, Hodsoll J, Rimes KA, Russell AJ, Chalder T. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a proof of concept randomised controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137:125–37.

Pan M-R, Zhang S-Y, Qiu S-W, Liu L, Li H-M, Zhao M-J, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy in medicated adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in multiple dimensions: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;272:235–55.

Sadeghian Nadooshan MR, Shahrivar Z, Mahmoudi Gharaie J, Salehi L. ADHD in adults with major depressive or bipolar disorder: does it affect clinical features, comorbidity, quality of life, and global functioning? BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:707.

Matthies S, Sadohara-Bannwarth C, Lehnhart S, Schulte-Maeter J, Philipsen A. The impact of depressive symptoms and traumatic experiences on quality of life in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2018;22:486–96.

Zhang S-Y, Qiu S-W, Pan M-R, Zhao M-J, Zhao R-J, Liu L, et al. Adult ADHD, executive function, depressive/anxiety symptoms, and quality of life: A serial two-mediator model. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:97–108.

Windgassen S, Goldsmith K, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. Establishing how psychological therapies work: the importance of mediation analysis. J mental health (Abingdon, England). 2016;25:93–9.

Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:1–27.

A-Tjak JG, Morina N, Topper M, Emmelkamp PM. One year follow-up and mediation in cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for adult depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:41.

Espie CA, Emsley R, Kyle SD, Gordon C, Drake CL, Siriwardena AN, et al. Effect of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry. 2019;76:21–30.

Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, Katz LA, Gudleski GD, Blanchard EB. How does cognitive behavior therapy for irritable bowel syndrome work? A mediational analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterol. 2007;133:433–44.

Huang F, Tang YL, Zhao M, Wang Y, Pan M, Wang Y, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: A randomized clinical trial in China. J Atten Disord. 2019;23

Pan M-R, Huang F, Zhao M-J, Wang Y-F, Wang Y-F, Qian Q-J. A comparison of efficacy between cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and CBT combined with medication in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2019;279

Pan M-R, Zhao M-J, Liu L, Li H-M, Wang Y-F, Qian Q-J. Cognitive behavioural therapy in groups for medicated adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e037514.

Kollins SH, Sparrow EP. Guide to Assessment Scales in Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Kollins SH, Sparrow EP, Conners CK, editors. Tarporley: Springer Healthcare Ltd.; 2010.

Safren SA, Otto MW, Sprich S, Winett CL, Wilens TE, Biederman J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:831–42.

First MB, Gibbon M. The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) and the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II disorders (SCID-II). 2004.

Ryan JJ, Dai X, Paolo AM. Verbal-performance IQ discrepancies on the mainland Chinese version of the Wechsler adult intelligence scale (WAIS-RC). J Psychoeduc Assess. 1995;13:365–71.

DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale—IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. 1998;24(2):172-8.

Zung WWK, Richards CB, Short MJ. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic: further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:508–15.

Hollon SD, Kendall PC. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognit Ther Res. 1980;4:383–95.

Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and Validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A Preliminary Investigation. Report: ED167619. 33pp. Mar 1978. 1978.

Power M, Kuyken W. World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–85.

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial a report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310.

Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA. Best practices for missing data Management in Counseling Psychology. J Couns Psychol. 2010;57:1–10.

Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–36.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:424–53.

Emilsson B, Gudjonsson G, Sigurdsson JF, Baldursson G, Einarsson E, Olafsdottir H, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy in medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:116.

Philipsen A, Jans T, Graf E, Matthies S, Borel P, Colla M, et al. Effects of group psychotherapy, individual counseling, methylphenidate, and placebo in the treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1199-210.

Corbisiero S, Bitto H, Newark P, Abt-Mörstedt B, Elsässer M, Buchli-Kammermann J, et al. A Comparison of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Pharmacotherapy vs. Pharmacotherapy Alone in Adults With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9

Moukhtarian TR, Cooper RE, Vassos E, Moran P, Asherson P. Effects of stimulants and atomoxetine on emotional lability in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;44:198–207.

Jaeschke RR, Sujkowska E, Sowa-Kućma M. Methylphenidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a narrative review. Psychopharmacol. 2021;238:2667–91.

Snircova E, Marcincakova-Husarova V, Hrtanek I, Kulhan T, Ondrejka I, Nosalova G. Anxiety reduction on atomoxetine and methylphenidate medication in children with ADHD. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:476–81.

Cherkasova MV, French LR, Syer CA, Cousins L, Galina H, Ahmadi-Kashani Y, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy with and without medication for adults with ADHD: A randomized clinical trial. J Atten Disord. 2020;24

Weiss M, Murray C, Wasdell M, Greenfield B, Giles L, Hechtman L. A randomized controlled trial of CBT therapy for adults with ADHD with and without medication. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12

Cristea IA, Huibers MJH, David D, Hollon SD, Andersson G, Cuijpers P. The effects of cognitive behavior therapy for adult depression on dysfunctional thinking: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;42:62–71.

Thakral M, Von Korff M, McCurry SM, Morin CM, Vitiello MV. Changes in dysfunctional beliefs about sleep after cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;49:101230.

Bouchard S, Gauthier J, Nouwen A, Ivers H, Vallières A, Simard S, et al. Temporal relationship between dysfunctional beliefs, self-efficacy and panic apprehension in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38:275–92.

Torrente F, López P, Alvarez Prado D, Kichic R, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Lischinsky A, et al. Dysfunctional cognitions and their emotional, behavioral, and functional correlates in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): is the cognitive-behavioral model valid? J Atten Disord. 2014;18

WHOQOL-BREF. WHOQOL-BREF : introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment : field trial version, December. World health Organization. 1996;:1–16.

Joyce AS, Ogrodniczuk JS, Kealy D. Intensive evening outpatient treatment for patients with personality dysfunction: early group process, change in interpersonal distress, and longer-term social functioning. Psychiatry (New York). 2017;80:184–95.

Ramsay JR. CBT for adult ADHD: Adaptations and hypothesized mechanisms of change. J Cogn Psychother. 2010;24(1):37-45.

Kolovos S, Kleiboer A, Cuijpers P. Effect of psychotherapy for depression on quality of life: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:460–8.

Pan M-R, Zhang S-Y, Chen C-L, Qiu S-W, Liu L, Li H-M, et al. Bidirectional associations between maladaptive cognitions and emotional symptoms, and their mediating role on the quality of life in adults with ADHD: a mediation model. Front psychiatry. 2023;14:1200522.

Oei TP, McAlinden NM. Changes in quality of life following group CBT for anxiety and depression in a psychiatric outpatient clinic. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:1012–8.

Charalambous A, Giannakopoulou M, Bozas E, Paikousis L. Parallel and serial mediation analysis between pain, anxiety, depression, fatigue and nausea, vomiting and retching within a randomised controlled trial in patients with breast and prostate cancer. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026809.

Paulus DJ, Brandt CP, Lemaire C, Zvolensky MJ. Trajectory of change in anxiety sensitivity in relation to anxiety, depression, and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS following transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cogn Behav Ther. 2020;49:149–63.

Bramham J, Young S, Bickerdike A, Spain D, McCartan D, Xenitidis K. Evaluation of group cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2009;12:434–41.

Budman SH, Soldz S, Demby A, Feldstein M, Springer T, Davis MS. Cohesion, Alliance and outcome in group psychotherapy. Psychiatry (New York). 1989;52:339–50.

Norton PJ, Kazantzis N. Dynamic relationships of therapist alliance and group cohesion in transdiagnostic group CBT for anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:146–55.

Knouse LE, Zvorsky I, Safren SA. Depression in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): the mediating role of cognitive-behavioral factors. Cognit Ther Res. 2013;37:1220–32.

López-Pinar C, Martínez-Sanchís S, Carbonell-Vayá E, Fenollar-Cortés J, Sánchez-Meca J. Long-term efficacy of psychosocial treatments for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Front Psychol. 2018;9:638.

Quilty LC, McBride C, Bagby RM. Evidence for the cognitive mediational model of cognitive behavioural therapy for depression. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1531–41.

Quigley L, Dozois DJA, Bagby RM, Lobo DSS, Ravindran L, Quilty LC. Cognitive change in cognitive-behavioural therapy v. pharmacotherapy for adult depression: a longitudinal mediation analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49:2626–34.

Vitiello B, Davico C, Döpfner M. Is prevention of ADHD and comorbid conditions in adolescents possible? J Atten Disord. 2024;28:225–35.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the subjects for participation in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (CFH: 2024–2-4114) & Key Attending Psychiatrist Program of Peking University Sixth Hospital (BDLYYLZL2023–03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mei-Rong Pan (ORCID: 0009–0008–0883-3118): investigation, methodology, literature search, figures, data analysis, data interpretation, writing - original draft. Min Dong: investigation, data analysis. Shi-Yu Zhang: investigation, data collection, validation, visualization. Lu Liu (ORCID: 0000–0003–0194-1454): resources, methodology, project administration. Hai-Mei Li: data curation, data collection. Yu-Feng Wang: conceptualization, resources, project administration. Qiu-Jin Qian (ORCID: 0000–0001–5060-3772): conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, project administration, writing - review & editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This trial has been approved by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committees of Peking University Sixth Hospital [(2018) Ethics review number (41)] and has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). We obtained informed consent from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, MR., Dong, M., Zhang, SY. et al. One-year follow-up of the effectiveness and mediators of cognitive behavioural therapy among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: secondary outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 24, 207 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05673-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05673-8