Abstract

Objective

Pregnant women experience enormous psychological pressure, particularly during the late trimester. Symptoms of depression in late pregnancy may persist postpartum, increasing the incidence of postpartum depression. This study is aimed to investigate the factors influencing depressive symptoms among pregnant women in their third trimester at a Chinese tertiary hospital and provide information for effective intervention.

Methods

Pregnant women in their third trimester who visited the Ningbo Women and Children’s Hospital between January 1, 2020 and June 30, 2022 participated in this study. A score of ≥ 13 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was considered as positive for depressive symptom. Potential influencing factors were examined by using an online questionnaire and analyzed using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

A total of 1196 participants were recruited. The mean EPDS score was 7.12 ± 4.22. The positive screening rate for depressive symptom was 9.9%. Univariate analysis showed that living with partner, annual family income, planned pregnancy, sleep quality, and partner’s drinking habits were related to positive screening for depression(P < 0.05). Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that living away from the partner (odds ratio [OR]: 2.054, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.094–3.696, P = 0.02), annual family income < 150,000 Chinese Yuan (CNY; OR: 1.762, 95% CI: 1.170–2.678, P = 0.007), poor sleep quality (OR: 4.123, 95% CI: 2.764–6.163, P < 0.001), and partner’s frequent drinking habit (OR: 2.227, 95% CI: 1.129–4.323, P = 0.019) were independent influencing factors for positive depression screening (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Family’s economic condition, sleep quality, living with partner, and partner's drinking habits were related to positive depression screening in late pregnancy. Pregnant women with these risk factors should be given more attention and supported to avoid developing depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pregnancy is a period of significant change in a woman's physiology and psychology [1]. During pregnancy, women are vulnerable to the negative impacts of life events that may cause depressive symptoms. The prevalence of prenatal depressive symptoms is approximately 14%-23%, and is a major global public health concern [2,3,4]. Prenatal depression may reduce self-care ability, cause an increase in maternal and infant incidences such as poor pregnancy outcomes [4], higher postpartum depression, and negative impacts on fetal and child health [2, 5]. The third trimester is the link between preconception and postnatal needs and is an important node for women to become mothers. A recent study found that depression inlate pregnancy and postpartum period was strongly correlated (r = 0.706, P < 0.001) [6]. In the third trimester, pregnant women experience more physical changes, greater psychological burden, and an increased probability of pregnancy complications, which increase the risk of depressive symptoms.

There are several studies about the influencing factors for depressive symptoms in western countries [7,8,9,10,11]. It is reported that factors related to depressive symptoms in pregnant women included history of depression, negative obstetric experiences, lack of social support, low education, and alcohol consumption and smoking. However the results between these factors and pregnancy-induced depression are not completely consistent. For socio-demographic factors such as age, for example, some studies found an association with younger maternal age [12], some studies have found they opposite [13, 14], while some studies have also found that there is no significant correlation between age and depressive symptoms [15, 16]. In terms of educational attainment, many studies have found that pregnant women with lower levels of education are more likely to suffer from depression during pregnancy [17,18,19,20]. Another studie [21] showed that the longer the number of years of schooling, the higher the risk of depression, while some studies reported no associations between years of schooling and depression [16, 22, 23]. Pregnancy characteristics such as planned pregnancy [7], history of abortion [8] and Psychosocial factors such as socioeconomic status, studies have found that socioeconomic factors are closely associated with the risk of depressive symptoms in pregnant women [24, 25]. However, some previous studies did not observe this association [26, 27]. Different regions have different influencing factors. So far, depressive symptoms were rarely reported in China. Ningbo is a port city with a highly mobile population, with migrant pregnant women from all over the country accounting for nearly half of all pregnant women, while none studies focused on depression in pregnancy up to now. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the factors influencing depressive symptoms among pregnant women in late pregnancy and to provide evidence for effective intervention.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ningbo Women and Children's Hospital (EC2022-045) and included in the cohort study of “Study for the epidemiology of perinatal depression in China”, which was registered in Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR1900027020). Pregnant women in the third trimester (28–42 gestational weeks) who visited Ningbo Women and Children's Hospital from January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2022, were recruited as the participants. Informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Inclusion criteria included: pregnant women in late pregnancy lived for more than 6 months in Ningbo City and had signed informed consent (gestational week: 28 weeks and beyond).

Exclusion criteria included: (1)patients with mental or psychological disorders before pregnancy; (2)patients with hypertension, diabetes, malignancies, chronic anemia, heart diseases, liver diseases, and kidney diseases before pregnancy;(3) those who were unable to complete the questionnaire due to communication impairment or reading disorders.

Sample size

The required sample size was calculated using the formula:

Where, \(\mathrm{\alpha }=0.05\), \({\mathrm{z}}_{1-\alpha /2}=1.96\), \(p=50\mathrm{\%}\)(as the positive depression screening rate was unknown, p was set at 50% to estimate the largest sample size), allowable error \(\updelta =0.03\). The sample size was calculated as 1067 at 95% confidence limit. With a 15% of non-response rate, \(\mathrm{N}=1067\div \left(1-15\%\right)=1255\).

Depressive symptom assessment

Following the “Expert Consensus on Maternal Mental Health Management (2019)” [28], we used the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assess depression. Chinese version of the EPDS, which has been tested in Hong Kong [29] and Beijing [30] and has showen good reliability and effectiveness. The scale can be completed in approximately 5 min and the total score is calculated by adding item scores. Responses to the questions are scored from 0–3 based on the problem severity; question numbers 3 and 5–10 are reverse scored. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. Babu Ram et alrevealed that a cutoff score of 13 yields a sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 95.6% among Asian women, respectively [31]. Therefore, cut-off score of a total score ≥ 13 points or one score ≥ 1 for item 10 was considered as positive depression screening in this study.Those with positive results were advised to undergo a comprehensive clinical interview for further evaluation, and appropriate treatment was provided. Non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies were used for the patients.

Exposure variables

Exposure variables were measured using an online questionnaire. Participants responded tothe online questionnaire after understanding the quick response (QR) codes and signed an informed consent.

The exposure variables were: (1) basic parameters, (2) pregnancy and delivery information, (3) lifestyle, (4) partnerinformation (Table 1).

Body mass index (BMI) “before pregnancy” was defined as the value for the “latest 3 months before pregnancy.” Annual family income was defined as the total income of the participant and her partner in the past year, including salary, financial products, and rental income, etc.Sports (Yes) impliedexercising except for walking three times per week and 30 min per session. Drinking conditions were categorized into never, occasionally, and frequently; drinking once weekly was defined as frequent drinking. The smoking status was categorized into ≥ 100 cigarettes during the whole pregnant period, < 100 cigarettes during the whole pregnant period, and never by far. Living separatey from the partner for more than 3 months per year was defined as living away from the partner.

Specially trained nurses helpedthe participants understand the questionnaire content accurately.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to process the data. The counting data were expressed in frequency (percentage). Differences between groups were compared with χ2 inspection, and variables with P < 0.05 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

General information

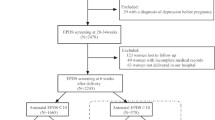

In this study, 1278 participants responded to the questionnaire, and 1196 (93.58%) provided valid response (Fig. 1). The remaining were excluded due to incompleteness of responses and withdrawal of participation. The participants' average ages were 29.57 years(SD: 4.35), average gestational weeks were 37.16(SD:2.89), and local residents comprised 40.65%(486/1196). Primiparas accounted for 62.96% (753/1196) and the restwere multiparas. Singleton and twin pregnancy comprised 95.07% (1137/1196) and 4.93% (59/1196), respectively. Among the participants, 119 (9.9%) were screened positive for depressive symptoms. The mean EPDS score was 7.12 (SD:4.22).

Univariate analysis

Annual family income, planned pregnancy, sleep quality, living away from partner, and partner's drinking habit were significantly affected depression screening (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

Table 2 and Fig. 2 showed that living away from partner(odds ratio [OR]: 2.054, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.094–3.696, P = 0.02), annual family income < 150,000CNY(OR: 1.762, 95% CI: 1.170–2.678, P = 0.007), poor sleep quality(OR: 4.123, 95% CI: 2.764–6.163, P < 0.001), and partner’s frequent drinking habit (OR: 2.227, 95% CI: 1.129–4.323, P = 0.019) were independent influencing factors of screening positive for depression (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, 1196 (93.58%) valid questionnaires were obtained. The mean EPDS score was 7.12, and 9.9% of the participants were screened positive for depressive symptoms. Living away from partner, low annual family income, poor sleep quality, and partner’s frequent drinking habit were independent influencing factors of late pregnancy depressive symptoms. In this study, the mean EPDS score was 7.12 (SD:4.22), which was higher than some European countries such as Spain 5.73 [32], Hungary 5.36 [33], Sweden 5.75 [34]. China is a developing country with lower household incomes, lower levels of health care than Europe countries, and a lack of attention to mental health care, which can lead to high scores. This difference in scores needs to be confirmed by high-quality systematic reviews and another Subscale analysis of EPDS (anhedonia, depression anxiety) can also be used in future [35].

Studies from various countries showed a prevalence rate of screened positive for depressive symptoms was 8.1%–46.8% [36,37,38]. In our study, the rate (9.9%) was lower than that in other developing countries such as India (35.7%) [39], Thailand (46.8%) [38], Nepal (18.2%) [40] and Ethiopia (15.5%) [41]. Certain cultures may be responsible for different screening rates. Influenced by the traditional culture, pregnant women in China are inclined to hide their negative emotions. To maintain their personal and family image, they prefer to show their "positive" side to outsiders, while hiding the "negative" and "repressed" emotions inside. This Stoic character may have biased the screening score, resulting in a lower positive screening rate than that in other countries. However, this "suppressed" character can increase the possibility of unnoticed depressive symptoms and should be paid more attention.

Studies have found that socioeconomic factors are closely associated with the risk of depressive symptoms in pregnant women [24, 25, 30]. This is consistent with the findings of our study. However, some previous studies did not observe this association [26, 27]. This may be related to different economic conditions. A study in China showed a lower depressive symptom rate in pregnant women with an annual family income of more than 200,000 CNY compared to those with an income of less than 100,000 CNY [30]. A study in a southern state of India, which set the cut-off to 50,000 Indian Rupee(INR) and 1lakh INR did not find an association [27]. Concerning the economic level of Ningbo, we set a cutoff of 150,000 CNY (the average annual income of Ningbo households in the last 2 years). Our research showed a 1.762 time higher risk of depressive symptoms in pregnant women with an annual family income < 150,000 CNY than in those with ≥ 150,000 CNY. Pregnant women with low family incomes face more economic pressure during pregnancy and while raising babies. In the third trimester, pregnant women are more likely to have depressive symptoms for economic reasons as they face problems such as the imminent birth of their child and post-birth support. Family members should provide them with greater economic security. Additionally, the society and the government need to optimize policies to support them.

Previous studies have suggested that perinatal depressive symptoms are associated with poor sleep quality. A meta-analysis found that women who experienced poor sleep during pregnancy had a significantly higher risk of developing depressive symptoms(OR:3.72) [42]. For women in late pregnancy, due to frequent urination, fetal movement, leg cramps, and bad sleeping posture, sleep time is shortened, which may reduce sleep quality [43,44,45]. Although different methods are used to assess sleep quality, studies have shown that sleep quality is associated with depressive symptoms during late pregnancy [43, 46,47,48]. In our study, the risk of depressive symptoms in pregnant women with poor sleep quality was higher than that in those with good sleep quality (OR: 4.123, 95% CI: 2.764–6.163), which is consistent with previous studies. More attention should be given to sleep quality of pregnant women and appropriate guidance should be provided to those with poor sleep quality.

Ningbo is an open coastal city with a large fluid population. As many couples live separately, it is important to survey the influence of living separately ondepression among pregnant women. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first survey on this aspect. Our results showed that when couples did not live together, the risk of late pregnancy depression increased 2.054 times. The relationship between pregnant women and their partners is important for their emotional health [49, 50]. In recent years, under the influence of Western culture, the young Chinese population have abandoned the concept of a large family (living with their parents) and have become accustomed to living as couples. During pregnancy, especially in the late trimester, separation with partner may cause insecurity in pregnant women, increase their fear of childbirth, and cause depressive symptoms. We advocate that partnersprovide company to pregnant women during the perinatal period.

Alcohol consumption must be avoided during pregnancy. Fortunately, in this study, the drinking rate decreased from 38.71% before pregnancy to 1.34% during pregnancy, which is lower than that found by Amna [51]. However, we found that frequent drinking of partner increased the risk of late pregnancy depressive symptoms by 2.227 times. Partners’ alcohol consumption may cause tension and violence in relationships. Intimate partner violence is significantly associated with antenatal depressive symptoms [52, 53]. During the third trimester, the body size of pregnant women increases and they become less mobile. When faced with partner's drinking, the tension in the relationship is more likely to produce insecurity and depressive symptoms.

There are several limitations to this study. The major limitation of the study is that the findings are subject to reverse causation. For example it is possible that mothers experiencing prenatal depression are more likely to develop sleep disturbance. In the same way, fathers with depressed mothers may present with increased alcohol consumption than counterparts with non-depressed mothers. First of all, our hospital is the critical maternal rescue center in Ningbo, although our hospital only accounts for one-fifth of the city's births, the proportion of high-risk women is relatively large. That may biased the final results. Second, in this study, the dynamic psychological changes after delivery and the mental status of her babies were not analyzed, therefore a long-term prospective multi-center study is warranted. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

This study found that the positive screening rate for depressive symptoms in late pregnancy was 9.9% at a tertiary hospital. Living away from partner, low annual family income, poor sleep quality, and partner’s frequent drinking habit were independent influencing factors for late pregnancy depressive symptoms. This study provides aninformation of higher depressive symptoms in pregnant women in the third trimester, which calls for a joint effort by society, healthcare professionals, families, and pregnant women. Since 2021, the Chinese Medical Association (CMA) has recommended the inclusion of depression screening for pregnant women into prenatal care. If the mother's score is considered positive, the obstetrician will recommend that they undergo a comprehensive clinical interview for further evaluation and appropriate treatment. Non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies were used for the patients. And there were no information about mental health in prenatal classes for couples before 2022 in our prenatal care clinic. This year, we are offering this courses on mental health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Psychosomatic Health Society CPMA, Committee of Women Mental Health Care CMaCHA. Consensus on maternal mental health management (2019). Chin J Woman Child Health Res. 2019;30(07):781–6.

Priya A, Chaturvedi S, Bhasin SK, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among pregnant women: a community-based study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(1):151–2.

Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, et al. Depression during pregnancy : overview of clinical factors. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24(3):157–79.

Miller ES, Saade GR, Simhan HN, et al. Trajectories of antenatal depression and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(1):108 e1–108 e9.

Ma X, Wang Y, Hu H, et al. The impact of resilience on prenatal anxiety and depression among pregnant women in Shanghai. J Affect Disord. 2019;1(250):57–64.

Yang YH, Huang X, Sun MY, et al. Analysis on depression state outcomes and influencing factors of persistent depression in pregnant and perinatal women in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2022;43(1):58–64.

Mohammad KI, Gamble J, Creedy DK. Prevalence and factors associated with the development of antenatal and postnatal depression among Jordanian women. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):e238–45.

Scheidt CE, Kunze M, Wangler J, et al. Psychological consequences of perinatal loss in subsequent pregnancies–a comparative study. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2008;58(12):475–8.

Tong VT, Farr SL, Bombard J, et al. Smoking before and during pregnancy among women reporting depression or anxiety. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):562–70.

Tefera TB, Erena AN, Kuti KA, et al. Perinatal depression and associated factors among reproductive aged group women at Goba and Robe Town of Bale Zone, Oromia Region, South East Ethiopia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2015;1:12.

Redshaw M, Henderson J. From antenatal to postnatal depression: associated factors and mitigating influences. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(6):518–25.

Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, et al. Depressed mood in pregnancy: prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reprod Health. 2011;2(8):9.

Raisanen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, et al. Risk factors for and perinatal outcomes of major depression during pregnancy: a population-based analysis during 2002–2010 in Finland. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e004883.

Weobong B, Soremekun S, Ten Asbroek AH, et al. Prevalence and determinants of antenatal depression among pregnant women in a predominantly rural population in Ghana: the DON population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:1–7.

Fellenzer JL, Cibula DA. Intendedness of pregnancy and other predictive factors for symptoms of prenatal depression in a population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2426–36.

Martini J, Petzoldt J, Einsle F, et al. Risk factors and course patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders during pregnancy and after delivery: a prospective-longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;1(175):385–95.

Zhang Y, Muyiduli X, Wang S, et al. Prevalence and relevant factors of anxiety and depression among pregnant women in a cohort study from south-east China. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2018;36(5):519–29.

Dmitrovic BK, Dugalic MG, Balkoski GN, et al. Frequency of perinatal depression in Serbia and associated risk factors. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60(6):528–32.

Abuidhail J, Abujilban S. Characteristics of Jordanian depressed pregnant women: a comparison study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(7):573–9.

Niazi AU, Alekozay M, Osmani K, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among pregnant women in Herat, Afghanistan: a cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(8):e1490.

Karmaliani R, Asad N, Bann CM, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and associated factors among pregnant women of Hyderabad. Pakistan Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2009;55(5):414–24.

Ratcliff BG, Sharapova A, Suardi F, et al. Factors associated with antenatal depression and obstetric complications in immigrant women in Geneva. Midwifery. 2015;31(9):871–8.

Agostini F, Neri E, Salvatori P, et al. Antenatal depressive symptoms associated with specific life events and sources of social support among Italian women. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(5):1131–41.

Mersha AG, Abebe SA, Sori LM, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of perinatal depression in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2018;19(2018):1813834.

Zeng Y, Cui Y, Li J. Prevalence and predictors of antenatal depressive symptoms among Chinese women in their third trimester: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;2(15):66.

Abujilban SK, Abuidhail J, Al-Modallal H, et al. Predictors of antenatal depression among Jordanian pregnant women in their third trimester. Health Care Women Int. 2014;35(2):200–15.

Srinivasan N, Murthy S, Singh AK, et al. Assessment of burden of depression during pregnancy among pregnant women residing in rural setting of chennai. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2015;9(4):LC08–12.

Obstetric Subgroup SoO, Gynecology CMA. Experts consensus on screening and diagnosis of perinatal depression. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2021;56(8):521–7.

Lee DT, Yip SK, Chiu HF, et al. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:433–7.

Wu SS. Analysis of Depressive Symptoms and Influencing Factors During Pregnancy: Chinese Academy of Medical Science & Peking Union Medical College; 2020.

Bhusal BR, Bhandari N, Chapagai M, et al. Validating the edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in Kathmandu. Nepal Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10:71.

Vazquez MB, Miguez MC. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for depression in Spanish pregnant women. J Affect Disord. 2019;1(246):515–21.

Toreki A, Ando B, Dudas RB, et al. Validation of the edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in a clinical sample in Hungary. Midwifery. 2014;30(8):911–8.

Rubertsson C, Borjesson K, Berglund A, et al. The Swedish validation of Edinburgh postnatal depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(6):414–8.

Tuohy A, McVey C. Subscales measuring symptoms of non-specific depression, anhedonia, and anxiety in the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Clin Psychol. 2008;47(Pt 2):153–69.

Jigeer G, Tao W, Zhu Q, et al. Association of residential noise exposure with maternal anxiety and depression in late pregnancy. Environ Int. 2022;17(168):107473.

Cankorur VS, Abas M, Berksun O, et al. Social support and the incidence and persistence of depression between antenatal and postnatal examinations in Turkey: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006456.

Phoosuwan N, Eriksson L, Lundberg PC. Antenatal depressive symptoms during late pregnancy among women in a north-eastern province of Thailand: Prevalence and associated factors. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;36:102–7.

Sheeba B, Nath A, Metgud CS, et al. Prenatal depression and its associated risk factors among pregnant women in bangalore: a hospital based prevalence study. Front Public Health. 2019;3(7):108.

Joshi D, Shrestha S, Shrestha N. Understanding the antepartum depressive symptoms and its risk factors among the pregnant women visiting public health facilities of Nepal. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0214992.

Bisetegn TA, Mihretie G, Muche T. Prevalence and predictors of depression among pregnant women in Debretabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0161108.

Fu T, Wang C, Yan J, et al. Relationship between antenatal sleep quality and depression in perinatal women: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. J Affect Disord. 2023;14(327):38–45.

Mindell JA, Cook RA, Nikolovski J. Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances across pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2015;16(4):483–8.

Hashmi AM, Bhatia SK, Bhatia SK, et al. Insomnia during pregnancy: Diagnosis and Rational Interventions. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(4):1030–7.

Yu Y, Zhu X, Xu H, et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms and its influencing factors among pregnant women in late pregnancy in urban areas of Hengyang City, Hunan Province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e038511.

Polo-Kantola P, Aukia L, Karlsson H, et al. Sleep quality during pregnancy: associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(2):198–206.

Yu Y, Li M, Pu L, et al. Sleep was associated with depression and anxiety status during pregnancy: a prospective longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(5):695–701.

Zhang X, Cao D, Sun J, et al. Sleep heterogeneity in the third trimester of pregnancy: correlations with depression, memory impairment, and fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 2021;303:114075.

Noonan M, Jomeen J, Doody O. A review of the involvement of partners and family members in psychosocial interventions for supporting women at risk of or experiencing perinatal depression and anxiety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5396.

Antoniou E, Tzanoulinou MD, Stamoulou P, et al. The important role of partner support in women’s mental disorders during the perinatal period. A Lit Rev Maedica (Bucur). 2022;17(1):194–200.

Umer A, Lilly C, Hamilton C, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use in late pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2020;88(2):312–9.

Beyene GM, Azale T, Gelaye KA, et al. Depression remains a neglected public health problem among pregnant women in Northwest Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):132.

Ghoneim HM, Elprince M, Ali TYM, et al. Violence and depression among pregnant women in Egypt. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):502.

Acknowledgements

We thank those who have devoted much to this study, including nurses, study doctors, statisticians, reviewers, and editors, especially Dr.Xiaobo He. They were not financially compensated for their contributions.

Funding

This research is supported by Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province China (No. 2022KY1166).This study was Funded by Women's Health Care of Ningbo Key Medical Support Discipline (2022-F27) and the project of NINGBO Leading Medical & Health Discipline (Project number: 2010-S04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS: Data Collection, Manuscript Writing; XBH: Data Collection, XJG: Data Analysis; XPY: Project Development, Manuscript Editing. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The informed consent form and study protocol were approved by the Ethnic Committee of the Ningbo Women and Children’s Hospital (Approval No: EC2022-045). The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and Chinese law. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Cmpeting interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., He, X., Gu, X. et al. Risk factors of positive depression screening during the third trimester of pregnancy in a Chinese tertiary hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 824 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05343-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05343-1