Abstract

Background

There has been a noticeable relative increase in psychiatric comorbidities among smokers as opposed to the general population. This is likely due to comparatively slower decrease in smoking prevalence among individuals with mental health conditions. This study aims to assess the prevalence trend of past or current mental health disorders in individuals seeking specialized smoking cessation assistance.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective single-centre observational study to assess the presence of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, bipolar affective disorder, or schizophrenia in personal history of 6,546 smokers who sought treatment at the Centre for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence in Prague, Czech Republic between 2006 and 2019. The study examined the impact of gender, age, and the effect of successive years on the prevalence of the mental disorders using Poisson distribution regression.

Results

In the studied cohort, 1,743 patients (26.6%) reported having one or more mental disorders. Compared to patients without a psychiatric disorder, they exhibited similar levels of carbon monoxide in expired air (mean 17 ppm, SD 11 ppm) and scored one point higher on the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence. Among smokers with a mental disorder, women were more prevalent (62%) than men (38%). The prevalence of mental disorders increased on average by 4% every year, rising from 23% in 2006 to 35% in 2019.

Conclusions

Consistent with the observation that the prevalence of smoking among people with any mental disorder is higher and declining at a slower rate than in the general population, there is a steadily increasing percentage of these patients seeking specialized treatment over time. Professionals who offer tobacco dependence treatment should be aware of the upward trend in psychiatric disorders among smokers, as more intensive treatment may be needed. Similarly, psychiatric care should pay attention to smoking of their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

People with mental disorder smoke more often and more intensively compared to general population [1]. In the USA, it was reported that about 40% of cigarettes were sold to people with a mental disorder in 1990, while the smoking prevalence was 28% [2,3,4]. Similarly, more than half of all cigarettes sold in Australia, New Zealand, and the US in 2016 were sold to people with a mental disorder [4, 5]. In 2019, the prevalence of smokers reporting past-month cigarette use with any past-year mental disorder was 1.8 times higher than those without a mental disorder in the USA. There was 1.8 times higher prevalence of smokers reporting past-month cigarette with any past-year mental disorder than those without mental disorder reported in the USA in 2019 [6, 7]. Presumably, more than 60% of people with schizophrenia and as many as 33–70% of people with bipolar disorder smoke tobacco [8, 9].

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in people with schizophrenia [10]. Overall, tobacco-related diseases are the most frequent cause of death of persons with mental disorder, accounting for approximately 50% of deaths among people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression [11, 12].

Smoking cessation is generally associated with improved mental health [13]. There are indications that more difficult access to a treatment of tobacco dependence may contribute to the reported slower decline in smoking prevalence over time in people with mental disorders [1, 14]. The EAGLES study provides evidence that standard pharmacological and behavioural treatments, with modest adaptations, can be used safely and effectively in persons with a mental disorder [15]. It is therefore important that effective smoking cessation strategies are used to help people with severe mental disorders to stop smoking [1].

In the general Czech population, almost 30% have some mental disorder [16]. In the Czech Act on Protection of Health against the Harmful Effects of Addictive Substances prohibits smoking in public indoor spaces; however there is an exception that allows for a structurally separated area reserved for smoking in a closed psychiatric ward or other addiction treatment facility [17].

To date, little is known about the proportion of patients with a mental disorder among smokers seeking intensive treatment for tobacco dependence. This study aimed to address the research question regarding the temporal trend in prevalence of patients with a mental disorder among smokers seeking specialized tobacco dependence treatment.

Methods

The single-centre retrospective observational study was conducted at the Centre for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence of the 3rd Medical Department at the General University Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic (Centre). The publication of results of our standard treatment of tobacco dependence was approved by the Ethics Committee of General University Hospital in Prague No. 30/13, 49/21, and 1254/22 IS, D. At baseline visit, all patients signed informed consent and agreed to the evaluation of their personal data in anonymised form for research purposes.

The study site

The Prague-based Centre provides an intensive specialized tobacco dependence treatment to, roughly, 400–500 patients each year and operates full time for smokers since 2005. Patients could have been referred to the treatment Centre by their physician or self-refer. The treatment is based on evidence-based guidelines and has typically been tailored to the individual patient’s needs [18,19,20]. The treatment is provided by a nurse and a physician both with completed professional medical training, and it consists of face-to-face counselling – psychobehavioural intervention and mostly recommended pharmacotherapy including nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, cytisine, and/or bupropion. In frame of the personal history collection, patients were asked about mental disorders, and positive answers were sorted in the following categories: anxiety, depression, bipolar affective disorder, or schizophrenia. The diagnoses were not verified by psychiatrist. The initial psychobehavioural intervention lasted about 2 h and subsequent visits about 30 min, with 12-months follow-up as described elsewhere [21].

The treatment cohort and the data collection

The analysed dataset included 7,498 patients treated as outpatients from 2005 to 2021 during the 12-month follow-up period, with an average number of visits being 4.3 (SD 2.7). The participants had an average age of 44.0 years (SD 14.0 years), with 52% male and 48% female. All individuals were aged 18 or older, heavily dependent on smoking, with an average of 21.7 cigarettes/day (SD 11.3 cigarettes/day) and average score of 5.5 points (SD 2.4 points) in the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) [22, 23].

For the sake of consistency, records from the years 2005, 2020 and 2021 were excluded. Additionally, individuals with missing key information during the overall period were excluded. Thus, for this analysis, we included only those with the date of the first visit falling before the start of COVID-19 epidemic (2006–2019), resulting in a sample size of N = 6,546.

The baseline visit lasted approximately 1 h and involved a basic medical examination along with data collection on demographics, smoking, smoking dependence characteristics, personal smoking and medical history, and self-reported psychiatric problems, current or past, such as anxiety, depression, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, including the year of onset and psychiatric pharmacological treatment. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) was also administered during the baseline visit [24, 25].

The statistical analysis

The data was described by means of the descriptive statistics in the software R v. 4.1.1 for Windows. Age groups were created as below 26, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, and above 65. Trend in the prevalence of reported mental disorders was analysed using the multivariate Poisson regression analyses of the R v. 4.2.1 for Windows package.

The year of the initial visit of the smoker in the Centre was taken as either metric covariate or a factor to better illustrate the year-to-year trend. In the either case, point and interval estimates of rate ratios associated with potential covariates were calculated and plotted as based on the multivariate generalized linear model with log-link function and Poisson distribution [26]. To obtain counts (N) by each factor combination, the records were grouped by the aforementioned age groups, gender, and the year of the first visit.

The general multivariate Poisson regression model with age as a covariate and gender as additional analysed factor was constructed as follows:

where the i denotes the gender and the year is studied as a continuous covariate. Alternatively, to understand the effect of individual years, the model was also fitted as:

where the i denotes the gender and the j the respective year studied as a factor. Both regression models estimate the prevalence rate ratio (PRR), the associated 95% confidence interval (CI), and the p-value as presented in Table 2.

Results

Cohort description

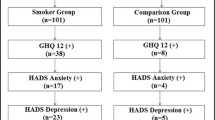

The full dataset of 7,498 individuals, collected from January 2005 through 31 December 2021 was cleaned for consistency and completeness, resulting in an analysis set of patients who attended an initial visit during the period from 2006 to 2019. Among the total of 6,546 patients, 1,743 (26.6%) reported one or more of the above-mentioned mental disorders—19,6% of men (668/3,400) and 34.2% of women (1,075/3,146). The details of the study cohort are presented in the Table 1. The total number of patients attending the initial visit was 500 or more each year during 2006–2009 with a downward trend in the following years except for 2017. The proportion of women attending their initial visit oscillated between 43 and 52% each year. Among patients with a mental disorder, women were more prevalent (62%) than men (38%). The average age of smokers at the baseline visit was 44 years (SD 14), both for smokers with and without a mental disorder. Similarly, there was no difference in the average number of cigarettes smoked per day – both groups reported an average of 22 cigarettes per day (SD 11). Additionally, the baseline CO levels of 17 ppm (SD 12) did not differ between both groups. However, the median FTCD score was significantly higher in those with a reported mental disorder (6 vs. 5 with IQR 4 vs. 3, respectively).

Data grouping

The 6,546 records grouped by age group, gender, and the year of first visit resulted in a contingency table of 168 groups with, on average, 39 (ranging from 2 to 119) records per group. The total number of patients (\({N}_{total}\)), the number of patients with mental disorder (\({N}_{mental\_disorder}\)), and the proportion of mentally ill patients were then calculated for each group to populate the regression model.

Regression analysis

As estimated by the model with the year as a continuous covariate (Eq. 1, Table 2), there is a rather consistent 4% annual increase (CI 3% to 5%) in prevalence of individuals with a mental disorder among those seeking help in the Centre. The plot based on the model with year as a factor (Eq. 2, Table 3, and Fig. 1) shows that after an initially oscillating trend between year 2006 and 2011, the prevalence rumps up, and five of the eight years following 2011 show significantly higher prevalence of individuals with mental disorder. In 2019, the prevalence of smokers with a mental disorder in the Centre was 52% higher than in 2006 (increased from 23 to 35%). The proportion of female individuals with a mental disorder was significantly higher than the proportion of male individuals with a mental disorder (p < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 2.

There is no obvious consistent trend between age and the prevalence of those with mental disorder. However, it seems that the prevalence of mental disorders is, roughly, high among those aged 36 to 65, followed by a drop in those 66 of age and older. This observation is however only speculative and is not supported by statistical inference.

Discussion

We found that the prevalence of smokers with a mental disorder who sought treatment was increasing year by year since 2011. Although there is predominance of males who smoke in the general population and among patients with mental disorders [27], our analysis showed a preponderance of females with mental disorders. Patients with and without a mental disorder did not differ in average age, CO level and number of cigarettes per day. The only significant difference was observed in the median FTCD score, which was higher in those who reported a mental disorder. This is in line with the findings of other studies, where the level of tobacco dependence tends to be more intense in people with a psychiatric disorder [28]. Psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, bipolar disorder, insomnia, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide attempts, and schizophrenia are common among smokers. Furthermore, recent studies have indicated that these disorders, aside from psychosocial aspects, may have genetic relationships [29]. Treatment outcomes in these patients tend to be worse compared to general population, especially for depression, where its presence at the start of treatment may predict reduced smoking abstinence after one year. However, a considerable improvement in depression was found in patients who successfully quit smoking and maintained one year of abstinence [30, 31].

It was reported that smoking prevalence in the Czech population aged 15 and older and including both daily and occasional smokers decreased from 31% in 2004 [32] to 24% in 2021 [33]. This trend can be understood as the result of a selective two-speed process where the general population increasingly abstains from smoking, but this occurs more slowly or not at all in those with a mental disorder. This is then reflected in a change in the relative representation of this group in the total smoker population over time. This trend is in accordance with the process in other countries, where the quicker decline in smoking prevalence was sooner reported in general population comparing to people with psychiatric comorbidity [34]. However, the England 2020 report already shows a significant decrease also in smokers with mental disorders [35]. Our herein presented data however show very high prevalence of mental disorders among smokers anyway. Although there is a well acknowledged trend to abandon smoking in the general population, the success rates in smoking cessation among those with a mental disorder remains unsatisfactory.

This study has several strengths. First of all, this is one of the largest cohorts of smokers undergoing tobacco dependence treatment with sustained biochemically verified abstinence using CO measurement in expired air. Furthermore, patients underwent repeated evaluation of depressive symptoms using BDI-II throughout the treatment.

Limitations

As the psychiatric diagnoses were self-reported by patients, they may sometimes be incorrect or missing (i.e., withheld by the patient), resulting in an underestimation. We assume that any such underestimation would affect the data rather consistently year by year, and therefore would still allow us to track the overall relative change in prevalence over time.

We excluded all records from the years 2005, 2020 and 2021 due to consistency of our dataset: During 2005 the Centre has been established and started work, so data may be incomplete, and in 2020 and 2021 the attendance could be influenced by the COVID-19 epidemic.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that a special attention should be paid to the upward trend of increasing proportion of patients with a mental disorder among smokers seeking intensive tobacco dependence treatment. These individuals should be offered a supportive environment for sharing and treating their psychiatric problems during sensitive screening. The growing proportion of smokers with a mental disorder in specialized Centre forces us to think about adjusting support tailored to these patients. They should not be stigmatised and should be entitled to require more intensive treatment for tobacco dependence alongside their psychiatric treatment. Overall, tobacco dependence treatment should be an integral part of psychiatric care.

Availability of data and materials

The anonymized dataset analysed during the current study is available in the OSF application repository, https://osf.io/rs5fd/?view_only=fd5c0cb924374218a1996c3757f1b02b. In case of the data request from this study, please contact the corresponding author KZ.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- FTCD:

-

Fagerström test for cigarette dependence

- ppm:

-

Parts per million

- PRR:

-

Prevalence rate ratio

References

Lê Cook B, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):172–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.284985.

Talati A, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Changing relationships between smoking and psychiatric disorders across twentieth century birth cohorts: clinical and research implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(4):464–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.224.

Mathews R, Hall WD, Gartner CE. Is there evidence of “hardening” among Australian smokers between 1997 and 2007? Analyses of the Australian National Surveys of Mental Health and Well-Being. Aust N Z J Psychiat. 2010;44:1132–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2010.520116.

Gartner C, Scollo M, Marquart L, Mathews R, Hall W. Analysis of national data shows mixed evidence of hardening among Australian smokers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36(5):408–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00908.x.

Mathews R, Hall WD, Gartner CE. Is there evidence of “hardening” among Australian smokers between 1997 and 2007? Analyses of the Australian national surveys of mental health and well-being. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2010;44(12):1132–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2010.520116.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2018 and 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville (MD). 2020 September 11. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Lipari RN and Van Horn SL. Smoking and mental illness among adults in the United States. In: The CBHSQ Report. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville (MD). 2017 March 30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430654/. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Dickerson F, Schroeder J, Katsafanas E, Khushalani S, Origoni AE, Savage C, et al. Cigarette smoking by patients with serious mental illness, 1999–2016: an increasing disparity. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):147–53.

Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, Orlan C, Graham C, Kakouris G, et al. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48(1):102–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.09.014.

Stolz PA, Wehring HJ, Liu F, Love RC, Ellis M, DiPaula BA, Kelly DL. Effects of cigarette smoking and clozapine treatment on 20-year all-cause & cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(2):351–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9621-4.

Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, Orlan C, Graham C, Kakouris G, Remington G, Gatley J. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48(1):102–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.09.014.

Williams JM, Stroup TS, Brunette MF, Raney LE. Tobacco use and mental illness: a wake-up call for psychiatrists. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(12):1406–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400235.

Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02946.x.

Mackowick KM, Lynch MJ, Weinberger AH, George TP. Treatment of tobacco dependence in people with mental health and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):478–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0299-2.

Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, St Aubin L, McRae T, Lawrence D, Ascher J, Russ C, Krishen A, Evins AE. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30272-0.

Winkler P, Formanek T, Mlada K, Kagstrom A, Mohrova Z, Mohr P, Csemy L. Increase in prevalence of current mental disorders in the context of COVID-19: analysis of repeated nationwide cross-sectional surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e173.

Act No. 65/2017 Coll., On the Protection of Health from the Harmful Effects of Addictive Substances. https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2017-65. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Fiore MC, Jaén CRBT. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline: US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service; 2008.

Králíková E, Zvolská K, Štěpánková L, Pánková A. Tobacco dependence treatment guidelines. Cas Lek Cesk. 2022 Spring;161(1):33–43. PMID: 35354292.

Králíková E, Aschermann M, Dvořák V, Jirkovská J, Hartinger JM, Kališová L et al. [Tobacco Dependence Treatment]. National Portal of Clinical Practice Guidelines, Prague. 2022. https://kdp.uzis.cz/index.php?pg=kdp&id=56. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Centre for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence. Intervention structure. Society for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence, Prague. 2022. https://www.slzt.cz/intervention-structure. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Svicher A, Cosci F, Giannini M, Pistelli F, Fagerström K. Item response theory analysis of fagerström test for cigarette dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;77:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.09.005.

Fagerström K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström test for cigarette dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr137.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in Psychiatric Outpatients Comparison of Beck Depression 1 in Psychiatric Inventories -1A and - Outpatients. J Pers Assess. 2010;67.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck depression inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67.

Rodriguez G. Poisson Models for Count Data. Bernoulli. 2007.

Asharani PV, Ling Seet VA, Abdin E, Siva Kumar FD, Wang P, Roystonn K, Lee YY, Cetty L, Teh WL, Verma S, Mok YM, Fung DSS, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Smoking and Mental Illness: Prevalence, Patterns and Correlates of Smoking and Smoking Cessation among Psychiatric Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155571.

Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Psychiatrists. Smoking and mental health. Royal College of Psychiatrists Council Report CR178. RCP, London. 2013. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/3583/download. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348: g1151.

Stepankova L, Kralikova E, Zvolska K, Pankova A, Ovesna P, Blaha M, Brose LS. depression and smoking cessation: evidence from a smoking cessation clinic with 1-year follow-up. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(3):454–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9869-6.

Yuan S, Yao H, Larsson SC. Associations of cigarette smoking with psychiatric disorders: evidence from a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13807.

Sovinova H, Csemy L, Kernova V. [Tobacco and alcohol use in the Czech Republic: Report on the situation over the last ten years]. National Institute of Public Health, Prague. 2014. https://archiv.szu.cz/uploads/documents/czzp/zavislosti/TabakAlko2004_2013.pdf. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Csemy L, Dvorakova Z, Fialova A, Kodl M, Maly M, Skyvová M. [Tobacco and alcohol use in the Czech Republic 2021 (NAUTA)]. National Institute of Public Health, Prague. 2022. https://archiv.szu.cz/uploads/documents/szu/aktual/NAUTA_2021.pdf. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Prochaska JJ, Das S, Young-Wolff KC. Smoking, mental illness, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;20(38):165–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044618.

Health matters: Smoking and Mental Health. Government of the United Kingdom. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-smoking-and-mental-health/health-matters-smoking-and-mental-health. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank professor Michal Vrablik of the 3rd Medical Department, First Faculty of Medicine and General University Hospital, for enabling our collaboration and providing valuable insights.

Authors would like to thank Vladislava Felbrova and Stanislava Kulovana for taking care of patients and the study administration.

Funding

This research was supported by the Cooperatio Program, research area Metabolic Diseases 207037–1, the Cooperatio Program, research area Health Sciences: Public Health, Hygiene and Epidemiology, Occupational Medicine, and by Grant SGS22/202/OHK4/3 T/17 of the Czech Technical University in Prague.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KZ did preliminary analysis and with LS, AP, ZA and EK they interpreted the patient data. KZ and EK wrote the first version of manuscript with the substantial input of LS, AP, and ZA. AT then shaped up the final version of the manuscript, and AT, GD, JR processed the data and performed statistical analysis. GD and JR prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of General University Hospital in Prague No. 30/13, 49/21, and 1254/22 IS, D. All patients signed the informed consent and agreed with evaluation of their personal data in anonymised form for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zvolska, K., Tichopad, A., Stepankova, L. et al. Increasing prevalence of mental disorders in smokers seeking treatment of tobacco dependence: a retrospective observational study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 621 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05115-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05115-x