Abstract

Background

While adolescent suicidal behaviour (ideation, planning, and attempt) remains a global public health concern, available county-specific evidence on the phenomenon from African countries is relatively less than enough. The present study was conducted to estimate the 12-month prevalence and describe some of the associated factors of suicide behaviour among school-going adolescents aged 12–17 years old in Namibia.

Methods

Participants (n = 4531) answered a self-administered anonymous questionnaire developed and validated for the nationally representative Namibia World Health Organization Global School-based Student Health Survey conducted in 2013. We applied univariate, bivariable, and multivariable statistical approaches to the data.

Results

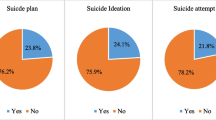

Of the 3,152 analytical sample, 20.2% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 18.3–22.2%) reported suicidal ideation, 25.2% (95% CI: 22.3–28.4%) engaged in suicide planning, and 24.5% (95% CI: 20.9–28.6%) attempted suicide during the previous 12 months. Of those who attempted suicide, 14.6% (95% CI: 12.5–16.9%) reported one-time suicide attempt, and 9.9% (95% CI: 8.1–12.1%) attempted suicide at least twice in the previous 12 months. The final adjusted multivariable models showed physical attack victimisation, bullying victimisation, loneliness, and parental intrusion of privacy as key factors associated with increased likelihood of suicidal ideation, planning, one-time suicide attempt, and repeated attempted suicide. Cannabis use showed the strongest association with increased relative risk of repeated attempted suicide.

Conclusion

The evidence highlights the importance of paying more attention to addressing the mental health needs (including those related to psychological and social wellness) of school-going adolescents in Namibia. While the current study suggests that further research is warranted to explicate the pathways to adolescent suicide in Namibia, identifying and understanding the correlates (at the individual-level, family-level, interpersonal-level, school context and the broader community context) of adolescent suicidal ideations and non-fatal suicidal behaviours are useful for intervention and prevention programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines suicidal behaviour as “a range of behaviours that include thinking about suicide (or ideation), planning for suicide, attempting suicide and suicide itself” [1]. Suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and (repeated) attempted suicide represent important risk factors for suicide mortality in the general population [1,2,3]. Globally, 703,000 suicidal deaths are recorded annually, representing more than one in every 100 deaths in 2019 [4]. Among young persons aged 15–19 years, suicide was the third leading cause of death among girls (after maternal conditions) and the fourth leading cause of death in boys, after tuberculosis – as at the end of 2019 [4]. About 79% of the world’s suicides are recorded in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with the Africa region recording the highest rate – 11.2 per 100,000 people [4, 5]. However, national-level representative data on suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts, and their associated factors are still less than enough to support research-informed intervention and prevention efforts and programmes, particularly in LMICs, including those in Africa [1].

Evidence from a recent global systematic review and meta-analysis suggests varying 12-month prevalence estimates of suicidal behaviour among adolescents: suicide ideation = 14.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 11.6–17.3%), suicidal planning = 7.5% (CI = 4.5–12.1%), and suicide attempt = 4.5% (95% CI = 3.4–5.9%) [6]. Comparatively, pooled regional rates drawing on published data from the World Health Organization Global School-based Student Health Survey (WHO-GSHS) indicate that the 12-month prevalence estimates of adolescent suicidal behaviour in LMICs are higher in the African region: ideation = 21% (95%CI = 20.1–21.0%), suicidal plan = 23.7% (95%CI = 19.1–28.3%), and attempt = 16.3% (95% CI = 8.4–29%) [7,8,9]. Notably, the 12-month median prevalence estimate of adolescent self-harm in Southern sub-Saharan Africa – where Namibia is located – (16.5% interquartile range [IQR] = 10.9–24.0%) is comparable to the overall estimate across the sub-Saharan region (16.9% [IQR] = 11.5–25.5%) [10].

Factors associated with suicidal behaviour among adolescents in LMICs, including those in (sub-Saharan) Africa, have been found to exist at the individual-level (e.g., [female] gender, low self-worth, hopelessness, HIV/AIDS and other chronic medical conditions in adolescents, alcohol and drug [mis]use, depression, and anxiety and other untreated psychiatric conditions) [7, 8, 10, 11], family-level (e.g., parental understanding and support, food insecurity [hunger], conflict with parents, parental divorce, physical abuse victimisation, conflict between parents, child marriage, parental/family poverty) [8, 10, 12], interpersonal-level (e.g., lack of peer support, romantic relationships problems, breakups, sexual abuse victimisation) [8, 10, 12], school context (bullying victimisation, peer support at school, poor school climate, peer suicide or attempted suicide, and poor academic performance, truancy) [8, 12], and the broader community-level – e.g., community violence or war, poverty [10, 12,13,14]. The multi-layered and multi-contextual nature of the factors associated with adolescent suicidal behaviour can be understood within the socio-ecological model. The socio-ecological model provides a helpful framework to understanding and preventing (adolescent) suicidal behaviour in that the model considers an integration of population-specific and general risks and protective factors [1, 15, 16].

Within Southern sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa remains the only country with relatively large data on adolescent self-harm and suicidal behaviour [10, 17,18,19]. Hence, towards contributing evidence to addressing the dearth of research on adolescent suicidal behaviour in Southern sub-Saharan African countries (apart from South Africa), several scholars have explored and published evidence from the WHO-GSHS data accessed from some countries in the sub-region: Botswana [20], Eswatini [14], Malawi [21], Mauritius [22], Mozambique [23, 24], Zambia [25], and Zimbabwe [26]. Thus far, it is only the published study by Peltzer and Pengpid (2017) drawing on the Namibian WHO-GSHS data that reports evidence on suicide attempt [27]. In other words, no peer-reviewed publication is available on the secondary analysis of the country-specific prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation, planning, and (repeated) suicide attempt in the nationally representative school-going adolescents sample (aged 17 years and younger) of the Namibian WHO-GSHS data. It must be noted that the 2013 Namibian WHO-GSHS data is the latest available dataset from the country’s participation in the survey.

Namibia has a youthful population, as persons aged 17 years and younger constitute 43% of the general population [28]. The mean years of schooling in Namibia is 7.2 years [29]. Primary to middle school education, which stretches from grade 1 through 7, is compulsory for all children between the ages of 6 and 16 years, while secondary education remains optional [30]. Namibia is an English-speaking Southern sub-Saharan African country classified as an upper-middle-income country [31], with a Medium Human Development Index rank of 139 [29]. In 2019, the country’s age-standardised, all ages suicide rate was 13.5 per 100,000 people, higher than both the Africa rate (11.2 per 100,00 people) and global average (9.0 per 100, 000 people) [4].

Thus, the present study seeks to analyse the 2013 Namibian WHO-GSHS data on non-fatal suicidal behaviours to address the following research aims:

-

1].

Estimate the 12-month prevalence of suicidal behaviour (ideation, planning, and attempt) among school-going adolescents 12–17 years in Namibia.

-

2].

Describe some of the commonly reported factors at the personal/lifestyle-, family-, school-, and interpersonal relationship-levels associated with suicide ideation, planning, and (repeated) suicide attempt among school-going adolescents (aged 12–17 years) in Namibia. Considering the nature of the data analysed, his study considers suicidal behaviour to comprise suicidal ideation, planning, and attempt – excluding suicidal death.

Methods

Context and data source

This study drew on data from the 2013 Namibia WHO-GSHS. The survey was conducted by WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States in collaboration with the Government of Namibia [32]. The data is publicly available and has been accessed freely for the current study from the WHO website [32].

Study design and sampling

The WHO-GSHS is a national representative cross-sectional survey conducted to assess behavioural health factors amongst school-going adolescents (mainly aged 13 to 17) in participating WHO member countries [33]. Data was collected using a validated self-administered questionnaire consisting of items assessing a wide range of personal lifestyle (e.g., alcohol and drug use), family relationships (e.g., parental supervision and understanding), and school environment variables (e.g., truancy and bullying) [33]. Prior to the data collection, ethical approval was sought from relevant authorities as well as consent from parents/guardians of adolescents. The 2013 Namibia GSHS targeted students in grades 7–12 which is typically attended by students aged 13–17 years. A two-stage sampling approach was used for data collection. In the first stage, a cluster of schools were randomly selected from a list of all schools in Namibia using a probability proportionate to enrollment size method. This process resulted in a list of eligible and nationally representative schools. The second stage involved the random sampling of classrooms from these eligible schools, making all students in the selected classes eligible to participate. Students who volunteered to participate were then handed an anonymised computer scannable questionnaire to complete. A total of 4531 students aged 13-18years participated in the Namibia GSHS. The school response rate was 100%; that of students was 89%, while the overall response rate was 89%. The reporting of the current study was guided by the recommendations of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [34].

Measures

Outcome variables

Three domains of suicidal behaviour namely suicide ideation, planning and attempt were considered as the outcome variables for this study. The three domains were each assessed using a single-item question. Suicide ideation was measured with, “during the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”, suicide planning with, “during the past 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?” and attempt with “during the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”. The responses for suicide ideation and plan were, “Yes = 1” and “No = 0” while that of attempt required students to indicate the number of times with “0”, “1”, “2 or 3”, “4 or 5”, and “6 or more times”. Guided by the GSHS recoding procedures [33], the suicide attempt variable was treated as a binary variable assigning “0” to no attempt and “1” to one or more attempts. For the purposes of examining factors responsible for repeated suicide attempts, the attempt variable was subsequently reclassified into three categories namely, no attempt, one-time attempt, and repeated attempts. Therefore, responses of adolescents who chose “1” for suicide attempt was recoded into the one-time attempt category and that of adolescents who chose “2 and above” into the repeated attempts category. Coding of variables included in this study (i.e., demographic variables, exposure factors, and missing data) are presented as supplementary material (e-Table 1).

Exposure variables

Participants’ demographic characteristics, mental health and lifestyle factors, interpersonal factors, school-level factors as well as family-level factors were selected as exposure variables in this study. Besides performing bivariable analyses to assess the relationships between the exposure and outcomes variables, the selection of these exposure variables was based on evidence from previous studies within sub-Saharan Africa drawing data from the WHO-GSHS [14, 27, 35,36,37]. Examples of the specific factors include age, school grade, gender, cannabis use, loneliness, anxiety, and alcohol use. Complete details of the variables, their groupings, survey questions and coding can be found in supplementary material (e-Table 1).

Statistical analyses

Reporting of the statistical analyses plan in this study is informed by the Statistical Analyses and Methods in the Published Literature (SAMPL) guidelines [38]. We limited the analysis to participants aged 12 to 17 years for two reasons: first, most of the participants were within this age range, and second, data on the precise ages below and above this age range were not available. Age and gender distribution across the analytical sample is presented as supplementary material (e-Table 2). Statistical analyses involving univariate, bivariate and multivariate testing were conducted in Stata 14.0 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Prior to conducting these tests, clusters, stratification, and sample weights characteristic of data collected with complex designs were adjusted to account for possible analytical errors and make appropriate inferences [39]. Following from this, univariate analysis computing frequencies, proportions and relevant 95% confidence intervals of all study variables was done. Chi-square tests (χ2) of independence were performed to examine the association between the exposure and outcomes variables. Multivariate analyses with logistic regression and multinomial logistic regression were then conducted in two steps. Step 1: Logistic regression was performed to assess the sociodemographic factors and exposures variables associated with suicidal ideation, planning and attempt. Step 2: We performed a multinomial logistic model assessing the factors associated with repeated suicide attempt (keeping the base at ‘no attempt’). Given the presence of sparse data only exposure variables that reached statistical significance in the binary logistic regression models were included in the multinomial logistic model. Age, gender and school grade were included as covariates in the multivariable analyses. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of 0.05. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) are reported for each logistic model and adjusted relative risk ratio (ARRR) for the multinomial logistic model. Given the arbitrary nature of the alpha (p < 0.05), the significance of each analysis was also determined based on CIs and their clinical importance [40, 41]. Missing responses or incomplete data on key variables were excluded from the final analysis (e-Table 1).

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 3152 in-school adolescents comprising 1380 (44.3%) male and 1772 (55.7%) females were included as analytical sample in the secondary analysis for this study. The average age of these adolescents was M = 15.1 (SD = 1.4) and most of them were in grade 10–12 (60.5%). Regarding mental health and lifestyle factors, approximately 14 and 13% of adolescents had experienced loneliness and anxiety respectively and about 36% had spent 3 or more hours a day engaged in leisure time or sedentary behaviour. Additionally, about 29% and 5% had use alcohol and cannabis in the past month, respectively.

Prevalence estimates

Table 1 presents comparable 12-month prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation (20.2% [95% CI = 18.3–22.2%]), plan (25.2% [95% CI = 22.3–28.4%]), one-time attempt (14.6% (95% CI = 12.5–16.9%]) and repeated attempt (9.9% (95% CI = 8.1–12.1%]) across the total analytic sample. Overall, 24.5% (95% CI = 20.9–28.6%) of the analytic sample reported attempted suicide during the previous 12 months. Similarly, the 12-month prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation, plan, one-time and repeated attempt were comparable between boys and girls, as the CIs of these estimates overlapped.

Bivariate associations

As shown in Table 2, most of the exposure variables were significantly related to suicidal behaviour. Of the two demographic factors (gender, and school grade) included in the study, only, school grade was significantly related to suicidal behaviour. A high proportion of students in grade 6–9 (compared to students in grades 10–12) reported suicide ideation, plan and attempt during the previous 12 months. Among the mental health and lifestyle factors, loneliness, anxiety, alcohol use and cannabis use were all significantly related to suicidal behaviour. Leisure-time sedentary behaviour was significantly related to only suicidal ideation (χ2 = 4.6, df = 1, p = 0.01). Under the interpersonal factors, being sexually active and physical fight were related to suicide behaviour. Having a close friend was significantly related to suicide plan. Concerning school-level factors, a significant proportion of students who were physically attacked, truant and were victims of bullying reported experiences of suicidal behaviour. Some significant associations were also found among the family-related factors (e.g., intrusion of privacy by parents, food insecurity, and parental supervision) and suicidal behaviour. Notably, food insecurity and parental intrusion of privacy were both related to all the domains of suicidal behaviour examined.

Multivariate associations

Tables 3 and 4 show the findings of the adjusted logistic regression models and multinomial models respectively.

Logistic regression

As presented in Table 3, the most important exposure factors contributing to the increased odds of all the domains of suicide included grade in school, loneliness, physical attack and parental intrusion of privacy. Other variables including age, anxiety, leisure-time sedentary behaviour, cannabis use, physical fight, bullying victimisation, and parental monitoring were related to at least one form of suicide behaviour. For instance, sedentary behaviour was associated with increased the odds of only suicidal ideation (AOR = 1.36, 95% CI:1.08, 1.72, p = 0.009), while parental monitoring was related to reduced odds of attempted suicide (AOR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57, 0.94, p = 0.001). Interestingly, although gender, alcohol use, being sexually active, number of close friends, truancy, peer support, parental understanding, and food insecurity were associated with each of the suicidal behaviour outcomes, none of these associations reached the desired threshold of statistical significance (Table 3).

Multinomial logistic regression

As shown in Table 4, five factors (physical attack victimisation, bullying victimisation, loneliness, parental intrusion of privacy, and grade in school) were associated with the likelihood of both one-time attempt and repeated attempted suicide during the previous 12 months. Specifically, physical attack victimisation, bullying victimisation, loneliness, and parental intrusion of privacy were associated with increased likelihood of both one-time attempt and repeated attempted suicide. However, adolescents in grades 10–12 (compared to those in grades 6–9) had reduced relative risk of reporting one-time attempt (ARRR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.36, 0.70, p < 0.001) or repeated attempt (ARRR = 0.51, 95% CI:0.35, 0.75, p = 0.001). It is also worthy of mention that while the likelihood association between cannabis use and one-time suicide attempt did not reach the desired threshold of statistical significance, comparatively, the likelihood association between cannabis use and repeated suicide attempt showed the strongest statistical and clinical importance (ARRR = 3.72, 95% CI: 2.08, 6.65, p < 0.001) between the two statistical models. Put differently, students who used cannabis were at about three times increased relative risk of repeated attempted suicide during the previous 12 months, compared to students who did not use cannabis.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study sought to describe the 12-month prevalence estimates of suicidal behaviour (ideation, planning, and [one-time and repeated] attempts) and associated factors among school-going adolescents aged 12–17 years in Namibia, drawing on the 2013 Namibian WHO-GSHS. In summary, the current study has two key findings. First, comparable estimates of suicidal behaviour were found between boys and girls, with about 2 in 10 adolescents reporting suicidal ideation, planning, or attempt in the previous 12 months. Approximately, 1 in 20 students reported repeated attempted suicide during the previous 12 months. Secondly, physical attack victimisation, bullying victimisation, loneliness, and parental intrusion of privacy were associated with increased likelihood of suicidal ideation, planning, one-time suicide attempt and repeated attempted suicide. Adolescents in higher grades (grades 10–12), compared to those in lower grades (grades 6–9), had reduced relative risk of reporting one-time attempt or repeated attempts at suicide. Cannabis use was associated with increased relative risk of repeated attempted suicide.

The 12-month prevalence estimates of suicidal behaviour found in the current study are comparable to those found generally among school-going adolescents within the (sub-Saharan) African region, where estimates of suicidal ideations, planning and attempt range from 20.1 to 29% [7,8,9]. Beyond the similarity of the estimates of this study to those reported earlier from other Southern African countries – e.g., Eswatini, Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa – [14, 19, 21, 23, 24], the evidence regarding comparable estimates between boys and girls have also been reported from other Southern African countries and sub-Saharan Africa in general [10, 21]. The cross-national similarity of the estimates is to be expected, considering that the data are drawn from the WHO-GSHS conducted in the respective countries using the same measures and definitions of included variables. The lack of significant gender differences in the estimates of suicidal behaviour could be pointing to the possibility that, perhaps, the factors presenting as risks are comparably difficult for both school-going boys and girls in Namibia. This finding could also be supporting the emerging evidence that self-harm and suicidal behaviour are not neatly differentiated between boys and girls within sub-Saharan Africa [10]. Taken together, this evidence could be underscoring the importance of universal intervention and prevention efforts focused on suicidal behaviour in both school-going adolescent boys and girls in Namibia.

We found physical attack victimisation, bullying victimisation, loneliness, and parental intrusion of privacy to be significantly associated with increased likelihood of suicidal ideation, planning, one-time suicide attempt and repeated attempted suicide. Cannabis use was associated with increased relative risk of (repeated) attempted suicide. Global and regional systematic reviews and meta-analyses [7, 8, 10, 12, 42] and recent primary studies drawing data mainly from the WHO-GSHS [14, 21, 23, 36, 37, 43, 44] have also identified these factors to be critical in school-going adolescent suicidal tendencies and behaviours.

Further, within the lens of the socio-ecological model, our finding supports the multi-factorial, multi-layered and multi-contextual nature of the factors associated with suicidal behaviour among adolescents [15, 16]. In broader terms, the identified key associated factors of suicidal behaviour among adolescents in the current study (i.e., physical attack victimisation, bullying victimisation, and parental intrusion of privacy) support evidence in the literature that exposure to (longstanding) interpersonal social adversities and relational difficulties occurring in the family, school or within peer relationships contribute to suicidal behaviour among young people [10, 45, 46]. Besides being a common phenomenon, bullying victimisation has a strong positive association with involvement physical fighting and other interpersonal adversities among school-going adolescents in Namibia [47, 48]. Considered as an antecedent of suicidal thoughts and behaviour, social adversities (e.g., physical attack victimisation, and bullying victimisation) result in internalising problems, often leading to lowered self-esteem, self-blame, and self-dislike, which in turn heighten the vulnerability to self-harming thoughts and behaviours in adolescents [49].

Recent literature is replete with evidence that in both high-income countries and LMICs, lifestyle factors, particularly health risk behaviours (e.g., cannabis smoking, alcohol use) and – untreated – mental health problems (e.g., loneliness, anxiety, depression) have strong association with suicidal behaviour among adolescents[11, 42, 44, 50,51,52]. Although cannabis possession and use are illegal in Namibia, national-level estimates suggest that among school-going adolescents 6.6% boys and 4% girls report having used cannabis during the previous month [53] – a clear indication that there are lapses and problems in the implementation of the law [54]. What is not readily clear from the current study is whether the participants’ cannabis use was a coping strategy for their adverse mental health experiences (e.g., loneliness or anxiety) or for another purpose. Nonetheless, there is evidence to suggest that substance (cannabis or alcohol) use has negative – mental – health outcomes among adolescents. Besides underlying increased susceptibility to brain damage in the long-term, cannabis use impairs judgement and memory, increases impulsivity and negative mood, and potentially complicates the natural course of loneliness, anxiety, and depression – which in turn elevate the risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviour among adolescents [51, 55,56,57,58].

Our finding that school-going adolescents in higher grades, compared to those in lower grades, have reduced relative risk of reporting one-time or repeated attempts at suicide supports earlier evidence from South Africa [59], but it is inconsistent with a recent finding from Ghana, where no significant association was observed between school grade and suicidal behaviour [60]. Whereas explanations for this school grade difference are not readily clear from the Southern African context, perhaps, in Namibia, curriculum-based functional mental health literacy could be suggested. Among other aims, the Namibian school curriculum seeks “to foster the highest moral, ethical and spiritual values such as integrity, responsibility, equality, and reverence for life” [30]. Maybe, the value of ‘reverence for life’ – which essentially proscribes and eschews suicidal thoughts and actions [61] – might have been more actionably consolidated in students in upper school grades than those in lower grades. Beyond this speculation, further studies are needed to understand this differentiation of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in terms of school grade in Namibia but also within the general (Southern) sub-Saharan African context.

While the factors showing significant associations with suicidal behaviour (including repeated attempted suicide) are identified, it is also imperative to comment on the (exposure) variables reported to be important in the literature but showed no significant associations with the outcomes in the current study. Interestingly, in the current study, although alcohol use, being sexually active, number of close friends, truancy, peer support, parental understanding, and food insecurity were associated with each of the suicidal behaviour outcomes, none of these associations reached the desired threshold of statistical significance. While we suspect sparse data to account for the lack of statistical significance, we believe future studies involving relatively large responses to each of these data items will contribute to clarifying the statistical and clinical significance of their associations with school-going adolescent suicidal behaviour in Namibia.

This study has identified the key factors associated with adolescent suicidal behaviours to exist mainly at the individual level/ (e.g., loneliness, anxiety, cannabis use), within school (e.g., bullying victimisation, school grade), family (e.g., intrusion of privacy by parents, parental monitoring), and community context (e.g., physical attack victimisation). The implication of the multi-ecological nature of the key evidence for practice is that intervention and prevention efforts must be designed with a multi-sectoral and multi-layered orientation. For example, while the initiation (or improvement of existing) anti-alcohol and substance use and anti-bullying polices are needed to enhance school social climate, community-level training for supportive parenting can be designed for families with adolescents. Similarly, while parents and significant others living with adolescents need to be observant regarding the identification of warning signs of potential adolescent suicidal behaviours, the Namibian Ministry of Education could consider including mental health literacy and help-seeking lessons in the curriculum for high schools – this would contribute to improving help-seeking and self-care behaviours among school-going adolescents at risk of self-harm and suicidal tendencies and other emotional crises, including loneliness, anxiety and depression.

Strengths and Limitations

A critical significance of this study is that it contributes to addressing the problem of dearth research on suicidal behaviour among adolescents in Namibia. Data on adolescent mental health (outcomes) are still insufficient to inform policy, intervention efforts, and prevention programmes in Namibia [62]. In particular, data on self-harm and suicidal behaviours among (both school-going and out-of-school) adolescents in Namibia are less than enough [10, 63]. Additionally, this study contributes broadly to advance our knowledge and understanding of the prevalence and associated factors of suicidal behaviour among in-school adolescents in Namibia in that the study draws on a relatively large data accessed from a nationally representative sample.

Beyond these strengths, there are noteworthy limitations of this study. The findings of the study should be generalised with caution, as the key evidence may not necessarily apply to out-of-school adolescents. While the study sample excludes students who were absent on the day of the survey, evidence suggests that the average annual dropout rate in Namibia ranges between 3 and 10.4% [64]. The one-time cross-sectional survey design used for the WHO-GSHS implies that the outcome and exposure variables were measured at the same time point, making it impossible to identify sequence, temporal link, and causal relationship between the exposure and outcome variables. Thus, consistent with recommendations by recent studies from of other countries within the continent [10, 13, 65], future studies using more robust approaches, including longitudinal designs and carefully designed qualitative studies are needed for contextually nuanced understanding of self-harm and suicidal behaviours among adolescents in Namibia and (sub-Saharan) Africa generally.

Notably, in the current study, it is not clear why the estimates of suicidal planning and attempt are higher than suicidal ideation. Similar evidence has been reported from other sub-Saharan African countries drawing on the WHO-GSHS data – e.g., Benin, Ghana, Liberia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone [21, 37, 66,67,68]. However, this evidence is unconventional, counterintuitive, and not in keeping with the suicide process or pathway model [69, 70], which superlatively suggests that, typically, estimates of ideation are expected to be highest, followed by estimates of planning, then estimates of attempt. Perhaps, the use of a single-item measures in the WHO-GSHS to assess these outcomes could account for this unconventional finding. As cautioned elsewhere, the use of single-item measure to assess suicidal ideation, planning, and attempt must be interpreted cautiously, as single-item measures typically result in misclassification of suicidal behaviours and higher estimates [71]. Specially, we also suspect that the lower estimate of suicidal ideation – relative to suicidal attempt – in the current study may be due to impulsivity. There is evidence from high-income countries to suggests that impulsivity may result in the onset of suicidal attempt among adolescents, even in the absence of prior suicidal ideation [72, 73].

Conclusion

The evidence of this study adds to the literature on non-fatal suicidal behaviour among school-going adolescents in (sub-Saharan) Africa, but also underscores the marked estimates of suicide ideation, planning, and (repeated) suicide attempt among school-going adolescents (aged 12–17 years) in Namibia. The relatively high prevalence estimates and multi-layered correlates (at the individual-level, family-level, interpersonal-level, school context and the broader community context) contribute to our understanding of adolescent suicide in Namibia. The evidence highlights the importance of paying more attention to addressing the mental health needs (including those related to psychological and social wellness) of school-going adolescents in Namibia. While the current study suggests that further research is warranted to explicate the pathways to adolescent suicide in Namibia, identifying and understanding the correlates of adolescent suicidal ideations and non-fatal suicidal behaviours are useful for intervention and prevention programmes.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are freely available from the WHO website: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/478. The 2013 Namibia GSHS questionnaire is also available freely on the WHO’s website: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/478#metadata-questionnaires.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- GSHS:

-

Global School-based Student Health Survey

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014.

Demesmaeker A, Chazard E, Hoang A, Vaiva G, Amad A. Suicide mortality after a nonfatal suicide attempt: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2022;56(6):603–16.

Fazel S, Runeson B. Suicide. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):266–74.

WHO. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Suicide. : one person dies every 40 seconds [[https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2019-suicide-one-person-dies-every-40-seconds]]

Lim K-S, Wong CH, McIntyre RS, Wang J, Zhang Z, Tran BX, Tan W, Ho CS, Ho RC. Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4581.

Biswas T, Scott JG, Munir K, Renzaho AM, Rawal LB, Baxter J, Mamun AA. Global variation in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety and their correlates among adolescents: a population based study of 82 countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100395.

Li L, You D, Ruan T, Xu S, Mi D, Cai T, Han L. The prevalence of suicidal behaviors and their mental risk factors among young adolescents in 46 low-and middle-income countries. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:847–55.

Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2019;3(4):223–33.

Quarshie EN, Waterman MG, House AO. Self-harm with suicidal and non-suicidal intent in young people in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–26.

Orri M, Scardera S, Perret LC, Bolanis D, Temcheff C, Séguin JR, Boivin M, Turecki G, Tremblay RE, Côté SM. Mental health problems and risk of suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents.Pediatrics2020, 146(1).

Ati NA, Paraswati MD, Windarwati HD. What are the risk factors and protective factors of suicidal behavior in adolescents? A systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychiatric Nurs. 2021;34(1):7–18.

Orri M, Ahun MN, Naicker S, Besharati S, Richter LM. Childhood factors associated with suicidal ideation among south african youth: a 28-year longitudinal study of the birth to twenty plus cohort. PLoS Med. 2022;19(3):e1003946.

Quarshie EN-B, Atorkey P, García KPV, Lomotey SA, Navelle PL. Suicidal Behaviors in a Nationally Representative Sample of School-Going Adolescents Aged 12–17 Years in Eswatini.Trends in Psychology2021:1–30.

Cramer RJ, Kapusta ND. A social-ecological framework of theory, assessment, and prevention of suicide.Frontiers in Psychology2017:1756.

Shagle SC, Barber BK. A social-ecological analysis of adolescent suicidal ideation. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65(1):114–24.

James S, Reddy SP, Ellahebokus A, Sewpaul R, Naidoo P. The association between adolescent risk behaviours and feelings of sadness or hopelessness: a cross-sectional survey of south african secondary school learners. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(7):778–89.

Reddy S, James S, Sewpaul R, Sifunda S, Ellahebokus A, Kambaran NS, Omardien RG. Umthente uhlaba usamila: the 3rd south african national youth risk behaviour survey 2011. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council; 2013.

Shilubane HN, Ruiter RA, van den Borne B, Sewpaul R, James S, Reddy PS. Suicide and related health risk behaviours among school learners in South Africa: results from the 2002 and 2008 national youth risk behaviour surveys. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–14.

Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Elimam DM, Gaylor E, Jayaraman S. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and physical fighting: A comparison between students in Botswana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia and the United States. Public health yearbook, 2010. edn. Edited by Merrick J:Nova Biomedical Books; 2012:pp. 233–245.

Shaikh MA, Lloyd J, Acquah E, Celedonia KL, Wilson L. Suicide attempts and behavioral correlates among a nationally representative sample of school-attending adolescents in the Republic of Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–8.

Hoogstoel F, Samadoulougou S, Lorant V, Kirakoya-Samadoulougou F. A latent class analysis of health lifestyles in relation to suicidality among adolescents in Mauritius. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6934.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Suicide attempt and associated factors among in-school adolescents in Mozambique. J Psychol Afr. 2020;30(2):130–4.

Seidu A-A, Amu H, Dadzie LK, Amoah A, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Acheampong HY, Kissah-Korsah K. Suicidal behaviours among in-school adolescents in Mozambique: cross-sectional evidence of the prevalence and predictors using the Global School-Based Health Survey data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0236448.

Muula AS, Kazembe L, Rudatsikira E, Siziya S. Suicidal ideation and associated factors among in-school adolescents in Zambia. Tanzan J Health Res. 2007;9(3):202–6.

Rudatsikira E, Siziya S, Muula AS. Suicidal ideation and associated factors among school-going adolescents in Harare, Zimbabwe. J Psychol Afr. 2007;17(1–2):93–7.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Lifestyle and mental health among school-going adolescents in Namibia. J Psychol Afr. 2017;27(1):69–73.

UNICEF. Young People in Namibia: an analysis of the 2011 Population & Housing Census. Windhoek: UNICEF Namibia; 2014.

UNDP. Human Development Report 2021/2022. Uncertain times, unsettled lives: shaping our future in a transforming world. New York: UNDP; 2022.

UNESCO. International Bureau of Education: World data on education: Namibia. Geneva, Switzerland: UNESCO-IBE; 2010.

World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Country classification [[https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups]]]

Global School-Based Student Health Survey 2013. : Namibia, 2013 [[https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/478]]

Global school-based. student health survey [https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey]

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behaviour among adults in Malawi: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey in 2017. Int J Mental Health Syst. 2021;15(1):1–8.

Quarshie EN-B, Andoh-Arthur J. Suicide attempts among 1,437 adolescents aged 12–17 years attending junior high schools in Ghana. Crisis; 2020.

Quarshie EN-B, Onyeaka HK, Oppong Asante K. Suicidal behaviours among adolescents in Liberia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Lang TA, Altman DG. Basic statistical reporting for articles published in biomedical journals: the “Statistical analyses and methods in the published Literature” or the SAMPL Guidelines. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):5–9.

West BT, Sakshaug JW, Aurelien GAS. How big of a problem is analytic error in secondary analyses of survey data? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0158120.

Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, Carlin JB, Poole C, Goodman SN, Altman DG. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(4):337–50.

Sterne JA, Smith GD. Sifting the evidence - what’s wrong with significance tests? Phys Ther. 2001;81(8):1464–9.

Abio A, Owusu PN, Posti JP, Bärnighausen T, Shaikh MA, Shankar V, Lowery Wilson M. Cross-national examination of adolescent suicidal behavior: a pooled and multi-level analysis of 193,484 students from 53 LMIC countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57:1603–13.

Pandey AR, Bista B, Dhungana RR, Aryal KK, Chalise B, Dhimal M. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adolescent students in Nepal: findings from Global School-based Students Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0210383.

Tetteh J, Ekem-Ferguson G, Swaray SM, Kugbey N, Quarshie EN-B, Yawson AE. Marijuana use and repeated attempted suicide among senior high school students in Ghana: Evidence from the WHO Global School-Based Student Health Survey, 2012.General Psychiatry2020, 33(6).

Fortune S, Stewart A, Yadav V, Hawton K. Suicide in adolescents: using life charts to understand the suicidal process. J Affect Disord. 2007;100(1–3):199–210.

Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373–82.

Davis LE, Abio A, Wilson ML, Shaikh MA. Extent, patterns and demographic correlates for physical fighting among school-attending adolescents in Namibia: examination of the 2013 Global School-based Health Survey. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9075.

Rudatsikira E, Siziya S, Kazembe LN, Muula AS. Prevalence and associated factors of physical fighting among school-going adolescents in Namibia. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6(1):1–5.

Page RM, West JH. Suicide ideation and psychosocial distress in sub-saharan african youth. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(2):129–41.

Carvalho AF, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Kloiber S, Maes M, Firth J, Kurdyak PA, Stein DJ, Rehm J, Koyanagi A. Cannabis use and suicide attempts among 86,254 adolescents aged 12–15 years from 21 low-and middle-income countries. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56(1):8–13.

Fresán A, Dionisio-García DM, González-Castro TB, Ramos-Méndez M, Castillo-Avila RG, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Juárez-Rojop IE, López-Narváez ML, Genis-Mendoza AD, Nicolini H. Cannabis smoking increases the risk of suicide ideation and suicide attempt in young individuals of 11–21 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Journal of Psychiatric Research2022.

Tetteh J, Ekem-Ferguson G, Quarshie EN-B, Swaray SM, Ayanore MA, Seneadza NAH, Asante KO, Yawson AE. Marijuana use and suicidal behaviours among school-going adolescents in Africa: assessments of prevalence and risk factors from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey.General Psychiatry2021, 34(4).

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Cannabis and amphetamine use and associated factors among school-going adolescents in nine african countries. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2018;27(2):112–8.

Cannabis in Namibia – Laws, Use, and History, [[. https://sensiseeds.com/en/blog/countries/cannabis-in-namibia-laws-use-history/]]

Borges G, Loera CR. Alcohol and drug use in suicidal behaviour. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(3):195–204.

Paruk S, Burns JK. Cannabis and mental illness in adolescents: a review. South Afr Family Pract. 2016;58(sup1):18–S21.

Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219–27.

Sideli L, Quigley H, La Cascia C, Murray RM. Cannabis use and the risk for psychosis and affective disorders. J Dual Diagnosis. 2020;16(1):22–42.

Shilubane HN, Ruiter RA, Bos AE, van den Borne B, James S, Reddy PS. Psychosocial determinants of suicide attempts among black south african adolescents: a qualitative analysis. J Youth Stud. 2012;15(2):177–89.

Quarshie EN-B, Odame SK. Suicidal ideation and associated factors among school-going adolescents in rural Ghana. Current Psychology 2021(advance online publication):1–14.

Gyekye K. African cultural values. An introduction. Accra, Ghana: Sankofa publishing company; 2003.

WHO. Adolescent health in Namibia. Windhoek, Namibia: WHO Regional Office for Africa; 2018.

Ministry of Health and Social Services. National Multisectoral Strategic Plan for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in Namibia 2017/18–2021/22. Windhoek, Namibia: Ministry of Health and Social Services; 2017.

Nekongo-Nielsen H, Mbukusa NR, Tjiramba E. Investigating factors that lead to school dropout in Namibia. The Namibia CPD Journal for Educators. 2015;2(1):99–118.

Quarshie EN, Waterman MG, House AO. Adolescent self-harm in Ghana: a qualitative interview-based study of first-hand accounts. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–14.

Asante KO, Kugbey N, Osafo J, Quarshie EN-B, Sarfo JO. The prevalence and correlates of suicidal behaviours (ideation, plan and attempt) among adolescents in senior high schools in Ghana. SSM-population Health. 2017;3:427–34.

Randall JR, Doku D, Wilson ML, Peltzer K. Suicidal behaviour and related risk factors among school-aged youth in the Republic of Benin. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e88233.

Asante KO, Quarshie EN-B, Onyeaka HK. Epidemiology of suicidal behaviours amongst school-going adolescents in post-conflict Sierra Leone. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:989–96.

Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12(1):307–30.

Millner AJ, Lee MD, Nock MK. Describing and measuring the pathway to suicide attempts: a preliminary study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2017;47(3):353–69.

Hom MA, Joiner TE Jr, Bernert RA. Limitations of a single-item assessment of suicide attempt history: implications for standardized suicide risk assessment. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(8):1026.

Anestis MD, Soberay KA, Gutierrez PM, Hernández TD, Joiner TE. Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2014;18(4):366–86.

May AM, Klonsky ED. Impulsive” suicide attempts: what do we really mean? Personality Disorders: Theory Research and Treatment. 2016;7(3):293.

Acknowledgements

We also thank the Namibian Ministries of Health and Social Services and Education, and WHO and its partners for making freely available the data from the 2013 Namibian WHO-GSHS. Lastly, but more importantly, we also thank all the students who contributed data for this survey.

Funding

The authors received no financial support or specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors, for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ENBQ, NEYD, and KOA conceived, designed and organised the study. ENBQ, and NEYD curated the data and performed the statistical analysis; and ENBQ and KOA contributed to the interpretation of the data. ENBQ and NEYD drafted the manuscript, and KOA critiqued the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. ENBQ serves as guarantor for the contents of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ENBQ is an Associate Editor of BMC Psychiatry. The rest of the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The 2013 Namibian WHO-GSHS was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Namibian Ministry of Health and Social Services. The study was supported by WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Policies laid out by the Ministry of Education regarding consent procedures for participation in students surveys were followed including detachment of identifier information. Official written permissions were obtained from Namibian Ministry of Health and Social Services, and the Ministry of Education, the selected schools, and classroom teachers. Written informed consent were obtained from students, while an additional written parental consent was obtained from parents of participants aged younger than 18 years. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Quarshie, E.NB., Dey, N.E. & Oppong Asante, K. Adolescent suicidal behaviour in Namibia: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and correlates among 3,152 school learners aged 12–17 years. BMC Psychiatry 23, 169 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04646-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04646-7