Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed a serious health risk, especially in vulnerable populations. Even before the pandemic, people with mental disorders had worse physical health outcomes compared to the general population. This umbrella review investigated whether having a pre-pandemic mental disorder was associated with worse physical health outcomes due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Following a pre-registered protocol available on the Open Science Framework platform, we searched Ovid MEDLINE All, Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL, and Web of Science up to the 6th of October 2021 for systematic reviews on the impact of COVID-19 on people with pre-existing mental disorders. The following outcomes were considered: risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 infection, risk of severe illness, COVID-19 related mortality risk, risk of long-term physical symptoms after COVID-19. For meta-analyses, we considered adjusted odds ratio (OR) as effect size measure. Screening, data extraction and quality assessment with the AMSTAR 2 tool have been done in parallel and duplicate.

Results

We included five meta-analyses and four narrative reviews. The meta-analyses reported that people with any mental disorder had an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR: 1.71, 95% CI 1.09–2.69), severe illness course (OR from 1.32 to 1.77, 95%CI between 1.19–1.46 and 1.29–2.42, respectively) and COVID-19 related mortality (OR from 1.38 to 1.52, 95%CI between 1.15–1.65 and 1.20–1.93, respectively) as compared to the general population. People with anxiety disorders had an increased risk of SAR-CoV-2 infection, but not increased mortality. People with mood and schizophrenia spectrum disorders had an increased COVID-19 related mortality but without evidence of increased risk of severe COVID-19 illness. Narrative reviews were consistent with findings from the meta-analyses.

Discussion and conclusions

As compared to the general population, there is strong evidence showing that people with pre-existing mental disorders suffered from worse physical health outcomes due to the COVID-19 pandemic and may therefore be considered a risk group similar to people with underlying physical conditions. Factors likely involved include living accommodations with barriers to social distancing, cardiovascular comorbidities, psychotropic medications and difficulties in accessing high-intensity medical care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected most of the population worldwide. Disadvantaged population groups are thought to have suffered the most, with possibly among those, people affected by mental disorders. The physical health repercussions have been a particular point of concern, as many known risk factors for severe COVID-19 illness course and COVID-19 related mortality are common in people with mental disorders [1,2,3]. Firstly, it is unclear whether this population, or specific subgroups, had an increased risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus than the general population [4, 5]. Shared living accommodations represented contexts in which adhering to social distancing might have been not possible or difficult. Secondly, there has been a focus on the disease course in people with mental disorders. Obesity, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease are common in this population [6, 7]. In addition to that, many psychotropic medications have the potential of a detrimental effect on the respiratory function [8, 9]. Given these premises, it seems highly relevant to assess if and how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the physical health of people with pre-existing mental disorders. Against this background, an umbrella review was performed aiming to summarize evidence from systematic reviews (SR) and meta-analyses (MAs). This work builds on a wider project of evidence synthesis on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, performed to inform a WHO Scientific Brief [10].

Methods

Umbrella review design

We followed published guidelines on performing umbrella reviews [11,12,13]. An umbrella review consists of a systematic search and assessment of systematic reviews on a specific research question. This allows for the comparison of results of clinical outcomes and provides a clear picture on broad healthcare areas, possibly revealing whether the evidence base is consistent or contradictory. We registered a protocol to define the research methodology to inform the WHO Scientific brief that is publicly available on the Open Science Framework platform [14]. The present work is based on the ‘Question 3 - Are people living with pre COVID-19 existing mental health disorders at (increased) risk of severe illness and mortality and/or of contracting SARS-CoV-2 compared to any other population?’ of the protocol, with the addition of focusing on estimates that have adjusted for confounding.

Literature search and study selection

An information specialist performed a systematic search on Ovid MEDLINE All, Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL, and Web of Science, from December 31, 2019 until October 6, 2021, using a search strategy based on a combination of keywords and text words for reviews, COVID-19, and mental disorders or problems. The search strategy can be found in the supplementary material. This search was designed to inform a wide panel of different research questions on COVID-19 and mental health. We deduplicated search results using Endnote software [15]. Entries were divided into groups, each screened in parallel and independently by two different authors using Rayyan [16]. In case of disagreement, records were conserved. The full text of the remaining articles was assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, again in duplicate and independently. Disagreement was resolved by discussion or with a senior review author.

Eligibility criteria and data extraction

We considered for inclusion reviews that: (1) were systematic, as defined by having a systematic search on at least one bibliographic database, explicitly reporting primary studies selection criteria and providing a list and synthesis of included studies; (2) considered as primary studies either cohort or cross-sectional or case-control studies; (3) have been published in a peer-reviewed journal; (4) compared people with pre-existing mental disorders (i.e., with a diagnosis of mental disorder established before the pandemic onset) with those without a pre-existing mental disorder; and (5) assessed at least one of the following outcomes: (a) risk of contracting SARS-Cov-2 infection, (b) risk of severe COVID-19 illness, (c) risk of long-term physical symptoms after COVID-19 illness, (d) mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infection. For the outcome ‘risk of severe illness’, we considered definitions as provided by original systematic reviewers, or proxy outcomes such as hospitalization. We did not exclude reviews on the basis of language of publication. In the case of reviews considering several pandemics, we planned to include only those that reported separated data for the COVID-19 pandemic. We considered systematic reviews independently of whether a meta-analysis was performed. Two authors independently and in parallel extracted the following data: author, date of publication, timeframe covered by the search, population and comparator, design of included studies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcomes, risk of bias assessment strategy, how exposure to SARS-CoV-2 was established, number of included studies and participants, and outcomes of interest with I2 statistic as a measure of heterogeneity. In terms of meta-analysis, we aimed to summarize effect size in terms of adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR), if that was not available, we considered the most adjusted model available.

Assessment of quality

Two independent authors assessed the quality of the included systematic reviews using the AMSTAR 2 tool [17]. For systematic reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, items 11, 12 and 15 were not considered. Also, small adaptations to some items were performed to make them more suitable to score (see the supplementary material). For an overall rating, we used the proposed scheme by Shea and colleagues that provides judgments of high, moderate, low or critically low confidence [17].

Results

Selection and inclusion of systematic reviews

The systematic search provided 46,284 record entries, reduced to 31,559 after deduplication. 939 records were selected for full text retrieval by screening titles and abstracts. Of these, nine were finally included after comparing full texts against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 reports the details of the study selection process.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews

Of the nine included reviews, five performed a meta-analysis on at least one of the outcomes of interest [18,19,20,21,22], while the remaining four were of a narrative nature [23,24,25,26]. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included reviews.

Systematic reviews with meta-analyses (MAs) generally had a search covering up to the first quarter of 2021. They included primary studies with mainly a cohort design, with the notable exceptions of the review by Liu and colleagues which considered case-series too and the review by Fond and colleagues which considered population-based cohort studies. MAs included a mean of 45 studies and a median of 21, the review by Liu and colleagues being an outlier with 149 included studies. Most of the MAs considered people with any mental disorder, possibly providing subgroups for specific disorders groups, while the review by Ceban and colleagues only focused on people with a mood disorder. Included studies covered a wide range of countries but with a general lack of representation from low- and middle-income countries. Infection by SARS-CoV-2 was defined by laboratory testing, ICD-10, electronic health records, or clinical judgment in the review by Ceban and colleagues and by laboratory results and diagnosis in conjunction with clinical presentation in the review by Liu and colleagues. Severe illness was defined as ICU admission, mechanical ventilatory support, oxygen therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and/or cardiopulmonary resuscitation by Ceban and colleagues and as hospitalization, ICU admission, or requirement for other special treatment (including oxygen therapy) by Liu and colleagues. For the review by Vai and colleagues, which does not have a “severe illness” outcome, we considered the outcome ‘hospitalisation’. For the review by Toubasi and colleagues, we considered the pooled mortality and severe illness outcome, as a separate estimate for mortality only was not available. Notably, no review was available to inform on the long-term physical symptoms after SARS-CoV2 infection. Four reviews reported estimates based on pooling adjusted ORs only [18, 19, 21, 22]. The review by Vai and colleagues reported a fully adjusted model only when considering people with any mental disorder, for the diagnostic groups we have then considered the ‘partially adjusted model’, where review authors considered aORs pooled together with crude ORs when an adjusted figure was not available from primary studies.

The four narrative reviews varied in their specific design, with two scoping reviews [25, 26], one rapid review [23], and one systematic review without meta-analysis [24]. They considered a wide range of study designs with the review by Lemieux and colleagues considering opinion pieces and other reviews; as for population of interest, they considered people with bipolar disorder [25], people with schizophrenia [24], people with mental illness in secure settings [23], and generally people with mental disorders [26].

Quality of included reviews

The AMSTAR 2 rated level of quality for all the MAs was “low”, with the exception of the review by Liu and colleagues with “high” and the review by Fond and colleagues with “critically low”. The review by Liu and colleagues did not have any weaknesses in critical items, while all other MAs did not report the list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion; the review by Fond and colleagues also did not account for the impact of risk of bias in primary studies on the results. The level of quality for the narrative reviews was “critically low” with the exception of the review by Fornaro and colleagues (“low”), mainly because of a lack of risk of bias assessment and protocol registration. See the supplementary material for detailed AMSTAR 2 evaluation of the included reviews.

Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Two MAs informed on the association between Sars-CoV-2 infection and having a pre-existing mental disorder compared to not having a pre-existing mental disorder (Fig. 2) [18, 19].

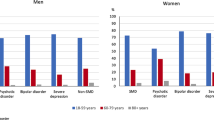

For people with any mental disorder, Liu and colleagues found a statistically significant positive association (OR: 1.71, 95% CI 1.09–2.69). For people with anxiety disorders, Liu 2021 and colleagues in a partially adjusted model found a statistically significant positive association although this effect size relies on two studies only (OR 1.63, 95%CI 1.44–1.85). For people with mood disorders, Liu 2021 and colleagues in a partially adjusted model found a statistically significant positive association (OR: 2.02, 95%CI 1.08–3.76), while Ceban and colleagues did not find a statistically significant association (OR: 1.50, 95%CI 0.75–2.99). For people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, Liu and colleagues, in a partially adjusted model, did not find a statistically significant association (OR: 1.72, 95%CI 0.62–4.77). The level of statistical heterogeneity was been generally very high, with most I2 statistics over 95%, with the exception of the estimate for people with mood disorders by Liu and colleagues (0%). I2 was not reported in Ceban et al., 2021.

Risk of severe illness

Three MAs informed on the association between a severe course of COVID-19 and having a pre-existing mental disorder compared to not having a pre-existing mental disorder (Fig. 3) [18,19,20].

For people with any mental disorder, both the review by Liu and colleagues and Vai and colleagues found a statistically significant positive association (OR: 1.32, 95%CI 1.19–1.46 and OR: 1.77, 95%CI 1.29–2.42, respectively). No study informed on people with anxiety disorders. For people with a mood disorder, Ceban and colleagues found no association (OR: 0.99, 95%CI: 0.80–1.24), Liu and colleagues in a partially adjusted model found a statistically significant positive association (OR: 1.34, 95%CI 1.08–1.67) while Vai and colleagues did not find a statistically significant association (OR 1.27, 95%CI 0.64–2.50). For people with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, both the reviews by Liu and colleagues and Vai and colleagues did not find a statistically significant association (OR: 1.22, 95%CI 0.70–2.13 and OR: 1.38, 95%CI 0.61–2.94, respectively). The level of statistical heterogeneity was moderate to very high, with an I2 statistic between 65 and 100%, but low for the estimate for people with mood disorders by Vai and colleagues (23%). I2 was not reported in Ceban et al., 2021.

COVID-19 related mortality

Four MAs informed on the association between mortality and having a pre-existing mental disorder compared to not having a pre-existing mental disorder (Fig. 4) [19,20,21,22].

For people with any mental disorder all four MAs found a statistically significant positive association, ranging from an OR of 1.38 (95%CI: 1.15–1.65) for the review by Fond and colleagues to 1.52 (95%CI: 1.20–1.93) for the review by Toubasi and colleagues (which however considered in this outcome severe illness cases as well). For people with anxiety disorders both the reviews by Liu and colleagues, in a partially adjusted model, and by Vai and colleagues did not find a statistically significant association (OR: 1.16, 95%CI 0.75–1.79 and OR: 1.01, 95%CI 0.77–1.32, respectively). For people with mood disorders, all three informing MAs found a statistically significant positive association with ORs ranging from 1.36 (95%CI: 1.15–1.79, Liu and colleagues, partially adjusted model) to 1.57 (95%CI: 1.26–1.95 Vai and colleagues). For people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders both the reviews by Liu and colleagues, in a partially adjusted model, and by Vai and colleagues found a positive association (OR 2.28, 95%CI 1.40–3.73, and OR 1.68, 95%CI 1.29–2.18, respectively). The level of statistical heterogeneity has been generally moderate to considerable, with an I2 statistic between 60% and 81.4%, but for the review by Vai and colleagues for the estimate for people with any mental disorder (39%), and low for the estimate for people with anxiety disorders (0%) and mood disorders (22%). The I2 has not been reported in Ceban et al., 2021.

Narrative reviews

The narrative reviews corroborated meta-analytic findings by indicating that patients with serious pre-COVID-19 mental disorders show adverse health outcomes related to COVID-19 infection in terms of higher severity and mortality. Fornaro and colleagues [25] performed a scoping review on clinical and public health themes for people with bipolar disorder. They identified four major themes from the 14 included papers, among which was the impact of having bipolar disorder on the risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 infection. For this theme, one study reported an increased risk of infection contraction for people with bipolar disorder [27]. This study was considered by the MAs previously reported. Karaoulanis and Christodoulou performed a systematic review without meta-analysis on infection rates and mortality in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The included studies suggest an increased infection and mortality risk; these studies have been included in the MAs previously reported. Lemieux and colleagues performed a rapid review on the management of COVID-19 for people with mental illness in secure settings. They considered a wide range of publications including opinion pieces and other reviews and report greater morbidity and mortality. Murphy and colleagues conducted a scoping review on the impact of COVID-19 and related restrictions on people with pre-existing mental disorders. They reported an increased infection risk in this population.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first umbrella review aimed at summarizing evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health outcomes in people with pre-existing mental disorders. Compared to the individual systematic reviews previously published, this umbrella review contextualizes the single piece of evidence, and provides an overview for different mental disorders, while systematic reviews have so far focused on specific diagnostic groups or considered only some of the outcomes of interest on the physical health repercussions of people with mental disorders. Two reviews considered several diagnostic groups and outcomes, however one employed only partially adjusted models within diagnostic groups [19], and the other could include a considerably smaller number of studies [20]. Overall, we found consistent results across the various reviews. Of interest, we found no previous reviews exploring the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Having any mental disorder was found to be associated with a higher likelihood of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 infection, a more severe COVID-19 illness, and higher mortality. We found different risks for different disorder groups. People with pre-existing anxiety disorders had an increased risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 infection; for people with mood disorders there was conflicting evidence of increased risk for severe COVID-19 course, and evidence of increased mortality; people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders had an increased risk of mortality, but there was no clear evidence of increased severe illness course for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Notably, we found no review assessing the association between long-term physical symptoms after COVID-19 and having a pre-existing mental disorder.

Having any mental disorder has been associated with an increased risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Looking at the data for the specific diagnostic groups, however, we observe that the association is confirmed for people with an anxiety disorder (and in an estimate based on only two studies) only, while for people with mood disorders the evidence is not consistent across reviews, and for people with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder the association is not statistically significant with a very wide confidence interval, making it hard to draw clear conclusions. Many people with a mental disorder live in shared households, nursing homes, therapeutic communities, or are inpatients. It has been noted that such settings pose challenges in putting into practice infection control measures [28]. In addition to that, people in an acute phase of a mental disorder might find it difficult to understand the need for and adhere to behavioural means of social distancing [29]. Still, these considerations regard mostly people with serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, adding difficulty to the interpretation of these results.

Having a mental disorder was associated with having a more severe illness course and increased mortality. This could be partially explained by the increased risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 infection, but as the three disorder groups showed differential patterns, we argue that additional factors may have influenced this outcome. In particular, anxiety disorders were not associated with increased mortality despite an increased infection risk, and indeed the results are compatible with a random distribution in terms of effect sizes and confidence intervals. Mood disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders have been associated with increased mortality from COVID-19 without conclusive evidence of increased infection risk. Several factors might come into play in determining such a negative outcome. People with severe mental illness, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, more frequently present with high BMI, diabetes mellitus, generally limited exercise tolerance, and are more likely to also smoke and have substance abuse disorders [6, 7, 30]. All of these are known risk factors for severe COVID-19 and for COVID-19 related mortality [2, 3, 31]. Although the use of adjusted odds ratios should have mitigated the impact of these risk factors in the estimate of effect sizes there was high heterogeneity in terms of adjusted factors used by primary studies. Therefore, it is possible that some factors, such as BMI, might not have been appropriately accounted for [32]. Many people with these disorders would have received an antipsychotic (and potentially benzodiazepines), with a possible negative impact on respiratory function [8]. However, there is limited evidence to support these hypotheses and future research is needed to fill this gap in knowledge. Moreover, we should take into consideration that socio-economic factors and stigma might have influenced the access to medical care of these persons [33]. Many primary studies were conducted during the initial phases of the pandemic when medical resources were scarce compared to needs, access to intensive care units was limited and subject to stringent triage, and no vaccine was available yet. The finding that for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders there was no increased risk for a more severe disease course, but higher risk for COVID-19 related mortality, is somewhat puzzling. The reviews have used slightly different definitions of “severe illness”, but all considered it as an operational composite outcome where many different events qualified, including oxygen therapy. Oxygen therapy has been a widespread need in COVID-19 patients, as arterial hypoxemia is a major feature of the disease [34]. It is possible that the definition of severe illness was therefore excessively sensitive and did not allow for the identification of differences between people with and without a pre-existing mental disorder. Another possible explanation is that people with schizophrenia might have been disproportionately affected by sudden death events. We know that cardiac sudden death events have been shown to be associated with COVID-19 [35] and that people with schizophrenia have a higher frequency of cardiovascular disease which may predispose to such events [36]. However, there is no direct evidence, and the use of adjusted estimates should have compensated for the increased cardiovascular burden. Overall, the mismatch between the risk of severe disease and mortality reinforces the need to better investigate factors associated with the increased mortality risk.

The findings of this umbrella review should be put into the context of some limitations. For the various diagnostic groups, the number of included primary studies has been limited, especially for anxiety disorders. Mood disorders include both depression and bipolar disorder, two disorders with different pharmacological approaches and neuro-inflammatory profiles. Additionally, information on the disease status of participants (remission or relapse) has generally not been considered. Low- and middle-income countries have been scarcely represented in the primary studies included by the reviews. The publication timeframe covered by the meta-analyses span to the first quarter of 2021; as such, these findings depict the first year of the pandemic. The general landscape has since changed, thanks to health care systems adaptations, improved COVID-19 treatments and importantly, the introduction of vaccines. There is, however, conflicting evidence regarding vaccine uptake rates in people with mental disorders, possibly due to regional differences [37, 38]. The reviews considered different study designs for inclusion; notably, Liu and colleagues considered case series. The review by Vai and colleagues informed on many diagnostic groups, but in only partially adjusted models. There has been considerable heterogeneity across all outcomes, which the meta-analyses struggled to explain. Heterogeneity likely reflects methodological and qualitative differences among the primary studies. Moreover, this high heterogeneity and the generally wide confidence intervals limit the accuracy of the estimates.

In light of these findings, there are relevant questions for future research. The new Omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads more easily but usually causes less severe illness [39]. Assessing if this holds true for people with a pre-exiting mental disorder as a risk factor would be valuable. In parallel, there is still limited evidence on vaccine hesitancy and uptake rate in this population. Moreover, the topic of long-term physical symptoms after COVID-19 in people with mental disorders remains scarcely investigated. Addressing these three points would allow for more effective health care planning and possibly targeted intervention to address vaccine hesitancy.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with pre-existing mental disorders more severely than people without in terms of physical health. People with pre-existing mental disorders, and especially those with mood or schizophrenia spectrum disorders, should have been considered at risk of severe course and increased mortality from COVID-19, similar to other identified risk groups such as patients with somatic health conditions.

Data availability

all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file and the original studies’ publications.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- MAs:

-

Meta-Analyses

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SR:

-

Systematic Review

References

Booth A, Reed AB, Ponzo S, Yassaee A, Aral M, Plans D, Labrique A, Mohan D. Population risk factors for severe disease and mortality in COVID-19: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0247461.

Singh AK, Gillies CL, Singh R, Singh A, Chudasama Y, Coles B, Seidu S, Zaccardi F, Davies MJ, Khunti K. Prevalence of co-morbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1915–24.

Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, Ba DM, Chinchilli VM. Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238215.

Lee SW, Yang JM, Moon SY, Yoo IK, Ha EK, Kim SY, Park UM, Choi S, Lee SH, Ahn YM, et al. Association between mental illness and COVID-19 susceptibility and clinical outcomes in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(12):1025–31.

Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):130–40.

Dickerson FB, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl JA, Fang L, Goldberg RW, Wohlheiter K, Dixon LB. Obesity among individuals with serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(4):306–13.

Suvisaari JM, Saarni SI, Perala J, Suvisaari JV, Harkanen T, Lonnqvist J, Reunanen A. Metabolic syndrome among persons with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in a general population survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1045–55.

Wang MT, Tsai CL, Lin CW, Yeh CB, Wang YH, Lin HL. Association between Antipsychotic Agents and Risk of Acute Respiratory failure in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):252–60.

Brandt J, Leong C. Benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs: an updated review of major adverse outcomes reported on in epidemiologic research. Drugs R D. 2017;17(4):493–507.

Mental Health. and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact: Scientific Brief [https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1]

Ioannidis JP. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ. 2009;181(8):488–93.

Solmi M, Correll CU, Carvalho AF, Ioannidis JPA. The role of meta-analyses and umbrella reviews in assessing the harms of psychotropic medications: beyond qualitative synthesis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(6):537–42.

Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(3):95–100.

COVID-19 and Mental Health. : An umbrella review of systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses [osf.io/jf4z2]

The EndNote Team. : EndNote. In., vol. EndNote 20. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Ceban F, Nogo D, Carvalho IP, Lee Y, Nasri F, Xiong J, Lui LMW, Subramaniapillai M, Gill H, Liu RN, et al. Association between Mood Disorders and Risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(10):1079–91.

Liu L, Ni SY, Yan W, Lu QD, Zhao YM, Xu YY, Mei H, Shi L, Yuan K, Han Y, et al. Mental and neurological disorders and risk of COVID-19 susceptibility, illness severity and mortality: a systematic review, meta-analysis and call for action. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101111.

Vai B, Mazza MG, Delli Colli C, Foiselle M, Allen B, Benedetti F, Borsini A, Casanova Dias M, Tamouza R, Leboyer M, et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(9):797–812.

Toubasi AA, AbuAnzeh RB, Tawileh HBA, Aldebei RH, Alryalat SAS. A meta-analysis: the mortality and severity of COVID-19 among patients with mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2021;299:113856.

Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, Loundou A, Goff DC, Lee SW, Lancon C, Auquier P, Baumstarck K, Llorca PM, et al. Association between Mental Health Disorders and Mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(11):1208–17.

Lemieux AJ, Dumais Michaud A-A, Damasse J, Morin-Major J-K, Nguyen TN, Lesage A, Crocker AG. Management of COVID-19 for persons with Mental Illness in Secure units: a Rapid International Review to inform practice in Québec. Victims & Offenders. 2020;15(7–8):1337–60.

Karaoulanis SE, Christodoulou NG. Do patients with schizophrenia have higher infection and mortality rates due to COVID-19? A systematic review. Psychiatriki. 2021;32(3):219–23.

Fornaro M, De Prisco M, Billeci M, Ermini E, Young AH, Lafer B, Soares JC, Vieta E, Quevedo J, de Bartolomeis A, et al. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with bipolar disorders: a scoping review. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:740–51.

Murphy L, Markey K, C OD, Moloney M, Doody O. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related restrictions on people with pre-existent mental health conditions: a scoping review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35(4):375–94.

Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):124–30.

de Girolamo G, Cerveri G, Clerici M, Monzani E, Spinogatti F, Starace F, Tura G, Vita A. Mental Health in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 emergency-the italian response. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):974–6.

Muruganandam P, Neelamegam S, Menon V, Alexander J, Chaturvedi SK. COVID-19 and severe Mental illness: impact on patients and its relation with their awareness about COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113265.

Hunt GE, Large MM, Cleary M, Lai HMX, Saunders JB. Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990–2017: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:234–58.

Wang QQ, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Volkow ND. COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1):30–9.

Luykx JJ, Lin BD. Are psychiatric disorders risk factors for COVID-19 susceptibility and severity? A two-sample, bidirectional, univariable, and multivariable mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):210.

Fond G, Pauly V, Leone M, Llorca PM, Orleans V, Loundou A, Lancon C, Auquier P, Baumstarck K, Boyer L. Disparities in Intensive Care Unit Admission and Mortality among patients with Schizophrenia and COVID-19: a National Cohort Study. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(3):624–34.

Tobin MJ. Basing Respiratory Management of COVID-19 on physiological principles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1319–20.

Tan Z, Huang S, Mei K, Liu M, Ma J, Jiang Y, Zhu W, Yu P, Liu X. The prevalence and Associated Death of Ventricular Arrhythmia and Sudden Cardiac death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:795750.

Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(5):317–33.

Mazereel V, Vanbrabant T, Desplenter F, Detraux J, De Picker L, Thys E, Popelier K, De Hert M. COVID-19 vaccination rates in a Cohort study of patients with Mental Illness in Residential and Community Care. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:805528.

Nilsson SF, Laursen TM, Osler M, Hjorthoj C, Benros ME, Ethelberg S, Molbak K, Nordentoft M. Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection among vulnerable and marginalised population groups in Denmark: a nationwide population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;16:100355.

Madhi SA, Kwatra G, Myers JE, Jassat W, Dhar N, Mukendi CK, Nana AJ, Blumberg L, Welch R, Ngorima-Mabhena N, et al. Population Immunity and Covid-19 severity with Omicron variant in South Africa. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1314–26.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the World Health Organization. The funding body The founding institution provided a list of research questions and methodological requirements, had no further role in protocol development and carrying on the review, including data collection, analysis, and interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ABW, PC, CB, MS, conceptualized the umbrella review design; all authors commented on the protocol; FB, SY, JLAM, MC, CC, ND, DF, MEG, CP, JvdW, SW performed the screening, data extraction and AMSTAR-2 assessment; all authors contributed to the interpretation of data; FB drafted the manuscript, CC submitted the manuscript, all authors revised the draft and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, policy, or views of WHO or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

not applicable.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertolini, F., Witteveen, A.B., Young, S. et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe COVID-19 illness and COVID-19 mortality in people with pre-existing mental disorders: an umbrella review. BMC Psychiatry 23, 181 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04641-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04641-y