Abstract

Background

Postnatal depression (PND) is a universal mental health problem that prevents mothers’ optimal existence and mothering. Although research has shown high PND prevalence rates in Africa, including Kenya, little research has been conducted to determine the contributing factors, especially in low-resource communities.

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the PND risk factors among mothers attending Lang’ata and Riruta Maternal and Child Health Clinics (MCH) in the slums, Nairobi.

Methods

This study was cross-sectional. It is part of a large study that investigated the effectiveness of a brief psychoeducational intervention on PND. Postnatal mothers (567) of 6-10 weeks postanatal formed the study population. Depression rate was measured using the original 1961 Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI). In addition, a sociodemographic questionnaire (SDQ) was used to collect hypothesized risk variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to explore predictors of PND.

Results

The overall prevalence of PND in the sample of women was 27.1%. Women aged 18-24 (β = 2.04 95% C.I.[0.02; 4.05], p = 0.047), dissatisfied with body image (β = 4.33 95% C.I.[2.26; 6.41], p < 0.001), had an unplanned pregnancy (β = 2.31 95% C.I.[0.81; 3.80], p = 0.003 and felt fatigued (β = − 1.85 95% C.I.[− 3.50; 0.20], p = 0.028) had higher odds of developing PND. Participants who had no stressful life events had significantly lower depression scores as compared to those who had stressful life events (β = − 1.71 95% C.I.[− 3.30; − 0.11], p = 0.036) when depression was treated as a continuous outcome. Sensitivity analysis showed that mothers who had secondary and tertiary level of education had 51 and 73% had lower likelihood of having depression as compared to those with a primary level of education (A.O.R = 0.49 95% C.I.[0.31-0.78], p = 0.002) and (A.O.R = 0.27 95% C.I.[0.09-0.75], p = 0.013) respectively.

Conclusion

This study reveals key predictors/risk factors for PND in low-income settings building upon the scanty data. Identifying risk factors for PND may help in devising focused preventive and treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Postnatal depression (PND) is a worldwide mental health problem [1] across countries and cultures [2]. The PND prevalence is higher (1.9% to 82.1%) in developing countries compared to (5.2% to 74.0%) in the developed countries [2]. In Africa, a systematic review and meta-analysis reported an overall pooled PND prevalence of 16.84% [3]. The few published research studies conducted in Kenya report high PND prevalence rates of 18.7% among mothers attending Mother and Child Health (MCH) clinics in urban, resource-poor environments [4], and 64.1% among mothers of children with severe acute malnutrition in general pediatric wards at Kenyatta national Hospitial [5].

Symptoms of PND include depressed mood, anxiety, anhedonia [6], fatigue [7], sleep difficulties [8] and concentration problems [8] which interfere with mothers’ parenting capacities [9]. The parenting incapacitation is associated with poor child’s physical health [10], and growth [11], and poor mother-child relationship [12]. These, in turn, lead to poor child’s developmental outcomes [13].

Postnatal depression is caused by many factors that may include: - psychosocial, socioeconomic, biological causes [14]. Some of the main psychosocial risk factors include; stressful life events [15], low income [16] and low education [17]. Besides, infant characteristics like adverse birth and infant health outcomes [3], difficult temperament [18], and unwanted gender [19] are risk factors. Mothers with poor physical health [20], poor obstetric histories [21], unplanned pregnancy [22], and a history of psychiatric illness [23] are likely to have PND. Moreover, poor environmental conditions [24] and cultural practices [25, 26] are also PND predictors.

Although PND is a public health problem, African countries [26], including Kenya, have neglected it considering the small number of published studies[18, 25]. Therefore, more research is needed in this area [3]. Moreover, it is crucial to investigate and understand PND risk factors in order to identify women at risk and offer them necessary intervention early enough [27]. This study aimed to investigate PND predictors in the early postnatal period (6-10 weeks) in two low-resourced urban communities. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper reporting prevalence and associated factors of depression postnatal mothers receiving MCH services in an urban slum setting in Kenya.

Methods, design, participants and procedures

This was cross-sectional study conducted within a large study that investigated the effectiveness of a brief psychoeducational intervention on PND in the slums, Nairobi [28]. Data were collected from Lang’ata and Riruta Health Centres- MCH clinics. Both are situated in Nairobi County and serve low-resource communities.

The sampling method for the main study within which the PND work was conducted is published in an earlier paper [28]. Briefly, a calculated sample of 227 participants would detect a difference of 15% in PND reduction with 90% power at 5% level of significance. To allow for 10% attrition rate, a minimum of 250 mothers were recruited in each of the groups, giving a total of 500 postnatal mothers. All the mothers in the main study were included in this study.

Mothers were recruited as they brought their infants for the first MCH clinic visit. Mothers were informed about the nature of the study and their rights by a Community Health Nurse Research assistant. Those who agreed to participate voluntarily signed a written consent form. Then they filled up a self-administered Social-Demographic Questionnaire (SDQ) and the original (1961) Becks Depression Inventory (BDI) which was in English and Kiswahili version. The variables are listed in Table 1. Of the total 591 eligible mothers, 575 participated in the study, which made a response rate of 97.3%. Sixteen participants refused to participate in the study.

All participants were over 18 years of age and gave informed consent before they were enrolled in the study. We obtained ethical approval from Kenyatta National Hospital Ethical Committee (Ref. KNH-ERC/A/311- 13th July 2015), Office of the President through the Ministry of Higher Education Science and Technology and Chief Administrative Officer (CHS) Nairobi County. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi - Ethics & Research Committee guidelines and regulations.

Data collection instruments

Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI)

The outcome of interest was depression, assessed using Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI). It was created by Dr. Aaron T. Beck and first published in 1961 [29]. Beck’s Depression Inventory is a self-administered report which takes approximately 10 min to complete and has demonstrated internal consistency yielding a mean coefficient alpha of 0.86 for psychiatric patients and 0.81 for non-psychiatric persons [30]. It is also positively correlated with the Hamilton Depression Scale [30] with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.71. The test was also found to have a high one-week test-retest reliability with a Pearson value of 0.93 [31]. BDI comprises 21 groups of statements describing the way one has been feeling during the past two weeks, including today. The response options range from 0 to 3, a value assigned to each answer to give the total score compared to a key to determine the severity of depression. A total score is calculated as the sum of the 21 items with a range of 0-63. The clinical cut-offs are 11-16 (mild mood disturbance), 17-20 (borderline clinical depression), 21-30 (moderate depression), 31-40 (severe depression), and 40-63 (extreme depression). The BDI has been successfully used in Kenya and other countries [32,33,34].

Sociodemographic questionnaire

A sociodemographic questionnaire was used to collect personal information and hypothesized PND risk factors that include: - mother’s age; educational level; marital status; monthly household income; suffering from chronic illness; satisfaction with body image; conflict with any close relatives; have a stressful life event; pregnancy planned; happy with infants’ health; not able to work (fatigue) and age of the infant and gestational age. The variables are listed in Table 1.

Data analysis

Item means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages were calculated for the sociodemographic, psychosocial related variables as well as for the depression scores. Crude association between each independent variable and the dependent variable (PND) was assessed using bivariate analyses. Variables with p-value < 0.25 for the crude association were entered into a multivariable generalized linear regression model to control the cofounders and identify independent predictors of PND. The p-value of < 0.25 was used in order not omit variables that might have an influence to the outcome variables but have been confounded by other variables. P-value of < 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance, and beta coefficients with a 95% confidence interval was used to indicate the strength of association. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using multivariable logistic regression between those with probable clinical depression (EPDS scores of ≥21) and those without depression ((EPDS scores of < 21). All analyses were conducted with IBM SPPS v 23.

Results

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the participants

Table 1 reports the characteristics of the participants in our sample. The mean age was 25.9 years and ranged from 18 to 40. The majority of the participants (45.1%) were aged between 18 and 24 years; 37.6% were aged between 25 and 30 years; 17.3% were aged between 30 and 40 years. The majority (89.8%) were married, more than half (53.4%) had secondary level of education, nearly 36.5% had a primary education level, the rest, (10.1%) had tertiary level of education. The majority (67.7%) of the participants were earning an income below 20,000 Kenya Shillings (about 196$) per month. 5.1% of the women had been suffering from chronic illness, 86.9% were satisfied with their body image, 11.6% had a conflict with their relatives, 28.4% had a stressful life event, 67.4% had planned their pregnancy, 66.7% were happy with the current baby’s health, and 23.8% had work-related problems (fatigue). The majority (70. 5%) had infants aged 7-10 weeks, while the rest had infants aged 6 weeks. About 9.3% had babies born before 37 weeks (pre-term births).

Prevalence of postnatal depression

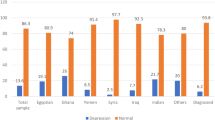

As presented in Fig. 1, PND scores based on the original (1961) Becks Depression Index (BDI0 cut-off points, were as follows: Normal (0-10), (n = 414, 73.0%); Mild mood disturbance (11-16); (n = 65, 11.5%); Borderline clinical depression (17-20); (n = 30, 5.3%); Moderate depression (21-30); (n = 42, 7.4%); Severe depression (31-40); (n = 10, 1.8%) and Extreme depression (40+); (n = 6, 1.1%). Therefore, the PND prevalence is 27.0%. The mean BDI score was 7.73, SD = 8.9 and range was 0-54.

Independent predictors of postnatal depression

As is shown in Table 2, after adjusting for all factors that were associated with postnatal depression at the bivariate level (p < 0.25) using generalized linear models, mothers who were younger (18-24 years) had significantly higher depression scores as compared to those who were older (31-40 years) (β = 2.04 95% C.I.[0.02; 4.05], p = 0.047). Mothers who were unsatisfied with their body image had significantly higher depression scores as those who were satisfied with their body image (β = 4.33 95% C.I.[2.26; 6.41], p < 0.001). Mothers who had no stressful life events had significantly lower depression scores compared to those who had stressful life events (β = − 1.71 95% C.I.[− 3.30; − 0.11], p = 0.036). Mothers who had an unplanned pregnancy had significantly higher depression scores than those who had a planned pregnancy (β = 2.31 95% C.I.[0.81; 3.80], p = 0.003). Mothers who did not report physical exhaustion (fatigue) had significantly lower depression scores as compared to those who did (β = − 1.85 95% C.I.[− 3.50; 0.20], p = 0.028).

Independent predictors of depression (sensitivity analysis results)

As shown in Table 3, after adjusting for all factors that were associated with postnatal depression at the bivariate level (p < 0.25) using generalized linear models. Mothers who had secondary and tertiary level of education had 51 and 73% lower likelihood of having depression as compared to those with primary level of education (A.O.R = 0.49 95% C.I.[0.31-0.78], p = 0.002) and (A.O.R = 0.27 95% C.I.[0.09-0.75], p = 0.013) respectively. Mothers who were satisfied with their body image had 63% lower likelihood of having depression as compared to those who were not (A.O.R = 0.37 95% C.I.[0.21-0.67], p = 0.001). Mothers who had conflicts with relatives were 2.37 times more likely to have depression as compared to those who don’t (A.O.R = 2.37 95% C.I.[1.28-4.28], p = 0.006). Mothers who had planned pregnancy had 50% lower likelihood of having depression as compared to those who had unplanned pregnancy (A.O.R = 0.50 95% C.I.[0.32-0.79], p = 0.003). Mothers who had work related problems were 2.11 times more likely to have depression as compared to those who didn’t (A.O.R = 2.11 95% C.I.[1.29-3.47], p = 0.003).

Discussion

The prevalence of PND was 27%. Published literature from Kenya shows high PND prevalence rates in different settings: 18.7% among women attending MCH clinics in two public hospitals in Nairobi [4] and 64.4% among mothers whose children were admitted to hospital due to severe acute malnutrition at Kenyatta National Hospital. The 27% PND prevalence rate is relatively lower than the reported 64.4% among women with babies with severe acute malnutrition [5], and higher than the 18.7% in mothers attending public hospitals. This indicate that the PND prevalence rate in this study is comparable but slightly higher than that of women attending the public hospitals which is expected since the mothers in this sample were exclusively from the slum settings and therefore extreme poverty. Recent research findings from other African countries show a high PND prevalence rates: Rwanda 63.6%, South Africa (57.14%) [35] and (38.8%) [36], Nigeria 35.6% [37]. Comparable to our finding, a systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a prevalence rate of 26% in Middle-East countries, while European countries had lower rates (8%) [38].

Regarding maternal age, younger mothers (18-24 years) had significantly higher depression scores than older (31-40 years) mothers. This is corroborated by other research findings [39,40,41,42]. The young mothers are usually inexperienced in taking up the challenging new maternal role [43], and therefore prone to maternal distress in several aspects including stress, adaptation, functioning and connecting [44]. Conversely, Smorti et al.’s study showed that older mothers are more likely to develop PND compared to young ones [27]. However, many other research studies have not found any association between maternal age and PND [45,46,47].

Women dissatisfied with their body image had a significant effect on the risk for developing PND symptoms in this study. Similar findings have been reported by Riquin et al. [48] and Hartley et al. [49]. Whereas most pregnancy and childbirth is naturally associated with weight gain due to the physiological changes involved, women are confronted with social pressures to maintain a pre-pregnant small size and shaped body in the postnatal period, contributing to their self-image perception [50, 51]. On the other hand, better body image is highly protective of developing PND [52]. In contrast, another research study showed that body image dissatisfaction was consistent but weakly associated with PND [53].

Participants who had no stressful life events had significantly lower depression scores than those who had stressful life events in this study. This suggests that negative life events are predictive of PND [54,55,56].

This study replicates the finding that unplanned pregnancy is a risk factor for PND, as other studies have shown [57, 58]. It is possible that the circumstances surrounding the unplanned pregnancy and the consequences resulting from having the pregnancy altogether amount to a stressful experience. For example, unplanned pregnancy has negative consequences that include; stigma, perceived loss of opportunities [59], poor health [60] and unhappiness [61].

Women who felt fatigued and unable to perform the usual household chores after giving birth were more depressed than those who did not. Correlating with our findings, several research studies have shown that that mothers in the high-risk depressive symptoms group were most likely to complain of fatigue [62,63,64]. It should be noted that depressive symptoms and physical fatigue overlap but have distinct trajectories [65, 66] and should be best understood as separate psychological constructs or experiences [67]. Research studies have recommended differentiating fatigue and depression for postnatal mothers [66, 68] to improve early postnatal care [65], which is a limitation in this study.

Sensitivity analysis was consistent with the main analysis, apart from mothers with secondary and tertiary levels of education, who were found to have a lower likelihood of having PND than those with a primary level of education. Therefore, this study suggests that high education may be a protective factor for PND, as other studies have shown [69, 70]. But Miyake et al. study found no association between maternal education and PND [71].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

-

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper reporting prevalence and associated factors of postnatal depression among mothers seeking services in an urban slum setting.

-

Depression was measured through face-to-face interviews using the original BDI questionnaire.

Limitations

-

Data on sociodemographic and lifestyle factors were collected using self-reports, which is prone to reporting bias.

-

In this study, fatigue was associated with PND although it can be understood as a separate construct.

This cross-sectional study cannot establish causal associations between postnatal depression and the risk factors examined. The generalizability of our findings is limited to settings that are similar to our study population. Future studies including larger and diverse populations are recommended.

Conclusion

This study builds upon the scant previous studies on PND from low-income countries. Identifying mothers at risk will lead to timely intervention, preventing PND and its progression.

Availability of data and materials

The availability of data for this manuscript is available upon formal request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- PND:

-

Postnatal Depression

- MCH:

-

Maternal and Child Health

- SDQ:

-

Sociodemographic Questionnaire

- BDI:

-

Beck’s Depression Inventory

- CHS:

-

Chief Administrative Officer

References

Almond P. Postnatal depression: a global public health perspective. Perspect Public Health. 2009;129(5):221–7.

Norhayati MN, Hazlina NN, Asrenee AR, Emilin WW. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:34–52.

Dadi AF, Akalu TY, Baraki AG, Wolde HF. Epidemiology of postnatal depression and its associated factors in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231940.

Ongeri L, Wanga V, Otieno P, Mbui J, Juma E, Vander Stoep A, et al. Demographic, psychosocial and clinical factors associated with postpartum depression in Kenyan women. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Haithar S, Kuria MW, Sheikh A, Kumar M, Vander SA. Maternal depression and child severe acute malnutrition: a case-control study from Kenya. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Putnam KT, Wilcox M, Robertson-Blackmore E, Sharkey K, et al. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):477–85.

Paul S, Corwin EJ. Identifying clusters from multidimensional symptom trajectories in postpartum women. Res Nurs Health. 2019;42(2):119–27.

Santos HP Jr, Kossakowski JJ, Schwartz TA, Beeber L, et al. Longitudinal network structure of depression symptoms and self-efficacy in low-income mothers. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191675.

Young KS, Parsons CE, Stein A, Kringelbach ML. Motion and emotion: depression reduces psychomotor performance and alters affective movements in caregiving interactions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:26.

Scorza P, Owusu-Agyei S, Asampong E, Wainberg ML. The expression of perinatal depression in rural Ghana. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2015;8(4):370–81.

Nguyen PH, Friedman J, Kak M, Menon P, Alderman H. Maternal depressive symptoms are negatively associated with child growth and development: evidence from rural India. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(4):e12621.

Nakano M, Upadhyaya S, Chudal R, Skokauskas N, Luntamo T, Sourander A, et al. Risk factors for impaired maternal bonding when infants are 3 months old: a longitudinal population based study from Japan. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women Health. 2019;15:1745506519844044.

Saleh ES, El-Bahei W, del El-Hadidy MA, Zayed A. Predictors of postpartum depression in a sample of Egyptian women. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:15.

Tebeka S, Le Strat Y, Mandelbrot L, Benachi A, et al. Early-and late-onset postpartum depression exhibit distinct associated factors: the IGEDEPP prospective cohort study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021.

Niyonsenga J, Mutabaruka J. Factors of postpartum depression among teen mothers in Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2020;1-5.

Decastro F, Hinojosa-Ayala N, Hernandez-Prado B. Risk and protective factors associated with postnatal depression in Mexican adolescents. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2011;32(4):210–7.

Tester-Jones M, O’Mahen H, Watkins E, Karl A. The impact of maternal characteristics, infant temperament and contextual factors on maternal responsiveness to infant. Infant Behav Dev. 2015;40:1–1.

Ye Z, Wang L, Yang T, Chen LZ, Wang T, et al. Gender of infant and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis based on cohort and case-control studies. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2020:1–10.

Kızılırmak A, Calpbinici P, Tabakan G, Kartal B. Correlation between postpartum depression and spousal support and factors affecting postpartum depression. Health Care Women Int. 2020;14:1–5.

Dekel S, Ein-Dor T, Berman Z, Barsoumian IS, Agarwal S, Pitman RK. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2019;22(6):817–24.

Upadhyay AK, Singh A, Singh A. Association between unintended births and risk of postpartum depression: evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. SSM-Popul Health. 2019;9:100495.

Underwood L, Waldie KE, D’Souza S, Peterson ER, Morton SM. A longitudinal study of pre-pregnancy and pregnancy risk factors associated with antenatal and postnatal symptoms of depression: evidence from growing up in New Zealand. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(4):915–31.

Azad R, Fahmi R, Shrestha S, Joshi H, Hasan M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression within one year after birth in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0215735.

Chee CY, Lee DT, Chong YS, Tan LK, et al. Confinement and other psychosocial factors in perinatal depression: a transcultural study in Singapore. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1-3):157–66.

Atuhaire C, Brennaman L, Cumber SN, Rukundo GZ, Nambozi G. The magnitude of postpartum depression among mothers in Africa: a literature review. Pan African Med J. 2020;37.

Smorti M, Ponti L, Pancetti F. A comprehensive analysis of post-partum depression risk factors: the role of socio-demographic, individual, relational, and delivery characteristics. Front Public Health. 2019;7:295.

Kariuki EW, Kuria MW, Were FN, Ndetei DM. Effectiveness of a brief psychoeducational intervention on postnatal depression in the slums, Nairobi: a longitudinal study. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2021;24(3):503–11.

Beck A, Ward C, Mendelsohn M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71 [31].

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100.

B. G. Beck AT, Steer RA, Beck depression inventory (BDI-II) 1996.

Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a persian-language version of the Beck depression inventory- second edition: BDI-II Persian. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21(4):185–92.

Ndetei DM, Khasakhala LI, Kuria MW, Mutiso VN, et al. The prevalence of mental disorders in adults in different level general medical facilities in Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):1–8.

Musyimi CW, Mutiso V, Nayak SS, Ndetei DM, et al. Quality of life of depressed and suicidal patients seeking services from traditional and faith healers in rural Kenya. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(95):1–10.

Mokwena K, Masike I. The need for universal screening for postnatal depression in South Africa: confirmation from a Sub-District in Pretoria, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):6980.

Omole OB, Phukuta NS. Prevalence and risk factors associated with postnatal depression in a south African primary care facility. African J Primary Health Care Family Med. 2020;12(1):1–6.

Adeyemo EO, Oluwole EO, Kanma-Okafor OJ, Izuka OM, Odeyemi KA. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among postnatal women in Lagos. Nigeria African Health Sci. 2020;20(4):1943–54.

Shorey S, Chee CY, Ng ED, Chan YH, San Tam WW, Chong YS. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;104:235–48.

Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, Harlow BL, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;60(3):221–7.

Saligheh M, Rooney RM, McNamara B, Kane RT. The relationship between postnatal depression, sociodemographic factors, levels of partner support, and levels of physical activity. Front Psychol. 2014;5:597.

Khalifa DS, Glavin K, Bjertness E, Lien L. Determinants of postnatal depression in Sudanese women at 3 months postpartum: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009443.

Agnafors S, Bladh M, Svedin CG, Sydsjö G. Mental health in young mothers, single mothers and their children. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–7.

Corkin MT, Peterson ER, Andrejic N, Waldie KE, et al. Predictors of mothers’ self-identified challenges in parenting infants: insights from a large, nationally diverse cohort. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(2):653–70.

Copeland DB, Harbaugh BL. “It's hard being a mama”: validation of the maternal distress concept in becoming a mother. J Perinat Educ. 2019;28(1):28–42.

Eastwood JG, Phung H, Barnett B. Postnatal depression and socio-demographic risk: factors associated with Edinburgh depression scale scores in a metropolitan area of New South Wales, Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiat. 2011;45(12):1040–6.

Silverman ME, Reichenberg A, Savitz DA, Cnattingius S, et al. The risk factors for postpartum depression: a population-based study. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(2):178–87.

Alharbi AA, Abdulghani HM. Risk factors associated with postpartum depression in the Saudi population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:311.

Riquin E, Lamas C, Nicolas I, Lebigre CD, et al. A key for perinatal depression early diagnosis: the body dissatisfaction. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:340–7.

Hartley E, Hill B, McPhie S, Skouteris H. The associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms, body image, and weight in the first year postpartum: a rapid systematic review. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2018;36(1):81–101.

Lovering ME, Rodgers RF, George JE, Franko DL. Exploring the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction in postpartum women. Body Image. 2018;24:44–54.

Rallis S, Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ. Predictors of body image during the first year postpartum: a prospective study. Women Health. 2007;45(1):87–104.

Han SY, Brewis AA, Wutich A. Body image mediates the depressive effects of weight gain in new mothers, particularly for women already obese: evidence from the Norwegian mother and child cohort study. BMC Public Health 2016;16(1):1-0.

Silveira ML, Ertel KA, Dole N, Chasan-Taber L. The role of body image in prenatal and postpartum depression: a critical review of the literature. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2015;18(3):409–21.

Nurbaeti I, Deoisres W, Hengudomsub P. Association between psychosocial factors and postpartum depression in South Jakarta. Indones Sex Reprod Healthcare. 2019;20:72–6.

Hamdan A, Tamim H. Psychosocial risk and protective factors for postpartum depression in the United Arab Emirates. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2011;14(2):125–33.

Guintivano J, Sullivan PF, Stuebe AM, Penders T, et al. Adverse life events, psychiatric history, and biological predictors of postpartum depression in an ethnically diverse sample of postpartum women. Psychol Med. 2018;48(7):1190.

Abebe A, Tesfaw G, Mulat H, Hibdye G. Postpartum depression and associated factors among mothers in Bahir Dar town. Northwest Ethiopia Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):1–8.

Jayaweera RT, Ngui FM, Hall KS, Gerdts C. Women’s experiences with unplanned pregnancy and abortion in Kenya: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191412.

Hall KS, Dalton VK, Zochowski M, Johnson TR, Harris LH. Stressful life events around the time of unplanned pregnancy and women’s health: exploratory findings from a national sample. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(6):1336–48.

Barton K, Redshaw M, Quigley MA, Carson C. Unplanned pregnancy and subsequent psychological distress in partnered women: a cross-sectional study of the role of relationship quality and wider social support. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–9.

Giallo R, Gartland D, Woolhouse H, Brown S. “I didn’t know it was possible to feel that tired”: exploring the complex bidirectional associations between maternal depressive symptoms and fatigue in a prospective pregnancy cohort study. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2016;19(1):25–34.

Bozoky I, Corwin EJ. Fatigue as a predictor of postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(4):436–43.

Corwin EJ, Brownstead J, Barton N, Heckard S, Morin K. The impact of fatigue on the development of postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(5):577–86.

Kuo SY, Yang YL, Kuo PC, Tseng CM, Tzeng YL. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and fatigue among postpartum women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(2):216–26.

Giallo R, Wade C, Cooklin A, Rose N. Assessment of maternal fatigue and depression in the postpartum period: support for two separate constructs. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2011;29(1):69–80.

Giallo R, Gartland D, Woolhouse H, Brown S. Differentiating maternal fatigue and depressive symptoms at six months and four years post partum: considerations for assessment, diagnosis and intervention. Midwifery. 2015;31(2):316–22.

Runquist JJ. A depressive symptoms responsiveness model for differentiating fatigue from depression in the postpartum period. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2007;10(6):267–75.

Fiala A, Švancara J, Klánová J, Kašpárek T. Sociodemographic and delivery risk factors for developing postpartum depression in a sample of 3233 mothers from the Czech ELSPAC study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–0.

Grussu P, Quatraro RM. Prevalence and risk factors for a high level of postnatal depression symptomatology in Italian women: a sample drawn from ante-natal classes. Europ Psychiatry. 2009;24(5):327–33.

Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Sasaki S, Hirota Y. Employment, income, and education and risk of postpartum depression: the Osaka maternal and child health study. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):133–7.

Qi W, Zhao F, Liu Y, Li Q, Hu J. Psychosocial risk factors for postpartum depression in Chinese women: a meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–5.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the women who voluntarily participated in the study. We also acknowledge the research assistants and the statistician who worked hard to make this work possible in their respective roles.

Funding

This work was self-funded within the PhD program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This paper is part of a PhD thesis undertaken by the lead author at the University of Nairobi. EWK wrote the manuscript. MWK, FNW and DMN contributed to intellectual feedback. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants enrolled in the study were over 18 years of age and gave informed consent. Approval was obtained from Kenyatta National Hospital Ethical Committee, Office of the President through the Ministry of Higher Education Science and Technology, the Chief Administrative Officer (CHS) Nairobi County. All eligible study participants were explained; the nature and purpose of the study, their rights, procedures, potential risks and benefits of participation before they gave consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kariuki, E.W., Kuria, M.W., Were, F.N. et al. Predictors of postnatal depression in the slums Nairobi, Kenya: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 22, 242 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03885-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03885-4