Abstract

Background

Negative self-perceptions is one of the most common symptoms of depression in young people, and has been found to be strongly associated with severity of depression symptoms. Psychological treatments for adolescent depression are only moderately effective. Understanding the role and importance of these self-perceptions may help to inform and improve treatments. The aim of this review was to examine self-evaluation as a characteristic of adolescent depression, and as an active ingredient in treatment for adolescent depression.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review which included quantitative and qualitative studies of any design that reported on self-evaluation as a characteristic of, or focus of treatment for, adolescent depression. Participants were required to be 11–24 years and experiencing elevated symptoms of depression or a diagnosis. We also met with 14 expert advisory groups of young people with lived experience, clinicians, and researchers, for their input. Findings from 46 peer-reviewed research studies are presented alongside views of 64 expert advisors, to identify what is known and what is missing in the literature.

Results

Three overarching topics were identified following the review and reflections from advisors: 1) What does it look like? 2) Where does it come from? and 3) How can we change it? The literature identified that young people view themselves more negatively and less positively when depressed, however expert advisors explained that view of self is complex and varies for each individual. Literature identified preliminary evidence of a bidirectional relationship between self-evaluation and depression, however, advisors raised questions regarding the influences and mechanisms involved, such as being influenced by the social environment, and by the cognitive capacity of the individual. Finally, there was a consensus from the literature and expert advisors that self-evaluation can improve across treatment. However, research literature was limited, with only 11 identified studies covering a diverse range of interventions and self-evaluation measures. Various barriers and facilitators to working on self-evaluation in treatment were highlighted by advisors, as well as suggestions for treatment approaches.

Conclusions

Findings indicate the importance of self-evaluation in adolescent depression, but highlight the need for more research on which treatments and treatment components are most effective in changing self-evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression markedly increases in adolescence [1], with 2.6% of young people experiencing depression at any one time [2], with a cumulative frequency of depression over the course of adolescence rising to as high as 20% by the age of 18 years [3]. The experience of depression in youth can have significant long-term implications [4], including further episodes of depression as an adult [5, 6], the development of other mental health disorders [7, 8] and an increased risk of suicidal behaviour [9]. Adolescent depression has also been associated with functional impairment across the life course such as educational underachievement, low income levels and unemployment [10].

Negative self-perceptions, including worthlessness, are one of the most common symptoms of depression in young people [11], as well as being a core component of the cognitive model of depression [12]. Beck proposed that depressed individuals view themselves, the world and the future in a negative way and that this ‘cognitive triad’ affects how they think, feel, and act, and consequently maintains their depression. In support of the cognitive model, results have shown that depressed adolescents characteristically use more negative and fewer positive words to describe themselves compared to healthy young people [13,14,15]. Furthermore, negative self-evaluation severity correlates with depression severity in community samples [16] and can identify depression diagnoses as accurately as a full depression symptom questionnaire [17].

Self-concept develops across the lifespan. During early childhood, children typically have inflated global self-esteem, with unrealistically positive domain specific self-concepts [18, 19]. As cognitive ability advances, global self-esteem decreases, as specific self-concepts are formed with influences from external feedback and social interactions [19, 20]. During adolescence, the evaluation of the ‘self’ becomes increasingly more complex. The ability to engage in abstract thinking allows for a more sophisticated sense of self to develop, incorporating social comparisons and different social roles [20, 21]. Most current research in the context of ‘self’ and adolescent depression has focused on global self-esteem, and little is known about the more specific and complex self-concepts, as well as the role of this developmental pathway to self-concept. Furthermore, even though this work is focused on the ‘self’, the literature drawing on young people’s voices, such as qualitative methods, is extremely lacking, although the studies that have been conducted do suggest that young people place significant importance on the subject even when it is not a direct target of the research [22, 23].

One key challenge with the ‘self’ literature is the diverse range of terminology. Three key terms commonly used are: self-efficacy – “a person’s judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances” [24]; self-esteem – an individual’s confidence in their worth or abilities [25]; and self-concept – a view constructed of one’s self, which is developed through experiences and evaluations adopted from others [25]. Many other terms are also used interchangeably. The present study reports on ‘self-evaluation’ with our working definition of ‘the perceptions and beliefs that a person holds about themselves, specifically the emotionally-valenced qualities, characteristics and traits (both positive and negative), and the person’s judgement of the value of these attributes’. This overlaps with ‘self-concept’ but is distinct from self-esteem (which refers to a more global view), and self-efficacy (which relates to the ability to produce certain actions or skills).

Current adolescent depression therapies are only moderately effective [26, 27], so understanding the role of self-evaluations may help to inform and improve treatments. This project was carried out as part of the Wellcome Trust Mental Health Priority Area, specifically their review of the “active ingredients” involved in treatment of anxiety and depression in young people. The “active ingredients” terminology draws on a cooking analogy of the key ingredients in a recipe, i.e. those needed for success, considering the individual receiving the treatment, the quantity and quality of the ingredients, and the cost and accessibility of these ingredients. Whilst there was emerging evidence of a key role for self-evaluation in depression from the quantitative literature, to the authors’ knowledge, there was no existing review of self-evaluation in adolescent depression, and the work that has been conducted has been hard to pull together due to the heterogenous terminology used in this field. Furthermore, given the growing recognition of an important role for lived experience input in research, it was decided that a scoping review, supported by consultation with expert advisors regarding the gaps in the literature, would provide the most comprehensive next step for advancing the knowledge regarding whether self-evaluation might be a key ‘active ingredient’ in the treatment of adolescent depression.

A scoping review, according to the PRISMA Guidelines - Extension for Scoping Reviews [28], follow a systematic approach to map evidence and identify main concepts. Scoping reviews can meet various objectives, but in the current case, a scoping review was deemed most appropriate as the authors wanted to establish the size, range and nature of evidence on self-evaluation in adolescent depression, and because the methodology of existing research is heterogenous. This scoping review can also establish the value of undertaking a future full systematic review.

We aimed to conduct a review to examine what is known about self-evaluation as 1) a characteristic of adolescent depression, and 2) an active ingredient in treatment for adolescent depression. This research takes a novel approach by integrating the scoping review with expert advisory input from young people with lived experience, clinicians, and researchers. The review reports on the views of the advisors and how their insights align with, or differ from, the existing literature. On this basis, the following research questions were formulated:

-

1)

What does existing research tell us about self-evaluation as a characteristic of adolescent depression, and as an active ingredient in treatment for adolescent depression?

-

2)

To what extent does the existing research reflect the lived experience of self-evaluation and depression, according to experts by experience?

Methods

Systematic literature search

The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews [28], and the 22-item checklist has been included as supplementary material. A PROSPERO registration form was utilised to help establish methodology although it was not able to be published on the website due to the scoping nature of the review. The protocol can also be found in supplementary material.

Search strategy

We searched five electronic databases (WebofScience, EMBASE, PsychINFO, Medline, The Cochrane Library) from inception to 17th July 2020. The search string was developed based on a preliminary search of WebofScience and scoping searches, and adapted based on suggestions from advisor events.

The following search terms were used: (self-evaluat* OR self-concept OR self-worth OR self-aware* OR self-inhibiting OR “view of self” OR self-assessment* OR “positive evaluation” OR “negative evaluation” OR “positive self” OR “negative self” OR self-reflect* OR self-description OR cognitive-evaluation OR “self-referential processing” OR self-criticism OR self-perception OR self-cognition OR “cognitions about the self” OR self-schema* OR self-image OR “sense of self” OR self-identity OR self-representation OR self-belief* OR self-efficacy OR self-hat* OR self-appraisal) AND (depress* OR MDD OR “low mood”) AND (adolescen* OR teen* OR youth* OR young OR student* OR child* OR pupil* OR juvenile* OR “emerging adult”).

Eligibility criteria

Both quantitative and qualitative studies of any design that reported on self-evaluation as a characteristic, or focus of treatment, were eligible. Participants were required to be 11–24 years old to reflect current views of adolescent and ‘young people’ age range [29], experiencing elevated symptoms of depression or a depression diagnosis. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1.

Study identification and data charting

The first 5% of titles and abstracts were double screened by FO and JW, and discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third independent reviewer (BG). The inclusion criteria were further operationalised, then titles and abstracts screened by one of the team members. Full text reviews were double rated by FO and JW independently, discrepancies discussed and resolved with two independent reviewers (BG, LP). Finally, data was double-extracted, independently by two reviewers (FO, JW), and cross-referenced for discrepancies. Forms were drawn up for data extraction, identifying: author, year, number of participants, % female, age, population, study design, intervention type, measure of depression, type of self that is examined e.g. self-concept/self-evaluation, the measure or tool used to examine self, and key findings. Extracted data was then checked for accuracy and clarity by a third reviewer (LP).

Expert advisory groups

To address research question two, expert advisors were sought, including young people with experience of low mood or depression, clinicians with experience of working with adolescents with depression, and researchers with relevant expertise. The purpose of the expert advisors was to inform whether the identified research reflected the experience of relevant ‘experts’ and to help identify any gaps in the literature. These consultations did not constitute primary research and as such ethical approval was not obtained to conduct this exploration.

Advisory group attendees

Expert advisory groups of young people with lived experience of depression (n = 25), clinicians working with adolescents with depression (n = 30), and child/adolescent mental health researchers with relevant expertise (n = 9), were recruited. Young people with lived experience were contacted via existing, established lived experience advisory groups in the UK. Communication was initiated via group leads, who shared the opportunity with their networks. Groups were informed that we were looking for young people aged 11–24, with experience of low mood or depression. Clinicians and researchers were contacted via existing networks, personal communications and social media. Table 2 outlines the number of events and attendees.

Procedure

Figure 1 outlines the procedure overview. Expert advisory meetings took place using virtual video conferencing, facilitated by members of the research team.

At the start of each meeting, the purpose of the project, and an explanation of the active ingredient, was provided. Given the complex nature of self-evaluation, and the lack of research specifically on self-evaluation as an active ingredient in improving depression outcomes, four main topics were discussed to help elicit expert views: 1) What is your understanding of self-evaluation? 2) How do young people describe / talk about themselves as part of assessment and treatment for adolescent depression? 3) Is self-evaluation currently targeted as part of treatment, and does self-evaluation change throughout treatment, even if not targeted? And 4) Should interventions more directly target self-evaluation, and if so, how should this be done?

After advisory events were completed and the systematic literature review was complete, integrated findings were shared with expert advisors and minor revisions made.

Data extraction and analysis

Advisory groups were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, read and re-read to ensure familiarity. Transcripts were reviewed by FO and JW, then interpretations and themes were compared and discussed. Themes were then taken to the remaining event facilitators for further discussion and consensus.

Strategy for synthesis of literature and expert advisor reflections

Scoping reviews aim to map key concepts, types of evidence and gaps in research related to a defined research topic by systematically searching, selecting and synthesising existing literature. To achieve these aims, our approach to data synthesis combines a descriptive quantitative summary of the extent of the literature with a narrative description of study findings. In line with published recommendations for scoping reviews [30, 31] and the requirements of the funder, the insights of stakeholders, including young people with lived-experience of depression, will be integrated with the narrative summary.

Results

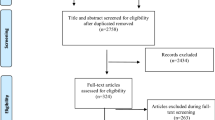

The study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 2. We identified 46 unique studies that met the inclusion criteria; characteristics and results of included studies are presented in Table 3.

Following data synthesis of the included studies and an examination of reflections from the expert advisors, answers to the two research questions (see below) were very broad:

-

1)

What does existing research tell us about self-evaluation as a characteristic of adolescent depression, and an active ingredient in treatment for adolescent depression?

-

2)

To what extent does the existing research reflect the lived experience of self-evaluation and depression, according to experts by experience?

For this reason, findings were grouped under three topic headings: 1) What does it look like? 2) Where does it come from? And 3) How can we change it? Findings from the scoping review are presented below in a narrative form, with an integration of reflections from the expert advisor reflections.

Topic One – What Does It Look Like?: “You Forget About All the Good Things, You’d Think, I’m Not Good at Anything” (YP)

The topic of ‘what does it look like?’ addresses self-evaluation as a characteristic of adolescent depression (RQ1), as well as how this aligns with advisor experiences (RQ2).

Thirty studies examined cross-sectional self-evaluation data in depressed samples, consistently reporting a critical view of self, and a reduced positive view. Although there was some evidence of a retained positive view of self, particularly in relation to prosocial traits such as being kind, trustworthy [45]. A number of studies found differences in the types of self-evaluation affected, reflecting the complexity of self-evaluation. For example, Dozois et al. [36] found that depressed adolescents demonstrated worse core beliefs of ‘disconnection’ (e.g. emotional inhibition, social isolation), ‘impaired autonomy’ (e.g. dependence, failure, dependence), and ‘impaired limits’ (e.g. insufficient self-control), but not for ‘exaggerated standards’ (e.g. self-sacrifice, unrelenting standards). Whereas, Koenig [40] found that depressed adolescents had lower self-image on ‘negative image’ (body and self image) and ‘introversion’ (social relationships), but not for ‘unmotivated’ (vocational and educational attitudes) and ‘maladjustment’ (self-reliance).

Expert advisory reflections

Consistent with the literature, there was agreement across advisors that both negative and positive self-evaluation are affected during depression. Young people used the terms: “useless”, “unimportant”, “all my fault”, “not good enough”, “doing everything wrong”, and highlighted an important role for negative evaluations of physical appearance, specifically weight, attractiveness, and acne. All groups also highlighted an overall lack of positive self-evaluation during depression; “I always see the weaknesses in myself, and I never really see the strengths” (young person), but in some cases, prosocial, positive self-evaluations remained, such as being “kind” or “helpful”, which is consistent with the findings from Orchard et al. [45]

All advisory groups emphasised the complex nature of self-evaluation, and that it varies across and between individuals. They raised how other comorbidities and chronic health issues can influence self-evaluation. Researchers discussed how self-evaluation is affected not only by content of thoughts, but also by their frequency and the value placed on different traits, “a lot of the young people I work with clinically, the extent to which they self-evaluate and the frequency, is often incredibly elevated relative to people who are not struggling with depression … it seems to be something to do with the frequency of self-evaluation as well as the content of it that becomes problematic” (researcher). The frequency or value of self-evaluative cognitions were not considered in any identified studies, suggesting a gap in the existing literature.

Young people highlighted the role of others in their self-evaluations, including worrying about how others view them, “I would worry that I was being boring or not funny, and I’d think that maybe they were just pitying me when they were being friends with me” (young person). They also described a scrutiny of ‘ideals’ and thinking that others are better. It was noted that societal comparisons are often biased by the young person’s own perception; “because I’ve never really had much input of what people actually think of me, it’s more me just doubting it and being scared that people think negative stuff of me, which backs up the negative things that I think about myself” (young person). Young people also discussed not wanting to bring others down, “[you] detach yourself from everything else because you don’t want those people to be impacted by the way you feel, and that’s why a lot of people hide it, because they don’t want it rubbing off on anyone else” (young person).

Topic Two – Where Does It Come From?: “I think it’s really hard to view things in isolation because everything, like your sense of yourself and outside events are impacting on you … they are so interlinked and interwoven” (young person)

The topic of ‘where does it come from?’ addresses how self-evaluation influences depression, and vice versa, as part of self-evaluation as a characteristic of adolescent depression (RQ1), as well as how this aligns with advisor experiences (RQ2). Five studies examined the prospective relationship between depression and self-evaluation. These indicated that elevated depression symptoms significantly increase risk of poor self-concept in the future [57, 58], and individuals with a poorer self-image were at increased risk of future depression [59,60,61], suggesting a possible bidirectional relationship.

Expert advisory reflections

The advisory groups discussed the mechanisms by which self-evaluation and depression are causally linked, which was a gap in the literature.

All advisory groups emphasised how self-evaluation is influenced by a wider context, including the social environment; “self-evaluation doesn’t exist in its own right within that individual, it seems to be shaped by individuals around us” (clinician). Young people described numerous social influences including bullies, social media, stereotypes, parents, and peer comparisons; “when bullying became a huge part of my life, that sort of just changed the way I viewed myself because I saw it as the truth” (young person). Young people also discussed how gender stereotypes and mental health stigma can cause negative self-evaluation, “When people talk about depressed people in a condescending way, describing them as “lazy” it feeds back into the cycle of negative self-talk” (young person). Relatedly, they discussed perceived judgment from families; “I wanted to talk about my feelings but I can’t really do that because my family would be mad” (young person), and “I’ve heard parents, grandparents, saying ‘you don’t want to be friends with them, they’ve got issues” (young person).

Young people also discussed the influence of cognitive cycles such as over-thinking and a lack of motivation; “you don’t have any motivation either so then you’re not as productive … Now in society your productivity kind of measures your worth, so if you’re not productive you don’t have any worth in a way” (young person), and behavioural cycles that can exaggerate the problem, such as self-neglect, “When you’re feeling low, it knocks your mental space into just attacking yourself, you care less about yourself and that’s what you need to do most” (young person).

Topic Three - How can we change it?: “I’m pretty sure everyone’s view of themselves could change if they’re getting better and if it doesn’t then I don’t think they’re getting better” (young person)

The topic of ‘how can we change it?’ reflects the effect of treatment for depression on self-evaluation, directly addressing self-evaluation as an active ingredient in treatment for adolescent depression (RQ1), as well as how this aligns with advisor experiences (RQ2). Eleven studies examined changes in self-evaluation across treatment for young people with depression. Ten of these examined pre- to post- measures of self-evaluation, using varying measurement tools. The remaining article was a case study describing the use of long-term psychodynamic therapy working with self-criticism amongst other difficulties [67].

All psychological intervention studies indicated improvements in self-evaluation for at least one of the interventions examined. However, findings relating to medication were mixed. One study examined medication compared to placebo and did not find an improvement in self-evaluation [68]. Another examined the combined effect of CBT with medication [65], and found that after 12 weeks, the combined treatment group outperformed all other groups on self-concept. Some studies reported between-group differences when comparing effects of different psychological interventions. Fine et al. [64] found a therapeutic support group evidenced greater improvements in self-concept compared to a social skills group post-treatment, but at 9 month follow up the social skills training group had caught up. Rosello et al. [73] found a greater improvement in self-concept for those who received CBT compared to Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT). One small, uncontrolled study reported that e-CBT showed improvements pre- to post-treatment, but face to face CBT did not [63].

In relation to domain-specific self-evaluation, two studies examined the effects on subscales: Hintikka et al. [66] found depressed young people showed improvements after treatment on psychological self-image but not familial self-image or all aspects of social self-image. King et al. [62] found that amongst hospitalized young people improvements were only seen in self-perception of social acceptance and global self-worth.

One intervention study reported that although depression severity improved across ages and treatment groups, younger participants showed greater improvements in self-concept [71]. This might suggest it is harder to shift self-evaluations in older participants perhaps due to a stabilising of self-concept. Furthermore, given depression improved in the waitlist control, it is possible that although depression can improve without direct intervention, to change self-concept, intervention is needed, particularly in older participants.

Expert advisory reflections

Key reflections that emerged included: the importance of addressing self-evaluation; directly vs indirectly targeting self-evaluation in treatment; and potential intervention approaches. Whilst not all of the reflections directly related to self-evaluation as an ‘active ingredient’, i.e. barriers and facilitators, they do highlight important areas for consideration in future work.

In line with the literature, young people agreed that view of self can change in treatment, describing “more confidence in self”, “more self-esteem”, “spending more time on self” and “acknowledging the positives within themselves”. Young people explained that self-evaluation should be targeted in treatment and that it is currently not targeted enough. They felt addressing it was important, because it is a “big part of depression”, and a possible “underlying factor”. They also expressed that not addressing self-evaluation could lead to harm itself, and that “seeing progress in self-evaluation can lead to a more optimistic outlook” for treatment. However, some young people raised concerns about it needing to be approached with caution.

Researchers and clinicians highlighted that change in self-evaluation could occur via implicit targeting as well as direct intervention, “[I] … would not talk to them about self-evaluation/esteem explicitly, but prompting questions are important in how they view themselves” (clinician). All groups suggested a number of potential treatment approaches for working with self-evaluation, these included: psycho-education, CBT, mindfulness, compassion-focussed therapy, ACT, value-based approaches, counselling, creative writing and antidepressants. In particular, all groups suggested that relationship focussed interventions e.g. IPT might be helpful. This contradicts findings from Rosello et al. [73], who found better results for CBT. Young people also highlighted that working on their sense of self might feel less pressured in an online format. Interestingly, this supports one study that found better effects for CBT in an online format [63].

Young people discussed the importance of an individualised approach, “Different techniques help different people so I think letting the person know they can express themselves in any way to help them like writing or drawing” (young person).

Barriers and facilitators

All advisory groups talked about barriers to working on self-evaluation in treatment. Researchers and clinicians highlighted that working with ‘self’ takes time and that most current treatments are short-term and self-evaluation is not a priority, “[there is a] real urgency to offer short term intervention, see people and get people through the door quickly so that we can protect our other services for people who are more unwell” (clinician). Researchers and clinicians discussed cognitive change over time and the ability to access and address thoughts about the self. They considered how “identity formation” is fluid during youth, potentially stabilising across adolescence. Young people also felt that a “deep-rooted” negative self-evaluation might be difficult to target. This aligns with findings from Rickhi et al. [71] where older participants showed less change in self-concept.

Young people highlighted additional barriers including limitations of using questionnaires to assess self-evaluation, as well as stigma and judgment, particularly from the therapist and family. They also discussed how certain therapist characteristics may make it difficult to discuss self-image, “I was saying that I thought I was fat one day, and then, because my therapist was quite a large lady, I would always think oh I’m being rude because obviously I’m a lot smaller than her” (young person).

Clinicians and young people talked about facilitators for working on self-evaluation in treatment. Clinicians highlighted “creating a non-judgemental space that they’re able to talk about stuff, whatever that stuff may be” (clinician), with feelings of safety and trust. Young people also noted some overlapping themes including good therapeutic alliance and trust, “Talking on a regular basis is the first step for treatment I think. When you talk a lot you develop a strong bond and then you open up more and learn that you won’t get judged and you can talk about whatever you want.” (young person).

Discussion

This methodologically novel review examined self-evaluation as a characteristic, and active ingredient in treatment, for adolescent depression. Specifically, research questions asked 1) What does existing research tell us about self-evaluation as a characteristic of adolescent depression, and as an active ingredient in treatment for adolescent depression? and 2) To what extent does the existing research reflect the lived experience of self-evaluation and depression, according to experts by experience? A scoping review was conducted and expert advisory groups (researchers, clinicians and young people with lived experience) consulted on their experiences of self-evaluation. The advisory views were integrated with findings from peer-reviewed journal articles, enabling potentially important gaps in the existing literature to be identified. This integrated approach identified three key self-evaluation topics that addressed both research questions simultaneously; ‘What does it look like?’, ‘Where does it come from?’ and ‘How can we change it?’

Summary of integrated findings

The expert advisors strongly believed that self-evaluation was a key component of depression for young people. Regarding ‘What does it look like?’ advisors agreed with the literature that young people view themselves more negatively and less positively when depressed, however advisors clarified that the view of self is complex and varies for each individual. For ‘Where does it come from?’, the literature examined a prospective relationship, with initial evidence of a bidirectional relationship between depression and self-evaluation. Advisors explored the mechanisms involved in this relationship relating to cognitive development (linking to broader literature on identity development [20, 21]), the social environment, and cognitive and behavioural negative cycles. Minimal literature on mechanisms was identified in our scoping review. Such work often begins with general population samples, where there are some emerging findings (e.g. using mood induction [74]). Future mechanistic research involving young people experiencing elevated depression is a key priority.

There was a consensus from the literature and expert advisors that self-evaluation can improve across treatment. However, research literature was limited, with only 11 identified studies covering a diverse range of interventions and self-evaluation measures.

Self-evaluation was rarely reported as an explicit treatment target, however, this does not necessarily mean that it has not been considered in therapy (e.g. in CBT, cognitive restructuring may be used to improve negative core beliefs about the self). It was clear from our advisors and literature that self-evaluation is covered in some theoretical models and intervention experiences, however, the advisors suggested that more direct emphasis on self-evaluation in treatment may be helpful. They also discussed various barriers and facilitators to working on self-evaluation, such as time, importance of trust, as well as suggestions for possible treatment approaches and techniques that might improve self-evaluation.

In the context of the wider literature

The findings of this review fit with the original cognitive model of depression which notes a key role for negative thoughts regarding the self [12], with consistent evidence of increased negative and decreased positive self-evaluations. Whilst it remains unclear whether there is a causal relationship between self-evaluation and depression, emerging evidence suggests there might be a bi-directional prospective association. Furthermore, although qualitative research is still substantially lacking in this area (with this review identifying only two qualitative studies), the reflections from the advisory groups supported the importance placed on self-evaluation in other research areas [23].

Whilst literature is yet to provide a strong developmental perspective to the relationship between depression and self-evaluation, e.g. whether the relationship changes over time. There is some evidence to suggest that adolescents at different ages may respond differently to intervention of self-evaluative thoughts, and this may fit with existing knowledge regarding the development and consolidation of a ‘sense of self’ [20].

Clinical and research implications

Although limited available evidence prevents firm treatment recommendations, our findings suggest that targeting self-evaluation as an active ingredient in treatment is likely to be complex. There appeared to be consensus that the experience and role of self-evaluation is unique and therefore interventions should be individualised. This was reflected in feedback from one young person advisor, who noted that self-evaluation was part of their assessment experience, but that “There needs to be a focus on allowing the young person to address what they think is the most important issue for themselves”. Exactly how self-evaluations are targeted for improvement as part of such interventions is unclear, inconsistent and requires further exploration. Further research is needed to understand the nature of self-evaluation and change throughout different types of therapy, to establish whether direct intervention is needed. As recognised by advisors, targeting self-evaluation should be done cautiously and collaboratively with the young person.

This scoping review and the advisory reflections highlight a number of areas for future research, in addition to next steps for intervention. The advisory groups described various experiences that had not been examined in the literature, for example, the importance of the frequency of the self-evaluations, and not just the content. This might reflect an experience of rumination, particularly with regards to self-evaluative thoughts. Rumination is robustly evidenced to be involved in the onset and maintenance of depression [75, 76], but is often considered to reflect broader negative thoughts. Adolescence is a time of critical development of self-concept with the theorised development of abstract self-portraits, internalised standards (i.e. self-generated expectations) and the integration of multiple selves into a unified self-concept [77]. As such, it may be that adolescents are particularly vulnerable to self-evaluative rumination. Future work would benefit from further examination of the frequency of negative self-evaluative thoughts, but it would also be interesting to examine whether this is unique to adolescents, or perhaps more prevalent amongst adolescents compared to adults.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first review to examine the broader literature under the umbrella term ‘self-evaluation’ in adolescent depression. The novel review strategy has some important strengths. Firstly, the inclusion of expert advisor input allows literature to be embedded in the real world, identifying richer and more diverse details about self-evaluation than those only described in published research studies. A traditional scoping review would rely on the author’s opinion regarding what important questions remain to be answered in this area. The methodology adopted here meant that the review could draw on a much wider range of expertise to make these judgements. Finally, the wide range of ‘self’ terms included in the systematic search allowed us to identify a diverse range of studies in this field. Whilst this presents challenges to the examination of literature in the field, e.g. the use of systematic approaches, initially pulling together these studies into one review will provide a useful first step for other reviews to follow. There are however some limitations to note. Studies in this review were required to include participants with a depression diagnosis or elevated symptom scores, so some studies with correlational and experimental designs were not included. Scoping reviews do not typically include a quality assessment of studies [78] or consideration of publication bias. Self-evaluation research is an emerging field and we hope this review will be a catalyst for many more studies on this important topic. However, due to the limited scope of the field, it was difficult to examine the role of self-evaluation as an ‘active ingredient’ in treatment as there were limited studies addressing this topic. This meant that the first research question was only partially answered. More primary research is needed examining whether improving self-evaluation improves outcomes for depression. Furthermore, future systematic reviews in the field will be needed and should include study quality and publication bias to help evaluate the evidence.

Conclusions

This novel scoping review identifies the importance and complexity of self-evaluation in adolescent depression, revealed by existing research and the views of expert advisors. Young people with depression experience impaired self-evaluation that can change over time, is complex in nature, and can improve with treatment. However, much more work is needed to understand the casual relationship between self-evaluation and depression in adolescence, improve and standardise self-evaluation measurement, and investigate the role of self-evaluation in treatment. We believe that to fully understand and improve outcomes for depressed adolescents, research needs to involve young people with lived experience as active stakeholders. We hope that this approach will continue to be embedded in future work.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):7–20. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/krmerikangas.

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381.

Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4.

Verboom CE, Sijtsema JJ, Verhulst FC, Penninx BW, Ormel J. Longitudinal associations between depressive problems, academic performance, and social functioning in adolescent boys and girls. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(1):247–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032547.

Dunn V, Goodyer IM. Longitudinal investigation into childhood-and adolescence-onset depression: psychiatric outcome in early adulthood. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(3):216–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.188.3.216.

Harrington R, Dubicka B. Natural history of mood disorders in children and adolescents. Depressed Child Adolesc. 2001;2:353–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511543821.014.

Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(3):225–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225.

Rudolph KD, Klein DN. Exploring depressive personality traits in youth: origins, correlates, and developmental consequences. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(4):1155–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990095.

Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3-4):372–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x.

Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(4):335–42. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036079.

Orchard F, Pass L, Marshall T, Reynolds S. Clinical characteristics of adolescents referred for treatment of depressive disorders. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2017;22(2):61–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12178.

Beck A, Alford BA. Depression: Causes and treatment. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

Auerbach RP, Stanton CH, Proudfit GH, Pizzagalli DA. Self-referential processing in depressed adolescents: a high-density event-related potential study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124(2):233–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000023.

Kelvin RG, Goodyer IM, Teasdale JD, Brechin D. Latent negative self-schema and high emotionality in well adolescents at risk for psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1999;40(6):959–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00513.

Timbremont B, Braet C, Bosmans G, Van Vlierberghe L. Cognitive biases in depressed and non-depressed referred youth. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15(5):329–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.579.

Hards E, Ellis J, Fisk J, Reynolds S. Negative view of the self and symptoms of depression in adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2020;262:143–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.012.

Orchard F, Reynolds S. The combined influence of cognitions in adolescent depression: biases of interpretation, self-evaluation, and memory. Br J Clin Psychol. 2018;57(4):420–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12184.

Pullmann H, Allik J, Realo A. Global self-esteem across the life span: a cross-sectional comparison between representative and self-selected internet samples. Exp Aging Res. 2009;35(1):20–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610730802544708.

Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH. Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14(3):158–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00353.x.

Harter S. Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence; 2012.

Sebastian C, Burnett S, Blakemore S-J. Development of the self-concept during adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(11):441–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.008.

Morey-Nase C, Phillips LJ, Bryce S, Hetrick S, Wright AL, Caruana E, et al. Subjective experiences of neurocognitive functioning in young people with major depression. BMC psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2197-1.

Weitkamp K, Klein E, Midgley N. The experience of depression: a qualitative study of adolescents with depression entering psychotherapy. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2016;3:2333393616649548. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393616649548.

Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1986;4(3):359–73. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359.

Liebert RM, Spiegler MD. Personality: Strategies and issues. Pacific Grove: Cole Publishing; 1990.

Goodyer IM, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy versus brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depression (IMPACT): a multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Asses (Winchester, England). 2017;21:1.

Eckshtain D, Kuppens S, Ugueto A, Ng MY, Vaughn-Coaxum R, Corteselli K, et al. Meta-analysis: 13-year follow-up of psychotherapy effects on youth depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(1):45–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.002.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Becker-Weidman EG, Reinecke MA, Jacobs RH, Martinovich Z, Silva SG, March JS. Predictors of hopelessness among clinically depressed youth. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(03):267–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465809005207.

Bennett DS, Ambrosini PJ, Bianchi M, Barnett D, Metz C, Rabinovich H. Relationship of Beck depression inventory factors to depression among adolescents. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(3):127–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00045-1.

Bradley KA, et al. Neural correlates of self-perceptions in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016;19:87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.02.007.

Cooper MJ, Rose KS, Turner H. Core beliefs and the presence or absence of eating disorder symptoms and depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(1):60–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20157.

Dozois DJ, Eichstedt JA, Collins KA, Phoenix E, Harris K. Core beliefs, self-perception, and cognitive organization in depressed adolescents. Int J Cogn Ther. 2012;5(1):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2012.5.1.99.

Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Fehon DC, Lipschitz DS, Martino S, McGlashan TH. Correlates of suicide risk in adolescent inpatients who report a history of childhood abuse. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):422–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-440X(99)90085-8.

Le Heath N, Brown AE. Self-concept differentiation and depressive symptomatology in children. Int J Psychol. 1999;34(2):95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075999399990.

Kendall PC, Stark KD, Adam T. Cognitive deficit or cognitive distortion in childhood depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1990;18(3):255–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00916564.

Koenig LJ. Self-image of emotionally disturbed adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1988;16(1):111–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00910505.

Korhonen V, Laukkanen E, Peiponen S, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Effect of major depression on the self-image of adolescent boys and girls. J Youth Adolesc. 2001;30(6):697–706. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012229611954.

Lopez Molina MA, Jansen K, Drews C, Pinheiro R, Silva R, Souza L. Major depressive disorder symptoms in male and female young adults. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(2):136–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2013.793369.

McClure E, Rogeness GA, Thompson NM. Characteristics of adolescent girls with depressive symptoms in a so-called" normal" sample. J Affect Disord. 1997;42(2-3):187–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(96)01412-7.

Ofonedu ME, Percy WH, Harris-Britt A, Belcher HM. Depression in inner city African American youth: a phenomenological study. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22(1):96–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9583-3.

Orchard F, Pass L, Reynolds S. ‘I am worthless and kind’; the specificity of positive and negative self-evaluation in adolescent depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2019;58(3):260–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12215.

Pilecki M, Józefik B. Self-image of girls with different subtypes of eating disorders. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2008;3:17–22.

Pinto A, Grapentine WL, Francis G, Picariello CM. Borderline personality disorder in adolescents: affective and cognitive features. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(10):1338–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199610000-00021.

Qian M, Wang A, Chen Z. A comparison of classmate and self-evaluation of dysphoric and nondysphoric Chinese students. Cognit Emot. 2002;16(4):565–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000329.

Quevedo K, Ng R, Scott H, Smyda G, Pfeifer JH, Malone S. The neurobiology of self-processing in abused depressed adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29(3):1057–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416001024.

Robinson KE, Jenson JM, Yaffe J. Depression and conduct disorder among hospitalized adolescents. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 1992;9(4):329–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00757088.

Ross M, Self-Schematic J. Instability in mild depression. J Soc Behav Pers. 1989;4:119.

Ross MJ, Mueller JH, De La Torre M. Depression and trait distinctiveness in the self-schema. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1986;4(1):46–59. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.1.46.

Rotundo N, Hensley V. The Children's depression scale. A study of its validity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1985;26(6):917–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb00606.x.

Savilahti EM, Haravuori H, Rytilä-Manninen M, Lindberg N, Kettunen K, Marttunen M. High Beck depression inventory 21 scores in adolescents without depression are associated with negative self-image and immature defense style. Psychiatry Res. 2018;263:61–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.040.

Wixom J, Ludolph P, Westen D. The quality of depression in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(6):1172–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199311000-00009.

Woo BS, et al. Development and validation of a depression scale for Asian adolescents. J Adolesc. 2004;27(6):677–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.12.004.

Ames ME, Leadbeater BJ. Depressive symptom trajectories and physical health: persistence of problems from adolescence to young adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:121–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.001.

Carbonell DM, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM. Risk and resilience in late adolescence. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 1998;15(4):251–72. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025107827111.

Ferro MA, Gorter JW, Boyle MH. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in Canadian emerging adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2322–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302817.

Fine S, Haley G, Gilbert M, Forth A. Self-image as a predictor of outcome in adolescent major depressive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34(8):1399–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb02098.x.

Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH, Bean J, Tamer R, Kraemer HC, Dohm FA, et al. Psychosocial and health consequences of adolescent depression in black and white young adult women. Health Psychol. 2005;24(6):586–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.586.

King CA, Naylor MW, Segal HG, Evans T, Shain BN. Global self-worth, specific self-perceptions of competence, and depression in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(4):745–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199307000-00007.

Alavi N, Stefanoff M, Hirji A, Khalid-Khan S. Cognitive Behavioural therapy through PowerPoint: efficacy in an adolescent clinical population with depression and anxiety. Int J Pediatr. 2018;2018:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1396216.

Fine S, Forth A, Gilbert M, Haley G. Group therapy for adolescent depressive disorder: a comparison of social skills and therapeutic support. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(1):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199101000-00012.

Gottlieb L, Martinovich Z, Meyers KM, Reinecke MA. Treatment for depression enhances protection: findings from the treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS). Int J Cogn Ther. 2016;9(1):38–56. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct_2016_09_02.

Hintikka U, Viinamäki H, Pelkonen M, Hintikka J, Laukkanen E, Korhonen V, et al. Clinical recovery in cognitive functioning and Self-image among adolescents with major depressive disorder and conduct disorder during psychiatric inpatient care. Am J Orthop. 2003;73(2):212–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.73.2.212.

Kurdziel G, Flores LY, Macfie J. The role of sexual and gender identity in long-term psychodynamic therapy for comorbid social anxiety and depression in an adolescent female. Clin Case Stud. 2018;17(5):311–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650118788668.

Le Noury J, Nardo J M, Healy D, Jureidini J, Raven M, Tufanaru C, et al. Restoring Study 329: efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence. BMJ. 2015;351:h4320. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4320.

Lusk P, Melnyk BM. The brief cognitive-behavioral COPE intervention for depressed adolescents: outcomes and feasibility of delivery in 30-minute outpatient visits. J Am Psychiatric Nurs Assoc. 2011;17(3):226–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390311404067.

Nasstasia Y, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Halpin SA, Hides L, Kelly BJ, et al. Differential treatment effects of an integrated motivational interviewing and exercise intervention on depressive symptom profiles and associated factors: a randomised controlled cross-over trial among youth with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:413–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.035.

Rickhi B, Kania-Richmond A, Moritz S, Cohen J, Paccagnan P, Dennis C, et al. Evaluation of a spirituality informed e-mental health tool as an intervention for major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults–a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0968-x.

Riley K. Effects of a collaborative outpatient therapy program on self-concept of adolescents with depression. Ther Recreat J. 2011;45:32–46.

Rosselló J, Bernal G, Rivera-Medina C. Individual and group CBT and IPT for Puerto Rican adolescents with depressive symptoms. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2008;14(3):234–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.234.

Hayden EP, Olino TM, Bufferd SJ, Miller A, Dougherty LR, Sheikh HI, et al. The serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region and brain-derived neurotrophic factor valine to methionine at position 66 polymorphisms and maternal history of depression: associations with cognitive vulnerability to depression in childhood. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(3):587–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000035.

Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(3):504–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x.

Harter S. Processes underlying adolescent self-concept formation; 1990.

Peters, M. et al. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers' manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the young people, clinician and researcher expert advisors who guided this research, and Chloe Gathercole, Molly Cross and Ipek Topbas for their help with title and abstract screening.

Methodology

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding

This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Mental Health Priority Area ‘Active Ingredients’ commission awarded to FO at University of Reading. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and advisors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Wellcome Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in screening abstracts and running advisory group events (FO, JW, BG, TC, SA, LP). FO, JW, BG and LP were involved in full-text review and data extraction. Transcription of events was conducted by JW and transcripts were reviewed by FO. Themes from literature and advisors were discussed by all authors (FO, JW, BG, TC, SA, LP). FO and JW drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in editing the manuscript (FO, JW, BG, TC, SA, LP). The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not needed for the reflections within this review. It should not be read as original research. All advisors voluntarily offered to take part in advisory events after being informed about the project.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Orchard, F., Westbrook, J., Gee, B. et al. Self-evaluation as an active ingredient in the experience and treatment of adolescent depression; an integrated scoping review with expert advisory input. BMC Psychiatry 21, 603 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03585-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03585-5