Abstract

Objective

It is estimated that up to 75% of patients with severe mental illness (SMI) also have substance use disorder (SUD). The aim of this systematic review was to explore the scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and/or substance abuse in relation to diagnosis and treatment of co-existing disorders and considerations for wider social and contextual factors in treatment recommendations.

Method

A protocol (PROSPERO CRD42020187094) driven systematic review was conducted. A systematic search was undertaken using six databases including MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, PsychInfo from 2010 till June 2020; and webpages of guideline bodies and professional societies. Guideline quality was assessed based on ‘Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II’ (AGREE II) tool. Data was extracted using a pre-piloted structured data extraction form and synthesized narratively. Reporting was based on PRISMA guideline.

Result

A total of 12,644 records were identified. Of these, 21 guidelines were included in this review. Three of the included guidelines were related to coexisting disorders, 11 related to SMI, and 7 guidelines were related to SUD. Seven (out of 18) single disorder guidelines did not adequately recommend the importance of diagnosis or treatment of concurrent disorders despite their high co-prevalence. The majority of the guidelines (n = 15) lacked recommendations for medicines optimisation in accordance with concurrent disorders (SMI or SUD) such as in the context of drug interactions. Social cause and consequence of dual diagnosis such as homelessness and safeguarding and associated referral pathways were sparsely mentioned.

Conclusion

Despite very high co-prevalence, clinical guidelines for SUD or SMI tend to have limited considerations for coexisting disorders in diagnosis, treatment and management. There is a need to improve the scope, quality and inclusivity of guidelines to offer person-centred and integrated care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is estimated that up to 75% of patients with severe mental illness (SMI) also have substance use disorder (SUD) and about 60% of adults with SUD have at least one type of SMI [1,2,3,4], with one being either the cause or consequence of the other or various social issues leading to both issues at the same time [5, 6]. Genetic factors for such co-morbidity including variations in how people respond to treatments have also been suggested [7]. Coexisting disorders can result in greater incidence of adverse health outcomes, suicide, unplanned hospital admissions [2, 8,9,10] and early mortality [11,12,13]. Social consequences include violence, homelessness, involvement with criminal justice system, and relationship breakdowns have also been suggested [14,15,16,17]. For example, between a quarter and a third of prison populations in the Western countries are known to have a dual diagnosis [15, 18]. Involvement with criminal justice system is also known to adversely impact patient access to SMI and SUD services [19].

Assessment and treatment of patients in regard to dual diagnosis presents a challenge for care providers. Care providers can face challenges in managing psychiatric symptoms, substance craving, and social issues as a result of coexisting disorders [20]. In addition, fragmentation of care, for example, physical separation of services can result in barrier to access and provision of care [21,22,23]. Different opinion and divergent views of health care providers about treatment plan are also other known challenges [24, 25]. Parallel and separate care provided for each disorder within the same or different healthcare settings for patients with coexisting disorders are likely to be ineffective. This can lead to fragmentation of care, lack of timely access to treatment, withdrawal from treatment, physical multi-morbidity, and early deaths [9, 26, 27]. The advantage of considering both disorders together is that both SMI and SUD are simultaneously addressed and are given due attention [28]. However, practices are often patchy. Despite the known effectiveness of integrated treatment models for patients with coexisting disorders, integrated services availability remains sparse. A study conducted in the United States sampled programs from all over the US and showed that only 18% of addiction treatment and 9% of mental health programs had sufficient capacity to provide simultaneous services for patients with coexisting disorder [29].

A previous systematic review published in 2010 evaluated SMI and SUD guidelines to investigate whether or not they addressed co-occurring disorders [30]. The review considered guidelines published until 2007 and was limited to the inclusion of guidelines published in the National Guideline Clearinghouse database. Guidelines developed by the professional societies and clinical excellence committees are important decision tools that guide health care professionals’ care of their patients. Evidence-based guidelines allow practitioners to follow the best available evidence and also speeds up the adaptation of new treatment approaches. While practitioners may utilize professional judgements and conduct their own evidence search to inform person-centred care, guidelines are cornerstones in healthcare practice and adherence to clinical guidelines is often taken synonymous to evidence based practice [31]. The aim of this systematic review was to explore the scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and/or substance abuse in relation to diagnosis and treatment of such co-existing disorders and consideration of wider social and contextual issues in treatment recommendations.

Methodology

Protocol and registration

The study protocol registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020187094). The review was conducted as per PRISMA checklist and statement [32] (Electronic supplementary material 1).

Criteria for considering guidelines for this review

The research for this review focused international guidelines which related to the assessment and treatment of either SUD, SMI or on concurrent disorders. The search was limited to guidelines published from 2010 until June 2020. To make sure that included guidelines represented current practice, guidelines published before 2010 were not considered. The search was restricted to guidelines published in the English language.

Search and selection of guidelines

The research for guidelines was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and PsychInfo, Google, Google scholar, Guideline Central; and national clinical guidelines and professional organizations’ web pages including National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) .

The search terms used related to SUD and SMI MeSH terms (electronic supplemental material 2). The screening process was performed in three distinct stages including title, summary or abstract and full texts. The selection of guidelines done independently by two reviewers (RA and VP) and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We searched reference list of included guidelines to identify any further guidelines.

Search definitions

We considered the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) definition of, ‘substance use disorder’ which is a single term combines both abuse and dependence [33]. Such substances include legal drugs such as alcohol, illicit drugs such as heroin and cocaine, and prescription drugs such as oxycodone [34]. The SMIs considered in this review were psychosis and other associated types of schizophrenia, as well as bipolar disorder. The terms coexisting disorder, co-occurring disorder, or dual diagnosis are frequently used to describe the existence of both conditions of SMI and SUD simultaneously.

Data extraction

After identification of eligible guidelines, data were extracted using a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet. Data were extracted in relation to guideline characteristics, targeted patient population and health care providers, screening and management of co-existing disorders including recommendations for treatment adjustments and consideration of monitoring of physical health or drug interactions. Consideration of offending behavior, risks of homelessness, violence, and suicide were also extracted. Data extraction was done by two authors (RA and VP) in duplicate and independently and any disagreements were resolved by further discussion.

Quality assessment

The included guidelines are appraised by using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool. The assessment of each guideline is carried out by following the users’ instruction manual for AGREE II instruments [35]. The assessment for the following domains: ‘scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence’ [36]. Each of the 23 items is scored 1 to 7 where 1 signals strong disagreement and 7 signals strong agreement and the final score is rated from 0 to 100%. In addition, there are two overall assessments of each guideline. The first one reflects the overall quality of each guideline. The second overall assessment allows assessment of whether or not the guideline is recommended for application in practice. Three distinct choices; namely, ‘Yes’, ‘Yes with modification’, or ‘No’ are utilized in relation to recommendation for use. Score sheet is demonstrated in Electronic supplemental material 3. Two reviewers independently assessed the included guidelines.

In order to calculate domain rate, the following equation from AGREE II users’ manual was used:

The rate of each domain = (total score of all items within the domain − lowest score of all items within the domain) / (highest score of all items within the domain − lowest score of all items within the domain) × 100.

A narrative synthesis was used to present the findings. Comparisons between guidelines are pre-identified in accordance with the particular objectives of the review.

Results

The search and selection of guidelines

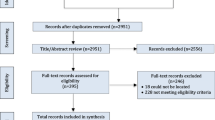

In total, 12,644 records were identified through the searching of various databases. After the exclusion of data de-duplication and both title and abstract screening, 32 guidelines were screened for eligibility. Twenty-one guidelines were included in this study (Fig. 1).

General characteristics of the included guidelines

Of the 21 included, three guidelines related to coexisting disorders [37,38,39], seven guidelines related to SUD including alcohol use disorder and opioid disorder (Table 1) [40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Eleven guidelines related to SMI (six of them were related to schizophrenia, and five of them were related to bipolar disorder) [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. The aim of each guideline is illustrated in Table 1.

Most of the included guidelines were produced by NICE in England (n = 5), followed by guidelines produced by British Association of Psychopharmacology in the UK (n = 3). Two of the included guidelines were published by APA in the USA, two of them were produced by the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) which developed by a group of experts from different countries, and nine guidelines were published by government departments of health [39, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 53, 54, 57] (Table 1).

Quality assessment of guidelines

The scores of each guideline against the criteria of the AGREE II tool are displayed in Table 2. In terms of ‘scope and purpose’, first domain had the highest domain score. Only four guidelines scored below 80% [39, 46, 54, 57] (Table 2). In the second domain, ‘stakeholder involvement’, the guidelines that were developed by NICE and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) demonstrated the highest score; 84 and 83%, respectively [37, 38, 44, 47, 48, 55] (Table 2). The ‘Rigour of development’ domain scores were generally low (Fig. 2). Fifteen out of 21 included guidelines rated below 70% (Table 2). Most of the guidelines scored higher in ‘Clarity of presentation’ domain (Fig. 2). The guidelines that were developed by NICE and SIGN obtained the highest scores [37, 38, 44, 47, 48, 55] (Table 2). Figure 2 shows that the ‘Applicability’ domain has the lowest domain score. Fifteen guidelines were graded below 50% (Table 2). With regard to the ‘Editorial independence’ domain, the highest score was reported with the NICE guidelines, this being 83%. The rest of the included guidelines were graded below 80% (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Assessment of concurrent problems

All of the included coexisting disorders guidelines emphasized that a comprehensive assessment should be carried out for patients with either SMI or SUD for dual diagnosis [37,38,39]. However, five out of eleven (45%) SMI guidelines did not highlight the assessment of coexisting disorders [47, 48, 54, 55, 57]. In addition, one SUD guidelines (14%) did not highlight the assessment of coexisting disorders [41] (Table 3).

Three guidelines explicitly stated that patients with SMI with coexisting SUD who completed their SMI treatment course should stay in the hospital to avoid exacerbation of psychotic symptoms and future risk due to substance abuse not be discharged from a healthcare setting due to their substance abuse [37, 43, 53]. Of the SMI guidelines, four guidelines highlighted the competency need of healthcare providers in each health care setting to consider for the co-existing disorders [47, 50, 52, 57]. Three out of seven SUD guidelines similarly covered competency aspects [42, 44, 46]. All coexisting disorder guidelines requested healthcare providers to gain training and expertise from other specialist staff in regards to either SMI or SUD [37,38,39] (Table 3).

Treatment of coexisting disorders

All of the guidelines related to SMI or coexisting disorders described the importance of screening and/or treatment for both problems simultaneously [37,38,39]. Three (27%) SMI guidelines stipulated SUD clinical guidelines and vice versa when recommending treatment of the other co-existing disorder (Table 4) [53, 55, 56]. One SUD guideline (14%) [45] however, did not explicitly provide recommendation regarding treatment of both disorders.

Only two out of the 11 (18%) SMI guidelines mentioned recommendation about treatment adjustments when considering dual diagnosis and treatment [49, 57]. Similarly, only three of the seven (43%) SUD guidelines mentioned recommendation about treatment adjustment [40, 41, 43] (Table 4). Examples of treatment adjustments included recommendation for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication in cases where there was a history of non-adherence to medication in place of regular antipsychotic medication [49]. Only one (33%) guideline of the coexisting disorders guidelines recommended the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication accordingly [37]. Two (67%) of the guidelines related to coexisting disorders [37, 39], five (45%) of SMI guidelines [51,52,53, 55, 56] and three (43%) of the SUD guidelines [42, 44, 46] considered potential drug interaction in patients with SMI and coexisting SUD. For example, the NICE (2011) guideline recommends that caution be exercised during the prescribing of medication for patients demonstrating substance abuse particularly that of alcohol, since alcohol will affect the metabolism of other medications and either diminish their efficacy or increase the risk of side effects [37] (Table 4).

Importance of physical health monitoring were described by all guidelines related to coexisting disorders, nine (82%) SMI guidelines, and four of the seven (57%) SUD guidelines. These included monitoring and management of diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia (Table 4).

Care pathway and integrated care provision

All of the coexisting disorders guidelines, seven (64%) of the SMI guidelines, and three (43%) of SUD guidelines mentioned the importance of continuity of care. For example, the Australian government guideline advised that it is important to develop systems in order to facilitate the transition of patients with coexisting disorders by providing them with much-needed services and helping them to address their complex needs [39] (Table 5).

Only one (33%) of the guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders mentioned that healthcare providers in the emergency department should regularly ask patients about any potential substance abuse [37]. Three (43%) of the guidelines related to SUD mentioned the role of the emergency department [42, 44, 46]. Such consideration was missing from SMI guidelines (Table 5).

Equity consideration and person-centered care

Three guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders, ten (91%) SMI guidelines, and six (86%) SUD guidelines described the essential role played by ‘significant others’ such as families and carers and encouraged their involvement along with any integrated care plans provided to patients (Table 6). All of the three guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders were explicit in reporting the need for assessment of any children cared for by patients with both disorders, according to safeguarding procedures. However, only three (27%) of the SMI guidelines and two (29%) of the SUD guidelines provided recommendations about children cared for by patients with both disorders (Table 6).

All of the guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders, five (45%) of the SMI guidelines, and two (29%) of the SUD guidelines mentioned the importance of ensuring that healthcare providers who provide care to patients with coexisting disorders should engage with patients from different ethnicities and cultural backgrounds (Table 6). Only the NICE 2011 offered advice to healthcare providers to solve access to care issues in patients [37] (Table 6).

Consideration of multiple social disadvantage

All of the guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders, nine (82%) of the SMI guidelines, and five (71%) of the SUD guidelines considered the assessment of risks of violence, suicide, and self-harm (Table 7). Two (67%) of the guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders highlighted the risk of certain getting involved with criminal justice system and the importance of prevention actions [37, 38]. Only the SMI guideline by Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) [50] and three (45%) of the SUD guidelines [42, 44, 46] highlighted the risk of patients being registered in the criminal justice system (Table 7).

All of the guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders, four (36%) of the SMI guidelines [47, 49, 50, 52], and two (29%) of the SUD guidelines [42, 44] attempted to inform the healthcare providers about the risk of homelessness as being a negative social outcome for individuals affected by SMI or SUD. However, only the Australian government mentioned the risk of homelessness in patients with coexisting disorders, but did not provide further recommendations about how such patients could receive support [39] (Table 7). Assessment of the history of any kind of abuse suffered by the patient, including sexual abuse were only rarely considered [37, 39, 42, 44, 52, 53, 55] (Table 7).

Issue of stigma and discrimination from healthcare providers were covered well by guidelines for co-existing disorders but less so by either SMI or SUD guidelines (Table 7).

Two (67%) of the guidelines pertaining to coexisting disorders, two (18%) of the SMI guidelines, and two (29%) of the SUD guidelines seemed to encourage seeking support from voluntary organizations [37, 38, 42, 44, 48, 50] (Table 7).

Discussion

This study provides an up-to-date assessment of the scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and/or substance abuse in relation to diagnosis and treatment of such co-existing disorders and consideration of wider social and contextual issues in treatment recommendations.

The overall quality of the included guidelines rated from a high to moderate quality. The ‘scope and purpose’ and ‘clarity of presentation’ domains were well addressed by the included guidelines. Previous systematic reviews have also demonstrated that clinical guidelines often score high in these domains [58,59,60]. For the ‘Stakeholder involvement’, it was noticed that there was a lack of incorporation of patient or public preferences in the guidelines development process. The ‘applicability’ domain was rated low amongst all the guidelines.

This review has demonstrated that there is a lack of clinical guidelines aimed to help healthcare professionals manage the dual diagnosis. More importantly any existing single disorder guidelines should incorporate coexisting disorders in diagnosis and treatment recommendations. These guidelines need to be consistent with current evidence that supported development of integral treatment model, strengthen the connection between mental health care setting and substance abuse services, and providing care for patients’ multiple disadvantages including wider social and contextual factors such as homelessness, involvement with criminal justice system [2, 15, 17].

Implication of practice and research

Until recently, most of the guidelines and recommendations addressed a single disorder; namely, either SMI or SUD. The result of this review suggests that a greater number of guidelines are required in order to cover dual diagnosis given the high overlap of the concurrent disorders.

Most single disorder guidelines included in this review did emphasize the importance of assessment of dual diagnosis. However, treatment adjustment for dual diagnosis was rarely described. Barriers of access to medicines, adherence issues requiring long acting depot injections, and drug interactions (including interactions with drug and substance of abuse) are key issues that require further considerations in single disorder guidelines.

There needs to be better emphasis on the integrated and inclusive care to be offered to the patients with dual diagnosis. Evidence suggests significant reductions in substance abuse, improvement in psychiatric symptoms, quality of life as well as social outcomes in relation to integrated models of management [61, 62]. However, traditional culture of specialist treatment centres that are focused on the treatment of a single condition, lack of expertise and resources are some of the barriers to provision of integrated care as described in the literature [29]. This review suggests that lack of clinical guidelines to offer integrated care could be contributing to the fragmented care. The need for liaison with emergency department, primary care, drug and alcohol services and hospital and specialist treatment centers also require further emphases. There is also scope to enhance cultural and ethnic specific issues in treatment recommendations.

It is well documented in the evidence that the treatment of coexisting disorders multifaceted and requires the continued assessment of many social and contextual issues of a patient. Social and contextual factors were not however uniformly addressed in the included guidelines. While risk of homelessness in patients with SMI, SUD or dual diagnosis was commonly described, further information to health providers to support prevention actions were often missing. It is imperative to signpost patients to housing assistance, volunteer sectors and social benefits system in order to prevent homelessness including repeat cycle of homelessness. Adequate evidence exist on the overlap between homelessness, SUD, SMI and dual diagnosis [63]. Persons who are homeless or risk facing homelessness often find accessing services difficult and future guidelines should consider addressing access issues better [21,22,23]. These include perceived stigma and discrimination in healthcare setting. Some guidelines described risks of homelessness with dual diagnosis. There are various barriers which patients experiencing homelessness and SUD must overcome in order to obtain housing due to their criminal record and economic status, all of which make them more susceptible to being submerged in their current negative environment and seem to increase the risk of relapse [64, 65].

Only a limited number of guidelines considered the continuity of care of offenders in community settings. It is known that treatment failure can trigger a return back to the patient’s offending behavior after their release from prison [66, 67].

There needs to be better emphases on the integrated and inclusive care to be offered to the patients with dual diagnosis. Liaison with emergency department, primary care, drug and alcohol services and hospital and specialist treatment centers require further emphases. There is also scope to enhance cultural and ethnic specific issues in treatment recommendations. Roles of community based services such as community pharmacy and voluntary sectors should be better stipulated in the guidelines [68,69,70,71].

Future research is need needed to cover healthcare professional, patient, carer and payer’s perspectives to identify ways to strengthen the guidelines and limitations and improve patient experiences of care and outcomes. It is also imperative to compare practices against the guideline recommendations. For example, research suggest that patients prescribed antipsychotic medicines are often poorly followed up for their cardiovascular and metabolic health in contrary to the recommendations from the guidelines [72]. Guideline development procedures should learn and share best practices being adopted in other countries.

The assessment of the quality of the guidelines using Agree II checklist suggested that the ‘Rigour of development’ domain scores were generally low as 15 out of 21 included guidelines rated below 70%. This domain captures how well did the guidelines provide evidence in relation to systematic search of relevant body of evidence-based literature, critical appraisal and expert review of the evidence. Further systematic and transparent approach needs to be adopted around the use and reporting of how evidence informed the guideline development.

In summary, this study reinforces the need for adaptation of international clinical guidelines so that healthcare professionals in diverse settings can undertake comprehensive assessment of patient with either SMI or SUD for dual diagnosis, consider assessment of wider social circumstances and consequences that are relevant to the dual diagnosis and adapt their treatment plans accordingly allowing better outcomes for patients, mitigate relapse of SMI, prevent repeat cycles of substance abuse and social consequences such as homelessness. This in turn have the potential to minimize healthcare costs and resource implications. Stakeholder should be involved in development of guidelines.

Study strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review to discuss coexisting disorders and aspects of their different complex needs. A comprehensive search was undertaken using databases and professional body web pages. Validated appraisal tool (AGREE II) was used for quality assessment. However, our search was restricted to English language guidelines only. In addition, we did not assess any supplementary patient screening, risk assessment and patient placement criteria that were not included or appended within the published guidelines.

Conclusion

Treatment guidelines for management of either SUD or SMI have tend to have limited considerations for dual diagnosis. There is a need for the guidelines to be more inclusive in order to enable better diagnosis and treatment and cover social cause and consequences of dual diagnosis such as homelessness. Further emphasis is also needed to promote effective transition of care across services and promotion of self-care after discharge. Professional societies should better communicate the guideline development process as well as rigour in relation to the inclusion and appraisal of evidence base in the guideline development process.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- SMI:

-

Severe mental illness

- SUD:

-

Substance use disorder

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- APA:

-

American Psychiatric Association

- US:

-

United States

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- GPs:

-

General practitioners

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5

- BAP:

-

British Association of psychopharmacology

- AUD:

-

Alcohol use disorder

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- SIGN:

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

- AGREE II:

-

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II

- AOD:

-

Alcohol and other drug

- WFSBP:

-

World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

- DGPPN and DG-Sucht:

-

German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Psychosomatics and the German Association for Addiction Research and Therapy

- ASAM:

-

American society of addiction medicine

- Singapore MOH:

-

Singapore Ministry of Health

- VA/DoD:

-

Department of Veterans Affairs and The Department of Defense

- CANMAT and ISBD:

-

Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments and International Society for Bipolar Disorders

- RANZCP:

-

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists

- Gov.uk:

-

United Kingdom guidelines on clinical management

- CAMHS:

-

Child and adolescent mental health services

References

Carrà G, Bartoli F, Brambilla G, Crocamo C, Clerici M. Comorbid addiction and major mental illness in Europe: a narrative review. Subst Abus. 2015;36(1):75–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.960551.

Fantuzzi C, Mezzina R. Dual diagnosis: a systematic review of the organization of community health services. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(3):300–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019899975.

McCreadie RG. Use of drugs, alcohol and tobacco by people with schizophrenia: case–control study. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(4):321–5. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.4.321.

Temmingh HS, Williams T, Siegfried N, Stein DJ. Risperidone versus other antipsychotics for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance misuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1.

Elliott I. Poverty and mental health: a review to inform the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Anti-Poverty Strategy. Available from: http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Poverty-and-Mental-Health.htm. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, McGorry PD. Substance misuse in first-episode psychosis: 15-month prospective follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189(3):229–34. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017236.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Comorbidity: substance use disorders and other mental illnesses drugfacts. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/publications/drug-facts. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Antai-Otong D, Theis K, Patrick DD. Dual diagnosis: coexisting substance use disorders and psychiatric disorders. Nurs Clin. 2016;51(2):237–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2016.01.007.

Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Drake RE. A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23(4):471–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230412331324590.

Lambert-Harris C, Saunders EC, McGovern MP, Xie H. Organizational capacity to address co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders: assessing variation by level of care. J Addict Med. 2013;7(1):25–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318276e7a4.

Hjorthøj C, Østergaard MLD, Benros ME, Toftdahl NG, Erlangsen A, Andersen JT, et al. Association between alcohol and substance use disorders and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression: a nationwide, prospective, register-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):801–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00207-2.

Lynskey MT, Kimber J, Strang J. Drug-related mortality in psychiatric patients. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):767–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00372-7.

Fridell M, Bäckström M, Hesse M, Krantz P, Perrin S, Nyhlén A. Prediction of psychiatric comorbidity on premature death in a cohort of patients with substance use disorders: a 42-year follow-up. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2098-3.

Fekadu W, Mihiretu A, Craig TKJ, Fekadu A. Multidimensional impact of severe mental illness on family members: systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12).

Lukasiewicz M, Blecha L, Falissard B, Neveu X, Benyamina A, Reynaud M, et al. Dual diagnosis: prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with suicide risk in a nationwide sample of French prisoners. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(1):160–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00819.x.

Polcin DL. Co-occurring substance abuse and mental health problems among homeless persons: suggestions for research and practice. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2016;25(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1179/1573658X15Y.0000000004.

Schütz C, Choi F, Jae Song M, Wesarg C, Li K, Krausz M. Living with dual diagnosis and homelessness: marginalized within a marginalized group. J Dual Diagn. 2019;15(2):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2019.1579948.

Buckley PF. Prevalence and consequences of the dual diagnosis of substance abuse and severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:5.

McLeod KE, Butler A, Young JT, Southalan L, Borschmann R, Sturup-Toft S, et al. Global prison health care governance and health equity: a critical lack of evidence. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(3):303–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305465.

Kelly TM, Daley DC. Integrated treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Soc Work Public Health. 2013;28(3–4):388–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.774673.

Gunner E, Chandan SK, Yahyouche A, Paudyal V, Marwick S, Saunders K, et al. Provision and accessibility of primary healthcare services for people who are homeless: a qualitative study of patient perspectives in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(685):E526–36. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X704633.

Paudyal V, Maclure K, Forbes-McKay K, McKenzie M, McLeod J, Smith ASD. If I die, I die, I don’t care about my health’: perspectives on self-care of people experiencing homelessness. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(1):160–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12850.

Paudyal V, MacLure K, Buchanan C, Wilson L, Macleod J, Stewart D. ‘When you are homeless, you are not thinking about your medication, but your food, shelter or heat for the night’: behavioural determinants of homeless patients’ adherence to prescribed medicines. Public Health. 2017;148:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.03.002.

Pinderup P. Challenges in working with patients with dual diagnosis. Adv Dual Diagn. 2018;11(2):60–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-11-2017-0021.

Sorsa M, Greacen T, Lehto J, Åstedt-Kurki P. A qualitative study of barriers to care for people with co-occurring disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(4):399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2017.04.013.

Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK, Roman PM. Availability of integrated care for co-occurring substance abuse and psychiatric conditions. Community Ment Health J. 2006;42(4):363–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-9030-7.

Murthy P, Chand P. Treatment of dual diagnosis disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(3):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328351a3e0.

Stewart SH, Conrod PJVO-19. State-of-the-art in cognitive-behavioral interventions for substance use disorders: introduction to the special issue. J Cogn Psychother. 2005;19(3):195.

McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Gotham HJ, Claus RE, Xie H. Dual diagnosis capability in mental health and addiction treatment services: an assessment of programs across multiple state systems. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2014;41(2):205–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0449-1.

Perron BE, Bunger A, Bender K, Vaughn MG, Howard MO. Treatment guidelines for substance use disorders and serious mental illnesses: do they address co-occurring disorders? Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(7–8):1262–78. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080903442836.

De Brún C. Finding the evidence: a key step in the information production process. Inf Stand Guid. 2013.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

American Pyschiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm. Accessed 07 Feb 2021

Mclellan AT. Substance misuse and substance use disorders: why do they matter in healthcare? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2017;128:112.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAG. 2010;182(18).

Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Consortium ANS. The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMG. 2016;352:i1152.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis with coexisting substance misuse: assessment and management in adults and young people. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK109783/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK109783.pdf. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

NICE. Coexisting existing severe mental illness and substance misuse : community health and social care services. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng58. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Marel C, Mills KL, Kingston R, Gournay K, Deady M, Kay-Lambkin F, et al. Co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings. Illustrations; 2016.

Lingford-Hughes AR, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt DJ. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: Recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(7):899–952. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881112444324.

Soyka M, Kranzler HR, Hesselbrock V, Kasper S, Mutschler J, Möller HJ. Guidelines for biological treatment of substance use and related disorders, part 1: alcoholism, first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2017;18(2):86–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2016.1246752.

Gov.uk. Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. 2021. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-misuse-and-dependence-uk-guidelines-on-clinical-management. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Preuss UW, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Havemann-Reinecke U, Schäfer I, Beutel M, Hoch E, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in alcohol use disorders: results from the German S3 guidelines. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(3):219–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-017-0801-2. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

NICE. Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking (high-risk drinking) and alcohol dependence. Available https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg115. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Reus VI, Laura Fochtmann CJ, Oscar Bukstein M, Evan Eyler MA, Donald Hilty MM, Horvitz-Lennon M, et al. The american psychiatric association practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder guideline writing group systematic review group steering committee on practice guidelines APA assembly liaisons. 2018. Available from: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615371969. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Comer S, Cunningham C, Fishman MJ, Gordon FA, Kampman FK, Langleben D, et al. National practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. Am Soc Addicit Med. 2015;66.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. SIGN 131 • Management of schizophrenia key to evidence statement and grades of recommendations Available from: http://sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign131.pdf.

NICE. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178. Accessed 07 February 2021.

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia part 3: update 2015 management of special circumstances: depression, Suicidality, substance use disorders and pregnancy and lactation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16(3):142–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2015.1009163.

Castle DJ, Galletly CA, Dark F, Humberstone V, Morgan VA, Killackey E, et al. The 2016 royal australian and New Zealand college of psychiatrists guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Med J Aust. 2017;206(11):501–5. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja16.01159.

Barnes TRE, Drake R, Paton C, Cooper SJ, Deakin B, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34(1):3–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881119889296.

Keepers GA, Anzia JM, Benjamin S, Lyness JM, Mojtabai R, Servis M, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia Guideline .https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/clinical-practice-guidelines. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guidline for management of bipolar disorder in adults; 2009. p. 1–176. Available from: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/bd/bd_305_full.pdf Accessed 07 Feb 2021

Mok YM, Chan HN, Chee KS, Chua T-E, Lim BL, Marziyana AR, et al. MOH clinical practice guidelines: bipolar disorder. Ministry of Health. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22159936/. Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

NICE. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/resources/bipolar-disorder-assessment-and-management-pdf-35109814379461 . Accessed 07 Feb 2021.

Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, Aronson JK, Barnes TRH, Cipriani A, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116636545.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12609.

Keating D, McWilliams S, Schneider I, Hynes C, Cousins G, Strawbridge J, et al. Pharmacological guidelines for schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparison of recommendations for the first episode. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013881. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013881.

Johnston A, Hsieh S-C, Carrier M, Kelly SE, Bai Z, Skidmore B, et al. A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines on the use of low molecular weight heparin and fondaparinux for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism: implications for research and policy decision-making. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207410.

Zhang P, Lu Q, Li H, Wang W, Li G, Si L, et al. The quality of guidelines for diabetic foot ulcers: a critical appraisal using the AGREE II instrument. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0217555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217555.

Ziedonis DM, Smelson D, Rosenthal RN, Batki SL, Green AI, Henry RJ, et al. Improving the care of individuals with schizophrenia and substance use disorders: consensus recommendations. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11(5):315–39. https://doi.org/10.1097/00131746-200509000-00005.

Morrens M, Dewilde B, Sabbe B, Dom G, De Cuyper R, Moggi F. Treatment outcomes of an integrated residential programme for patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorder. Eur Addict Res. 2011;17(3):154–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000324480.

Bowen M, Marshall T, Yahyouche A, Paudyal V, Marwick S, Saunders K, et al. Multimorbidity and emergency department visits by a homeless population: a database study in specialist general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(685):E515–25. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X704609.

Moxley VBA, Hoj TH, Novilla MLB. Predicting homelessness among individuals diagnosed with substance use disorders using local treatment records. Addict Behav. 2020;102:106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106160.

Padgett DK, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A. Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: comparing housing first with treatment first programs. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(2):227–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9283-7.

Field G. Continuity of offender treatment for substance use disorders from institution to community: treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series 30. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

Peters RH, Bartoi MG, Sherman PB. Screening and assessment of co-occurring disorders in the justice system. https://www.ce-credit.com/articles/100958/Screening_Assessment_Mono.pdf. Accessed 18 Mar 2021.

Paudyal V, Gibson Smith K, MacLure K, Forbes-McKay K, Radley A, Stewart D. Perceived roles and barriers in caring for the people who are homeless: a survey of UK community pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(1):215–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-019-00789-4.

Jagpal P, Saunders K, Plahe G, Russell S, Barnes N, Lowrie R, et al. Research priorities in healthcare of persons experiencing homelessness: outcomes of a national multi-disciplinary stakeholder discussion in the United Kingdom. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01206-3.

Jagpal P, Barnes N, Lowrie R, Banerjee A, Paudyal V. Clinical pharmacy intervention for persons experiencing homelessness: evaluation of patient perspectives in service design and development. Pharmacy. 2019;7(4):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7040153.

Alenezi A, Yahyouche A, Paudyal V. Interventions to optimize prescribed medicines and reduce their misuse in chronic non-malignant pain: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(4):467–90.

Ali RA, Jalal Z, Paudyal V. Barriers to monitoring and management of cardiovascular and metabolic health of patients prescribed antipsychotic drugs: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02990-6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data associated with the manuscript has been reported in the manuscript and supplemental materials.

Conflict of interest

No authors have any conflicts of interests to disclose.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work related to RA’s Master of Science in Toxicology study. DS, SA, and VP were the supervisors to the study. RL contributed through expert advice, critical review and significant input in the write up. RA led the write up to which all authors contributed through editing and recommendations. All authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Electronic supplemental material 1: PRISMA Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Electronic supplemental material 2: Search strategy.

Additional file 3.

Electronic supplemental material 3: AGREE II Score Sheet.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsuhaibani, R., Smith, D.C., Lowrie, R. et al. Scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and substance abuse in relation to dual diagnosis, social and community outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 21, 209 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03188-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03188-0