Abstract

Background

It is unclear whether the administration of antipsychotics to children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is acceptable, equitable, and feasible.

Methods

We performed a systematic review to support a multidisciplinary panel in formulating a recommendation on antipsychotics, for the development of the Italian national guidelines for the management of ASD. A comprehensive search strategy was performed to find data related to intervention acceptability, health equity, and implementation feasibility. We used quantitative data from randomized controlled trials to perform a meta-analysis assessing the acceptability and tolerability of antipsychotics, and we estimated the certainty of the effect according to the GRADE approach. We extracted data from systematic reviews, primary studies, and grey literature, and we assessed the risk of bias and methodological quality of the published studies.

Results

Antipsychotics were acceptable (dropouts due to any cause: RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.48–0.78, moderate certainty of evidence) and well tolerated (dropouts due to adverse events: RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.55–1.79, low certainty of evidence) by children and adolescents with ASD. Parents and clinicians did not raise significant issues concerning acceptability. We did not find studies reporting evidence of reduced equity for antipsychotics in disadvantaged subgroups of children and adolescents with ASD. Workloads, cost barriers, and inadequate monitoring of metabolic adverse events were indirect evidence of concerns for feasibility.

Conclusion

Antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD were likely acceptable and possibly feasible. We did not find evidence of concern for equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an early onset, neurodevelopmental disorder that causes a broad set of socio-communication deficits and restricted or repetitive behaviors. ASD is commonly associated with problem behaviors such as hyperactivity, irritability, and self-harm [1, 2]. ASD symptomatology causes reduced functioning, regardless of intellectual ability [3, 4]. The prevalence of ASD worldwide is about 1–2% [5], while in Italy, it is 1.14–1.3% [6, 7], with a male: female ratio of about 4:1. About 48% of children with ASD are affected by a form of intellectual disability [8, 9]. In the United Kingdom and the USA, the estimated lifelong costs to support an individual with ASD from the societal perspective range between 1.2 to 2 million euros, depending on the presence of intellectual disability [10].

Irritability and aggression are treatment targets for the use of antipsychotics in ASD [11]. The food and drug administration (FDA) approved risperidone and aripiprazole for the treatment of irritability in ASD, while there is no pharmacological treatment that has been proven to be effective in treating core symptoms [12].

It is not apparent whether antipsychotics are acceptable and feasible to a population of children and adolescents with ASD. Parents could be reluctant to administer antipsychotics to their children, and concern towards adverse events often leads parents to shift towards complementary and alternative medicines [12, 13]. Adverse events related to antipsychotics, such as increased appetite, weight gain, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia [14, 15], may also discourage clinicians from prescribing them in children and adolescents with ASD. Adverse events can as well lead to treatment discontinuation and switch to other drugs. Furthermore, children with ASD and developmental disabilities often show troubles in swallowing medications [16]. Parents often have to manage pill-swallowing difficulties on their own; they often use some form of coercion to achieve immediate compliance, but such behavior could lead children to develop anxiety, aversion to pills, and increased food selectivity [17].

In this study, we aimed to systematically review the evidence on acceptability, equity, and feasibility of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD.

Methods

Context

The Italian National Institute of Health (in Italian: Istituto Superiore di Sanità – ISS) is currently developing evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ASD in children and adolescents. Equity, acceptability, and feasibility are considered contextual factors able to influence recommendations developing when using the grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) evidence to decision framework. We conducted this systematic review to support the ISS autism guidelines panel in formulating a recommendation on the use of antipsychotics, according to the ISS manual [18]. This project was carried out in conjunction with a multidisciplinary panel, which included subject experts, people with ASD, and their caregivers.

The questions

We addressed the following clinically and public health relevant questions on the use of antipsychotics for children and adolescents with ASD:

-

What would be the impact of antipsychotics on health equity?

-

Are antipsychotics acceptable to key stakeholders?

-

Are antipsychotics feasible to implement?

Population

Children and adolescents aged 0–18 years, of both genders, with a primary diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

Intervention

Antipsychotics selected by Guidelines panel members, including aripiprazole, clozapine, haloperidol, levosulpiride, lurasidone, olanzapine, risperidone and trifluoperazine.

Outcomes

Equity: differences in the effectiveness of the intervention or in the importance of the problem predictable based on basic conditions present within disadvantaged subgroups [19, 20].

Acceptability: the probability for the key stakeholders to agree with the distribution of the net benefits, harms, and costs; the costs, or undesirable effects, to be paid in the short term to achieve the desirable effects or benefits in the future; the values associated with the desirable or undesirable effects [19]; discontinuation due to any cause when comparing the intervention versus placebo.

Feasibility: sustainability of the intervention considering barriers and facilitators to its implementation [19].

Types of studies included

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were different for the purposes of quantitative and qualitative synthesis and were established a priori before conducting database searches.

Quantitative synthesis

For the meta-analysis on acceptability, we included only RCTs. The inclusion of non-randomized studies in the meta-analysis would have introduced bias, as observational studies are prone to selection bias and confounding by indication. Studies eligible for inclusion: randomized controlled trials and non-randomized controlled trials (such as quasi-randomized, observational and experimental studies) evaluating acceptability, equity and feasibility of APs in children and adolescents with ASD; as we found a sufficient number of RCTs reporting data on the above-mentioned outcomes, we did not include non-randomized trials in the meta-analysis. We excluded: studies that that did not evaluate or report data about at least one criterion among acceptability, equity or feasibility; studies comparing two pharmacological interventions, without placebo arm; augmentation trials with no placebo arm; studies presenting pooled or post-hoc analyses of RCTs; studies whose design, population or intervention did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Qualitative synthesis

All types of randomized and non-randomized studies (including systematic reviews, surveys, cohort, or cross-sectional studies) evaluating acceptability, equity and feasibility of APs in children and adolescents with ASD as a major part of the study. All types of studies that did not assess acceptability, equity and feasibility were excluded; studies whose population or intervention did not meet our inclusion criteria were also excluded.

Literature search

The literature search was conducted up to January 2019. No language filters were applied. We searched Central, Medline, Embase, Web of Science, and PsycInfo. The search strategies are reported in Additional file 1.

Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers (GLD, FDC) independently screened titles and abstracts of the publications obtained by the search strategies. The same authors independently assessed the inclusion of the full text of studies that potentially satisfied inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by a consensus meeting or by a third reviewer (LA).

Two reviewers (GLD, FDC) independently extracted data. The full methodology followed for extracting data for each considered domain is in Additional file 2 [19, 21, 22].

Data analysis and synthesis

Quantitative data extracted from RCTs (discontinuation due to any cause and discontinuation due to adverse event) were analyzed by the Risk Ratio (RR) using a random effect model [23] and expressing uncertainty with its 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity between studies has been investigated by the Q-test, by the I-squared statistic (I-squared equal to or more than 50% was considered indicative of heterogeneity), and by visual inspection of the forest plots. To investigate differences in pooled effect estimates related to type of antipsychotic drug, we conducted a subgroup analysis presenting sub-total effect estimates for each drug in the forest plots. In order to evaluate the presence of a possible publication bias, we used the funnel plot method which shows on the x-axis the magnitude of the effect (effect size) versus the estimated precision of the study (most commonly the standard error of the estimated association) on the y-axis. In the absence of publication bias, the points representing the studies have a roughly symmetric funnel shape, in contrast, when there is publication bias, smaller, less precise studies show a significant positive effect suggesting that small negative studies were not published and leading to an asymmetric funnel.

For the two outcomes, we produced a summary of findings table as advised by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group [19, 24,25,26,27]. After evaluating the study limitations, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias, we attributed four levels (high, moderate, low, very low) to the certainty in the evidence, accompanying the results with a narrative statement [28].

We synthetized narratively data retrieved from systematic reviews and observational studies on acceptability, feasibility, and equity of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD.

We used the GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework criteria to present and summarize the results.

Quality assessment

Depending on the type of studies included we used different methods to assess the methodological quality. Regarding the studies included in the quantitative synthesis (RCTs), we used the Cochrane tool for risk of bias assessment [29], evaluating: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, providers and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting. We then created a ‘Risk of bias’ table for the included studies, thus indicating the study’s performance (low, high, or unclear risk of bias) in each of the domains mentioned above. Regarding the studies included in the qualitative synthesis we used the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for the quality assessment of case-control and cohort studies [30], and a modified version of NOS [31] for cross-sectional studies. We planned to use, but did not, the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, as we did not find any non-randomized study comparing APs to placebo in our population reporting outcomes of interest. To assess the methodological quality of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in our study, we used Amstar 2 [32].

Main text

Search strategy results

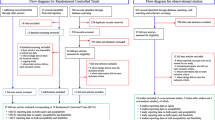

Through bibliographic searches, we identified 1388 reports after removing duplicates; we excluded 1266 studies on the basis of title and abstract. We retrieved 122 articles in full text for more detailed evaluation, 80 of which we excluded after reading the full text; of the remaining 42 studies, 35 were primary or secondary references referring to 15 RCTs [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], 6 were observational studies [48,49,50,51,52,53], and 1 was a systematic review [54]. See Fig. 1 for the flow chart, and Additional file 3 for the full references for included and excluded studies. We reported the methodological quality of included studies in Additional files 4, 5 and 6.

Equity

We did not find any study that reported data concerning equity in the use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD.

Acceptability

Acceptability by parents

Bowker et al. (2011) [48] carried out an online survey to investigate the motivations behind the therapeutic choice of parents of children and adolescents with ASD and their perception of the changes following the therapy undertaken. Nine hundred seventy questionnaires were collected (93% from North America), 96.4% from children and adolescents with ASD, and completed by parents. The survey showed that 77% of subjects had received therapy for ASD during their lifetime, but only 14.6% were on medication at the time the study was conducted. According to the parent’s judgment of the effectiveness of the treatment, the area of functioning that benefited most from drug therapy was behavioral (31.9%).

In contrast, a smaller number of parents indicated more notable benefits in the cognitive (16.3%), attention (14.2%), linguistic (12.8%), social (11.3%), and physical (3.5%) areas. Drug therapy was discontinued by 20% of the population. The reasons for discontinuation were mainly lack of efficacy (43% in total and 17% among those who had used antipsychotics at least once) and adverse events (29% in total and 11% among those who had used drug therapy at least once).

The same study reported some factors that parents considered determinant in choosing the type of treatment for their children with ASD, including:

-

a)

opinions about the causes of the disorder;

-

b)

parental style;

-

c)

lifestyle;

-

d)

socio-economic status;

-

e)

ease of access to services and care;

-

f)

impact of the media and the testimonies of other families.

The study concluded that the scientific evidence is not, for parents, decisive for the choice of treatments. Therapies supported by evidence are often underused, while frequently, non-evidence-based treatments are used. Non-evidence-based treatments can be potentially harmful, and the scientific community has a responsibility to explore all possible avenues to help parents to make well-informed decisions.

A survey [50] (n = 96 questionnaires administered), performed in the context of an RCT on the administration of risperidone versus placebo, found the following significant correlations between parent satisfaction and demographic characteristics: a) low income to poor satisfaction with the number of visits (p = 0.003); b) the child’s IQ ≥45 and white ethnicity with poor satisfaction to the learning tests (p = 0.043); c) the lower education to poor satisfaction with the behavioral assessment (P = 0.033).

Acceptability by children and adolescent with ASD

We found information on discontinuation due to any cause in 15 RCTs [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], and data on discontinuation due to adverse events in 12 RCTs [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 44,45,46,47]. We evaluated the risk of bias for the included RCTs (Additional file 4). We show forest plots of selected outcomes in Figs. 2 and 3. Based on visual inspection of funnel plots, we considered that publication bias was not likely (Additional file 7). Results of meta-analyses and certainty of evidence in effect sizes are reported in Table 1.

Actual use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD and predictive factors of their use

Jobski et al. (2017) [54] carried out a systematic review on the use of psychotropic drugs in individuals with ASD, identifying 47 studies that referred to a total of more than 300,000 individuals. In 15 of the 35 studies included in the review, antipsychotics were the most widely administered drugs. About 46% of the children considered across studies were taking psychotropic drugs, with a median prevalence of antipsychotic use of 17%.

About polypharmacological therapy, 22% of the children were taking several psychiatric drugs at the same time; The use of psychopharmacological products increased with age. The authors hypothesized some underlying causes for explaining this phenomenon: a) the development, during growth, of problem behaviors accompanied by an increase in physical strength; b) less reluctance to administer drugs by doctors and parents; (c) having already exhausted attempts at alternative treatments such as behavioral therapies. In addition, the authors noted a trend to switch from stimulants to antipsychotics and antidepressants as age increased, and this trend was attributed to the decrease in symptoms typical of comorbid Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, alongside the onset of other problem behaviors such as anxiety, aggression, and depression. Another study [49], conducted in the UK and not included in Jobski et al. (2017) systematic review [54], enrolled a cohort of 3482 children and adolescents with ASD; according to the authors, about 10% of the included population was using antipsychotics, mainly risperidone (55%) and aripiprazole (32%), always associated with psychosocial therapy. The authors identified the following socio-demographic predictors of the use of antipsychotics: adolescent age (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.16), low adaptive functioning inferred from the CGAS scale (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.95 to 0.97), aggressive and self-harm behaviors (OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.63) and parental concern for symptoms (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.27 to 3.22). Clinical predictors included hyperactivity (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.06), depression (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.37 to 4.09), obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OR 2).31, CI 95% from 1.16 to 4.61), tics (OR 2.76, CI 95% from 1.09 to 6.95), intellectual disability (OR 1.68, CI 95% from 1.11 to 2.53), and obviously psychosis (OR 5.71, CI 95% from 3.3 to 10.6).

Feasibility

In this section, we summarized barriers and facilitators to the implementation and sustainability of antipsychotics administration using the findings from the three included studies [51,52,53]. We did not find studies that included children with ASD, but we found three studies considering children with intellectual disabilities and decided to use this evidence to inform this domain.

Among facilitators, the authors identified:

-

1)

Nursing team. Nurses facilitate the monitoring of side effects and routine laboratory controls;

-

2)

Electronic medical records. Electronic medical records are useful tools to assess treatment effects, monitor side effects, and facilitate communication between doctors;

-

3)

Parental or caregiver support.

Among barriers, the authors identified:

-

1)

Electronic medical records. Although perceived by some as facilitators, they are also considered a burden. There is no possibility to follow some parameters of treatment effects and side effects. When the system offers the possibility to monitor specific symptoms or effects of treatment, the possibilities are inflexible and time-consuming;

-

2)

Workloads. The pressure and workloads experienced by health care professionals are barriers to the implementation of antipsychotics;

-

3)

Cost barriers for the choice of drug (e.g. first-generation antipsychotics vs. second-generation antipsychotics);

-

4)

Poor monitoring of metabolic adverse events of antipsychotics.

In Table 2, we summarized the results for all the considered EtD criteria.

Discussion

Antipsychotics are among the most widely prescribed drugs in children and adolescents with ASD, with a median prevalence of use of 17% [54]. This is in line with both the prevalence of irritability in this population, for which risperidone and aripiprazole are effective and indicated [12, 55,56,57,58], and the frequent comorbidity with schizophrenia spectrum disorders symptoms [59].

On the basis of the available evidence, we found that antipsychotics were likely acceptable, and their implementation was potentially feasible. We did not find any information in the literature regarding the relation between antipsychotics administration and health equity. This could be because health disparities have not been observed, not expected, or not explored.

Parents reported the most frequent causes of drug discontinuation to be lack of efficacy and adverse events [48]. The higher rate of adverse events shown by recent meta-analyses [15, 55] did not impact on discontinuation due to adverse events in our study. Moreover, according to a recent meta-analysis [60], antipsychotics had a reduced discontinuation due to lack of efficacy when compared against placebo. The reduced discontinuation may partially explain also the observed strong protective effect of the drugs on dropouts due to any cause.

We did not find any study focusing specifically on the feasibility of antipsychotics administration in children and adolescents with ASD. However, while no specific barriers seemed to arise from the analysis of the acceptability, some concerns about the feasibility of proper monitoring of adverse events remained when analyzing indirect evidence [51,52,53, 61]. The implementation of facilitators could help provide better monitoring and solve drug-related problems [51, 53, 61, 62]. We found no evidence for the equity.

Strengths and limitations

The conduct of evidence synthesis of contextual evidence that influences recommendations is an emerging field in systematic review research, and we believe that our attempt to provide such evidence is a strength. To inform each considered criterion of the EtD framework, we ran a comprehensive search strategy to retrieve both randomized and non-randomized evidence. We also performed a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to assess the acceptability and tolerability of antipsychotics for children and adolescents with ASD. In our opinion, the combination of quantitative and qualitative synthesis is an added study strength.

The use of the EtD framework in general, and the evaluation of its domains relating to equity, acceptability and feasibility, requires the panel to be familiar with the tool [63], and this is a potential limitation for the process of developing recommendations. To overcome this potential limitation, about 2 months before the presentation of the body of evidence on antipsychotics, an EtD framework on a pilot question was presented to the panel [64, 65]. In other experiences, panel members have reported that, when familiarity with the EtD framework is achieved, the tool helped them in structuring discussion, saving time, ensuring systematicity in the process of recommendation formulation [66].

Available evidence on acceptability, equity, and feasibility of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD needs to be evaluated by the panel together with evidence on efficacy, safety (D’Alò GL, De Crescenzo F, Amato L, et al; ISACA guideline working group. Impact of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis, forthcoming), resources required and cost-effectiveness in formulating a recommendation.

We have not prospectively registered on PROSPERO or other databases the protocol for our systematic review, and this is a study limitation. However, the clinical question was formulated by a multidisciplinary panel of experts, and the methodology followed for the development of the systematic review was based on the manual developed and published by the ISS [18, 67].

The results of a previously ongoing trial (NCT00198107) [68] were published on clinicaltrial.gov after the recommendation formulated by the panel and based on the present systematic review was submitted to public consultation. However, data were consistent with the results of our study for both “Discontinuation due to any cause” (RR 0.51, CI 0.14 to 1.91), and “Discontinuation due to adverse events” (RR 1.02, CI 0.07 to 15.83).

Conclusions

Antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD were likely acceptable and possibly feasible. We did not find evidence of concern for equity. Future clinical research needs to prioritize acceptable and feasible interventions that contribute to reducing health inequities [69].

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist is reported on Additional file 8.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting our findings is contained within the manuscript and the additional files.

The authors and can be contacted at f.decrescenzo@deplazio.it. (FDC) for further clarification, if required.

Abbreviations

- ASD:

-

Autism spectrum disorder

- D2:

-

Dopamine 2

- EtD:

-

Evidence to Decision

- GRADE:

-

grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation

- ISS:

-

Italian national institute of health

- NOS:

-

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: Author; 2013.

Farmer C, Thurm A, Grant P. Pharmacotherapy for the core symptoms in autistic disorder: current status of the research. Drugs. 2013;73(4):303–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0021-7.

Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. 2018;392(10146):508–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31129-2.

Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ. Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI32483.

Christensen DL, Braun KVN, Baio J, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;65(13):1–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6513a1.

Narzisi A, Posada M, Barbieri F, Chericoni N, Ciuffolini D, Pinzino M. Prevalence of autism Spectrum disorder in a large Italian catchment area: a school-based population study within the ASDEU project. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;29:e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000483.

Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Giornata mondiale della Consapevolezza dell’Autismo: in Italia un bimbo ogni 77. 2019. Available at: https://www.iss.it/?p=3421. Accessed: 31 Dec 2019.

Postorino V, Fatta LM, Sanges V, Giovagnoli G, De Peppo L, Vicari S, et al. Intellectual disability in autism Spectrum disorder: investigation of prevalence in an Italian sample of children and adolescents. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;48:193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.10.020.

Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):896–910.

Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):721–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210.

Park SY, Cervesi C, Galling B, Molteni S, Walyzada F, Ameis SH, et al. Antipsychotic Use Trends in Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorder and/or Intellectual Disability: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(6):456–468.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.03.012.

Goel R, Hong JS, Findling RL, Ji NY. An update on pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(1):78–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1458706.

DeFilippis M. The use of complementary alternative medicine in children and adolescents with autism Spectrum disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018;48(1):40–63.

Krill RA, Kumra S. Metabolic consequences of second-generation antipsychotics in youth: appropriate monitoring and clinical management. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2014;5:171–82.

Alfageh BH, Wang Z, Mongkhon P, Besag FMC, Alhawassi TM, Brauer R, Wong ICK. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic medication in individuals with autism Spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Drugs. 2019;21(3):153–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-019-00333-x.

Schiff A, Tarbox J, Lanagan T, Farag P. Establishing compliance with liquid medication administration in a child with autism. J Appl Behav Anal. 2011;44(2):381–5.

Ghuman JK, Cataldo MD, Beck MH, Slifer KJ. Behavioral training for pill-swallowing difficulties in young children with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(4):601–11.

Istituto Superiore di Sanità – Centro Nazionale per l’Eccellenza Clinica, la Qualità e la Sicurezza delle Cure. (ISS-CNEC) Manuale metodologico per la produzione di linee guida di pratica clinica. 2018. Available at: https://snlg.iss.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/MM_v1.2_lug-2018.pdf Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from: guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook. Accessed 16 Jan 2020.

Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Fretheim A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 12. Incorporating considerations of equity. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4:24.

O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, Petticrew M, Pottie K, Clarke M, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:56e64.

Welch VA, Akl EA, Guyatt G, Pottie K, Eslava-Schmalbach J, Ansari MT, et al. GRADE equity guidelines 1: considering health equity in GRADE guideline development: introduction and rationale. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;90:59–67.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Santesso N, Helfand M, Vist G, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 12. Preparing summary of findings tables-binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(2):158–72.

Guyatt GH, Thorlund K, Oxman AD, Walter SD, Patrick D, Furukawa TA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 13. Preparing summary of findings tables and evidence profiles-continuous outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(2):173–83.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The CochraneCollaboration; 2011. Available from www.handbook.cochrane.org.

Santesso N, Glenton C, Dahm P, Garner P, Akl E, Alper B, GRADE Working Group, et al. GRADE guidelines 26: Informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019 [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Cochrane Bias Methods Group, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Wells G, Shea B, O'connell DL, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. (2014). The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp Accessed: 16 Jan 2020.

Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, Agyemang C, Remuzzi G, Rapi S, ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings, et al. Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147601.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.

Campbell M, Anderson LT, Meier M, Cohen IL, Small AM, Samit C, et al. A comparison of haloperidol and behavior therapy and their interaction in autistic children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978;17(4):640–55.

Findling RL, Mankoski R, Timko K, Lears K, McCartney T, McQuade RD, et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the safety and efficacy of aripiprazole in the long-term maintenance treatment of pediatric patients with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):22–30. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08500.

Hollander E, Wasserman S, Swanson EN, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of olanzapine in childhood/adolescent pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):541–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2006.16.541.

Ichikawa H, Mikami K, Okada T, Yamashita Y, Ishizaki Y, Tomoda A, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism Spectrum disorder in Japan: a randomized, double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017;48(5):796–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0704-x.

Kent JM, Kushner S, Ning X, Karcher K, Ness S, Aman M, et al. Risperidone dosing in children and adolescents with autistic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(8):1773–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1723-5.

Loebel A, Brams M, Goldman RS, Silva R, Hernandez D, Deng L, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of irritability with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46:1153–63.

Luby J, Mrakotsky C, Stalets MM, Belden A, Heffelfinger A, Williams M, et al. Risperidone in preschool children with autistic spectrum disorders: an investigation of safety and efficacy. J Child Adoles Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):575–87. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2006.16.575 PMI.

Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, Manos G, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Aman MG. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1110–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76658.

McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, Cronin P, Hong D, Aman MG, et al. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):314–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa013171 PMID: 12151468.

Nagaraj R, Singhi P, Malhi P. Risperidone in children with autism: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(6):450–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738060210060801.

NCT00870727. Study of Aripiprazole in the Treatment of Pervasive Developmental Disorders. First posted: 27th Mar 2009. Accessed: 18 Feb 2019.

NCT01624675. A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Risperidone (R064766) in Children and Adolescents With Irritability Associated With Autistic Disorder. First posted: 21st Jun 2012. Accessed: 18 Feb 2019.

Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, Corey-Lisle P, Manos G, McQuade RD, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1533–40. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3782.

Remington G, Sloman L, Konstantareas M, Parker M, Gow R. Clomipramine versus haloperidol in the treatment of autistic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21(4):440–4.

Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, Schulz M, Orlik H, Smith I, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e634–e41.

Bowker A, D'Angelo NM, Hicks R, Wells K. Treatments for autism: parental choices and perceptions of change. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(10):1373–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1164-y.

Downs J, Hotopf M, Ford T, Simonoff E, Jackson RG, Shetty H, et al. Clinical predictors of antipsychotic use in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: a historical open cohort study using electronic health records. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(6):649–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0780-7.

Tierney E, Aman M, Stout D, Pappas K, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, et al. Parent satisfaction in a multi-site acute trial of risperidone in children with autism: a social validity study. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(1):149–57.

Ramerman L, Hoekstra PJ, de Kuijper G. Exploring barriers and facilitators in the implementation and use of guideline recommendations on antipsychotic drug prescriptions for people with intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31(6):1062–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12461.

Rodday AM, Parsons SK, Mankiw C, Correll CU, Robb AS, Zima BT, et al. Child and adolescent psychiatrists' reported monitoring behaviors for second-generation antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(4):351–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2014.0156.

Ronsley R, Raghuram K, Davidson J, Panagiotopoulos C. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of a metabolic monitoring protocol in hospital and community settings for second-generation antipsychotic-treated youth. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(2):134–41.

Jobski K, Höfer J, Hoffmann F, Bachmann C. Use of psychotropic drugs in patients with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(1):8–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12644.

Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, Rusiecki D, Bennett TA, Beyene J. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168–80. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2018.0115.

Lee ES, Vidal C, Findling RL. A focused review on the treatment of pediatric patients with atypical antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(9):582–605. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2018.0037.

Fung LK, Mahajan R, Nozzolillo A, Bernal P, Krasner A, Jo B, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of severe irritability and problem behaviors in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(Suppl 2):S124–35. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2851K.

Robb AS. Managing irritability and aggression in autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16(3):258–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/ddrr.118.

De Giorgi R, De Crescenzo F, D'Alò GL, Rizzo Pesci N, Di Franco V, Sandini C, et al. Prevalence of Non-Affective Psychoses in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091304.

Pillay J, Boylan K, Carrey N, Newton A, Vandermeer B, Nuspl M, et al. First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Children and Young Adults: Systematic Review Update. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442352/PubMed PMID: 28749632.

Javaheri KR, McLennan JD. Adherence to antipsychotic adverse effect monitoring among a referred sample of children with intellectual disabilities. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):235–40. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2018.0167.

Wongpakaran R, Suansanae T, Tan-Khum T, Kraivichian C, Ongarjsakulman R, Suthisisang C. Impact of providing psychiatry specialty pharmacist intervention on reducing drug-related problems among children with autism spectrum disorder related to disruptive behavioural symptoms: a prospective randomized open-label study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(3):329–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12518.

Moberg J, Oxman AD, Rosenbaum S, Schünemann HJ, Guyatt G, Flottorp S, GRADE Working Group, et al. The GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0320-2.

D’Alò GL, De Crescenzo F, Minozzi S, Morgano GP, Mitrova Z, Scattoni ML, ISACA guideline working group, et al. Equity, acceptability and feasibility of using polyunsaturated fatty acids in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a rapid systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):101.

De Crescenzo F, D’Alò GL, Morgano GP, Minozzi S, Mitrova Z, Saulle R, ISACA guideline working group, et al. Impact of polyunsaturated fatty acids on patient-important outcomes in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):28.

Rosenbaum SE, Moberg J, Glenton C, Schünemann HJ, Lewin S, Akl E, et al. Developing evidence to decision frameworks and an interactive evidence to decision tool for making and using decisions and recommendations in health care. Global Chall. 2018;2(9):1700081. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.201700081.

Morgano GP, Fulceri F, Nardocci F, Barbui C, Ostuzzi G, Papola D, Italian National Institute of Health guideline working group on Autism Spectrum Disorder, et al. Introduction and methods of the evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and management of autism spectrum disorder by the Italian National Institute of Health. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01320-4.

NCT00198107. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Aripiprazole and D-Cycloserine to Treat Symptoms Associated With Autism. Available at: clinicaltrial.gov. Results published on March 29, 2019, after the completion of our systematic review for the ASD guidelines development purpose. Accessed: 18 Dec 2019.

Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013.

Acknowledgments

Members of ISACA guideline working group

Collaborating author names from the ISACA guideline working group: Raffaella, Tancredi; Angelo, Massagli; Giovanni, Valeri; Corrado, Cappa; Serafino, Buono; Giuseppe Maurizio, Arduino; Alessandro, Zuddas; Laura, Reali; Massimo, Molteni; Claudia, Felici; Concetta, Cordò; Lorella, Venturini; Cristina, Bellosio; Emanuela, Di Tommaso; Sandra, Biasci; Clelia M, Duff; Simona, Vecchi; Michele, Basile.

Funding

Italian Ministry of Health Project ‘I disturbi dello spettro autistico: attività previste dal decreto ministeriale del 30.12.2016 – capitolo 4395 (articolo 1, comma 401, legge 28 dicembre 2015, n. 208, recante “Disposizioni per la formazione 661 del bilancio annuale e pluriennale dello Stato (legge di stabilità 2016)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: GLD, FDC, SM, GPM, HJS, LA. Data curation: GLD, FDC, ZM, MD, LA. Formal analysis: FDC, GLD, LA. Project administration: MD, FN, HJS, LA, MLS. Supervision: MLS, MD, FN, HJS, LA. Writing – original draft: GLD, FDC, LA. Writing – review & editing: MLS, FF, FC, RS, SM, ZM, MD, GPM, FN, HJS, LA. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Istituto Superiore di Sanità Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children and Adolescent guideline working group (ISACA guideline working group). Participants to the ISACA guideline working group are listed in the acknowledgments section.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy and results.

Additional file 2.

Full methodology for data extraction.

Additional file 3.

References for included and excluded studies, with reasons.

Additional file 4.

Risk of bias summary.

Additional file 5.

Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Additional file 6.

AMSTAR 2.

Additional file 7.

Funnel plots.

Additional file 8.

PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Alò, G.L., De Crescenzo, F., Amato, L. et al. Acceptability, equity, and feasibility of using antipsychotics in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 20, 561 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02956-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02956-8