Abstract

Background

Adolescents with 46,XY disorders of sex development (DSD) face additional medical and psychological challenges. To optimize management and minimize hazards, correct and early clinical and molecular diagnosis is necessary.

Case presentation

We report a 13-year-old Chinese adolescent with absent Müllerian derivatives and suspected testis in the inguinal area. History, examinations, and assistant examinations were available for clinical diagnosis of 46,XY DSD. The subsequent targeting specific disease‐causing genes, comprising 360 endocrine disease-causing genes, was employed for molecular diagnosis. A novel variation in nuclear receptor subfamily 5 group A member 1 (NR5A1) [c.64G > T (p.G22C)] was identified in the patient. In vitro functional analyses of the novel variant suggested no impairment to NR5A1 mRNA or protein expression relative to wild-type, and immunofluorescence confirmed similar localization of NR5A1 mutant to the cell nucleus. However, we observed decreased DNA-binding affinity by the NR5A1 variant, while dual-luciferase reporter assays showed that the mutant effectively downregulated the transactivation capacity of anti-Müllerian hormone. We described a novel NR5A1 variant and demonstrated its adverse effects on the functional integrity of the NR5A1 protein resulting in serious impairment of its modulation of gonadal development.

Conclusions

This study adds one novel NR5A1 variant to the pool of pathogenic variants and enriches the adolescents of information available about the mutation spectrum of this gene in Chinese population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

46,XY disorders/differences of sex development (DSD) occur with a frequency of approximately 1:20,000 [1] and encompass complete or partial gonadal dysgenesis, undervirilisation or under-masculinisation of an XY male due to genetic variation, abnormal hormone secretion, or abnormal changes in peripheral sensitivity to testosterone [2, 3]. A great proportion of 46,XY is caused by mutations in key transcription factors required for sex differentiation and androgen biosynthesis or action [2]. Compared with other age stages, adolescents with 46,XY DSD face additional medical and psychological challenges, which are particularly prominent and difficult for newly diagnosed adolescents [3]. To optimize management and minimize hazards, correct and timely diagnosis is necessary [3]; however, the diagnosis rate of 46,XY DSD with gonadal hypoplasia is exceptionally low [4], with > 50% of patients not receiving a molecular diagnosis [5, 6]. Clinical, biochemical, and imaging tests are recommended as the initial method for all suspected DSD patients. The classic diagnostic approach emphasizes obtaining these assessments before conducting genetic analyses (often limited to individual candidate genes) and is expensive, laborious, and time-consuming. The new approach proposes genetic testing as the first-line investigation after karyotyping and selective subsequent investigation to detail the phenotype [7, 8]. We implemented both approaches in parallel in the diagnosis of a Chinese adolescent with 46,XY DSD. The diagnostic process was extensive. According to the medical history, physical examinations, karyotyping, gonadotropin levels test, and ultrasound examinations, it was not difficult to obtain clinical diagnosis as 46,XY DSD. The subsequent genetic sequencing provided with the molecular diagnosis as a novel variant of NR5A1 c.64G > T (p.G22C).

Nuclear receptor subfamily 5 group A member 1 (NR5A1, also known as SF-1, AD4BP and FTZF1) is a key transcription factor that determines gonadal development and regulates coordinates endocrine functions [9]. NR5A1 variants occur in ~ 15–20% of patients and are regarded as a common genetic pathogeny of 46,XY DSD [5, 10, 11]. Achermann et al. [12] described the first two NR5A1 variants in individuals with 46,XY DSD who presented primary adrenal insufficiency and complete gonadal dysgenesis. Additionally, Pedace et al. [13] reviewed 61 NR5A1 variants among 81 cases with 46,XY DSD in 2014, while Fabbri-Scallet et al. [6] reported an update of 188 variants of NR5A1 in 238 cases with 46,XY DSD in 2020. These studies revealed that pathogenic variants are reported in 35–45% of individuals with 46,XY DSD [8, 11, 14]; however, there were very few cases diagnosed in adolescence. In addition, the evidence supported by experimental data is imperative to determine the role of these variants in 46,XY DSD [2]. Here, we describe the diagnostic process of a Chinese adolescent with 46,XY DSD and share our experience to bringing more attention to adolescents with 46,XY DSD. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report of the c.64G > T (p.G22C) NR5A1 variant; in vitro functional study of this novel variant will expand our knowledge of the NR5A1 mutational spectrum.

Case presentation

The adolescent was 13-years-old female initially treated for right lower abdominal pain. When the patient came back to the hospital for a check, the ultrasound examination showed absent Mullerian derivatives and suspected testis in the inguinal area. Since then, it has opened a complicated visit for nearly 10 months (Supplementary Fig. 1). The patient is the only child of healthy nonconsanguineous parents and was born through caesarean birth at 39 weeks of gestational age. The adolescent presented with breast in Tanner stage 1, undeveloped female external genitalia and suspected testicular tissue in double inguinal area. The External Genital Score (EGS) of the patient was 1, indicating that the patient's external genitalia is closer to that of female. The patient did not have symptoms or signs of adrenal insufficiency. The laboratory examinations (Table 1) suggested hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, 46,XY karyotype, and present SRY gene. The levels of AMH and inhibin B in this patient, evaluated by referring to the reference values in the literatures [15, 16], were significantly decreased. These clinical data (Fig. 1) supported the diagnosis as 46,XY DSD.

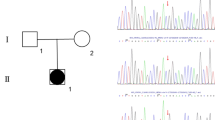

To obtain the molecular diagnosis, the subsequent genetic sequencing was performed. As chromosome microdeletion and microduplication are pathogenic factors associated with DSD, the copy number variation sequencing (CNV-seq) was performed firstly and the results indicated that there was no pathogenic variation in the patient at the chromosome level (Fig. 2A). Secondly, the targeting specific disease‐causing genes (TRS) was implemented as previously reported [17]. In brief, the exons and adjacent intron regions (± 50 bp) of 360 endocrine disease-causing genes (including DSD-causing genes; Supplementary Table 1) were captured. The sequencing results were analyzed using the related software and then a NR5A1 variant the candidate variation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing from the adolescent and parental samples. Pathogenicity analysis identified a de novo c.64G > T (p.G22C) heterozygous and missense variant in NR5A1 that was absent in the parents (Fig. 2B). This novel variant replaced guanine with thymine at nucleotide 64 in exon 2(Fig. 2C), leading to a glycine (Gly)-to-cysteine (Cys) substitution at position 22 in the DNA-binding domain (DBD) (Fig. 2D). Gly22 resides is highly conserved in different species (Fig. 2E). Additionally, function prediction identified this variation in NR5A1 as harmful (Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, these findings suggested the novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) variation in NR5A1 as the genetic cause of 46,XY DSD. In this present study, we implemented both the classic and new approach in parallel for the diagnosis of 46,XY DSD in an adolescent resulting from a c.64G > T (p.G22C) NR5A1 variant. The diagnostic process is shown in Fig. 3.

The sequencing results and bioinformatics analysis of mutation site. A CNV-seq analysis results showed the identification of 46,XY with no chromosome aneuploidy and genome copy number variation > 100 kb. B Sanger sequencing results for the NR5A1 mutation site in the patient and parents. The red arrow shows the mutation site. C Schematic representation of the c.64 G > T variant located in exon 2 of NR5A1. D Schematic representation of the G22C substitution in the NR5A1 DBD. E Conservation of Gly22 across species

The diagnostic approaches for the diagnosis of 46,XY DSD. The “classic” and “new” approaches for the diagnosis of 46,XY DSD are summarized in the left and right panels, respectively. The purple dotted line boxes indicate the first-line information for diagnosis. We implemented both approaches in parallel during the diagnostic process of 46,XY DSD in this study

Following the molecular diagnosis, further investigations are warranted to determine a more accurate phenotype. The three-day human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) stimulation test and seven-day human menopausal gonadotropin (HMG) stimulation test were performed to further assess gonad function. Negative results (Table 1) indicated that both testicular endocrine function and ovarian endocrine function were poor.

Subsequent issues involved treatment and gender assignment/reassignment. Psychological assessment revealed that the gender identity of the patient was female, which coincided with the social gender. The multi-disciplinary treatment team of DSD in our hospital conducted extensive and in-depth counseling with the adolescent and parents. Following the family agreeing to surgery, exploration results revealed absent Müllerian derivatives with blind vagina and poorly developed testicular tissue in the inguinal region without spermatogenic cells, which were confirmed by intraoperative frozen pathology and postoperative microscopic biopsy (Fig. 4). With the parents’ full knowledge and consent, the patient underwent bilateral gonadectomy. The surgical findings suggested that the patient had partial gonadal dysgenesis, which agreed with the clinical data. After careful consideration, the final decision of the family was that the gender of the adolescent to remain female.

The micrograph of gonad histology of the patient (hematoxylin and eosin staining). A Epididymal structure showing the epididymal duct surrounded by pseudostratified columnar epithelium. The cavity surface is flat, and circular smooth muscle fibers are observed outside of the epithelium (Magnification: 100 ×). B&C Spermatogenic tubules and interstitial cells can be seen in testicular tissue. There are only Sertoli cells in seminiferous tubules rather than definite spermatogenic cells. Small clusters of interstitial cells were observed among seminiferous tubules (the areas are outlined by the red lines in Fig. C). (Magnification: B, 100 × ; C, 200 ×)

The patient returned to our department for estrogen-replacement therapy (ERT) nearly 4 months after the surgery. We performed selective examinations of the patient at age 13 (Table 1), which revealed the following: height of 161 cm (75th to 90th percentile of height for girls of the same age and the same ethnic group); weight of 64.3 kg (> 90th centile); BMI of 24.8; bone age of 12.5-years old. The blood pressure was normal at 111/73 mmHg. The patient was treated with a low dose of oral progynova (250 μg; Bayer Vital GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany). The breasts developed to Tanner stage 2, and estrogen levels increased after ERT. The patient received regular follow-up and ERT for > 9 months with no adverse drug reactions.

Like this case, the novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) variation in NR5A1 also aroused our interest. The differences in the structural conformations of the WT and NR5A1-Mut variants were evaluated using the NR5A1 structure (Protein Data Bank ID: 4QJR). Despite the G22C substitution, both WT Gly22 and NR5A1-Mut Cys22 form hydrogen bonds with threonine at position 29 (Thr29) (Supplementary Fig. 2). According to the root-mean-square deviation between the WT and NR5A1-Mut (0.126), the results suggested that the G22C variant results in minimal alteration of the three-dimensional conformation of NR5A1.

What’s more, in vitro functional verification experiment on the novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) variation in NR5A1 were conducted. 293 T cells (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA), Myc-NR5A1 WT (WT) and Myc-p.G22C (NR5A1-Mut) plasmids, were used to conduct the NR5A1-overexpression system. qRT-PCR analysis showed no difference in NR5A1 mRNA levels between cells transfected with WT or NR5A1-Mut plasmids (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis subsequently confirmed that the protein of both WT and NR5A1-Mut groups was expressed at the same size (~ 53 kDa) and nearly the same level (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 3A&B). Immunofluorescence results revealed that WT and NR5A1-Mut localized exclusively to the nucleus (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the G22C substitution did not affect NR5A1 subcellular distribution. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed to determine the DNA-binding properties of the mutant. The results showed that the G22C substitution decreased the DNA-binding affinity of NR5A1 (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Fig. 3C). To determine transcriptional activity, the dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed using NR5A1 responsive promoter fragments of the human AMH gene. As shown in Fig. 5E, transactivation activity of the p.G22C mutant was clearly impaired.

Functional analyses of the NR5A1 mutant. A NR5A1 mRNA levels in 293 T cells according to qRT-PCR analysis: non-transfected (Control) and transfected with an empty vector (Vector), Myc-tagged WT (WT), or c.64G > T (p.G22C) NR5A1-Mut (Mut) vectors. B NR5A1 expression in 293 T cells according to western blot analysis (same grouping as A, the raw figures in Supplementary Fig. 3A&B.). C Nuclear localization of the NR5A1 mutant according to immunocytochemical analysis (same grouping as A). Scale bar, 50 μm. D EMSAs results showing altered DNA binding by the NR5A1 mutant. Nuclear extracts were prepared from four groups of cells (same grouping as A, the raw figures in Supplementary Fig. 3C). E Transcriptional activity of the NR5A1 mutant. Dual-luciferase activity detected in cells co-transfected with the WT plasmid and AMH reporter or the NR5A1-Mut plasmid and AMH reporter. The internal fluorescence reference was pRL-TK Renilla luciferase; t-test was applied for.*p < 0.05

Discussion and conclusions

Although the diagnosis of 46,XY DSD is rare, the impact on the life quality of the affected adolescents and their families is significant even devastating [12]. Physicians involved in 46,XY DSD diagnoses agree that more work is required in this area. In the previous study, both the classic and new approach in parallel for the diagnosis were successfully implemented in a Chinese infant with 46,XY DSD [18]. In the present study, we proceeded the approach for the diagnosis of partial gonadal dysgenesis in a Chinese adolescent with resulting from a c.64G > T (p.G22C) NR5A1 variant. Advanced genetic detection is applied as a first line of investigation for a molecular diagnosis and helpful to the etiologic diagnosis of patients with DSD and progressively improves the etiologic diagnostic rate [5, 7]. Following molecular diagnosis, further investigations are warranted to determine a more accurate phenotype and minimize unnecessary testing, sampling, and analysis. Molecular diagnosis allows a more reasonable sex assignment/re-assignment process and often helps individuals and families to cope with uncertainty, potential stigma, and accusations [10, 19], which are of great significance for adolescents with 46,XY DSD and their families. The application of these steps in the present case resulted in satisfactory follow-up treatment of the adolescent patient.

The emergence of new genetic techniques strongly influences the rate of correct diagnoses and reduces diagnostic delay [20]. The previous studies revealed a diagnostic rate of pathogenic variants identified in 46,XY DSD of ~ 40–66% [21]. In the present study, we identified a NR5A1 mutational site using TRS in a Chinese adolescent with 46,XY DSD. This novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) variant is a heterozygous variant, similar to most reported NR5A1 variants [6, 22,23,24]; however, the patient presented only gonadal dysgenesis without adrenal insufficiency. Heterozygous variants constitute the overwhelming majority of NR5A1 variants in human [6].

To date, the reported NR5A1 variants include missense and small deletions and insertions [6]. The novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) variant reported in the present study is a missense variant, which reportedly accounts for 58% of NR5A1 variants [6]. The p.G22C substitution is located in the DBD, which is one of three domains in NR5A1, and previous studies have reported this as the location for multiple variants in patients with 46,XY DSD [6, 22, 24,25,26]. A previous study identified a G35E substitution in the DBD region in a patient with 46,XY DSD presenting adrenal insufficiency along with moderately severe gonadal dysgenesis, indicating that this variation results in serious adverse effects on NR5A1 function [22]. Additionally, the p.V15M, p.M78I, and p.G91S variations in this region are reportedly responsible for aberrant NR5A1 transcription, with the first two variations resulting in altered subcellular localization [23]. Moreover, functional studies have shown that the p.S32N, p.N44del, and p.G91D variations in this region reduce the transactivation of cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1 [25]. In the present study, functional analyses suggested that the p.G22C variant demonstrated a decreased ability to bind DNA, resulting in significantly reduced levels of AMH transcription.

Interestingly, the site of the amino acid substitution reported here (G22C) is the same as that described by Sudhakar et al. [27] (G22S); however, the phenotype of the two patients is completely different. The patient (G22S) has very small penis, penoscrotal hypospadias, and hypoplastic scrotum with reduced rugosity at age of 9 years old, with less failure degree of male sexual characteristics development than the current patient (G22C). These findings reinforce the difficulty associated with establishing a concise phenotype–genotype correlation in 46,XY DSD diagnoses.

Furthermore, although previous studies suggest that some NR5A1 variants alter the 3D structure of the protein [25, 28], we found that the p.G22C substitution has no effect on NR5A1 structure. However, subsequent functional verification suggested this site as pathogenic, indicating the need for further mechanistic studies.

AMH secreted by Sertoli cells immediately after testicular differentiation, is responsible for the regression of Müllerian ducts in the male fetus [29]. The state of the Müllerian derivatives reflects the effect of AMH secreted very early in fetal life [29]. The absent Müllerian derivatives in this patient indicated that AMH still perfectly performs the responsibility for the regression of Müllerian ducts, even though NR5A1 variant may affect its function of promoting the secretion of AMH. In the human fetus at 9 weeks, Müllerian ducts have nearly totally disappeared [29]. It suggested that AMH was normal at least before 9 fetal weeks. The female external genitalia and dysplasia testicular tissue may be due to impaired androgens or androgen receptor secretion or action.

This patient was diagnosed with 46,XY DSD during adolescent years. The foreign and sudden disorders is undoubtedly an alarming and traumatic event for the adolescent and families. They have to face with some problems, including impaired fertility, medical treatment and possibly gonadal or vaginal surgery [3]. Sexuality is a sensitive topic for most Chinese families, and parents often avoid talking about it with children. The adolescent and parents experienced these painful sufferings. With the support and help of professionals in MDT of our hospital, they had slowly accepted all. It is only one case, however, we will continue to pay attention to DSD adolescents and look forward to sharing more with you in the future.

In summary, we described the diagnostic process for a 13-year-old Chinese patient with partial gonadal dysgenesis, including clinical and molecular diagnoses. Functional analysis identified a novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) variant in NR5A1 as a pathogenic variant that resulted in the NR5A1-mediated dysregulation of gonadal development. This study adds one more NR5A1 variant to the long list of previously published data for this gene and enriches the adolescents of information available about the NR5A1 mutation spectrum in Chinese population. Genetic analysis of more samples of NR5A1 variants and functional studies would be of great significance for understanding the mechanism of gonadal development and sex determination.

Availability of data and materials

The gene sequencing data of NR5A1 is stored in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRR22534035).

Abbreviations

- ACTH:

-

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AMH:

-

Anti-Müllerian hormone

- CNV-seq:

-

Copy number variation sequencing

- DBD:

-

DNA-binding domain

- DSD:

-

Disorders/Differences of sex development

- E2:

-

Estradiol

- EMSAs:

-

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

- ERT:

-

Estrogen-replacement therapy

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- HCG:

-

Human chorionic gonadotropin

- HMG:

-

Human menopausal gonadotropin

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- NR5A1:

-

Nuclear receptor subfamily 5 group A member 1

- 17-OHP:

-

17-Hydroxyprogesterone

- SRY:

-

Sex-determining region Y

- T:

-

Testosterone

- TRS:

-

Targeting specific disease‐causing genes

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

Lee PA, Nordenström A, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Auchus R, Baratz A, et al. Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions Approach and Care. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;85:158–80.

Elzaiat M, McElreavey K, Bashamboo A. Genetics of 46, XY gonadal dysgenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;36:101633.

Auchus RJ, Quint EH. Adolescents with Disorders of Sex Development (DSD)–Lost in Transition? Horm Metab Res. 2015;47(5):367–74.

Délot EC, Vilain E. Towards improved genetic diagnosis of human differences of sex development. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22:588–602.

Gomes NL, Batista RL, Nishi MY, Lerário AM, Silva TE, de Moraes NA, et al. Contribution of Clinical and Genetic Approaches for Diagnosing 209 Index Cases With 46, XY Differences of Sex Development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e1797–806.

Fabbri-Scallet H, de Sousa LM, Maciel-Guerra AT, Guerra-Júnior G, de Mello MP. Mutation update for the NR5A1 gene involved in DSD and infertility. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:58–68.

Rey RA. Next-generation sequencing as first-line diagnostic test in patients with disorders of sex development? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e2628–9.

Baxter RM, Arboleda VA, Lee H, Barseghyan H, Adam MP, Fechner PY, et al. Exome sequencing for the diagnosis of 46, XY disorders of sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E333–44.

Sepponen K, Lundin K, Yohannes DA, Vuoristo S, Balboa D, Poutanen M, et al. Steroidogenic factor 1 (NR5A1) induces multiple transcriptional changes during differentiation of human gonadal-like cells. Differentiation. 2022;S0301–4681:00062–7.

Globa E, Zelinska N, Shcherbak Y, Bignon-Topalovic J, Bashamboo A, McElreavey K. Disorders of sex development in a large Ukrainian cohort: clinical diversity and genetic findings. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:810782.

McElreavey K, Achermann JC. Steroidogenic Factor-1 (SF-1, NR5A1) and 46, XX Ovotesticular Disorders of Sex Development: One Factor Many Phenotypes. Horm Res Paediatr. 2017;87:189–90.

Ozisik G, Achermann JC, Jameson JL. The role of SF1 in adrenal and reproductive function: insight from naturally occurring mutations in humans. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:85–91.

Pedace L, Laino L, Preziosi N, Valentini MS, Scommegna S, Rapone AM, et al. Longitudinal hormonal evaluation in a patient with disorder of sexual development, 46, XY karyotype and one NR5A1 mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:2938–46.

Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R. Sex determination involves synergistic action of SRY and SF1 on a specific Sox9 enhancer [published correction appears in Nature. Nature. 2008;453:930–4.

Grinspon RP, Bedecarrás P, Ballerini MG, Iñiguez G, Rocha A, Mantovani Rodrigues Resende EA, et al. Early onset of primary hypogonadism revealed by serum anti-Müllerian hormone determination during infancy and childhood in trisomy 21. Int J Androl. 2011;34(415):e487-98.

Xuefeng J, Mo W, Xiaodong Z, Xuemei T, Xiaogang W, Daoqi Wu, et al. Serum Inhibin B’s Reference Range of 9 to 15 Year·Old M ale Children in Chongqing. J Pediatr Pharm. 2013;19(3):1–3.

Hong S, Wang L, Zhao D, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Tan J, et al. Clinical utility in infants with suspected monogenic conditions through next-generation sequencing. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7:e684.

Zhang D, Xin Y, Li MY, Meng LZ, Tong YJ. A novel missense mutation of NR5A1 c.46T>C (p.C16R) in a Chinese infant with ambiguous genitalia. Asian J Androl. 2022;24(4):438–40.

Vora KA, Srinivasan S. A guide to differences/disorders of sex development/intersex in children and adolescents. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49:417–22.

Costagliola G, Cosci O di Coscio M, Masini B, Baldinotti F, Caligo M, Tyutyusheva N, et al. Disorders of sexual development with XY karyotype and female phenotype: clinical findings and genetic background in a cohort from a single centre. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44:145–51.

Hughes LA, McKay-Bounford K, Webb EA, Dasani P, Clokie S, Chandran H, et al. Next generation sequencing (NGS) to improve the diagnosis and management of patients with disorders of sex development (DSD). Endocr Connect. 2019;8:100–10.

Achermann JC, Ozisik G, Ito M, Orun UA, Harmanci K, Gurakan B, et al. Gonadal determination and adrenal development are regulated by the orphan nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor-1, in a dose-dependent manner. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1829–33.

Pan S, Guo S, Liu L, Yang X, Liang H. Functional study of a novel c.630delG (p.Y211Tfs*85) mutation in NR5A1 gene in a Chinese boy with 46,XY disorders of sex development. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:477–86.

Yu BQ, Liu ZX, Gao YJ, Wang X, Mao JF, Nie M, et al. Prevalence of gene mutations in a Chinese 46, XY disorders of sex development cohort detected by targeted next-generation sequencing. Asian J Androl. 2021;23:69–73.

Yu B, Liu Z, Gao Y, Mao J, Wang X, Hao M, et al. Novel NR5A1 mutations found in Chinese patients with 46, XY disorders of sex development. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;89:613–20.

Alhamoudi KM, Alghamdi B, Aljomaiah A, Alswailem M, Al-Hindi H, Alzahrani AS. Case Report: Severe Gonadal Dysgenesis Causing 46, XY Disorder of Sex Development Due to a Novel NR5A1 Variant. Front Genet. 2022;13:885589.

Sudhakar DVS, Jaishankar S, Regur P, Kumar U, Singh R, Kabilan U, et al. Novel NR5A1 Pathogenic Variants Cause Phenotypic Heterogeneity in 46, XY Disorders of Sex Development. Sex Dev. 2019;13:178–86.

Berglund A, Johannsen TH, Stochholm K, Viuff MH, Fedder J, Main KM, et al. Incidence, prevalence, diagnostic delay, and clinical presentation of female 46, XY disorders of sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:4532–40.

Josso N, Rey RA. What Does AMH Tell Us in Pediatric Disorders of Sex Development? Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:619.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient and family for their kind participation.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z., D.J.W. and Y.X. planned the study. D.Z., D.J.W., Y.J.T. and M.Y.L. collected the clinical data. D.Z., L.Z.M. and Q.T.S. performed the functional study. D.Z. and D.J.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Y.X. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was initiated with the approval from the ethics committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (No. 2021PS115K) and written informed consent from the parents of the patient for providing a blood sample for genetic testing and publication of this case report. We can confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig 1.

Timeline of the diagnostic process for the patient.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig 2.

Conformational changes in the NR5A1 mutant. The residual at position 22 changes from a hydrophobic to hydrophilic amino acid with the G22C substitution; both the WT and NR5A1-Mut proteins show the formation of a hydrogen bond with Thr29.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig 3.

The raw figures of gels (EMSA) and the blots (Western blot) (A) the bands of the internal reference (β-actin). From left to right, these bands are non-transfected (Control, undeveloped band), transfected with an empty vector (Vector), Myc-tagged WT (WT), and c.64G>T (p. G22C) NR5A1-Mut (Mut) vectors; (B) NR5A1 expression in 293T cells according to western blot analysis. (same grouping as A); (C) ESMAs results showing altered DNA binding by the NR5A1 mutant (same group as A).

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table 1.

List of 360 endocrine-related genes detected by TRS.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 2.

Prediction of the impact of the c.64G>T (p.G22C) NR5A1 variant.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Wang, D., Tong, Y. et al. A novel c.64G > T (p.G22C) NR5A1 variant in a Chinese adolescent with 46,XY disorders of sex development: a case report. BMC Pediatr 23, 182 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-03974-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-03974-7