Abstract

Background and objective

Poor diets, characterized by excess fat, sugar and sodium intakes, are considered to be one of the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Diet patterns and intakes during adolescence may persist into adulthood and impact on risk for chronic disease later in life. We aimed to evaluate the dietary intake of obese adolescents and its relationship to cardiometabolic health including lipid status and glycemic control.

Methods and study design

This was a cross-sectional study of obese children aged 15 to < 18 years in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. All children had a medical history performed including a physical examination and fasting blood sample. Dietary intake was assessed using a semi-quantitative recall food frequency questionnaire. Multivariable linear regression model was performed to determine the relationship between dietary intakes and cardiovascular disease risks and to adjust for potential confounders.

Results

Of 179 adolescents, 101 (57.4%) were male and median age was 16.4 (15.0–17.9) years. The majority of adolescents (98%) had inadequate intake of fibre and exceeded intakes of total fat (65%) and total sugar (36%). There was statistically significant correlation found in the multivariable linear regression analysis between fibre intake and HDL cholesterol after adjusting for potential confounders (β = 0.165; p = 0.033).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that there is a high proportion of obese Indonesian adolescents with poor dietary intakes. There was relationship observed between intake of nutrients of concern (fibre) and cardiometabolic risk factor among this sample of obese adolescents. Future research should examine overall dietary patterns in more detail among this population to elucidate the role of poor diet intakes in development of cardiovascular disease risk factors in young people transitioning into adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a significant public health priority worldwide [1]. The prevalence of obesity is high and is reported to have increased in low- and middle-income countries including in Indonesia [2, 3]. After 5 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 1.9% in childhood to 3.2% in adolescence in a Yogyakarta city, Indonesia [2]. More than a decade in the same city in Indonesia, the prevalence of obesity among adolescents is doubling accounting for 7% [3]. The majority of obesity in adulthood originates in childhood and tracks into morbidity later in life [4]. It contributes to the development of risk factors for early cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, metabolic diseases, and atherosclerosis [5]. Identification of factors related to poor cardiometabolic health has been emphasized in children particularly in preventing modifiable risk factors.

It is considered that eating habits established in childhood and adolescence can persist into adulthood [6, 7]. A varied and balanced diet and the establishment of healthy eating habits will promote the health of young people throughout their lives [8]. Poor dietary intake, which is now considered as one of the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, is associated with the development of cardiovascular disease worldwide [8]. Therefore, early modification of eating habits, healthy dietary intake, and body weight can promote health and reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases later in life.

Studies on the association between dietary intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in children are limited. A previous systematic review of 11 studies conducted among Korean samples revealed that there were significant associations between obesity and dyslipidemia with excess intake of nutrients such as sodium, fat, and sugar. All studies focused on adults, but one was undertaken on children aged 9 to 10 years [9]. Another systematic review in adults evaluated the association between coronary heart disease and dietary factors including intake of vegetables, nuts, monounsaturated fatty acids, foods with a high glycemic index, trans–fatty acids, and overall diet quality and dietary patterns. This concluded that only a Mediterranean dietary pattern was causally protective against coronary heart disease [10].

Previous studies on associations between obesity and other cardiovascular disease risks and intake of fat and sugar and dietary fibre intake are conducted in high-income countries [9, 11, 12]. A recent published study evaluated fast food and soda pattern associated with significantly elevated insulin resistance among children and adolescents [11]. Children and adolescents in the high intake of fast food and soda pattern were associated with a higher waist circumference (β = 1.55), insulin level (β = 1.25), and body mass index (β = 0.53) and this was positively associated with HOMA-IR ≥ 2.6 (OR = 2.11; 95% CI: 1.227–3.638) (p < 0.05) compared with those in the lower intake of fast food and soda pattern [11]. A previous cross-sectional study was conducted in children evaluating the association between eating patterns and overweight status in children who participated in the Bogalusa Heart Study and found that several eating patterns including sweetened beverages, sweets, meats, and total consumption of low-quality foods were associated with overweight status with OR (95% CI) 1.33 (1.12–1.57), 1.21 (1.00–1.46), 1.38 (1.12–1.71) and 1.35 (1.08–1.68), respectively [12].

There is limited data from low-to-middle income countries, which are experiencing a nutrition transition and increasing prevalence of cardiovascular disease risks in children [13, 14]. Therefore, studies are needed to better identify the relationship between dietary intake and cardiovascular disease risks among obese adolescents. This study aimed to explore the relationship between excess intakes of nutrients of concern and cardiovascular disease risk factors among urban-dwelling adolescents in Indonesia. This is of importance to formulate an effective prevention strategy on dietary intake management for the development of cardiovascular diseases in obese adolescents in Indonesia as a model in low-to-middle income countries. We aimed to evaluate the dietary intake (sugar, fat, and fibre) of obese adolescents and its relationship to cardiovascular disease risk factors particularly impaired lipid profile (HDL and triglyceride) and glycemic control (HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose).

Materials and methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study of adolescents in Yogyakarta-Indonesia from February to October 2016. Screening for obesity was performed in seven public and three private high schools in the city [3]. Inclusion criteria were obese adolescents aged 15 to less than 18 years. Exclusion criteria was diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, renal diseases, cardiac diseases, any history of systemic disease or acute infections or history of current steroid use. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (KE/FK/0481/EC). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents/guardians of the children included in the study.

Data collection

All eligible children underwent an interview about their general health and medical history and physical examination and a fasting blood collection. We collected demographic data, histories of tobacco smoke exposure and daily physical activity using a structured questionnaire. Semi quantitative dietary recall was used to estimate the usual diet intake including the intake of carbohydrate, sugar, fibre, protein and fat [15]. The physical activity was measured using international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) (http://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/).

We performed a clinical examination, including body weight, height, and waist circumference. We measured the child’s weight using a portable weighing scale (CAMRY, EB9003). All children were weighed with light clothing without shoes or slippers. The weight was recorded as kilograms (kg) to the nearest 0.1 kg. We measured the height using a portable stadiometer or microtoise (GEA) with an erect position. The height was recorded in centimetres (cm) to the nearest of 0.5 cm. BMI was calculated based on weight in kg divided by height in metres squared. As previously described [14], to be considered obese, the adolescents must meet all three obesity criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) [16], the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [17], and the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) [18]. The conversion of BMI to z-score BMI was performed base on the WHO Growth Reference using WHO AnthroPlus (https://www.who.int/growthref/tools/en/). Waist circumference was measured using standardised procedures by placing tape between midway of the hip bone and the bottom of ribs and wrapping it around the child’s waist. Waist circumference for adolescent girl ≥ 80 cm and for boy ≥ 90 cm indicated abdominal obesity [19].

As previously described [3], blood pressure was reported by averaging three measurements after participants have been resting for 10 minutes in a sitting down position. We regularly calibrated the sphygmomanometers and used appropriate cuffs. The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents by The American Academy of Pediatrics 2017 has been used as a guideline to define elevated blood pressure, including hypertension. Elevated blood pressure is defined when systolic blood pressure is ≥120 mmHg, irrespective of diastolic blood pressure. This applies for adolescents aged ≥13 years [20].

A total of 10 ml blood was collected after overnight fasting to measure serum concentrations of triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, insulin, and hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c). Fasting plasma lipid profile was measured using enzymatic assays. Increased risk of diabetes and insulin resistance was assessed using HBA1c, fasting plasma glucose, fasting insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). Fasting plasma insulin was measured using immunoassay, while the fasting plasma glucose will be measured using the hexokinase method. HOMA-IR was calculated from fasting plasma glucose and insulin obtained [21].

Trained research assistants measured dietary intake using a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (SQ-FFQ) that has been previously used in obese adolescents in Indonesia [22]. Dietary questionnaires were analysed using NutriSurvey for Indonesian food database (EBISpro). We calculated a daily requirement intake among obese adolescents based on the recommended dietary allowance of Ministry of Health, Indonesia [23]. But dietary recommendations for children and adolescents from the American Heart Association (AHA) were established as a guide for both primordial and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease beginning at a young age [24]. For 14 to 18 years, the dietary recommendations differ between male and female adolescents. Further, we used a WHO guideline for maximum sugar intake (Table 1) [25].

Statistical analysis

Baseline data was described using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range or proportions as appropriate. Multivariable linear regression analysis was performed to determine the correlation between dietary intake (fibre, sugar and fat intakes) and the cardiometabolic risk factors (impaired lipid profile and glycemic control) and to adjust for potential confounders. Age, body mass index, gender, smoking status, physical activity and blood pressure were selected a priori as potential confounders. We conducted several multivariable linear regression models for each exposure-outcome association. Model 1 is the unadjusted correlation. In model 2, associations were adjusted for age and body mass index. Model 3 included adjustments for confounders as in model 2, and additional adjustments for gender. Model 4 included adjustments for confounders as in model 3, and additional adjustments for smoking status, physical activity score, and blood pressure. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. A p value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population and demographics

A total of 4268 students in seven public and three private high schools in Yogyakarta were screened, 298 (7%) of whom were classified as obese based on WHO, IOTF and CDC criteria. Blood samples were taken from 229 (76.8%) of those classified as obese. Therefore, we recruited 229 obese adolescents at public and private high schools in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Demographic characteristics were described in Table 2. Only 179 adolescents voluntarily completed a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (SQ-FFQ), and therefore were included in analyses of dietary intake (Table 2).

Dietary intake

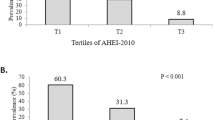

Table 3 illustrates daily energy requirement and percentage of energy to recommended dietary allowance among obese adolescents in Indonesia. Compared to dietary recommendations for children and adolescents from the American Heart Association and WHO guideline, 98% of participants had inadequate intake of fibre and 65% had excess intake of fat and excess sugar intake (36%) (Fig. 1).

Proportion (%) of obese adolescents’ who do not meet recommendations for energy and nutrient intakes relevant to cardiometabolic health (n = 179). Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents from the American Heart Association (AHA) were established as a guide for both primordial and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease beginning at a young age (Gidding et al., AHA 2005). WHO Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children (WHO March 2015). Energy (kJ) and (g) for other nutrients

Relationship between dietary intake and CVD risk factors

There was a statistically significant correlation between fibre intake and level of HDL cholesterol (β = 0.165; p = 0.033) in the multivariable linear regression analysis (Table 4). Further, we might found a correlation between sugar intake with HBA1c concentrations, but this was not statistically significant (β = 0.173; p = 0.055) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study explored the relationship of dietary intake and cardiovascular disease risks in 156 obese adolescents in Indonesia. This study demonstrates a high proportion of obese Indonesian adolescents with unhealthy diet. Fibre intake was correlated with the level of HDL cholesterol. Further, sugar intake might be correlated with risk of diabetes.

Obesity and cardiovascular disease are urgent public health priorities. Only a third of genetic influences play a role on the development of obesity. Majority of risk factors for developing obesity are modifiable; such as eating habits and sedentary behavior [26]. These modifiable risk factors can track from adolescence in adulthood and lead to cardiovascular disease in older age.

Suboptimal dietary intake comprises of high total fat, high total sugar, and low fibre intake. This present study demonstrated that unhealthy dietary intake among obese adolescents in Indonesia was prevalent demonstrating most of those consumed very low fibre, high total sugar, and high fat particularly saturated fatty acid. This dietary intake might lead to obesity and other obesity related cardiovascular diseases. Indeed, this study shows that low fibre intake significantly correlated with low HDL cholesterol in obese adolescents after adjusting for other potential confounding factors. While sugar intake might be positively correlated with levels of fasting glucose. High sugar and fat intakes may cause increased production of lipids, secretion of very low-density lipoproteins, accumulated fatty acids, and reduced oxidation that lead to atherosclerosis [27].

Fat is an essential source of energy, fatty acid, and fat-soluble vitamins. However, fat intake might cause dyslipidemia that led to the development of atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction [9]. Saturated fatty acid may result in increased cardiovascular disease, while polyunsaturated fatty acid contributes to decreased serum cholesterol and decreased incidence of coronary-artery disease [28]. Results of previous studies reveal that high fat intake contributing to increased LDL cholesterol and reduced HDL cholesterol [9]. In this study, we could not prove that fat intake correlated with cardiovascular disease risks. This might because of small sample size, so that the contradictory results are common.

High sugar intake is considered to be associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and high blood pressure [9, 29]. A previous study on dietary intake in Korean adults showed that consumption of high fat, sugar and low fibre associated with incidence of obesity [30]. High sugar intake positively correlated with risk of diabetes in this present study. This has a general agreement with previous study that high sugar intake associated with diabetes, obesity, and other cardiovascular risks [11, 31]. This present study also showed that high sugar intake did not correlated with the occurrence of insulin resistance. Our study corresponds to a study conducted among students aged 10 to 17 years in a developed country showing that intake of sugar and fibre was not associated with reduced in cardio-metabolic risk factors including hypertension and insulin resistance [31]. Further, in adult Chinese population, current non-smoking status, a diet rich in vegetables and fruits and high physical activity were independently associated with reduced risks of major coronary events and ischemic stroke [32]. Therefore, in this study we also made an effort to adjust for other factors that might be associated with the development of cardiovascular risks including smoking status and physical activities.

An unhealthy diet intake is strongly associated with cardiovascular diseases. Most obese adolescents in this study had low fibre intake (98%). This is comparable to the results of the Riskesdas surveys revealing that the majority of Indonesians (94%) did not consume an adequate amount of fruits and vegetables, which is five portions on seven continuous days [23].

Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents included an adequate amount of fibre, sugar, fat, other macro and micronutrients. These recommendations aim at achieving adequate nutrition for optimal growth and development. Malnutrition with an imbalanced intake of nutrients in terms of quality and quantity including macro and micronutrient can negatively affect child development and increase cardiovascular risk in later life [33]. Evidence on the association of dietary intake and cardiovascular disease risk among children are limited. Therefore, this present study might shine a light on enriching the researches on the correlation between dietary intake and cardiovascular disease risks in obese adolescents. Evidence arises from this study could contribute to the development of an effective strategy for preventing cardiovascular disease risks later in life.

There are some limitations of this study. First, this is cross-sectional study, so relationships described between exposure and outcome are not causal. There is also the possibility dietary intakes were underestimated by the FFQ methods. It is well documented that the methods used for dietary assessment are prone to recall bias. The responses of the obese adolescents may also be impacted by social desirability bias. Second, since this study was only performed in a city of Yogyakarta, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other obese adolescents in Indonesia. Third, since the sample size of this study was quite small, we might found insignificant relationship between diet and CVD risk factors.

This study shows that intake of unhealthy nutrients among obese adolescents in Yogyakarta, Indonesia might be prevalent. There was relationship observed between intake of nutrients of concern and cardiometabolic risk factors among this sample of obese adolescents. This study potentially provides a model for the correlation of dietary intake and obese-related disease in adolescents in a low- and middle-income country and broader strategies to prevent cardiovascular disease in adulthood. This study provides rationale for policy makers in Indonesia to consider obesity prevention and health promotion policies and programs targeting children and adolescents to prevent non-communicable disease burden in future.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin A1c

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- CDC:

-

the Centers for disease control and prevention

- IOTF:

-

the International obesity task force

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- SQ-FFQ:

-

A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire

- AHA:

-

American heart association

- RDA:

-

Recommended dietary allowance

- PUFA:

-

Poly-unsaturated fatty acid

- CHO:

-

Carbohydrate

References

Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR, et al. The global Syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the lancet commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8.

Julia M, van Weissenbruch MM, Prawirohartono EP, Surjono A, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Tracking for underweight, overweight and obesity from childhood to adolescence: a 5-year follow-up study in urban Indonesian children. Horm Res. 2008;69:301–6.

Murni IK, Sulistyoningrum DC, Susilowati R, Julia M. Risk of metabolic syndrome and early vascular markers for atherosclerosis in obese Indonesian adolescents. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2020;40(2):117–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/20469047.2019.1697568.

Venn AJ, Thomson RJ, Schmidt MD, Cleland VJ, Curry BA, Dwyer T, et al. Overweight and obesity from childhood to adulthood: a follow-up of participants in the 1985 Australian schools health and fitness survey. MJA. 2007;186:458–60. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00997.x.

Pencina MJ, Navar AM, Wojdyla D, Sanchez RJ, Khan I, Elassal J, et al. Quantifying importance of major risk factors for coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2019;139:1603–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031855.

Cruz F, Ramos E, Lopes C, Araújo J. Tracking of food and nutrient intake from adolescence into early adulthood. Nutrition. 2018;55-56:84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.02.015.

Winpenny EM, van Sluijs EMF, White M, Klepp K, Wold B, Lien N. Changes in diet through adolescence and early adulthood: longitudinal trajectories and association with key life transitions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0719-8.

GBD 2017 Diet collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8.

Kang YJ, Wang HW, Cheon SY, Lee HJ, Hwang KM, Yoon HS. Associations of obesity and dyslipidemia with intake of sodium, fat, and sugar among Koreans: a qualitative systematic review. Clin Nutr Res. 2016;5:290–304. https://doi.org/10.7762/cnr.2016.5.4.290.

Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):659–69. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.38.

Oh S, Lee SY, Kim DY, Woo S, Kim Y, Lee HJ, et al. Association of Dietary Patterns with weight status and metabolic risk factors among children and adolescents. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041153.

Nicklas TA, Yang S, Baranowski T, Zakeri I, Berenson G. Eating patterns and obesity in children the Bogalusa heart study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(1):9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00098-9.

Februhartanty J. Nutrition transition: what challenges are faced by Indonesia? Paper presented at the international public health seminar organized by Faculty of Public Health Universitas Sriwijaya; 2011.

Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:289–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.1.289.

Rockett HRH, Colditz GA. Assessing diets of children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(Suppl 1):1116S–22S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1116S.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–7. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.07.043497.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000 CDC Growth charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;series 11(246) Accessed 7 Aug 2018.

Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOFT) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:284–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x.

IDF. The IDF consensus definition of the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. 2007. Accessed 7 Aug 2018.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1904.

Kimm H, Lee SW, Lee HS, Shim KW, Cho CY, Yun JE, et al. Associations between lipid measures and metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and adiponectin – usefulness of lipid ratios in Korean men and women. Circ J. 2010;74:931–7. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0571.

Huriyati E, Luglio HF, Ratrikaningtyas PD, Tsani AF, Sadewa AH, Juffrie M. Dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and dietary fat intake in obese and normal weight adolescents: the role of uncoupling protein 2 -866G/A gene polymorphism. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2016;7(1):67–73 PMID: 27186330.

Ministry of Health. Angka kecukupan gizi yang dianjurkan untuk masyarakat Indonesia. Number 28. 2019.

Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, Daniels SR, Gillman MW, Lichtenstein AH, et al. American Heart Association; American Academy of Pediatrics. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners: consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2061–75. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169251.

WHO Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. 2015.

Garenc C, Vohl MC, Bouchard C, Perusse L. LIPE C-60G influences the effects of physical activity on body fat and plasma lipid concentrations: the Quebec family study. Hum Genomics. 2009;3:157–68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-7364-3-2-157.

Rauber F, Campagnolo PD, Hoffman DJ, Vitolo MR. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children's lipid profiles: a longitudinal study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:116–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.08.001.

Kromhout D. Dietary fats: long-term implications for health. Nutr Rev. 1992;50:49–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1992.tb01290.x.

Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;346:e7492. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e7492.

Kim J, Jo I, Joung H. A rice-based traditional dietary pattern is associated with obesity in Korean adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:246–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.10.005.

Setayeshgar S, Ekwaru JP, Maximova K, Majumdar SR, Storey KE, Veugelers PJ, et al. Dietary intake and prospective changes in cardiometabolic risk factors in children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0215.

Lv J, Yu C, Guo Y, Bian Z, Yang L, Li L, et al. Adherence to healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1116–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.076.

Murni IK, Sulistyoningrum DC, Oktaria V. Association of vitamin D deficiency with cardiovascular disease risk in children: implications for the Asia Pacific region. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25(Suppl 1):S8–19. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.122016.s1.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Rasita Amalia for her contribution during the data collection and data entry. We also acknowledge Erik C Hookom for providing editorial assistance.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IKM contributed to conception and design, performing clinical work and data collection, data analysis and interpretation, preparation of draft manuscript, revision, and overall scientific management. DCS contributed to conception and design, doing clinical and data collection, data analysis and interpretation, preparation of draft manuscript, doing revision, and overall scientific management. RS contributed to conception and design, data interpretation, manuscript review. MJ contributed to conception and design, doing clinical and data collection, data analysis and interpretation, preparation of draft manuscript, revision, and overall scientific management. KD contributed to data analysis and interpretation, preparation of draft manuscript and manuscript revision. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (KE/FK/0481/EC). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents/guardians of participants included in the study.

All the experiment protocol for involving humans was in accordance to guidelines of national/international/institutional or Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Supplementary table 1.

The criteria of obese based on WHO, CDC, and IOTF references.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Murni, I.K., Sulistyoningrum, D.C., Susilowati, R. et al. The association between dietary intake and cardiometabolic risk factors among obese adolescents in Indonesia. BMC Pediatr 22, 273 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03341-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03341-y