Abstract

Background

Studies assessing the association between short birth interval, a birth-to-birth interval of less than 33 months, and under-five undernutrition have produced inconclusive results. This study aimed to assess the relationship between short birth interval and outcomes of stunting, underweight, and wasting among children aged under-five in Ethiopia, and potential mediation of any associations by maternal anemia and baby birth size.

Method

Data from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) was used. Stunting, wasting, and underweight among children aged under-five were outcome variables. Generalized Structural Equation Modeling (GSEM) was used to examine associations between short birth interval and outcomes, and to assess hypothesized mediation by maternal anemia and baby birth size.

Results

Significant associations between short birth interval and stunting (AOR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.35, 1.66) and underweight (AOR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.28, 1.61) were found. There was no observed association between short birth interval and wasting (AOR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.90, 1.23). Maternal anemia and baby birth size had a significant partial mediation effect on the association between short birth interval and stunting (the coefficient reduced from β = 0.337, p < 0.001 to β = 0.286, p < 0.001) and underweight (the coefficient reduced from β = 0.449, p < 0.001 to β = 0.338, p < 0.001). Maternal anemia and baby birth size mediated 4.2% and 4.6% of the total effect of short birth interval on stunting and underweight, respectively.

Conclusion

Maternal anemia and baby birth size were identified as mediators of the association between short birth interval and under-five undernutrition status. Policies and programs targeting the reduction of under-five undernutrition should integrate strategies to reduce maternal anemia and small baby birth size in addition to short birth interval.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation, short birth interval is defined as a birth-to-birth interval of less than 33 months [1]. Short birth interval is more common among women in low- and middle-income countries [2] and Ethiopia has an estimated prevalence of 45.8% [3]. The determinants of short birth interval in Ethiopia, such as maternal occupation, wealth index, and regions, have been documented elsewhere [3]. Our previous studies [4, 5] also have documented the hotspot areas [4] and socioeconomic inequality [5] of short birth interval in Ethiopia.

Some of the adverse child health outcomes associated with short birth intervals are preterm birth [6, 7] low birth weight [6, 7] small size for gestational age [6] congenital anomalies [8, 9], and autism [10]. Similarly, miscarriage, preeclampsia, and premature rupture of membranes [11, 12], and maternal anemia [13, 14] are among the poor maternal health outcomes associated with short birth interval.

Previous studies assessing associations between short birth interval and under-5 child undernutrition have been inconclusive. Undernutrition, in our study, refers to stunting (short-for-age), underweight (thin-for-age), and wasting (thin-for-height) [15]. Some previous literature has documented the significant association between short birth interval and stunting [16,17,18], wasting [19], and underweight [20]. Other studies have found no significant associations reported between short birth interval and stunting [21, 22] and underweight [23]. In the previous studies [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], short birth interval was not defined according to the WHO recommendation, which is less than 33 months [1]. The limitation of some of the above-mentioned studies [18, 20, 21, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] was that they did not use nationally representative data. Alternatively, several studies [24,25,26,27,28, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] that have investigated determinants of undernutrition among children in Ethiopia did not consider short birth interval as a potential causal factor.

Other limitation of previous work is the inclusion of maternal anemia [16, 19] and baby birth size [19, 22] as confounders in estimating the association between short birth interval and child malnutrition. However, these factors are likely to lie on the causal pathway between short birth interval and undernutrition outcomes and are thus more likely to be mediators than confounders. That is, maternal anemia [13, 14] and baby birth size [6, 7] are health outcomes that can result from short birth interval (i.e., mediators), rather than being causes of short birth interval and child undernutrition (i.e., confounders). By definition, a confounder is a variable that has a direct causal effect on the main exposure variable and the outcome of interest [44, 45]. A mediator is intervening variables that lie along the causal pathway between the exposure/intervention and the outcome of interest [46]. Adjustment of mediators as confounders will under-estimate the causal effect of the variable of interest (short birth interval in this case) on the outcome variable (stunting, wasting, and underweight in this case) and may reduce the ability to identify the total causal effect of interest [45, 47]. The policy and program implication of investigating the mediation effect of maternal anemia and baby size is its ability to identify targets for interventions to prevent the development of child undernutrition.

Africa and Asia bear the greatest share of all forms of malnutrition [48, 49]. In Ethiopia, 38.0% of under-five children are stunted, 24% are underweight, and 10% are wasted [15]. One-fourth of child deaths in Ethiopia are associated with malnutrition [50]. As a result, the Ethiopian government developed the Seqota Declaration aiming to end malnutrition, particularly stunting, by 2030 [51, 52]. It is also known that one of the 2030 agendas for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is linked with ending all forms of malnutrition (i.e., SDG 2, target 2.1.1) [53, 54]. Nevertheless, undernutrition among children remains an urgent concern in Ethiopia [55], requiring the identification of its multifactorial predictors to make an informed decision and meet the above-mentioned goals [51,52,53].

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the mediation effect of maternal anemia and baby birth size in the association between short birth interval and under-five undernutrition (i.e., the direct and indirect causal pathway). This study aimed to assess the mediation effect of maternal anemia and baby birth size in the association between short birth interval and under-five malnutrition; stunting, underweight, and wasting. The findings of this study will help policy makers and program planners consider the effect of short birth interval and potential mediators in combating undernutrition in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data source, design, and sample size

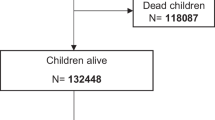

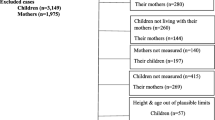

Data from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) were used in this study. The EDHS is a nationally representative survey in Ethiopia and has been conducted every 5 years since 2000. The 2016 EDHS collected data on the nutritional status of children by measuring the weight and height of children under age 5 in all sampled households and comparing these to international standards [15]. Weight was measured with an electronic mother-infant scale (SECA 878 flat) designed for mobile use. Height was measured with a measuring board (Shorr Board®). Children younger than age 24 months were measured lying down on the board (recumbent length) while standing height was measured for the older children. Children’s height/length, weight, and age data were used to calculate three indices: height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age. The DHS data were compared to the NCHS/CDC/WHO international reference standards for height-for-age, weight-for-age, and weight-for-height. Further information regarding the survey methodologies and measurement of nutritional status is presented in the full EDHS report [15]. Since short birth interval was the main exposure variable, the current study included women who had reported at least two live births during the five years preceding the survey. Accordingly, 7,090 women were included for analyses of stunting, 7,154 for wasting, and 7,233 for underweight. Respondents with missing data for height-for-age (\(n\)=1,358), weight-for-height (\(n\)= 1,294), and weight-for-age (\(n\)= 1,215) of their child were excluded from the analysis.

Measurement and variables

Outcome variables

Under-five undernutrition represented by stunting (a height-for-age Z-score below minus two standard deviations (-2 SD) from the median of the reference population), wasting (a weight-for-height Z-score below minus two standard deviations (-2 SD) from the median of the reference population), and underweight (a weight-for-age Z-score below minus two standard deviations (-2 SD) from the median of the reference population) were the outcome variables [15].

Exposure variables

Short birth interval, defined as a birth-to-birth interval of less than 33 months [1], was the exposure variable in this study. Women’s birth interval data were collected by extracting dates of birth for their biological children from the children’s birth/immunization certificate, and/or asking the mother to provide dates of birth for their children. When both sources of data were available, the accuracy of documenting dates of birth in birth/immunization certificates was cross-checked with the information provided by mothers. This resolved discrepancies such as the documented birth date representing the date when the birth was recorded, rather than the actual birth date. When children’s birth/immunization certificates were not available, information regarding children’s date of birth was obtained from their mothers. The EDHS presented birth interval data in months. Detailed description regarding birth interval data collection is also provided elsewhere [4, 56].

Mediators

Maternal anemia and birth size were the two sequential mediators considered in this analysis. Women’s blood samples were drawn from a drop of blood taken from a finger prick and collected in a microcuvette. Hemoglobin analysis was carried out on-site using a battery-operated portable HemoCue analyser [15, 57, 58]. The hemoglobin level was adjusted for cigarette smoking and altitude in enumeration areas above 1,000 m. Anemia was defined as per the WHO recommendation, which is hemoglobin level less than 12.0 g/deciliter for pregnant women and 11 g/deciliter for non pregnant women [15, 59, 60]. In the 2016 EDHS, information on birth weight was collected by either a written record or maternal estimation. The current study used maternal estimated baby birth size as a proxy indicator for birth weight. All mothers who had given birth during the five years preceding the survey were asked to retrospectively classify their babies’ sizes at birth as ‘very large’, ‘larger than average’, ‘average’, ‘smaller than average’ or ‘very small’. This estimate was used because objectively measured birth weight data were not available for most (86%) newborns in Ethiopia [15]. Implications of this are discussed further in the Discussion section. The maternal estimated baby birth size was thus the only means of measuring birth size for the 86% of newborns with unknown birth weight, in a manner consistent with that of children (14%) whose birth weight was collected in the 2016 EDHS. In the current study, a baby’s birth size was coded as a binary variable. Very large, larger than average, and average responses were coded as ‘average or above average, and smaller than average and very small responses were coded as ‘small’.

Covariates

Maternal age, maternal education (no formal education, primary, secondary +), maternal occupation (not working, working), household wealth (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), place of residence (urban/rural), region (Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Somalia, Benishangul-Gumuz, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region [SNNPR], Gambella, Harari, Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa), and total children ever born (1–2, 3–4, 5 +) were considered as potential covariates (see Table 1). These covariates were selected after reviewing relevant literature [3, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency with percent) were computed to describe the outcome (stunting, wasting, and underweight) by the respondents’ characteristics. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to assess differences in stunting, wasting, and underweight frequencies by respondents’ characteristics. Sampling weight was considered to adjust for the non-proportional allocation of the sample to different regions, to their urban and rural areas, and the possible differences in response rates. Details about the weighting procedure can be found in the EDHS report [15]. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent association between short birth interval and stunting, wasting, and underweight. Variables listed under the covariates above were included as potential confounders. Short birth interval showing a significant association with outcomes at a p-value of < 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression analysis were considered to test whether the hypothesized mediators (maternal anemia and baby birth size) mediated the observed relationships using mediation analysis. This is because, first, there has to be a significant association between the main exposure variable (short birth interval in this case) and outcomes (i.e., stunting, underweight, and wasting in this case) to be mediated to further examine for the mediation effect of the potential mediators (maternal anemia and baby birth size in this case) [61]. Then, Generalized Structural Equation Modeling (GSEM) was used to test the mediation effect of the potential sequential mediators (i.e., maternal anemia and baby birth size) on under-five undernutrition. The mediation analysis was performed using Stata ‘gsem’ command. First, the initial path models were fitted using exposure variable (i.e., short birth interval), potential mediators (i.e., maternal anemia and baby birth size), and the outcomes (i.e., stunting, wasting, and underweight, each separately). This was done to assess crude associations between the above-mentioned variables. Second, after controlling for potential confounders, the full mediation analysis models were fitted for each child undernutrition outcome separately. Each outcome variable was a binary variable analyzed assuming a Bernoulli response distribution and logit link function. Mediation can be either complete or partial [44, 62,63,64]. In complete mediation, the entire (or total) effect of an exposure variable (i.e., short birth interval) on an outcome variable (i.e., stunting, wasting, and underweight) is transmitted through one or more mediators (i.e., maternal anemia and baby birth size in this case). Thus, the exposure variable has no direct effect on the outcome variables; its entire effect is indirect. In partial mediation, an exposure variable has both direct and indirect effects on the outcome variables. The direct effect is not mediated, whereas the indirect effect is transmitted through one or more mediator variables. Mediators can also be classified as single and multiple (and sequential) [62, 65]. A single mediator is considered when there is only one variable in the causal pathway between exposure and outcome variable. Multiple mediators refer to when more than one mediator variables operate jointly at the same stage in a causal model. Thus, there will be several indirect effects linking the exposure variable to the outcome variable. When the indirect effect of an exposure variable on the outcome variable operates through a chain of mediator variables, it refers to sequential mediators. For instance, maternal anemia and baby birth size, in the current study, could be considered as the sequential mediators. In this analysis, the indirect effects were estimated using the product-of-coefficients test [66, 67]. For a variable with missing data such as maternal anemia, a complete case analysis was performed with the assumption of missing completely at random. Stata ‘nlcom’ command was used to estimate the direct, indirect, total effects of short birth interval on child malnutrition. A p-value of < 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 14 statistical software (StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. 2015).

Results

Participant characteristics

The majority of stunting (78.1%), wasting (78.3%), and underweight (81.5%) were documented among children of women with no formal education. Similarly, 72.1% of stunting, 72.2% of wasting, and 73.9% of underweight were experienced by children of unemployed women. The prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight were higher (> 90.0% for each) among rural residents. About half of stunting, wasting, and underweight were among children born after a short birth interval (Table 1).

The association between short birth interval and under-five undernutrition status

After conditioning on the potential confounders, significant associations between short birth interval and stunting (AOR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.35, 1.66) and underweight (AOR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.28, 1.61) were found. There was no significant association between short birth interval and wasting (AOR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.90, 1.23) (Table 2).

Mediation analysis

Table 3 and Fig. 1a and b illustrate findings from the mediation analysis. Short birth interval was significantly associated with stunting (path d, β = 0.337, p < 0.001). Significant associations were also found between short birth interval and maternal anemia (path a, β = 0.368, p < 0.001), maternal anemia and baby birth size (path b, β = 0.124, p = 0.001), and baby birth size and stunting (path c, β = 0.258, p < 0.001). After conditioning on maternal anemia and baby birth size, the coefficient for short birth interval reduced in magnitude from path d, β = 0.337, p < 0.001 to path d’, β = 0.286, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1a). This finding indicated that the effect of short birth interval on stunting was partially mediated by maternal anemia and baby birth size. The sequential mediators, maternal anemia and baby birth size, mediated 4.2% of the total effect of short birth interval on stunting.

There was a significant association between short birth interval and underweight (path d, β = 0.449, p < 0.001). Significant associations were also found between short birth interval and maternal anemia (path a, β = 0.360, p < 0.001), maternal anemia and baby birth size (path b, β = 0.115, p = 0.003), and baby birth size and underweight (path c, β = 0.399, p < 0.001). After conditioning on maternal anemia and baby birth size, the coefficient for short birth interval reduced in magnitude from path d, β = 0.449, p < 0.001 to path d’, β = 0.338, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1b). This reduction in the magnitude of the coefficient illustrated that maternal anemia and baby birth size partially mediated the association between short birth interval and underweight. Maternal anemia and baby birth size mediated 4.6% of the total effect of short birth interval on underweight.

Since there was no significant association to be mediated between short birth interval and wasting (AOR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.90, 1.23; as presented in Table 2), the mediation effect of maternal anemia and baby birth size was not assessed.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the relationship between short birth interval and stunting, underweight, and wasting among children aged under-five in Ethiopia, and potential mediation of any associations by maternal anemia and baby birth size. To our knowledge, no study, to date, has examined the mediation effect of maternal anemia and baby birth size on the association between short birth interval and under-five undernutrition. The study showed significant associations between short birth interval and stunting and underweight. Maternal anemia and baby birth size had significant partial mediation effects on the relationship between short birth interval and stunting and underweight. The evidence from this study will help policy makers and program planners design a multifaceted approach to reduce child undernutrition in Ethiopia.

Our study showed short birth interval was associated with stunting and underweight. Previous studies also reported similar findings regarding the association between short birth interval and stunting [16,17,18, 68] and underweight [20, 68, 69]. The associations between short birth interval and stunting and underweight could be attributed to the increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation [70], inappropriate complementary feeding [71], poor dietary diversity [72, 73], and inadequate minimum meal frequency [74] associated with short birth interval. Moreover, from a women's perspective, the perception of being undernourished by women with a short birth interval may influence their infant feeding choices, such as the duration and frequency of breastfeeding [70]. These choices could then influence the child’s nutritional status via direct effects attributable to nutrient intake and indirect effects attributable to morbidity.

The current study illustrated that maternal anemia and baby birth size mediated the association between short birth interval and stunting as well as underweight. The most common hypothesis for adverse maternal and child outcomes, such as undernutrition, secondary to short birth interval is maternal folate depletion [75, 76]. This hypothesis posits that a short birth interval gives women insufficient time to recover from folate requirements during pregnancy [77]. It is known that folate depletion can expose women to anemia, resulting from ineffective erythropoiesis [78]. Subsequently, maternal anemia could result in low birth weight [79,80,81]. Finally, low birth weight, in turn, could affect the development of stunting [21, 82,83,84] as well as underweight [84, 85] among children. This finding could imply the need to prevent a short birth interval as well as maternal anemia to prevent low baby birth size and their associated undernutrition.

In this study, short birth interval was not significantly associated with wasting. This finding is not consistent with the finding of a previous study conducted in Ethiopia [19], where a significant association between short birth interval and wasting was reported. The discrepancy could be due to the difference, first, in the study population where the previous study [19] included women who had given birth once. These women were not eligible to provide birth interval information and the result could have been different if they were excluded from the study. Including the above-mentioned non-eligible women may also obscure the true effect of birth interval on wasting. Second, unlike the current study, the categorization of birth interval data (i.e., first birth, < 24 months, 24–47 months, and ≥ 48 months) in the previous study [19] was not according to the WHO recommendation [1].

The key strength of our study was the application of GSEM, a robust statistical technique, to assess the mediation effect of maternal anemia and baby birth size in the association between short birth interval and child undernutrition. Using data from a large sample size and nationally representative survey are also another strength of the current study. This study has also a few limitations. First, the use of observational data may limit the establishment of a causal association between short birth interval, mediators, and undernutrition status of under-five children. Second, although studies [86, 87] from developing countries recommended the use of baby birth size as a proxy for birth weight, it should be considered with precaution while interpreting the findings of this study. This is because it could be influenced by societal and contextual factors. Our study, however, considered maternal and contextual characteristics, such as educational level, wealth status, place of residence, region, and other variables detailed under the covariates section, as a potential confounder in its analysis. In the 2016 EDHS, 28% of births were delivered by a skilled provider, and information on birth weight was obtained for only 14% of births [15]. In contrast, information on baby birth size was collected for all children included in the survey. Hence, our study used maternal estimated baby birth size as a proxy indicator of birth weight. Under some circumstances, such as in the absence of children’s birth/immunization certificates and inconsistency in information regarding children’s date of birth between the one documented in the above-mentioned certificates and those obtained from the maternal response, information regarding children’s date of birth was obtained from their mothers. This information may be prone to recall bias. The timing of occurrence of maternal anemia should also be carefully considered while interpreting the findings of the study.

Conclusion

There were statistically significant associations between short birth interval and stunting and underweight. This study also revealed that the association between short birth interval and stunting and underweight were partially mediated by the sequential mediators; maternal anemia and baby birth size. Policies and programs targeting the reduction of under-five undernutrition (stunting and underweight) should integrate strategies to reduce maternal anemia and small baby birth size in addition to the short birth interval. Health care providers should create awareness of the adverse effect of short birth interval on children's nutritional status. We also recommend women space births at least 33 months. Expanding postpartum contraception could help women prevent short birth interval. Longitudinal data is required to better estimate the causal effect of short birth interval and its associated mediators on child undernutrition.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset is available from The DHS Program repository at the following link: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Ethiopia_Standard-DHS_2016.cfm?flag=0.

References

World Health Organization. Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Ajayi AI, Somefun OD. Patterns and determinants of short and long birth intervals among women in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Med. 2020;99:19(e20118).

Shifti DM, Chojenta C, G. Holliday E, Loxton D. Individual and community level determinants of short birth interval in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. PloS one. 2020;15(1):e0227798.

Shifti DM, Chojenta C, Holliday EG, Loxton D. Application of geographically weighted regression analysis to assess predictors of short birth interval hot spots in Ethiopia. PloS one. 2020;15(5):e0233790.

Shifti DM, Chojenta C, Holliday EG, Loxton D. Socioeconomic inequality in short birth interval in Ethiopia: a decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–13.

Grisaru-Granovsky S, Gordon E-S, Haklai Z, Samueloff A, Schimmel MM. Effect of interpregnancy interval on adverse perinatal outcomes—a national study. Contraception. 2009;80(6):512–8.

Adam I, Ismail MH, Nasr AM, Prins MH, Smits LJ. Low birth weight, preterm birth and short interpregnancy interval in Sudan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(11):1068–71.

Chen I, Jhangri GS, Chandra S. Relationship between interpregnancy interval and congenital anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(6):564-e561-568.

Kwon S, Lazo-Escalante M, Villaran M, Li C. Relationship between interpregnancy interval and birth defects in Washington State. J Perinatol. 2012;32(1):45.

Cheslack-Postava K, Liu K, Bearman PS. Closely spaced pregnancies are associated with increased odds of autism in California sibling births. Pediatrics. 2011;127:246–53.

DaVanzo J, Razzaque A, Rahman M, Hale L, Ahmed K, Khan MA, Mustafa G, Gausia K. The effects of birth spacing on infant and child mortality, pregnancy outcomes, and maternal morbidity and mortality in Matlab. Bangladesh: Technical Consultation and Review of the Scientific Evidence for Birth Spacing; 2004.

DaVanzo J, Hale L, Razzaque A, Rahman M. Effects of interpregnancy interval and outcome of the preceding pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in Matlab, Bangladesh. BJOG: An Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;114(9):1079–87.

Lilungulu A, Matovelo D, Kihunrwa A, Gumodoka B. Spectrum of maternal and perinatal outcomes among parturient women with preceding short inter-pregnancy interval at Bugando Medical Centre, Tanzania. Maternal health, neonatology and perinatology. 2015;1(1):1–7.

Abay A, Yalew HW, Tariku A, Gebeye E. Determinants of prenatal anemia in Ethiopia. Archives of Public Health. 2017;75(1):1–10.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Haile D, Azage M, Mola T, Rainey R. Exploring spatial variations and factors associated with childhood stunting in Ethiopia: spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):49.

Takele K, Zewotir T, Ndanguza D. Understanding correlates of child stunting in Ethiopia using generalized linear mixed models. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–8.

Kahssay M, Woldu E, Gebre A, Reddy S. Determinants of stunting among children aged 6 to 59 months in pastoral community, Afar region, North East Ethiopia: unmatched case control study. BMC nutrition. 2020;6(1):1–8.

Dessie ZB, Fentie M, Abebe Z, Ayele TA, Muchie KF. Maternal characteristics and nutritional status among 6–59 months of children in Ethiopia: further analysis of demographic and health survey. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):1–10.

Hintsa S, Gereziher K. Determinants of underweight among 6–59 months old children in Berahle, Afar, North East Ethiopia: a case control study 2016. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–8.

Abeway S, Gebremichael B, Murugan R, Assefa M, Adinew YM. Stunting and its determinants among children aged 6–59 months in northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Nut Metab. 2018;2018.

Gebru KF, Haileselassie WM, Temesgen AH, Seid AO, Mulugeta BA. Determinants of stunting among under-five children in Ethiopia: a multilevel mixed-effects analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Fenta HM, Tesfaw LM, Derebe MA. Trends and determinants of underweight among under-five children in Ethiopia: data from EDHS. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020.

Geberselassie SB, Abebe SM, Melsew YA, Mutuku SM, Wassie MM. Prevalence of stunting and its associated factors among children 6–59 months of age in Libo-Kemekem district, Northwest Ethiopia; a community based cross sectional study. PloS one. 2018;13(5):e0195361.

Dake SK, Solomon FB, Bobe TM, Tekle HA, Tufa EG. Predictors of stunting among children 6–59 months of age in Sodo Zuria District, South Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC nutrition. 2019;5(1):1–7.

Nigatu G, Woreta SA, Akalu TY, Yenit MK. Prevalence and associated factors of underweight among children 6–59 months of age in Takusa district, Northwest Ethiopia. International journal for equity in health. 2018;17(1):1–8.

Gamecha R, Demissie T, Admasie A. The magnitude of nutritional underweight and associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in Wonsho Woreda, Sidama Zone Southern Ethiopia. The Open Public Health Journal. 2017;10:7–16.

Tibebu NS, Emiru TD, Tiruneh CM, Getu BD, Azanaw KA. Underweight and Its Associated Factors Among Children 6–59 Months of Age in Debre Tabor Town, Amhara Region of Ethiopia, 2019: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2020;11:469.

Liben ML, Abuhay T, Haile Y. Determinants of child malnutrition among agro pastorals in northeastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Health Sci J. 2016;10(4):1.

Agedew E, Shimeles A. Acute undernutrition (wasting) and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Kemba Woreda, southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Int J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2016;2(2):59–66.

Tsedeke W, Tefera B, Debebe M. Prevalence of acute malnutrition (wasting) and associated factors among preschool children aged 36–60 months at Hawassa Zuria, South Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. J Nutr Food Sci. 2016;6(466):2.

Woldeamanuel BT, Tesfaye TT. Risk factors associated with under-five stunting, wasting, and underweight based on Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey datasets in Tigray region, Ethiopia. J Nut Metab. 2019;2019.

Kassie GW, Workie DL. Determinants of under-nutrition among children under five years of age in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–11.

Mulugeta A, Hagos F, Kruseman G, Linderhof V, Stoecker B, Abraha Z, Yohannes M, Samuel GG. Child malnutrition in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2010;87(6):248–54.

Kassa ZY, Behailu T, Mekonnen A, Teshome M, Yeshitila S. Malnutrition and associated factors among under five children (6–59 Months) at Shashemene Referral Hospital, West Arsi Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Curr Pediatr Res. 2017;21(1):172–80.

Zeray A, Kibret GD, Leshargie CT. Prevalence and associated factors of undernutrition among under-five children from model and non-model households in east Gojjam zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC nutrition. 2019;5(1):1–10.

Wolde T, Adeba E, Sufa A. Prevalence of chronic malnutrition (stunting) and determinant factors among children aged 0–23 months in Western Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Nutritional Disorders & Therapy. 2014;4(4):148–54.

Amare D, Negesse A, Tsegaye B, Assefa B, Ayenie B. Prevalence of undernutrition and its associated factors among children below five years of age in Bure Town, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Northwest Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2016;2016.

Berhanu G, Mekonnen S, Sisay M. Prevalence of stunting and associated factors among preschool children: a community based comparative cross sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC nutrition. 2018;4(1):1–15.

Ma’alin A, Birhanu D, Melaku S, Tolossa D, Mohammed Y, Gebremicheal K. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6–59 months of age in Shinille Woreda, Ethiopian Somali regional state: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutrition. 2016;2(1):1–12.

Mengesha HG, Vatanparast H, Feng C, Petrucka P. Modeling the predictors of stunting in Ethiopia: analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey data (EDHS). BMC nutrition. 2020;6(1):1–11.

Mengesha Kassie A, Beletew Abate B, Wudu Kassaw M, Gebremeskel Mesafint T: Prevalence of underweight and its associated factors among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia: analysis of the. Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey Data. J Environ Public Health. 2016;2020:2020.

Tusa BS, Weldesenbet AB, Kebede SA. Spatial distribution and associated factors of underweight in Ethiopia: An analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health survey, 2016. Plos one. 2020;15(12):e0242744.

MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1(4):173–81.

Zhang Z. Distinguishing between mediators and confounders is important for the causal inference in observational studies. AME Med J. 2019;4:35.

Field-Fote E. Mediators and moderators, confounders and covariates: Exploring the variables that illuminate or obscure the “active ingredients” in neurorehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2019;43(2):83–4.

Richiardi L, Bellocco R, Zugna D. Mediation analysis in epidemiology: methods, interpretation and bias. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(5):1511–9.

World Health Organization. UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2020 edition. 2020.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2020 edition of the joint child malnutrition estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

For every child, Nutrition https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/nutrition

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. National Nutrition Program 2016–2020. 2015.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Seqota Declaration Innovation Phase Investment Plan 2017 – 2020 January 2018.

UN: Transforming our World. The 2030 Agenda For Sustainable Development Goal (A/RES/70/1). 2015.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, National Plan Commission. Ethiopia 2017 Voluntary National Review on SDGs: Government Commitments, National Ownership and Performance Trends. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa; 2017.

Amaha ND. Ethiopian progress towards achieving the global nutrition targets of 2025: analysis of sub-national trends and progress inequalities. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):1–5.

ICF International. Demographic and Health Survey Interviewer’s Manual. MEASURE DHS Basic Documentation No. 2. Calverton, Maryland, U.S.A.: ICF International; 2012.

Sanchis-Gomar F, Cortell-Ballester J, Pareja-Galeano H, Banfi G, Lippi G. Hemoglobin point-of-care testing: the HemoCue system. J Lab Autom. 2013;18(3):198–205.

Jaggernath M, Naicker R, Madurai S, Brockman MA. Ndung’u T, Gelderblom HC: Diagnostic accuracy of the HemoCue HB 301, STAT-Site MHgb and URIT-12 point-of-care hemoglobin meters in a central laboratory and a community based clinic in Durban, South Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152184.

World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. In.: World Health Organization; 2011.

Kinyoki D, Osgood-Zimmerman AE, Bhattacharjee NV, Kassebaum NJ, Hay SI: Anemia prevalence in women of reproductive age in low-and middle-income countries between,. and 2018. Nat Med. 2000;2021:1–22.

Jung SJ. Introduction to Mediation Analysis and Examples of Its Application to Real-world Data. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021;54(3):166.

MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614.

Fairchild AJ, McDaniel HL. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: mediation analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1259–71.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173.

VanderWeele T, Vansteelandt S. Mediation analysis with multiple mediators. Epidemiologic methods. 2014;2(1):95–115.

Winship C, Mare RD. Structural equations and path analysis for discrete data. Am J Sociol. 1983;89(1):54–110.

Chen L-J, Hung H-C. The indirect effect in multiple mediators model by structural equation modeling. European Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy. 2016;4(3):36–43.

Chungkham HS, Sahoo H, Marbaniang SP. Birth interval and childhood undernutrition: Evidence from a large scale survey in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2020;8(4):1189–94.

Nojouni M, Tehrani A, Najmabadi S. Risk analysis of growth failure in under-5-year children. Arch Iranian Med. 2004;7(3):195–200.

Dewey KG, Cohen RJ. Does birth spacing affect maternal or child nutritional status? A systematic literature review. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3(3):151–73.

Epheson B, Birhanu Z, Tamiru D, Feyissa GT. Complementary feeding practices and associated factors in Damot Weydie District, Welayta zone. South Ethiopia BMC public health. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Sema A, Belay Y, Solomon Y, Desalew A, Misganaw A, Menberu T, Sintayehu Y, Getachew Y, Guta A, Tadesse D. Minimum Dietary Diversity Practice and Associated Factors among Children Aged 6 to 23 Months in Dire Dawa City, Eastern Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Global Pediatric Health. 2021;8:2333794X21996630.

Harvey CM, Newell M-L, Padmadas SS. Socio-economic differentials in minimum dietary diversity among young children in South-East Asia: evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(16):3048–57.

Tessema M, Belachew T, Ersino G. Feeding patterns and stunting during early childhood in rural communities of Sidama, South Ethiopia. Pan African Med J. 2013;14:75.

Miller JE. Birth intervals and perinatal health: an investigation of three hypotheses. Fam Plann Perspect. 1991;23(2):62–70.

Winkvist A, Rasmussen KM, Habicht J-P. A new definition of maternal depletion syndrome. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(5):691–4.

King JC. The risk of maternal nutritional depletion and poor outcomes increases in early or closely spaced pregnancies. J Nutr. 2003;133(5):1732S-1736S.

Koury MJ, Ponka P. New insights into erythropoiesis: the roles of folate, vitamin B12, and iron. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:105–31.

Lone FW, Qureshi RN, Emanuel F. Maternal anaemia and its impact on perinatal outcome. Tropical Med Int Health. 2004;9(4):486–90.

Räisänen S, Kancherla V, Gissler M, Kramer MR, Heinonen S. Adverse Perinatal Outcomes Associated with Moderate or Severe Maternal Anaemia Based on Parity in F inland during 2006–10. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28(5):372–80.

Haider BA, Olofin I, Wang M, Spiegelman D, Ezzati M, Fawzi WW. Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3443.

Chirande L, Charwe D, Mbwana H, Victor R, Kimboka S, Issaka AI, Baines SK, Dibley MJ, Agho KE. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in Tanzania: evidence from the 2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):165.

Akombi BJ, Agho KE, Hall JJ, Wali N, Renzaho A, Merom D. Stunting, wasting and underweight in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):863.

Pradhan A. Factors associated with nutritional status of the under five children. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010;1(1):6–8.

Adhikari D, Khatri RB, Paudel YR, Poudyal AK. Factors associated with Underweight among Under-Five children in eastern nepal: community-Based cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2017;5:350.

Channon AA. Can mothers judge the size of their newborn? Assessing the determinants of a mother’s perception of a baby’s size at birth. J Biosoc Sci. 2011;43(5):555–73.

Shakya K, Shrestha N, Bhatt M, Hepworth S, Onta S. Accuracy of low birth weight as perceived by mothers and factors influencing it: a facility based study in Nepal. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 2015;4(2):274–80.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to The DHS Program for allowing us to use the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data for further analysis.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (DMS, CC, EGH, and DL) contributed to the design of the study and the interpretation of data. DMS performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors (DMS, CC, EGH, and DL) read, critically revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the guidelines and regulations specified in the Declaration of Helsinki. The 2016 EDHS was approved by the National Research Ethics Review Committee of Ethiopia (NRERC) and ICF Macro International. Permission from The DHS Program was obtained to use the 2016 EDHS data for further analysis. This analysis was also approved by the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2018–0332).

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shifti, D.M., Chojenta, C., Holliday, E.G. et al. Maternal anemia and baby birth size mediate the association between short birth interval and under-five undernutrition in Ethiopia: a generalized structural equation modeling approach. BMC Pediatr 22, 108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03169-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03169-6