Abstract

Background

Black very low birth weight (VLBW; < 1500 g birth weight) and very preterm (VP, < 32 weeks gestational age, inclusive of extremely preterm, < 28 weeks gestational age) infants are significantly less likely than other VLBW and VP infants to receive mother’s own milk (MOM) through to discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The costs associated with adhering to pumping maternal breast milk are borne by mothers and contribute to this disparity. This randomized controlled trial tests the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to offset maternal costs associated with pumping.

Methods

This randomized control trial will enroll 284 mothers and their VP infants to test an intervention (NICU acquires MOM) developed to facilitate maternal adherence to breast pump use by offsetting maternal costs that serve as barriers to sustaining MOM feedings and the receipt of MOM at NICU discharge. Compared to current standard of care (mother provides MOM), the intervention bundle includes three components: a) free hospital-grade electric breast pump, b) pickup of MOM, and c) payment for opportunity costs. The primary outcome is infant receipt of MOM at the time of NICU discharge, and secondary outcomes include infant receipt of any MOM during the NICU hospitalization, duration of MOM feedings (days), and cumulative dose of MOM feedings (total mL/kg of MOM) received by the infant during the NICU hospitalization; maternal duration of MOM pumping (days) and volume of MOM pumped (mLs); and total cost of NICU care. Additionally, we will compare the cost of the NICU acquiring MOM versus NICU acquiring donor human milk if MOM is not available and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention (NICU acquires MOM) versus standard of care (mother provides MOM).

Discussion

This trial will determine the effectiveness of an economic intervention that transfers the costs of feeding VLBWand VP infants from mothers to the NICU to address the disparity in the receipt of MOM feedings at NICU discharge by Black infants. The cost-effectiveness analysis will provide data that inform the adoption and scalability of this intervention.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04540575, registered September 7, 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the United States, the burden of very low birth weight (VLBW; < 1500 g birth weight) birth is borne disproportionately by Black (non-Hispanic Black/African American) mothers, who are 2.2–2.6 times more likely than non-Black (non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, Asian) mothers to deliver VLBW infants [1]. This disparity affects Black families not only during the average 73-day hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [2] but continues after NICU discharge [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. VLBW infants are susceptible to potentially preventable morbidities during the NICU hospitalization that increase the risk of costly lifelong health and neurodevelopmental problems [11,12,13,14]. Mother’s own milk (MOM; excludes donor human milk (DHM)) feedings received in the NICU reduce the risks and associated costs of several neonatal morbidities and neurodevelopmental problems in VLBW infants [9, 15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, Black VLBW infants are significantly less likely to receive MOM feedings from birth until NICU discharge than non-Black infants, which precludes exclusive MOM feedings for the first 6 months of life recommended by authorities [21, 22], further amplifying disparity of prematurity in the Black population.

Although Black mothers of VLBW infants initiate lactation at rates comparable to non-Black mothers and have similar goals to sustain MOM provision through to NICU discharge [23, 24], Black VLBW infants are significantly less likely to receive MOM at NICU discharge [2, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Maternal adherence to a pumping regimen is required to sustain MOM provision, for which there are out-of-pocket and opportunity costs that are especially onerous for Black mothers, who are more likely to live in poverty [40]. In previous work, we found the difference between MOM receipt rates at NICU discharge for Black (23%) versus non-Black (43%) VLBW infants is mediated by poverty in Black mothers, despite these same mothers having comparable rates of MOM initiation and 87% indicating they wanted to provide MOM at NICU discharge [2, 23, 24, 39]. In contrast, when MOM is not available, the NICU provides pasteurized DHM and/or preterm formula, a current standard of care that subsidizes nutritionally inferior and significantly less protective milk feedings for this vulnerable population [41].

Barriers to breast pump use by mothers of VLBW infants: pump

In the United States, breast pumps provided by public nutrition and health programs typically do not meet minimum criteria of effectiveness, efficiency and comfort required for breast pump dependency and are intended instead to supplement MOM removal for breastfeeding mothers of term infants during brief separations such as return to employment [42, 43]. High-quality, hospital-grade electric breast pumps that permit simultaneous breast emptying are available, but the mother is often required to pay out-of-pocket for the rental costs. Ineffective, inefficient and uncomfortable breast pumps contribute to lack of adherence to consistent, frequent breast pump use, especially during the first 14 days postpartum, a critical period that includes achievement of secretory activation and coming to volume (≥500 mLs of MOM per day by postpartum day 14), both of which strongly predict receipt of MOM at NICU discharge [42, 44,45,46,47]. This time period coincides with the mother’s transition from hospital to home, often unwell herself and leaving behind a VLBW infant in the NICU. Added to this burden is that low-income mothers of VLBW infants may encounter a several-day delay before they can access an inferior pump for in-home use because they must either travel to a government social support agency office or wait for mail delivery [42, 44, 48, 49].

Barriers to breast pump use by mothers of VLBW infants: opportunity cost of providing breast milk

In addition to having access to an appropriate hospital-grade electric breast pump, mothers must adhere to a regimen of sustained breast pump use (6–8 times/day) for the entire NICU hospitalization. This regimen takes approximately 120 min daily [44]. This time represents opportunity costs borne by mothers, including forgoing paid and unpaid work to pump and store MOM and sanitize breast pump equipment.

Barriers to transporting pumped breast milk to the NICU

Additional out-of-pocket and opportunity costs are incurred to transport MOM pumped in the home to the NICU, and Black mothers are less likely to have access to a car than non-Black mothers [2, 50]. Data also indicate that Black mothers and family members have significantly fewer visits to the NICU compared to non-Black mothers and family members, and the frequency of visits is positively associated with infant receipt of MOM at NICU discharge [51]. For low-income women, these costs represent a greater proportion of overall income, and they must balance the perceived value of adherence against priorities that may be more immediate such as food and childcare expenses.

To address the maternal costs that serve as barriers to sustaining MOM feedings, we designed the Reducing Disparity in Receipt of Mother’s Own Milk in Very Low Birth Weight Infants (ReDiMOM) single-center randomized controlled trial, which tests an economic bundle (NICU acquires MOM) developed to offset these maternal costs. The NICU acquires MOM 3-part intervention bundle includes: 1) free hospital-grade electric pump for in-home use; 2) pickup of MOM by a hospital employee trained in safe handling and transport of MOM; and 3) payment for opportunity costs of time spent pumping. This intervention is compared to current standard of care, Mother provides MOM, in which the mother assumes these costs.

This innovative economic intervention bundle is based on principles of conditional cash transfers (CCTs). While CCTs have and are currently being investigated in term populations to increase lactation rates [52, 53], they have not been tested as an intervention to increase MOM provision by mothers of hospitalized very preterm (VP, < 32 weeks gestational age (GA), inclusive of extremely preterm (EP), < 28 weeks GA) infants. Data from an RCT in term infants demonstrate that the use of a CCT resulted in higher rates of any but not of exclusive breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks post-birth but had no effect on mothers’ decisions to initiate lactation [52]. Qualitative findings suggest that mothers perceive CCTs to have value for breastfeeding, compensating for ongoing breastfeeding challenges and facilitating achievement of targeted breastfeeding milestones [54]. Related research on the use of CCTs for breastfeeding in healthy but primarily disadvantaged populations reveals that 1) mothers value cash or cash equivalents more than other financial incentives such as grocery vouchers or baby supplies [54, 55] and 2) healthcare providers are generally positive but cautious about choosing the proper incentive and monitoring that its use does not impact other family or provider relationships [56,57,58,59,60].

The objectives of the ReDiMOM trial are to 1) compare infant and maternal MOM outcomes for the NICU acquires MOM intervention group versus mother provides MOM control group; 2) compare the cost of the NICU acquiring MOM versus the NICU acquiring DHM as supplemental feedings when MOM volume is insufficient; and 3) compare the cost-effectiveness of NICU acquires MOM versus mother provides MOM for maternal and infant outcomes.

Methods/design

Setting

This stratified, randomized controlled trial takes place in the NICU at Rush University Medical Center (RUMC), a level III Chicago perinatal center with over 2000 primarily high-risk births and over 100 VP, VLBW infants admitted to the NICU annually. The RUMC NICU has 72 private patient rooms and serves a racially and ethnically diverse group of families. Each infant’s room is equipped with a hospital-grade breast pump for use by the mother when visiting the NICU and a locked refrigerator for MOM storage, with excess MOM stored in large industrial freezers dedicated to MOM in the NICU. Lactation care is provided in the NICU through a unique model with nearly all direct lactation care provided by breastfeeding peer counselors (BPCs), who are mostly mothers of former RUMC NICU infants [61].

Eligibility criteria

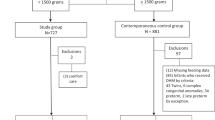

At study initiation (December 2020), maternal inclusion criteria were: 1) delivery of a VLBW infant at RUMC, 2) age ≥ 18 years, 3) willing and able to share a valid Social Security number, 4) fluent in English or Spanish, and 5) having plans to pump to provide MOM to her infant. Infant inclusion criteria were: 1) birth GA < 32 0/7 weeks, 2) birth weight < 1500 g, 3) no significant congenital anomalies or chromosomal defects, and 4) < 96 h of age at enrollment. After enrollment of the first 20 mothers, inclusion criteria were modified (August 2021) to remove the infant birth weight limitation. This was due to lower than anticipated enrollment and exclusion of VP infants with birth weight > 1500 g, which is well within the normal weight for an infant born at this gestation [62], and because lactation challenges in mothers of VP infants are primarily dependent on GA which corresponds to incomplete maturation or secretory differentiation of the mammary gland based on the duration of pregnancy. The eligibility criteria applied to mothers and infants, and modification was approved by the RUMC Institutional Review Board and the National Institutes of Health.

Exclusion criteria include: maternal health conditions that are incompatible with MOM provision per the clinical judgment of the NICU attending physician and one of the multi-PIs (ALP), mother has participated in ReDiMOM with a previous pregnancy, mother is enrolled in another study that impacts lactation, in the neonatologist’s opinion the infant is unlikely to survive, or mother is COVID-19 positive at time of delivery.

Informed consent

Mothers and their VP infants are included. Although pregnant women likely to deliver an infant with a GA < 32 0/7 weeks may be approached prenatally in order to discuss the study, written consent from the infant’s mother is obtained by study staff (grant project manager or research nurse) after the infant is born and eligibility criteria are confirmed. Enrollment must be completed by 96 h of age of the infant, a time window that accommodates mothers who may have perinatal complications and cannot be approached ethically prior to this time. The study protocol (18060410-IRB01) was initially approved by the RUMC Institutional Review Board (FWA00000482) on January 17, 2019.

Randomization procedure

Immediately after enrollment, mothers complete a brief questionnaire to collect GA and maternal race and ethnicity. Then, mothers are randomized to one of two groups (control – Mother provides MOM vs. intervention – NICU acquires MOM) in a 1:1 fashion using a stratified random assignment procedure contained in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) [63] and a randomization table created by the study biostatistician. Six strata have been created by crossing 1) two levels based on GA (extremely preterm < 28 weeks vs. very preterm 28–31 weeks) with 2) three racial and ethnic categories (Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic White/other). Within strata, condition is randomized within randomly ordered blocks of four and six participants, an approach that optimizes balance in sample sizes across conditions while also minimizing ability to deductively determine the condition of any upcoming participant. Randomization is performed by the study staff member using REDCap in the presence of the mother, ensuring that both mother and study staff member witness the assignment simultaneously. Because the unit of randomization is the mother, infants who are members of a set of multiples are allocated to the same group.

Control and intervention groups

All enrolled mothers do the following: 1) complete a W-9 form, including Social Security number for opportunity cost payment and study incentives; 2) maintain an electronic or paper pumping log for as long as they pump during the infant(s)’ NICU stay; 3) allow all of their pumped MOM to be weighed in the NICU; 4) complete study questionnaires via REDCap or with a member of the research team (Table 1); 5) provide a baseline MOM sample (2 mL) while pumping in the presence of a research team member or NICU nurse in the first few days post-delivery, which serves as a reference for later MOM samples to assure later MOM is from the same mother (see Milk Samples and Potential for Milk Adulteration); and 6) provide monthly milk samples of 5 mL while the infant is hospitalized.

All mothers receive standard lactation care including access to a free hospital-grade, double electric breast pump while hospitalized postpartum and access to a free hospital-grade, double electric breast pump for use at their infant(s)’ bedside in the NICU, as detailed in Table 2. In addition to standard lactation care, mothers assigned to the control group have the option to self-pay for the rental of a hospital-grade breast pump for home use at a subsidized rate. Mothers assigned to the intervention group receive the same standard lactation care as mothers in the control group with the following additions: 1) a hospital-grade electric smart breast pump (Medela Symphony PLUS® Breast Pump, Medela LLC, McHenry, IL) for home use at no charge to the mother while the infant is in the NICU and the mother continues to pump; 2) free pickup of pumped MOM from the mother’s home 2–3 times/week as needed; and 3) payment for pumping and handling her milk at the January 2020 Illinois minimum wage of $9.25/h for 120 min per day for each day that the mother pumps during her infant’s NICU hospitalization.

NICU acquires MOM intervention logistics

All study mothers receive a tablet to complete study questionnaires during the study, after which they are given the tablet for personal use. SMART breast pumps with data loggers that self-measure and store pumping start and stop times are used for all subjects in the intervention group, both in-hospital and at home. These stored data enable accurate and objective calculation of the number of pumping sessions and total minutes spent pumping. SMART pump data are automatically uploaded from the pump to the tablet, then transmitted via cellular data service to the secure study database using Bluetooth technology. In the case that the Bluetooth data transfer process malfunctions for an individual pumping(s) session, a back-up manual transfer protocol using a USB flash drive in the SMART pump to access stored data is used.

MOM pickup is performed by a milk courier, a security-cleared research team member who has been trained in safe handling and transport of MOM. As needed, the milk courier collects individual mothers’ MOM up to 3 times weekly and delivers it to the RUMC NICU. During the COVID-19 pandemic, MOM pickup is contactless. In brief, mothers place the MOM bottles in the same state (fresh/refrigerated or frozen) in study-provided plastic bags. An electric portable freezer and a larger cooler with ice packs are in the pick-up vehicle to maintain milk in refrigerated or frozen status. MOM temperature is monitored using the digital display on the electric freezer and a thermocouple thermometer and probe in the cooler (Fluke; Everett, WA). The milk courier records the temperature in a paper log at the beginning of the shift and at every stop. Additionally, the number of bottles and MOM state (fresh/refrigerated or frozen) are recorded in the log at pick-up and delivery to the NICU.

Payment is made on a weekly basis using rechargeable debit cards based on the number of days pumping was recorded by the in-hospital or home SMART pumps. The rechargeable debit cards are HIPAA compliant and developed specifically for clinical trials and research studies, requiring no protected health information to be shared with the vendor (CT Payer, Tampa, Florida).

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the infant’s receipt of MOM at NICU discharge, determined from the medical record for the last full day of hospitalization and categorized as “Yes” if the infant received exclusive or any MOM, and “No” if the infant received only formula. Receipt of MOM may be via direct breastfeeding or bottle, per the mother’s preference and availability. RUMC NICU standard lactation care includes education and support for direct breastfeeding for all mothers of hospitalized infants. VP infants in the RUMC NICU transition from DHM to formula at 33–34 weeks corrected GA, so infants only receive MOM or formula at the time of NICU discharge.

Secondary outcomes include the following: infant receipt of any MOM (any or none) during the NICU hospitalization, duration of any MOM feedings (days with any MOM feeding), and cumulative dose (total mL/kg) of MOM feedings received by the infant during the NICU hospitalization; maternal duration of MOM pumping (days) and volume of MOM pumped (mLs); and total cost of care, all determined at the time of infant discharge from the NICU. Duration of MOM pumping is calculated as the number of days the mother pumped any MOM. Total cost of care includes program, healthcare system and participant (maternal and infant) costs. Program costs include the cost of the intervention (rental costs for pumps used at home, milk courier time and mileage, supplies required for MOM pick up, opportunity cost payment to mothers). Healthcare system costs include costs borne by healthcare providers or third-party payers, such as the cost of the hospital stay, DHM and formula (Table 3). Participant costs include the opportunity cost of pumping and delivering MOM to the NICU (in the control group) and other participant and caregiver informal health sector and non-health sector out-of-pocket costs, such as travel costs to and from the NICU and the cost of care for other children during visits to the NICU.

Study visits and timeline

At enrollment, all mothers are given a study tablet with cellular service provided by the study and a CT Payer Visa debit card, loaded with an enrollment incentive of $20. Cellular service is discontinued at NICU discharge, and mothers keep the tablet at the end of the study. Intervention group mothers are also given a SMART pump at enrollment. All study questionnaires and data collection procedures can be completed remotely with the study tablet. Mothers randomized to the intervention group return the SMART pump when the infant is discharged from the NICU or when the mother discontinues pumping, whichever occurs sooner.

Sample size

For the primary outcome, we estimated power based on expected rates of infants receiving MOM at NICU discharge of 33% in the control group vs 51% in the intervention group (OR = 2.1) using estimates from published U.S. studies that report MOM at discharge for VLBW infants [25, 34, 36, 64]. The published rates are generally higher than our assumptions, but these rates reflect much lower rates of socio-economic disadvantage than found in our population, because they represent statewide data [34, 64] and/or occur in higher socio-economic settings [25, 64]. Under these assumptions, using SAS Proc Power we calculated a required sample size of 256 mothers (128 per group) to have 80% power to detect an effect of OR = 2.1 or greater. To account for 10% attrition, we will enroll 284 mothers and their infants. All power analyses were conducted with α = .05, and 2-tailed tests.

Data collection plan

Data are collected from several sources: 1) subject contact information form, 2) REDCap surveys, 3) data extraction from the electronic medical record and hospital financial system, 4) SMART breast pump and 5) measurement of pumped MOM volume. Data extracted from the electronic medical record include maternal and infant demographic characteristics and medical diagnoses, daily feeding volume (mL) and type (MOM, DHM, formula including name), daily receipt of mechanical ventilation, daily receipt of parenteral nutrition, and dates of hospitalization for infants. Coded numbers are used in association with data and samples to maintain confidentiality, and all records are maintained on a secure RUMC network drive that can only be accessed by study personnel using password protected login information.

Pumping duration is collected through mothers’ records of each pumping session duration in the REDCap Pumping Log or paper pumping logs that are transferred into REDCap by study staff. Volume of pumped MOM is collected by measuring exact weights (nearest 0.1 g) of empty and filled MOM storage containers using scientific scales (Tanita, Japan), then calculating MOM volume by subtracting the empty weight from the filled weight (1 g = 1 mL) [46, 65]. Filled containers are weighed by research staff, BPCs and/or bedside nurses when brought to the NICU, and weight and container size are recorded for later entry into study database.

Table 3 summarizes the program, healthcare system and participant (maternal and infant) resources and costs that will be collected. Detailed, micro-level cost data for the NICU hospital stay are retrieved from the RUMC financial system, which includes both hospital and physician resources used and their associated costs [15, 17]. Program resources and costs are collected via NICU financial records, study records, and direct observation of a subset of encounters to measure the duration of time for some activities (time and motion studies). All costs will be adjusted to 2020 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Items, All Urban Consumers, from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics [66].

Milk samples and potential for milk adulteration

An unlikely theoretical risk is the possibility that an intervention group mother would adulterate and/or replace her pumped MOM for infant feeding with a substitute, including milk from another lactating woman, to continue receiving payment for the opportunity costs of pumping. To address this concern, MOM from both groups is tested for adulteration at serial time points during the infant’s NICU hospitalization and mothers are informed about testing at the time of enrollment. The first 2 mL MOM sample is pumped in the presence of a research team member or NICU nurse during the mother’s maternity hospitalization or in the first few days post-delivery and serves as the reference sample, documenting maternal-specific DNA. Subsequent 2-5 mL MOM samples brought to the NICU are collected and tested randomly on a monthly basis. MOM samples remain frozen at -80C and will be shipped to The Ohio State University for testing by study co-investigator (JJK) in Year 5. Samples will be tested for the most common potential diluents for which analyses are available: infant formula (cow’s milk based), cow’s milk, goat’s milk, soy milk, almond milk, rice milk, and breast milk from another woman.

Statistical methods

All analyses will use an intent-to-treat approach in which participants will be analyzed according to the group to which they were assigned. All analyses will include terms for GA (< 28 weeks vs. 28–32 weeks), sex and racial and ethnic category (Black, Hispanic, White/other).

To test the effect of the intervention on infant receipt of any MOM at NICU discharge, a logistic regression model with treatment group and covariates previously described will be constructed. Similar regression models will be used to test secondary outcomes, with the model function (e.g., normal, ordinal, Poisson, time to event) appropriate to the distribution of the outcome being considered. In addition to the main effects of the intervention, secondary analyses will be conducted to test whether intervention effects vary as a function of infant GA and racial and ethnic category.

To compare the cost of the NICU acquiring MOM versus the NICU acquiring DHM as supplemental feedings when MOM volume is insufficient, the NICU cost per mL of acquiring MOM versus acquiring DHM will be calculated by multiplying the number of units of each resource (MOM or DHM) by its respective per-unit cost. The costs of the NICU acquiring MOM include all standard lactation care costs and the cost of the intervention components. The costs of the NICU acquiring DHM include the hospital’s purchase price of DHM and costs associated with processing and storing the DHM. The per-unit cost of acquiring MOM will be compared with the per-unit cost of acquiring DHM using a generalized linear regression model with a log link function and gamma distribution, including covariates previously described.

The cost-effectiveness analysis will compare NICU acquires MOM versus mother provides MOM and will be conducted from the societal perspective. The primary effectiveness measure will be receipt of MOM at NICU discharge, and additional analyses will be performed for the secondary outcomes. Cost-effectiveness will be calculated as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for NICU acquires MOM relative to Mother provides MOM. Additional cost-effectiveness analyses will be conducted from the program, healthcare system and participant perspectives. The 95% confidence intervals using non-parametric estimation will be computed for the ICERs and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves derived from probabilistic sensitivity analysis will be plotted to summarize uncertainty. Cost-effectiveness analyses will follow best practices outlined by the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [67].

Data safety monitoring

An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board reviews adverse events and monitors data safety. Members of the Data Safety Monitoring Board include experts in the field of pediatrics, neonatology, biostatistics and clinical trials.

Discussion

By employing an innovative economic-based strategy utilizing CCTs to overcome barriers faced by Black mothers, this randomized controlled trial tests whether adherence to pumping improves, as measured by whether a greater proportion of infants in the NICU acquires MOM intervention group receive MOM at the time of NICU discharge compared to infants in the mother provides MOM control group. We anticipate that the societal cost of the NICU acquiring MOM will be equal to or less than the cost of an equivalent volume of DHM feedings supplemented with formula due to the reductions in morbidities associated with MOM but not DHM and formula feedings. Scalability of the NICU acquires MOM intervention is informed by the fact that it is aligned with national and global recommendations and demand for strategies to increase MOM feedings in the VP infant population [68,69,70]. Despite the known benefits, disparities in MOM provision based on race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status are prevalent in US NICUs. Conceptualizing MOM feedings as an integral part of NICU care requires consideration of who bears the costs of MOM provision and testing novel interventions to offset costs traditionally borne by mothers, which are more onerous to low-income women [37, 71].

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available between 2 and 5 years after publication of the final study results to investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and deemed scientifically appropriate per the ReDiMOM principal investigators.

Abbreviations

- ReDiMOM:

-

Reducing Disparity in Receipt of Mother’s Own Milk in Very Low Birth Weight Infants

- VLBW:

-

Very low birth weight (< 1500 g birth weight)

- VP:

-

Very preterm, < 32 weeks gestational age

- MOM:

-

Mother’s own milk

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- DHM:

-

Donor human milk

- CCTs:

-

Conditional cash transfers

- GA:

-

Gestational age

- EP:

-

Extremely preterm, < 28 weeks gestational age

- RUMC:

-

Rush University Medical Center

- BPC:

-

Breastfeeding peer counselor

- REDCap:

-

Research Electronic Data Capture

References

March of Dimes. Very low birthweight by race/ethnicity: United States, 2017–2019 average. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/Peristats/ViewSubtopic.aspx?reg=99&top=4&stop=54&lev=1&slev=1&obj=1. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

Riley BS, Schoeny M, Rogers L, Asiodu IV, Bigger HR, Meier PP, et al. Barriers to human milk feeding at discharge of VLBW infants: Evaluation of neighborhood structural factors. Breastfeed Med. 2016;117:335–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.0185.

Hack M. Young adult outcomes of very-low-birth-weight children. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11(2):127–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2005.11.007.

Stephens BE, Vohr BR. Neurodevelopmental outcome of the premature infant. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2009;56(3):631–46 0.1016/j.pcl.2009.03.005.

Reidy N, Morgan A, Thompson DK, Inder TE, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Impaired language abilities and white matter abnormalities in children born very preterm and/or very low birth weight. J Pediatr. 2013;162(4):719–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.017.

Thompson DK, Lee KJ, Egan GF, Warfield SK, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ, et al. Regional white matter microstructure in very preterm infants: predictors and 7 year outcomes. Cortex. 2014;52:60–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2013.11.010.

Kuzniewicz MW, Wi S, Qian Y, Walsh EM, Armstrong MA, Croen LA. Prevalence and neonatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorders in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2014;164(1):20–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.021.

Treyvaud K, Ure A, Doyle LW, Lee KJ, Rogers CE, Kidokoro H, et al. Psychiatric outcomes at age seven for very preterm children: rates and predictors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):772–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12040.

Patra K, Hamilton M, Johnson TJ, Greene M, Dabrowski E, Meier PP, et al. NICU human milk dose and 20-month neurodevelopmental outcome in very low birth weight infants. Neonatology. 2017;112(4):330–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475834.

Patra K, Greene MM. Health care utilization after NICU discharge and neurodevelopmental outcome in the first 2 years of life in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(5):441–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1608678.

Kapellou O, Counsell SJ, Kennea N, Dyet L, Saeed N, Stark J, et al. Abnormal cortical development after premature birth shown by altered allometric scaling of brain growth. PLoS Med. 2006;3(8):e265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.003026.

Manzoni P, Arisio R, Mostert M, Leonessa M, Farina D, Latino MA, et al. Prophylactic fluconazole is effective in preventing fungal colonization and fungal systemic infections in preterm neonates: a single-center, 6-year, retrospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e22–32. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2227.

Jarjour IT. Neurodevelopmental outcome after extreme prematurity: a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(2):143–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.027.

Schmidt B, Asztalos EV, Roberts RS, Robertson CM, Sauve RS, Whitfield MF, et al. Impact of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, brain injury, and severe retinopathy on the outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants at 18 months: results from the trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1124–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.9.1124.

Patel AL, Johnson TJ, Robin B, Bigger HR, Buchanan A, Christian E, et al. Influence of own mother's milk on bronchopulmonary dysplasia and costs. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102(3):F256–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-310898.

Johnson TJ, Patel AL, Bigger HR, Engstrom JL, Meier PP. Cost savings of human milk as a strategy to reduce the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Neonatology. 2015;107(4):271–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000370058.

Johnson TJ, Patel AL, Jegier BJ, Engstrom JL, Meier PP. Cost of morbidities in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):243–9.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.013.

Patel AL, Johnson TJ, Engstrom JL, Fogg LF, Jegier BJ, Bigger HRM, et al. Impact of early human milk on sepsis and health care costs in very low birthweight infants. J Perinatol. 2013;33(7):514–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2013.2.

Blesa M, Sullivan G, Anblagan D, Telford EJ, Quigley AJ, Sparrow SA, et al. Early breast milk exposure modifies brain connectivity in preterm infants. Neuroimage. 2018;184:431–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.045.

Lechner BE, Vohr BR. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed human milk: a systematic review. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(1):69–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2016.11.004.

2020 Topics & Objectives: Maternal, Infant, and Child Health. 2018; Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed 8 Oct 2021.

ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition, Agostoni C, Braegger C, Decsi T, Kolacek S, Koletzko B, et al. Breast-feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jul;49(1):112–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819f1e05.

Hoban R, Bigger H, Patel AL, Rossman B, Fogg LF, Meier P. Goals for human milk feeding in mothers of very low birth weight infants: how do goals change and are they achieved during the NICU hospitalization? Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(6):305–11. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.0047.

Fleurant E, Schoeny M, Hoban R, Asiodu IV, Riley B, Meier PP, et al. Barriers to human milk feeding at discharge of very-low-birth-weight infants: maternal goal setting as a key social factor. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:20–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2016.0105.

Bixby C, Baker-Fox C, Deming C, Dhar V, Steele C. A multidisciplinary quality improvement approach increases breastmilk availability at discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit for the very-low-birth-weight infant. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:75–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.0141.

Dereddy NR, Talati AJ, Smith A, Kudumula R, Dhanireddy R. A multipronged approach is associated with improved breast milk feeding rates in very low birth weight infants of an inner-city hospital. J Hum Lact. 2015;31(1):43–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334414554619.

Parker MG, Burnham L, Mao W, Philipp BL, Merewood A. Implementation of a donor milk program is associated with greater consumption of mothers' own milk among VLBW infants in a US, level 3 NICU. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(2):221–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415598305.

Philipp BL, Brown E, Merewood A. Pumps for peanuts: leveling the field in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2000;20(4):249–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7200365.

Sisk PM, Lovelady CA, Dillard RG, Gruber KJ. Lactation counseling for mothers of very low birth weight infants: effect on maternal anxiety and infant intake of human milk. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e67–75. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0267.

Engstrom JL, Patel AL, Meier PP. Eliminating disparities in mother's milk feeding in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2017;182:8–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.038.

Pineda RG. Predictors of breastfeeding and breastmilk feeding among very low birth weight infants. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(1):15–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2010.0010.

Meier PP, Patel AL, Bigger HR, Rossman B, Engstrom JL. Supporting breastfeeding in the neonatal intensive care unit: rush Mother's Milk Club as a case study of evidence-based care. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2013;60(1):209–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2012.10.007.

Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, McKinley LT, Wright LL, Langer JC, et al. Beneficial effects of breast milk in the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e115–23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2382.

Lee HC, Gould JB. Factors influencing breast milk versus formula feeding at discharge for very low birth weight infants in California. J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):657–62.e1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.064.

Sisk PM, Lovelady CA, Dillard RG, Gruber KJ, O'Shea TM. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with human milk feeding in very low birth weight infants. J Hum Lact. 2009;25(4):412–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334409340776.

Brownell EA, Lussier MM, Hagadorn JI, McGrath JM, Marinelli KA, Herson VC. Independent predictors of human milk receipt at neonatal intensive care unit discharge. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(10):891–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1363500.

Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, Goldstein BA, Draper D, Phibbs CS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3): https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0918.

Parker MG, Burnham LA, Melvin P, Singh R, Lopera AM, Belfort MB, et al. Addressing disparities in mother's milk for VLBW infants through statewide quality improvement. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183809. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3809.

Patel AL, Schoeny ME, Hoban R, Johnson TJ, Bigger H, Engstrom JL, et al. Mediators of racial and ethnic disparity in mother's own milk feeding in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res. 2019;85:662–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0290-2.

Semega JL, Fontenot KR, Kollar MA. Income and poverty in the United States: 2016 Current Population Reports. United States Census Bureau; US Department of Commerce- Economics and Statistics Administration. 2017;P60–259:1–72.

Meier P, Patel A, Esquerra-Zwiers A. Donor human milk update: evidence, mechanisms, and priorities for research and practice. J Pediatr. 2017;180:15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.027.

Meier PP, Patel AL, Hoban R, Engstrom JL. Which breast pump for which mother: an evidence-based approach to individualizing breast pump technology. J Perinatol. 2016;36(7):493–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.14.

Hawkins SS, Dow-Fleisner S, Noble A. Breastfeeding and the affordable care act. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2015;62(5):1071–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2015.05.002.

Meier PP, Johnson TJ, Patel AL, Rossman B. Evidence-based methods that promote human milk feeding of preterm infants: an expert review. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2016.11.005.

Hoban R, Bigger H, Schoeny M, Engstrom J, Meier P, Patel AL. Milk volume at 2 weeks predicts mother's own milk feeding at neonatal intensive care unit discharge for very low birthweight infants. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(2):135–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2017.0159.

Hoban R, Patel AL, Medina Poeliniz C, Lai CT, Janes J, Geddes D, et al. Human milk biomarkers of secretory activation in breast pump-dependent mothers of premature infants. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(5):352–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2017.0183.

Medina Poeliniz C, Engstrom JL, Hoban R, Patel AL, Meier P. Measures of secretory activation for research and practice: an integrative review. Breastfeed Med. 2020;15(4):191–212. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2019.0247.

Parker LA, Sullivan S, Krueger C, Kelechi T, Mueller M. Effect of early breast milk expression on milk volume and timing of lactogenesis stage II among mothers of very low birth weight infants: a pilot study. J Perinatol. 2012;32(3):205–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2011.78.

Parker LA, Sullivan S, Krueger C, Mueller M. Association of timing of initiation of breastmilk expression on milk volume and timing of lactogenesis stage II among mothers of very low-birth-weight infants. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(2):84–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0089.

Duque V, Pilkauskas NV, Garfinkel I. Assets among low-income families in the great recession. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192370.

Greene MM, Rossman B, Patra K, Kratovil A, Khan S, Meier PP. Maternal psychological distress and visitation to the neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(7):e306–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12975.

Relton C, Strong M, Thomas KJ, Whelan B, Walters SJ, Burrows J, et al. Effect of financial incentives on breastfeeding: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):e174523. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4523.

Washio Y, Collins BN, Hunt-Johnson A, Zhang Z, Herrine G, Hoffman M, et al. Individual breastfeeding support with contingent incentives for low-income mothers in the USA: the 'BOOST (Breastfeeding Onset & Onward with support tools)' randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e034510-2019-034510. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034510.

Johnson M, Whelan B, Relton C, Thomas K, Strong M, Scott E, et al. Valuing breastfeeding: a qualitative study of women's experiences of a financial incentive scheme for breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1651-7.

Becker F, Anokye N, de Bekker-Grob E, Higgins A, Relton C, Strong M, et al. Women's preferences for alternative financial incentive schemes for breastfeeding: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2018;12(4):e0194231. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194231.

Whelan B, Thomas KJ, Van Cleemput P, Whitford H, Strong M, Renfrew MJ, et al. Healthcare providers' views on the acceptability of financial incentives for breastfeeding: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:355–2393–14-355. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-355.

Whitford H, Whelan B, van Cleemput P, Thomas K, Renfrew M, Strong M, et al. Encouraging breastfeeding: financial incentives. Pract Midwife. 2015;18(2):18–21.

Moran VH, Morgan H, Rothnie K, MacLennan G, Stewart F, Thomson G, et al. Incentives to promote breastfeeding: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e687–702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2221.

Morgan H, Hoddinott P, Thomson G, Crossland N, Farrar S, Yi D, et al. Benefits of incentives for breastfeeding and smoking cessation in pregnancy (BIBS): a mixed-methods study to inform trial design. Health Technol Assess. 2015 Apr;19(30):1–522 vii-viii.

Thomson G, Morgan H, Crossland N, Bauld L, Dykes F, Hoddinott P, et al. Unintended consequences of incentive provision for behaviour change and maintenance around childbirth. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111322.

Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Rossman B. Breastfeeding peer counselors as direct lactation care providers in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Hum Lact. 29(3):313–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334413482184.

Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):e214–24. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0913.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

Parker MG, Gupta M, Melvin P, Burnham LA, Lopera AM, Moses JM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mother's milk feeding for very low birth weight infants in Massachusetts. J Pediatr. 2019;204:134–141.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.036.

Hoban R, Medina Poeliniz C, Somerset E, Tat Lai C, Janes J, Patel AL, et al. Mother's own milk biomarkers predict coming to volume in pump-dependent mothers of preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2021; 228:P44–52.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.09.010.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index (CPI) Databases. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm. Accessed October 5, 2021.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA;316(10):1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12195.

World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding Fact Sheet. 2018; Available at: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding. Accessed 8 Oct 2021.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–41. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3552.

Parker MG, Patel AL. Using quality improvement to increase human milk use for preterm infants. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(3):175–86. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.03.007.

Parker MG, Greenberg LT, Edwards EM, Ehret D, Belfort MB, Horbar JD. National trends in the provision of human milk at hospital discharge among very low-birth weight infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(10):961–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2645.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD013969. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ALP and TJJ are multiple principal investigators for the ReDiMOM trial and led the development of the protocol, drafting and revising the manuscript. PPM and MES are co-investigators and contributed substantially to the development of the protocol and revising the manuscript. AB and JJ are study team members and contributed to the protocol and revising the manuscript. JJK is a co-investigator and JZ and SAK are study consultants, and they contributed to the development of the protocol and revising the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Consent to participate was obtained from the mothers on behalf of themselves and the minors included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

TJJ has provided consultation to Medela, Inc., for the development of a calculator for cost savings of MOM feedings. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, T.J., Meier, P.P., Schoeny, M.E. et al. Study protocol for reducing disparity in receipt of mother’s own milk in very low birth weight infants (ReDiMOM): a randomized trial to improve adherence to sustained maternal breast pump use. BMC Pediatr 22, 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-03088-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-03088-y