Abstract

Background

It is not yet known how antibiotics may affect Serious Bacterial Infections (SBI). Our aim is to describe the presentation, management, and serious bacterial infections (SBI) of febrile children on or off antibiotics.

Methods

Retrospective, cohort study of febrile Emergency Department patients, 0–36 months of age, at a single institution, between 2009and 2012.

Results

Seven hundred fifty-three patients were included: 584 in the No-Antibiotics group and 169 (22%) in the Antibiotics group. Age and abnormal lung sounds were predictors for being on antibiotics (OR 2.00 [95% CI 1.23–3.25] and OR 1.04 [95% CI 1.02–1.06] respectively) while female gender, and lower temperatures were negative predictors (OR 0.68 [95%0.47–0.98] and OR 0.47 [95% CI 0.32–0.67] respectively). Antibiotics were prescribed by a physician 89% of the time; the most common one being Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid (39%). The antibiotic group got more blood tests (57% vs 45%) and Chest X-Rays (37% vs 25%). Overall, the percent of SBIs (and pneumonias) was statistically the same in both groups (6.5% in the No-antibiotic group VS 3.6%).

Conclusions

Children presenting on antibiotics and off antibiotics were significantly different in their presentation and management, although the overall percentages of SBI were similar in each group. Further investigations into this subgroup of febrile children are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Children with fever constitute a substantial proportion of ambulatory emergency department (ED) visits [1]. Serious bacterial infection (SBI) rates are still elevated: up to 12.8% in febrile infants less than 60 days of age [2], and up to 7.2% in children less than 5 years of age [3]. In the 1990s, several studies developed prediction rules to identify SBI in febrile infants [4,5,6,7]. Many have been revisited as the bacterial landscape has changed especially with the advent of vaccines [8,9,10,11]. However, as antibiotic use may alter the patients’ microbiome [12] and test results [13], including cultures [14], febrile children on antibiotics are typically excluded from studies on SBI [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. In fact, there is no data describing febrile children presenting to the ED on antibiotics, nor the type of SBIs they may present with. Therefore, it is unclear how to use the data on SBI predictors and diagnosis in this subpopulation of febrile children already.

The objective of this study was to describe previously healthy children, presenting to the ED with fever, stratified by previous antibiotic use or not; and to describe the distribution and types of SBI in those two groups.

Methods

Study design

We carried out a retrospective, cohort study of patients 0–36 months of age presenting with fever to the ED of the American University of Beirut Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon, between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2012. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. This is an ED of a tertiary care center, in a middle-income country where pediatric patients during the time of our data collection where seen primarily by pediatricians with or without intensive care training.

Population

We included all patients 0 to 36 months of age, with fever (rectal temperature ≥ 38 °C or ≥ 37.6 °C by any other route) measured in the ED, at home or at the pediatrician’s office. We retrieved the records of patients with one or more of the following chief complaints, ED discharge diagnoses or hospital admission/discharge diagnoses: fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, fussy, lethargy, decreased activity, seizure activity, vomiting, diarrhea, pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI), viral illness, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, cellulitis, abscess, meningitis, encephalitis, sepsis, septic shock, bacteremia.

We excluded all patients with an underlying immunosuppressive disease or immunosuppressive medication; with an underlying chronic disease (that may impact fever management); with a previous UTI; and admitted to the ED or hospital within the last 2 weeks.

Data collection

We included information on: patient demographics, clinical presentation, and management. Data was collected by 4 physicians who had a training by the principle investigator in order to use the same terminology and categorize signs and symptoms in the same way.

Definitions

We defined Serious Bacterial Infection (SBI) as one of the following:

- 1-

Urinary Tract Infection: a positive urine culture > 5000 cfu/ml for suprapubic aspiration (SPA), > 10,000 cfu/ml for a sterile catheterization in children < 2 months old; > 50,000 cfu/ml AND pyuria by urinalysis (WBC > 5/mm3) by sterile catheterization or SPA and > 100,000 cfu/ml for clean catches [2, 15].

- 2-

Bacteremia: a positive bacterial culture with a true pathogen other than Coagulase Negative Staphylococcus or other commensal bacteria (such as Staphylococcus epididymis and Diphteroid), which were considered contaminants unless treated as true infections per documentation [2, 7, 16, 17].

- 3-

Meningitis: a positive cerebrospinal fluid culture other than coagulase negative Staphylococcus which was considered a contaminant, unless treated as true infections per documentation [2, 18].

We defined Pneumonia as a Chest X-Ray reported by a radiologist as definite or probable for a pneumonia (“Infiltrate”, “consolidation” or “concerning for developing pneumonia”) irrespective of microbiological results as these are low yield [19]. This definition reflects clinical practice.

We defined tachypnea and tachycardia as values above the upper limit of normal for age, as per Additional file 1. We defined hypoxia as an oxygen saturation ≤ 97%.

We defined abnormal perfusion as any documentation of mottled skin, or capillary refill greater than 3 s, or a flash capillary refill consistent with possible warm shock.

The “Antibiotic” group included all children who were on antibiotics prior to the ED visit as per care giver’s report or who had received antibiotics within the past 2 weeks. The “No-Antibiotic” group included the children who had not received any antibiotics prior to the ED visit.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24.0 was used for data cleaning, management and analyses. Descriptive statistics were summarized by presenting the number and percentage for categorical variables, whereas continuous ones were presented by mean and standard deviation (±SD). In the bivariate analysis, the association between antibiotic use and other categorical variables was assessed using Chi-Square test, whereas Student’s t-test was used for the association with continuous variables. Multivariate regression analysis was used to adjust for potentially confounding variables. Variables which were statistically significant in the analysis or clinically important were included in the multivariate analysis. The stepwise logistic regression analysis assessed the association between antibiotic use and the different predictors. P-value of 0.05 was set for the entry of potential predictors into the model, whereas a p-value of 0.1 was set for removal from the model. The results were presented by the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing data was left empty.

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

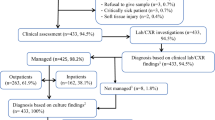

We retrieved 1427 patients from the medical records; 753 met our inclusion criteria and were analyzed: 584 in the No-Antibiotics group and 169 (22.4%) in the Antibiotics group (Fig. 1).

As per Table 1, children in the Antibiotic group were significantly older (21.2 months ±9.2 compared to 16.9 ± 10.3; p < 0.0001), in fact none of the children < 90 days of age had received antibiotics prior to presentation in this sample. In addition, the Antibiotic group was mostly of male gender (62.7% compared to 51.4%, p < 0.009), and had a longer duration of fever prior to presentation (4.5 days ±5.5 compared to 2.1 ± 1.6, p < 0.0001). Interestingly, associated symptoms presented as frequently in both groups except for a sore throat: 10.1% in the Antibiotic group compared to 4.8% in the No-Antibiotic group (p = 0.01) (Table 1).

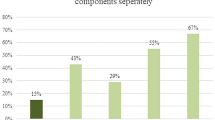

The specifics of the antibiotic use within 2 weeks prior to presentation to the ED with a fever were quite varied in the Antibiotic group. The majority, (82%) were still takings antibiotics at presentation; and 10.8% were taking multiple. The mean days of antibiotic use was 3.5 ± 3.0 days. The antibiotic was prescribed by a Medical Doctor in 89.3% (101/113) of the cases. Finally, the most common antibiotic used was an oral 3rd generation cephalosporin at 33.2% followed by a combination of penicillin/beta-lactamase inhibitor at 31.9%.. Interestingly, up to 10.2% had received intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) 3rd generation cephalosporin,, prior to the ED visit.

When comparing the two sub-groups (Table 1), we noted that the Antibiotic group was more likely to be tachycardic (84% compared to 53.2%; p < 0.0001); to have abnormal lung sounds (20.1% compared to 10.4%; p = 0.001), an abnormal tympanic membrane (27.1% compared to 18.8%; p = 0.02); and abnormal tonsils (59.1% compared to 48.5%; p = 0.02). While the No-Antibiotic group were more likely to have an abnormal mental status (12.2% compared to 6%; p = 0.02) and to be looking more sickly (4.8% compared to 0; p < 0.001).

The Antibiotic group was more frequently tested by blood work (56.8% compared to 45.0%, p = 0.01) and chest radiography (37.3% compared to 24.7%, p = 0.001) (see Table 2). But when tested, the No-Antibiotic group had more bandemia than the Antibiotic group (mean 0.9 ± 5.0 compared to 0.1 ± 0.6, p = 0.02); a more frequently positive urine analysis (positive leukocyte esterase in 31.8% compared to 9.4%, p = 0.01 and positive for WBCs in 23.8% compared to 6.3%, p = 0.03) and to have influenza (p = 0.03). Interestingly, the frequency of fluid boluses and admissions was the same in both groups.

In the multivariate analysis reported in Table 3, age, and abnormal lung sounds were predictors for being on antibiotics. In fact, each 1 month increase in age increased the odds of being on antibiotics by 1.04 (95% CI: 1.02–1.06). Finally, of all the patients, 5.8% had at least one SBI. When analyzed by Antibiotic vs. No-Antibiotic group, the number of SBIs remained similar with no statistical difference (p = 0.15). However, UTIs were statistically more common in the No-Antibiotic group (12.5 and 21.9%; p = 0.002 and 6.2 and 2.4%; p = 0.05, respectively) (Table 4). Our data on bacteremia and meningitis were too few to analyze further. Since there were no children < 90 days old on antibiotics, we did not do any subgroup analysis for this age in this comparative study.

Discussion

Children presenting with antibiotics to the ED are usually excluded from studies on febrile children. Our study is the first to describe febrile children on antibiotics. In our sample, a third of the febrile, healthy children presenting to the ED were already on antibiotics. These were significantly different than the group off antibiotics and were managed slightly differently. Interestingly, the overall percentages of SBIs were similar in each group, so were the admission and IV fluid bolus rates.

We found that older age, female gender, fever and abnormal lung sounds in the ED, were predictors of being on antibiotics prior to the visit. In addition, we showed that the antibiotic group had more focal infections (lungs, tonsils, and ears) and was perhaps started on antibiotics for that reason; this may be explained by the fact that upper respiratory infections (URTI) are the most common reason for being on outpatient antibiotics [20]. The No-Antibiotic group however did not have apparent focal infections but when they presented to the ED, they were sicker. Yet our overall rate of at least one SBI (Bacteremia, Meningitis and UTI) was 5.8% without reaching any significant difference when comparing both sub-groups on and off-antibiotics. This may be an underestimation in the Antibiotic group if these affected cultures; however, this also reflects the daily practice we face in the ED. Given the similar rates of SBI in both groups, and one study noting that antibiotics may in fact prevent complications in certain infections such as URTI, pharyngitis, otitis and hence have a protective effect [21], further studies looking at the clinical impact of this antibiotic use are needed.

The most common source of antibiotic prescription in our country remains the physician but only at 89.3%. It is worth noting that our Lebanese pharmacies can still issue an antibiotic without a prescription. This fits with results from a recent Lebanese and Middle Eastern report that antibiotics were one of the most common medications self-prescribed by patients [22, 23].

Finally, in our sample, the most common antibiotics used were broad spectrum antibiotics, such as a 3rd generation cephalosporin. As we noted that most patients on antibiotics had abnormal lung sounds, tympanic membranes or tonsils, perhaps these were to treat a pneumonia, otitis or Streptococcus tonsillitis. This is an interesting choice given the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines to treat these primarily with Amoxicillin [24,25,26]. However, the use of a combined penicillin/beta-lactam inhibitor does follow local patterns of streptococcus pneumonia resistance to Amoxicillin [27, 28] but is not justified for Streptococcus tonsillitis. In addition, it is important to note that 10% had a parenteral form prescribed. Lack of adherence to antibiotic use guidelines has already been documented in Lebanon [28, 29] The above information on antibiotic use and misuse begs for national campaigns for antibiotic stewardship including guidelines and education A 2016 study of Lebanese hospitals showed that only 7% knew what the term antimicrobial stewardship meant, although around 65% reported having some type of antibiotic control program in the hospital and only 50% had an outcome measure in place [30]. However, in recent years, The Lebanese Society of Infectious Diseases has published several articles guiding the treatment of specific diseases such as UTIs and complicated intraabdominal infections [31, 32]. .Moreover, the Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics (APUA) has a Lebanese chapter that has been active especially in antibiotic stewardship education [33], braving the first steps to promoting antibiotic stewardship programs in the country; steps that other nations with a similar pattern of antibiotic use should also follow.

Limitation

In this retrospective study our data is limited by the accuracy and completeness of the medical records, therefore no inferences were made on immunization and vital signs because of this. We don’t have the exact timing of the laboratory draws, but all reported laboratory results were done during the sentinel ED visit. We also do not have information on the duration of antibiotic pretreatment, nor why it was given and therefore cannot determine its exact impact on cultures and laboratory results. In addition, the SBI rates of the pretreated group may be underreported as the antibiotics could have influenced the culture results. However, this reflects the reality of our clinical practice and decisions we have to make.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first study of its kind to describe febrile children already on antibiotics presenting to the ED compared to those not on antibiotics. It generated interesting preliminary data that opens doors to further investigations on predictors for testing febrile patients on antibiotics, on understanding how to interpret the test results and more importantly to understand predictors of SBI and SBI outcomes in this group.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AAP:

-

American Academy of Pediatrics

- APUA:

-

Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics

- Cfu/ml:

-

Colony forming unit/milliliter

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- IM:

-

Intramuscular

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SBI:

-

Serious bacterial infection

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPA:

-

Suprapubic aspiration

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- URTI:

-

Upper respiratory tract infection

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

Rui P, Kang K. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2014 emergency department summary tables. 2014. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2014_ed_web_tables.pdf.

Ramgopal S, Janofsky S, Zuckerbraun NS, Ramilo O, Mahajan P, Kuppermann N, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in infants aged </=60 days presenting to emergency departments with a history of fever only. J Pediatr. 2019;204:191–5.

Craig JC, Williams GJ, Jones M, Codarini M, Macaskill P, Hayen A, et al. The accuracy of clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of serious bacterial infection in young febrile children: prospective cohort study of 15 781 febrile illnesses. BMJ. 2010;340:c1594.

Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1437–41.

Baskin MN, O'Rourke EJ, Fleisher GR. Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. J Pediatr. 1992;120(1):22–7.

Dagan R, Sofer S, Phillip M, Shachak E. Ambulatory care of febrile infants younger than 2 months of age classified as being at low risk for having serious bacterial infections. J Pediatr. 1988;112(3):355–60.

Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, White KC, Fisher DJ, Dagan R, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection--an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics. 1994;94(3):390–6.

Aronson PL, McCulloh RJ, Tieder JS, Nigrovic LE, Leazer RC, Alpern ER, et al. Application of the Rochester criteria to identify febrile infants with bacteremia and meningitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(1):22–7.

Garra G, Cunningham SJ, Crain EF. Reappraisal of criteria used to predict serious bacterial illness in febrile infants less than 8 weeks of age. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(10):921–5.

Huppler AR, Eickhoff JC, Wald ER. Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):228–33.

Irwin AD, Wickenden J, Le Doare K, Ladhani S. Supporting decisions to increase the safe discharge of children with febrile illness from the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(3):259–66.

Blaser MJ. Antibiotic use and its consequences for the normal microbiome. Science. 2016;352(6285):544–5.

Paz Z, Lieber SB, Moore A, Zhu C, Fowler ML, RH S. The impact of prior antibiotic treatment on culture results of patients with septic arthritis: abstract number: 1345. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67:1702–3.

Scheer CS, Fuchs C, Grundling M, Vollmer M, Bast J, Bohnert JA, et al. Impact of antibiotic administration on blood culture positivity at the beginning of sepsis: a prospective clinical cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(3):326–31.

Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):595–610.

Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):311–6.

Levine DA, Platt SL, Dayan PS, Macias CG, Zorc JJ, Krief W, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1728–34.

Aronson PL, Wang ME, Shapiro ED, Shah SS, DePorre AG, McCulloh RJ, et al. Risk stratification of febrile infants </=60 days old without routine lumbar puncture. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181879.

Shah S, Mathews B, Neuman MI, Bachur R. Detection of occult pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(9):615–21.

Vaz LE, Kleinman KP, Raebel MA, Nordin JD, Lakoma MD, Dutta-Linn MM, et al. Recent trends in outpatient antibiotic use in children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):375–85.

Petersen I, Johnson AM, Islam A, Duckworth G, Livermore DM, Hayward AC. Protective effect of antibiotics against serious complications of common respiratory tract infections: retrospective cohort study with the UK general practice research database. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):982.

Farah R, Lahoud N, Salameh P, Saleh N. Antibiotic dispensation by Lebanese pharmacists: a comparison of higher and lower socio-economic levels. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(1):37–46.

Khalifeh MM, Moore ND, Salameh PR. Self-medication misuse in the Middle East: a systematic literature review. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2017;5(4):e00323.

Bochner RE, Gangar M, Belamarich PF. A clinical approach to tonsillitis, tonsillar hypertrophy, and peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscesses. Pediatr Rev. 2017;38(2):81–92.

Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, Alverson B, Carter ER, Harrison C, et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25–76.

Siddiq S, Grainger J. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media: American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines 2013. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2015;100(4):193–7.

Chamoun K, Farah M, Araj G, Daoud Z, Moghnieh R, Salameh P, et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Lebanese hospitals: retrospective nationwide compiled data. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;46:64–70.

Cheaito L, Azizi S, Saleh N, Salameh P. Assessment of self-medication in population buying antibiotics in pharmacies: a pilot study from Beirut and its suburbs. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(2):319–27.

Kabbara WK, Meski MM, Ramadan WH, Maaliki DS, Salameh P. Adherence to international guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in Lebanon. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:7404095.

Chehayeb H. Antimicrobial Stewardship: where we stand. HUMAN & HEALTH | N°37 - Autumn. 2016:48–52. https://syndicateofhospitals.org.lb/Content/uploads/SyndicateMagazinePdfs/4953_48-53.pdf.

Haddad N, Kanj SS, Awad LS, Abdallah DI, Moghnieh RA. The 2018 Lebanese Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology Guidelines for the use of antimicrobial therapy in complicated intra-abdominal infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):293.

Husni R, Atoui R, Choucair J, Moghnieh R, Mokhbat J, Tabbarah Z, et al. The Lebanese Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology Guidelines for the treatment of urinary tract infections. Leban Med J. 2017;65(4):208–19.

Lebanon. 2019. Update 2019 [1/12/2020]. Available from: https://apua.org/lebanon. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Cynthia Wakim and Dr. Adonis Wazir for final references and edits.

Funding

Not funding was used for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS supervised the design and execution of the study, had primary responsibility for protocol development, analytical framework for the study, outcome assessment, data analysis and writing the manuscript. MM and HT had primary responsibility for protocol development, analytical framework for the study, outcome assessment, data analysis and writing the manuscript. SS participated in the protocol development, data collections and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TEZ, SM, SAM and CEAH participated in the data collection, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. MM participated in the data analysis and writing of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval from the American University of Beirut was obtained. UB IRB Protocol Number: PED.MM1.05.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawaya, R.D., El Zahran, T., Mrad, S. et al. Comparing febrile children presenting on and off antibiotics to the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 20, 117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-2007-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-2007-4