Abstract

Background

India introduced rotavirus vaccines (RVV, monovalent, Rotavac™ and pentavalent, Rotasiil™) in April 2016 with 6, 10 and 14 weeks schedule and expanded countrywide in phases. We describe the epidemiology of intussusception among children aged 2–23 months in India.

Methods

The prospective surveillance at 19 nationally representative sentinel hospitals from four regions recruited children with intussusception from April 2016 to September 2017. Data on sociodemography, immunization, clinical, treatment and outcome were collected. Along with descriptive analysis, key parameters between four regions were compared using Chi-Square/Fisher’s exact/Mann–Whitney U/Kruskal-Wallis tests. The pre- and post-RVV periods were compared to estimate the risk ratios.

Results

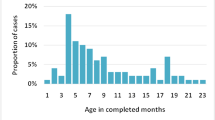

Six hundred twenty-one children with intussusception from South (n = 262), East (n = 190), North (n = 136) and West (n = 33) regions were recruited. Majority (n = 465, 74.8%) were infants (40.0% aged 4–7 months) with median age 8 months (IQR 5, 13 months), predominantly males (n = 408, 65.7%) and half (n = 311, 50.0%) occurred during March–June months. A shorter interval between weaning and intussusception was observed for ragi based food (median 1 month, IQR 0–4.2 months) compared to rice (median 4 months, IQR 1–9 months) and wheat (median 3 months, IQR 1–7 months) based food (p < 0.01). Abdominal pain or excessive crying (82.8%), vomiting (72.6%), and bloody stool (58.1%) were the leading symptoms. Classical triad (abdominal pain, vomiting and bloody stool) was observed in 34.8% cases (24.4 to 45.8% across regions). 95.3% of the cases were diagnosed by ultrasound. 49.3% (10.5 to 82.4% across regions) cases were managed by reduction, 39.5% (11.5 to 71.1% across regions) cases underwent surgery and 11.1% spontaneously resolved. Eleven (1.8%) cases died. 89.1% cases met Brighton criteria level 1 and 7.6% met Level 2. RVV was received by 12 cases within 1–21 days prior to intussusception. No increase in case load (RR = 0.44; 95% CI 0.22–1.18) or case ratio (RR = 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–1.2) was observed after RVV introduction in select sites.

Conclusions

Intussusception cases were observed across all sites, although there were variations in cases, presentation and mode of management. The high case load age coincided with age of the RVV third dose. The association with ragi based weaning food in intussusception needs further evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

To reduce the rotavirus diarrhoea related childhood deaths, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended introduction of rotavirus vaccine (RVV) in national immunization programmes (NIPs). Some increased risk of intussusception after the first (relative risk, RR: 4.7–13.8) and second (RR: 1.3–5.3) doses of RVVs was reported from several countries (Mexico, Brazil, Australia, United Kingdom, United States, Spain and Singapore) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. But no increased risk of intussusception after any dose of RVV was observed in some countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa) [9, 10]. The impact of RVV on diarrhoea morbidity and mortality outweigh the risk of intussusception and associated mortality [11]. In view of the concern about intussusception, documentation of baseline and monitoring following RVV introduction have been recommended [12]. India introduced RVV into the NIP in April 2016 and by 2019 expanded countrywide in four phases [13]. Two types of RVV are used in NIP, Rotavac™ (RV1-116E; Bharat Biotech) in 26 states/union territories and Rotasill™ (RV5; Serum. Institute of India) in 11 states/union territories, both follow 6, 10, 14 weeks schedule. Intussusception is an acute severe clinical condition occurring mostly during infancy, which overlaps with the age of primary vaccinations. The nationally representative background epidemiology of intussusception in India is not clear. The reports from India primarily included retrospective data and considerably varied in the epidemiology, presentation and management [14, 15]. Information on population level rate in India is limited and the reported incidences of intussusception requiring hospitalization varied from 17.7 (95% CI 5.9–41.4) in Delhi (North India) to 254 (95% CI 102, 524) cases per 100,000 child-years in Vellore (South India) [16, 17]. The incidence of intussusception vary widely globally, across the different high and low-middle income countries [18]. The reasons for the variations are unknown. There is no information from India regarding the regional variation in intussusception epidemiology. Thus, documentation of the intussusception epidemiology prior to RVV introduction to establish a reliable baseline for monitoring the trend over time and identify potential risk factors was needed to support the vaccine safety surveillance efforts [19, 20]. Under the vaccine safety surveillance effort, we describe the epidemiology, clinical characteristics of intussusception among children aged under-2 years seeking hospital care in India and initial changes with RVV introduction documented through a nationally representative sentinel surveillance network.

Methods

Study area and participating hospitals

This prospective active hospital-based sentinel surveillance was conducted over 18 months, at 19 nationally representative tertiary care hospitals (Supplementary Figure 1). From the four regions, 3–6 hospitals per region including medical colleges and private-sector hospitals (North region- 5 sites, 3 public and 2 private; South region- 5 sites, 2 public and 3 private; East region- 6 sites, 5 public and 1 private; West region- 3 sites, 2 public and 1 private) were selected through a systematic process. Out of these sites, four sites were located in the states where RVV was introduced in April 2017 under phase 1. At all sites the RVVs were available in private market during the study period, even prior to the introduction in NIP.

Case definition, case selection and data collection

The children aged 2–23 months admitted to these hospitals with diagnosis of intussusception were eligible. All the age-eligible patients admitted were screened to identify the suspected cases (any of the diagnoses: intussusception, acute or subacute intestinal obstruction, acute abdomen, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and blood in stool with vomiting). These suspected cases were tracked till final diagnosis and all confirmed intussusception cases were recruited after written informed consent from parent or legally authorised representative. A log of screened, suspected and confirmed cases was maintained. The data on socio-demography, feeding and immunization (from immunization card), clinical features, investigation findings, hospital course, treatment and outcome were collected using common case record form (CRF). The symptoms were captured as recorded in the case sheets and reported by the parents. An independent Case Adjudication Committee (CAC) comprised of a paediatrician, paediatric surgeon, and radiologist reviewed the CRFs and investigations to assign the diagnostic certainty levels, according to Brighton Collaboration case definition (BCCD) [21].

Quality assurance

Multilevel quality assurance and data quality-checking processes were put in place to ascertain protocol adherence, rigor and completion of surveillance at all sites. A data team reviewed all the CRFs and data-related query was resolved at the earliest. Each site was visited by external experts (Technical Advisory Group, TAG) to assess the case surveillance and tracking, consent, and data extraction quality and completeness in the CRFs. The TAG members checked CRFs completeness and quality for few randomly identified cases with the case records. Subsequently members from the data team visited the study sites and checked the admissions for the study period from the medical records section using diagnoses and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (ICD-9/10, codes listed in Supplementary Table 1), to identify any missed cases.

Data management and analysis

Double data entry was done for the CRFs using a customised data entry platform. The matched and verified data were stored in the server with authorised access and daily backup. The standard of living index (SLI), representing the socioeconomic status was estimated using the scores for household assets ownership, with reference to the National Family and Health Survey for India [22]. The SLI was categorised into high, medium and low categories. The cases were categorised into levels 1 to 3 based on the BCCD criteria by the CAC [21]. In view of the number of sites, for representation we grouped the sites into four regions, North (5 sites), South (5 sites), East (6 sites) and West (3 sites) regions. The parameters (sociodemographic, feeding, clinical, intervention and outcomes were compared between the regions to detect variations. The intussusception classical triad includes three features; abdominal pain, vomiting and blood in stools. We considered intussusception modified triad with abdominal pain, vomiting and rectal bleeding, detected either as blood in stool or blood on per-rectal examination. The descriptive analysis findings expressed the outputs as proportions, means and standard deviations, or median and interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. The values between regions and groups were compared for statistical significance using Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact tests for the proportions and Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests for the medians depending on the skewness, sample and number of groups. The missing data were excluded from analysis. The statistical significance was considered if p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA). In the Indian context, there is no definite population catchment area for hospitals and no definite referral chain, which makes estimation of the intussusception incidence difficult. For comparison of the data across sites and intussusception time trend, in addition to case load (absolute number of cases), we attempted deriving the intussusception case rate per 1000 paediatric hospitalisations at the hospitals. On review, while the admission numbers in the paediatric medicine wards varied widely, the admission numbers in the paediatric surgery wards were relatively stable and the intussusception cases were primarily managed in the paediatric surgery wards. Thus we estimated the intussusception case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admissions at these hospitals for comparison and trend analysis. For the four sites in three states (Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Haryana), where RVV (monovalent Rotavac™, 3 doses at 6, 10, 14 weeks age) was introduced under NIP (in April 2017), the data for the post-introduction period (April to September 2017, 6 months) was compared with the pre-introduction periods (first: October 2016 to March 2017, immediate 6 months pre-introduction period and second: April 2016 to September 2016, calendar matched 6 months during the previous year) to document the risk ratio (95% confidence interval, CI). The detailed methodology of the site selection and study implementation has been published as protocol [23].

Ethical issues

Informed written consent was obtained for all the eligible cases before recruitment and data collection. Confidentiality in data handling was maintained. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees of all participating institutes.

Results

Between April 2016 and September 2017, out of the 182,824 children (including 32,910 paediatric surgery admissions) admitted to the network hospitals, 1203 suspected intussusception cases were identified and 621 eligible children were recruited (Supplementary Figure 2). More cases were recruited from Southern region (42.2%; 262/621) followed by East (30.6%; 190/621), North (21.9%; 136/621) and West (5.3%; 33/621) regions. Past history of intussusception was present in 24 (3.8%) cases. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of children with intussusception. A male predominance (male-female ratio: 1.9:1) was consistent across all regions. The median age at presentation was 8 months (IQR 5, 13 months) (Supplementary Figure 3). Three quarters of the cases were infants with equal share from the age bands of 2–6 months (37.2%) and 7–12 months (37.7%) (p < 0.01). Children aged 4–7 months contributed to 40.0% of the total cases. The pooled intussusception case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admission was 18.4 (IQR 14.7, 23.4). The intussusception case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admission was highest for South (25.3, IQR 23.4, 32.7) followed by North (14.5, IQR 11, 19.7), East (13.8, IQR 10.5, 22) and West (6.6, IQR 1.2, 19.2) regions respectively. The Fig. 1 shows monthly trends of pooled intussusception case load and case rates per 1000 paediatric surgery admission (Fig. 1a) and the regional case rates per 1000 paediatric surgery admission (Fig. 1b). More cases (n = 311, 50.0%) were seen during March to June months, in the summer season (Fig. 1). While 42.8% of the patients were resident of the same district where the hospital was based, 41.9% of the patients presented directly to the hospital. Among the children aged > 6 months, 23.2% were exclusively breastfed for 6 months and the median duration of breastfeeding was 4 months. Mixed feeding was initiated before 6 months of age in 53.9% children. The median weaning age was 6 months and 61.0% received rice based food. Ragi (finger millet) was given to 22.8% children, only in the South region. The interval between weaning and intussusception was significantly shorter for ragi (median 1 month, IQR 0–4.2 months) than rice (median 4 months, IQR 1–9 months) and wheat (median 3 months, IQR 1–7 months) based food (Table 1) (p < 0.01). On analysis for the South region only (where ragi based weaning practice was observed), the median interval between weaning and intussusception for ragi based food was significantly shorter (median 1 month, IQR 0–4 months) than rice (median 5 months, IQR 2–9 months) and wheat (median 3 months, IQR 2–8 months) based food (p < 0.01).

The pooled median interval between the onset to hospital admission was 2 days (IQR 1, 3), which varied across the regions; North- 2 days (IQR 1, 3), South- 1 day (IQR 1, 3), East- 2 days (IQR 1, 3) and West- 2 days (IQR 1, 2) (p = 0.07). Table 2 summarises the clinicopathological parameters and management for the recruited children. Abdominal pain or excessive crying (82.6%) was the most common symptom followed by vomiting (72.6%) and blood in stool (58.1%), as reported by the parents. More children had abdominal pain or excessive crying in North (84.6%) and East (72.6%) regions and blood in stool in the East region (73.2%). The classical triad (abdominal pain, vomiting and blood in stool) was observed in 34.8% cases, with 24.4 and 45.8% in the South and in East regions, respectively (p < 0.01). When blood on per-rectal examination was included, the modified intussusception triad (abdominal pain, vomiting and blood in stool or blood on per-rectal examination) was present in 59.9% cases; 47.7% in South to 75.3% in East regions (p < 0.01).

Most of the cases (95.3%) were diagnosed by ultrasound. Ileocolic (84.7%) was the most common site of intussusception. A pathological lead point (PLP) was documented in 91 (14.6%) cases and lymph nodes or Payer’s patch were the commonest (13.0%) and few had appendix or polyps (Table 2). While 49.3% cases were reduced, 39.5% underwent surgery and 11.1% resolved spontaneously. More children in East region (71.1%) underwent surgery followed by North region (50.0%) (p < 0.01). Among those who underwent surgery, 26.1% children required bowel resection, and 39.5% were from the North region. The onset-admission interval was longer for the cases who underwent surgery (median 2 days; IQR 1, 3) than reduction (median 1 day; IQR 1, 3) (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Table 2). Among the children who presented on the day of onset, 62.3% were managed by reduction (28.9% required surgery), which declined to 35.1% when they presented after 3 days (48.3% required surgery) (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Table 2). Seven hospitals (East-1, North-1, and South-1) were conducting only surgical management. At the hospitals with both facilities (reduction and surgery), 31.0% (127/404) children underwent surgery for indications: failed reduction (32.2%), late presentation (> 3 days since onset, 28.3%) and associated complications (39.3%) (p < 0.01). Most of the cases (97.1%) recovered and were discharged. Eleven cases (North-4 and East-7) died of post-surgery sepsis, shock and multiorgan failure. The median hospitalisation period was 3 days (IQR 2, 6 days) ranging from 2 to 5 days (South: 2 days, IQR 2, 3 days; North: 3 days, IQR 1, 7 days; West: 4 days, IQR 2, 6 days; and East: 5 days, IQR 3, 8 days; p < 0.01). The median hospital stay periods for children who underwent surgery, reduction and spontaneously resolved were 7 days (IQR 5, 9 days), 2 days (IQR 1, 2 days) and 3 days (IQR 2, 5 days), respectively (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Table 2). CAC assigned 89.1% (553/621) and 7.6% cases as Level 1 and 2 respectively according to the BCCD. Diarrhoea and acute respiratory illnesses (ARIs) within 4 weeks prior to intussusception was reported in 12.9 and 23.7% children respectively. More children from South region had history of diarrhoea (21%) and ARIs (39.7%) than other regions (p < 0.05).

Vaccination information was available for 487 (78.4%) children and 391 (80.2%) of those with vaccination information had no RVV exposure. Out of 96 (15.4%) children who received any RVV (RVV-1, n = 96; RVV-2, n = 88; and RVV-3, n = 65), 12 children received RVV in the 1–21 days preceding onset of intussusception and most (n = 10) after RVV-3 (median age 3.8 months, IQR 3.6, 4.2 months) (Supplementary Table 3). As shown in Fig. 2, only two cases occurred during 1–7 days after the third dose RVV and one case occurred on the vaccination day. At the four sites from three states where RVV (Rotavac™) was introduced, no increase in either intussusception case load (RR = 0.44; 95% CI 0.22, 1.18) or case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admission (RR = 0.5; 95% CI 0.3, 1.2) during the post-RVV introduction period were observed (Table 3).

Discussion

We observed regional variances in the intussusception case load and case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admission, high in the South region and low in the West region. Higher number of cases were observed during March to June months, which was comparable to other reports from India [14, 15, 17, 24, 25]. The male predominance (65.7%), median age at 8 months and high case load at 4–7 months of age (40.0%) were similar to other reports from India and globally (proportion of male: 63.0–77.2%; median age: 5–8 months and high case load age: 4–9 months) [14, 15, 17, 18, 21, 24, 26, 27]. About 37.0% of cases occurred during 2nd to 6th month of age, the usual age for administration of RVV. The children came from all socioeconomic categories and in all the regions. The proportion of exclusively breastfed children (< 6 months) was lower than national average (52.1%, 2015–16) [22]. The children weaned with ragi food (only in South region) had intussusception earlier (median 1 month) than those weaned with wheat (median 3 months) and rice (median 4 months) based food. A shorter exclusive breastfeeding duration with mixed feeding and some weaning foods may have some role in intussusception occurrence. Exposure to foreign proteins and enteric infections are potential risk factors for intussusception, but we couldn’t find any report on association with any specific diet. There were significant variations for several sociodemographic and dietary practice parameters across the regions (Table 1). The classical triad was documented in 34.8% cases, which was higher than reports from India (19.0%) and South Korea (7.6%), but lower than Tanzania (42.5%) [15, 24, 28]. The regional variation in the classical triad appeared to parallel with the interval between illness onset and hospitalization. Ultrasound was the commonest (95.3%) mode of diagnosis, as reported (72.0–100%) from India and other countries [15, 18, 28,29,30]. Ileocolic was the most common location, similar to reports (68.0–79.0%) from India and globally [3, 7, 8, 14]. PLPs observed in this study was higher than reported in studies (8.0–9.0%) from India and Tanzania with appendix and lymph nodes as the common [31, 32]. The cases who presented early were more frequently managed non-surgically with shorter stay (2–3 days) compared to those with surgical intervention (7 days). There were significant variations in the clinical features among the children across the regions, which may be due to the interval for presentation or clinical practices followed at the hospitals (Table 2). Death was observed in 1.7% cases, which was comparable to reports from India (1.0%) and other countries from Asia (0.25–6.0%), Latin America (1.0–5.0%), but lower than the African countries (2.0–25.0%) [17, 18, 24, 28, 29, 31,32,33]. Level 1 BCCD was met by 89.1% of the cases, similar to other reports from India [5, 7, 14]. Failed documentation of reduction prevented some cases meeting the BCCD level 1 certainty.

From the limited period of post-RVV (Rotavac™) introduction at four sites (from three states), no increase in the intussusception case load and case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admission were observed. Intussusception within 1–21 days was observed mostly after the third RVV dose, which also overlaps with the age of natural occurrence. Under the NIP, RVV is given at 6, 10, 14 weeks of age and allowed before 12 months of age [34]. A delay in RVV administration may coincide with the high case load age of natural intussusception (4–7 months age), which may make the interpretation of association with the vaccine difficult. In routine practice, documentation of vaccine exposure should improve and appropriate guidance to parents be given regarding the subsequent RVV vaccination. Monitoring of intussusception risk is recommended for countries as part of the RVV introduction program [35, 36]. In the absence of any specific population denominator for tertiary care hospitals, estimation of incidence in Indian context is difficult. The intussusception case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admissions may be a proxy indicator for monitoring and comparison across the sites and regions with RVV introduction.

Early suspicion, case detection and referral to appropriate hospital are critical for minimizing the surgical interventions and favourable outcomes. Efforts are needed to equip and enable the public health facilities for non-surgical management in children, though this depends on the timing of the presentation to hospital.

The epidemiology, clinical presentation and management of intussusception in children across the regions may serve as baseline for future studies. The regional representation and mix of private- and public-sector hospitals were the advantages for this surveillance.

This study had some limitations. In absence of definite catchment population and referral pattern, population-based incidence or case rate estimation was not possible. The etiologies and risk factors for intussusception were not studied.

Conclusion

To conclude, the intussusception cases were seen all across the country and the majority of the cases occurred during the first year of life. The high case load age (4–7 months) for intussusception in children coincided with the age of RVV third dose. Some variations in case loads across the different regions and seasonality were observed. The potential role of diet exposure, weaning practices and food like ragi in intussusception needs further evaluation. No increased occurrence of intussusception cases was observed during the limited RVV post-introduction period. Early case detection, prompt referral and appropriate management are needed to avoid surgical intervention and complications. Immunization exposure must be documented to assess the vaccine associated risk. In absence of population-based incidence or case rate, the intussusception case rate per 1000 paediatric surgery admission may be used for inter-regional comparison and trend monitoring.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available with the investigators and can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CRF:

-

Case record form

- CAC:

-

Case Adjudication Committee

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- TAG:

-

Technical Advisory Group

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- RVV:

-

Rotavirus vaccine

- SLI:

-

Standard of living index

- NIP:

-

National immunization programmes.

References

Patel MM, López-Collada VR, Bulhões MM, De Oliveira LH, Márquez AB, Flannery B, et al. Intussusception risk and health benefits of rotavirus vaccination in Mexico and Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(24):2283–92.

Velázquez FR, Colindres RE, Grajales C, Hernández MT, Mercadillo MG, Torres FJ, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of intussusception following mass introduction of the attenuated human rotavirus vaccine in Mexico. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(7):736–44.

Carlin JB, Macartney KK, Lee KJ, Quinn HE, Buttery J, Lopert R, et al. Intussusception risk and disease prevention associated with rotavirus vaccines in Australia’s National Immunization Program. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(10):1427–34.

Yih WK, Lieu TA, Kulldorff M, Martin D, McMahill-Walraven CN, Platt R, et al. Intussusception risk after rotavirus vaccination in U.S. infants. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):503–12.

Weintraub ES, Baggs J, Duffy J, Vellozzi C, Belongia EA, Irving S, et al. Risk of intussusception after monovalent rotavirus vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):513–9.

Stowe J, Andrews N, Ladhani S, Miller E. The risk of intussusception following monovalent rotavirus vaccination in England: a self-controlled case-series evaluation. Vaccine. 2016;34(32):3684–9.

Yung C-F, Chan SP, Soh S, Tan A, Thoon KC. Intussusception and monovalent rotavirus vaccination in Singapore: self-controlled case series and risk-benefit study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(1):163–168.e1.

Pérez-Vilar S, Díez-Domingo J, Puig-Barberà J, Gil-Prieto R, Romio S. Intussusception following rotavirus vaccination in the Valencia region, Spain. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2015;11(7):1848–52.

Tate JE, Mwenda JM, Armah G, Jani B, Omore R, Ademe A, et al. Evaluation of intussusception after monovalent rotavirus vaccination in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1521–8.

Groome MJ, Tate JE, Arnold M, Chitnis M, Cox S, de Vos C, et al. Evaluation of intussusception after oral monovalent rotavirus vaccination in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(8):1606–12.

Yen C, Tate JE, Hyde TB, Cortese MM, Lopman BA, Jiang B, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: current status and future considerations. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10(6):1436–48.

World Health Organization. Post-marketing surveillance of rotavirus vaccine safety. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70017/WHO_IVB_09.01_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Press Informationn Beureau. Shri J P Nadda launches Rotavirus vaccine as part of Universal Immunization Programme; terms it a “historic moment”: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India; 2016. [cited 2019 Jan 10]. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=138342.

Bhowmick K, Kang G, Bose A, Chacko J, Boudville I, Datta SK, et al. Retrospective surveillance for intussusception in children aged less than five years in a south Indian tertiary-care hospital. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(5):660–5.

Singh JV, Kamath V, Shetty R, Kumar V, Prasad R, Saluja T, et al. Retrospective surveillance for intussusception in children aged less than five years at two tertiary care centers in India. Vaccine. 2014;32:A95–8.

Bahl R, Saxena M, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Mathur M, Parashar UD, et al. Population-based incidence of intussusception and a case-control study to examine the association of intussusception with natural rotavirus infection among Indian children. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(s1):S277–81.

Jehangir S, John J, Rajkumar S, Mani B, Srinivasan R, Kang G. Intussusception in southern India: comparison of retrospective analysis and active surveillance. Vaccine. 2014;32:A99–103.

Jiang J, Jiang B, Parashar U, Nguyen T, Bines J, Patel MM. Childhood intussusception: a literature review. Cameron DW, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68482.

World Health Organisation. Rotavirus vaccines WHO position paper: January 2013 - Recommendations. Vaccine. 2013;31(52):6170–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.037.

Tate JE, Steele AD, Bines JE, Zuber PLF, Parashar UD. Research priorities regarding rotavirus vaccine and intussusception: a meeting summary. Vaccine. 2012;30:A179–84.

Bines JE, Kohl KS, Forster J, Zanardi LR, Davis RL, Hansen J, et al. Acute intussusception in infants and children as an adverse event following immunization: case definition and guidelines of data collection, analysis, and presentation. Vaccine. 2004;22(5–6):569–74.

International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2017. [cited 2019 Apr 10]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/data/bh/bhchap2.pdf.

Das M, Arora N, Bonhoeffer J, Zuber P, Maure C. Intussusception in young children: protocol for multisite hospital sentinel surveillance in India. Methods Protoc. 2018;1(2):11.

Srinivasan R, Girish Kumar CP, Naaraayan SA, Jehangir S, Thangaraj JWV, Venkatasubramanian S, et al. Intussusception hospitalizations before rotavirus vaccine introduction: retrospective data from two referral hospitals in Tamil Nadu, India. Vaccine. 2018;36(51):7820–5.

Gupta M, Kanojia R, Singha R, Tripathy JP, Mahajan K, Saxena A, et al. Intussusception rate among under-five-children before introduction of rotavirus vaccine in North India. J Trop Pediatr. 2018;64(4):326–35.

Patel MM, Clark AD, Sanderson CFB, Tate J, Parashar UD. Removing the age restrictions for rotavirus vaccination: a benefit-risk modeling analysis. von Seidlein L, editor. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):e1001330.

Bhandari N, Rongsen-Chandola T, Bavdekar A, John J, Antony K, Taneja S, et al. Efficacy of a monovalent human-bovine (116E) rotavirus vaccine in Indian infants: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2136–43.

Jo DS, Nyambat B, Kim JS, Jang YT, Ng TL, Bock HL, et al. Population-based incidence and burden of childhood intussusception in Jeonbuk Province, South Korea. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(6):e383–8.

Phua KB, Lee B-W, Quak SH, Jacobsen A, Teo H, Vadivelu-Pechai K, et al. Incidence of intussusception in Singaporean children aged less than 2 years: a hospital-based prospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):161.

Mansour AM, El Koutby M, El Barbary MM, Mohamed W, Shehata S, El Mohammady H, et al. Enteric viral infections as potential risk factors for intussusception. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(01):028–35.

Raman T, Mukhopadhyaya A, Eapen CE, Aruldas V, Bose A, Sen S, et al. Intussusception in southern Indian children: lack of association with diarrheal disease and oral polio vaccine immunization. Indian J Gastroenterol Off J Indian Soc Gastroenterol. 2003;22(3):82–4.

Chalya PL, Kayange NM, Chandika AB. Childhood intussusceptions at a tertiary care hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in resource-limited setting. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40(1):28.

Tagbo BN, Mwenda J, Eke C, Oguonu T, Ekemze S, Ezomike UO, et al. Retrospective evaluation of intussusception in under-five children in Nigeria. World J Vaccines. 2014;04(03):123–32.

Immunization Division. Operational Guidelines- Introduction of Rotavirus Vaccine in the Universal Immunization Program in India. Revised March 2019. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Immunization/Guildelines_for_immunization/Operational_Guidelines_for_Introduction_of_Rotavac_in_UIP.pdf. [cited 2019 Jun 16].

World Health Organisation. Post-marketing surveillance of rotavirus vaccine safety. [cited 2017 Sep 18]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70017/1/WHO_IVB_09.01_eng.pdf.

Mwenda JM, Tate JE, Steele AD, Parashar UD. Preparing for the scale-up of rotavirus vaccine introduction in Africa: establishing surveillance platforms to monitor disease burden and vaccine impact. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:S1–5.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India for undertaking the study. We are thankful to the hospital administrations and the clinicians at the study site institutes, who supported and facilitated conduct of the study.

We highly value the technical guidance and inputs provided by the members of Technical Advisory Group: Satinder Aneja, Anju Seth and Archana Puri, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi; Ashok Patwari, Hamdard Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, New Delhi; Yogesh Kumar Sarin, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi; Rakesh Aggarwal, Anshu Srivastava and Ujjal Poddar, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow; Malathi Satyasekharan, Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital, Chennai; Raju Sharma and Nirupam Madan, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi; Jyoti Joshi and Deepak Polpakara, Immunization Technical Support Unit; Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, New Delhi; Umesh D. Parashar; Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA; Naveen Thacker, Child Health Foundation, Gandhigram; and Rashmi Arora, Indian Council of Medical Research, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi.

We acknowledge the contribution of the research staffs at The INCLEN Trust International:

Harshpreet Kaur, Janvi Chaubey, Mrinmaya Das, Shweta Sharma and Vaibhav Jain.

We highly appreciate the efforts made by the research staffs at the study sites: Aarezo Bashir and Rafia; Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir; Prabha Shankar, Medanta-The Medicity Hospital, Gurgaon, Haryana; Anju Sharma; Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi; Anita Singh and Shubhranshu Srivastava, King George Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh; Hemant Meena, Choithram Hospital, Indore, Madhya Pradesh; Pankaj Kumar and Shashi Kant; Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar; Goutam Benia, IMS & SUM Medical College & Hospital, Bhubaneshwar, Odisha; Prasantajyoti Mohanty, SVP Post Graduate Institute of Paediatrics and SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha; Angshuman Chatterjee, Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research & SSKM Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal; S. Yamuna, Andhra Medical College, Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh; Srinidhi Sudam, Apollo Hospitals, Hyderabad, Telengana; Rajesh Francis, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, Tamil Nadu; T. Easter Chandru, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu; Deepthy R, Julie and Anju Shivakumar, Government Medical College & SAT Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala; Archit Vaidya, Grant Medical College & JJ Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra; Nimesh Chouksey, MP Shah Government Medical College, Jamnagar, Gujarat; Nidhi Singh, Fortis Escorts Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan; Mrinmoy Gohain, Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati, Assam; Arpita Bhattachrjee, Saugat Ghosh and Tanusmita Debnath, Agartala Government Medical College, Agartala, Tripura.

‘The INCLEN Intussusception Surveillance Network Study Group’ list of authors

-

1.

Manoja Kumar Das

Director Projects, The INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi, India

Email: manoj@inclentrust.org

-

2.

Narendra Kumar Arora

Executive Director, The INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi, India

Email: nkarora@inclentrust.org

-

3.

Bini Gupta

Assistant Research Officer, The INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi, India

Email: drbini.gupta02@gmail.com

-

4.

Apoorva Sharan

Research Officer, The INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi, India

Email: apoorva@inclentrust.org

-

5.

Mahesh K. Aggarwal

Deputy Commissioner-Immunization, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, India

Email: drmkagarwal2@gmail.com

-

6.

Pradeep Haldar

Deputy Commissioner-Immunization, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, India

Email: pradeephaldar@yahoo.co.in

-

7.

Patrick L F Zuber

Group Leader Global Vaccine Safety and Vigilance Team, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Email: zuberp@who.int

-

8.

Jan Bonhoeffer

President; Brighton Collaboration Foundation and Assistant Professor; Infectious Diseases and Vaccines, University Children’s Hospital, Basel, Switzerland

Email: jan.bonhoeffer@gmail.com

-

9.

Arindam Ray

Senior Program Officer, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, India Country Office, New Delhi, India

Email: arindam.ray@gatesfoundation.org

-

10.

Ashish Wakhlu

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

Email: ashish_wakhlu@hotmail.com

-

11.

Bhadresh R. Vyas

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, MP Shah Government Medical College, Jamnagar, Gujarat, India

Email: bhadreshrvyas@yahoo.co.uk

-

12.

Javeed Iqbal Bhat

Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir, India

Email: drjaveediqbal@gmail.com

-

13.

Jayanta K. Goswami

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati, Assam, India

Email: jayantagoswami@hotmail.com

-

14.

John Mathai

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Email: psg_peds@yahoo.com

-

15.

Kameswari K.

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Andhra Medical College, Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India

Email: kameswari1956@gmail.com

-

16.

Lalit Bharadia

Consultant Paediatric Gastroenterologist, Fortis Escorts Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Email: lalitbharadia@gmail.com

-

17.

Lalit Sankhe

Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Grant Medical College & JJ Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Email: sankhelalit@yahoo.com

-

18.

Ajayakumar M.K.

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Government Medical College & SAT Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

Email: drajaykumarmk@gmail.com

-

19.

Neelam Mohan

Consultant Paediatrics Gastroenterology, Medanta—The Medicity, Gurgaon, Haryana, India

Email: drneelam@yahoo.com

-

20.

Pradeep K. Jena

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha, India

Email: drpkjena@gmail.com

-

21.

Rachita Sarangi

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, IMS & SUM Medical College & Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Email: rachitapaedia@gmail.com

-

22.

Rashmi Shad

Consultant Paediatrics, Choithram Hospital and Research Centre, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India

Email: drrashmishad@yahoo.com

-

23.

Sanjib K. Debbarma

Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Agartala Government Medical College, Agartala, Tripura, India

Email: dr_sanjibdb@rediffmail.com

-

24.

Shyamala J.

Consultant Paediatrics, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, Tamil Nadu

Email: jaymoorthy@hotmail.com

-

25.

Simmi K. Ratan

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College, Delhi, India

Email: drjohnsimmi@yahoo.com

-

26.

Suman Sarkar

Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Email: dr.sumansarkar@gmail.com

-

27.

Vijayendra Kumar

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India

Email: drvijayendrakr@rediffmail.com

-

28.

Yoga Nagender

Consultant Paediatric Surgery, Apollo Hospital, Hyderabad, Telengana, India

Email: yogimamidi@yahoo.com

-

29.

Anand P. Dubey

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Maulana Azad Medical College, Delhi, India

Email: Anand_dubey52@hotmail.com

-

30.

Atul Gupta

Consultant Paediatric Surgery, Fortis Escorts Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Email: atul.gupta1@fortishealthcare.com

-

31.

Bashir Ahmad Charoo

Professor, Department of paediatrics, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir, India

Email: charoobash@gmail.com

-

32.

Bikasha Bihary Tripathy

Associate Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, IMS & SUM Medical College & Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Email: bbtripathy.dr@gmail.com

-

33.

Cenita J. Sam

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Email: cenitasivamani@yahoo.com

-

34.

G. Rajendra Prasad

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Andhra Medical College, Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India

Email: dr.grajendraprasad@gmail.com

-

35.

Gowhar Nazir Mufti

Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir, India

Email: gowharmufti@yahoo.co.in

-

36.

Harish Kumar S.

Paediatrics Radiologist, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Email: drharishkumar.s@gmail.com

-

37.

Harsh Trivedi

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, MP Shah Government Medical College, Jamnagar, Gujarat, India

Email: trivediharsh@indiatimes.com

-

38.

Jimmy Shad

Consultant Paediatric Surgery, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Email: shadjimmy@yahoo.co.in

-

39.

K. Jothilakshmi

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Email: drjothi.cbe@gmail.com

-

40.

K. Sharmila

Consultant Paediatrics, Apollo Hospital, Hyderabad, Telengana, India

Email: sharmilakaza@gmail.com

-

41.

Kaushik Lahiri

Department of Paediatric Surgery, Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati, Assam, India

Email: Kaushik_1671979@rediffmail.com

-

42.

Meera Luthra

Consultant Paediatric Surgery, Medanta- The Medicity, Gurgaon, Haryana, India

Email: meera.luthra@medanta.org

-

43.

Nihar Ranjan Sarkar

Associate Professor, Department of Radiology, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Email: dr.niharsarkar@gmail.com

-

44.

P. Padmalatha

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Andhra Medical College, Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India

Email: padmap_2000@yahoo.com

-

45.

Pavai Arunachalam

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Email: pavai4321@yahoo.com

-

46.

Rakesh Kumar

Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India

Email: drjaiswalrakesh@gmail.com

-

47.

Ruchirendu Sarkar

Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Email: ruchirendu@gmail.com

-

48.

S.S.G. Mohapatra

Professor, Department of Radiology, IMS & SUM Medical College & Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Email: drartifact@gmail.com

-

49.

Santosh Kumar A.

Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Government Medical College & SAT Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

Email: hod.pediatrics.sath@gmail.com

-

50.

Saurabh Garge

Consultant Paediatric Surgery, Choithram Hospital and Research Centre, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India

Email: saurabhgarge8@gmail.com

-

51.

Subrat Kumar Sahoo

Associate Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, IMS & SUM Medical College & Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Email: dr_subratsahoo@yahoo.com

-

52.

Sunil K. Ghosh

Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Agartala Government Medical College, Agartala, Tripura, India

Email: sunilkrghosh752@gmail.com

-

53.

Sushant Mane

Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Grant Medical College & JJ Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Email: drsush2006@gmail.com

-

54.

Christine G. Maure

Safety and Vigilance Team, Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Email: maurec@who.in

Disclosure statement

None. There is no financial interest or benefit for the authors arisen from this project or its direct application.

Funding

This project was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, USA to The INCLEN Trust International (grant number OPP1116433). The funder or its representative had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Study conceptualisation, study design, protocol development, training, data analysis, interpretation: MKD and NKA. Study coordination, monitoring, and data cleaning: MKD, BG, and AS. Data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation: MKD and BG. Protocol development, quality assurance and monitoring: MKA, PH, PLFZ, JB, AR, and CGM. Participant recruitment and data collection: AW, BRV, JIB, JKG, JM, KK, LB, LS, AMK, NM, PKJ, RS-1, RS-2, SKD, SJ, SKR, SS, VK, YN, APD, AG, BBT, CJS, GRP, GNM, HKS, HT, JS, KJ, KS, KL, ML, NRS, PP, PA, RK, RS-3, SSGM, SKA, SG, SKS, SKG, and SM. All authors reviewed, provided critical input and approved the final version. The content represents the views of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the official positions of their organizations, World Health Organization or Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by The INCLEN Independent Ethics Committee, The INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi, India (Ref: IIEC 23) and all participating Study Site Institute Ethics Committees. The list of ethics committees of the study site institutes included: Institutional Ethics Committee, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, MP Shah Government Medical College, Jamnagar, Gujarat, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati, Assam, India; Institutional Human Ethics Committee, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, King George Hospital, Andhra Medical College, Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Fortis Escorts Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Grant Medical College & JJ Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Government Medical College & SAT Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India; Medanta Institutional Ethics Committee, Medanta—The Medicity, Gurgaon, Haryana, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, IMS & SUM Medical College & Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India; Institutional Ethics Committee; Choithram Hospital and Research Centre, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Agartala Government Medical College, Agartala, Tripura, India; Institutional Ethics Committee- Clinical Studies, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, Tamil Nadu; Institutional Ethics Committee, Maulana Azad Medical College, Delhi, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India; Institutional Ethics Committee, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India; and Ethics Committee, Apollo Hospital, Hyderabad, Telengana, India. The interviews with stakeholders were done after obtaining written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interests and conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary document 1- Supplementary Figure 1: The study sites and their locations according to the regions. Supplementary document 2- Supplementary Table 1: The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for review of the cases from medical records. Supplementary document 3- Supplementary Figure 2: The flow chart for case screening and recruitment. Supplementary document 4- Supplementary Figure 3: Age distribution of children with intussusception in India (region wise and pooled). Supplementary document 5- Supplementary Table 2: The mode of treatment according to the interval between onset, admission and intervention for the children with intussusception. Supplementary document 6- Supplementary Table 3: The intussusception cases during risk periods after rotavirus vaccine exposure.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

The INCLEN Intussusception Surveillance Network Study Group. Prospective surveillance for intussusception in Indian children aged under two years at nineteen tertiary care hospitals. BMC Pediatr 20, 413 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02293-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02293-5