Abstract

Introduction

Reducing neonatal mortality is an essential part of the third Sustainable Development Goal, to end preventable child deaths. Neonatal danger signs are the most common cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity. In Ethiopia, most babies are born at home or are discharged from the health institutions in the first 24 h, as a result enhancing women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs and its complication might reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the women knowledge towards neonatal danger signs in Ethiopia.

Method

MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, Hinari, Google scholar, web of science electronic databases and grey literature from repository were searched for all the available studies. Fourteen cross sectional studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Subgroup analysis was conducted for the evidence of heterogeneity. Cochrane I2 statistics were used to check the heterogeneity of the studies. Egger test with funnel plot were used to investigate publication bias.

Result

Fourteen cross-sectional studies with a total of 6617 study participants were included for this study. The overall pooled prevalence of women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger sign was 40.7% (95%CI, 25.72, 55.67). Having higher educational status of the women (AOR = 3.86, 95%CI: 2.3–6.5), having higher educational status of the husband (AOR = 4.57, 95%CI: 3.29–6.35), access to mass media (AOR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.17–2.23), having antenatal care visits (AOR = 2.63, 95%CI: 1.13–4.67), having postnatal care follow up (AOR = 2.55, 95%CI; 1.72–3.79) and giving birth at health institutions (AOR = 2.51, 95%CI:1.68–3.74) were factors associated with knowledge of the women towards danger sign of the neonate.

Conclusion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis the pooled prevalence of maternal knowledge towards neonatal danger sign was low. Educational status of the mother, educational status of the husband, access to mass media, antenatal care follow-up, postnatal care follow-up and place of delivery were factors associated with knowledge of the mother towards danger sign of the newborn. Promoting antenatal care, postnatal care follow-up and community-based health information dissemination about neonatal danger signs should be strengthened.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019132179.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neonates are the most vulnerable age group of the human population. They aren’t small adults, therefore they need to be regarded with special nursery and special care [1]. Neonatal danger signs are common and easy signs to recognize, associated with a potentially severe problem that can be easily identified by non-clinical personnel including the mother and other family members [2].

Women’s knowledge of neonatal danger sign is crucial to influence their decisions to seek immediate health care for their sick neonate who contributes a lot in reducing neonatal morbidity, mortality and related to disease presented with danger signs [3, 4]. Globally, 2.5 million neonates died during the neonatal period with approximately 7000 newborn deaths every day with about one third dying on the day of birth and near to three quarters dying within the first week of life accounting to 47% of all child deaths under the age of 5-years [5].

Worldwide, every year about four million babies die in the neonatal period (the first month of life) which accounts for 38% of all deaths in children younger than age 5 years. Despite, the number of neonatal deaths declined from 5 million in 1990 to 2.5 million in 2018 globally, decreasing neonatal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia is difficult to avert the significant burden of neonatal mortality [5,6,7].

Neonatal mortality rates were varying widely across the world, however the highest neonatal death occurred in 2018 Sub-Saharan Africa and Central and Southern Asia which accounts 28 and 25 deaths per 1000 live births respectively. If each country achieves the SDG neonatal mortality target of 12 deaths per 1000 live births or fewer by 2030, it was projected that 22.7 million cumulative neonatal deaths by 2030 [7, 8]. Neonatal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa or in Southern Asia are more than 10 times likely to die in the first month than a child born in developed countries. Majority of neonatal mortality in low and middle income countries happened at home in settings where a few women’s and family members recognize signs of newborn illness and nearly all neonates are not taken to health facilities when they were sick [7,8,9].

Nearly 75% of neonatal deaths could be avoided with simple low-cost effective methods if the neonate illness early recognized came to the health facility and neonate receive timely quality neonatal care. Even though in settings with well-functioning midwife programmes the provision of midwife-led continuity of care (MLCC) can reduce preterm births by up to 24%, in low and middle income countries is significantly challenging [10]. In Ethiopia, neonatal mortality declined more slowly than mortality among children aged 0–4 years. As a result, the share of neonatal deaths among all under-five deaths increased from 29% 1000 live births in 2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey (EDHS) to 30% 1000 live births in 2019 Ethiopian mini demographic health survey (EMDHS) [11, 12]. Lack of quality care at birth or skilled care and treatment immediately after birth and in the first days of life were the associated factors for neonatal morbidity and mortality. Preterm birth (prematurity), labor and delivery related complications (birth asphyxia, meconium stained amniotic fluid, hypothermia, hyperthermia, respiratory distress syndrome, or lack of breathing at birth), infections and birth defects were the commonest cause of neonatal deaths [7].

Improving the quality of maternal and newborn care from pregnancy to postnatal period, encouraging the quality of care given during the first week of neonatal life, and expanding quality services for small and sick newborns were the recommended strategy to prevent neonatal danger signs and its complications [4, 7]. In Ethiopia, there were several studies about women’s knowledge of neonatal danger signs and its associated factors. Most of the available studies are cross-sectional in design and conducted in limited areas which didn’t address all regions of the country; hence, we are unable to indicate more accurately women’s knowledge of neonatal danger signs at the national level. As a result, this systematic review would help policymakers and health managers and planners to make evidence-based decisions that have taken into account all the available information, as well as providing an indication as to the quality of the results. Therefore, this systematic review is designed to identify the level of women’s knowledge of neonate/newborn danger signs to present accurate information that could be used in policy formulation and practice evidence-based decision-making.

Methods

Study design and setting

Ethiopia is one of low-income countries located in Eastern Africa with a total fertility rate of 4.6. This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs and its associated factors in Ethiopia.

Search strategies

Studies were searched from online databases including MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Maternity and Infant Care and Wiley Online Library. Additionally, bibliographies of identified articles and grey literature, including Google scholar, MEDNAR, and World Wide Science were searched. Moreover, missing data were handled by contacting corresponding authors. Search terms were formulating using PICO guidelines through the online databases and comprehensive search strategy had been developed using different Boolean operators.

The following search terms were used: Knowledge OR Awareness OR Understanding AND “Neonatal danger signs” OR “newborn danger signs” OR “Warning signs of newborn” OR “Neonatal warning signs” OR “Unable to breastfeeding” OR “Convulsion” OR “Lethargy” OR “Difficulty in breathing” OR “Jaundice” OR “Hypothermia” OR “Hyperthermia” OR “Pus discharge” OR “Repeated Vomiting” AND “Mother’s” OR “Women” AND “Associated factors” AND Ethiopia and related terms. Systematic review with narrative synthesis was used to summarize the findings of articles in Ethiopia.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Population

Antenatal and postnatal women were included.

Study design

Observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, and retrospective and prospective cohort studies and national survey and surveillance reports) were included.

Study area

only studies conducted in Ethiopia without time limiting and reported the magnitude or at least one least adjusted associated factor of knowledge of neonatal danger signs among mother was included.

Publication status and language

Both published and unpublished reported articles in English language only were considered.

Searching date

Studies published till September 2/2019 were included.

Exclusion criteria

Citations without abstracts and/or full-text, commentaries, anonymous reports, letters, editorials and articles not reporting the outcome of the study were excluded after reviewing the full texts.

Outcome measurements

This systematic review and meta-analysis had two essential outcomes. These were:

Primary outcome

The level of knowledge of women’s towards neonatal danger signs.

Secondary outcome

Factors affecting knowledge of women’s towards neonatal danger signs which were measured by higher level of maternal educational status (yes/no), higher educational level of the husband (yes/no), access to mass media (yes/no), attending antenatal care visits (yes/no), attending postnatal care follow up (yes/no), place of delivery (health facility/home) were the main contributing factors for neonatal danger signs.

Data extraction

First, all studies obtained from all databases were exported to Endnote version X8 software to remove duplicates. Then after, all studies were exported to Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Two authors (AD and GG) independently extracted all the important data using a standardized data extraction form which was adapted from the JBI data extraction format. Substantial agreement between reviewers i.e. Cohen’s kappa coefficient > 0.60 was accepted and resolved through discussion and consensus. For the first outcome (prevalence) the data extraction format included (primary author, year of publication, regions, study area, sample size, and prevalence with 95%CI). For the second outcome (associated factors) data were extracted with 2 by 2 table format and then the log odds ratio for each factor was calculated.

Quality assessment

Two authors (AD&GG) independently assessed the quality of each studies using Newcastle-Ottawa-scale (NOS) for cross-sectional studies [13]. All Articles underwent systematic review and meta-analysis was cross-sectional studies. The methodological quality, comparability and the outcome and statistical analysis of the study were the three major assessment tools used to declare the quality of the study. Lastly, studies scored a scale of ≥7 out of 10 was considered as achieving high quality. During quality appraisal of the articles, any discrepancies between the two authors were resolved by taking the second group authors (AW, AG and BA). All of the studies were included based on the Newcastle –Ottawa Scale quality assessment criteria.

Data processing and analysis

Random effect model was applied to estimate the pooled prevalence of having good knowledge of neonatal danger signs among postnatal women. After extraction of the articles in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet format, the analysis was carried out using STATA version 11 statistical software. Cochrane Q-test and I2statistics were computed to assess heterogeneity among studies [14]. After computing the statistics, results showed there is significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 99.6%, p < 0.001). To estimate the overall prevalence of having good knowledge of the women, via back-transform of the weighted mean of the transformed proportions arcsine variance weights and Dersimonian-Laird weights for fixed-effects model and random effect model respectively [15]. Publication bias was assessed using egger’s test. Subgroup analysis was done based on study setting (facility vs community based), sample size and women’s spontaneous response to minimize the random variations between the point estimates of the primary study. Forest plot format was used to present the pooled point prevalence with 95%Cl. For associations, a log odds ratio was used to decide the association between associated factors and having good knowledge among mothers towards neonatal danger signs in the included studies.

Results

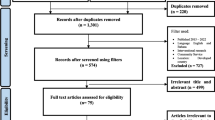

n the first step of our search, 566 articles were retrieved regarding the prevalence and associated factors of knowledge among postnatal women at MEDLINE/PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science and other sources described previously. Of 566 articles, 285 articles were excluded due to duplication. From the remaining 281 articles, 220 articles were excluded after review of their titles and abstracts due to as non-relevant to this review. Therefore, 61full-text articles were accessed and assessed for eligibility based on the pre-set criteria, which resulted in the further exclusion of 47articles primarily due to reason. As a result, 14 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of original studies

Among 14 articles which were published in Ethiopia until 2019, 6617 study participants were involved to determine the pooled prevalence of newborn danger signs among mothers. Regarding the study design, all the studies are cross-sectional. The sample size of the studies was ranged from 197 to 845. Three of the studies were from Amhara region [16,17,18], three from SNNPR [19,20,21], three from Oromia region [22,23,24], three from Tigray region [25,26,27], one from Addis Ababa [28], and one from Harar regional state [29] (Table 1).

Women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signsin Ethiopia

The overall pooled prevalence of mothers knowledge towards newborn danger signs was 40.7% (95%CI, 25.72, 55.67) (Fig. 2). High heterogeneity was observed across the included studies (I2 = 99.6, P < 0.001). As a result, a random-effects model was employed to estimate the pooled prevalence of knowledge of neonatal danger signs in Ethiopia.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

The existence of heterogeneity and publication bias was determined within the included studies, as a result, there was considerable heterogeneity across included studies in this meta-analysis (I2 = 99.6%). Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s tests, showing no statistically significant for estimating the prevalence of maternal knowledge towards newborn danger signs in Ethiopia (P = 0.562). There is symmetrical distribution of included studies in funnel plot which suggests there is no evidence of publication bias (Fig. 3).

Subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the study setting and sample size. Therefore after conducting the subgroup analysis of study setting, the pooled prevalence reported in facility based was 40.9% (95% CI: 13.16, 68.59) and community based with a prevalence of 40.6% (95%CI: 23.47, 57.64). Regarding sample size the prevalence of maternal knowledge towards neonatal danger sign was higher in studies with a sample size of > 400 having a prevalence of 42.8% (95%CI: 22.21, 63.28) than studies conducted with a sample size of ≤400 having a prevalence of 36.9% (95%CI, 22.13, 51.62).

Besides, subgroup analysis of women’s knowledge about neonatal danger signs was conducted based on the number of spontaneous responses given by women. Ten articles assessed women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs based on at least three spontaneous responses given by women [16, 18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26,27, 29] and the remaining four articles assessed based on at least one spontaneous responses, at least two spontaneous responses, at least four spontaneous responses and at least six spontaneous responses [17, 21, 23, 28].

Accordingly, the level of women’s knowledge about neonatal danger signs with seven individual study populations assessed with at least three spontaneous responses was found to range between 18.2 and 64.4%, with an overall summarized random effect meta-analysis knowledge of 41.9% [95% CI; (30.17, 53.6%), I2 = 98.8, p < 0.001]. Women’s knowledge about neonatal danger signs with four individual study populations assessed with at least one, two, four and six responses was found to range between 9.4 and 88.9% (Table 2).

Factors associated with women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs in Ethiopia

The association between the educational status of the mother and knowledge of mother towards neonatal danger signs in Ethiopia

Three cross-sectional studies were included to see the association between level of education and knowledge of mothers towards neonatal danger signs. The pooled odds ratio of higher maternal education level were 3.86 times more likely knowledgeable towards neonatal danger signs than their counterparts (AOR = 3.86; 95% CI; 2.3–6.5). These studies hadn’t indicated heterogeneity (I2 = 0, p = 0.934) with no evidence of publication bias using egger test with p-value of 0.076 (Fig. 4).

The association between the educational status of the husband and knowledge of mother towards neonatal danger signs in Ethiopia

In this meta-analysis, having a higher educational level is 4.57 times more likely to have good knowledge of the mother regarding the danger sign of the newborn. The heterogeneity was not detected in this included studies (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.81) without evidence of publication bias using egger test with p-value of 0.941 (Fig. 5).

Antenatal care follow-up is one of the associated factors for women to have good knowledge towards danger sign of the newborn

In this study women who had at least one antenatal care follow up were 2.7 times more likely to have good knowledge on danger sign of the newborn than women who hadn’t antenatal care follow up. Heterogeneity was not seen in these meta-analysis of included studies (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.886). Possibility of publication bias was seen using egger test with p-value of 0.296 (Fig. 6).

The association between postnatal care follow-up and knowledge of the mother on danger sign of the newborn in Ethiopia

From five cross-sectional studies having postnatal care follow-up was an associated factor for knowledge of the mother on danger sign of the newborn. Having postnatal care follow up were 2.55 more likely to have good knowledge of the mother towards danger sign of the newborn than mothers who hadn’t postnatal care follow-up (AOR = 2.55; 95%CI;1.72–3.79).. In this meta-analysis, the included studies were characterized by moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 69.4%; p = 0.003) resulting in the use of a random effect meta-analysis model. Publication bias was detected using Egger’s tests with p-values of 0.011(Fig. 7).

Accessing mass media is one of the associated factors for women to have good knowledge of danger sign of the newborn

In this study women who had can access mass media were 1.69 times more likely to have good knowledge of danger sign of the newborn than their counterparts. Minimal heterogeneity was detected in the included studies (I2 = 17.4%, p = 0.298). Possibility of publication bias was computed using egger test with p-value of 0.296 (Fig. 8).

Association between place of delivery and maternal knowledge on danger sign of newborn

Lastly, meta-analysis was done to see the association between place of delivery and knowledge of the mother on the danger sign of the newborn. Women who gave birth at health institution were 2.51 times more likely to have good knowledge of danger sign of the newborn. The included studies exhibited minimal heterogeneity (I2 = 9.9%, p = 0.329) as a result random effect model meta-analysis was used. Publication bias was detected using egger test with a p- value of 1.00 (Fig. 9).

Discussion

Inadequate knowledge of parents on neonatal danger signs during the neonatal period may perhaps escort to parents’ confusion and decreased quality of care which intimidates the neonatal health and could yet lead to neonatal morbidity and mortality. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of maternal knowledge towards neonatal danger signs and its associated factors in Ethiopia. In this review, the overall pooled prevalence rate of women’s knowledge on neonatal danger sign was 40.7% (95%CI = 25.72, 55.68. The finding of the study is higher than the study done in Malawi [30], Afghanistan [31] and Ghana [32]. This might be due to variation in time, measurement of newborn danger signs and socio-demographic characteristics of the study population.

The odds of having knowledge on neonatal danger sign were 3.86 times more likely among women having higher educational level than their counterparts. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Ghana [33], Bangladesh [34], Uganda [35] and Tanzania [36]. This might be justified by an increased chance of the mother’s exposure to postnatal counselling which would possibly increase knowledge of the mother regarding neonatal danger signs.

Having higher educational level of the husband/partner was 4.57 times more likely to understand the neonatal danger signs than their counterparts. This might be due to the fact that an educated husband might positively influence mothers’ knowledge on neonatal danger signs since the husband is the head of the housing member with high decision-making ability.

The odds of having knowledge on neonatal danger sign were 2.7times more likely among antenatal care attended women than those who have no antenatal care follow-up. This finding supported by the studies conducted in Ghana [33], Bangladesh [34]. This might be due to the fact that having ANC visits during pregnancy may have the high chance of getting counselling on maternal and newborn danger signs from healthcare professionals in charge of the service provided which ultimately improves their knowledge on newborn danger signs.

The odds of having knowledge on neonatal danger sign were 2.55 times more likely among postnatal care attended women than those who have no postnatal care follow-up. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Ghana [33] and Southern Ethiopia [37]. This might be due to the fact that mothers who attended postnatal follow-up have a high chance of getting information from health professionals regarding knowledge of newborn care.

Having access to mass-media was also found to be significantly associated with being knowledgeable with newborn danger signs. Women who had access to mass media were 1.69 times more likely knowledgeable on newborn danger signs as compared with their counterparts. This might be due to mothers who have access to mass media have a high possibility of gaining information regarding newborn danger signs which contribute to shaping one’s mind [38]. Moreover, giving birth at health institutions was found to be another determinant factor of mother’s knowledge about newborn dangers signs. Women who gave birth at health institutions were 2.51 times more likely to have good knowledge k on newborn danger signs as compared to women who gave birth at home. Women who had postnatal care follow up have been counselled about neonatal danger sign and its consequences; hence increasing the knowledge of the women about danger sign of the newborn, might understand the prevention and complications of neonatal problems. Therefore, they become active to recognize early about the type of danger signs of newborns which ultimately increases their knowledge on danger signs of the newborn.

Conclusion

In this study, maternal knowledge towards neonatal danger signs in Ethiopia was low. Higher educational status of the mother, higher educational status of the husband, access to mass media, having antenatal care follow-up, having postnatal care follow-up, and giving birth at health institutions were factors associated with knowledge of the mother towards danger sign of the newborn. Therefore, based on the study findings, authors recommended that encouraging mother’s to have antenatal care follow-up, postnatal care follow-up and promoting institutional delivery which ultimately increases the potential of mothers to acquire knowledge towards neonatal danger signs.

Limitation and strength of the study

As strength of the study, we used broader inclusion criteria to include studies conducted both at health facilities and in the community to incorporate a wider range of mother’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs.

In this study, all the included articles were a study conducted with a cross-sectional design. Therefore, this review shows the level of mother’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs only at a single point in time, and it is impossible to infer causal relationships among variables. There was no standardized method of measuring thelevel of mother’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs and hence researchers have used their measuring method. Therefore, the result of this analysis was presented for articles which assessed the level of mother’s knowledge using ‘at least one and above spontaneous responses’ and ‘above mean responses’ making it difficult to pool the level of knowledge together. Furthermore, sub group analysis was employed to see the level of women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs.

Availability of data and materials

All related data has been presented within the manuscript. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the authors on request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- AA:

-

Addis Ababa

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CSA:

-

Central Statistical Agency

- SNNPR:

-

Southern Nation Nationalities and Peoples Region

- UNICEF:

-

United Nation Children’s Emergency Fund

References

WHO U. WHO, W. B., UN department of economic and social affairs, UN children's fund 2017b. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2017. 2017. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/levels-trends-child-mortality-report-2017. Accessed 4 Dec 2017.

Del Barco R. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness. Tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health; 2004.

Noordam AC, Sharkey AB, Hinssen P, Dinant G, Cals JW. Association between caregivers’ knowledge and care seeking behaviour for children with symptoms of pneumonia in six sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):107.

Sibley LM, Tesfaye S, Fekadu Desta B, Hailemichael Frew A, Kebede A, Mohammed H, et al. Improving maternal and newborn health care delivery in rural Amhara and Oromiya regions of Ethiopia through the maternal and newborn health in Ethiopia partnership. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2014;59(s1):S6–S20.

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365(9462):891–900.

Rajaratnam JK, Marcus JR, Flaxman AD, Wang H, Levin-Rector A, Dwyer L, et al. Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards millennium development goal 4. Lancet. 2010;375(9730):1988–2008.

WHO. World Health Organization; Newborns: reducing mortality; 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality .

Hug L, Alexander M, You D, Alkema L. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e710–e20.

Lawn JE, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, Cousens S. 3.6 million neonatal deaths--what is progressing and what is not? Semin Perinatol. 2010;34(6):371–86.

Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2226–34.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa and Rockville: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. Rockville: EPHI and ICF. 2019.

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79.

Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39.

Desalegn Tesfa Asnakew MTE. Alemayehu Digssie Gebremariam,. Level of Knowledge About Neonatal Danger Signs and Associated Factors Among Mothers Who Delivered at Home in Fogera District, South West, Ethiopia. Biomed Stat Inform. 2018;3(4):53–60.

Jemberia MM, Berhe ET, Mirkena HB, Gishen DM, Tegegne AE, Reta MA. Low level of knowledge about neonatal danger signs and its associated factors among postnatal mothers attending at Woldia general hospital, Ethiopia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2018;4:5.

Nigatu SG, Worku AG, Dadi AF. Level of mother’s knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors in north west of Ethiopia: a community based study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:309.

Anmut W, Fekecha B, Demeke T. Mother’s knowledge and practice about neonatal danger signs and associated factors in Wolkite town, Gurage zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia, 2017. J Biomedical Sci. 2017;6(4):33.

Mersha A, Assefa N, Teji K, Bante A, Shibiru S. Mother’s level of knowledge on neonatal danger signs and its predictors in Chencha district, southern Ethiopia. Am J Nurs Sci. 2017;6(5):426–32.

Degefa N, Diriba K, Girma T, Kebede A, Senbeto A, Eshetu E, et al. Knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors among mothers attending immunization Clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:9180314.

Berhane M, Yimam H, Jibat N, Zewdu M. Parents’ Knowledge of Danger Signs and Health Seeking Behavior in Newborn and Young Infant Illness in Tiro Afeta District, Southwest Ethiopia: A Community-based Study. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2018;28(4):473–82.

Yadeta TA. Antenatal care utilization increase the odds of women knowledge on neonatal danger sign: a community-based study, eastern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):845.

Bulto GA, Fekene DB, Moti BE, Demissie GA, Daka KB. Knowledge of neonatal danger signs, care seeking practice and associated factors among postpartum mothers at public health facilities in ambo town, Central Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):549.

Adem N, Berhe KK, Tesfay Y. Awareness and Associated Factors towards Neonatal Danger Signs among Mothers Attending Public Health Institutions of Mekelle City, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015. J Child Adolesc Behav. 2017;05(06):365.

Misgna HG, Gebru HB, Birhanu MM. Knowledge, practice and associated factors of essential newborn care at home among mothers in Gulomekada District, eastern Tigray, Ethiopia, 2014. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):144.

Berhea TA, Belachew AB, Abreha GF. Knowledge and practice of essential newborn care among postnatal mothers in Mekelle City, North Ethiopia: a population-based survey. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202542.

Berhan D, Gulema H. Level of Knowledge and Associated Factors of Postnatal Mothers’ towards Essential Newborn Care Practices at Governmental Health Centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2018.

Tekulu F, Assefa D. Knowledge of neonatal danger signs and associated factors among mothers who gave birth the last four months attending immunization services in Harar town public health facilities, Ethiopia: Haramaya University; 2017.

Chirwa T, Bello G, Nkhoma P, Kaphuka J. Newborn health program knowledge practice and coverage survey for mothers of children 0-23 months in Mzimba District Malawi. Final report; 2007.

Ministry of Health. National Standards for Reproductive Health Service Newborn care services. Transitional Islamic Government of Afghani-Kabul stan,. :39. 2015.

Hill Z, Kendall C, Arthur P, Kirkwood B, Adjei E. Recognizing childhood illnesses and their traditional explanations: exploring options for care-seeking interventions in the context of the IMCI strategy in rural Ghana. Tropical Med Int Health. 2003;8(7):668–76.

Okawa S, Ansah EK, Nanishi K, Enuameh Y, Shibanuma A, Kikuchi K, et al. High incidence of neonatal danger signs and its implications for postnatal Care in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130712.

Zaman SB, Gupta RD, Al Kibria GM, Hossain N, Bulbul MMI, Hoque DME. Husband’s involvement with mother’s awareness and knowledge of newborn danger signs in facility-based childbirth settings: a cross-sectional study from rural Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):286.

Kabakyenga JK, Östergren P-O, Turyakira E, Pettersson KO. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness practices among women in rural Uganda. Reprod Health. 2011;8(1):33.

Pembe AB, Urassa DP, Carlstedt A, Lindmark G, Nyström L, Darj E. Rural Tanzanian women's awareness of danger signs of obstetric complications. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(1):12.

Abebo TA, Tesfaye DJ. Postnatal care utilization and associated factors among women of reproductive age Group in Halaba Kulito Town, Southern Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):9.

Asp G, Pettersson KO, Sandberg J, Kabakyenga J, Agardh A. Associations between mass media exposure and birth preparedness among women in southwestern Uganda: a community-based survey. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):22904.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD and GG developed the draft proposal under the supervision of AW, AG and BA. All authors (AD, GG) critically reviewed, provided substantive feedback and contributed to the intellectual content of this paper and made substantial contributions to the conception, conceptualization and manuscript preparation of this systematic review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Demis, A., Gedefaw, G., Wondmieneh, A. et al. Women’s knowledge towards neonatal danger signs and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 20, 217 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02098-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02098-6