Abstract

Background

In developed economies, obesity prevalence is high within children from some culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. This study aims to identify whether CALD groups in Victoria, Australia, are at increased risk of childhood overweight and obesity, and obesity-related dietary behaviours; compared to their non-CALD counterparts.

Methods

Objective anthropometric and self-report dietary behavioural data were collected from 2407 Grade 4 and 6 primary school children (aged 9–12 years). Children were categorised into CALD and non-CALD cultural groups according to the Australian Standard Classification of Languages. Overweight/obesity was defined according to the World Health Organization growth reference standards. Obesity-related dietary behaviour categories included excess consumption of takeaway foods, energy-dense, nutrient-poor snacks and sugar sweetened beverages. T-tests and chi-square tests were performed to identify differences in weight status and dietary behaviours between CALD and non-CALD children. Logistic regression analyses examined the relationship between CALD background, weight status and dietary behaviours.

Results

Middle-Eastern children had a higher overweight/obesity prevalence (53.0%) than non-CALD children (36.7%; p < 0.001). A higher proportion of Middle-Eastern children had excess consumption of takeaway foods (54.9%), energy-dense, nutrient-poor snacks (36.6%) and sugar sweetened beverages (35.4%) compared to non-CALD children (40.4, 27.0 and 25.0%, respectively; p < 0.05). Southeast Asian and African children were 1.58 (95% CI = [1.06, 2.35]) and 1.61 (95% CI = [1.17, 2.21]) times more likely, respectively, to consume takeaway foods at least once per week than non-CALD children.

Conclusions

Disparities in overweight/obesity prevalence and obesity-related dietary behaviours among children in Victoria suggest the need for cultural-specific, tailored prevention and intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Childhood overweight and obesity is highly prevalent [1] and associated with a number of immediate and long-term adverse health outcomes [2, 3]. In 2014–15, 27.4% of Australian children aged 5–17 years were classified as overweight (20.2%) or obese (7.4%) [4]. Demographic and socioeconomic disparities in the distribution of childhood overweight and obesity exist in developed economies such as Australia [5,6,7,8]. Several studies have found that the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity differs according to ethnic or cultural background, with minority groups often bearing a disproportionate burden [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) groups constitute a significant proportion of the Australian population. In 2016, 49% of the population were first (born outside of Australia) or second (Australian-born with at least one overseas-born parent) generation Australian, and 21% spoke a language other than English at home [18]. Previous research has identified that Australian children of Middle-Eastern [7, 9,10,11, 14], Asian [14], Pacific Islander [7, 9, 10] and European [9,10,11] backgrounds have an increased risk of overweight and obesity compared to children from English-speaking backgrounds (non-CALD). Most recently, data from the 2015 New South Wales (NSW) Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (SPANS) found that the prevalence of combined overweight and obesity among Middle-Eastern children (42.9%) was almost double that of non-CALD children (21.8%) [19]. While the sample was representative of children in NSW, the findings may not be generalisable to other regions of Australia due to variations in CALD populations across states [18]. Additionally, the categorisation of children into only four broad cultural backgrounds according to the Australian Standard Classification of Languages (Asian, European, Middle-Eastern and English-speaking) may mask variations in overweight and obesity prevalence within CALD subgroups. To develop a better understating of the cultural disparity in childhood overweight and obesity, additional research with disaggregated CALD groups is required.

Despite the known association between dietary behaviours and weight status [20], research on the dietary behaviours of CALD children is limited. Investigating obesity-related dietary behaviours (e.g. high consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor [EDNP] foods) [21] among CALD groups may identify practices contributing to their increased weight status which can be targeted. To our knowledge, SPANS is one of the few Australian studies to report on dietary behaviours of CALD children [19]. The 2015 SPANS found that compared to non-CALD children, the prevalence of consuming takeaway food at least once per week was significantly higher among Asian and Middle-Eastern children, while drinking more than one cup of soft drink per day was higher among Middle-Eastern children [19]. Although data on the consumption of several EDNP snack foods (e.g. fried potato products, confectionary) [21] were collected in SPANS, differences in these behaviours according to CALD background were not reported [22].

This study seeks to address gaps in the literature by examining self-report dietary and measured anthropometry data among primary school children to identify whether CALD groups in Victoria, Australia, are at increased risk of childhood overweight and obesity, and obesity-related dietary behaviours compared to their non-CALD counterparts.

Methods

Setting

This study utilised baseline (2014) data of children participating in Healthy Together Victoria and Childhood Obesity Study (HTVCO). HTVCO is a repeat cross-sectional study which aims to examine the effect of Healthy Together Victoria (HTV), a community-based lifestyle initiative of the State Government, on the prevalence of overweight and obesity and associated risk factors among school-aged children [23].

Participants and recruitment

Sampling technique

Random sampling was used to invite three primary schools within each of 26 Local Government Areas across Victoria, Australia which reflected the intervention and comparison HTV communities. Where all invited schools declined to participate, additional schools were invited in groups of three until at least one school per Local Government Area accepted. A total of 147 primary schools were invited to participate, of which 48 consented (school-level response rate 32.7%).

All students in Grade 4 (aged 9–10 years) and Grade 6 (aged 11–12 years) enrolled in participating schools were invited to take part in the study through the distribution of a plain language statement and opt-out consent form. Students were considered to have provided informed consent unless an opt-out form signed by parents or guardians was returned to the school or verbal consent was not confirmed by the student at the time of measurement. Data collection took place during Term 3 (July–September) of 2014. Of the 3235 students invited from consenting schools, 377 opted out of the study, and 301 were absent on the data of data collection; resulting in a total of 2557 participants (79% response rate).

Data collection

Data collection comprised objective measures of height and weight (3–5 min per participant) and a self-reported questionnaire administered via an electronic tablet (20–30 min to complete). All measurements were conducted during the school day by trained research staff.

Height and weight

Students’ measurements were taken behind portable screens while wearing a single layer of light clothing and shoes removed. Height was measured using a portable stadiometer (Charder HM-200P Portstad, Charder Electronic Co Ltd., Taichung City, Taiwan) to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight was measured using an electronic weight scale (A&D Precision Scale UC-321; A7D Medical, San Jose, CA) to the nearest 0.1 kg. All measurements were taken twice, and a third measurement taken if there was a discrepancy (0.5 cm height; 0.5 kg weight) between the first two measures. Mean height and weight measurements were used to generate Body Mass Index (BMI) z-scores according to the World Health Organization (WHO) international growth reference standards [24]. Overweight/obesity (> + 2SD) was defined according to the BMI z-score for age and sex using the WHO growth reference standards [24].

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics including age, gender and language spoken at home were collected through a self-reported questionnaire. Language spoken at home was used as a measure of cultural and linguistic diversity. Students were categorised into cultural groups according to the Australian Standard Classification of Languages (1. non-CALD [English-speaking], and 2. CALD [European, Middle-Eastern, Southern Asian, Southeast Asian, Eastern Asian and African]) [25]. Students with missing or ‘other’ language data (N = 150) were excluded from the analyses. School postcode was used as a proxy measure of socioeconomic status using the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Socioeconomic Index for Areas (SEIFA) Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage [26]. School postcode was also used to categorise students’ locality (i.e. major city, inner regional or outer regional) according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2011 Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Structure [27].

Dietary behaviours

Dietary behaviours were measured using the Simple Dietary Questionnaire (SDQ) [Parletta N, Frensham L, Peters J, O'Dea K, Itsiopoulos C: Validation of a simple dietary questionnaire with adolescents in an Australian population, unpublished]. Based on the former Australian Dietary Guidelines [28], items from the SDQ measure consumption of fruit, vegetables, takeaway foods, EDNP snack foods, sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) and sweetened or plain dairy foods. Participants indicated usual number of vegetable and fruit serves per day on a 15-point scale, with possible responses ranging from ‘none’ to ‘more than seven serves per day’ in half-serve increments. Frequency of consumption of takeaway foods was indicated on an 8-point scale, ranging from ‘rarely or never’ to ‘every meal’. Consumption of all other items were measured on an 8-point scale, ranging from ‘rarely or never’ to ‘3 times or more per day’. The SDQ has been validated among Australian school children aged 13 to 16 years and demonstrated moderate test-retest reliability and validity when assessed against a 24-h dietary recall. Vegetable consumption demonstrated test–retest reliability of r = 0.76 and validity of r = 0.42, while fruit consumption demonstrated test–retest of r = 0.73 and validity of r = 0.57.

Results from a subset of five questions on the SDQ (frequency of consumption of take-away food, EDNP snacks and SSBs) were used to analyse obesity-related dietary behaviours. Individual dietary behaviours were dichotomised as ‘obesity-related’ or ‘non-obesity related’ according to the Australian Dietary Guidelines [21] and previous studies. Obesity-related dietary behaviours included takeaway food ≥1/week (interpreted as excess takeaway consumption), EDNP snacks ≥2/day (interpreted as excess EDNP snacks) and SSBs ≥1/day (interpreted as excess SSBs). Other consumption frequencies were classified as non-obesity related.

Data analyses and power calculation

All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata v.14 statistics software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). For descriptive analyses, proportions or means and standard deviations were calculated. T-tests and chi-square tests were performed to identify differences in weight status and dietary behaviours between CALD subgroups and the non-CALD group. Logistic regression analyses were carried out to examine the relationship between CALD background and weight status and dietary behaviours. Two models were investigated: model 1: unadjusted results; model 2: adjusted for potential confounders including age, gender, socioeconomic status, geographical location and school clustering. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Sample size calculation

A sample of 327 participants in each group (CALD and non-CALD, total N = 654) was required to detect a 10% difference in overweight/obesity prevalence with 80% power and an alpha level of 0.05. These sample size calculations were based on data from the 2015 SPANS survey whereby a 21.1% difference in overweight/obesity prevalence between Middle-Eastern background and English-speaking primary school children was observed [19].

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 2407 participants, 50.2% were female, and the mean age was 11 years (SD = 1.1). More than half (54.4%) of children lived in major cities, and 56.7% lived in areas categorised as being in the lower two SEIFA quintiles. Just under a third (29.2%) of participants were classified as CALD: 7.9% European, 6.1% Middle-Eastern, 4.9% Southern Asian, 4.1% Southeast Asian, 3.4% African and 2.9% Eastern Asian backgrounds.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity

Over a third (37.3%) of all participants were classified as overweight or obese (Table 1). Except for Middle-Eastern children, no significant differences in overweight/obesity prevalence were observed between CALD subgroups and the non-CALD group. More than half (53%) of Middle-Eastern children were categorised as overweight/obese, compared to 38.5% of non-CALD children (p < 0.001).

Dietary behaviours

Across CALD subgroups, several variations in dietary behaviours were found (Table 1). African, Southeast Asian, Southern Asian and Middle-Eastern children had a significantly higher weekly consumption of takeaway foods compared to non-CALD children (p < 0.05). Frequent takeaway food consumption was highest among the Southeast Asian group, with 58.2% of children. Except the Middle-Eastern group, there were no significant differences in the proportion of children consuming two or more sugary or salty snacks per day among CALD subgroups compared to the non-CALD group. Snack consumption was almost 10% higher among Middle-Eastern compared to non-CALD children (36.6 and 27.0%, respectively; p = 0.14). SSB consumption frequency was significantly higher among Middle-Eastern (35.4%, p = 0.007) and African (36.6%, p = 0.019) groups compared to the non-CALD group (25.0%).

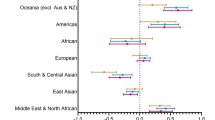

Model 1 (unadjusted) shows children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds as 1.94 times more likely than non-CALD children to be overweight or obese (CI = [1.36, 2.76]; p < 0.001) (Table 2). This association remained statistically significant after adjustment (OR = 1.99; 95% CI = [1.31, 3.04]; p = 0.001) (Model 2). No other significant associations in the odds of overweight and obesity among the other CALD sub-group compared to the non-CALD group were observed.

Associations with dietary behaviours differed across CALD subgroups. Apart from takeaway food and SSB consumption in the Middle-Eastern group, all other associations between CALD subgroups and dietary behaviours remained statistically significant after adjustment. In the adjusted model, children of Southeast Asian and African background were 1.58 (95% CI = [1.06, 2.35]; p = 0.024) and 1.61 (95% CI = [1.17, 2.21]; p = 0.003) times more likely, respectively, to consume takeaway one or more times per week than non-CALD children. Compared to the non-CALD group, children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds had 1.5 times the odds of consuming two or more EDNP snacks per day (95% CI = [1.05, 2.15]; p = 0.026). The odds of consuming one or more SSBs per day were significantly higher among children of African backgrounds (OR = 1.76; 95% CI = [1.30, 2.38]; p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study examined differences in weight status and dietary behaviours among CALD and non-CALD children in Victoria. Overall, rates of overweight and obesity were high among the sample, although children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds were found to have significantly higher odds of overweight/obesity compared to non-CALD children. Poorer dietary behaviours were observed in several CALD subgroups compared to the non-CALD group. A higher proportion of Middle-Eastern children were found to have excess takeaway food, EDNP snack and SSBs consumption compared to non-CALD children. The odds of excess takeaway consumption were significantly higher among Southeast Asian and African children compared to their non-CALD counterparts. African children also had a higher likelihood of excess SSB consumption. These findings collectively present intervention opportunities to improve poor dietary behaviours. For example increasing the promotion of, and access to healthy food options and increasing water consumption using culturally appropriate strategies.

Overweight and obesity prevalence

In the present study, over half (53%) of children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds were classified as overweight or obese, compared to 36.7% of non-CALD children. This finding is supported by previous Australian research, which has consistently identified high rates of overweight and obesity among Middle-Eastern background children over the past two decades [9, 29]. The proportion of overweight or obese Middle-Eastern background and non-CALD children in the present study is considerably higher than that reported in the 2015 SPANS (37.5 and 13.3%, respectively) [19]. This is likely due to methodological differences in SPANS, such as a opt-in recruitment resulting in a response rate of 67.9% and the use of International Obesity Taskforce cut-points to classify weight status, which typically has more conservative estimates of overweight and obesity than the WHO system [30, 31]. Nevertheless, findings from the present study add to the large body of evidence identifying a need to address the disproportionate prevalence of overweight and obesity among children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds.

Contrary to prior research, overweight and obesity prevalence among all other CALD subgroups did not differ significantly to that of non-CALD children. Australian children of African [9], European [9,10,11] and Pacific Islander [9, 10] backgrounds have previously been found to have an increased risk of excess weight. Due to the small sample sizes of CALD subgroups in the present study, there may not have been sufficient power to detect differences in weight status compared to the non-CALD group. Differences in identified at-risk groups between the present and previous studies may also be somewhat explained by alternate methods of classifying CALD background. For instance, Waters et al. [11] determined CALD background according to maternal region of birth. An additional 24% of children were classified as CALD using this method compared to language spoken at home, thus resulting in a higher potential of identifying overweight and obesity among those classified as CALD [11]. Additionally, children of Pacific Islander backgrounds were excluded from analysis in the present study due to insufficient numbers. As such, future research should endeavour to recruit a sample large enough to include and be representative of all CALD subgroups so that at-risk groups can be accurately identified.

Dietary behaviours

Excess takeaway consumption appeared to be a significant issue among several CALD subgroups in the present study. Excluding children of European and Eastern Asian backgrounds, more than half of children among all other CALD subgroups consumed takeaway one or more times per week. This is concerning, as takeaway foods are typically high in energy, saturated fat, salt and sugar, and have been associated with excess weight in children [32,33,34]. Furthermore, higher consumption of takeaway foods has been shown to not only be associated with an increased risk of obesity; but also other metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes; along with cardiovascular disorders [35]. There are many aspects that may influence takeaway consumption, including its relative affordability, accessibility, convenience and media advertising [36, 37]. However, the persisting relationship between takeaway consumption and Southeast Asian or African background in the adjusted regression model is indicative of an independent cultural influence. For example, high cultural regard for Western foods and dietary acculturation have been identified as factors influencing takeaway consumption among African migrants in Australia [38, 39].

Overall, the proportion of children consuming one or more SSBs per day within CALD subgroups was similar to that of non-CALD group in the present study. However, a significantly higher prevalence of SSB consumption was identified among Middle-Eastern and African background children. Furthermore, compared to non-CALD children, African children had almost two times the odds of excess SSB consumption. Similar results among children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds were reported in SPANS, who were found to have a significantly higher prevalence of soft drink consumption and availability of soft drinks in the home compared with non-CALD children [19]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate SSB consumption among children of African backgrounds in Australia. Considering the association between SSB consumption and increased weight status [40], this behaviour among children of African backgrounds warrants further investigation. Additionally, this finding highlights the importance of investigating obesity-related dietary behaviours among minority CALD subgroups.

Children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds were also found to have a significantly higher prevalence of consuming two or more sugary or salty snacks per day compared to non-CALD children. This finding is consistent with previous research [14, 19, 41]. In an analysis of the cumulative intake of ‘junk’ foods (e.g. sweet or savoury biscuits, ice-cream) among children in NSW, Boylan et al. [41] found that over half of children from Middle-Eastern backgrounds were high junk food consumers. It has also been shown that children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds are often rewarded for good behaviour with sweets [14, 19], which may partially explain the higher odds of excess snack consumption compared to non-CALD children in the present study.

Strengths and limitations

Data for this study were drawn from a large sample of Victorian primary school children spanning broad demographic and geographic areas. At a school-level, non-response bias was minimised due to the opt-out recruitment process. Therefore, the present study may have more accurately estimated overweight/obesity prevalence compared to research with opt-in procedure [42]. A further strength is the use of standardised protocols for the collection of height and weight measurements.

There are also some limitations of this research to consider. Firstly, as these data are cross-sectional, causality cannot be inferred. In addition, BMI is not able to distinguish between fat and fat-free mass and therefore has limitations as a measure of overweight and obesity at an individual level. However, at a population-level, BMI is an accurate, cost and time efficient measure for population surveillance of childhood overweight and obesity and has very high specificity [43]. Dietary behaviours were self-reported by children and were therefore subject to recall and measurement bias. Food frequency questionnaires are commonly completed by parent proxy in children less than 12 years old due to cognitive development among young children potentially influencing food recall and estimated portion sizes [44]. However, parents of children may not be aware of foods consumed out of the home, and there is research to suggest that children as young as 8 years old are more accurate reporters of food frequency consumption than their parents [45]. The classification of CALD background according to language spoken at home is a potential limitation of this study, as it is possible that some CALD children speak predominantly English at home. Finally, while the sample was large, there was not sufficient power among all CALD subgroups to detect differences in weight status or dietary behaviours compared to non-CALD children. Future research examining differences in CALD groups speaking predominantly English compared to those speaking predominantly their native language would shed light on whether disparities between groups are influenced by lifestyle, genetic or a combination of factors. Examining the effects of acculturation on behaviours that influence weight status in migrant children living in Australia would also be beneficial [14]. In depth qualitative research to understand dietary choices in these CALD groups is also required.

Conclusion

This study identified a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds and revealed disparities in dietary behaviours among CALD compared to non-CALD children. These modifiable dietary behaviours present as areas for targeted and culturally appropriate childhood overweight and obesity intervention and prevention strategies, particularly among children of Middle-Eastern backgrounds. Additional research is required to understand the underlying causes that uniquely contribute to obesity-related dietary behaviours among CALD children.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CALD:

-

Culturally and linguistically diverse

- EDNDP:

-

Energy-dense, nutrient-poor

- HTV:

-

Healthy Together Victoria

- HTVCO:

-

Healthy Together Victoria and Childhood Obesity Study

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- SDQ:

-

Simple Dietary Questionnaire

- SEIFA:

-

Socioeconomic Index for Areas

- SPANS:

-

Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey

- SSB:

-

Sugar sweetened beverage

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Sanders RH, Han A, Baker JS, Cobley S. Childhood obesity and its physical and psychological co-morbidities: a systematic review of Australian children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;6:715.

Han JC, Lawlor DA, Kimm SYS. Childhood obesity. Lancet. 2010;375:1737–48.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: first results, 2014–15. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2014-15~Main%20Features~Children’s%20risk%20factors~31. Accessed 4 Apr 2018.

Barriuso L, Miqueleiz E, Albaladejo R, Villanueva R, Santos JM, Regidor E. Socioeconomic position and childhood-adolescent weight status in rich countries: a systematic review, 1990–2013. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:129.

Chung A, Backholer K, Wong E, Palermo C, Keating C, Peeters A. Trends in child and adolescent obesity prevalence in economically advanced countries according to socioeconomic position: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2016;17:276.

O'Dea JA. Gender, ethnicity, culture and social class influences on childhood obesity among Australian schoolchildren: implications for treatment, prevention and community education. Health Soc Care Comm. 2008;16:282–90.

Wang Y. Disparities in pediatric obesity in the United States. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:23–31.

O'Dea JA, Dibley MJ. Prevalence of obesity, overweight and thinness in Australian children and adolescents by socioeconomic status and ethnic/cultural group in 2006 and 2012. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:819–28.

Achat HM, Stubbs JM. Socio-economic and ethnic differences in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among school children. J Paediatr Child H. 2014;50:E77–84.

Waters E, Ashbolt R, Gibbs L, Booth M, Magarey A, Gold L, et al. Double disadvantage: the influence of ethnicity over socioeconomic position on childhood overweight and obesity: findings from an inner urban population of primary school children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008;3:196–204.

Zilanawala A, Davis-Kean P, Nazroo J, Sacker A, Simonton S, Kelly Y. Race/ethnic disparities in early childhood BMI, obesity and overweight in the United Kingdom and United States. Int J Obes. 2015;39:520–9.

El-Sayed AM, Scarborough P, Galea S. Ethnic inequalities in obesity among children and adults in the UK: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011;12:E516–34.

Hardy LL, King L, Hector D, Baur LA. Socio-cultural differences in Australian primary school children's weight and weight-related behaviours. J Paediatr Child H. 2013;49:641–8.

Labree W, van de Mheen D, Rutten F, Rodenburg G, Koopmans G, Foets M. Differences in overweight and obesity among children from migrant and native origin: the role of physical activity, dietary intake, and sleep duration. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–12.

Brug J, van Stralen MM, Te Velde SJ, Chinapaw MJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lien N, et al. Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: the energy-project. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34742.

Arcan C, Larson N, Bauer K, Berge J, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Dietary and weight-related behaviors and body mass index among Hispanic, Hmong, Somali, and white adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:375–83.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: Reflecting Australia - stories from the Census, 2016. 2017. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Cultural%20Diversity%20Data%20Summary~15. Accessed 10 Sep 2018.

Hardy LL, Mihrshahi S, Drayton BA, Bauman AE. NSW schools physical activity and nutrition survey (SPANS). Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2017.

Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;5(Suppl 1):4–104.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. 2013. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr 2018.

Krebs NF, Himes JH, Jacobson D, Nicklas TA, Guilday P, Styne D. Assessment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S193–228.

Strugnell C, Millar L, Churchill A, Jacka F, Bell C, Malakellis M, et al. Healthy together Victoria and childhood obesity - a methodology for measuring changes in childhood obesity in response to a community-based, whole of system cluster randomized control trial. Arch Public Health. 2016;74:16.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–7.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian standard classification of languages (ASCL), 2016. 2016. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1267.0. Accessed 4 Apr 2018.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: Socioeconomic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. 2018. www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2033.0.55.001/. Accessed 13 Apr 2018.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian statistical geography standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - remoteness structure, July 2016. 2018. www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1270.0.55.005July%202011?OpenDocument. Accessed 8 Apr 2018.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. 2013. https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/clinical-practice-guidelines-management-overweight-and-obesity. Accessed 11 Apr 2018.

Hardy LL, Mihrshahi S, Ding D, Jin K. Trends in overweight, obesity, and waist-to-height ratio among Australian children from linguistically diverse backgrounds, 1997 to 2015. IJO. 2019;43:116–24.

Scott J. Childhood obesity estimates based on WHO and IOTF reference values. J Obes Weight Loss Ther. 2015;5:1.

Wang Y, Wang JQ. A comparison of international references for the assessment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity in different populations. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:973–82.

Fraser LK, Clarke GP, Cade JE, Edwards KL. Fast food and obesity: a spatial analysis in a large United Kingdom population of children aged 13–15. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:e77–85.

Braithwaite I, Stewart AW, Hancox RJ, Beasley R, Murphy R, Mitchell EA. Fast-food consumption and body mass index in children and adolescents: An international cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:12.

Wellard L, Glasson C, Chapman K. Fries or a fruit bag? Investigating the nutritional composition of fast food children’s meals. Appetite. 2012;58:105–10.

Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Fast food pattern and cardiometabolic disorders: a review of current studies. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5(4):231–400.

Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9:221–33.

Janssen HG, Davies IG, Richardson LD, Stevenson L. Determinants of takeaway and fast food consumption: a narrative review. Nutr Res Rev. 2017;31:16–34.

Renzaho AMN. Fat, rich and beautiful: changing socio-cultural paradigms associated with obesity risk, nutritional status and refugee children from sub-Saharan Africa. Health Place. 2004;10:105.

Renzaho AMN, Burns C. Post-migration food habits of sub-Saharan African migrants in Victoria: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Diet. 2006;63:91–102.

Bucher Della Torre S, Keller A, Laure Depeyre J, Kruseman M. Sugar-sweetened beverages and obesity risk in children and adolescents: A systematic analysis on how methodological quality may influence conclusions. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:638–59.

Boylan S, Hardy L, Drayton B, Grunseit A, Mihrshahi S. Assessing junk food consumption among Australian children: trends and associated characteristics from a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:299.

Strugnell C, Orellana L, Hayward J, Millar L, Swinburn B, Allender S. Active (opt-in) consent underestimates mean BMI-z and the prevalence of overweight and obesity compared to passive (opt-out) consent. Evidence from the healthy together Victoria and childhood obesity study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:747.

Reilly JJ. Diagnostic accuracy of the BMI for age in paediatrics. IJO. 2006;30(4):595–7.

Livingstone MBE, Robson PJ, Wallace JMW. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Brit J Nutr. 2007;92:S213–22.

Burrows TL, Truby H, Morgan PJ, Callister R, Davies PSW, Collins CE. A comparison and validation of child versus parent reporting of children's energy intake using food frequency questionnaires versus food records: Who's an accurate reporter? Clin Nutr. 2013;32:613–8.

Acknowledgements

The following agencies (in alphabetical order) Colac Area Health, Colac Corangamite Network of Schools, Deakin University, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, Glenelg Shire Council, Portland District Health, Portland Hamilton Network of Schools, Southern Grampians Glenelg Primary Care Partnership, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool and District Network of Schools, Western Alliance, Western District Health Services have supported this project. In addition we would like to acknowledge the support from the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, in particular Denise Laughlin, Senior Policy Manager and Atika Farooqui, Senior Epidemiologist and the Victorian Department of Education and Training.

Disclaimer: “The opinion and analysis in this article are those of the author(s) and are not those of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Victorian Government, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Victorian Minister for Health”.

Funding

SA was supported to conduct this study by funding from an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council/ Australian National Heart Foundation Career Development Fellowship (APP1045836). SA is supported by US National Institutes of Health grant titled Systems Science to Guide Whole-of-Community Childhood Obesity Interventions (1R01HL115485-01A1). This study was supported by a NHMRC Partnership Project (APP1114118), a 2013 Australian National Heart Foundation Vanguard Grant (100259) and a 2015 Western Alliance Grants-In-Aid Award. The funding bodies were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SA developed the overall research program. BS, CS, KAB and JM conceptualised the study and the initial hypothesis. BS conducted analysis and interpretation and prepared the manuscript. All authors provided intellectual input, contributed to the development of the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for HTVCO was granted by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2013_095), the Victorian Department of Education and Training (2013_002013) and the Catholic Education Offices, Archdiocese of Melbourne, Sandhurst, Ballarat and Sale. Students enrolled in participating schools were invited to take part in the study through the distribution of a plain language statement and opt-out consent form. Students were considered to have provided informed consent unless an opt-out form signed by parents or guardians was returned to the school or verbal consent was not confirmed by the student at the time of measurement.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Descriptive statistics of Victorian primary school children by CALD background.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, B., Bolton, K.A., Strugnell, C. et al. Weight status and obesity-related dietary behaviours among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) children in Victoria, Australia. BMC Pediatr 19, 511 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1845-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1845-4