Abstract

Background

Childhood stunting is the most widely prevalent among under-five children in Ethiopia. Despite the individual-level factors of childhood stunting are well documented, community-level factors have not been given much attention in the country. This study aimed to identify individual- and community-level factors associated with stunting among under-five children in Ethiopia.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey was used. A total of 8855 under-five children and 640 community clusters were included in the current analysis. A multilevel logistic regression model was used at 5% level of significance to determine the individual- and community-level factors associated with childhood stunting.

Results

The prevalence of stunting was found to be 38.39% in Ethiopian under-five children. The study showed that the percentage change in variance of the full model accounted for about 53.6% in odds of childhood stunting across the communities. At individual-level, ages of the child above 12 months, male gender, small size of the child at birth, children from poor households, low maternal education, and being multiple birth had significantly increased the odds of childhood stunting. At community-level, children from communities of Amhara, Tigray, and Benishangul more suffer from childhood stunting as compared to Addis Ababa’s community children. Similarly, children from Muslim, Orthodox and other traditional religion followers had higher log odds of stunting relative to children of the protestant community.

Conclusions

This study showed individual- and community-level factors determined childhood stunting in Ethiopian children. Promotion of girl education, improving the economic status of households, improving maternal nutrition, improving age-specific child feeding practices, nutritional care of low birth weight babies, promotion of context-specific child feeding practices and narrowing rural-urban disparities are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A child with a height-for-age Z score (HAZ) less than minus two standard deviations below the median of a reference height-for-age standard is referred as stunted [1]. It reflects a process of failure to achieve the linear growth potential as a result of prolonged or repeated episodes of under-nutrition starting before birth [1]. It is further indicated as the irreversible outcome of inadequate nutrition and a major cause for morbidity during the first 1000 days of a child’s life [2]; which is considered as a better overall predictor of under-nutrition in children. Stunting affects large numbers of children globally and has severe short-and long-term health consequences including poor cognition and educational performance, low adult wages, lost productivity and increased risk of nutrition-related chronic diseases when accompanied by excessive weight gain later in childhood [3]. It is also a vicious circle; because women who were themselves stunted in childhood tend to have stunted offspring, creating an intergenerational cycle of poverty and reduced human capital that is difficult to break [4].

In Ethiopia, stunting is one the foremost necessary health and welfare issues among under-five children [5]. No matter the economic process and therefore the substantial decline of impoverishment within the past decades within the country, childhood stunting remains at a high level and continues to be a serious public health problem within the country [6]. The prevalence of stunting in 2000, 2005, 2011 and 2016 in under-five Ethiopian children was reported to be 58, 51, 44, and 38.4%, respectively [7]. It was estimated that average schooling achievement for a person who was stunted as a child in Ethiopia is 1.07 years lower than for a person who was never undernourished. Under-nutrition is implicated in 28% of all child mortality in Ethiopia. Child mortality associated with under-nutrition has reduced Ethiopia’s workforce by 8% [8].

According to several studies; factors such as sex [9,10,11], maternal education [11, 12], father education [13], maternal occupation [14, 15], household income [11, 16], antenatal care service utilization [14, 16, 17] source of water [18], colostrum feeding [19] and methods of feeding [15, 19] contribute to stunting in Ethiopia. However, most of the studies so far focus on individual-level factors affecting stunting rather than community-level factors. Studies that focus only on individual fixed effects factors could ignore group membership and focus exclusively on inter-individual variations and on individual-level attributes. In this case, it has the drawback of disregarding the potential importance of group-level attributes in influencing individual-level outcomes. In addition, if outcomes for individuals within groups are correlated, the assumption of independence of observations is violated, resulting in incorrect standard errors and inefficient estimates [20]. However, multilevel study design allows the simultaneous examination of the effects of group-level and individual-level predictors [21]. Thus, this study was designed to identify both the individual- and community-level factors that contribute to stunting in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data sources

A cross-sectional data were obtained from 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS). The EDHS data had been collected by the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency (ECSA) from January 18, 2016, to June 27, 2016 [22].

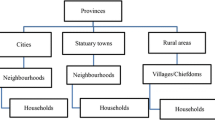

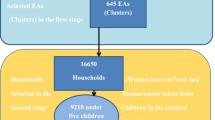

Sampling procedures

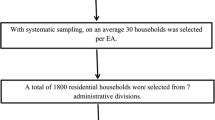

A proportional sample of 15,683 households from 645 clusters was enclosed within the data assortment. The samples were stratified, clustered and designated in two stages. Within the 1st stage, 645 clusters (202 urban and 443 rural) were designated from the list of enumeration areas supported the 2007 Population and Housing Census sample frame; and within the second stage, 28 households per cluster were designated. Overall, 18,008 households were selected; of that 17,067 were occupied. Of the occupied households, 16,650 were with success interviewed, yielding a response rate of 98%. within the interviewed households, 16,583 eligible ladies were known for individual interviews; and interviews were completed with the eligible ladies, yielding a response rate of 95%. For this study, a total of 10, 641 children less than 59 months were identified in the households of selected clusters. Among whom, the complete height-for-age record was collected from 8855 children and 640 clusters. The remaining 1786 children and 5 clusters had missing values on height-for-age records. Thus, the analysis of this study was based on the 8855 under-five children.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was stunting, standing among children below 5 years as outlined by height-for-age < − 2 z scores relative to World Health Organization standards [23]. Stunting of the ith child was measured as a dichotomous variable:

Yi = represent the stunting status of the ith child.

Independent variables

The independent variables for this study were elite supported previous studies conducted on the factors influencing childhood stunting at the worldwide and also the country level that were reviewed from the literature as determinants of stunting [14, 24, 25]. The variables were classified into two levels; individual- and community-level factors.

Individual-level factors

Age of child, sex of the child, mother’s body mass index, age of the mother, maternal education, father’s education, wealth index, mother’s marital status, mother’s perceived size of the child at birth, child had diarrhea, child had fever in the last weeks, place of delivery, number of under-five children in the household, antenatal care visits, mother’s age at 1st birth, mother’s occupation, father’s occupation, birth type, preceding birth interval and mass-media exposure. Since the study was conducted among under-five children and the majority of the data indicated that child breastfeeding was until the children reach 2 years old, leading to the presence of high missing value, child breastfeeding status was not included. Statistical analysis is likely to be biased when more than 10% of data are missing [26].

Community-level factors

Religion, region, place of residence, the source of drinking water, sanitation facilities, type of toilet, community women institutional delivery, community women education, and community women poverty were identified as community-level variables.

Data analysis procedures

For the hierarchical structure of the EDHS data, multilevel multivariable logistic regression analysis was used. Once weight every variable, descriptive statistics were reported with frequency and proportion. The degree of crude association for individual and community characteristics was checked by employing a χ2 test. The fixed effects of individual determinant factors and community distinction on the prevalence of stunting were measured using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR). Within the multilevel multivariable logistical regression analysis, four models were fitted for the result variable. The primary model (empty or null model) was fitted without explanatory variables. The second model (individual model), third model (community model) and fourth model (final model) variables were fitted for individual-level, community-level, and for each individual- and community-level variable respectively. The ultimate model was used to check for the independent effect of the individual- and community discourse variables on childhood stunting. The data were analyzed using the STATA statistical software system package version 14.0 (StataCorp., college Station, TX, USA). It was considered statistically significant if the P-values less than 0.05 with the 95% confidence intervals.

The goodness of fit test

Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were used as regression diagnostics to determine the goodness of fit of the model; since stepwise methods were used to compare models containing different combinations of predictors. According to Boco [27], the AIC is calculated as − 2 (log-likelihood of the fitted model) +2p, where p is the degree of freedom in the model; and BIC assesses the overall fit of a model and allows the comparison of both nested and non-nested models which is calculated as − 2 (log-likelihood of the fitted model) + ln (N)*P. After the values for each model of AIC and BIC were compared, the lowest one thought-about to be a better explanatory model [28].

Multicollinearity amongst the individual- and community-level variables was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The mean value of VIF < 10 was cut off point [29].

Results

Bivariate analysis of the effects of multilevel factors on childhood stunting

The prevalence of childhood stunting was 38.39%; of that 34.81% was for females and 37.93% for males (Table 1). Throughout the bivariate logistic regression analysis, individual characteristics such as live births between births, preceding birth interval, number of under-five children in the household, fever and diarrhea conditions of the child, marital status of women, and maternal occupation were not significantly associated with childhood stunting at p < 0.05 (Table 1). However, all the community characteristics were found to be significantly associated with childhood stunting (p < =0.05) except for the comminity women education level and type of toilet (Table 1). Children of women living in communities with comparatively lower level of institutional delivery had relatively higher (39.57%) proportion of childhood stunting than those with higher institutional delivery (31.05%).

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis of individual-level factors

During multivariable multilevel analyses, factors such as age and sex of the child, maternal education, wealth index, birth type, size of the child at birth, and maternal body mass index were found to be independently associated with the odds of childhood stunting (Table 2). The log odds of stunting was higher among children in the age group of 12–23 months and 24–59 months (AOR = 5.04, 95%CI: 3.95–6.41) and (AOR = 10.00, 95%CI: 7.71–12.98) respectively as compared to the age group of 0–5 months age. Moreover, female children were less likely to be stunted (AOR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.75–.94) as compared to males. Similarly, the odds of stunted children of single births were 47% (AOR = 0.53, 95%CI: 0.32–0.89) less likely than those multiple births. The large size children at birth were less likely than the odds of childhood stunting among children with small size (AOR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.40–2.00) and medium size (AOR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.02–1.40), after controlling for other individual- and community-level variables in the model (Table 2). Similarly, mothers with secondary and above education were 27% (AOR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.57–0.95) less likely to have stunted children compared to those with no education. The odds of childhood stunting were also higher among children from underweight mothers compared to those from overweight mothers (AOR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.17–2.08). Children from the rich households were 34% (AOR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.54–0.79) less likely to be stunted compared to children from poor households.

In contrast to the above, variables such as age of mother, age of mother at first birth, place of delivery, number of antenatal care (ANC) visits, father’s education level, mass media exposure and birth order of the last birth had no significance effect on childhood stunting (P ≤ 0.05) after adjusting for alternative individual- and community-level variables within the model (Table 1).

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis of community-level factors

During the multivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis, the community-level related factors such as religion, region, and place of residence were independently associated with log odds of childhood stunting among under-five children (P ≤ 0.05).

The likelihood of childhood stunting were 88% (AOR = 1.88, 95%CI: 1.16–3.07), 76% (AOR = 1.76, 95%CI: 1.01–2.92), and 75% (AOR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.10–2.76) higher from the regions of Amhara, Tigray, and Benishangul respectively compared to those from Addis Ababa.

Relative to children from Protestant families, those from Catholic families were 41% (AOR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.01–1.97) more likely to be stunted. By the same token, those from Muslim families were 33% (AOR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.08–1.64) more likely to be stunted; and children from the rural communities were also 29% (AOR: 1.29, 95%CI: 1.06–1.58) more likely stunted compared to children from the urban communities, after controlling other variables of individual- and community-level within the model (Table 2).

Results of the multilevel logistic regression model

In the empty model (Model-1), it had no individual- and community-level variables and it examined only the random and intercept variable. In the course of the analysis, there was significant variation in the log odds of childhood stunting across the communities (σ2u0 = 0.37, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 0.28–0.47). This variation remained significant after controlling the individual- and community-level factors in all models (Table 2). In Model-2 (individual model), it was also found significant variation in log odds of being stunted across the communities (σ2u0 = 0.21, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 0.13–0.33). According to the intra-community correlation coefficient implied, only 6% of the variance in the childhood stunting could be attributed to clustering effects (unexplained variation). In the log odds of being stunted across communities, 44% of the variance was explained by individual-level factors.

Model-3 (community model) examined the community-level factors of interest. There was significant difference in the log odds of being stunted across the communities (σ2u0 = 0.19, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 0.13–0.26); and the intra-community correlation coefficient implied by the estimated component variance was only 5.40% of the variance in childhood stunting that could be attributed to clustering effects. In the log odds of being stunted in the communities, 49.80% of the variance was explained by community-level factors.

Model-4 examined the individual- and community-level factors of interest. There was significant difference in the log odds of being stunted in the communities (σ2u0 = 0.17, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 0.10–0.29). In the log odds of being stunted variance across communities, 53.6% of the variance was explained by individual- and community-level factors combined.

Model fit statistics

The AIC and BIC values of Model-1, Model-2, Model-3 and Model-4 were found to be 11,420.09, 6373.387, 11,050.830, 6234.555, and 11,434.27, 6578.387, 11,199.350, 6551.946 respectively (Table 2). Lower values indicate the goodness of fit of the multilevel model. The smallest values of Log-likelihood, AIC, and BIC were observed in model 4 and this implies that model-4 for childhood stunting was a better explanatory model. This also suggests that the addition of the community compositional factors increased the ability of the multilevel model in explaining the variation in childhood stunting between the communities.

Multi-collinearity

Multi-collinearity amongst the individual- and community-level candidate explanatory variables was tested using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). In the current study, the mean VIF value was estimated to be 1.55 showing the absence of multi-collinearity in the models.

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of stunting was found to be 38.39% in Ethiopian under-five children. At the individual-level factors such as size of the child at birth, wealth index, education of the mother, birth type, BMI, sex and age of the child were found significant factors. Similarly, community-level factors such as religion, place of residence and region were found significant factors. The study indicated that the proportion change in variance of the full model was responsible for about 53.6% in the log odds of childhood stunting in the communities. The outcomes of median odds ratio, a measure of unexplained cluster heterogeneity, is 1.78, 1.54, 1.51, and 1.47 in models 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. Hence the results of median odds ratio revealed that there is unexplained variation between the clusters of the community. The ICCs results were also found to be above 2% of the total variance of childhood stunting in all models (Table 2). An ICC equal or greater than 2% is an indicative of significant group-level variance which is a minimum precondition for a multilevel study design [30].

In the present study, the childhood stunting was found to be significantly associated with the age of the child; as the child’s age increases the risk of being childhood stunted increases. Similar studies were reported in Bangladesh, Madagascar and Malawi [31,32,33]. It could be due to the inappropriate and late introduction of low nutritional quality supplementary food [34], and a large portion of guardians in rural areas are ignoring to meet their children’s optimal food requirements as the age of the child increases [35]. In addition, the lower odds of a breastfeeding rate of 0–11 month may indicate that exclusive and continuous breastfeeding has protective impacts for up to 1 year as defined by the WHO [36].

Small birth size children are usually born from low socioeconomic status and poor health [37, 38]. In the current study also confirmed that birth size and type of birth were found statistically significant. By the same token, study results confirmed that the probability of multiple births would be shrunk and low weight in similar to other studies [39, 40]. Multiple births involve birth defects like premature birth, birth weight, cerebral paralysis, all of which can inhibit child growth [41].

In the current study, male children were more likely to be stunted compared to their female groups of a comparable socioeconomic background similar to previous studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, Ethiopia and India [9,10,11, 39, 42, 43]. Gender difference in childhood stunting was more likely to be found in environments wherever there is stresses like continual infections and exposure to toxins and air pollutants [44]. On the contrary, another study from India showed that female children were more likely to suffer from childhood stunting than boys [45]. This might be due to the reason that breastfeeding duration was the lowest for daughters as their parents were trying for a son [46].

The childhood stunting was found to be inversely related to the mother’s level of education. This is in line with previous finding from developing countries [47]. These findings demonstrate the importance of the education of girls as alternative strategy to beat the burden of childhood stunting and to push sensible feeding practices for young children. Higher levels of maternal education can also reduce childhood stunting through other ways, such as increased knowledge of sanitation practices and healthy behaviors [48]. Children from rich mothers in wealth index were also positively associated with reducing childhood stunting. Studies conducted in Bolivia and Kenya found that less stunted children born to women with a high level of education and to women from high wealth households [49, 50].

In this study, low maternal BMI was found to be negatively associated with childhood stunting. This is also supported by the study conducted in Colombian school children [51] and in Southern Ethiopia [52]. A study from Brazil also suggested that maternal nutritional status was associated with child nutritional status [53]. According to Akombi et al. [24], the prenatal causes of child sub-optimal growth are closely related to maternal under nutrition, and are evident through low maternal BMI which predisposes the fetus to poor growth leading to intrauterine growth retardation; this in turn, is strongly associated with small birth size and low birth weight.

This study revealed that childhood stunting cannot be entirely explained by individual-level factors. The study suggested that children from Muslim, Catholic, and other traditional religion background were more likely to be stunted compared to children from communities with protestant families in line with previous studies in Ghana, Ethiopia, and India [54,55,56]. This may be due to some cultural factors, which are represented by the major religions in these countries [57].

The present findings suggested that children from Amhara, Benishangul, and Tigray communities were more stunted compared to children from Addis Ababa which is similar to previous studies that compared regional variations in nutritional status [58, 59]. This difference may be from the differential nutritional intake, the difference in the environment, socio-economic, and cultural differences [19].

Our study showed that children whose parents reside in rural areas had higher odds of childhood stunting than the urban areas. Possible explanations may be due to better-equipped urban health-care systems and higher access to health-care facilities. Urban populations usually have a higher educational level, economic status, and employment opportunities. [60]. This finding is similar with results from a cross-sectional study carried out in Mozambique, and Iran [61, 62]. On the other hand, in several countries, the rate of stunting in children living in slums is higher than in the rest of urban areas or rural areas [63].

Limitations

Since the data was cross-sectional type, it could not show causal inferences in relation to individual- and community-level factors with childhood stunting. Another limitation is the use of secondary data which has restricted ability to include other variables such as healthcare indicators and dietary aspects in relation to childhood stunting. Management of missing data was also ignored.

Conclusions

This study showed that both individual- and community-level factors determined childhood stunting among under-five children in Ethiopia. At the individual level, an increased age of the child, gender parity (being male), smaller size of the child at birth, lower BMI of the mother, poor wealth quintiles of the household, children of mothers with no education, and multiple births were found significant in determining childhood stunting. At community-level, children from communities of Amhara, Tigray, and Benishangul suffer more from childhood stunting as compared to Addis Ababa’s children., Children from Muslim, Catholic and other traditional families had higher log odds of stunting relative to children from the Protestant families. Moreover, children residing in rural Ethiopia were more likely to be stunted relative to urban dwellers. Thus, public health interventions targeting childhood stunting should focus on both the individual and community-level factors linked to maternal nutrition at large and child nutritional status.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey Institutional Data Access/ Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Now it is available and can be obtained from the corresponding author (Mekonnen Haileselassie, Email: mekonnen210@yahoo.com).

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criterion

- BMC:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ECSA:

-

Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- ICC:

-

intra-cluster correlation coefficient

- MOR:

-

Median Odds Ratio

- PCV:

-

Proportional Change in Variance

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Berkman DS, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, Lopez SL, Black MM. Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet. 2002;359:564–57.

SCUK, A life free from hunger: tackling child malnutrition London save the children fund UK, 2012.

Dewey K. Reducing stunting by improving maternal, infant and young child nutrition in regions such as South Asia: evidence, challenges and opportunities. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(Suppl. 1):27–38.

Martorell R, Zongrone A. Intergenerational influences on child growth and undernutrition. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(s1):302–14.

CSA, (Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency). Demographic and health survey, Ethiopia. 2011.

Christiaensen L, Alderman H. Child malnutrition in Ethiopia: can maternal knowledge augment the role of income? Econ Dev Cult Change. 2004;52(2):287–312.

EDHS, Central Statistics Agency. Mini Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2016.

COHA. The Cost of Hunger in Ethiopia: The Social and Economic Impact of Child Undernutrition in Ethiopia Summary Report. 2013.

Liben ML, Abuhay T, Haile Y. Determinants of child malnutrition among agro pastorals in northeastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Health Sci J. 2016;4:15.

Demissie S, Worku A. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6-59 months of age in pastoral community of Dollo ado district, Somali region, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2013;1(4):175–83.

Demographic Ethiopian Health Survey: Addis Ababa. Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: central statistics agency and ORC macro, 2011.

Sisay FT, Sh Z, Lema M, Wubarege S. Prevalence and associated factors of stunting among 6-59 months children in pastoral Community of Korahay Zone, Somali regional state, Ethiopia. J Nutr Disord Ther. 2017. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0509.1000208.

Amare D, Negassie A, Tsegaye B, Assefa B, Ayenie B. Prevalence of undernutrition and its associated factors among children below five years of age in bure town, west Gojjam zone, Amhara National Regional State, Northwest Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7145708.

Ma’alin A, Birhanu D, Melaku S, Tolossa D, Mohammed Y, Gebremicheal K. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6–59 months of age in Shinille Woreda, Ethiopian Somali regional state: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutrition. 2016;2(1):44.

Fikadu T, Assegid S, Dube L. Factors associated with stunting among children of age 24 to 59 months in Meskan district, Gurage zone, South Ethiopia: a case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):800.

Tamiru MW, Tolessa BE, Abera SF. Under nutrition and associated factors among under-five age children of Kunama ethnic groups in Tahtay Adiyabo Woreda. Tigray regional state, Ethiopia: community based study. Int J Nutr Food Sci. 2015;4(3):277–88.

Asfaw M, Wondaferash M, Taha M, Dube L. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):41.

Girma W, Timotiows G. Determinants of nutritional status of women and children in Ethiopia. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ORC Macro; 2002.

Teshome B, Kogi-Makau W, Getahun Z, Taye G. Magnitude and determinants of stunting in children underfive years of age in food surplus region of Ethiopia: the case of west gojam zone. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2009;23(2):99–106.

Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data, vol. 253. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1994. p. 17.

Duncan C, Jones K, Moon G. Context, composition, and heterogeneity: using multilevel models in health research. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:97–117.

CSA, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, The DHS, Program, ICF. Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey. 2016.

Onis M. WHO child growth standards: length/height-forage, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-forheight and body mass index-for-age: methods and development: methods and development. Geneva, Switzerland. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:76–85.

Akombi B, Agho KE, Hall JJ, Wali N, Renzaho A, Merom D. Stunting, wasting and underweight in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):863.

Tiwari R, Ausman LM, Agho KE. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among underfives: evidence from the 2011 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):239.

Bennett DA. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(5):464–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x.

Boco AG. Individual and community level effects on child mortality: an analysis of 28 demographic and health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa; 2010.

Uthman OA, Kongnyuy EJ. A multilevel analysis of effect of neighbourhood and individual wealth status on sexual behaviour among women: evidence from Nigeria 2003 demographic and health survey. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2008;8(1):9.

Midi H, Sarkar S, Rana S. Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics. 2010;13(3):253–67.

Theall K, Scribner R, Broyles S, Yu Q, Chotalia J, Simonsen N, et al. Impact of small group size on neighbourhood influences in multilevel models. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:688–95.

Kamal S. Socio-economic determinants of severe and moderate stunting among under-five children of rural Bangladesh. Mal J Nutr. 2011;17(1):105–18.

Rakotomanana H, Gates GE, Hildebrand D, Stoecker BJ. Determinants of stunting in children under 5 years in Madagascar. Matern Child Nutr. 2016:e12409. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12409.

Ntenda PAM, Chuang Y-C. Analysis of individual-level and community-level effects on childhood undernutrition in Malawi. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;59:380–9.

Dasgupta A, Parthasarathi R, Biswas R, Geethanjali A. Assessment of under nutrition with composite index of anthropometric failure (CIAF) among under-five children in a rural area of West Bengal. Indian J Community Health. 2014;26(2):132–8.

Khan REA, Raza MA. Determinants of malnutrition in Indian children: new evidence from IDHS through CIAF. Qual Quant. 2016;50(1):299–316.

Marriott BP, White A, Hadden L, Davies JC, Wallingford JC. World Health Organization (WHO) infant and young child feeding indicators: associations with growth measures in 14 lowincome countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(3):354–70.

Yadav H, Lee N. Maternal factors in predicting low birth weight babies. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68(1):44–7.

Gebremedhin M, Ambaw F, Admassu E, Berhane H. Maternal associated factors of low birth weight: a hospital based cross-sectional mixed study in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2015;15(1):222.

Magadi MA. Household and community HIV/AIDS status and child malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from the demographic and health surveys. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(3):436–46.

Adekanmbi VT, Kayode GA, Uthman OA. Individual and contextual factors associated with childhood stunting in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(2):244–59.

World Health Organization. WHO multicentre growth reference study group: WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. Geneva: WHO 2006;2007.

Fenske N, Burns J, Hothorn T, Rehfuess EA. Understanding child stunting in India: a comprehensive analysis of socio-economic, nutritional and environmental determinants using additive quantile regression. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78692.

Demilew YM, Abie DD. Undernutrition and associated factors among 24–36-month-old children in slum areas of Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:79.

Olack B, Burke H, Cosmas L, Bamrah S, Dooling K, Feikin DR, et al. Nutritional status of under-five children living in an informal urban settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(4):357.

Pillai VK, Ortiz-Rodriguez J. Child malnutrition and gender preference in India: the role of culture. Health Sci J. 2015;9:6–8.

Jayachandran S, Kuziemko I. Why do mothers breastfeed girls less than boys? Evidence and implications for child health in India. Q J Econ. 2011;126(3):1485–538.

Prendergast AJ, Humphrey JH. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Paediatrics and international child health. 2014;34(4):250–65.

Abuya BA, Ciera J, Kimani-Murage E. Effect of mother’s education on child’s nutritional status in the slums of Nairobi. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1):80.

Kimani-Murage EW, Muthuri SK, Oti SO, Mutua MK, van de Vijver S, Kyobutungi C. Evidence of a double burden of malnutrition in urban poor settings in Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129943.

Frost MB, Forste R, Haas DW. Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bolivia: finding the links. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):395–407.

Abrams B, Selvin S. Maternal weight gain pattern and birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(2):163–9.

Musbah E, Worku A. Influence of maternal education on child stunting in SNNPR, Ethiopia. Central Afr J Public Health 2016;2(2):71–82.

Felisbino-Mendes MS, Villamor E, Velasquez-Melendez G. Association of maternal and child nutritional status in Brazil: a population based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87486.

Nguyen P, Sanghvi T, Kim SS, Tran LM, Afsana K, Mahmud Z, et al. Factors influencing maternal nutrition practices in a large scale maternal, newborn and child health program in Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0179873. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179873.

Levay V, Mumtaz Z, Rashid F, Willows N. Influence of gender roles and rising food prices on poor, pregnant women's eating and food provisioning practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Reprod Health. 2013;10:53.

Mkandawire E, Hendriks S. A qualitative analysis of men’s involvement in maternal and child health as a policy intervention in rural Central Malawi. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18:37.

Chowdhury MRK, Rahman MS, Khan MMH, Mondal MNI, Rahman MM, Billah B. Risk factors for child malnutrition in Bangladesh: a multilevel analysis of a nationwide populationbased survey. J Pediatr. 2016;172:194–201.

Zere E, McIntyre D. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2003;2(1):7.

Kandala N-B, Madungu TP, Emina JB, Nzita KP, Cappuccio FP. Malnutrition among children under the age of five in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): does geographic location matter? BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):261.

Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Ezzati M, Group NIMS. Children’s height and weight in rural and urban populations in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(5):e300–e9.

Kia AA, Rezapour A, Khosravi A, Abarghouei VA. Socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition in Under-5 children in Iran: evidence from the multiple Indicator demographic and health survey, 2010. J Prev Med Public Health. 2017;50(3):201.

García Cruz LM, González Azpeitia G, Reyes Súarez D, Santana Rodríguez A, Loro Ferrer JF, Serra-Majem L. Factors associated with stunting among children aged 0 to 59 months from the central region of Mozambique. Nutrients. 2017;9(5):491.

Ezeh A, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D, Chen Y-F, Ndugwa R, Sartori J, et al. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):547–58.

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) and Demographic Health program for providing us to use the 2016 EDHS dataset through their archives (archive@dhsprogram.com). Many thanks also go to Dr. Birhanu Hadush for his valuable comments.

Funding

There is no source of funding for this research. All costs were covered by researchers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FGK conceived the general research design and participated in data analysis, interpretation and wrote the first draft. AMB coordinated the study, reviewed the manuscript and contributed with critical comments and drafted the paper; MHW participated in research design, data analysis and refined the general research idea. HTA participated in research design, reviewed the manuscript, and contributed comments. OS reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Review committee of Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences (Ref. number 1245/2018). The data was obtained from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey Data (Data Archivist) for research purpose after the objective of the study was explained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fantay Gebru, K., Mekonnen Haileselassie, W., Haftom Temesgen, A. et al. Determinants of stunting among under-five children in Ethiopia: a multilevel mixed-effects analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Pediatr 19, 176 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1545-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1545-0