Abstract

Background

Adolescent communication with parents is paramount to reduce sexual health problems. Currently, there is a shortage of information on adolescent-parent communication in Ethiopia in general and study area in particular. Thus, this study is intended to determine adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues and its factors among secondary and preparatory school adolescents in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia.

Methods

We used institution based cross-sectional study design. We stratified schools into urban and semi-urban settings. Then, a total of 8 schools were randomly selected from the strata. The sample size was allocated for each stratum. Finally, participants were randomly selected from separate sampling frames prepared for each stratum. We developed structured questionnaire from related literatures to collect data on adolescent-parent communication and its factors. We cleaned and entered data using EPI info version 3.5.3 and exported to SPSS version 20 for descriptive and logistic regression analysis.

Results

The proportion of adolescents who had communicated with their parents was 144 (35.0%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicates that participants’ knowledge about availability of adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services at health facilities [AOR: 0.40, 95% CI: (0.26, 0.62),P-value = 0.001], utilization of adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services [AOR: 0.46, 95% CI: (0.29, 0.72),P-value = 0.001] and respondents’ educational status: being grade 9, [AOR: 3.21, (95% CI: ((1.16, 8.89), P-value = 0.025] and grade 11; [AOR: 2.96, (95% CI: (1.06, 8.30),P- value =0.039] were statistically associated factors affecting adolescents for not communicating with parents on sexual and reproductive health issues.

Conclusion

The findings of our study imply that adolescents were not communicating much with parents about sexual and reproductive health issues even though they were aware of adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services. In addition, promotion of service availability may be important to motivate adolescents to communicate with parents. Contextual and age dependent communication barriers should be further identified. Further research is needed in the area to identify barriers particularly from parent side.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Around 24.5% (1.8 billion) of the world’s population are adolescents and youths aged 10 to 24 years in 2015. Of which, 18% of all adolescents and youths live in Africa. In Ethiopia, more than 35% of the total population is made from adolescents and youths aged 10 to 24 years [1]. This big number is still facing big challenges in sexual and reproductive health and right services. The global community in general; Africa in particular has still a lot of unfinished agenda with regard to major STIs among adolescents. Adolescents, a vulnerable populations have multiple sexual and reproductive health problems including gender inequality, sexual coercion and partner violence, early marriage, polygamy, female genital mutilation, unplanned pregnancies, closely spaced pregnancies, abortion, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS [2,3,4,5].

Researches indicate that adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa were not well informed about sexual and reproductive health matters, because their major sources of information are friends. Other informal sources like parents had got low attention while parents could be a key strategy to reach adolescents. Although, parents were themselves often uninformed and preferred that their children learn from teachers or health-care workers, teacher /health care professionals in turn believed that parents should have the primary responsibility for providing information [6, 7].

As long as adolescents are from diverse community, inclusive behavioral interventions are needed that take account of the social context, attempt to modify social norms to support uptake and maintenance of behavior change, and tackle the structural factors that contribute to risky sexual behavior [7]. As evidences suggest, adolescent-parent communication may be one proximate strategy among several strategies that improves healthy sexual and reproductive health behavior [8,9,10]. The universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services set by the united nation would not be realized unless we reach adolescents through various interventions including parents in low- and middle-income countries [11, 12].

Adolescents need adults—especially parents, who will connect with them, communicate with them, spend time with them, and show a genuine interest in them. Despite adolescents often have difficulty in communicating about sexuality with their parents; it helps them to establish individual values to healthy sexual behavior [13]. Talking with adolescents about sex-related topics including abstinence, improved contraception, how to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is a positive parenting practice that has been widely researched [13, 14].

Researches have showed that adolescent–parent communication about sexual issues can reduce adolescents’ sexual risk [14, 15]. An HIV/AIDS intervention research established that parent-adolescent communication on sex-related issues improved youth’s condom use skills and self-efficacy [16].Given that parental factors are resolved through helping parents [17], sexual communication with parents, particularly mothers, plays a role in having safer sex behavior [8].

However, adolescent communication about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues is affected by social norms and taboos related to gender and sexuality. These factors create a culture of silence, particularly for adolescent girls, in asking, obtaining information, discussing, and expressing their worries about SRH [18]. Similarly, cultural and religious beliefs of parents that adolescents are too young to discuss about sexual issues and unfavorable environment for discussion hinder adolescent-parent communication on sexual health issues [9, 19].

In Ethiopia, evidences show that sex, age, lack of parental interest to discuss, feeling ashamed and cultural unacceptability to talk about sexual matters [19,20,21,22] were factors affecting adolescent-parent communication. These may contribute to low utilization of adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services (AYFSRHs) in the country.

In Ethiopian context of ethnic and cultural diversity, adolescent-parent communication about sexual and reproductive health issues is an important factor that may reduce engagement in risky sexual behavior. As to our knowledge, there is limited information regarding parent- adolescent communication and its factors among adolescents attending high school. Therefore, the objective of the study is to determine adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues and its factors among high school adolescents aged 15 to 19 years old.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted in secondary and preparatory schools located in Southern Ethiopia; Hadiya Zone. The Zone has a total of 42 secondary schools (35 governmental and 7 private) during the study. Of which, 9 and 33 schools are situated in urban and semi-urban settings, respectively. A total number of students enrolled in all the schools is 60,532 (31,920 males and 28,612 females) in 2016.

Despite remarkable progress has been made in increasing access to adolescent-friendly reproductive health services, more efforts are needed to shrink wide range of SRH problems in Ethiopia in general and study area in particular. The strategy that is being currently implemented in the study area lacks focus on adolescent-parent communication particularly on sexuality and sensitive reproductive health issues due to various sociocultural and health service related factors [23].

Study design and period

We used institution based cross sectional study design from April to August; 2016.

Study participants

The source population was all adolescents whose age ranges from 15 to 19 years attending their secondary schools. The study population included adolescents (15–19 years old) who had the chance of being randomly selected from the source population. Adolescents whose age is less than 15 years were excluded from the study due to the fact that they might not provide accurate information with regard to sexual and reproductive health issues.

Sample size calculation

The sample size for the study was estimated by using single population proportion formula at 95% confidence level (CI), Z (1-ά/2) = 1.96), an expected proportion of adolescent-parent communication, 59.1%, from the study conducted in southern Ethiopia [24] and, 5% margin of error. Using the above assumptions, the sample size was calculated as follows.

We considered none-response rate of 15% in the estimation of the minimum sample size required for the study. Therefore, the final sample size was 428 adolescents in the age group 15–19 years.

Sampling techniques

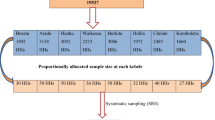

First we stratified schools into urban and semi-urban secondary schools. Once we stratified schools, we randomly selected 2 schools from urban and 6 schools from semi-urban areas. Then the calculated sample size was proportionally allocated to randomly selected schools by size of students in each school. Again, we prepared another strata based on students’ grades in the selected schools and proportional sample of students was allocated to each stratum. For each stratum (student’s grade), we prepared sampling frame comprising students whose age ranges from 15 to 19 years. Finally, we randomly selected study participants independently from the prepared sampling frame prepared using lottery method in each stratum until the allocated sample size is reached.

Data collection and quality procedures

We developed structured questionnaire by reviewing related literatures and previous studies in accordance with the stated objectives of the study. Relevant contents have been extracted from standardized questionnaire developed by John Cleland and included in our questionnaire [25]. The questionnaire was first prepared in English, translated into Amharic and then re-translated back to English to check its consistency. We conducted a pretest on 5% of our sample size among students enrolled in secondary schools (private and government) other than the study setting. We corrected and revised the questionnaire based on the gaps identified during the pretest. We used self-administered data collection technique to gather data. We recruited four supervisors and oriented them how to supervise the data completion procedures. Informed verbal consent from the participants [18 or older age] and assent and informed parental consent (less than 18 years of old) was obtained before the questionnaire have been completed. The completed questionnaire was checked for its consistency and completeness.

Study variables

Data were collected on independent variables like socio-demographic and economic, socio-cultural, religion, ethnicity, participants’ knowledge about and attitude towards sexual and reproductive health issues, individual/personal factors related to reproductive health service, and other sexual and reproductive health service factors. Adolescent-parent communication about sexual and reproductive health issues/ behavior is a dependent or an outcome variable.

Operational definitions

Parents

Refer to household members of the study participants to encompass WHO definition “all those who provide significant and/or primary care for adolescents, over a significant period of the adolescent’s life, without being paid as an employee,” [17] such as biological parents (father, mother), grandparents, elder sister/brothers and any other caretakers.

Parental communication

Refers to a discussion made among the study participants and parents on at least one of the sexual and reproductive health issues (sexuality and sexuality education, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STI), unintended pregnancy and safe abortion, antenatal care, sexual violence and right and so on) in their life time.

Adolescent

Refers to study participants in the age range from 15 to 19 years.

Mother/father

Applies for both the students’ biological parents and guardians.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Data were cleaned and entered to EPI info version 3.5.3 [26] and exported to SPSS version 20 [27] for descriptive and logistic regression analysis. We used descriptive data analysis techniques to describe the distribution of factors for adolescent-parent-communication among adolescents. We employed logistic regression to identify associated factors for adolescent-parent communication about sexual and reproductive health issues. We computed odds ratio with 95% CI to show the strength of the association between the adolescent-parent communication and associated factors. All variables which showed statistically significant results (P-value < 0.05) with adolescent-parent communication in bivariate logistic regression were taken to multivariate logistic regression model. Thus, the independent effect of each explanatory variable on an outcome variable was determined while controlled for others.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

Out of 428 participants, 411 study participants were considered for analysis which gave the overall response rate of about 96%. The study participants were in the age range of 15 to 19 years with mean age of 17.73 + 1.18 SD years. Among 411 study participants, 210 (51.1%) were males. Majority of the participants, 244 (59.4%), were residents living in the rural parts of the Hadiya Zone and most of them, 287 (69.8%), were living together with their parents. The mean monthly family income of the study participants was 72.70 + 62.93SD USD. Thirty eight (9.2%) of the study participants had their own average monthly income of 11.92 + 10.08 SD USD. The distribution of socio-demographic characteristics of the participants is depicted bellow (Table 1).

Adolescent –parent communication about sexual and reproductive health issues and risk behaviors

The proportion of adolescents who had communicated with their parents regarding sexual and reproductive health issues was 144 (35.0%). Of which, females represent 75(52.1%) followed by males 69 (47.9%). Participants’ brothers were the most preferred family members 46 (11.2%) by adolescents to communicate with about sexual and reproductive health issues followed by fathers which accounted for 42 (10.2%). Of the 144 adolescents, 123 (85.4%), 115(79.9%) and 70 (48.6%) had accounted for HIV counseling and testing, contraception and/or condom, and sexually transmitted infections respectively. Seventy nine (19.2%) of participants had experienced sexual intercourse at least once in their life time. The mean age at which they experienced their first sexual intercourse was 15.89 + 1.57 SD years. Among respondents who had sexual intercourse, self-sexual-drive was the leading, 54 (68.4%) motivator for the adolescents to engage in sexual activity followed by peer pressure 36 (45.6%). Thirty three (8.0%) of the study participants used at least one substance. Among these, 17 (51.5%) of substance users had been using khat followed by alcohol, 12(36.4%) (Table 2).

Individual factors on sexual and reproductive health services

Majority, 330 (80.3%), of the participants had information about adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services (AYFSRHs). However, less than half, 179 (43.6%) of the participants had information about availability of AYFSRHs at nearest health facilities/youth centers. Among participants who had information, 229 (69.4%), 209 (63.3%) and 98 (29.7%) had been informed about HIV/AIDS counseling and testing, contraception and/or condom services, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections respectively. Of the participants who had been informed about AYFSRH, 291 (88.2%) believed that utilization of the service promotes healthy sexual and reproductive behavior. Seventy (17.0%) of study participants reported that they did not get AYFSRHs from the nearest health facilities/youth centers despite of their intention to use. The two major reasons cited for not using the services were inconvenient service time, 19(27.1%), followed by long waiting time, 16(22.9%) (Table 3).

Factors associated with adolescent-parent communication about sexual and reproductive health issues

As observed from multivariate logistic regression analysis, participants’ knowledge about the service availability, utilization of AYFSRHs and respondents’ education were significantly associated with adolescent-parent communication. Those who had no information about availability of AYFSRHs at health facilities were 60% less likely to communicate with their parents about sexual and reproductive health issues [AOR: 0.40, 95% CI: (0.26, 0.62), P-value = 0.001] than those who had. Likewise, those who had not utilized AYFSRHs were about 54% less likely to communicate with their parents when compared to those who had utilized the service [AOR: 0.46, 95% CI: (0.29, 0.72), P-value = 0.001]. Lower grade (grade 9) participants were about 3 times more likely to communicate about sexual and reproductive issues as compared to higher grades participants (grade twelve and above) [AOR: 3.21, 95%CI: (1.16, 8.89),P- value = 0.025]. Moreover, participants from grade 11 were about 3 times more likely to communicate than those from grade twelve and above [AOR: 2.96, 95%CI: (1.06, 8.30), P- value =0.039] (Table 4).

Discussion

The practice of risky sexual behaviors of adolescents results in sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancies, poor sexual engagement and delayed or absence of early management of adverse outcomes of sexuality and reproductive health problems. Evidences suggest that adolescent-parent communication about sexuality and reproductive health issues helps adolescents avoid the experience of such a risky sexual and reproductive health behaviors. Therefore, this study addresses adolescent-parent communication and factors associated with sexual and reproductive health issues among adolescents attending their secondary and preparatory schools. Consequently, it might give insights to the policy programmers for the development of appropriate interventions.

Our study presents that only 35.0% of adolescents had communicated with their parents. This finding is less than the findings of the studies conducted in Debremarkos, Northwest Ethiopia, 36.9% [28], Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia, 59.1% [24], Dire Dawa, East Ethiopia, 37% [21] and Mekele, North Ethiopia, 43.5% [29]. This could be due to the fact that majority of the study participants (59.4%) in our study reside in rural settings which might have reduced their exposure to sexual and reproductive health information and this might have subsequently reduced the opportunity to communicate with their parents.

In this study, adolescent-parent communication is nearly two folds lower than the finding from hospital based study on condom use, 76%, in America [30]. This could be explained by limited exposure of adolescents and parents to reproductive health information to utilize the services in less developed nations when compared to those in well developed nations. In addition, as evidenced by a literature [31], low level of parental connectedness as a result of low awareness about sexual and reproductive health issues and lack of close supervision contribute for low level of parental communication.

However, our finding is slightly greater than the study findings from northwest Ethiopia, Awabel Woreda, 25.3% [20], west Ethiopia, East Wollega Zone, 32.5% [22] and east Ethiopia, Harar 28.8% [32] and India, 29% [33]. The observed difference could be due to the fact that our study is more recent than the aforementioned studies in which both parents and adolescents might have had better access to promotional activities about sexual and reproductive health information. With regard to communication preferences, participants’ brothers were the most preferred to other members of the family about sexual and reproductive health issues. This finding contradicts with the finding from northwest Ethiopia, Awabel Woreda [20] where most of the participants, 31.4% preferred mothers to other members of their family to communicate with about reproductive health matters.

Many school based interventions have been realized on the ground such as family planning, prevention and control of STI, HIV/AIDS, and gender violence and so on in Ethiopia. On the contrary to the available interventions, our finding implies that adolescent-parent communication had low achievement. Though several factors might contribute for the low achievement, parental factors played a role for low adolescent-parent communication as stated in the study done in Ethiopia [29] and Uganda [34]. Thus, the Ethiopian adolescent and youth friendly service programs should have to go a long distance to achieve better coverage in adolescent-parent communication.

As observed in our descriptive analysis, 19.7% of adolescents had not ever heard about AYFSRHs. This figure is lower than the study done in Debremarkos, northern Ethiopia [28] which accounted for, 37.6%. More than half, 56.4% of study participants reported that they had never been informed about the availability of adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services in the health facilities. Whatever the case, the finding indicated that there had been poor promotional activities about adolescent and youth friendly services in schools with the intention to reach adolescents. As stated by the World Health Organization [7, 9] school based sexual and reproductive health promotion is vital in reaching adolescents.

The practice of risky sexual behavior had been analyzed for the study participants. Accordingly, 19.2% of the study participants were sexually active at the mean age of 15.89 + 1.57 SD years during their first sexual intercourse. Our finding indicated that participants had earlier sexual experience when compared to the study finding in Gamo Gofa [35], but delayed than the finding from the study in Debremarkos, North Ethiopia [28]. Eight percent of the study participants abused at least one substance. This finding is less than the study finding in Bale, South West Ethiopia, 34.8% [36], Woreta Town, Northwest Ethiopia, 47.9% [37] and Harar, East Ethiopia [32]. This might be due to cultural differences and variations in associated interventions with respect to sexual and reproductive health problems among the study settings.

Those adolescents who had no information about availability of AYFSRHs at health facilities were less likely to communicate with their parents about sexual and reproductive health issues. This is supported by the finding from the study in Debremarkos, North Ethiopia [26]. This could be due to the fact that absence of information about the availability of the service might have influenced the ability of the adolescents to communicate with their parents. Regarding the service utilization, those adolescents who had not utilized AYFSRHs were less likely to communicate with their parents when compared to those who had utilized the service. This could be reasoned out that adolescents who had experience in utilizing AYFRHs might have been informed more about the importance of parental communication.

Lower grade (grade 9) participants were more likely to communicate about sexual and reproductive issues as compared to higher grades (twelve and above). Our finding was in line with that of Debremarkos, North Ethiopia [26]. Whereas, it disagrees with the findings in Awabel, North Western Ethiopia [20], Mekele, Northern Ethiopia [28] and Harar, Eastern Ethiopia [32]. This might be due to differences in culture and implementation of school-based sexual and reproductive health interventions. In our study other socio demographic factors were not statistically significant with parent-adolescent communication about sexual and reproductive health issues (Table 4). However, sex and age of the adolescents were factors influencing adolescent parent communication in other studies [19,20,21,22].

Conclusion

The findings of our study imply that adolescents were not communicating much with parents about sexual and reproductive health issues even though they were aware of adolescent and youth friendly sexual and reproductive health services. In addition, promotion of service availability may be important to motivate adolescents to communicate with parents. Contextual and age dependent communication barriers should be further identified. Further research is needed in the area to identify barriers particularly from parent side.

Limitation of the study

Our study did not address the parent side factors for adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- AYFRHs:

-

Adolescent and Youth Friendly Reproductive Health Services

- HIV:

-

Human Immune Deficiency Virus

- SNNPR:

-

South Nations, Nationalities and People Regional State

- SRH:

-

Sexual and Reproductive Health

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition. New York; 2015. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-2015-revision.html.

Adolescents health risks and solutions fact sheet [Inter]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions. Accessed 17 Jan 2017.

Delany-Moretlwe S, Cowan FM, Busza J, Bolton-Moore C, Kelley K, Fairlie L. Providing comprehensive health services for young key populations: needs, barriers and gaps. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(2 Suppl 1):19833. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.2.19833.

United Nations Children’s Fund. Turning the tide against AIDS will require more concentrated focus on adolescents and young people. Adolescent and youth people current progress. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/.

UNAIDS/UNICEF. A progress report all in to end the adolescent aids epidemic. New York; 2016. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/aids/files/ALL_IN_2016_Progress_Report_6_16_17.pdf.

The sexual and reproductive health of young adolescents in developing countries: Reviewing the evidence, identifying research gaps, and moving the agenda. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, Singh S, Hodges Z, Patel D, Bajos N. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet Sex Reprod Health Series. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69479-8.

Laura Widman, Sophia Choukas Bradley, Seth M. Noar, Jacqueline Nesi, Kyla Garrett. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):52–61. Available from: jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2468100.

Promoting adolescent sexual and reproductive health through schools in low income countries: an information brief. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

Advocates for Youth. Parent-Child Communication fact sheet: Promoting Sexually Healthy Youth. Wshington DC; 2010. Available from: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/storage/advfy/documents/parent%20child%20communication%202010.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2016.

United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Internet]. New York: 2015. Available from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E. Accessed 2 Jan 2017.

Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1.

DeVore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17:460–5.

Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A. Parent Adolescent Communication about Sex in Latino Families: A guide for practitioners. National Campaign to prevent teen and unplanned pregnancy. 2008.

Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Lee J, McCarthy K, Michael SL, Pitt-Barnes S, Dittus P. Paternal influence on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: a structured literature review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1313–25.

Wang B, Stanton B, Deveaux L, Li X, Koci V, Lunn S. The impact of parent involvement in an effective adolescent risk reduction intervention on sexual riskcommunication and adolescent outcomes. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(6):500–20.

WHO. Helping parents in developing countries improve adolescents’ health. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

Svanemyr J, Amin A, Robles OJ, Greene ME. Creating an enabling environment for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a framework and promising approaches. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1 Suppl):S7-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.011.

Motsomi K, Makanjee C, Basera T, Nyasulu P. Factors affecting effective communication about sexual and reproductive health issues between parents and adolescents in zandspruit informal settlement, Johannesburg, South Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:120. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.25.120.9208.

Ayehu A, Kassaw T, Hailu G. Young people’s parental discussion about sexual and reproductive health issues and its associated factors in Awabel Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Reprod Health. 2016;13(19).

Ayalew M, Mengistie B, Semahegn A. Adolescent - parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues among high school students in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Reprod Health. 2014;11:77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-77.

Tesso DW, Fantahun MA, Enquselassie F. Parent-young people communication about sexual and reproductive health in E/Wollega Zone, West Ethiopia: Implications for interventions. BMC Reprod Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-9-13.

FMOH. Health Sector transformation Plan 2015/16–2019/20. Addis Ababa; 2015.

Yohannes Z, Tsegaye B. Barriers of Parent-Adolescent Communication on Sexual and Reproductive Health Issues among Secondary and Preparatory School Students in Yirgalem, Town, South Ethiopia. Fam Med Med Sci Res. 2015;4:181. https://doi.org/10.4172/2327-4972.1000181.

WHO. Asking young people about sexual and reproductive behaviors: Illustrative questionnaire for interview-surveys with young people [Internet]: John Clevland: Geneva. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/adolescence/questionnaire/en/. Accessed 4 Feb 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epi™ Info for windows. Version 3.5.3. Atlanta: CDC; 2012.

IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk: IBM Corp; 2011.

Shiferaw K, Getahun F, Asres G. Assessment of adolescents’ communication on sexual and reproductive health matters with parents and associated factors among secondary and preparatory schools’ students in Debremarkos town, north West Ethiopia. BMC Reproductive Health. 2014;11:2.

Melaku YA, Berhane Y, Kinsman J, Reda HL. Sexual and reproductive health communication and awareness of contraceptive methods among secondary school female students, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:252. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-252.

Wendy H, Larry KB, Celia ML, Harrison K, Kirsten S, Ralph DC, Geri D. Parent-adolescent sexual communication: associations of condom use with condom discussions. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9468-z.

Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, Peskin MF, Flores B, Low B, House LD. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:23–41.

Yadeta TA, Bedane HK, Tura AK. Factors affecting parent-adolescent discussion on reproductive health issues in Harar, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Environ Public Health. 2014.

Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Sarah W. Sexual communication between early adolescents and their dating partners, parents, and best friends. J Sex Res. 2014;51(7):731–41.

Muhwezi WW, Katahoire AR, Banura C, Mugooda H, Kwesiga D, Bastien S, et al. Perceptions and experiences of adolescents, parents and school administrators regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in urban and rural Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:110.

Tilahun M, Ayele G. Factors associated with age at first sexual initiation among youths in Gamo Gofa, south West Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:622.

Dida N, Kassa Y, Sirak T, Zerga E, Dessalegn T. Substance use and associated factors among preparatory school students in bale zone, Oromia regional state, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Harm Reduct J. 2014;11:2.

Birhanu AM, Bisetegn TA, Woldeyohannes SM. High prevalence of substance use and associated factors among high school adolescents in Woreta town, Northwest Ethiopia: multi-domain factor analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1186.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hossana College of Health Sciences’ research and community service for giving us this opportunity to conduct this research activity. We appreciated our college institutional review board members for their commitment to subsequently review and approve the research. We are also grateful for students from all selected schools for participation in the study, data collectors, school administrators and teachers for their cooperation during the entire process of data collection.

Funding

Hossana College of Health Sciences funded the research under the budget code of 6253. The college approved the research proposal and provided ethical clearance through the research ethical approval committee. The college supervised the overall research activities (data collection, analysis) as per the guidelines and agreements signed between the authors and the research and publication core process owner.

Availability of data and materials

All data are within a manuscript. However, data set is available from authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the college.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS, BB and HD: Wrote the proposal, participated in data collection, analysed the data and drafted the paper. HY and YS: Edited, commented and approved the proposal, participated in data analysis and revised subsequent draft of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

KS: MPH in sexual and reproductive health student fellowship; and worked as a lecturer in department of health extension services.

BB: MPH in Human Nutrition students fellowship; worked as team coordinator in department of health extension service and worked as a lecturer in department of health extension services.

HD: MPH in general public health; lecturer in department of health extension services and a researcher in Hossana College of Health Sciences.

YS: MPH in sexual and reproductive health specialist; coordinator of in-service training center of health professionals; Lecturer in department of midwifery and reproductive health; and a researcher in Hossana College of Health Sciences.

HY: MPH in Epidemiology specialist; coordinator of Health Sciences Education Development Center (HSEDC); Lecturer in department of health information technology professionals and a researcher in Hossana College of Health Sciences.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board of the Hossana College of Health Sciences reviewed and approved the research protocol. Official letter of permission was also obtained from the zonal education department, Woreda education officials and respective school administrators. Information about the objective of the study, confidentiality issues and the respondent’s autonomy was explained to the participants and parents/guardian of participants bellow 18 years old just before the beginning of data collection. We received written consent from each study participant whose age was 18–19 years old and parental consent for study participants who are below 18 years old to ensure voluntary participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kusheta, S., Bancha, B., Habtu, Y. et al. Adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues and its factors among secondary and preparatory school students in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: institution based cross sectional study. BMC Pediatr 19, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1388-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1388-0