Abstract

Background

Excess weight gain in infancy and childhood is associated with increased risk of subsequent obesity. Identifying patterns of infancy and childhood weight gain associated with subsequent obesity or overweight status could help identify children at highest risk. Thus, we examined patterns of infancy and early childhood BMI in relation to mid-childhood overweight and obesity status.

Methods

In a prospective cohort of 215 children from Cincinnati, OH (born: 2003–2006), we measured weight and length or height at ages 4 weeks and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years. We calculated BMI z-scores using World Health Organization references. Using linear fixed effect models, we estimated mean BMI at each age and rates of change in BMI between ages 4 weeks and 5 years by children’s overweight and obesity status at age 8 years, assessed with BMI z-scores or bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA).

Results

Children who became overweight (BMI, n = 51 and BIA, n = 37) or obese (BMI, n = 22 and BIA, n = 29) at age 8 years had greater BMI at all ages compared to normal weightchildren. Children who were overweight had similar rates of change in BMI as children who were lean. Children who were obese had greater gains in BMI between age 4 weeks and 5 years, with the most rapid gains in the first 2 years.

Conclusions

Results from this study of modest sample size, suggest that adiposity patterns in the first 5 years of life are related to subsequent childhood overweight and obesity risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Childhood obesity is a major global public health threat. Globally, 5.6% of girls and 7.8% of boys were obese in 2016 [1]. In the United States (US), 17% of children were obese and another 15% were overweight in 2010 [2]. Childhood obesity increases the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and later life obesity, and has adverse effects on pulmonary, musculoskeletal, and psychosocial functioning [3,4,5]. There is a compelling need to prevent childhood obesity, since there are few effective non-pharmacological or non-surgical interventions to reduce excess adiposity [6].

Understanding the natural course of adiposity during infancy and childhood may help identify obesity risk factors or periods of heightened susceptibility. Previous studies have reported that earlier adiposity rebound, crossing major weight centiles during the first 2 years of life, and trajectories of rapid weight gain during infancy and childhood BMI are associated with increased childhood and adulthood adiposity and risk of obesity [5, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. However, few studies have examined these patterns among US children using measures of body composition, like bioelectric impedance, to define later childhood overweight or obesity status [13].

To improve our understanding of the patterns of adiposity associated with risk of childhood obesity and overweight among US children, we used data from 215 children with 1070 serial anthropometry measures from ages 4 weeks to 5 years to determine if overweight or obese status at age 8 years was associated with BMI or changes in BMI in the first 5 years of life. We hypothesized that children who were overweight or obese at age 8 years would have more rapid increases in BMI in the first 5 years of life compared to children who were lean.

Methods

Study participants

We used data from the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study, a prospective cohort study designed to examine if and how early life environmental chemical exposures influence childhood health. Details regarding eligibility criteria, enrollment, follow-up, and assessments have been previously published [18]. Between March 2003 and January 2006, we recruited pregnant women from nine prenatal care clinics affiliated with three Cincinnati, Ohio area hospitals. At enrollment, women were eligible for the study if they were: 1) ≥ 18 years old, 2) living in a home built before 1978, 3) 16 ± 3 weeks of gestation, 4) no history of HIV infection, and 5) not taking any medications to treat thyroid disorders and seizure. All women provided written informed consent for themselves and their children after the study protocols were explained by research assistants. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and cooperating delivery hospitals.

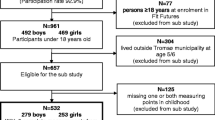

Of 389 live-born singletons, 219 (56%) completed the follow-up visit at age 8 years and had anthropometry data from this visit and at least one visit before age 8 years (Additional file 1: Supplemental Figure 1). Four children were missing relevant covariate data, leaving 215 children who provided 1070 repeated anthropometry measures for this analysis.

As we previously reported, participants who completed follow-up at age 8 years were similar to the original cohort in terms of baseline characteristics [18]. Most baseline characteristics of mother-child pairs who did and did not complete follow-up at age 8 years were similar, although there was a greater proportion of non-Hispanic Black women who completed follow-up than those who did not complete follow-up (36 vs. 27%) (Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1).

Anthropometry measurements

Trained research assistants obtained anthropometric measurements when children were 4 weeks and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years old. At all seven visits, we measured weight to the nearest 0.01 kg with the child dressed in a dry diaper or undergarments using a ScaleTronix scale. At 4 weeks and 1 year of age we measured length to `the nearest 0.1 cm using a length board. At or after age 2 years we measured height to the nearest 0.1 cm using an Ayrton Stadiometer (Model S100) with the child standing straight with heels positioned against the wall without shoes or head coverings. Fifty-five percent of children had all 6 BMI measurements, with 92% having ≥ 3 measures. At age 8 years, we used a Tanita children’s body fat monitor (BF-689) to estimate children’s body fat via bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA).

We calculated age- and sex-specific BMI z-scores at all ages using World Health Organization (WHO) references [19, 20]. At age 8 years, we classified children as normal weight, overweight, or obese using WHO references or bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) [19, 21]. For BMI, we defined normal weight (< 1 standard deviation score), overweight (> 1 to ≤ 2 standard deviation scores), or obese (> 2 standard deviation scores) status at age 8 years using WHO definitions [19]. For BIA, we defined normal weight, overweight, and obese according to age- and sex-specific reference values [21]. We used both BMI and BIA at age 8 years to assess overweight and obesity status because BMI may not accurately reflect adipose tissue mass during childhood [22].

Statistical analyses

We began by describing maternal and child characteristics among children who were normal weight vs. overweight or obese at age 8 years. These characteristics included maternal race (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Other), education (high school or less, some college, and college or greater), marital status (married and unmarried), household income (continuous, US dollars per year), child sex (male and female), and duration of breastfeeding (continuous months). These variables were collected using standardized interviews that were administered by trained research assistants.

Next, we used linear regression models estimated via generalized least squares to estimate mean BMI z-scores and longitudinal changes in BMI z-scores between age 4 weeks and 5 years according to whether children were normal weight, overweight, or obese according to their age 8 year BMI or BIA value. We used the Akaike Information Criterion to identify the best fitting model and modeled BMI z-scores as a function of age, age-squared, and age-cubed terms with an unstructured covariance matrix and no random effects. Specifically, our model took the form:

Where Yij is the BMI z-score for the i-th child at the j-th visit, Ageij is the child age for the i-th child at the j-th visit, OB and OW were indicator terms for overweight and obesity status at age 8 years, and βkXk are additional terms that control for the aforementioned maternal and child characteristics. With this model, we estimated the mean BMI z-score at each age, as well as the annual rate of change in BMI z-score between adjacent measurements in children who were normal weight, overweight, or obese at age 8 years. We used Wald χ2 tests with 4 degrees of freedom to test whether BMI z-score trajectories differed by obesity status at age 8 years. Setting β4 = β5 = β6 = β7= 0 allowed us to compare normal weight vs. overweight trajectories, setting β8 = β9 = β10 = β11= 0 to compare normal weight vs. obese trajectories, and setting β4 − β8 = β5 − β9 = β6 − β10 = β7 − β11=0 to compare overweight and obese trajectories. Because of possible departures from normality induced by selection on the distal outcome (adiposity at age 8 years), all test procedures used robust standard error estimation in 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value calculations.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to verify the robustness of our results. First, we examined whether BMI z-score trajectories varied by child sex, because boys and girls may accrue fat mass at different rates. Second, we excluded infants who were born small for gestational age (n = 23, birth weight < 10th percentile for gestational age and sex) or preterm (n = 18, < 37 weeks gestation) [23].

Results

At age 8 years, 51 (24%) children were overweight, but not obese, and 22 (10%) children were obese, according to WHO definitions. Compared to children who were normal weight at age 8 years, children who were overweight or obese were more likely to have been breastfed for 0 to < 6 months and have mothers who were younger at delivery, non-Hispanic Black, less educated, poorer, and unmarried (Table 1). From ages 4 weeks to 5 years, 8.2–23.2% of children had a BMI z-score > 1 and 1.4–9.4% of children had a BMI z-score > 2 according to WHO definitions (Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 2). A total of 37 (17%) children were overweight and 29 (13%) were obese at age 8 years according to BIA-derived body fat percent.

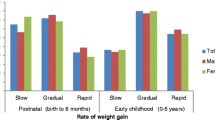

The pattern of BMI z-scores among children who became obese at age 8 years was significantly different compared to children who were normal weight or overweight at age 8 years (Wald χ2 p-values< 0.001). Compared to children who were normal weight at age 8 years, children who were obese had higher BMI z-scores at all ages, including age 4-weeks, and the magnitude of these differences increased as children aged (Tables 2 and 3, Figs. 1 and 2, and Additional file 1: Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Children who became obese at age 8 years had positive rates of BMI z-score change at all ages, but the annual rates of change were greater between 4 weeks and 2 years than between 2 and 5 years.

Adjusted Mean BMI Z-scores from Ages 4 Weeks to 5 Years According to WHO BMI-Derived Child Overweight/Obesity Status at Age 8 Years: The HOME Study a,b,c,d

aAdjusted for maternal race, education, marital status, age at delivery, household income, and breastfeeding duration

bOverweight and obesity status at age 8 years was defined as having age- and sex-specific BMI z-scores >1 and >2 according to WHO references, respectively

c142, 51, and 22 children were lean, overweight, or obese at age 8 years, respectively, and they contributed 732, 235, and 103 repeated BMI z-scores

dShading represents the 95% confidence interval

Adjusted Mean BMI Z-scores from Ages 4 Weeks to 5 Years According to Bioelectric Impedance-Derived Child Overweight/Obesity Status at Age 8 Years: The HOME Study a,b,c,d

aAdjusted for maternal race, education, marital status, age at delivery, household income, and breastfeeding duration

bOverweight and obesity status at age 8 years was defined as having age- and sex-specific body fat percent standard deviation scores >1 and >2, respectively [21]

c149, 37, and 29 children were lean, overweight, or obese at age 8 years, respectively, and they contributed 761, 177, and 132 repeated BMI z-scores

dShading represents the 95% confidence interval

Children who were overweight at age 8 years had statistically significantly higher BMI z-scores than normal weight children at all ages, but their pattern of change in BMI z-scores was not significantly different than normal weight children (Wald χ2 p-value = 0.84). Children who became overweight at age 8 years had similar BMI z-scores as obese children at ages 4 weeks and 1 and 2 years, but their mean BMI z-score plateaued after age 2 years and was statistically significantly lower at ages 3, 4, and 5 years compared to children who became obese (Tables 2 and 3). The annual rates of change in BMI z-scores among children who became overweight at age 8 years were positive before age 2 years and then approximately 0 after age 2 years (Tables 2 and 3).

When we examined BMI z-score trajectories according to normal weight, overweight, and obesity status at age 8 years assessed with BIA, our results were similar to those when we used BMI z-score to define adiposity at age 8 years (Fig. 2, Table 3, Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 4). There were no notable differences in the patterns of child BMI z-score by overweight/obesity status when we stratified by child sex (results not shown). Our results were not appreciably different when we excluded children who were small for gestational age or preterm (results not shown).

Discussion

In this cohort, we observed that children who were overweight or obese at age 8 years had higher BMI z-scores between 4 weeks and 5 years of age than their normal weight peers. Compared to children who were normal weight or overweight at age 8 years, children who were obese had greater gains in BMI during the first 5 years of life with the greatest gains in BMI during the first 2 years of life. Children who were overweight had similar rates of BMI gains as children who were normal weight, but they had higher BMI than normal weight children at all ages, including at age 4 weeks.

Our finding of more rapid gains in adiposity in the first 2 years of life among children who became obese is consistent with prior studies observing increased risk of later life obesity among infants who grow rapidly in the first 2 years of life [8,9,10,11, 24]. Additional studies have tried to identify patterns and trajectories of early childhood adiposity associated with risk of obesity in child- or adulthood with relatively consistent results [12,13,14,15, 25]. Our results are generally consistent with the results of most prior studies [12, 13, 15, 25]. Glavin et al. found an increased risk of obesity and overweight at age 8 years among Norwegian children with more rapid gains in adiposity during infancy and more adiposity in later childhood, findings consistent with our own [12]. In a study of US children, greater gains in adiposity in the first 3 years of life were associated with measures of body composition at age 6–10 years; these associations were strongest for adiposity gains between age 2–3 years [13]. A study of French adults reported that BMI trajectories between birth and age 10 years characterized by above average adiposity were positively associated with both BMI and waist circumference in adulthood [15]. In a longitudinal study of Chilean children, prevalent, but not incident obesity and overweight status in the first 4 years of life was associated with increased risk of being overweight or obese at age 7 years [25]. Finally, and in contrast to the current and prior work, BMI in adults born and living in India was more strongly correlated with BMI and increases in BMI in later childhood [14]. However, a large proportion of this cohort was underweight during childhood, which may explain these results.

Children who became overweight in this cohort did not experience more rapid gains in BMI in the first 5 years of life compared to lean children; however, they did have higher BMI at all ages, with these elevations becoming relatively stable at ages 3, 4, and 5 years. A prior study reported that children who were overweight at age 5 years had 4-times the risk of being obese by age 14 years compared to children who were lean [5]. Thus, children who are overweight in early childhood, but not obese, represent a susceptible sub-population who are at higher risk of developing obesity. Additional research is necessary to understand factors that increase the risk of this transition [26].

The causal link between rapid gains in adiposity during infancy and risk of obesity is not clear. Cole has argued that this is a statistical phenomenon and not a physiological one, as individuals who are obese later in life are more likely to have a higher weight earlier in life and more likely to be crossing major weight centiles earlier in life [27]. Even if rapid gains in adiposity during infancy are not causally related to obesity risk, they may be useful clinical markers for predicting subsequent risk of obesity [10]; however, additional work is needed to confirm this as simple measures of childhood adiposity may not have strong predictive value for adult adiposity or disease risk [28].

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First, we used prospectively collected and longitudinal research-quality anthropometry measurements to characterize children’s BMI trajectories. In addition, we used BMI and BIA to define overweight and obesity status at age 8 years. However, our sample size was modest when examining the number of children who were obese or overweight at age 8 years. Despite this, we observed large and statistically significant, albeit imprecise, differences in mean BMI z-scores or rates of BMI z-score change when comparing children who were obese, overweight, or normal weightat age 8 years. Second, we used linear fixed effect models to characterize average BMI and rates of BMI change over the first 5 years of life according to age 8-year adiposity status. While prior studies have classified longitudinal measures of adiposity and related these to subsequent adiposity status, it was unlikely that our sample size was large enough to identify unique classes with sufficient sample size [29]. Indeed, prior studies using these methods with larger sample sizes (n > 1000) still observed relatively small cell sizes for some trajectories of adiposity (e.g., n < 20) [15]. Third, while we adjusted for several determinants of childhood obesity, we could not adjust for child diet or physical activity. In addition, our modest sample size precluded us from examining differences in subgroups of children; however, we did observe similar patterns of adiposity gain among children without in utero growth restriction or who were born at term. Fourth, we examined a group of healthy and typically developing US children. Still, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations if there are environmental or genetic factors that modify the relations between growth and risk of childhood obesity. Finally, we examined several features of early childhood growth and some of our results may be chance findings. However, these features were consistent when we used either BMI or BIA to define overweight/obesity status at age 8 years, thus reducing the possibility of spurious results.

Conclusions

Our results, from this modestly sized cohort, contribute to the body of literature suggesting that the risk of childhood obesity has origins in early in life. Efforts to identify interventions to prevent childhood obesity should focus on the periods of gestation and infancy as obesity risk may be malleable during these periods.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- HOME:

-

Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment

- IOTF:

-

International Obesity Task Force

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Collaboration NCDRF. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–14.

Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360(9331):473–82.

Brisbois TD, Farmer AP, McCargar LJ. Early markers of adult obesity: a review. Obesity Reviews. 2012;13(4):347–67.

Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KM. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(5):403–11.

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, Armstrong R, Prosser L, Summerbell CD. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews (Online). 2011;12:CD001871.

Williams SM, Goulding A. Early adiposity rebound is an important predictor of later obesity. Obesity. 2009;17(7):1310.

Ong KK, Loos RJ. Rapid infancy weight gain and subsequent obesity: systematic reviews and hopeful suggestions. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(8):904–8.

Ekelund U, Ong K, Linne Y, Neovius M, Brage S, Dunger DB, Wareham NJ, Rossner S. Upward weight percentile crossing in infancy and early childhood independently predicts fat mass in young adults: the Stockholm weight development study (SWEDES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):324–30.

Druet C, Stettler N, Sharp S, Simmons RK, Cooper C, Smith GD, Ekelund U, Levy-Marchal C, Jarvelin MR, Kuh D, et al. Prediction of childhood obesity by infancy weight gain: an individual-level meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(1):19–26.

Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Sherry B, Oken E, Haines J, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Crossing growth percentiles in infancy and risk of obesity in childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(11):993–8.

Glavin K, Roelants M, Strand BH, Juliusson PB, Lie KK, Helseth S, Hovengen R. Important periods of weight development in childhood: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:160.

Perng W, Hajj H, Belfort MB, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kramer MS, Gillman MW, Oken E. Early life weight gain, and Midchildhood Cardiometabolic health. J Pediatr. 2016;173:122–130 e121.

Sachdev HS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Lakshmy R, Dey Biswas SK, Leary SD, Reddy KS, Barker DJ, Bhargava SK. Anthropometric indicators of body composition in young adults: relation to size at birth and serial measurements of body mass index in childhood in the New Delhi birth cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(2):456–66.

Peneau S, Giudici KV, Gusto G, Goxe D, Lantieri O, Hercberg S, Rolland-Cachera MF. Growth trajectories of body mass index during childhood: associated factors and health outcome at adulthood. J Pediatr. 2017;186:64–71 e61

Giles LC, Whitrow MJ, Davies MJ, Davies CE, Rumbold AR, Moore VM. Growth trajectories in early childhood, their relationship with antenatal and postnatal factors, and development of obesity by age 9 years: results from an Australian birth cohort study. Int J Obesity (2005). 2015;39(7):1049–56.

Min J, Li J, Li Z, Wang Y. Impacts of infancy rapid weight gain on 5-year childhood overweight development vary by age and sex in China. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(5):365–373.

Braun JM, Lanphear BP, Calafat AM, Deria S, Khoury J, Howe CJ, Venners SA. Early-life bisphenol a exposure and child body mass index: a prospective cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(11):1239–45.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660–7.

WHO. WHO child growth standards: methods and development: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

McCarthy HD, Cole TJ, Fry T, Jebb SA, Prentice AM. Body fat reference curves for children. Int J Obesity (2005). 2006;30(4):598–602.

Boeke CE, Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Gillman MW. Correlations among adiposity measures in school-aged children. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:99.

Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:6.

Min J, Li J, Li Z, Wang Y. Impacts of infancy rapid weight gain on 5-year childhood overweight development vary by age and sex in China. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(5):365–73.

Kain J, Martinez M, Close M, Uauy R, Corvalan C. The association of excessive growth with development of general and central obesity at 7 years of age in every period after birth in Chilean children. Nutrition. 2016;32(4):426–31.

Cheung PC, Cunningham SA, Narayan KM, Kramer MR. Childhood obesity incidence in the United States: a systematic review. Child Obes. 2016;12(1):1–11.

Cole TJ. Children grow and horses race: is the adiposity rebound a critical period for later obesity? BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:6.

Simmonds M, Burch J, Llewellyn A, Griffiths C, Yang H, Owen C, Duffy S, Woolacott N. The use of measures of obesity in childhood for predicting obesity and the development of obesity-related diseases in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(43):1–336.

Jones B, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating Devleopmental trajectories. Sociol Method Res. 2001;29:374–93.

Acknowledgements

We thank the HOME Study staff for their efforts over the years and the participants for their dedication to the study.

Funding

This work was supported by NIEHS grants R01 ES025214 and R01 ES020349.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed for the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the investigators upon reasonable request. Detailed information about the HOME Study eligibility, recruitment, follow-up, and data- and bio-repository are provided in Braun et al., Int J. Epid, 2016. Individuals can contact the corresponding author for a data request form and these are evaluated by the study investigators. We have previously made data available to investigators submitting reasonable requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMB conceived the research question, carried out the statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. GDP provided critical support about the statistical modeling and reviewed the statistical analyses. HK provided feedback on anthropometry measurements. AC and BPL were responsible for initiating the cohort and overseeing follow-up through age 8 years. All authors were involved in the writing of the paper and approved the submitted and published versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review boards of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the cooperating delivery hospitals approved this study. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All parents or caregivers provided informed consent for their child to participate in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of mother-child pairs in the HOME Study according inclusion vs. exclusion status. Supplemental Table 2. Proportion of children who were overweight or obese at ages 4 weeks to 5 years according to World Health Organization definitionsa. Supplemental Table 3. Univariate Statistics of BMI Z-scores at each Study Visit According to Children’s Overweight/Obesity Status Assessed by WHO BMI z-score at Age 8 Yearsa. Supplemental Table 4. Univariate Statistics of BMI Z-scores at each Study Visit According to Children’s Overweight/Obesity Status Assessed by Bioelectric Impedance at Age 8 Yearsa. Supplemental Figure 1. Flowchart describing study participant selection in present study. (DOCX 79 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Braun, J.M., Kalkwarf, H.J., Papandonatos, G.D. et al. Patterns of early life body mass index and childhood overweight and obesity status at eight years of age. BMC Pediatr 18, 161 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1124-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1124-9