Abstract

Background

Diabetic macular edema (DME) causes severe vision loss among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). We aimed to investigate systemic and ocular diseases associated with the development of DME in a Japanese population.

Methods

A total of 3.11 million Japanese subjects who were registered in the database of the Japan Medical Data Center from 2005 to 2014 were analyzed. Subjects with DM were defined as individuals who had been prescribed any therapeutic medications for DM, and associated diseases were analyzed. The periods assessed were one year before the development of DME among patients with DME and one year before the last visit to an ophthalmic clinic among patients without DME.

Results

A total of 17,403 patients with DM satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 420 patients developed DME. Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between 55 diseases, including 39 systemic and 16 ocular diseases, and DME development. Logistic analysis identified 21 systemic diseases and 10 ocular diseases as significant factors associated with DME development.

Conclusion

Various types of systemic and ocular diseases are associated with DME development. Subjects with DM who present these risk factors must be carefully monitored to prevent visual impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) continues to increase worldwide, and diabetic retinopathy (DR) remains a leading cause of vision loss in many countries [1, 2]. The reported prevalence of DR among patients with DM varies widely, from 1 to 40% [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. According to Yau et al., approximately 93 million people worldwide develop DR, 17 million are diagnosed with proliferative DR (PDR), and 21 million are diagnosed with diabetic macular edema (DME) [10].

Although PDR is the most common vision-threatening retinopathy, DME is responsible for most of the vision loss experienced by patients with DM and remains the major cause of vision loss among patients with DM with or without PDR. Many previous population-based or hospital-based studies have focused on the prevalence of DME, yet there are few large-scale studies examining the incidence of DME. In addition, the annual incidence rates of DME in previous studies varied widely from 0.01 to 6.0% [11,12,13,14,15].

Previous epidemiological studies have also identified several risk factors associated with DR, including many systemic and lifestyle factors, nephropathy, obesity, alcohol consumption, hematological markers of anemia, hypothyroidism, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, hyperglycemia, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes duration, ethnic origin, pregnancy, and puberty [10, 16,17,18,19,20,21]. Some risk factors have been associated with DME development, including duration of diabetes, hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, nephropathy, higher cholesterol, retinal and vitreous inflammation, and oxidative stress in the retina [22], but inconsistencies exist among reports [23]. Furthermore, risk factors for DME may differ from those for DR, and the precise roles of these factors in the pathogenesis of DME are not well defined. Some epidemiological studies have examined the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for DM and DR, including studies employing the Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group (JDDM). Unfortunately, an insufficient number of studies have focused on DME in Japan. Currently, the main therapeutic procedures for DME are laser photocoagulation, vitrectomy, and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections, though these approaches are not always effective. In addition to the three approaches mentioned above, targeted therapies can ameliorate some of the identified risk factors. Here, we investigate systemic and ocular factors associated with DME development in a large-scale study based on the health insurance claim database in Japan.

Methods

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board (IRB) of the University of Yamanashi. The IRB approved this study without requiring written informed consent from any of the patients because no data used in this study contained any personal information.

Database

We used the health insurance claim database from the Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC), which contains medical data for patients using Employee Health Insurance, one of two major public insurance providers covering employees and their dependents. The JMDC was established in 2002 and is the largest medical database in Japan. The details of this database have been described elsewhere [24,25,26]. Briefly, the database records all individual medical claims from different hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies via a computer-aided postentry standardization method and an anonymous linkage system for patients using the same insurance provider. This database enables the aggregation of all claims for the same patient without duplicating medical claims.

The database includes data on age, sex, International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes, the ICD-10 corresponding standard disease name master codes (referred as ICD-10 standard disease code), prescribed drugs, medical examinations, treatment, and the medical institution size, if medical records are available.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study included subjects who were registered in the JMDC database between 2005 and 2014 and for whom medical records for more than one year were available. All registered data in the database were included in the analysis. Subjects listed with any of the ICD-10 categories from E11 to E14 were extracted as candidates with DM. Among these subjects, those with a history of being prescribed any anti-DM drug, either an oral or injectable drug, were included in the analysis. Subjects satisfying any of the following conditions were excluded from the analysis. Subjects who terminated their Employee Health Insurance and for whom the subsequent insurance provider was unable to be identified. Subjects for whom any of the aforementioned DM-related ICD-10 information was not confirmed in the final record during the investigated period. We excluded patients without DM who were diagnosed with central retinopathy, macular edema, maculopathy, or cystoid macular edema because some of these individuals may have had DM undiagnosed.

Definition of DME

Among subjects with DM, individuals with any of the following ICD10 subclassification disease names (ICD10 disease code) were categorized as having DME: diabetic maculopathy (E143), type 1 diabetic macula edema (E103), diabetic macula edema (E143), and type 2 diabetic maculopathy (E113).

Comparison of DME-associated risk factors

We investigated risk factors associated with DME development by comparing the following two groups: (1) a group of patients with DME and a one-year claim record before the development of DME and (2) a group of patients without a DME diagnosis throughout the investigated period. Because we were unable to collect data regarding medical examination results for risk factors proposed in previous studies, including laboratory data, biological information, and genetic data, we focused on ICD-10 standard disease codes to identify risk factors associated with DME.

The current study compared ICD-10 standard disease codes for one year before DME development in a group of patients with DME and those for the most recent year in a group of patients without DME.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analyses, the chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests were employed to compare demographics between the DME and DME-free groups.

According to suggestions from two experts in the field of medical statistics, Dr. Hiroshi Yokomichi and Dr. Tatsuhiko Saigo, we applied the criteria listed below to limit ICD-10 codes for a proper analysis of these codes associated with the development of DME because the total number of ICD-10 codes was 6345, which may hinder accurate analysis of factors associated with DME development.

As the first step, ICD-10 codes satisfying the following two conditions were excluded: the total number of patients with that code was less than 0.1% of all enrolled subjects, and fewer than five subjects were diagnosed with that ICD-10 standard disease code. The chi-square test was utilized to identify associated disease codes, and codes with a P value of less than 0.05 were selected as significantly associated risk factors for DME in univariate analysis. Codes categorized as significant risk factors in univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis in addition to age and sex as risk factors, and codes with a P value less than 0.05 were considered significantly associated risk factors.

Results

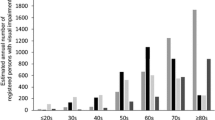

The total number of subjects registered in the database from 2005 to 2014 was 3,110,867. Of these, the total number of patients with DM was 66,923, with a mean age of 53.4 ± 11.0 years. Overall, 21,463 subjects had a DM-related ocular manifestation. After excluding subjects who did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, 17,403 individuals with a mean age of 55.7 ± 10.8 years were included in the analysis. Four hundred twenty subjects were diagnosed with DME, with a mean age of 55.2 ± 10.0 years, and the demographics of the enrolled subjects are listed in Table 1. DR was significantly more prevalent in males than females, but the incidence of DME development was not significantly different between males and females. Patients with and without DME visited medical institutions for diabetes treatment at frequencies of 3.2 times/year and 2.9 times/1 year, respectively, which was not a significant difference. The two groups also showed the same frequency of ophthalmological examinations (4.3 times/year). Among the 6345 ICD-10 standard disease codes, 86 were selected for investigating ICD-10 codes associated with the development of DME.

Systemic factors associated with DME development: multivariate analysis

Systemic risk factors associated with DME development are shown in Table 2. Femoral head fractures showed the highest odds ratio (OROR, 7.04), followed by hyperlipidemia (OR 6.67) and impending abortion (OR 6.14). In contrast, four factors, chronic eczema (OR 0.12), ureterolithiasis (OR 0.13), hay fever (OR 0.13) and osteoarthritis of the knee (OR 0.55), were identified as factors that were negatively associated with DME development (Table 3).

Ocular factors associated with DME development: multivariate analysis

Ten ocular risk factors associated with DME development were revealed (Table 4). Retinal vessel occlusion had the highest risk (OR 8.28), followed by eye movement disorder (OR 5.99). Intraocular lens insertion and posterior vitreous detachment were identified as significant factors in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis. No ICD-10 codes were identified as ocular factors having an inverse correlation with DME development.

The results of univariate analysis for systemic and ocular factors associated with DME are summarized in Supplemental Tables 1 to 4.

Discussion

Although the global incidence of DM is increasing, that of DR is reported to be decreasing [27]. This finding might be explained by improvements in the control of systemic risk factors in patients with DM. DM-related severe ocular complications are one of the main causes of blindness worldwide. According to a recent study, DME is causing an increasing number of visual impairments in patients with DM [22]. DME, which does not result in total blindness but in severe vision loss, may instead be the main DM-associated severe ocular complication. In addition, advances in optical coherence tomography technology have enabled the identification of DME much more precisely and less invasively than before. Some previous studies have investigated factors associated with DME. However, many of these studies employed a cross-sectional design [8, 22, 23, 28,29,30,31]. Although several studies have investigated factors associated with DME development, [2, 14, 32,33,34,35] associations between concomitant and systemic diseases with DME were not reported. In the present study, we investigated factors associated with DME development among more than 6000 ICD-10 standard disease codes using a large claim dataset in Japan. Many of the systemic factors significantly associated with the development of DME are considered to be related to the presence of severe metabolic impairment, including hyperlipidemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, vessel lumen mass, postoperative percutaneous coronary angioplasty, lower leg skin ulcer, arrhythmia, diabetic nephropathy, and proteinuria. Impairment of microvasculature in the retina results in breakdown of the retinal pigment epithelial barrier, which is one of the key steps in DME development. Many systemic factors, including hyperglycemia, inflammation, and vascular endothelial dysfunction, are associated with DM-related microvasculature damage. Accordingly, there is a clear relationship between systemic microvasculature damage and ocular complications. Yamamoto et al. reported that diabetes, proteinuria and glomerular filtration rate were associated with higher risks of diabetic eye diseases, including DME [36].

DM has been identified as an important risk factor for osteoporosis-associated fracture [37, 38]. Among female subjects with type 1 DM, diabetic ketoacidosis in pregnancy can result in impending abortion. Because DM sometimes results in peripheral vestibular damage and predicts a poor prognosis of typical vestibular pathologies, some patients develop benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, which is one symptom of Ménière syndrome. Poor visual function due to DME may contribute to increased risk of falls, resulting in cervical and chest contusions. Furthermore, female patients with DM are more likely to report very irregular menstrual cycles [39]. Although the present study identified arthritis as a risk factor for developing DME, Tentolouris et al. found a negative correlation between arthritis and DM [40]. Regardless, the impact of DM on the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis is not well established.

The present study also revealed some systemic factors that were negatively associated with the development of DME. Some previous studies reported a significantly higher prevalence of primary osteoarthritis among subjects with DM than among those without DM, as well as significant associations with glycemic control and the duration of diabetes. Obesity may be associated with the onset of osteoarthritis, [41,42,43] though we are unsure why our study showed a negative impact of osteoarthritis on DME. According to Taylor et al., diabetes may increase the risk of kidney stone formation by altering the composition of the urine, and insulin resistance may play a role in stone formation [44].

Moreover, several systemic diseases and ocular diseases that have not been reported to be related to DME development were identified. Interestingly, some factors were identified as negative factors. An explanation for the finding that hay fever and chronic eczema were significantly and negatively associated with DME development may be impairment of autoimmune function, as DM deteriorates autoimmune function, and a significantly lower prevalence of allergic rhinitis has been observed in subjects with metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure, or impaired fasting glucose levels [45].

Many previous studies have focused on the effects of DM on pathological conditions and disorders, whereas few have investigated factors associated with the development of DME in a large sample. We were unable to precisely investigate the status of glycemic control and severity of DM complications in the present study, and further studies are thus necessary to clarify these points.Although some significantly associated systemic factors identified in the current study are consistent with previous reports, some of them have never been reported to be associated with the development of DME. In addition to diseases found to act as risk factors to date, such as renal and circulatory disorders, orthopedic and dermatological diseases were identified to be associated with the development of DME, which may be because the current study included more than 6000 diseases in the analysis. Furthermore, some factors were found to be negatively associated with DME. Currently, information about the mechanisms of these factors in DME development is limited, and these data must be confirmed in further investigations.

Previous papers have reported some ocular factors associated with DME development, including DR severity, [2, 32, 46] cataract surgery, [33] and ocular inflammation, [35] consistent with the current results. The present study also revealed some new ocular factors associated with DME development, some of which are related to systemic and ocular DM complications. As possible explanations for these associations, ocular movement disorder and accommodative paralysis or corneal disease and ocular pain may be related to microvasculature destruction or DM-associated loss of tear-film stability, respectively. Additionally, scleritis and conjunctivitis may be related to DM-induced microinflammation. Retinal vessel occlusion showed the highest OR and was selected as a disease often observed in subjects with retinal circulation disorders and severe diabetic retinopathy. Moreover, eye movement disorder and accommodation paralysis are strongly associated with DME development. Further studies are necessary to clarify the mechanism between DME and systemic or ocular risk factors.

This study also has several limitations. Because the subjects were limited to social insurance subscribers and because subscribers of national health insurance, another major insurance provider in Japan, was not considered, the target sample may be biased. National health insurance is managed by each municipality, increasing the difficulty of integrating and collecting data; hence, these data were not included in the study. As subjects in JMDC constitute employees and their dependents, it is possible that a significant number of senior citizens, whose prevalence of DM could be higher than that in JMDC, were not included in the database. National health insurance members must also be considered in the future. The use of diagnosis codes of claims data as diagnostic criteria also has several problems. First, the accuracy of the diagnosis is not necessarily high. The currently used database may include subjects who have not been medically diagnosed with DM to obtain reimbursement from health insurance. Therefore, only patients who were prescribed anti-DM drugs were included in this study. An investigation of whether some reported risk factors are associated with DME development was impossible because the current database does not contain information about certain factors, including hemoglobin A1c levels [14] and the severity of DR [2, 32, 46]. Genetic factors have also been reported to contribute to DME development, such as genes related to VEGF and erythropoietin [47,48,49,50,51]. Unfortunately, claims data do not contain genetic information. In this study, we worked with epidemiological statisticians to accurately detect risk factors associated with DME development from many disease categories, but it was difficult to completely exclude the influence of confounding factors. Because no accurate information regarding the type of DM was available for approximately half of all subjects, it was impossible to compare risk factors between type 1 DME and type 2 DME. We excluded some diseases due to a small number of patients, which may have involved factors for which we could not detect an association. Inconsistencies between previous reports and the current study may also be partially due to differences in the statistical methods applied. Previous studies have reported differences between DR- and DME-associated factors. In this study, we focused on factors associated with the development of DME. In the future, it will be necessary to examine factors associated with the development of DMR and DME using the same database.

Conclusions

In this study, we clarified systemic and ocular diseases associated with DME development in Japan. Notably, many patients with DM do not undergo periodic eye examinations. Based on the results, factors associated with DME development should be closely monitored. Because DR is may be asymptomatic during the period in which laser photocoagulation should be applied, asymptomatic individuals should be screened to minimize the risk of vision loss. As the number of DME patients is expected to increase, further studies on the early detection and prevention of DME development are needed.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the JMDC, but restrictions apply with regard to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and thus are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the JMDC.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

Diabetic mellitus

- DME:

-

Diabetic macular edema

- DR:

-

Diabetic retinopathy

- PDR:

-

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases 10th revision

- JMDC:

-

Japan Medical Data Center

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Congdon NG, Friedman DS, Lietman T. Important causes of visual impairment in the world today. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2057–60..

Mohamed Q, Gillies MC, Wong TY. Management of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298(8):902–16.

Klein R, Klein BK, Moss SE, Davis MD, DeMets DL. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy: ii. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(4):520–6.

Leske MC, Wu S-Y, Hyman L, Li X, Hennis A, Connell AMS, Schachat AP. Diabetic retinopathy in a black population: the Barbados eye study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(10):1893–9.

Mitchell P, Smith W, Wang JJ, Attebo K. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in an older community: the blue mountains eye study. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(3):406–11.

West SK, Klein R, Rodriguez J, Muñoz B, Broman AT, Sanchez R, Snyder R. Diabetes and diabetic retinopathy in a Mexican-American population. Proyecto VER. 2001;24(7):1204–9.

Hamman RF, Mayer EJ, Moo-Young GA, Hildebrandt W, Marshall JA, Baxter J. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics with NIDDM: San Luis Valley diabetes study. Diabetes. 1989;38(10):1231–7.

Ding J, Wong TY. Current epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(4):346–54.

Kempen JH, O'Colmain BJ, Leske MC, Haffner SM, Klein R, Moss SE, Taylor HR, Hamman RF. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):552–63.

Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, Chen S-J, Dekker JM, Fletcher A, Grauslund J, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556–64.

Salinero-Fort MA, San Andres-Rebollo FJ, de Burgos-Lunar C, Arrieta-Blanco FJ, Gomez-Campelo P. Four-year incidence of diabetic retinopathy in a Spanish cohort: the MADIABETES study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76417.

Jones CD, Greenwood RH, Misra A, Bachmann MO. Incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy during 17 years of a population-based screening program in England. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):592–6.

Younis N, Broadbent DM, Vora JP, Harding SP. Incidence of sight-threatening retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes in the Liverpool diabetic eye study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361(9353):195–200.

Romero-Aroca P, Baget-Bernaldiz M, Navarro-Gil R, Moreno-Ribas A, Valls-Mateu A, Sagarra-Alamo R, Barrot-De La Puente JF, Mundet-Tuduri X. Glomerular Filtration Rate and/or Ratio of Urine Albumin to Creatinine as Markers for Diabetic Retinopathy: A Ten-Year Follow-Up Study. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:5637130.

Martin-Merino E, Fortuny J, Rivero-Ferrer E, Garcia-Rodriguez LA. Incidence of retinal complications in a cohort of newly diagnosed diabetic patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100283.

Cheung N, Wong TY. Obesity and eye diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(2):180–95.

Wang S, Wang JJ, Wong TY. Alcohol and eye diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(5):512–25.

Sasaki M, Kawashima M, Kawasaki R, Uchida A, Koto T, Shinoda H, Tsubota K, Wang JJ, Ozawa Y. Association of Serum Lipids with Macular Thickness and Volume in type 2 diabetes without diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(3):1749–53.

Conway BN, Miller RG, Klein R, Orchard TJ. Prediction of proliferative diabetic retinopathy with hemoglobin level. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(11):1494–9.

Yang J-K, Liu W, Shi J, Li Y-B. An association between subclinical hypothyroidism and sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1018–20.

Klein BK, Knudtson MD, Tsai MY, Klein R. The relation of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction to the prevalence and progression of diabetic retinopathy: Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1175–82.

Lee R, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss. Eye Vis (Lond). 2015;2:17.

Liu E, Craig JE, Burdon K. Diabetic macular oedema: clinical risk factors and emerging genetic influences. Clin Exp Optom. 2017;100(6):569–76.

Kume A, Ohshiro T, Sakurada Y, Kikushima W, Yoneyama S, Kashiwagi K. Treatment patterns and health care costs for age-related macular degeneration in Japan: an analysis of National Insurance Claims Data. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1263–8.

Kimura S, Sato T, Ikeda S, Noda M, Nakayama T. Development of a database of health insurance claims: standardization of disease classifications and anonymous record linkage. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(5):413–9.

Kashiwagi K, Furuya T. Persistence with topical glaucoma therapy among newly diagnosed Japanese patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2014;58(1):68–74.

Sloan FA, Belsky D, Ruiz D Jr, Lee P. Changes in incidence of diabetes mellitus–related eye disease among us elderly persons, 1994-2005. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(11):1548–53.

Diep TM, Tsui I. Risk factors associated with diabetic macular edema. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(3):298–305.

Varma R, Bressler NM, Doan QV, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(11):1334–40.

Kayýkçýolu Ö, Özmen B, Seymenoglu G, Tunalı D, Kafesçiler SÖ, Güclü F, Hekimsoy Z. Macular edema in unregulated type 2 diabetic patients following glycemic control. Arch Med Res. 2007;38(4):398–402.

Acan D, Calan M, Er D, Arkan T, Kocak N, Bayraktar F, Kaynak S. The prevalence and systemic risk factors of diabetic macular edema: a cross-sectional study from Turkey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18(1):91.

Klein R, Knudtson MD, Lee KE, Gangnon R, Klein BE. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy XXIII: the twenty-five-year incidence of macular edema in persons with type 1 diabetes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):497–503.

Loewenstein A, Zur D. Postsurgical cystoid macular edema. Dev Ophthalmol. 2010;47:148–59.

Kim SJ, Equi R, Bressler NM. Analysis of macular edema after cataract surgery in patients with diabetes using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(5):881–9.

Tang J, Kern TS. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30(5):343–58.

Yamamoto M, Fujihara K, Ishizawa M, Osawa T, Kaneko M, Ishiguro H, Matsubayashi Y, Seida H, Yamanaka N, Tanaka S, et al. Overt proteinuria, moderately reduced eGFR and their combination are predictive of severe diabetic retinopathy or diabetic macular edema in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(7):2685–9.

Janghorbani M, Feskanich D, Willett WC, Hu F. Prospective study of diabetes and risk of hip fracture: the Nurses' health study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1573–8.

Lipscombe LL, Jamal SA, Booth GL, Hawker GA. The risk of hip fractures in older individuals with diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):835–41.

Cawood EH, Bancroft J, Steel JM. Perimenstrual symptoms in women with diabetes mellitus and the relationship to diabetic control. Diabet Med. 1993;10(5):444–8.

Tentolouris A, Thanopoulou A, Tentolouris N, Eleftheriadou I, Voulgari C, Andrianakos A, Sfikakis PP. Low prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis among patients with pre-existing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(20):399.

Neumann J, Hofmann FC, Heilmeier U, Ashmeik W, Tang K, Gersing AS, Schwaiger BJ, Nevitt MC, Joseph GB, Lane NE, et al. Type 2 diabetes patients have accelerated cartilage matrix degeneration compared to diabetes free controls: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(6):751–61.

Arellano Perez Vertti RD, Aguilar Muniz LS, Moran Martinez J, Gonzalez Galarza FF, Arguello Astorga R. Cartilage Oligomeric matrix protein levels in type 2 diabetes associated with primary knee osteoarthritis patients. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2019;23(1):16–22.

Dubey NK, Ningrum DNA, Dubey R, Deng YH, Li YC, Wang PD, Wang JR, Syed-Abdul S, Deng WP. Correlation between Diabetes Mellitus and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Dry-To-Wet Lab Approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3021.

Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2005;68(3):1230–5.

Hwang IC, Lee YJ, Ahn HY, Lee SM. Association between allergic rhinitis and metabolic conditions: a nationwide survey in Korea. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016;12:5.

Browning DJ, Fraser CM, Clark S. The relationship of macular thickness to clinically graded diabetic retinopathy severity in eyes without clinically detected diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(3):533–9 e532.

Graham PS, Kaidonis G, Abhary S, Gillies MC, Daniell M, Essex RW, Chang JH, Lake SR, Pal B, Jenkins AJ, et al. Genome-wide association studies for diabetic macular edema and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):71.

Awata T, Kurihara S, Takata N, Neda T, Iizuka H, Ohkubo T, Osaki M, Watanabe M, Nakashima Y, Inukai K, et al. Functional VEGF C-634G polymorphism is associated with development of diabetic macular edema and correlated with macular retinal thickness in type 2 diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333(3):679–85.

El-Shazly SF, El-Bradey MH, Tameesh MK. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphism prevalence in patients with diabetic macular oedema and its correlation with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment outcomes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42(4):369–78.

Kaidonis G, Burdon KP, Gillies MC, Abhary S, Essex RW, Chang JH, Pal B, Pefkianaki M, Daniell M, Lake S, et al. Common sequence variation in the VEGFC gene is associated with diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(9):1828–36.

Abhary S, Burdon KP, Casson RJ, Goggin M, Petrovsky NP, Craig JE. Association between erythropoietin gene polymorphisms and diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):102–6.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the kind cooperation of Ms. Makiko Kaneko and Ms. Rie Nishikino in providing and analyzing the data. This study was performed with the assistance of the JMDC. Tatsuhiko Saigo provided assistance as a medical statistician. We thank Tomohiro Ohshiro and Youichi Sakurada for commenting on this study as experts in the field.

Funding

This study did not receive any funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK contributed to the design and analysis of the study and to writing the paper. AK contributed to collecting and analyzing the data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Yamanashi Ethical Review Board. Because the data used in this study do not contain any personal information, the Ethical Review Board agreed to allow this study to proceed without requiring written informed consent from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

None of the authors have conflicts of interest with the information presented in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1

Systemic risk factors associated with DME development: univariate analysis. (ICD10; International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, DME; diabetic macular edema, CI; confidence interval).

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2

Systemic factors that suppressed DME development: univariate analysis. (ICD10; International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, DME; diabetic macular edema, CI; confidence interval).

Additional file 3: Supplemental Table 3

Ocular risk factors associated with DME development: univariate analysis. (ICD10; International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, DME; diabetic macular edema, CI; confidence interval).

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table 4

Ocular factors that suppressed DME development: univariate analysis. (ICD10; International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, DME; diabetic macular edema, CI; confidence interval).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kume, A., Kashiwagi, K. Systemic and ocular diseases associated with the development of diabetic macular edema among Japanese patients with diabetes mellitus. BMC Ophthalmol 20, 309 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01578-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01578-8