Abstract

Background

DNA is an important target for oxidative attack and its modification may increase the risk of mutagenesis. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare salivary levels of the oxidative stress biomarker 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in patients with oral cancer (OC) compared to the control group by a comprehensive search of the available literature.

Methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and was registered in Open Science Framework (OSF): https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/X3YMR. Four electronic databases were used to identify studies for this systematic review: PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science from January 15, 2005, to April 15, 2021. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool was used to assess article quality.

Results

Of the 166 articles identified, 130 articles were excluded on the basis of title and abstract screening (duplicates, reviews, etc.). Thirty-six articles were evaluated at full text and 7 articles met the inclusion criteria. Of these, only 5 studies had compatible data for quantitative analysis. An increase in salivary 8-OHdG levels was found in patients with OC compared to healthy subjects, but without statistical significance. 8-OHdG: SMD = 2,72 (95%CI= -0.25–5.70); *p = 0.07.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests a clear trend of increased 8-OHdG levels in saliva of OC patients compared to the control group. However, further studies are required to clarify and understand the altered levels of this oxidative stress marker.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Oral cancer (OC) is a malignant neoplasm that in ≈ 90% of cases, histologically corresponds to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [1], which can arise de novo or from oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMD) such as oral erythroplasia, oral submucosal fibrosis and/or oral leukoplakia [2] OSCC represents the 16th most common cancer worldwide, with more than 377,000 new cases per year [3]. The 5-year survival rate is 50% and decreases to 30% as the stage of the disease advances [4], making it a major social, economic and public health problem [5]. Tobacco and alcohol are the main etiological factors contributing to its development [6]. OSCC most frequently affects men in the 5th to 6th decade of life [7]. Clinically, the lesions present as asymptomatic, nonhealing ulcers of variable size and indurated borders [8]. These lesions are usually found on the tongue, floor of the mouth, buccal mucosa, alveolar ridges, retromolar trigone and hard palate [9]. The diagnosis is made by a thorough, visual and clinical examination of the oral cavity and confirmed by histopathological study of surgical biopsy as part of the gold standard [10].

Currently, clinicians and researchers in the field have made several efforts to find molecules indicative of the onset and progression or transformation of OPMD to OSCC [11]. In this regard, saliva is a biofluid that, unlike others, is more accessible, cost-effective, simple to collect, and noninvasive [12]. Moreover, it reflects the oxidative status of subjects with this type of lesions [13].

Oxidative stress is an important process in the pathobiology of OSCC [14]. High concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) unbalance the antioxidant protection mechanisms provided by enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, reduced glutathione, superoxide dismutase and malondialdehyde [15].

The production of oxygen free radicals such as hydroxyl radicals (HO•) can cause significant damage to DNA strands. Interactions occurring between these molecules, and in particular on the nitrogenous base guanine form C8-hydroguanine (8-OHGua) and by electron abstraction mechanisms, 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is formed [16].

Some research has been published reporting differences in salivary levels of 8-OHdG and its possible association as a marker of DNA damage in patients with OC compared to the healthy population [17,18,19,20,21,22,23], however, to date, no systematic review summarizing those findings has been published.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate and compare the salivary levels of the oxidative stress biomarker 8-OHdG in OC patients compared to the healthy control group by a comprehensive search of the available literature.

Methods

Protocol and register

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were used to construct the protocol for the present systematic review and meta-analysis [24]. The Open Science Framework (OSF: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/X3YMR) platform was used to register the study.

PICOD and research question

-

1.

Population: Patients with OC.

-

2.

Intervention: Quantification of the analyte 8-OHdG in saliva of OC patients and systemically healthy patients.

-

3.

Comparators: Systemically healthy subjects.

-

4.

Outcomes: Observed changes in salivary 8-OHdG levels in OC patients and systemically healthy subjects.

-

5.

Design: Case-control studies.

The research question was: Are there significant differences between salivary 8-OHdG levels in patients with OC compared to the control group?

Elegibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Case-control studies.

-

Studies approved by the institutional ethics committee.

-

Studies that will confirm the diagnosis of OSCC by biopsy.

-

Stimulated/unstimulated saliva samples.

-

Techniques such as Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA) and DNA damage assay.

-

Investigations that will show numerical values (mean ± standard deviation) of 8-OHdG levels.

Exclusion criteria

-

Investigations in cell lines or animal models.

-

Case reports and case series.

-

Book chapters and encyclopedias.

-

Systematic, narrative, scoping, bibliometric reviews and meta-analyses.

-

Healthy controls with comorbidities and other systemic disorders.

-

Research published in a language other than English.

-

Research published before 2005.

Electronic and manual literature search

An electronic search was carried out in four databases: PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect and Web of Science from January 15, 2005, to April 15, 2021. For PubMed, the following search strategy was employed: (((“8-Hydroxy-2’-Deoxyguanosine”[Mesh]) AND “Saliva”[Mesh]) AND) AND “Mouth Neoplasms”[Majr]. For the rest, the keywords “8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine”, “8-OHdG”, “Saliva”, “Biomarkers” and “Oral Cancer” were used, along with the use of Boolean operators “OR” and “AND”. A manual search was also carried out in the following Journals: “Medicina Oral Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal”, “Oral Diseases” “Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology” and “Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine”.

Screening process

M.A.A.S and A.H screened study titles and abstracts independently. Duplicates and research unrelated to the topic of interest were then discarded. Finally, a full-text analysis of potentially eligible articles was performed by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

M.A.A.S and L.S.E.V performed the data collection procedure independently, in predefined tables with Word software (Microsoft):

-

Name of first author and year of publication.

-

Country of origin.

-

Gender.

-

Age.

-

Number of cases and controls.

-

Habits; alcoholism and smoking.

-

Techniques for detection of the analyte of interest.

-

Mean value ± standard deviation of salivary 8-OHdG levels.

-

p value.

Quantitative variables were represented with mean ± standard deviation, while qualitative data with absolute and relative frequency n (%).

Quality assessment

M.A.A.S and A.H assessed the quality of the included studies independently. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool [25] was used. The items taken into account were aspects related to comparability, exposure, confounders, time, and statistical analysis of cases and controls. In the study, quality was assessment on a scale ranging from 0 to 100%. Studies scoring between of 0–49% was categorized as low quality, those scoring between 50% and 69% moderate quality, and studies scoring above 70% were categorized as high quality. Any discrepancies were resolved through group discussion.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative analysis on 8-OHdG levels assessed in ng/ml, between the OC patients group vs. control group, was performed using STATA 15 V software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The standardized mean difference (SMD) method with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used. A random effects model was used due to the presence of heterogeneity (> 50%=moderate), which was estimated using the Cochrane Q test and quantified with the (I2) statistic. A p* value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A forest plot was constructed to visualize estimates with 95% CI. Funnel plot and Egger linear regression were used to assess publication bias.

Results

Study selection

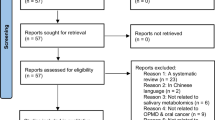

Initially 165 articles were found in the four electronic databases, including PubMed (n = 4 papers), Scopus (n = 4 papers), ScienceDirect (n = 156 papers) and Web of Science (n = 1 paper). In the manual search, one more article was found, giving a total of 166 articles. In the identification phase, duplicates were eliminated (n = 10). Next, based on title and abstract, 156 remaining studies were reviewed. Applying the eligibility criteria, 120 more records were excluded (reviews n = 66; encyclopedias n = 4; book chapters n = 32; others n = 18), giving a total of 36 potentially relevant records. After analyzing the full text of the remaining articles, 29 articles were excluded because they were not related to the topic of interest. Therefore, a total of 7 articles were included for qualitative analysis and of those, 5 articles were analyzed quantitatively in the present review. Details of the study selection are shown in Fig. 1.

Clinical and demographic features of studies included

A total of 7 articles with a case-control design were reviewed in this study [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. The total number of individuals studied in the included investigations was 664 of which 351 represented the case group (patients with OC) and 313 represented the control group (healthy subjects). The ages of the patients ranged from 30 to 82 years, with a mean age ± (SD) of 58 ± 7.04 years, of which 44% were male, 34% were female and the rest (22%) did not specify gender [22]. 41% of patients were smokers [17,18,19, 22, 23], while 24% were alcohol drinkers [17,18,19, 22]. Most of the articles were published after 2012 (6:86%) [17,18,19,20,21,22]. The oldest study was from 2006 [23], and the most recent from 2021 [17]. The seven studies were published in six different countries [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Two (29%) studies were conducted in India [18, 22], the rest (14.2%) were conducted in Korea [17], Poland [19], Belgium [20], Iran [21], and Israel [23]. The names of the journals where the articles were published are also described (Table 1).

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) emerged as the predominant immunodetection method for quantifying salivary 8-OHdG levels in OC patients (86%) [17,18,19,20,21, 23], followed by the DNA damage quantification kit (BioVision, USA) (14%) [22]. In addition, qualitative analysis revealed that there is an increase in salivary 8-OHdG levels in patients with OC compared to the control group [18, 20,21,22,23] (Table 2).

JBI assessment for case-controls studies

Based on the score obtained, 57% of the studies [17,18,19,20] showed high quality, while 43% showed moderate quality [21,22,23] (Table 3).

Meta-analysis: comparison of salivary 8-OHdG levels in oral cancer patients and control group

As shown in Fig. 2, five articles [17,18,19,20, 22] compared the difference between salivary 8-OHdG levels in OC patients (n = 300) and healthy controls (n = 258). An increase in salivary 8-OHdG levels was found compared to the healthy population (SMD = 2.72 (95%CI= -0.25–5.70); p = 0.07), but without statistical significance. Study heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 64.2%, *p = 0.025), therefore, a random-effects model was used to pool the results. The funnel plot samples the asymmetry and possibility of publication bias. Egger’s test (t = 2.10, p = 0.127) showed no evidence of bias (Fig. 2 panel A and B).

Discussion

OC is a multifactorial disease that arises through a complex sequence of events marked by diverse genetic and epigenetic modifications [26, 27]. One key underlying mechanism in its development and progression is oxidative stress, its role has been characterized by increased pro-oxidant activity, with a consequent decrease in antioxidant activity [28]. Thus, due to high metabolic activity and loss of mitochondrial function, tumor cells generate more ROS than normal cells, which increases susceptibility to free radicals and indeed oxidative stress [29]. Despite its significance in the pathogenesis of oral cancer, the clinical assessment of oxidative stress in this context has been limited.

To date, the expression of the oxidative stress marker 8-OHdG, which is formed from the oxidation of damaged DNA guanine, has only been assessed in plasma samples OSCC tissue biopsies and saliva (Fig. 3). In plasma 8-OHdG levels have been found to be lower in subjects with OPMD compared to healthy controls [30]. On the other hand, it has been reported that 80% of samples of OSSC tissue (24/30) showed strong immunostaining intensity, preferentially in the cytoplasm (70%) and nucleus (30%) of neoplastic cells. In addition, tumors exceeding 4 cm in size more frequently expressed 8-OHdG in the cytoplasm. Thus, greater oxidative damage occurs when both subcellular localization structures express 8-OHdG [31]. In saliva 8-OHdG detection has emerged as a promising tool for assessing oxidative burden and its relationship with oral cancer risk and progression. Saliva is a biofluid that is composed of a rich source of biomolecules (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and DNA) [32]. Its collection is relatively simple, inexpensive, reproducible and does not require much time with the patient [33]. Therefore, it can be used in large-scale studies to search for biomarkers capable of discriminating between healthy and diseased subjects [34]. At present, scientists have conducted many studies and more than 100 potential biomarkers have been reported until 2024 [35]. The use of validated salivary biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity can be used as a valuable tool for both screening and early detection of OSCC, which will increase the quality of medical care [36, 37].

In this systematic review, 7 case-control articles were included for the analysis of 8-OHdG in saliva of 351 OC patients and 313 healthy volunteers. The meta-analysis revealed that there is an increase in salivary 8-OHdG levels in the exposure group compared to the control group, but without statistical significance (p = > 0.05). Of the previously evaluated studies, two of them [17, 19] found no significant association of DNA damage marker 8-OHdG and OC. While five of them [18, 20,21,22,23], showed that salivary 8-OHdG levels were increased in patients with OC compared to the control group, reflecting the redox imbalance in these patients.

Nandakumar et al., 2020 [18] found that mean salivary 8-OHdG values increased progressively from healthy controls to subjects with oral submucous fibrosis and patients with OSCC. This gradient increase in 8-OHdG reflects the increased DNA damage and oxidative stress environment under these conditions. In this study also, smoking was positively correlated with salivary 8-OHdG levels in patients with OSCC. Whereas, betel chewing habit was positively correlated with salivary 8-OHdG levels in patients with oral submucous fibrosis, thus these habits along with alcohol consumption act synergistically and further aggravate the disease process [36, 38, 39]. Kaur et al., 2016 [20] demonstrated in their study that patients with PML and OC showed significantly higher levels of 8-OHdG and malondialdehyde, and lower levels of vitamin E and C compared to the healthy population. These findings are also consistent with that reported with Hosseini et al., 2012 [21] whereby, patients with PML such as oral leukoplakia, lichen planus and oral submucous fibrosis and OSCC are more susceptible to an imbalance of antioxidant-oxidative stress status [21]. Likewise, Kumar et al., 2012 [22] reported in their study an alteration of this system and observed a substantial increase in the levels of ROS, reactive nitrogen species and 8-OHdG in saliva cell DNA, along with a decrease in the levels of total antioxidant capacity and glutathione. These results are similar to those reported by Bahar et al., 2006 [23] who showed that oxidative and nitrative stress altered salivary composition in OC patients. Nitrates and nitrites increased substantially, while antioxidant enzymes were reduced, thus explaining the oxidative DNA and protein damage, possibly due to the promotion of OC.

Limitations

The present review had some limitations. On the one hand, the inclusion of a limited number of case-control studies, with a small sample size, as well as a moderate heterogeneity of the results obtained, which could be explained by the use of different clinical staging systems to classify patients with OSCC, two different methodologies to quantify salivary 8-OHdG levels, age, gender, ethnicity and geographic location, as well as other confounding factors such as smoking and alcohol intake could be altering the values of this marker. Future studies should consider these aspects to analyze the effect of oxidative stress on OC.

Conclusions

The present systematic review with subsequent meta-analysis revealed that the concentration of 8-OHdG in saliva of OC patients was 2,72ng/mL higher than that of healthy individuals, but without statistical significance p = 0.07. This trend toward greater decay reflects an increase in oxygen free radical activity during carcinogenesis in OC. However, further studies are required to clarify and confirm these results.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 8:

-

OHdG-8-hidroxi-2’-desoxiguanosina

- OSCC:

-

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- PML:

-

Potentially malignant lesions

- 8:

-

OHGua-C8-hidroguanina

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

References

Bugshan A, Farooq I. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: metastasis, potentially associated malignant disorders, etiology and recent advancements in diagnosis. F1000Res. 2020;9:229. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.22941.1.

Bastías D, Maturana A, Marín C, Martínez R, Niklander SE. Salivary biomarkers for oral Cancer detection: an exploratory systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:2634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052634.

Muller S, Tilakaratne WM. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck tumors: Tumours of the oral cavity and Mobile Tongue. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;16:54–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01402-9.

Almangush A, Mäkitie AA, Triantafyllou A, de Bree R, Strojan P, Rinaldo A, et al. Staging and grading of oral squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Oral Oncol. 2020;107:104799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104799.

Warnakulasuriya S, Kerr AR. Oral Cancer screening: past, Present, and Future. J Dent Res. 2021;100:1313–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345211014795.

Chamoli A, Gosavi AS, Shirwadkar UP, Wangdale KV, Behera SK, Kurrey NK et al. Overview of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Risk factors, mechanisms, and diagnostics. Oral Oncol. 2021;121:105451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105451.

Rivera C. Essentials of oral cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:11884–94.

Bagan J, Sarrion G, Jimenez Y. Oral cancer: clinical features. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:414–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.03.009.

Warnakulasuriya S. Clinical features and presentation of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125:582–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2018.03.011.

Lousada-Fernandez F, Rapado-Gonzalez O, Lopez-Cedrun JL, Lopez-Lopez R, Muinelo-Romay L, Suarez-Cunqueiro MM. Liquid biopsy in oral Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1704. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19061704.

Barros O, D’Agostino VG, Lara Santos L, Vitorino R, Ferreira R. Shaping the future of oral cancer diagnosis: advances in salivary proteomics. Expert Rev Proteom. 2024;2:149–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789450.2024.2343585.

Khurshid Z, Zafar MS, Khan RS, Najeeb S, Slowey PD, Rehman IU. Role of salivary biomarkers in oral Cancer detection. Adv Clin Chem. 2018;86:23–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acc.2018.05.002.

Zhou Q, Ye F, Zhou Y. Oxidative stress-related biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomark Med. 2023;17:337–47. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2022-0846.

Katakwar P, Metgud R, Naik S, Mittal R. Oxidative stress marker in oral cancer: a review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12:438–46. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.151935.

Ferraguti G, Terracina S, Petrella C, Greco A, Minni A, Lucarelli M, et al. Alcohol and Head and Neck Cancer: updates on the role of oxidative stress, genetic, epigenetics, oral microbiota, antioxidants, and Alkylating agents. Antioxid (Basel). 2022;11:145. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11010145.

Martin KR, Barrett JC. Reactive oxygen species as double-edged swords in cellular processes: low-dose cell signaling versus high-dose toxicity. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2002;21:71–5. https://doi.org/10.1191/0960327102ht213oa.

Shin YJ, Vu H, Lee JH, Kim HD. Diagnostic and prognostic ability of salivary MMP-9 for oral squamous cell carcinoma: a pre-/post-surgery case and matched control study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0248167. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248167.

Nandakumar A, Nataraj P, James A, Krishnan R. Estimation of salivary 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a potential biomarker in assessing progression towards malignancy: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21:2325–9. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.8.2325.

Babiuch K, Bednarczyk A, Gawlik K, Pawlica-Gosiewska D, Kęsek B, Darczuk D, et al. Evaluation of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant status and biomarkers of oxidative stress in saliva of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma and oral leukoplakia: a pilot study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2019;77:408–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016357.2019.1578409.

Kaur J, Politis C, Jacobs R. Salivary 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine, malondialdehyde, vitamin C, and vitamin E in oral pre-cancer and cancer: diagnostic value and free radical mechanism of action. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:315–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-015-1506-4.

Agha-Hosseini F, Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Farmanbar N, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress status and DNA damage in saliva of human subjects with oral lichen planus and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:736–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01172.x.

Kumar A, Pant MC, Singh HS, Khandelwal S. Determinants of oxidative stress and DNA damage (8-OhdG) in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:309–15. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509X.104499.

Bahar G, Feinmesser R, Shpitzer T, Popovtzer A, Nagler RM. Salivary analysis in oral cancer patients: DNA and protein oxidation, reactive nitrogen species, and antioxidant profile. Cancer. 2007;109:54–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22386.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29:372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

Georgaki M, Theofilou I, Pettas E, Stoufi E, Younis RH, Kolokotronis A, et al. Understanding the complex pathogenesis of oral cancer: a comprehensive review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021;5:566–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2021.04.004.

Bashir A, Khan ZA, Maqsood A, Prabhu N, Saleem MM, Alzarea BK, et al. The evaluation of clinical signs and symptoms of malignant tumors involving the Maxillary Sinus: recommendation of an examination sieve and risk alarm score. Healthc (Basel). 2023;11:194. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020194.

Klaunig JE. Oxidative stress and Cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:4771–8. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612825666190215121712.

Lin Y, Jiang M, Chen W, Zhao T, Wei Y. Cancer and ER stress: mutual crosstalk between autophagy, oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:109249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109249.

Senghore T, Li YF, Sung FC, Tsai MH, Hua CH, Liu CS, et al. Biomarkers of oxidative stress Associated with the risk of potentially malignant oral disorders. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5211–6. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.12844.

Prieto-Correa JR, Bologna-Molina R, González-González R, Molina-Frechero N, Soto-Ávila JJ, Isiordia-Espinoza M, et al. DNA oxidative damage in oral cancer: 8-hydroxy-2´-deoxyguanosine immunoexpression assessment. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2023;28:e530–8. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.25924.

Zhou Y, Liu Z. Saliva biomarkers in oral disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2023;548:117503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2023.117503.

Min H, Zhu S, Safi L, Alkourdi M, Nguyen BH, Upadhyay A, et al. Salivary Diagnostics in Pediatrics and the Status of Saliva-based biosensors. Biosens (Basel). 2023;13:206. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios13020206.

Britze TE, Jakobsen KK, Grønhøj C, von Buchwald C. A systematic review on the role of biomarkers in liquid biopsies and saliva samples in the monitoring of salivary gland cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2023;143:709–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2023.2238757.

Khijmatgar S, Yong J, Rübsamen N, Lorusso F, Rai P, Cenzato N, et al. Salivary biomarkers for early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and head/neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2024;60:32–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdsr.2023.10.003.

Krishna Prasad RB, Sharma A, Babu HM. An insight into salivary markers in oral cancer. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2013;10:287–95.

Nagler RM. Saliva as a tool for oral cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:1006–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.005.

Kumar M, Nanavati R, Modi TG, Dobariya C. Oral cancer: etiology and risk factors: a review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12:458–63. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.186696.

Shah SU, Nigar S, Yousofi R, Maqsood A, Altamash S, Lal A, et al. Comparison of triamcinolone with pentoxifylline and vitamin E efficacy in the treatment of stage 2 and 3 oral submucous fibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231200757. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121231200757.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.-S.; methodology, M.A.A.-S.; software, M.A.A.-S.; validation, M.A.A.-S, and M.N.-V.; formal analysis, M.A.A.-S, A.H. and M.N.-V.; investigation, M.A.A.-S.; resources, M.A.A.-S.; data curation, M.A.A.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.A.-S.; writing—review and editing, M.A.A.-S, L.S.E.-V and A.H.; visualization, M.A.A.-S, L.S.E.-V and A.H.; supervision, M.A.A.-S, and A.H.; project administration, M.A.A.-S and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alarcón-Sánchez, M.A., Escoto-Vasquez, LS. & Heboyan, A. Salivary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine levels in patients with oral cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 24, 960 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12746-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12746-0