Abstract

Objective

PD-L1 was an important biomarker in lung adenocarcinoma. The study was to confirm the most important factor affecting the expression of PD-L1 remains undetermined.

Methods

The clinical records of 1045 lung adenocarcinoma patients were retrospectively reviewed. The High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) scanning images of all the participants were analyzed, and based on the CT characteristics, the adenocarcinomas were categorized according to CT textures. Furthermore, PD-L1 expression and Ki67 index were detected by immunohistochemistry. All patients underwent EGFR mutation detection.

Results

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that smoking (OR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.04–2.89, p = 0.004), EGFR wild (OR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.11–2.07, p = 0.009), micropapillary subtypes (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.46–2.89, p < 0.0001), and high expression of Ki67 (OR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.44–2.82, p < 0.0001) were independent factors which influence PD-L1 expression. In univariate analysis, tumor size > 3 cm and CT textures of pSD showed a correlation with high expression of PD-L1. Further analysis revealed that smoking, micropapillary subtype, and EGFR wild type were also associated with high Ki67 expression. Moreover, high Ki67 expression was observed more frequently in tumors of size > 3 cm than in tumors with ≤ 3 cm size as well as in CT texture of pSD than lesions with GGO components. In addition, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that only lesions with micropapillary components correlated with pSD (OR: 3.96, 95% CI: 2.52–5.37, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

This study revealed that in lung adenocarcinoma high Ki67 expression significantly influenced PD-L1 expression, an important biomarker for immune checkpoint treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is the major cause of increased mortality by cancer worldwide, and Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common pathological subtype of NSCLC [1].

Computed Tomography (CT) is used for diagnosing lung cancer, and persistent pulmonary ground-glass opacity (GGO) on CT is closely associated with LUAD [2]. In high-resolution CT (HRCT), GGO is defined as hazy pulmonary nodules with lesions that lack obscure bronchial structures or pulmonary vessels [3]. According to the proportion of ground glass components, pulmonary nodules can be classified as pure GGO nodules (pGGO), mixed GGO nodules (mGGO), and solid nodules (SN) [4]. In LUAD, various GGO types are associated with different prognoses [5].

Proliferation is a crucial characteristic of LUAD progression. The Ki-67 labeling index is a widely used prognostic biomarker that is estimated by the immunohistochemical labeling of nuclear antigen Ki-67 [6]. Ki67 is a DNA-binding nuclear protein, which is expressed throughout the proliferative phases of the cell cycle and absent in the quiescent (G0) phases [7, 8]. Furthermore, the literature suggests that Ki67 is correlated with the prognosis of lung cancer [9, 10].

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is present on the cell surface and is a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) superfamily. It mediates cell signaling by extra-cellular growth factor; therefore, targeted therapies for EGFR mutation with better clinical efficacy have been a hotspot in research [11].

In recent years, monoclonal antibodies against immune checkpoints have made breakthroughs across many tumor types, especially in melanoma, as well as lung, kidney, and bladder cancers [12]. It has been suggested that the activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway helps tumor cells escape T-cell cytolysis and facilitate cancer initiation. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can reactivate T-cell activity by directly binding PD-1 or its ligand PD-L1, thereby blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and ultimately eliminating tumor cells [13].

The literature suggests that PD-L1 expression is correlated with male gender, smoking [14, 15], high Ki67 expression [16], wild-type EGFR status [13, 17, 18], and absence of GGO with CT texture of LUAD [3]. However, the dominant factors remain undetermined. Because of the importance of PD-L1, it is an essential research topic.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by The Ethics Review Board of Huadong Hospital, Affiliated with Fudan University, and followed the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived because the study was retrospective.

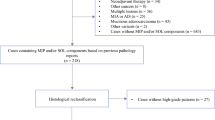

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

According to the inclusion criteria, patients who (a) underwent surgical resection, (b) were pathologically diagnosed with LUAD, and (c) had a CT scan before surgery were included in the study. Of 2000 patients, 955 were excluded as (a) they lacked preoperative CT images (n = 50), (b) their lesions manifested as diffuse miliary nodules in the two lungs (n = 22), (c) they had multiple lesions (n = 335), (d) their lesions were obscured with atelectasis, pneumonia or massive pleural effusion (n = 31), or (e) their PD-L1 expression status was not available (n = 517). Finally, 1045 patients were included in this study.

Patients’ general characteristics

All the patient’s medical records were reviewed and their data on sex, age, smoking history, Ki67, T staging, PD-L1 expression, EGFR mutation status, and pathological subtypes, were acquired. These factors were selected because (1) Ki67 is used to estimate a cell’s proliferation rate [19]. Furthermore, it has been reported that signaling pathways of PD-L1 and Ki67 interact with each other. (2) EGFR is a druggable target in LUAD [20]. (3) Smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer [21]. (4) T staging is a basic characteristic of cancer [22]. (5) The expression of PD-L1 has been associated with some subtypes [23].(6) A study showed that PD-L1 expression was associated with absence of surrounding ground glass opacity [13].

Computed tomographic assessment

Preoperative chest CT was performed using three scanners: GE Discovery CT750 HD, 64-slice Light Speed VCT (GE Medical Systems), and Somatom Definition flash with the following parameters: 120 kVp, 100–200 mAs, pitch = 0.75–1.5, and collimation = 1–1.25 mm, respectively. All imaging data were reconstructed using a medium sharp reconstruction algorithm of 1–1.25 mm thickness.

Interpretation of computed tomographic images

The CT images were retrospectively interpreted by a clinical radiologist (H.Q.L) with 35 years of experience and two other radiologists (F.L and E.N.W) with 10 years of experience, independently. The radiologists were blinded to clinical data. For the final CT feature value, the majority class was used, and CT images were read at both mediastinal (width = 350 HU; level = 40 HU) and lung (width = 1500 HU; level = -650 HU) window settings. Furthermore, the lesion location, size, and texture were retrospectively evaluated, and the long axis diameter at the lesion’s maximal section was measured. The lesion with only GGO was classified as pGGO, that with > 50% but < 100% was classified as a GGO predominant nodule (mGGO), while that with > 1% but ≤ 50% GGO was defined as a solid predominant nodule (mSD). Moreover, the lesions that lacked GGO were classified as a pure solid nodule (pSD). During statistical analysis, the mGGO and mSD were combined and called mGGO.

Histopathologic analysis

The LUAD tumors were identified and classified based on the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification system [24]. Furthermore, each lesion’s histological subtype (acinar, lepidic, papillary, micropapillary, and solid) was also assessed.

The hot-spot area was determined under the low-power field for Ki67 and PD-L1 assessment. A total of 1000 tumor cells were counted under 400 × magnification, and the positive tumor cell percentage was assessed.

The samples were stained with Ki-67 antibodies for immunohistochemistry, and the positively stained cells with the highest density were quantified. A total of 1000 tumor cells were counted under 400 × magnification. The positive percentage of tumor cells was denoted as the Ki-67 labeling index. The expression values of < 10% indicate low Ki67 expression, while the expression values of ≥ 10% depict high Ki67 expression.

The immunohistochemistry of PD-L1 antibody labeled slides was performed on the Dako Autostainer Link 48 platform using the PD-L1 22C3 antibody. The tumor proportion score (TPS) was used to evaluate PD-L1 expression in tumor cells. PD-L1 positivity was evaluated using a tumor cell expression (TC) method = (number of PD-L1 stained tumor cell/total tumor cell × 100) Where, ≤ 1% = negative, > 1% = positive. All the samples were evaluated by two expert pathologists by following the method of Kim T et al. [25].

Furthermore, using histological specimens of LUAD patients, the EGFR mutation status of exon 18–21 was detected with a polymerase chain reaction-based amplified refectory mutation system (ARMS) with the help of a Human EGFR Gene Mutation Fluorescence Polymerase Chain Reaction Diagnostic Kit (AmoyDx, China).

Statistical analysis

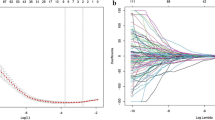

All the statistical analysis was performed via SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The differences in categorical variables distribution were evaluated by the χ2 test, and differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent factors that can influence the expression of PD-L1. The final model was selected with the backward elimination method, with a cutoff p-value of 0.05.

Results

The demographics

A total of 1045 patients were included in this study, including 443 men and 577 women. The age ranged from 22 to 90 years, with an average of 63.3 years old, and among these, 85 had a smoking history.

The correlation between clinical features and expression of PD-L1

Table 1 indicates that the PD-L1 expression rates were significantly higher (a) in men [143 of 457 (31.3%)] than in women [131 of 588 (22.3%)] (OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.20–2.01, p = 0.001) (b) in smokers [38 of 85 (44.7%)] than in nonsmokers [236 of 960 (24.6%)] (OR: 2.480, 95% CI: 1.58–3.90, p < 0.0001) (c) in high expression of Ki67 patients [174 of 461 (37.7%)] than in low expression of KI67 patients [100 of 584 (17.1%)] (OR: 2.93, 95% CI: 2.20–3.91, p < 0.0001) and (d) in EGFR wild type [115 of 334 (34.4%)] than in EGFR mutation type [159 of 711 (22.4%)] (OR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.37–2.43, p < 0.0001). (e) in lesions with micropapillary components [122 of 277 (44.0%)] than in without micropapillary components [153 of 768 (19.9%)] (OR: 3.2, 95% CI: 2.40–4.30, p < 0.0001). Although the p-value was < 0.05 for the lepidic, papillary, and solid components, these pathological subtypes were negatively correlated with the expression of PD-L1. No significant association was observed between age and PD-L1 expression.

The correlation between CT texture and expression of PD-L1

High expression of PD-L1 was more frequent in pSD [145 of 406 (35.7%)] than in pGGO [67 of 329 (20.3%)] (OR: 2.17, 95% CI: 1.55–3.04, p < 0.0001) (Table 1). No significant difference in PD-L1 expression was observed between pGGO and mGGO.

The correlation between the T or N stage of the tumor and the expression of PD-L1

Tumors of ≥ T2 stage (tumor diameter > 3 cm) more frequently indicated high expression of PD-L1 [47 of 129 (36.4%)] than T1a stage [37 of 177 (20.9%)]. Furthermore, there were no PD-L1 expression differences between other stages and T1 stage tumors. Because there were reduced N-positive tumors, the N stage had no significance.

Multivariable analysis of factors influencing the expression of PD-L1

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (of variables shown in Table 1) showed that 4 independent variables, including smoking, EGFR mutation status, Ki67 expression, and micropapillary subtype, were correlated with PD-L1 expression. High expression of PD-L1 was more frequently observed in individuals who smoked (OR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.04–2.89, p = 0.004), had wild-type EGFR (OR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.11–2.07, p = 0.009), high Ki67 expression (OR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.44–2.82, p < 0.0001), and micropapillary subtypes (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.46–2.89, p < 0.0001), suggesting that these were independent factors influencing PD-L1 expression (Table 2).

Association between factors influencing the expression of PD-L1 and expression of Ki67

The association of smoking, some specific histopathological subtypes, and EGFR wild type with Ki67 expression were also analyzed (Table 3). Ki67 expression was observed more frequently in smokers [50 of 85 (58.8%)] than in nonsmokers [411 of 960 (42.8%)] (p = 0.004), in those with EGFR wild type [176 of 334 (52.7%)] than in those with EGFR mutation type [285 of 711 (40.1%)] (p = 0.0001), as well as in patients indicating lesions with micropapillary component [201 of 277 (72.6%)] than in those who did not have these lesions [261 of 768 (34.0%)] (p < 0.0001). There was no correlation between the solid subtype and the expression of Ki67.

Association of tumor diameter with CT textures and Ki67 expression

The association of Ki67 expression with tumors of > 3 and ≤ 3 cm size was determined, which revealed that high Ki67 expression was more frequently observed in tumors of > 3 cm [85 of 129 (65.9%)] than in ≤ 3 cm size [376 of 916 (41.0%)] ( p < 0.0001). For the CT textures, Ki 67 high expression was observed more frequently in pSD tumors [278 of 406 (68.5%)] than in non-pSD tumors [183 of 639 (28.6%)] (p < 0.0001) (Table 4).

Multivariable logistic regression correlation analysis between CT texture of pSD and histopathological subtypes

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 5) showed that only lesions with micropapillary components correlated with pSD (OR: 3.96, 95% CI: 2.52–5.37, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway have been widely used in advance NSCLC for better efficacy and safety [26, 27]. Studies elucidated that PD-L1 ≥ 1% was positively associated with the major response (MPR), pathological complete response (PCR), 3-year overall survival (OS), and disease-free survival (DFS) [28]. Therefore, elucidating the associated factors influencing the expression of PD-L1 is essential.

This study revealed that the expression of PD-L1 was correlated with male smoking, high Ki67 expression, and wild-type EGFR in LUAD. Q. Zhu et al. also revealed an association of PD-L1 with male gender and smoking history, supported by several other studies [14, 16, 17, 29, 30]. Q. Chen et al. revealed that EGFR-mutated patients showed relatively lower PD-L1 expression than wild-type patients [17] Furthermore, it has been repetitively indicated that EGFR wild-type tumors were significantly more likely to express PD-L1 than EGFR-mutated tumors [13, 17, 18, 31,32,33]. M. Evans et al. analyzed PD-L1 expression in 10,005 NSCLC cases and found that EGFR wild-type tumors were significantly more likely to express PD-L1 than mutated tumors [15].

The multivariable regression analysis in this study indicated that smoking, wild-type EGFR, and high expression of Ki67 were independent factors of correlated expression of PD-L1. To elucidate the dominant factor among these three, smoking and EGFR wild type were correlated with high Ki67 expression. It was found that whether in smoker or wild EGFR patients, the frequency of high Ki67 expression was more than in counterparts. Furthermore, either in EGFR mutation or wild lesions, high expression of PD-L1 always correlated with high Ki67 expression. It is noteworthy that smoking and wild-type EGFR influenced PD-L1 expression by increasing Ki67 expression. Q. Zhu et al., by linear regression analysis, revealed a positive association between the expression of PD-L1 and Ki-67 [16]. Furthermore, Y. Zhao et al. found that patients with positive PD-L1 expression had a significantly higher incidence of more advanced tumor stage and Ki-67 index [34] Additionally, pSD is more frequently expressed in PD-L1. T. Wu et al. and K. Takada et al. demonstrated that the absence of surrounding GGO was significantly associated with the expression of PD-L1, consistent with the results of this research [13, 35]. Moreover, Mimae et al. revealed that pure solid LUAD had a more advanced T stage [36]. Studies showed that pure solid tumors exhibited more aggressive behavior (lymphatic, vascular, and pleural invasions or lymph node metastasis) [36,37,38]. Solid tumors exhibit more malignant behavior compared with mixed tumors [37]. Q. Chen et al. analyzed 1071 NSCLC, including 847 LUAD patients, and demonstrated that in this subgroup, high PD-L1 expression was associated with advanced T stage, consistent with other studies [17, 29, 39, 40]. Similarly, J. Zhou et al. suggested that there was almost no PD-L1 expression in AIS (adenocarcinoma in situ) or MIA (minimally invasive adenocardinoma) [41]. However, PD-L1 expression was correlated with the invasiveness of LUAD. The percentages of PD-L1 positive in IA-1, -2, and − 3 were 7.22, 11.29, and 14.20%, respectively. To compare with the study, we analyzed the PD-L1 expression in different diameters of pSD, which indicated no correlation between tumor diameter and PD-L1 expression except in those with > 3 cm size, reaching marginal statistical significance. Further analysis showed that in this group, Ki67 expression was significantly higher than its counterpart. Furthermore, Ki67 was the dominant factor influencing the expression of PD-L1. It was suggested by J. Zhou et al. [41] that reduced PD-L1 expression in AIS or MIA was due to the low expression of Ki67 and that advanced stage LUAD corresponded to high expression of Ki67.

Meta-analysis has indicated that high Ki-67 expression is a valuable predictor for advanced TNM stages [9]. This study also showed that there was no difference in PD-L1 expression in pGGO and mGGO lesions and revealed the importance of the GGO component for LUAD. The previous studies stress the importance of GGO absence in the expression of PD-L1, but the expression differences of different GGO were not concluded [13, 35]. X. Yang et al. performed a large study on 2022 nodules from 1844 patients and revealed high PD-L1 expression in 9, 12, and 17% of pGGO, mGGO, and solid nodules; however, they did not compare the difference between pGGO and mGGO; therefore, cannot be compared with the results of the current study [42].

This study indicated that large tumor size and CT texture of pSD in LUAD were correlated with high PD-L1 expression, consistent with the results of previous studies [13,14,15]. Furthermore, large tumor size and pSD of LUAD also indicated high Ki67 expression, suggesting a relationship between the expressions of Ki67 and PD-L1. Further analysis found that pSD was correlated with the pathological subtype of micropapillary, which was observed both in higher expression of PD-L1 and Ki67. These results were partially consistent with previous reports [29, 43, 44]. However, no association was observed between the expression of PD-L1 and the pathological subtype of solid [23, 45]. In addition, there was no correlation between the expression of Ki67, pSD, and the pathological subtype of solid. These results are controversial and therefore, require further studies.

Interestingly, this study’s result of pGGO and mGGO had similar expression of PD-L1, consistent with studies on the prognosis of LUAD [46,47,48,49,50]. These studies indicated that the GGO predicted favorable OS (overall survival) and DFS (disease-free survival). It has also been revealed that PD-L1 and Ki 67 were correlated with poor prognosis [9, 10, 51]. Furthermore, LUAD with GGO component has been suggested to have low expression of PD-L1 and Ki67, which were poor prognosis biomarkers.

The literature has indicated that PD-L1 could promote cancer growth. Liu S et al. [52] found that the PD-L1 expression in breast cancer tissues correlates with lymph node metastasis. Furthermore, Mu L et al. [53] revealed that tumor-associated fibroblasts promoted the growth of gastric cancer cell lines by upregulating PD-L1 expression. Qu QX et al. [54] revealed that PD-L1 promoted cancer cell growth in ovarian cancer. Moreover, Du W et al. [55] showed that nuclear PD-L1 could promote NSCLC cell proliferation via the Growth Arrest-Specific 6 (Gas6)/MerTK signaling pathway. In addition, they also indicated that Nuclear PD-L1 (nPD-L1) coupled with transcription factor Sp1, regulated the synthesis of Gas6 mRNA and promoted Gas6 secretion to activate the MerTK signaling pathway. Activation of MerTK signaling by its ligands Gas6 and Protein S1 (PROS1) promoted cell proliferation.

These aforementioned studies further validate the results of this study. The factors such as smoking, EGFR wild type, and micropapillary promoted the proliferation of LUAD by upregulating the expression of PD-L1, therefore, the expressions of PD-L1 and Ki67 could be significantly related.

The summary of the above data suggests that expression of Ki67 and PD-L1 increased with the progression of cancer, and with the development of cancer, many genes related to Ki67 and PD-L1 are activated and amplified. Furthermore, the expression of Ki67 and PD-L1 act as potent weapons of cancer, which correlated with each other, where the expression of Ki67 promoted cancer, and that of PD-L1 helped tumor cells escape T cell attack. Moreover, Ki67 and PD-L1 become stronger with the progression of cancer. Therefore, the goal should be to reduce these factors to protect patients who have cancer.

Limitations

(1) It is a retrospective study with a small sample size, which may have caused a selection bias. (2) The cases were limited to LUAD, and other histological subtypes were not addressed. (3) No survival data were provided in the study.

Conclusion

In summary, this study showed that in LUAD, PD-L1 expression was correlated with male gender, smoking, expression of Ki67, and wild-type EGFR. Furthermore, it was inferred that the high expression of KI67 was the key factor associated with increased PD-L1 and other factors acting via KI67.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P, Mitchell A, Bolejack V. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncology: Official Publication Int Association Study Lung Cancer. 2016;11(1):39–51.

Kim HY, Shim YM, Lee KS, Han J, Yi CA, Kim YK. Persistent pulmonary nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histopathologic comparisons. Radiology. 2007;245(1):267–75.

Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697–722.

MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, Lee KS, Leung ANC, Mayo JR, Mehta AC, Ohno Y, Powell CA, Prokop M, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner society 2017. Radiology. 2017;284(1):228–43.

Kinoshita F, Toyokawa G, Matsubara T, Kozuma Y, Haratake N, Takamori S, Akamine T, Hirai F, Takenaka T, Tagawa T, et al. Prognosis of early-stage part-solid and pure-solid lung adenocarcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(5):2665–70.

Chen M, Li X, Wei Y, Qi L, Sun YS. Spectral CT imaging parameters and Ki-67 labeling index in lung adenocarcinoma. Chin J cancer Res = Chung-kuo Yen Cheng Yen Chiu. 2020;32(1):96–104.

Liu Z, Feng H, Ma S, Shao W, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Sun H, Gu X, Zhang Z, Liu D. Clinicopathological characteristics of peripheral clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma with high Ki-67 expression. Translational cancer Res. 2021;10(1):152–61.

Warth A, Cortis J, Soltermann A, Meister M, Budczies J, Stenzinger A, Goeppert B, Thomas M, Herth FJ, Schirmacher P, et al. Tumour cell proliferation (Ki-67) in non-small cell lung cancer: a critical reappraisal of its prognostic role. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(6):1222–9.

Wei DM, Chen WJ, Meng RM, Zhao N, Zhang XY, Liao DY, Chen G. Augmented expression of Ki-67 is correlated with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis for lung cancer patients: an up-dated systematic review and meta-analysis with 108 studies and 14,732 patients. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):150.

Wei D, Xin Y, Rong Y, Hao Y. Correlation between the expression of VEGF and Ki67 and lymph node metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2022;2022:9693746.

Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, Feng J, Lu S, Huang Y, Li W, Hou M, Shi JH, Lee KY, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):213–22.

Konishi J, Yamazaki K, Azuma M, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H, Nishimura M. B7-H1 expression on non-small cell lung cancer cells and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their PD-1 expression. Clin cancer Research: Official J Am Association Cancer Res. 2004;10(15):5094–100.

Wu T, Zhou F, Soodeen-Lalloo AK, Yang X, Shen Y, Ding X, Shi J, Dai J, Shi J. The association between imaging features of TSCT and the expression of PD-L1 in patients with surgical resection of lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(2):e195–207.

Takeda M, Kasai T, Naito M, Tamiya A, Taniguchi Y, Saijo N, Naoki Y, Okishio K, Shimizu S, Kojima K, et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression with clone 22C3 in non-small cell lung cancer: a single institution experience. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2019;13:1179554918821314.

Evans M, O’Sullivan B, Hughes F, Mullis T, Smith M, Trim N, Taniere P. The clinicopathological and molecular associations of PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: analysis of a series of 10,005 cases tested with the 22C3 assay. Pathol Oncol Research: POR. 2020;26(1):79–89.

Zhu Q, Zhang J, Xu D, Zhao R. Association between PD-L1 and Ki-67 expression and clinicopathologic features in NSCLC patients. Am J Translational Res. 2023;15(8):5339–46.

Chen Q, Fu YY, Yue QN, Wu Q, Tang Y, Wang WY, Wang YS, Jiang LL. Distribution of PD-L1 expression and its relationship with clinicopathological variables: an audit from 1071 cases of surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12(3):774–86.

Lee SE, Kim YJ, Sung M, Lee MS, Han J, Kim HK, Choi YL. Association with PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological features in 1000 lung cancers: a large single-institution study of surgically resected lung cancers with a high prevalence of EGFR mutation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(19).

Folescu R, Levai CM, Grigoraş ML, Arghirescu TS, Talpoş IC, Gîndac CM, Zamfir CL, Poroch V, Anghel MD. Expression and significance of Ki-67 in lung cancer. Romanian J Morphology Embryol = Revue Roumaine de Morphologie et embryologie. 2018;59(1):227–33.

Tumbrink HL, Heimsoeth A, Sos ML. The next tier of EGFR resistance mutations in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40(1):1–11.

Schwartz AG, Cote ML. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:21–41.

Mountain CF. Staging of lung cancer. Yale J Biol Med. 1981;54(3):161–72.

Miyazawa T, Morikawa K, Otsubo K, Sakai H, Kimura H, Chosokabe M, Furuya N, Marushima H, Kojima K, Mineshita M, et al. Solid histological component of adenocarcinoma might play an important role in PD-L1 expression of lung adenocarcinoma. Thorac cancer. 2022;13(1):24–30.

Okada M. Subtyping lung adenocarcinoma according to the novel 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification: correlation with patient prognosis. Torac Surg Clin. 2013;23(2):179–86.

Kim T, Cha YJ, Chang YS. Correlation of PD-L1 expression tested by 22C3 and SP263 in non-small cell lung cancer and its prognostic effect on EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2020;83(1):51–60.

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–33.

Herbst RS, Giaccone G, de Marinis F, Reinmuth N, Vergnenegre A, Barrios CH, Morise M, Felip E, Andric Z, Geater S, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of PD-L1-selected patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1328–39.

Zhang F, Guo W, Zhou B, Wang S, Li N, Qiu B, Lv F, Zhao L, Li J, Shao K, et al. Three-year follow-up of neoadjuvant programmed cell death protein-1 inhibitor (Sintilimab) in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncology: Official Publication Int Association Study Lung Cancer. 2022;17(7):909–20.

Takada K, Okamoto T, Shoji F, Shimokawa M, Akamine T, Takamori S, Katsura M, Suzuki Y, Fujishita T, Toyokawa G, et al. Clinical significance of PD-L1 protein expression in surgically resected primary lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncology: Official Publication Int Association Study Lung Cancer. 2016;11(11):1879–90.

Liam CK, Yew CY, Pang YK, Wong CK, Poh ME, Tan JL, Soo CI, Loh TC, Chin KK, Munusamy V, et al. Common driver mutations and programmed death-ligand 1 expression in advanced non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never smokers. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):659.

Mansour MSI, Malmros K, Mager U, Ericson Lindquist K, Hejny K, Holmgren B, Seidal T, Dejmek A, Dobra K, Planck M et al. PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer specimens: association with clinicopathological factors and molecular alterations. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9).

Li C, Liu J, Xie Z, Zhu F, Cheng B, Liang H, Li J, Xiong S, Chen Z, Liu Z, et al. PD-L1 expression with respect to driver mutations in non-small cell lung cancer in an Asian population: a large study of 1370 cases in China. Therapeutic Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835920965840.

Yanagawa N, Shiono S, Endo M, Ogata SY, Yamada N, Sugimoto R, Osakabe M, Uesugi N, Sugai T. Programmed death ligand 1 protein expression is positively correlated with the solid predominant subtype, high MIB-1 labeling index, and p53 expression and negatively correlated with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2021;108:12–21.

Zhao Y, Shi F, Zhou Q, Li Y, Wu J, Wang R, Song Q. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 in advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. Medicine. 2020;99(45):e23172.

Takada K, Toyokawa G, Tagawa T, Shimokawa M, Kohashi K, Haro A, Osoegawa A, Oda Y, Maehara Y. Radiological features of IDO1(+)/PDL1(+) lung adenocarcinoma: a retrospective single-institution study. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(9):5295–303.

Mimae T, Miyata Y, Tsutani Y, Shimada Y, Ito H, Nakayama H, Ikeda N, Okada M. Role of ground-glass opacity in pure invasive and lepidic component in pure solid lung adenocarcinoma for predicting aggressiveness. JTCVS open. 2022;11:300–16.

Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Yamanaka T, Nakayama H, Okumura S, Adachi S, Yoshimura M, Okada M. Solid tumors versus mixed tumors with a ground-glass opacity component in patients with clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: prognostic comparison using high-resolution computed tomography findings. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(1):17–23.

Iwano S, Kishimoto M, Ito S, Kato K, Ito R, Naganawa S. Prediction of pathologic prognostic factors in patients with lung adenocarcinomas: comparison of thin-section computed tomography and positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Cancer Imaging: Official Publication Int Cancer Imaging Soc. 2014;14(1):3.

Wu J, Sun W, Wang H, Huang X, Wang X, Jiang W, Jia L, Wang P, Feng Q, Lin D. The correlation and overlaps between PD-L1 expression and classical genomic aberrations in Chinese lung adenocarcinoma patients: a single center case series. Cancer Biology Med. 2019;16(4):811–21.

Zhao M, Zhan C, Li M, Yang X, Yang X, Zhang Y, Lin M, Xia Y, Feng M, Wang Q. Aberrant status and clinicopathologic characteristic associations of 11 target genes in 1,321 Chinese patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Disease. 2018;10(1):398–407.

Zhou J, Lin H, Ni Z, Luo R, Yang D, Feng M, Zhang Y. Expression of PD-L1 through evolution phase from pre-invasive to invasive lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):18.

Yang X, Xiao Y, Hu H, Qiu ZB, Qi YF, Wang MM, Wu YL, Zhong WZ. Expression changes in programmed death ligand 1 from precancerous lesions to invasive adenocarcinoma in subcentimeter pulmonary nodules: a large study of 2022 cases in China. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30(12):7400–11.

Forest F, Casteillo F, Da Cruz V, Yvorel V, Picot T, Vassal F, Tiffet O. Péoc’h M: heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma metastasis is related to histopathological subtypes. Lung cancer (Amsterdam Netherlands). 2021;155:1–9.

Ci B, Yang DM, Cai L, Yang L, Girard L, Fujimoto J, Wistuba II, Xie Y, Minna JD, Travis W, et al. Molecular differences across invasive lung adenocarcinoma morphological subgroups. Translational lung cancer Res. 2020;9(4):1029–40.

Cruz-Rico G, Avilés-Salas A, Popa-Navarro X, Lara-Mejía L, Catalán R, Sánchez-Reyes R, López-Sánchez D, Cabrera-Miranda L, Aquiles Maldonado-Martínez H, Samtani-Bassarmal S, et al. Association of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in tumor cells. Pathol Oncol Research: POR. 2021;27:597499.

Fu F, Zhang Y, Wen Z, Zheng D, Gao Z, Han H, Deng L, Wang S, Liu Q, Li Y, et al. Distinct prognostic factors in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer with radiologic part-solid or solid lesions. J Thorac Oncology: Official Publication Int Association Study Lung Cancer. 2019;14(12):2133–42.

Hattori A, Hirayama S, Matsunaga T, Hayashi T, Takamochi K, Oh S, Suzuki K. Distinct clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis based on the presence of ground glass opacity component in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncology: Official Publication Int Association Study Lung Cancer. 2019;14(2):265–75.

Pan XL, Liao ZL, Yao H, Yan WJ, Wen DY, Wang Y, Li ZL. Prognostic value of ground glass opacity on computed tomography in pathological stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(33):10222–32.

Li M, Xi J, Sui Q, Kuroda H, Hamanaka K, Bongiolatti S, Hong G, Zhan C, Feng M, Wang Q, et al. Impact of a ground-glass opacity component on c-stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;35(4):783–95.

Hamada A, Suda K, Fujino T, Nishino M, Ohara S, Koga T, Kabasawa T, Chiba M, Shimoji M, Endoh M, et al. Presence of a ground-glass opacity component is the true prognostic determinant in clinical stage I NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3(5):100321.

Wang A, Wang HY, Liu Y, Zhao MC, Zhang HJ, Lu ZY, Fang YC, Chen XF, Liu GT. The prognostic value of PD-L1 expression for non-small cell lung cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncology: J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Association Surg Oncol. 2015;41(4):450–6.

Liu S, Chen S, Yuan W, Wang H, Chen K, Li D, Li D. PD-1/PD-L1 interaction up-regulates MDR1/P-gp expression in breast cancer cells via PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways. Oncotarget. 2017;8(59):99901–12.

Mu L, Yu W, Su H, Lin Y, Sui W, Yu X, Qin C. Relationship between the expressions of PD-L1 and tumour-associated fibroblasts in gastric cancer. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):1036–42.

Qu QX, Xie F, Huang Q, Zhang XG. Membranous and cytoplasmic expression of PD-L1 in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochemistry: Int J Experimental Cell Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;43(5):1893–906.

Du W, Zhu J, Zeng Y, Liu T, Zhang Y, Cai T, Fu Y, Zhang W, Zhang R, Liu Z, et al. KPNB1-mediated nuclear translocation of PD-L1 promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation via the Gas6/MerTK signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(4):1284–300.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the reviewers who participated in the review and MJEditor (www.mjeditor.com) for their linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL and EW reviewed the literature and collated and analysed the information. HL conceived and designed the study as well as drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Review Board of Huadong Hospital, Affiliated with Fudan University approved this retrospective study (No.20230108) and it was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, F., Wang, E. & Liu, H. Factors correlating the expression of PD-L1. BMC Cancer 24, 642 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12400-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12400-9