Abstract

Background

To predict pathological complete response (pCR) in patients receiving neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy (nICT) for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), we explored the factors that influence pCR after nICT and established a combined nomogram model.

Methods

We retrospectively included 164 ESCC patients treated with nICT. The radiomics signature and hematology model were constructed utilizing least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, and the radiomics score (radScore) and hematology score (hemScore) were determined for each patient. Using the radScore, hemScore, and independent influencing factors obtained through univariate and multivariate analyses, a combined nomogram was established. The consistency and prediction ability of the nomogram were assessed utilizing calibration curve and the area under the receiver operating factor curve (AUC), and the clinical benefits were assessed utilizing decision curve analysis (DCA).

Results

We constructed three predictive models.The AUC values of the radiomics signature and hematology model reached 0.874 (95% CI: 0.819–0.928) and 0.772 (95% CI: 0.699–0.845), respectively. Tumor length, cN stage, the radScore, and the hemScore were found to be independent factors influencing pCR according to univariate and multivariate analyses (P < 0.05). A combined nomogram was constructed from these factors, and AUC reached 0.934 (95% CI: 0.896–0.972). DCA demonstrated that the clinical benefits brought by the nomogram for patients across an extensive range were greater than those of other individual models.

Conclusions

By combining CT radiomics, hematological factors, and clinicopathological characteristics before treatment, we developed a nomogram model that effectively predicted whether ESCC patients would achieve pCR after nICT, thus identifying patients who are sensitive to nICT and assisting in clinical treatment decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The incidence rate of esophageal cancer is the seventh-highest worldwide among all cancers, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) was the diagnosis made in more than 90% of cases in China [1, 2]. The primary therapeutic method for locally advanced ESCC is surgery, but it has not yet achieved satisfactory outcomes. To increase patient survival rates, neoadjuvant treatments such as targeted therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy were introduced. Several clinical studies on neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy (nICT) for locally advanced ESCC are ongoing. Preliminary findings indicated that esophagectomy for esophageal cancer after nICT showed favorable efficacy and safety, and patients who received nICT exhibited satisfactory pathological complete response (pCR) and R0 resection rates [3,4,5,6]. The prognostic survival for patients with pCR is much better than that of non-pCR and may be able to delay or avoid surgery, thus demonstrating the great promising nICT is as a neoadjuvant treatment for ESCC [7,8,9].

Only 20%-40% of ESCC patients achieve a pCR after nICT because of tumor heterogeneity [6, 10, 11]. In contrast, many patients not only end up without obvious treatment reactions and cannot achieve practical benefits but will also experience the costly and dangerous side effects of medications. Therefore, the prediction of treatment response significantly affects the implementation of nICT. Relevant research reports show that tumor mutational burden, the ratio of monocytes to lymphocytes, PD-1/PD-L1 expression, high microsatellite instability, and other biomarkers are associated with immunotherapy effectiveness [12,13,14]. There are also reports that inflammatory markers, circulating lymphocyte subtypes, and numbers of blood cells are strongly linked to patient survival and therapeutic response [15]. Unfortunately, there are no reliable biomarkers to forecast how ESCC patients would respond to therapy following nICT.

Radiomics is a high-throughput method for obtaining a great deal of data from images. Through deeper mining of massive data, radiomics can provide a series of valuable auxiliary treatment methods for the diagnosis of disease [16], the evaluation of therapeutic response [17], and the prediction of lymph node metastasis [18]. Previous studies have reported that radiomics is an efficient way for predicting the therapeutic response of ESCC after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) [19] and can aid in making clinical treatment decisions. Biomarkers obtained from biopsy require invasive examination and a series of time-consuming and complex laboratory procedures. However, it is more valuable to explore noninvasive biomarkers for predicting the therapeutic response of ESCC patients after nICT.

A nomogram is a numerical estimation model that includes many complex factors that can clearly and intuitively predict the probability of event occurrence. Numerous nomogram models for prediction have been constructed and are frequently utilized in cancer prediction modeling [20, 21]. To predict the pCR of ESCC patients after nICT, we explored the factors that influence pCR after nICT and established a combined nomogram model.

Methods

Study design

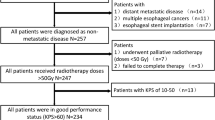

Fig. 1 shows the research procedure, which is comprehensively described by the following methods.

The research workflow. After the patient was enrolled, radiomics and hematology analyses were conducted separately, using LASSO regression to reduce the dimensionality of features. Then, radScore and hemScore were calculated, and they were combined with independent factors influencing pCR to develop a nomogram. Evaluated the predictive ability of three models, including ROC curve, calibration curve, DCA, etc.

Patients

This study retrospectively collected 285 patients who received nICT along with esophagectomy at our hospital from September 2020 to April 2023. The institutional review board (IRB) of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute authorized our study (approval number: SDTHEC2023001010), and the IRB exempted informed consent. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (a) verified by histopathology as ESCC; (b) standard non-contrast chest CT scan before treatment; and (c) received nICT and underwent esophagectomy. The exclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (a) treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other anticancer therapies prior to the baseline CT scans; (b) had other concurrent tumors; (c) had incomplete clinical features or records; and (d) had poor-quality CT images or primary tumors that were too small to be identified. There were 164 patients included after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 2).

Treatment protocol

Every patient received 2–4 cycles of immunochemotherapy and underwent open or laparoscopic thoracoscopic McKeown surgery at 4–6 weeks after treatment. The chemotherapy regimens used were fluorouracil (5-FU, teysuno, or capecitabine) or paclitaxel (albumin-binding paclitaxel or docetaxel) combined with platinum (cisplatin, nedaplatin, or oxaliplatin). A PD-1 inhibitor was chosen for the immunotherapy regimen (camrelizumab, tislelizumab, pembrolizumab, toripalimab, or sintilimab). The combination regimen and dosage depended on the patient's actual situation and preferences.

Data collection

Before patients received nICT, 40 potential influencing factors were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records. These indicators were divided into clinicopathological factors (n = 11) and hematological factors (n = 29). The clinicopathological factors included sex, age, smoking history, drinking history, tumor length, tumor location, tumor differentiation, cT stage, cN stage, cTNM stage (AJCC 8th edition), and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score. The hematological factors are displayed in Table S1. The outcome was whether the patient achieved pCR. Based on the AJCC (8th edition) tumor regression grade (TRG), pCR was defined as follows: (1) original tumor without viable tumor cells (TRG 0); and (2) no positive lymph nodes in the surgical specimens.

CT image acquisition and ROI segmentation

In our study, due to the well-differentiated tumor borders, non-contrast CT images before nICT were utilized for tumor segmentation and feature extraction. Each patient received a standard Philips CT scanner chest scan (Brilliance iCT 128). The following scanning protocol was used: 5-mm-thick slice reconstructions, helical scanning mode, 120 kV tube voltage, and 300–500 mA tube current.

With the patient information hidden, 2 radiologists with over 5 years of expertise performed the original tumor segmentation. Because human observations are susceptible to differences from person to person, a single radiologist segmented 100 randomly selected ESCC patients one month later to assess and confirm the repeatability of radiomics features. 2 radiologists reached a consensus on the differences in regions of interest (ROIs) through negotiation, and patients in which the radiologists were unable to reach an agreement on were excluded. All ROIs were segmented utilizing a 3D slicer (version 5.2.1).

Significantly, the clinical stage (cT stage, cN stage, and cTNM stage) of patients was determined separately by oncologists based on their gastroscopy and contrast CT, while non-contrast CT was used only for radiomics feature extraction.

Radiomics feature extraction and selection

We first performed preprocessing by resampling all ROIs to 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 and areas with HU < 0 were excluded. Radiomics features were subsequently extracted from the preprocessed ROIs utilizing PyRadiomics (version 3.6.2). The radiomics features we extracted included the following categories: first-order features, shape features, second or higher-order texture features, and the features were based on the original image obtained through the Laplace transform and wavelet transform.

Feature selection consisted of two steps: first, after preprocessing all the radiomics feature values via Z score normalization, the repeatability of radiomics features was assessed through intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis. Only the features with a P-value < 0.05 and an ICC ≥ 0.9 were screened for the next step of the analysis. Then, R software (version 4.0.6) was used to perform least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to identify features related to pCR, and the optimal parameter (λ) was chosen by five-fold cross-validation. In the process of selecting features, LASSO regression incorporates L1 regularization, which utilizes gradient optimization to fine-tune parameter coefficients, thereby balancing their relative weights and mitigating the issues of overfitting and collinearity. Due to the imbalance of our dataset, we also utilized the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) in our analysis to balance the number of patients with non-pCR against pCR [22].

Construction and evaluation of the radiomics signature, hematology model, and combined nomogram

First, a radiomics signature and a hematology model were developed using the LASSO method. Calculated the radiomics score (radScore) and hematology score (hemScore) for each patient by linearly combining the coefficient weighting of the selected features. Second, the univariate and multivariate analyses were utilized to screen out prognostic variables with P values < 0.05 for clinicopathological factors. Finally, by merging the radScore, hemScore, and clinicopathological independent factors, a combined nomogram model was constructed. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was utilized to estimate the precision of the combined nomogram, and the consistency of the combined nomogram was verified using a calibration curve. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was utilized to fully estimate and distinguish the clinical net benefit rates of the three models.

Statistical analysis

To assess the differences in clinical characteristics among non-pCR and pCR patients, continuous variables were examined utilizing the Student's t-test, while categorical variables were examined utilizing the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. The model's ability for predicting was estimated utilizing the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and DeLong test. The calibration curve was utilized to fully estimate the consistency of the model, and DCA was utilized to compare and estimate the clinical net benefit rates of the three models. Whether the predicted results of the combined nomogram fit the actual situation was determined using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. All the statistical analyses and graphical plots were generated utilizing R software (version 4.0.6). A P-value < 0.05 is defined as having statistical differences.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline clinicopathological characteristics of the 164 eligible ESCC patients were displayed in Table 1. The results revealed significant differences among non-pCR patients and pCR patients in tumor length (P = 0.025), cN stage(P = 0.040), and age (P = 0.041).

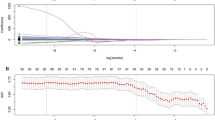

Construction and validation of radiomics signature

From every ROI, we extracted 1046 radiomics features. 8 optimal radiomics features (Table 2) related to pCR were identified through LASSO regression, and a radiomics signature was constructed to predict whether patients would achieve pCR after treatment. LASSO dimensionality reduction and the corresponding cross-validation procedures in radiomics are shown in Fig. S1. The radScore was calculated with the following formula:

\({X}_{i1}\) is the radiomics feature determined through LASSO regression, \({\beta }_{i1}\) is the regression coefficient of \({X}_{i1}\), and \({Z}_{1}\) is a constant term.

A threshold of -0.151 was determined by the Youden index to differentiate among cohorts with non-pCR versus PCR (Fig. 3A). In terms of the actual classification, there was a difference in statistics in the radScore among cohorts with non-pCR versus pCR (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). The pCR of patients can be reliably predicted by the radiomics signature, and the AUC reached 0.884 (95% CI: 0.841–0.927) for balanced data with SMOTE and 0.874 (95% CI: 0.819–0.928) for actual data (Fig. S2). The P value of the DeLong test between the two cohorts was 0.772, indicating no significant difference. Then, we used actual data to calculate the radScore and included it in subsequent analyses.

Radiomics signature and hematology model predictive performance. A: Radiomics signature value bar plot for every ESCC patient. The optimal threshold value for distinguishing among cohorts with non-pCR versus pCR is -0.151. B: Comparison of radScore among non-pCR versus pCR cohorts (P < 0.001). C: Hematology model value bar plot for every ESCC patient. The optimal threshold value for distinguishing among cohorts with non-pCR versus pCR is -0.933. D: Comparison of hemScore among non-pCR versus pCR cohorts (P < 0.001). The green color in the figure represents non-pCR patients, while the blue color represents pCR patients

Construction and validation of hematology model

We identified 29 hematology indicators as potential influencing factors for predicting the acquisition of a pCR after nICT. LASSO regression revealed that lymphocyte count (LYM), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), albumin (ALB), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) had a bearing on pCR, and a hematology model was constructed (Fig. S3, Table S2). The hemScore was calculated with the following formula:

\({X}_{i2}\) is the hematology factor identified by LASSO regression, \({\beta }_{i2}\) is the regression coefficient of \({X}_{i2}\), and \({Z}_{2}\) is a constant term.

The hematology model's AUC could reach 0.772 (95% CI: 0.699–0.845) Fig. 3 (Fig. 4A), which showed that hematological factors could effectively predict whether ESCC patients can achieve pCR after receiving nICT. The Youden index determined that -0.933 was the optimal threshold in the hematology model for differentiating among cohorts with non-pCR versus pCR (Fig. 3C). According to the actual classification, hemScores were significantly different among cohorts with non-pCR versus pCR (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3D).

Comparison of predictive performance of the combined nomogram, radiomics signature, and hematology model. A: Receiver operating characteristic curves of the combined nomogram, radiomics signature, and hematology model. B: Nomogram based on independent predictors (radScore, hemScore, cN stage, and tumor length). C: Calibration curves of the combined nomogram to estimate the consistency among the estimated pCR probability by the combined nomogram and the authentic pCR. The ideal situation is shown by the black dashed line, which acts as the reference line and shows when the predicted and actual values coincide; the actual situation of the nomogram is shown by the solid blue line, referred to as the apparent line; the bias-corrected line is shown by the solid green line, which shows the corrected nomogram's actual situation. D: The models' clinical benefits were assessed using decision curve analysis. The black horizontal line indicates that when all patients do not receive treatment, regardless of the probability threshold, there is no clinical net benefit. The gray diagonal represents the change in clinical net benefit as the probability threshold changes when all patients receive treatment

Construction and validation of the combined nomogram

We used univariate and multivariate analyses to analyze all clinicopathological factors to identify variables that were independently related to pCR (Table 3). Age, cN stage, tumor length, radScore, and hemScore were independent factors of pCR according to univariate analysis (P < 0.05); cN stage (cN0 was the reference quantity; cN1: P = 0.030; cN2: P = 0.012), radScore (P < 0.001), hemScore (P < 0.001), and tumor length (P = 0.028) had independent influences on pCR according to multivariate analysis. Therefore, we combined the above factors to construct a combined nomogram to predict whether ESCC patients could achieve pCR after nICT (Fig. 4B), which was also a demonstration of the results of multivariate analysis. Compared with those of the hematology model (AUC = 0.772, 95% CI: 0.699–0.845) and radiomics signature (AUC = 0.874, 95% CI: 0.819–0.928), the combined nomogram's AUC reached 0.934 (95% CI: 0.896–0.972), indicating a better ability for prediction (Fig. 4A). The DeLong test results demonstrated a difference in statistics in the diagnostic efficacy between the nomogram and the hematology model (P < 0.001) and the radiomics signature (P = 0.006), while there was also a statistical difference between radiomics and hematology models in diagnostic efficacy (P = 0.025). We evaluated the consistency of the combined nomogram model through a calibration curve (Fig. 4C) and the results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated a high degree of fit between the nomogram's actual and predicted date (P > 0.05). We also evaluated the clinical net benefit rates of the three models through DCA (Fig. 4D). The results showed that both the single and combined nomogram models could provide clinical benefits for patients within a certain risk threshold. In addition, when the combined nomogram model is used to guide clinical practice, it provides a greater clinical advantage to ESCC patients than the other models over a wide range of risks.

Discussion

For locally advanced ESCC patients, when nCRT is combined with esophagectomy as the standard therapy, it is difficult to achieve a precise range during the treatment process, which inevitably causes radiation toxicity to surrounding tissues and organs, as well as an increased risk of complications such as esophageal fistula or death during the perioperative period. In this situation, nICT provides a novel possibility for the therapy of ESCC patients. According to the meta-analysis by Wang et al. [23], the security and effectiveness of nICT in treating esophageal cancer after surgery demonstrated that nICT in ESCC patients is safe and effective. The efficacy of nICT and nCRT can be maintained at the same level, while the safety of nICT is better than that of nCRT. The results of this research indicate that for ESCC patients, nICT may be the best choice for the current type of neoadjuvant therapy. In addition, a recent study showed that adding radiotherapy to immunochemotherapy can increase the incidence of grade 3–4 adverse effects compared to nICT (46.7% vs. 32.8%, P = 0.04), and the rate of pCR has not significantly improved, indicating that adding radiotherapy to nICT can significantly increase the risk of serious adverse events [24]. Therefore, nICT is still the most widely used treatment in clinical trials. However, there are significant differences in whether different patients can achieve pCR after nICT, thus making accurate stratification essential for the choice of therapy. In our study, we constructed a combined nomogram model that includes the radScore obtained from CT-based radiomics features, the hemScore from baseline hematological factors, and relevant clinicopathological factors. This model potentially identifies patients who will benefit from nICT and provides guidance or reference for individualized treatment.

In our study, the majority of patients used camrelizumab and sintilimab as immunotherapy drugs (97%). Although they are still in clinical trials for nICT in ESCC, they have been approved in China as immunotherapy drugs for advanced or metastatic ESCC. The chemotherapy combined with sintilimab or camrelizumab for ESCC has been approved as the therapeutic schedule of first-line, another thing to watch out for is that camrelizumab monotherapy has been approved as the therapeutic option for second-line [25,26,27]. According to current clinical trial results, camrelizumab and sintilimab as PD-1 inhibitors for nICT can achieve a pCR of 30%-50%, which is similar in efficacy to the PD-1 inhibitors recommended in the NCCN guidelines, indicating that the use of camrelizumab and sintilimab as PD-1 inhibitors for nICT, is supported by clinical trial evidence [10, 28, 29].

Radiomics as a hot technology has been shown to have satisfactory results in predicting patient treatment responses through numerous studies. Yang et al. [30] found that the AUC for predicting esophageal cancer pCR after nCRT based on CT radiomic signatures reached 0.79 (95% CI: 0.48–1.00) in the validation group. This indicates that radiomics provides more comprehensive information on intratumoral heterogeneity, can forecast the prognosis and effectiveness of patients and is expected to accurately guide the treatment of various solid cancers [31]. Liu et al. [32] utilized CT images for constructing and verifying a clinical-radiomics model for predicting a major pathologic response after nICT in non-small cell lung cancer (AUC = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.63–0.98). And beyond that, Liang et al. [33] generated an individual radiomics nomogram that included clinicopathological independent variables and radiomics features for predicting the response after PD-1 therapy in gastric cancer patients. The nomogram's AUC reached 0.778 (95% CI: 0.732–0.776), which was superior to that of the radiomics-only. Their findings demonstrate the value of radiomics for making treatment-related decisions for patients, especially with a more satisfactory predictive performance after incorporating the patient's clinicopathologic factors. Although radiomics is widely used in various medical fields, it is still in a state of continuous exploration. Due to the limited scope of segmentation, it cannot reflect the systemic states of patients. Therefore, our study included hematological factors, which are traditional and easily accessible, to more comprehensively reflect the actual condition of patients and to improve the predictability of patients who are sensitive to nICT. According to these results, the combined nomogram model with the inclusion of the hemScore had superior performance for predicting (AUC = 0.934, 95% CI: 0.896–0.972) in contrast with the radiomics signature, which proves that it is highly important to include hematology factors and that it provides plentiful patient information compared to primary clinicopathological factors.

In this study, we included 29 hematological factors and ultimately identified four factors to establish a hematological model, namely, LYM, ALB, HDL, and NLR, which have been reported in previous tumor immunotherapy studies. Research by Valero et al. [34] reported that the NLR with a high level is related to a reduced chance of immunotherapy response and a worse prognosis, suggesting a prognostic and predictive value of the NLR in immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy. This may be due to the association of neutrophils with the tumor microenvironment. Some studies have reported that neutrophils are related to tumorigenesis, progression, and early dissemination [35, 36]. In contrast, lymphocytes, especially CD8 + T cells, play a vital function in antitumor response by causing the death of cytotoxic cells and preventing the migration and development of tumor cells [37, 38]. A decrease in the LYM may lead to inactivation of the tumor immune response, causing tumor progression and ultimately resulting in a poor prognosis [39]. A typical biomarker used to assess patients' nutritional status is the serum ALB level [40], which can indicate the inflammatory and immune conditions of patients. The results of Wu et al. [41] reported that patients with high serum ALB concentrations before immunotherapy had better survival. Perrone et al. [42] investigated the prognostic effects of factors linked to cholesterol on cancer patients, and their analysis showed that cholesterol passive diffusion (PD) levels were the only significant protective parameter for OS and PFS (P < 0.001, HR: 0.81). According to the authors, more mature HDL particles may be responsible for creating an inflammatory immunological environment that supports a better response to ICIs, which may explain the favorable correlations of cholesterol PD with OS and PFS. These studies show that the characteristics included in our hematology model are associated with the advancement and occurrence of cancers, as well as the response and prognosis of patients to treatment. Therefore, our hematology model based on these factors could be an accurate and a trustworthy reflection of the systemic condition of the patient. We also calculated the hemScore of the model and integrated it with the radScore, which reflects the patient's primary tumor status, to plot the combined nomogram associated with the patient's pCR, thus achieving a more accurate prediction of patient treatment response and providing trustworthy reference and guidance for individualized treatment of patients. Our study considered the clinical practicality evaluation of the model and plotted a DCA. The findings indicated that the combined nomogram model could provide potential clinical benefits for patients compared to any single model.

Several limitations of our study still exist. First, we did not explore the mechanism of pCR differences in ESCC patients after nICT. Second, because this study was retrospective, it is difficult to ensure the stability and consistency of the CT scanning parameters and image quality. Therefore, this study collected information only from non-contrast CT images to avoid differences in the development time and dose of contrast agents. Third, more than 30% of patients lacked some important tumor markers for ESCC, such as CA-199 and SCC. Therefore, these factors were not considered hematological factors. Finally, due to our small sample size, we did not further validate the model. In the future, our findings require independent verification with a larger number of samples to validate the applicability of the model as an effective auxiliary treatment decision-making tool.

Conclusions

A combined nomogram model based on CT, hematological factors, and clinicopathological characteristics before treatment can effectively predict whether ESCC patients will achieve pCR after nICT, thus identifying patients who are sensitive to nICT and providing assistance for deciding on clinical therapy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ESCC:

-

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- pCR:

-

Pathological complete response

- nICT:

-

Neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- nCRT:

-

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- LYM:

-

Lymphocyte count

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- TRG:

-

Tumor regression grade

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N, et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135(5):584–90.

He W, Leng X, Mao T, Luo X, Zhou L, Yan J, Peng L, Fang Q, Liu G, Wei X, et al. Toripalimab Plus Paclitaxel and Carboplatin as Neoadjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Resectable Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncologist. 2022;27(1):e18–28.

Li C, Zhao S, Zheng Y, Han Y, Chen X, Cheng Z, Wu Y, Feng X, Qi W, Chen K, et al. Preoperative pembrolizumab combined with chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (PALACE-1). Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:232–41.

Shen D, Chen Q, Wu J, Li J, Tao K, Jiang Y. The safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor with chemotherapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12(1):1–10.

Yan X, Duan H, Ni Y, Zhou Y, Wang X, Qi H, Gong L, Liu H, Tian F, Lu Q, et al. Tislelizumab combined with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy for surgically resectable esophageal cancer: A prospective, single-arm, phase II study (TD-NICE). Int J Surg. 2022;103:106680.

Al-Kaabi A, van der Post RS, van der Werf LR, Wijnhoven BPL, Rosman C, Hulshof M, van Laarhoven HWM, Verhoeven RHA, Siersema PD. Impact of pathological tumor response after CROSS neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery on long-term outcome of esophageal cancer: a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(4):497–504.

Chevrollier GS, Giugliano DN, Palazzo F, Keith SW, Rosato EL, Evans Iii NR, Berger AC. Patients with Non-response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation for Esophageal Cancer Have No Survival Advantage over Patients Undergoing Primary Esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(2):288–98.

Lin JW, Hsu CP, Yeh HL, Chuang CY, Lin CH. The impact of pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus. J Chin Med Assoc. 2018;81(1):18–24.

Liu J, Yang Y, Liu Z, Fu X, Cai X, Li H, Zhu L, Shen Y, Zhang H, Sun Y, et al. Multicenter, single-arm, phase II trial of camrelizumab and chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2022; 10(3):e004291.

Yang W, Xing X, Yeung SJ, Wang S, Chen W, Bao Y, Wang F, Feng S, Peng F, Wang X, et al. Neoadjuvant programmed cell death 1 blockade combined with chemotherapy for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(1):e003497.

Gibney GT, Weiner LM, Atkins MB. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):e542–51.

Jiao R, Luo H, Xu W, Ge H. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: progress and opportunities. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:6023–32.

Yuan J, Hegde PS, Clynes R, Foukas PG, Harari A, Kleen TO, Kvistborg P, Maccalli C, Maecker HT, Page DB, et al. Novel technologies and emerging biomarkers for personalized cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:3.

Li N, Gao L, Ge Y, Zhao L, Bai C, Wang Y. Prognostic and predictive significance of circulating biomarkers in patients with advanced upper gastrointestinal cancer undergoing systemic chemotherapy. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1195848.

Beig N, Khorrami M, Alilou M, Prasanna P, Braman N, Orooji M, Rakshit S, Bera K, Rajiah P, Ginsberg J, et al. Perinodular and Intranodular Radiomic Features on Lung CT Images Distinguish Adenocarcinomas from Granulomas. Radiology. 2019;290(3):783–92.

Lu N, Zhang WJ, Dong L, Chen JY, Zhu YL, Zhang SH, Fu JH, Yin SH, Li ZC, Xie CM. Dual-region radiomics signature: Integrating primary tumor and lymph node computed tomography features improves survival prediction in esophageal squamous cell cancer. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;208:106287.

Sun Z, Jiang Y, Chen C, Zheng H, Huang W, Xu B, Tang W, Yuan Q, Zhou K, Liang X, et al. Radiomics signature based on computed tomography images for the preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis at individual stations in gastric cancer: A multicenter study. Radiother Oncol. 2021;165:179–90.

Hu Y, Xie C, Yang H, Ho JWK, Wen J, Han L, Lam KO, Wong IYH, Law SYK, Chiu KWH, et al. Computed tomography-based deep-learning prediction of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy treatment response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2021;154:6–13.

Li J, Xu S, Wang Y, Fang M, Ma F, Xu C, Li H. Spectral CT-based nomogram for preoperative prediction of perineural invasion in locally advanced gastric cancer: a prospective study. Eur Radiol. 2023;33(7):5172–83.

Yang J, Xue R, Wu J, Jia L, Li J, Yu H, Zhu Y, Dong J, Meng Q. Development and Validation of a Nomogram for 90-day Outcome in Patients with Hepatitis B Virus-related Acute-on-chronic Liver Failure. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10(3):458–66.

Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research. 2002;16(1):321–57.

Wang Z, Shao C, Wang Y, Duan H, Pan M, Zhao J, Wang J, Ma Z, Li X, Yan X. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in surgically resectable esophageal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2022;104:106767.

Zhu J, Leng X, Gao B, Wang B, Zhang H, Wu L, Ma J, Tan Y, Peng L, Han Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in resectable esophageal or gastroesophageal junction carcinoma: A pooled analysis of prospective clinical trials. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1041233.

Huang J, Xu J, Chen Y, Zhuang W, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Chen J, Zhang H, Niu Z, Fan Q, et al. Camrelizumab versus investigator’s choice of chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCORT): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):832–42.

Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, Mao T, Wang J, Fan Q, Zhang Y, Zhao K, Chen Z, Gao S, et al. Effect of Camrelizumab vs Placebo Added to Chemotherapy on Survival and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The ESCORT-1st Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326(10):916–25.

Lu Z, Wang J, Shu Y, Liu L, Kong L, Yang L, Wang B, Sun G, Ji Y, Cao G, et al. Sintilimab versus placebo in combination with chemotherapy as first line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ORIENT-15): multicentre, randomised, double blind, phase 3 trial. BMJ. 2022;377:e068714.

Chen X, Xu X, Wang D, Liu J, Sun J, Lu M, Wang R, Hui B, Li X, Zhou C, et al. Neoadjuvant sintilimab and chemotherapy in patients with potentially resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (KEEP-G 03): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(2):e005830.

Liu J, Li J, Lin W, Shao D, Depypere L, Zhang Z, Li Z, Cui F, Du Z, Zeng Y, et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab plus chemotherapy for resectable, locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (NIC-ESCC2019): A multicenter, phase 2 study. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(1):128–37.

Yang Z, He B, Zhuang X, Gao X, Wang D, Li M, Lin Z, Luo R. CT-based radiomic signatures for prediction of pathologic complete response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Radiat Res. 2019;60(4):538–45.

Bi WL, Hosny A, Schabath MB, Giger ML, Birkbak NJ, Mehrtash A, Allison T, Arnaout O, Abbosh C, Dunn IF, et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: Clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(2):127–57.

Liu C, Zhao W, Xie J, Lin H, Hu X, Li C, Shang Y, Wang Y, Jiang Y, Ding M, et al. Development and validation of a radiomics-based nomogram for predicting a major pathological response to neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy for patients with potentially resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1115291.

Liang Z, Huang A, Wang L, Bi J, Kuang B, Xiao Y, Yu D, Hong M, Zhang T. A radiomics model predicts the response of patients with advanced gastric cancer to PD-1 inhibitor treatment. Aging (Albany NY). 2022;14(2):907–22.

Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, Weiss K, Kelly DW, Adusumilli PS, Paik PK, Plitas G, Ladanyi M, Postow MA, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):729.

Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. 2018;32(19–20):1267–84.

Shaul ME, Fridlender ZG. Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(10):601–20.

Gooden MJ, de Bock GH, Leffers N, Daemen T, Nijman HW. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):93–103.

Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao J, Zhang S, Basar R, Thakur R, Yizhak K, Sade-Feldman M, Blando J, Han G, et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020;577(7791):549–55.

Hoffmann TK, Dworacki G, Tsukihiro T, Meidenbauer N, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. Spontaneous apoptosis of circulating T lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer and its clinical importance. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(8):2553–62.

Rocha NP, Fortes RC. Total lymphocyte count and serum albumin as predictors of nutritional risk in surgical patients. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28(3):193–6.

Wu Y, Wu H, Lin M, Liu T, Li J. Factors associated with immunotherapy respond and survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl Oncol. 2022;15(1):101268.

Perrone F, Favari E, Maglietta G, Verzè M, Pluchino M, Minari R, Sabato R, Mazzaschi G, Ronca A, Rossi A, et al. The role of blood cholesterol quality in patients with advanced cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72(7):2127–35.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by Shandong Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2022QH121 and No. ZR2022ZD31) and Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2021LCZX04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. YY: Data curation, Writing-review & editing. ZTW: Writing-review & editing, Resources. SSL: Supervision, Validation. BZ: Data curation, Writing-review & editing. ZS: Data curation. LLZ: Data curation. QC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources. BSL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing-review & editing, Resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the IRB of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute (approval number: SDTHEC2023001010), and the IRB waived the need for informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Yi, Y., Wang, Z. et al. A combined nomogram based on radiomics and hematology to predict the pathological complete response of neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 24, 460 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12239-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12239-0