Abstract

Background

Genetic screening for pathogenic variants (PVs) in cancer predisposition genes can affect treatment strategies, risk prediction and preventive measures for patients and families. For decades, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) has been attributed to PVs in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, and more recently other rare alleles have been firmly established as associated with a high or moderate increased risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer. Here, we assess the genetic variation and tumor characteristics in a large cohort of women with suspected HBOC in a clinical oncogenetic setting.

Methods

Women with suspected HBOC referred from all oncogenetic clinics in Sweden over a six-year inclusion period were screened for PVs in 13 clinically relevant genes. The genetic outcome was compared with tumor characteristics and other clinical data collected from national cancer registries and hospital records.

Results

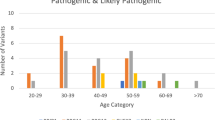

In 4622 women with breast and/or ovarian cancer the overall diagnostic yield (the proportion of women carrying at least one PV) was 16.6%. BRCA1/2 PVs were found in 8.9% of women (BRCA1 5.95% and BRCA2 2.94%) and PVs in the other breast and ovarian cancer predisposition genes in 8.2%: ATM (1.58%), BARD1 (0.45%), BRIP1 (0.43%), CDH1 (0.11%), CHEK2 (3.46%), PALB2 (0.84%), PTEN (0.02%), RAD51C (0.54%), RAD51D (0.15%), STK11 (0) and TP53 (0.56%). Thus, inclusion of the 11 genes in addition to BRCA1/2 increased diagnostic yield by 7.7%. The yield was, as expected, significantly higher in certain subgroups such as younger patients, medullary breast cancer, higher Nottingham Histologic Grade, ER-negative breast cancer, triple-negative breast cancer and high grade serous ovarian cancer. Age and tumor subtype distributions differed substantially depending on genetic finding.

Conclusions

This study contributes to understanding the clinical and genetic landscape of breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility. Extending clinical genetic screening from BRCA1 and BRCA2 to 13 established cancer predisposition genes almost doubles the diagnostic yield, which has implications for genetic counseling and clinical guidelines. The very low yield in the syndrome genes CDH1, PTEN and STK11 questions the usefulness of including these genes on routine gene panels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the past thirty years, genetic testing for inherited pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in patients with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) has moved from research to being an established part of breast and ovarian cancer care. With studies demonstrating high cumulative cancer risks in affected women [1] and improved disease-specific and overall survival after risk-reducing surgery [2,3,4] the number of referrals for genetic analysis has steadily increased. Additionally, BRCA1/2 status has clinical value as a treatment predictive marker, both for platinum-containing chemotherapy and for poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) [5,6,7,8].

While mainstream testing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 has entered clinical care, it has become clear that the majority of women with presumed HBOC do not carry a pathogenic variant in either of these genes. The search for “BRCA3” has led to the conclusion that no gene with a similar population frequency of pathogenic variants and associated breast and ovarian cancer risk as BRCA1 or BRCA2 exists. Rather, the genetic landscape of predisposition to common cancers consists of very rare high-risk alleles in combination with common low-risk alleles (typically single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) and an intermediate group of rare moderate-risk alleles [9]. Moderate-penetrance genes are defined as genes with risk alleles associated with odds ratio > 2 but ≤ 4 for risk of developing breast cancer, and high-penetrance as genes with risk alleles associated with odds ratio > 4 [10]. From an oncogenetic perspective, these groups all pose challenges for risk prediction and genetic counseling. Very rare syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53), Cowden/PTEN hamartoma syndrome (PTEN), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11) and hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and lobular breast cancer (CDH1) are all considered to be associated with high breast cancer risks [11], but due to the rarity of pathogenic variants and ascertainment bias in published studies, risk estimates are uncertain. The common SNPs are associated with too low cancer risks to be useful as individual markers in the clinical setting, but the combination of many such alleles into a polygenic risk score (PRS) has shown promise for cancer risk prediction both in the general population and as modifiers for carriers of high-risk variants [12,13,14,15,16].

Many candidate genes have been proposed to be associated with a moderate increased breast cancer risk, and with the introduction of the next generation sequencing (NGS) technology, several commercial laboratories began offering broad gene panels including genes with poorly defined risk. In 2012, the Swedish BRCA1 and BRCA2 study collaborators formed a national study named SWEA (The Swe-BRCA Extended Analysis) and designed a gene panel targeting 63 genes for use in the study. Established breast and/or ovarian cancer genes were included, at the time mainly BRCA1, BRCA2 and a few syndrome genes, but also a long list of candidate genes for which rare alleles could potentially be associated with increased risk of developing breast cancer based on, for example, their functional role or published associations. Only pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in established risk genes were reported back to the clinicians.

Only recently has the question of moderate-penetrance breast cancer risk genes largely been settled. In two large case–control studies published in 2021, a significant association with breast cancer was shown for protein truncating variants (PTVs) in ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C and RAD51D. Pathogenic variants in TP53 only showed a significant association in the BRIDGES study [17], CDH1 was associated only with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer in the CARRIERS study [18], PTEN failed to show significant association in either study and STK11 was not associated with breast cancer in the BRIDGES study. These results illustrate the challenge to define risks for the very rare syndrome genes even in large case–control studies.

BRIP1 is not established as a risk factor of clinical relevance for breast cancer but has previously been shown to be associated with a moderate increased risk for ovarian cancer [19,20,21].

In this article, we report our findings of pathogenic variants in the 13 established cancer predisposition genes ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11 and TP53 in a nation-wide cohort of over 4600 women with breast- and/or ovarian cancer. We also correlate the genetic findings with clinically relevant parameters such as age at diagnosis, tumor location, histopathological and molecular subtypes.

Methods

Healthcare setting

Assessment, counseling, and genetic testing for hereditary cancer is centralized to oncogenetic clinics at the six healthcare regions with university hospitals in Sweden. This service is reimbursed by the public health care system and accessible to all citizens on a national level. Patients with suspected hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer fulfilling national criteria for genetic analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Additional file 1: HBOC genetic testing criteria in Sweden 2012–2018) were offered genetic testing. For the duration of this research study, clinical testing was centralized to one laboratory serving all healthcare regions (BRCAlab, Lund University, Lund, Sweden).

Study cohort

The nation-wide SWEA study was open for inclusion between April 2012 and April 2018. Patients 18 years or older who were able to understand the written study information and where genetic screening of BRCA1 and BRCA2 was clinically indicated were offered inclusion in the study.

Genetic analysis

All laboratory analyses were performed at the BRCAlab at the Department of Clinical Sciences at Lund University, Lund, Sweden. Targeted sequencing libraries were prepared from germline DNA extracted from blood using an Agilent SureSelectXT custom hybrid selection assay. The assay targeted 63 genes, including the 13 established cancer susceptibility genes that were the focus of this study (Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods). Apart from repetitive and low complexity genomic regions that are difficult to capture efficiently, the complete gene region of the 13 genes were captured by the assay, including introns and up- and downstream regions (Additional file 2: Table S9). Libraries were paired-end sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 or 2500 system to a target average sequence depth of 400–500 × over the targeted region. Sequences were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37) and genetic variants, including larger structural variants, were identified using a combination of variant calling tools. Variant calling was tuned for sensitivity and all variants classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic in the 13 genes were confirmed using Sanger sequencing to identify potential false positives and safeguard accuracy. If any sample had below 30 × sequence coverage for any genomic position within coding exons and 20 base pairs of adjacent introns, that region was also Sanger sequenced to ensure complete coverage of all genes for all samples. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were also analyzed in all samples using Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA), to confirm deletions and duplications of one or more exons. For details about library preparation, sequencing, alignment, variant calling, confirmatory Sanger sequencing, MLPA and variant classification, see Additional File 1: Supplementary Methods. For the entire study duration, regular national tumor board sessions were organized to discuss difficult cases and to reach agreements on variant classification and inclusion of additional clinical grade genes as evidence emerged.

If not specified, variants classified as pathogenic (class 5) or likely pathogenic (class 4) are collectively named pathogenic variants (PVs) in the Results and Discussion.

Clinical parameters

For all patients where genetic analysis was performed, data on cancer diagnoses (e.g., age at diagnosis, histopathology, and localization) was collected from the referring oncogenetic clinics. This information was later confirmed using data from the cancer registry at the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, where all cancer diagnoses since 1958 are registered. We also included tumor-specific data from national quality registries for ovarian and breast cancer with coverage since 2008. Overall, there was a high level of consistency between the three data sources, and remaining discrepancies were manually assessed and curated by one of the authors (HE).

Morphology and biomarker data was derived from quality registers and pathology reports. For breast cancer, the definition of estrogen and progesterone receptor positivity (ER + , PR +) was ≥ 10% positive tumor cells detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC). HER2 status was determined based on IHC first, and in case of a 2 + IHC score followed by in-situ hybridization [22]. When defining breast cancer molecular subtypes, we assigned subtypes according to current Swedish national breast cancer guidelines, but the ER + , HER2-, Nottingham Histologic Grade 2 (NHG 2) subgroup was not further divided into Luminal A-like/B-like due to lack of consistent high-quality data for Ki67 [23].

Statistical analysis

To analyze the association between categorical variables, the Pearson chi-square test (two-tailed) was used. All analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS statistical computing package (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). In the gene specific tables in Additional file 2, patients with one or two pathogenic variants in the same gene were not distinguished since it was not always possible to determine monoallelic or biallelic status. In case of bilateral breast cancer, each cancer was analyzed as an independent event.

Results

Study cohort

In total, blood samples from 4762 consenting individuals (97.8% women) with suspected HBOC were analyzed. Based on regional data at collaborating oncogenetic clinics and log files from BRCAlab, we estimate that these individuals represent about 85% of all patients screened for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Sweden during the study period. Three women withdrew their consent after genetic analysis. Women without breast or ovarian cancer and men were not included in the main analysis, leaving a cohort of 4622 women with confirmed breast and/or ovarian cancer (Fig. 1). Of these, 4013 women had breast cancer only, 390 had ovarian cancer only, and 219 women had both breast and ovarian cancer. The median age for first breast cancer diagnosis was 45 years (range 21–87 years) and for ovarian cancer 57 years (range 20–90 years).

Characteristics and classification of genetic variants

In this study we report 316 unique variants as pathogenic (n = 281) or likely pathogenic (n = 35) (Additional file 2: Table S1). Frameshift, nonsense, and canonical splice site variants predicted to cause loss-of-function, through nonsense mediated decay or disruption of critical protein functional regions, were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. The pathogenicity of other variants was judged based on available evidence, such as amino acid conservation and biophysical properties, population allele frequencies and functional assays. Prior classifications and evidence of pathogenicity from the NIH-NCBI ClinVar archive (final accession 26 August 2022) and other databases and literature were considered. For BRCA1 and BRCA2, we used the criteria defined by the Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles (ENIGMA; enigmaconsortium.org). The effect of variants predicted to alter splicing outside the canonical ± 1,2 positions was confirmed using cDNA sequencing and minigene assays (Additional file 2: Table S2). Due to uncertainty in the level of risk associated with missense variants in the moderate penetrance genes (ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CHEK2, RAD51C and RAD51D), missense variants in these genes were not reported in this study.

No clinically relevant variants were detected in STK11. For the other genes, 32 large structural variants were detected (10.1% of all reported variants), and the other PTVs were classified as frameshift (142), stop gained (74) or as affecting splicing (46). Additionally, in BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53, 22 rare pathogenic and likely pathogenic missense variants were found. Out of the 316 variants, we classified 261 in concordance with previous ClinVar entries, and 52 variants were not found in ClinVar (Additional file 2: Table S1). The remaining 3 variants were missense variants in TP53 with a status as variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in ClinVar. However, we have classified them as likely pathogenic (for further details, see Additional file 1: Discordant classification justification). The classification of all 316 variants has been submitted to ClinVar.

In total, 816 occurrences of the 316 unique PVs were reported in the entire study cohort (4759 individuals, Fig. 1). The frequency of PVs was skewed, where 215 unique variants (68.0%) were only identified once. On the other hand, some variants were commonly seen, with CHEK2 c.1100del, p.(Thr367Metfs*15) being the single most frequent PV, reported in 142 individuals. 9 other variants were reported in 10 or more patients. Out of these, 7 were BRCA1 variants known to be common in the Swedish population. The 2 remaining variants were RAD51C c.93del, p.(Phe32Serfs*8) and BARD1 c.1690C > T, p.(Gln564*), seen in 13 and 11 individuals, respectively (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Six hundred sixty-nine (82.0%) of all detected PVs were found in the genes BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2 and ATM, see Fig. 2 for visualization of these PVs in “lolliplot” graphs. Lolliplots for the other genes are depicted in Additional file 3: Fig. S1.

Lollipop plots showing the location and frequency of PVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2 and ATM. The gene model at the bottom of each plot shows exons in alternating shades of gray with untranslated regions thinner. Gene domains or other regions of interest are shown in colors defined by the legend below each gene model. The gene domain or region abbreviations are explained with references in Additional file 2: Table S6. The x-axis shows amino acid residue numbering according to the selected RefSeq protein for each gene. The number of carriers for each unique variant is indicated by the height and size of each lollipop and the inscribed number in the marker. The shape, color and location of the lollipops show the type of variant with structural variants below the gene model (red circle: large deletion, dark blue square: large duplication, green diamond: alu insertion) and other variants above (orange circle: frameshift, cyan circle: stop gain, pale yellow square: missense, purple diamond: intronic or synonymous splice variants, pale green diamond: exonic missense splice variant). Lollipops for variants in introns are placed at the border between adjacent exons. The horizontal bars above the gene model indicate the extent of large deletions (red) and large duplications (dark blue). All structural variants are labeled with a short form alias (the corresponding HGVS descriptions can be found in Additional file 2: Table S1) and the more common of the other variants are labeled with HGVS descriptions. Corresponding lollipop plots for BARD1, BRIP1, CDH1, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D and TP53 are shown in Additional file 3: Fig. S1

Detailed assessment of variants in TP53

Evaluation of variants in TP53 comes with some specific challenges (see Discussion). In this study, PVs in TP53 were detected in 27 individuals, 1 man and 26 women. As detailed in Additional file 2: Table S3, segregation analysis in the families could confirm that the TP53 variant was of germline origin in 14 individuals including the only man. In 4 women, the recurrent variant TP53 c.542G > A, p.(Arg181His) was detected at near heterozygote variant allele frequency (VAF), consistent with probable germline origin. In our data, the 99% confidence interval for VAF for heterozygous carriers of variants of known germline origin was 40.1% to 59.9%. We therefore consider VAF within this range as consistent with a germline origin for heterozygous variants. Another group of 4 women had a personal and/or family history suggesting a probable germline variant, leaving 5 women with details either suggesting clonal hematopoiesis or uncertainty on the germline or somatic origin of the identified PV in TP53. One of these women had two concurrent PVs in TP53 with a variant allele frequency at 29%, consistent with clonal hematopoiesis or somatic mosaicism.

Individuals not included in the main analysis

Seventy-four participating men had breast cancer only, 18 had prostate cancer only, and 5 men had both breast and prostate cancer. PVs were detected in 17 of these men (17.5%), 2 in BRCA1, 8 in BRCA2, 3 in ATM, 3 in CHEK2 and 1 in TP53. Thirty-two women and 8 men did not have a personal history of cancer motivating genetic testing, but typically were tested as presumed obligate carriers. Among these 40 individuals, three (7.5%) were heterozygous carriers of a PV in BRCA1.

Diagnostic yield in women with breast and/or ovarian cancer

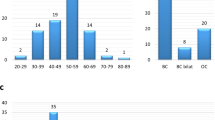

Seven hundred sixty-five of the 4622 women with breast and/or ovarian cancer carried at least one PV, for an overall diagnostic yield of 16.6%. As shown in Table 1, the group of women with both breast and ovarian cancer had the highest diagnostic yield (70/219, 32.0%), the ovarian cancer only group had a yield of 23.8% (93/390), and the lowest yield was seen in the breast cancer only group, 15.0% (602/4013).

The yield for BRCA1 and BRCA2 combined was 8.9%; 275 (5.95%) BRCA1 and 136 (2.94) BRCA2 carriers (Additional file 2: Table S4a). Very few variants were detected in the rare syndrome genes CDH1 (0.11%, 5 carriers), PTEN (0.02%, 1 carrier) and STK11 (no carriers detected in the entire cohort). PVs in TP53 and PALB2 were found in 26 (0.56%) and 39 (0.84%) women, respectively. For moderate penetrance genes, the highest yield was found in CHEK2 with 160 (3.46%) carriers. Finally, 73 (1.58%) women had a PV in ATM, 21 (0.45%) in BARD1, 20 (0.43%) in BRIP1, 25 (0.54%) in RAD51C and 7 (0.15%) in RAD51D.

Most carriers had only one heterozygous PV, but 29 of the 765 women (3.8%) were identified as carriers of two different variants, and one woman carried three variants. Twenty-three of these women had variants in two different genes, whereas 7 women carried two variants in CHEK2 (Additional file 2: Table S5). Interestingly, 6 of the 7 women with two CHEK2 variants had bilateral breast cancer. Segregation analyses in the families could confirm that three of these women carried the CHEK2 variants in trans, but for the remaining four women this information is lacking.

Genetic findings in breast and ovarian cancer subgroups

The overall diagnostic yield of PVs in any investigated gene per subgroup of women is shown in Table 1 and per subgroup of breast cancer in Table 2. The corresponding yield per gene is displayed in Additional file 2: Table S4a and S4b.

The diagnostic yield was higher in women with younger age at breast cancer diagnosis and bilateral breast cancer (Table 1). A high yield was also seen in breast cancer cases with higher NHG grade and in the correlated subgroups medullary breast cancer, ER-negative breast cancer and triple-negative breast cancer (Table 2). As is evident from the gene-specific tables (Additional file 2: Table S4a and S4b) this result is largely driven by BRCA1.

In women with ovarian cancer, age at diagnosis and morphological subtype correlated with diagnostic yield (Table 1). As seen in the gene-specific table (Additional file 2: Table S4a), BRCA1 PVs were most common in the age interval 50–59 years, whereas the highest frequency of BRCA2 variants was seen at the age interval 60–69 years. The high diagnostic yield in women with high grade serous (HGS) morphological subtype was primarily due to PVs in BRCA1.

Discussion

In this study, we report the results of genetic testing and clinical characterization of 4622 women with breast and/or ovarian cancer, referred for suspected HBOC. We found that 765 (16.6%) had at least one PV in any of the 13 genes that have solid evidence for a high or moderate increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer: ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11 and TP53 [17, 18, 24]. It should be noted that except for TP53, we detected very few PVs in the known rare syndrome genes CDH1 (n = 5), PTEN (n = 1) and STK11 (n = 0).

All oncogenetic clinics in Sweden participated in the study, and we estimate that this cohort represents about 85% of all women screened for PVs in HBOC-related genes in Sweden over the six-year inclusion period (2012–2018).

The clinical criteria for offering analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 during the study period were designed to roughly lead to a 10% diagnostic yield, and in accordance with that we found that 8.9% of the women had a PV in either of these two genes. In the other 11 genes, clinically relevant variants were detected in 8.2% of women, but since some carried more than one variant, the overall yield per woman was 16.6%. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the overall yield was significantly higher in certain subgroups, e.g., women with both breast and ovarian cancer, women with high grade serous ovarian cancer, women with triple-negative breast cancer, or women with breast cancer at a younger age. At the same time, a reasonably high yield of 12.1% was seen even in the oldest subgroup of women with a breast cancer diagnosis at age 70 or older. Since most of the women are expected to have a family history for the disease (see “Genetic testing criteria” in Additional file 1), these figures are not generalizable to an unselected breast cancer population.

Recently, a follow-up of the BRIDGES breast cancer case–control study was published, where the molecular subtypes of tumors associated with 9 breast cancer predisposition genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D and TP53) were reported [25]. While the numbers are relatively small in our study, it is interesting to note that the distribution of breast cancer molecular subtypes per gene (Additional file 2: Table S4b) shows a similar pattern as the association odds ratios presented in the BRIDGES follow-up study. In fact, for all 9 genes, the results between the two studies are completely consistent for the molecular subtypes with the highest mutation frequency per gene: PVs in BARD1, BRCA1, RAD51C and RAD51D were most common in triple-negative breast cancer, ATM, BRCA2 and PALB2 were enriched in the Luminal B-like subtype (ER + , HER2-, NHG 3), CHEK2 was most frequently mutated in the ER + , HER2 + subtype, and TP53 was enriched in HER2 + subtypes.

We identified 316 unique PVs. Most variant classifications were either concordant with existing ClinVar entries or PTVs that could easily be classified. For some variants we have performed additional analyses to clarify pathogenicity. Eighteen variants outside of canonical splice positions were shown to affect splicing (Additional file 2: Table S2). As an example, PALB2 c.47A > C, p.(Lys16Thr) is a missense variant located in the last codon of exon 1 in PALB2, not previously reported to ClinVar. cDNA-analyses could confirm that the variant introduces a cryptic splice site, yielding a frameshift and a premature stop codon. We disagreed with ClinVar classifications on 3 missense variants in TP53 (Additional file 1: Discordant classification justification), e.g., TP53 c.328C > T, p.(Arg110Cys) has been reported on several occasions as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in ClinVar but was classified as likely pathogenic by us, partly based on functional characterization performed in another Swedish study [26].

Apart from missense variants that affect splicing, we only reported missense variants in the genes BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53. Especially for genes associated with a moderate increased risk for breast cancer, several reports show that missense variants as a group are associated with lower breast cancer risks than protein truncating variants in the same genes. For such missense variants, clinical utility is currently limited. One well-described example is CHEK2 c.470 T > C, p.(Ile157Thr) that was identified multiple times in our study, but not reported due to its lower penetrance [17, 27]. It should be noted that there are exceptions to this rule, for instance the variant ATM c.7271 T > G, p.(Val2424Gly) acts in a dominant negative fashion and has been associated with higher risks than PTVs in the same gene [28,29,30]. ATM c.7271 T > G has a particularly high prevalence in Australia and was not identified in our study cohort.

In total, we detected 816 PVs in the entire cohort, and some variants were recurrent (Fig. 2, Additional file 3: Fig. S1, Additional file 2: Table S1). The most commonly detected PV was CHEK2 c.1100del, p.(Thr367Metfs*15) that was seen 142 times, representing 83.5% of reported CHEK2 variants or 17.4% of all variants. CHEK2 was also the gene with the second highest frequency of PVs after BRCA1 (Additional file 2: Table S4a). No individual had two PVs in BRCA1, consistent with the notion that except for cases with hypomorphic alleles, biallelic inherited loss of function of BRCA1 is not compatible with survival [31,32,33]. On the other hand, CHEK2 was the only gene in our study in which we did find double heterozygous variants (Additional file 2: Table S5). Biallelic loss of CHEK2 has been associated with significantly higher breast cancer risks than heterozygote carriership in earlier studies [34, 35], and indeed, bilateral breast cancer was seen in six out of the 7 women with two PVs in CHEK2.

The assessment of variants in TP53 is particularly challenging, since PVs in this gene have been shown to occur de novo including germline mosaicism [36] at a higher frequency than for other cancer predisposition genes, but it has also been demonstrated that such variants may have been acquired somatically in a process termed clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) [37]. In Additional file 2: Table S3, we report our assessment of the 27 TP53 carriers in this study, where we argue that it is likely that the majority carried a germline PV. A few cases were more uncertain, especially since recent findings suggest that even when the variant allele frequency is consistent with a heterozygous variant, a substantial proportion may be due to CHIP [38]. A special case was the only woman in this study who carried three variants, a heterozygous PV in PALB2 and two TP53-variants at 29% VAF, strongly suggesting a somatic origin for both variants in TP53 (Additional file 2: Table S3). Going forward, it may be advisable to analyze a follow-up skin biopsy for all patients with a presumed germline TP53 PV detected in blood or saliva where segregation analysis in the family is uninformative.

Data sharing is important to improve genetic diagnostics, and we have submitted all classified pathogenic variants to ClinVar. Furthermore, we have shared data in international collaborations aiming to better define the risk associated with PVs in cancer predisposition genes. Through modified segregation analysis including families from this study, risk estimates for breast and ovarian cancer have been refined for PTVs in RAD51C, RAD51D [39], PALB2 [40] and for the moderate penetrance missense variant BRCA1 c. 5096G > A, p.(Arg1699Gln) (R1699Q) [41].

The strengths of this study include a large sample with nation-wide coverage, representative of clinical oncogenetic testing for suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancer over several years. We achieved this by setting up a pragmatic study within the existing national oncogenetic network, in which all six participating clinics work in close collaboration. Hence, all patients fulfilling clinical criteria for routine genetic testing could be invited to the study. The centralized analyses at a national laboratory ensured quality and consistency in technical procedures and variant interpretation. Another strength is the detailed clinico-pathological annotation of cancer diagnoses from national registries, which have been shown to have a high degree of completeness [42,43,44]. With a study design where many candidate genes were sequenced but only validated clinically relevant variants were reported back (also retrospectively), we have avoided misinterpretation in the clinical setting of genetic variants that were considered interesting candidates a few years ago but now have been disputed, such as RECQL and NBN [17, 18].

The study has some limitations. First, while the cohort is representative for oncogenetic clinics, the results cannot be extrapolated to unselected cancer cases or a healthy population. Second, even though there were national clinical criteria for when to offer analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2, we do not have detailed information on referral reasons for every single included individual. Third, we have not collected any data on ethnicity, preventing such subgroup analyses. Also, for the question of ovarian cancer predisposition it is a clear limitation that the genes for Lynch syndrome (EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) were not included on the gene panel.

Conclusions

The SWEA study contributes to an increased understanding of the genetic landscape of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Our results show that the addition of confirmed predisposition genes for breast and ovarian cancer almost doubles the diagnostic yield as compared with testing only for BRCA1 and BRCA2. The preliminary results of this study have already informed national guidelines for cancer care. In the current Swedish national breast cancer guidelines [22] the syndrome genes with a very low frequency of findings (CDH1, PTEN, STK11) have been excluded from the routine clinical gene panel. All other genes reported in this article except BRIP1 are now recommended for assessment of suspected hereditary breast cancer. BRIP1 is instead included on the corresponding gene panel for ovarian cancer predisposition, together with BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D and the Lynch syndrome genes [45].

Availability of data and materials

All 316 pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants identified in this study, together with justification for classification in ambiguous cases, are available in the Additional files. The variant classifications have also been submitted to the database ClinVar. Datasets on clinical parameters and tumor characteristics are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CHIP:

-

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential

- ENIGMA:

-

Evidence-based network for the interpretation of germline mutant alleles

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- HBOC:

-

Hereditary breast and ovarian Cancer

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- MLPA:

-

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- NHG:

-

Nottingham histologic grade

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- PARPi:

-

Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase inhibitors

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- PRS:

-

Polygenic risk score

- PV:

-

Pathogenic variant

- PTV:

-

Protein truncating variant

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- Swe-BRCA:

-

The Swedish BRCA1 and BRCA2 study collaborators

- SWEA:

-

The Swe-BRCA extended analysis study

- VUS:

-

Variant of uncertain significance

References

Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips KA, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom MJ, et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2402–16.

Li X, You R, Wang X, Liu C, Xu Z, Zhou J, et al. Effectiveness of Prophylactic Surgeries in BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3971–81.

Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, Singer CF, Karlan B, Senter L, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–53.

Ludwig KK, Neuner J, Butler A, Geurts JL, Kong AL. Risk reduction and survival benefit of prophylactic surgery in BRCA mutation carriers, a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2016;212(4):660–9.

Loibl S, O’Shaughnessy J, Untch M, Sikov WM, Rugo HS, McKee MD, et al. Addition of the PARP inhibitor veliparib plus carboplatin or carboplatin alone to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (BrighTNess): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(4):497–509.

Diéras V, Han HS, Kaufman B, Wildiers H, Friedlander M, Ayoub JP, et al. Veliparib with carboplatin and paclitaxel in BRCA-mutated advanced breast cancer (BROCADE3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(10):1269–82.

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2495–505.

Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, Viale G, Fumagalli D, Rastogi P, et al. Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-Mutated Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394–405.

Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2143–53.

Easton DF, Pharoah PD, Antoniou AC, Tischkowitz M, Tavtigian SV, Nathanson KL, et al. Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2243–57.

Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 3.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2023. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf.

Lee A, Mavaddat N, Wilcox AN, Cunningham AP, Carver T, Hartley S, et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet Med. 2019;21(8):1708–18.

Barnes DR, Rookus MA, McGuffog L, Leslie G, Mooij TM, Dennis J, et al. Polygenic risk scores and breast and epithelial ovarian cancer risks for carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. Genet Med. 2020;22(10):1653–66.

Hughes E, Wagner S, Pruss D, Bernhisel R, Probst B, Abkevich V, et al. Development and Validation of a Breast Cancer Polygenic Risk Score on the Basis of Genetic Ancestry Composition. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6: e2200084.

Pal Choudhury P, Brook MN, Hurson AN, Lee A, Mulder CV, Coulson P, et al. Comparative validation of the BOADICEA and Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk models incorporating classical risk factors and polygenic risk in a population-based prospective cohort of women of European ancestry. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):22.

Hughes E, Tshiaba P, Wagner S, Judkins T, Rosenthal E, Roa B, et al. Integrating Clinical and Polygenic Factors to Predict Breast Cancer Risk in Women Undergoing Genetic Testing. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5.

Dorling L, Carvalho S, Allen J, González-Neira A, Luccarini C, Wahlström C, et al. Breast Cancer Risk Genes - Association Analysis in More than 113,000 Women. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):428–39.

Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, Huang H, Lee KY, Na J, et al. A Population-Based Study of Genes Previously Implicated in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):440–51.

Rafnar T, Gudbjartsson DF, Sulem P, Jonasdottir A, Sigurdsson A, Jonasdottir A, et al. Mutations in BRIP1 confer high risk of ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1104–7.

Ramus SJ, Song H, Dicks E, Tyrer JP, Rosenthal AN, Intermaggio MP, et al. Germline Mutations in the BRIP1, BARD1, PALB2, and NBN Genes in Women With Ovarian Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(11).

Domchek SM, Robson ME. Update on Genetic Testing in Gynecologic Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(27):2501–9.

National clinical breast cancer care guideline; version: 4.1. Confederation of Regional Cancer Centres in Sweden. 2022. Available from: https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/brostcancer/vardprogram/.

Acs B, Fredriksson I, Rönnlund C, Hagerling C, Ehinger A, Kovács A, et al. Variability in Breast Cancer Biomarker Assessment and the Effect on Oncological Treatment Decisions: A Nationwide 5-Year Population-Based Study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(5).

Foulkes WD. The ten genes for breast (and ovarian) cancer susceptibility. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):259–60.

Breast Cancer Association C, Mavaddat N, Dorling L, Carvalho S, Allen J, Gonzalez-Neira A, et al. Pathology of Tumors Associated With Pathogenic Germline Variants in 9 Breast Cancer Susceptibility Genes. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(3):e216744.

Kharaziha P, Ceder S, Axell O, Krall M, Fotouhi O, Böhm S, et al. Functional characterization of novel germline TP53 variants in Swedish families. Clin Genet. 2019;96(3):216–25.

Liu C, Wang Y, Wang QS, Wang YJ. The CHEK2 I157T variant and breast cancer susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(4):1355–60.

Southey MC, Goldgar DE, Winqvist R, Pylkäs K, Couch F, Tischkowitz M, et al. PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM rare variants and cancer risk: data from COGS. J Med Genet. 2016;53(12):800–11.

van Os NJ, Roeleveld N, Weemaes CM, Jongmans MC, Janssens GO, Taylor AM, et al. Health risks for ataxia-telangiectasia mutated heterozygotes: a systematic review, meta-analysis and evidence-based guideline. Clin Genet. 2016;90(2):105–17.

Bernstein JL, Teraoka S, Southey MC, Jenkins MA, Andrulis IL, Knight JA, et al. Population-based estimates of breast cancer risks associated with ATM gene variants c.7271T>G and c.1066–6T>G (IVS10–6T>G) from the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(11):1122–8.

Sawyer SL, Tian L, Kähkönen M, Schwartzentruber J, Kircher M, Majewski J, et al. Biallelic mutations in BRCA1 cause a new Fanconi anemia subtype. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(2):135–42.

Domchek SM, Tang J, Stopfer J, Lilli DR, Hamel N, Tischkowitz M, et al. Biallelic deleterious BRCA1 mutations in a woman with early-onset ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(4):399–405.

Keupp K, Hampp S, Hübbel A, Maringa M, Kostezka S, Rhiem K, et al. Biallelic germline BRCA1 mutations in a patient with early onset breast cancer, mild Fanconi anemia-like phenotype, and no chromosome fragility. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(9): e863.

Rainville I, Hatcher S, Rosenthal E, Larson K, Bernhisel R, Meek S, et al. High risk of breast cancer in women with biallelic pathogenic variants in CHEK2. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(2):503–9.

Adank MA, Jonker MA, Kluijt I, van Mil SE, Oldenburg RA, Mooi WJ, et al. CHEK2*1100delC homozygosity is associated with a high breast cancer risk in women. J Med Genet. 2011;48(12):860–3.

Renaux-Petel M, Charbonnier F, Théry JC, Fermey P, Lienard G, Bou J, et al. Contribution of de novo and mosaic TP53 mutations to Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Med Genet. 2018;55(3):173–80.

Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, McLellan MD, Johnson KJ, Wendl MC, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1472–8.

Coffee B, Cox HC, Bernhisel R, Manley S, Bowles K, Roa BB, et al. A substantial proportion of apparently heterozygous TP53 pathogenic variants detected with a next-generation sequencing hereditary pan-cancer panel are acquired somatically. Hum Mutat. 2020;41(1):203–11.

Yang X, Song H, Leslie G, Engel C, Hahnen E, Auber B, et al. Ovarian and Breast Cancer Risks Associated With Pathogenic Variants in RAD51C and RAD51D. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(12):1242–50.

Yang X, Leslie G, Doroszuk A, Schneider S, Allen J, Decker B, et al. Cancer Risks Associated With Germline PALB2 Pathogenic Variants: An International Study of 524 Families. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(7):674–85.

Moghadasi S, Meeks HD, Vreeswijk MP, Janssen LA, Borg Å, Ehrencrona H, et al. The BRCA1 c. 5096G>A p.Arg1699Gln (R1699Q) intermediate risk variant: breast and ovarian cancer risk estimation and recommendations for clinical management from the ENIGMA consortium. J Med Genet. 2018;55(1):15–20.

Löfgren L, Eloranta S, Krawiec K, Asterkvist A, Lönnqvist C, Sandelin K. Validation of data quality in the Swedish National Register for Breast Cancer. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):495.

Rosenberg P, Kjølhede P, Staf C, Bjurberg M, Borgfeldt C, Dahm-Kähler P, et al. Data quality in the Swedish Quality Register of Gynecologic Cancer - a Swedish Gynecologic Cancer Group (SweGCG) study. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(3):346–53.

Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talbäck M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):27–33.

National clinical cancer care guideline, -epithelial ovarian; version 4.0. Confederation of Regional Cancer Centers in Sweden. 2022. Available from: https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/aggstockscancer-epitelial/vardprogram/.

Acknowledgements

The SWEA consortium wishes to thank all patients and personnel at the oncogenetic clinics participating in this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. Financial support for this study was provided by the Swedish Cancer Society (CAN 2011/323 and CAN 2012/509), the Mrs Berta Kamprad Foundation, the Lund-Lausanne L2-Bridge/Biltema Foundation, the Mats Paulsson Foundation, the Skåne University Hospital and Region Skåne foundations, Region Stockholm (grant number: FoUI-961732 and SLL 500306), the Swedish governmental funding (ALF). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ÅB, HE, BA, ZE, AL, BM, YPK, MSA and AW contributed to the conception and design of the study. AÖ, AR, BA, ZE, AKS, EK, AL, BM, YPK, MSA, ET, AW and HE included patients, provided biological samples and clinical data. AÖ and HE performed registry matching and statistical analysis. AÖ, AR and HE wrote the main manuscript with input from all authors. TT, KH, AK and ÅB performed laboratory and bioinformatics analysis and wrote the laboratory methods description. AK designed the lolliplot figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board in South Sweden (EPN Lund), Dnr 2011/349 and 2011/652. All patients submitted written consent prior to inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

HBOC genetic testing criteria in Sweden 2012-2018. Discordant classification justification. Supplementary methods.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Unique pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants detected in the Swedish cohort. Table S2. Splice site variants not affecting the canonical +- 1,2 basepairs. Table S3. Detailed assessment of TP53 carriers in the Swedish cohort. Table S4a. Diagnostic yield of pathogenic variants per gene in subgroups of women with breast and/or ovarian cancer. Table S4b. Pathogenic variants per gene in breast cancer subgroups. Table S5. Women with two pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants. Table S6. Gene domains and regions depicted in lolliplots. Table S7. Sequences of adapters with 6 nucleotide long barcode sequences. Table S8. Sequences of adapters with 8 nucleotide long barcode sequences. Table S9. SureSelect custom hybrid selection assay design. Table S10. Primers for cDNA sequencing and minigene assays for analyses of splicing.

Additional file 3: Figure S1.

Lollipop plots showing the location and frequency of PVs in BARD1, BRIP1, CDH1, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D and TP53.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Öfverholm, A., Törngren, T., Rosén, A. et al. Extended genetic analysis and tumor characteristics in over 4600 women with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 23, 738 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11229-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11229-y