Abstract

Background

The prognosis of patients with NSCLC harboring oncogenic driver gene alterations, such as EGFR gene mutations or ALK fusion, has improved dramatically with the advent of corresponding molecularly targeted drugs. As patients were followed up for about five years in most clinical trials, the long-term outcomes beyond 5 years are unclear. The objectives of this study are to explore the clinical course beyond five years of chemotherapy initiation and to investigate factors that lead to long-term survival.

Methods

One hundred and seventy-seven patients with advanced, EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged NSCLC who received their first chemotherapy between December 2008 and September 2015 were included. Kaplan Meier curves were drawn for the total cohort and according to subgroups of patients’ characteristics.

Results

Median OS in the total cohort was 40.6 months, the one-year survival rate was 89%, the three-year survival rate was 54%, and the five-year survival rate was 28%. Median OS was 36.9 months in EGFR-mutated patients and 55.4 months in ALK-rearranged patients. The OS curve seemed to plateau after 72 months, and most of the patients who were still alive after more than five years are on treatment. Female sex, age under 75 years, an ECOG PS of 0 to 1, ALK rearrangement, postoperative recurrence, and presence of brain metastasis were significantly associated with longer OS.

Conclusions

A tail plateau was found in the survival curves of patients with advanced, EGFR-mutated and ALK-rearranged NSCLC, but most were on treatment, especially with EGFR-mutated NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, lung cancer cases and deaths are increasing. In 2020, GLOBOCAN estimated 2.2 million new cases (11.4% of total cancer cases) and 1.79 million deaths (18.0% of total cancer deaths), making it the most frequent cancer and cause of death due to cancer [1]. The 5-year overall survival rate for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains poor, from 68% in patients with stageIB disease to 0–10% in patients with stage IVA/IVB disease [2]. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program has reported a five-year relative survival rate for unselected patients with distant-stage NSCLC of just 6.9% [3].

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutations were discovered in 2004 and it was reported that EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) shrink tumors of NSCLC carrying this mutation [4]. Several phase III trials comparing EGFR-TKIs and platinum combination therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC had been reported, and in all of these trials, the EGFR-TKIs groups had significantly better results in term of progression-free survival (PFS) [5,6,7]. In the FLAURA trial, the osimertinib group had significantly better PFS than the standard-treatment group receiving gefitinib or erlotinib [8]. Therefore, the use of osimertinib is recommended as first-line chemotherapy for EGFR-mutated NSCLC as well as other EGFR-TKIs with or without anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) antibodies [9]. In the FLAURA trial, median overall survival (OS) was 38.6 months in the osimertinib group and 31.8 months in the gefitinib or erlotinib group [10], with the advent of EGFR-TKIs improving prognosis in the EGFR-mutated NSCLC.

Analplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is one of the receptor tyrosine kinases. The fusion gene of echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) and the ALK gene was discovered in lung cancer cells in 2007 [11]. Its inhibitor, crizotinib, showed prominent effects in patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC [12, 13]. Later, a second-generation ALK inhibitor was developed, alectinib, which inhibits ALK kinase activity more selectively. Phase III clinical trials comparing crizotinib and alectinib as the first-line chemotherapy, the so-called ALEX and J-ALEX studies, demonstrated that alectinib was superior to crizotinib in term of PFS [14, 15]. Based on these studies, alectinib is recommended as first-line chemotherapy for ALK-rearranged NSCLC. OS in the ALEX trial was 57.4 months in the crizotinib group and unpredictable in the alectinib group, indicating a prominent prolongation of OS.

There are not many reports showing long-term efficacy for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC, and few reports showing long-term efficacy beyond 5 years. Ten of 124 NSCLC patients survived more than five years, and these patients had Performance status (PS) 0–1 and adenocarcinoma, suggesting that good PS is a factor for long-term survival in the study published in 2010 [16]. Twenty of the 137 patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC were five-year survivors in the study published in 2016 [17]. On multivariate analysis, exon 19 deletions, absence of extrathoracic or brain metastasis, and not being a current smoker were associated with prolonged OS. However, these papers included only EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients, and were reported several years ago with shorter follow-up periods. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have shown the benefit of prolonging PFS and OS with a “tail-plateau” on Kaplan Meier survival curves, and have been introduced into daily clinical practice [18]. On the other hand, there have been no reports investigating longer outcomes of more than five years or checking for the existence of a “tail-plateau” in the survival curves of patients with EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged NSCLC.

The primary objective of this study was to explore the survival past five years from the initiation of chemotherapy. Secondary objective was to investigate factors that lead to long-term survival in EGFR-mutated and ALK-rearranged NSCLC, in real-world clinical settings.

Methods

Study design and patients

Patients enrolled in this study had clinical stage III, clinical stage IV, or postoperative recurrence of EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged NSCLC, or radiotherapy with curative intent, and received their first chemotherapy at Juntendo University Hospital between December 10, 2008, and September 30, 2015. The presence of an EGFR mutations was evaluated by the Cycleave method or Scorpion-ARMS method, and ALK rearrangement was evaluated by a highly sensitive immunohistochemical (IHC) method or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). The above criteria were met for 177 patients with EGFR -mutated or ALK-rearranged NSCLC; 155 patients had EGFR-mutated and 22 patients had ALK-rearranged NSCLC.

Data collection

All data were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records. Patient characteristics, treatment, and outcomes were extracted. Patient-specific variables included age, sex, smoking status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG PS), tumor histology, genetic mutation, staging, presence of extrathoracic metastasis, and presence of brain metastasis (Tables 1 and 3). Schedules of treatments and outcomes were also collected. The histological analysis of the tumor was based on the WHO classification. Staging was performed for all patients according to the TNM classification of the Union International for Cancer Control (UICC) ( 7th edition, 2012) [19]. All patients underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax and abdomen, a bone scintigram or positron emission tomography scan, and a brain CT or magnetic resonance imaging for TNM staging before the initiation of first-line chemotherapy, and the presence or absence of extrathoracic and brain metastases was determined. Those patients with a pleural effusion alone were not included among those with extrathoracic metastases. Databases were locked on September 30, 2020. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine (H21-0053).

Statistical considerations

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initiation of first-line chemotherapy to the date of death, and was censored at the date of the last visit for patients whose deaths could not be confirmed. Subgroup analyses of OS were performed. Descriptions of the eight subgroups are listed in Supplemental Fig. 1 and include genetic mutation, age, sex, smoking status, ECOG PS, stage, presence of extrathoracic metastases, and presence of brain metastases. OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank tests were performed to compare survival between two or three groups (Supplemental Figs. 1 and 2). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Hazard ratios were calculated with univariate and multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazard model) (Table 2). All analyses were performed using JMP®11 for Windows (SA, Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

All 177 included patients started their first chemotherapy between December 10, 2008, and September 30, 2015. There were 155 patients with EGFR mutations and 22 with ALK rearrangements. The median follow-up time was 36.9 months (range, 0.5–131.4) in the total cohort. The median follow-up time were 35.5 months (range, 0.5–131.4) with EGFR mutations and 51.8 months (range, 0.8–131.4) with ALK rearrangements. The median follow-up time was 89.2 months (64.6–131.4) in overall surviving patients. The median follow-up time were 89.4 months (range, 70.8–131.4) with EGFR mutations and 82.8 months (range, 64.6–131.4) with ALK rearrangements in survival patients. At the time of database lock, of the EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients, 17 patients (10.9%) were alive, 17 (10.9%) had been lost to follow up, and 121 (78.0%) had died. On the other hand, six patients (27.2%) were alive, three (13.6%) were lost to follow-up, and 13 (59.0%) had died among those patients with ALK rearrangements. Thirty-seven patients (23.8%) with EGFR mutations and nine (40.9%) with ALK rearrangements survived more than five years. In the patients with an EGFR mutation, the median total duration of EGFR-TKI treatments was 18.09 (range, 0–128.61) months; for cytotoxic chemotherapy, it was 8.08 (range, 0–64.37) months; and for immunotherapy, it was 1.34 (range, 0–9.53) months. In the ALK-rearranged patients, the median total duration of ALK-TKI treatment was 31.36 (range, 0–101.87) months; for cytotoxic chemotherapy, it was 8.17 (range, 0–44.18) months; and for immunotherapy, it was 0.69 (range, 0–0.69) months.

The clinical and pathological characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. The median age at the initiation of first-line chemotherapy was 65 years (range, 34–89). Percentages were higher for females (53.6% vs 46.3%) and never-smokers (52.5% vs 44.5%). One hundred and fifty patients (84.7%) had an ECOG PS of 0–1, and twenty-one patients (11.7%) had a value of 2 or more. In terms of histology, 93.2% of patients had adenocarcinoma. Seventy of 177 patients relapsed after surgery. Extrathoracic metastases were found in 113 patients (63.8%) and brain metastases were found in 45 patients (25.4%).

The median number of chemotherapeutic regimens was three (range, 1–14), the median number of molecular targeted drugs was two (range, 0–7), and the median number of cytotoxic chemotherapy was one (range, 0–7).

Survival

In the whole cohort, median survival time (MST) was 40.6 (95% CI, 32.9 to 45.2) months, the one-year survival rate was 89 (95% CI, 84.4 to 93.7) %, the three-year survival rate was 54 (95% CI, 46.7 to 61.7) %, and the five-year survival rate was 28 (95% CI, 22.1 to 35.7) % (Fig. 1). The OS curve seemed to plateau after 72 months, and survival rate at this point was 20.3 (95% CI, 13.6 to 27.0)% in EGFR-mutated patients and 46.0 (95% CI, 24.1 to 67.8) % in ALK-rearranged patients. Median OS was 36.9 (95% CI, 29.6 to 43.5) months in EGFR-mutated patients and 55.4 (95%CI, 32.9 to 111.3) months in ALK-rearranged patients (Supplemental Fig. 1-A). Statistically significant differences in OS were observed in five subgroups with log-rank test. Variables associated with significantly longer OS were: age less than 75 years (p = 0.027) (Supplemental Fig. 1-B), ECOG PS of 0 or 1 (p = 0.0002) (Supplemental Fig. 1-E), postoperative recurrence (p = 0.0015) (Supplemental Fig. 1-F), absence of extrathoracic metastases (p < 0.0001) (Supplemental Fig. 1-G), and absence of brain metastases at baseline (p = 0.0009) (Supplemental Fig. 1-H).

The number of patient with EGFR-mutated patients for the each subtype of EGFR gene was 74 patients (47.7%) with Exon 19 deletion, 63 patients (40.6%) with Exon 21 L858R, four patients (2.6%) with Exon 18 G719A/C/S, and three patients with Exon L861Q (Supplemental Table 1). There was no significant difference in survival between 19 del, L858R and others groups (Supplemental Fig. 2).

The univariate analysis was performed using the Cox’s proportional hazards model. The univariate analysis showed five variables to be associated with overall survival: age (< 75 141/177 vs. ≧75 36/177; p = 0.047); ECOG PS (0–1 135/177 vs. 2–4 21/177; p = 0.0002); Stage (post operative recurrence 70/177 vs. StageIII or IV 107/177; p = 0.0007); brain metastasis (presence 45/177 vs. absence 132/177; p = 0.0009); extrathoracic metastasis (presence 113/177 vs. absence 64/177; p = 0.0002) (Table 2). The multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox’s proportional hazards model. Six variables were consistently associated with significantly longer OS: female sex, age under 75 years, ECOG PS of 0 or 1, ALK-rearranged, postoperative recurrence, and absence of brain metastasis (Table 2).

Subsequent clinical course in patients who survived five years or more

The clinical and pathological characteristics of patients surviving five years or more are shown in Table 3. Of 155 patients with EGFR mutation, 37 patients (23.8%) were alive for longer than five years. On the other hand, of 22 patients with ALK rearrangement, nine (40.9%) were alive for longer than five years.

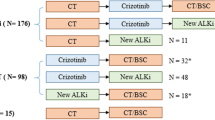

Figure 2 shows a swimmer plot of patients with EGFR mutations who have survived more than five years since their first chemotherapy; 1–37 designates each patient, as thirty-seven patients were alive for more than five years. In five patients, disease had been stable with just one EGFR-TKI, and in two, disease had been stable with two EGFR-TKIs. In the other patients, not only EGFR-TKIs, but also cytotoxic chemotherapy or immunotherapy were used to control their disease. In cases with long-term survival, EGFR-TKIs tended to be used for a longer period than the other agents, and some cases survived for 10 years or more with longer EGFR-TKI use. Figure 3 shows a swimmer’s plot of ALK-rearranged patients who have survived more than five years since their first chemotherapy; 1–9 designates each patient, as nine patients were alive for more than five years. Cases 1, 2, 4, and 9 were treated before the launch of ALK-TKI, and cytotoxic chemotherapy was used as first chemotherapy. As cases 7 and 8 were treated after the launch of alectinib, this was used as their first chemotherapy. In case 3, the disease was stable with a second generation ALK-TKI. In cases 5 and 9, disease was stable even after cessation of ALK-TKI.

Discussion

As described in the introductory section, the discovery of driver oncogenes and the development of their specific inhibitors have improved the survival of patients with advanced NSCLC. ICIs were also found to be effective for the treatment of advanced NSCLC, and as they can suppress cancer progression for a longer time, a “tail-plateau” can be seen in Kaplan–Meier OS curves. There is no evidence that molecular targeted agents have the potential to cure lung cancer or to suppress cancer progression for a long time like ICIs. In the adjuvant setting, there is a phase 3 study, CTONG 1104, that compared gefitinib with vinorelbine plus cisplatin as adjuvant treatment for stage II-IIIA (N1-N2) EGFR-mutated NSCLC [20]. Adjuvant therapy with gefitinib in patients with early-stage NSCLC and EGFR mutation demonstrated improved disease-free survival (DFS) over standard-of-care chemotherapy, but the advantage of DFS did not translate into a significant difference in OS. IMPACT (WJOG6410L) is randomized phase 3 trial that compared gefitinib with vinorelbine plus cisplatin as an adjuvant treatment for stage II to III EGFR-mutated NSCLC after complete resection, but gefitinib cannot significantly prolong DFS and OS [21]. ADAURA is a phase 3 trial that compared osimertinib with placebo for three years in patients with completely resected, stage IB to IIIA, EGFR-mutated NSCLC. DFS was significantly longer among those who received osimertinib than among those who received placebo, but OS data are too immature to allow evaluation of any benefit here [22]. We could find no report on adjuvant ALK-TKI in ALK-rearranged NSCLC.

In this study, we investigated factors related to long-term survival with advanced EGFR-mutated and ALK-rearranged NSCLC. The MST of all patients was 40.6 months. In the subgroup analysis, the MST in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients was 36.9 months and the MST in ALK-rearranged NSCLC patients was 55.4 months, tending to be longer in the latter. The five-year survival rate of EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients was 23.8%, and that of ALK-rearranged NSCLC patients was 40.9%. When multivariate analysis was performed on long-term survival factors, applying Cox’s proportional hazard model, six factors were significant. In descending order of hazard ratio these are: ECOG PS, postoperative recurrence, driver mutation, presence or absence of brain metastasis, sex, and age. And an approximately 2.7-fold difference was observed between the PS: 0–1 group and the PS: 2–4 group.

We also investigated the clinical course of long-term survivors after five years. There are some long-term survivors among patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements, and the survival curve appears to have a tail-plateau as shown in Supplemental Fig. 1-A. However, when the details of clinical courses were investigated as shown in swimmer’s plots, most of the patients had been treated with several types of chemotherapy. In five patients (cases 3, 7, 8, 9, and 13), their disease had been stable on just one EGFR-TKI, and in two patients (cases 1 and 15), their disease had been stable on two EGFR-TKIs (Fig. 2). In some cases, the use of ALK-TKIs was continued for more than five years. In case 3, the disease was stable with a second generation ALK-TKI (Fig. 3). In these cases, the disease may be cured or be in a “nearly cured state” with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. However, because it is difficult to stop tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC, it is impossible to know whether the disease is cured. In two patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC (cases 5 and 9), their disease was stable even after cessation of their ALK-TKI. This suggests an ALK-TKI for ALK-rearranged NSCLC has more potential to suppress the disease for a longer time like immunotherapy in patients at an advanced stage, and is effective for improving OS in an adjuvant setting than EGFR-TKI for EGFR-mutated NSCLC.

In Japan, osimertinib was approved and used as the first chemotherapy for EGFR- mutated inoperable or recurrent NSCLC in 2018. Since the subjects of this study were patients whose first chemotherapy was before osimertinib approval, from December 2008 to August 2015, 69% (108/155 patients) of patients received first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs as their first chemotherapy. In this study, the OS of EGFR-mutated NSCLC was 36.9 months, which was longer than that in the IPASS study, at 21.6 months [23]. The reason may be that 16% (26/155) of patients took osimertinib. In addition, Jessica et al. reported that the OS in patients with EGFR-mutated lung cancer was 30.9 months. The five-year survival rate was 23.8%, which tended to be longer than previously reported [17].

In Japan, crizotinib was approved and used as the first chemotherapy for ALK-rearranged inoperable or recurrent NSCLC in 2012. Later, a phase 3 trial was conducted comparing pemetrexed or docetaxel as second-line chemotherapy and cisplatin or carboplatin plus pemetrexed as first-line chemotherapy with crizotinib, and a significant prolongation of PFS was observed [12, 13]. In addition, alectinib is an ALK inhibitor that selectively exhibits kinase inhibitory activity against ALK, and was approved in Japan in 2014. In this study, ALK-TKIs were used in cases subsequent to first chemotherapy, following the launch of ALK-TKIs.

When multivariate analysis was performed on long-term survival factors, applying Cox’s proportional hazard model, six factors (ECOG PS, postoperative recurrence, driver mutation, sex, age and presence or absence of brain metastases) were significant. Park et al. and Lee et al. examined clinical features associated with survival in patients with EGFR- mutated advanced NSCLC treated with an EGFR-TKI and identified tumor burden, quantified by the number of metastatic sites, as one such feature [17, 24, 25]. Brain metastasis is considered to be a prognostic factor in lung cancer. Incomplete penetration of the drug into the CNS through the blood–brain barrier worsens the response to first-generation TKI treatment of the brain and meninges [26].

This research, however, is subject to several limitations. The first is that owing to the retrospective design, undefined biases may have been present and influenced the clinical outcome. The next is that the data collection and analysis were performed at a single center, and the patient sample size is small. Finally, the patients chosen for this study were those in whom initial treatment was started more than five years ago, and the standard treatment at the time was different from current therapy.

Conclusions

There are long-term survivors among patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements, and the survival curve appears to have a tail-plateau. However, most patients were treated with several types of chemotherapy, and were on treatment at the last follow up. In two NSCLC patients with ALK rearrangement, their disease was stable even after cessation of ALK-TKI, suggesting that ALK-TKI for ALK-rearranged NSCLC has more potential to suppress the disease for a longer time like immunotherapy in patients with advanced stage disease, and is effective at improving OS in the adjuvant setting than EGFR-TKI for EGFR-mutated NSCLC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- EGFR :

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ALK :

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Duma N, Santana-Davila R, Molina JR. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(8):1623–40.

Howlader N NA, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017. based on November 2019 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2020.

Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497–500.

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–57.

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380–8.

Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–8.

Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–25.

Ettinger, DS WD, Aggarwal C, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman JR, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 3.2022; Available at: https://www.nccn.org/. Accessed 21 Mar 2022.

Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41–50.

Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–6.

Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn MJ, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385–94.

Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2167–77.

Hida T, Nokihara H, Kondo M, Kim YH, Azuma K, Seto T, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (J-ALEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):29–39.

Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):829–38.

Kaira K, Takahashi T, Murakami H, Tsuya A, Nakamura Y, Naito T, et al. Long-term survivors of more than 5 years in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;67(1):120–3.

Lin JJ, Cardarella S, Lydon CA, Dahlberg SE, Jackman DM, Jänne PA, et al. Five-year survival in EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(4):556–65.

Antonia SJ, Borghaei H, Ramalingam SS, Horn L, De Castro Carpeño J, Pluzanski A, et al. Four-year survival with nivolumab in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):1395–408.

Marshall HM, Leong SC, Bowman RV, Yang IA, Fong KM. The science behind the 7th edition tumour, node, metastasis staging system for lung cancer. Respirology. 2012;17(2):247–60.

Zhong WZ, Wang Q, Mao WM, Xu ST, Wu L, Wei YC, et al. Gefitinib versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin as adjuvant treatment for stage II-IIIA (N1–N2) EGFR-Mutant NSCLC: final overall survival analysis of CTONG1104 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):713–22.

Tada H, Mitsudomi T, Misumi T, Sugio K, Tsuboi M, Okamoto I, et al. Randomized phase III study of gefitinib versus cisplatin plus vinorelbine for patients with resected stage II-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer with. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(3):231–41.

Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, John T, Grohe C, Majem M, et al. Osimertinib in resected. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1711–23.

Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Sunpaweravong P, Leong SS, Sriuranpong V, et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(21):2866–74.

Park JH, Kim TM, Keam B, Jeon YK, Lee SH, Kim DW, et al. Tumor burden is predictive of survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and with activating epidermal growth factor receptor mutations who receive gefitinib. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(4):383–9.

Lee JY, Lim SH, Kim M, Kim S, Jung HA, Chang WJ, et al. Is there any predictor for clinical outcome in EGFR mutant NSCLC patients treated with EGFR TKIs? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(5):1063–70.

Heon S, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, Joshi VA, Butaney M, Britt GJ, et al. The impact of initial gefitinib or erlotinib versus chemotherapy on central nervous system progression in advanced non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(16):4406–14.

Acknowledgements

No further acknowledgements beyond declarations are listed above.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S SS, TS, TA, DH, KK, SX, and KM carried out the studies, S SS, RS, and NS participated in collecting data. S SS, TS, and TA performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. S SS, TS, and TA drafted the manuscript, and S SS wrote the manuscript. YM, KeT, FT, KaT revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the 2nd hospital Ethics Review Committee in 2021 (18/5/2021) at Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan (reference number: 21–053). Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. According to the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research in Japan and the Institutional Review Board of Juntendo University, the need for consent is deemed unnecessary. Instead, the opt-out method, which provides potential candidates with opportunities to decline to participate through information disclosure via posting on the website of Juntendo University, was applied.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplemental Table 1. Distribution of EGFR mutation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimamura, S.S., Shukuya, T., Asao, T. et al. Survival past five years with advanced, EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer—is there a “tail plateau” in the survival curve of these patients?. BMC Cancer 22, 323 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09421-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09421-7