Abstract

Background

The impact of microsatellite status on lymph node (LN) yield during lymphadenectomy and pathological examination has never been assessed in gastric cancer (GC). In this study, we aimed to appraise the association between microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) and LN yield after curative gastrectomy.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 1757 patients with GC undergoing curative gastrectomy and divided them into two groups: MSI-H (n = 185(10.5%)) and microsatellite stability (MSS) (n = 1572(89.5%)), using a five-Bethesda-marker (NR-24, BAT-25, BAT-26, CAT-25, MONO-27) panel. The median LN count and the percentage of specimens with a minimum of 16 LNs (adequate LN ratio) were compared between the two groups. The log odds (LODDS) of positive LN count (PLNC) to negative LN count (NLNC) and the target LN examined threshold (TLNT(x%)) were calculated in both groups.

Results

Statistically significant differences were found in the median LN count between MSI-H and MSS groups for the complete cohort (30 vs. 28, p = 0.031), for patients undergoing distal gastrectomy (DG) (30 vs. 27, p = 0.002), for stage II patients undergoing DG (34 vs. 28, p = 0.005), and for LN-negative patients undergoing DG (28 vs. 24, p = 0.002). MSI-H was an independent factor for higher total LN count in patients undergoing DG (p = 0.011), but it was not statistically correlated to the adequate LN ratio. Statistically significant differences in PLNC, NLNC and LODDS were found between MSI-H GC and MSS GC (all p < 0.001). The TLNT(90%) for MSI-H and MSS groups were 31 and 25, respectively. TLNT(X%) of MSI-H GC was always higher than that of MSS GC regardless of the given value of X%.

Conclusions

MSI-H was associated with higher LN yield in patients undergoing gastrectomy for GC. Although MSI-H did not affect the adequacy of LN harvest, we speculate that a greater lymph node yield is required during pathological examination in MSI-H GC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. While systemic and multimodal treatment have been widely applied in GC, radical surgical resection remains the cornerstone of curative treatment [2]. Adequate lymph node (LN) yield, an essential quality measure for radical resection, requires a minimum of 16 LNs for precise staging [2,3,4].

Several publications have found that the munber of LN yield in colorectal cancer (CRC) depended not only on the extent of lymphadenectomy performed by surgeons but also on some tumoral characteristics, especially the microsatellite status [5,6,7,8]. In GC, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors have also been identified as one of the main subtypes [9]. Although many clinical and pathological characteristics of MSI-H phenotype in GC seem similar to those in CRC, we were unable to find any studies that mentioned the impact of MSI-H phenotype on LN yield. In this study, we aimed to examine whether there was any correlation between MSI-H and adequate LN yield after gastrectomy.

Methods

Patients

We conducted retrospective analysis on the records of 1948 patients who underwent gastrectomy for GC at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China, between 2017 and 2019. All data were collected from our prospective database and the study was approved by Ruijin hospital ethics committee. We included patients with adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma, excluding those with synchronous double cancers or metastatic GC, those treated with non-curative (R2) resection, and those with unstructured pathological evaluation reports.

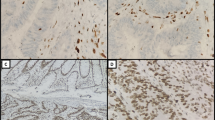

Microsatellite status

Four mismatch repair (MMR) proteins, MLH1, MSH2, PMS2, and MSH6, were tested by immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. Tumors with defective MMR protein expression were considered as MMR deficiency (dMMR). A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method with a five-Bethesda-marker (NR-24, BAT-25, BAT-26, CAT-25, MONO-27) panel was used for dMMR specimens. Tumors with instability at two or more of the five markers were classified as MSI-H whereas other tumors were classified as microsatellite stability (MSS) in our study [10]. The microsatellite status of positive LNs was not tested.

LN retrieval and evaluation

After fixation of the en-bloc specimen in 10% formalin for 48 h, gross dissection of LNs was performed by palpation and thin slice inspection. The specimen was routinely re-examined when fewer than 16 LNs were dissected after primary gross examination. Pathological results were reported in line with the AJCC Cancer Staging Guidelines 8th edition [4]. The pathologists involved were unaware of the future inclusion of specimens in this study at the time of assessment.

We defined the adequate LN ratio as the percentage of specimens with a minimum of 16 LNs during pathological examination. We defined the log odds of positive LNs to negative LNs (LODDS) as: LODDS = log [(PLNC+ 0.1)/(NLNC+ 0.1)], in which PLNC/NLNC means positive/negative lymph node count, respectively. We defined a target LN examined threshold (TLNT(x%)) as the minimum number of LNs yielded to detect a given percentage (X%) of cases with positive LN (LN+). We can calculate the TLNT(x%) from the distribution of LODDS, using this formula: LODDS(1-X%) = log [(1 + 0.1)/(TLNT(X%)-1 + 0.1)]. → TLNT(X%) = 1.1/eLODDS(1-X%) + 0.9 .

Statistical analysis

EpiData 3.1 (a free software available at www.epidata.dk) was utilized for data collection. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 13.0, Chicago, IL, USA) was introduced for statistical analysis. Categorical data was examined by Pearson’s Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact test. Non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was adopted to analyze numerical variables. Linear regression as well as binary logistic regression were performed for multivariate analysis. The difference was statistically significant if two-sided p values < 0.05.

Results

Patient demographics and pathological evaluation

Based on our selection criteria, data for 1757 of 1948 patients (90.2%) were available: 1191 (67.8%) men and 566 (32.2%) females; median age: 62 (range, 22–90) years; 1121 (63.8%) distal, 609 total (34.7%) and 27 proximal (1.5%) gastrectomies. Neoadjuvant therapy was administered to 249 (14.2%) patients.

Microsatellite status was available for all 1757 specimens; MSI-H was found in 185 (10.5%) patients. MSI-H GC was found more frequently among female and elderly patients and more often in tumors located in the gastric antrum and pylorus (p < 0.001 for all). No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups with regard to the proportion of patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy (p = 0.166). Statistically significant differences were found in several pathological characteristics of MSI-H, such as larger tumor size (p < 0.001), more well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (p < 0.001), lymphovascular emboli (p = 0.002), N0 stage (p < 0.001), NLNC (p < 0.001), and M0 stage (p = 0.002), and fewer perineural invasion (p < 0.001), tumor deposit (p = 0.009), and PLNC(p < 0.001) (Table 1).

LN count and adequate LN ratio

In the complete cohort of 1757 GC, a median of 28 LNs was retrieved, and the overall adequate LN ratio was 92.3% (1621/1757). Statistically significant differences were found in the median LN count (30 vs. 28, p = 0.031), but not in the adequate LN ratio (95.1% vs. 91.9%, p = 0.145) according to MSI-H and MSS, respectively. When restricted to distal gastrectomy (DG), a statistically significant difference was seen in the median LN count (30 vs. 27, p = 0.002), but not in the adequate LN ratio (95.6% vs. 91.2%, p = 0.061). When DGs were stratified according to AJCC stage, a statistically significant association between microsatellite status and median LN count was found only for AJCC stage II cancers (34 vs. 28, p = 0.005). Median LN counts did not differ statistically significantly between the two groups according to T category. A statistically significant difference in median LN count was found in patients undergoing DG for N0 cancers (28 vs. 24, p = 0.002). Conversely, no statistically significant difference was found in either the median LN count or the adequate LN ratio regardless of the AJCC Stage, T category and N category for patients undergoing total gastrectomy (TG) (Table 2). Further univariate and multivariate analysis demonstrated that MSI-H was an independent factor for total LN count in patients undergoing DG (B = 2.468, 95% CI 0.563 to 4.374, p = 0.011) (Table 3), and so it was in patients undergoing DG who were AJCC stage II (B = 5.105, 95% CI 1.432 to 8.779, p = 0.007) or N0 (B = 2.836, 95% CI 0.160 to 5.513, p = 0.038). MSI-H was not statistically correlated to the adequate LN ratio according to our univariate and multivariate analysis.

LODDS and TLNT(x%)

A statistically significant difference in LODDS was found between MSI-H GC and MSS GC (Mean: − 5.017 vs. -2.727, p < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). As shown in Table 4, to achieve TLNT(90%) during pathological examination, 31 LNs are required to be tested for MSI-H GC, instead of 25 LNs for MSS GC. We found that TLNT(X%) of MSI-H GC was always higher than that of MSS GC regardless of the given value of X%. If we set TLNT at 16 based on the current guideline for lymphadenectomy [4], LODDS would be − 2.619, implicating that 25.6% of LN+ MSI-H cases and 19.1% of LN+ MSS cases would be missed during pathological evaluation.

Discussion

In this study, we found a statistically significant association between MSI-H and a higher LN count after curative gastrectomy, especially in patients undergoing DG and in patients undergoing DG who were AJCC stage II and N0. The absence of any statistically significant difference in LN count for patients undergoing TG could be partially explained by the low prevalence of MSI-H (24/609 = 3.9%) in this subgroup. On the other hand, the microsatellite status has no correlation with the adequate LN ratio irrespective of the extent of resection. However, TLNT(X%) of MSI-H GC was always higher than that of MSS GC regardless of the given value of X%. We speculate that a greater lymph node yield is required during pathological examination in MSI-H GC in order to capture adequate LN+ cases.

High LN harvest after curative gastrectomy for GC has been found to be associated with better 5-year survival [11, 12]. Conversely, insufficient LN retrieval might lead to inaccurate staging [4, 13]. Several factors have been reported to impact LN yield during gastrectomy, such as age [14,15,16], ethnicity [14, 16], body mass index [17], tumor stage at diagnosis [14, 16, 18], institution volume [14, 15], and obviously, the extent of resection (TG vs. DG) [3, 19]. Of note, however, none of the above-mentioned publications analyzed genomic characteristics of GC. GCs can be classified into different molecular subtypes although the number of subtypes remains controversial and unclarified [9, 20]. GC with MSI-H phenotype is, without any doubt, one of the main subtypes due to its distinct histopathological patterns and particular clinical features [9, 21].

MSI-H prevalence in our study (10.5%) is in accordance with the literature for Asians (8.3%) [22], and close to the 9% overall rate reported in the meta-analysis by Polom et al. [23], but lower than those in worldwide genomic analysis studies (23 and 22%, respectively) [9, 24]. Indeed, MSI-H prevalence in Western patients varies from 8 to 45% [25, 26]. Several publications have underscored this difference between Asiatic patients and Western patients [21]. Apart from ethnicity, the lack of a standardized and quality-controlled diagnostic algorithm of MSI-H might be responsible for this variation in prevalence [25].

Several of the well-known associations between clinical/pathological features of GC and MSI-H were confirmed in our study, including elder age [22, 27,28,29], female gender [22, 27,28,29], occurrence in the distal stomach [22, 27, 28], larger tumor size [22], more mucinous pathology type [22], more lymphovascular emboli [22], limited LN involvement [22, 23, 25, 30], less advanced AJCC stage [25, 30], and in particular, a higher total LN count in MSI-H patients undergoing DG for AJCC stage II tumors [29].

However, conversely, Kim et al. [22] found a larger proportion of T2–4 tumors and more perineural invasion in MSI-H GC. Oki et al. [31] postulated that LN involvement was positively correlated to MSI-H GC. We speculate that the small sample size (414 and 240 cases, respectively) of these two studies and the high molecular heterogeneity of GC could partially explain these differences.

Our findings have several points in common with CRC studies: increased LN yield was strongly related to tumor location, tumor stage and microsatellite status [6, 7]. According to a location-specific analysis, no statistically significant difference in adequate LN was found between MSI-H and MSS tumors in the proximal colon [8]. In a further subclassification by UICC stage, a statistically significant association between MSI-H and higher LN count as well as higher adequate LN ratio could only be observed in stage I-II CRC (N0 tumors) but not in stage III CRC (N+ tumors) [8]. Moreover, lymphatic spread was less likely in MSI-H than MSS tumors [32]. Buckowitz et al. [33] found that microsatellite status was an independent predictor of distant metastases and attributed this finding to local lymphocyte infiltration in MSI-H CRCs.

The reasons for which MSI-H is associated with a higher total LN count in LN-negative stages in GC or CRC are difficult to ascertain for the moment. One reasonable explanation might be in the underlying molecular biological mechanism of MSI: the higher mutational rate in MSI-H tumors could potentially encode non-self immunogenic neoepitopes, which are known to induce an intense immune reaction and recruitment of lymphocytes [21]. This remarkably strong lymphocytic infiltration is described as “Crohn’s like” lymphoid reaction in CRC with MSI, a specific feature of this cancer type [8, 33]. As the size of LNs in MSI-H cancers was larger than that in MSS cancers [34], this could facilitate LN detection during the gross examination. However, in LN+ stages, this influence of tumor immunogenicity is overshadowed by a greater inflammatory response caused by tumor-induced tissue destruction and environmental invasion [8]. As neoadjuvant therapy may attenuate this MSI-related immune reaction, this might explain why no statistically significant difference was found between the MSI-H and MSS groups in the LN count in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy.

Emerging data seem to indicate that MSI-H status has a favorable prognosis [21, 29, 30]. Polom et al. speculated that MSI-H tumors showed a high rate of N0 stage, a lower number of lymph node metastases, and a less extensive spread to lymph node stations than MSS tumors [35]. Since MSI-H GC has higher NLNC and lower PLNC, it is easy to know that more LNs need to be yielded by pathologist to avoid missing LN+ MSI-H GC, leading to a higher TLNT(X%) compared to MSS GC. TLNT(X%) was used to investigate the adequacy of pathological yield of LNs in previous studies [36, 37]. If the TLNT for MSI-H and MSS tumors were set at the same level, we can imagine that a larger proportion of LN+ cases would be missed in MSI-H GC compared to MSS GC. Thus, we speculate that a greater lymph node yield is required during pathological examination in MSI-H GC but this needs to be verified by further investigation.

Among the strengths of our study, this was, to the best of our knowledge, the first assessment of the potential association between MSI-H and LN yield in GC. Secondly, the study was conducted in a Chinese population, where the incidence of GC is relatively high. Thirdly, the sample size was large (1757 patients), increasing the feasibility of stratified and multivariate analysis to reduce the effect of confounding factors, such as the extent of resection.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this was a retrospective observational single-center study, only including Chinese patients. Secondly, MSI-H was detected by PCR method only when dMMR status was confirmed by IHC method. However, previous studies have shown a good correlation between the IHC and PCR method [10, 38]. Thirdly, microsatellite status of positive LNs was not tested, ignoring the probable heterogeneity between primary tumor and metastatic LNs [25, 39]. Lastly, LN counts depend on the type of surgical operation performed, the extended character of LN dissection of each individual surgeon, as well as the diligence with which pathologists search for LNs [3, 40].

Conclusions

MSI-H was associated with higher LN yield in patients undergoing curative gastrectomy, especially for LN-negative GC. Although MSI-H did not affect the adequacy of LN harvest, a greater LN yield during pathological examination is suggested to capture adequate LN+ cases in MSI-H GC. Further investigations concerning the prognostic value of LN count in GC patients should be conducted once long-term survival information of these patients has been obtained.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- LN:

-

Lymph node

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- MSI-H:

-

Microsatellite instability-high

- MMR:

-

Mismatch repair

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemical

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- MSS:

-

Microsatellite stability

- LODDS:

-

Log odds of positive lymph nodes to negative lymph nodes

- PLNC:

-

Positive lymph node count

- NLNC:

-

Negative lymph node count

- TLNT:

-

Target lymph node examined threshold

- DG:

-

Distal gastrectomy

- TG:

-

Total gastrectomy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Das P, Denlinger CS, Fanta P, Farjah F, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Gibson M, Glasgow RE, Hayman JA, Hochwald S, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jaroszewski D, Johung KL, Keswani RN, Kleinberg LR, Korn WM, Leong S, Linn C, Lockhart AC, Ly QP, Mulcahy MF, Orringer MB, Perry KA, Poultsides GA, Scott WJ, Strong VE, Washington MK, Weksler B, Willett CG, Wright CD, Zelman D, McMillian N, Sundar H. Gastric Cancer, version 3.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14(10):1286–312. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2016.0137.

Lu J, Wang W, Zheng CH, Fang C, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Huang CM, Zhou ZW. Influence of Total lymph node count on staging and survival after Gastrectomy for gastric Cancer: An analysis from a two-institution database in China. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(2):486–93. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5494-7.

Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edition: springer. New York; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40618-3.

Morikawa T, Tanaka N, Kuchiba A, Nosho K, Yamauchi M, Hornick JL, Swanson RS, Chan AT, Meyerhardt JA, Huttenhower C, Schrag D, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Predictors of lymph node count in colorectal cancer resections: data from US nationwide prospective cohort studies. Arch Surg. 2012;147(8):715–23. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2012.353.

Berg M, Guriby M, Nordgård O, Nedrebø BS, Ahlquist TC, Smaaland R, Oltedal S, Søreide JA, Kørner H, Lothe RA, Søreide K. Influence of microsatellite instability and KRAS and BRAF mutations on lymph node harvest in stage I-III colon cancers. Mol Med. 2013;19(1):286–93. https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2013.00049.

Belt EJ, te Velde EA, Krijgsman O, et al. High lymph node yield is related to microsatellite instability in colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(4):1222–30. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-2091-7.

Arnold A, Kloor M, Jansen L, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H, von Winterfeld M, Hoffmeister M, Bläker H. The association between microsatellite instability and lymph node count in colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2017;471(1):57–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2150-y.

Cristescu R, Lee J, Nebozhyn M, Kim KM, Ting JC, Wong SS, Liu J, Yue YG, Wang J, Yu K, Ye XS, Do IG, Liu S, Gong L, Fu J, Jin JG, Choi MG, Sohn TS, Lee JH, Bae JM, Kim ST, Park SH, Sohn I, Jung SH, Tan P, Chen R, Hardwick J, Kang WK, Ayers M, Hongyue D, Reinhard C, Loboda A, Kim S, Aggarwal A. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 2015;21(5):449–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3850.

Zhang L, Peng Y, Peng G. Mismatch repair-based stratification for immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8(10):1977–88.

Macalindong SS, Kim KH, Nam BH, Ryu KW, Kubo N, Kim JY, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Kook MC, Choi IJ, Kim YW. Effect of total number of harvested lymph nodes on survival outcomes after curative resection for gastric adenocarcinoma: findings from an eastern high-volume gastric cancer center. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3872-6.

Brenkman HJF, Goense L, Brosens LA, Haj Mohammad N, Vleggaar FP, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. A high lymph node yield is associated with prolonged survival in elderly patients undergoing curative Gastrectomy for Cancer: a Dutch population-based cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(8):2213–23. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5815-5.

Biondi A, D'Ugo D, Cananzi FC, et al. Does a minimum number of 16 retrieved nodes affect survival in curatively resected gastric cancer? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(6):779–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2015.03.227.

Morgan JW, Ji L, Friedman G, Senthil M, Dyke C, Lum SS. The role of the cancer center when using lymph node count as a quality measure for gastric cancer surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):37–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.678.

Baxter NN, Tuttle TM. Inadequacy of lymph node staging in gastric cancer patients: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(12):981–7. https://doi.org/10.1245/ASO.2005.03.008.

Le A, Berger D, Lau M, El-Serag HB. Secular trends in the use, quality, and outcomes of gastrectomy for noncardia gastric cancer in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(9):2519–27. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9386-8.

Wong J, Rahman S, Saeed N, Lin HY, Almhanna K, Shridhar R, Hoffe S, Meredith KL. Effect of body mass index in patients undergoing resection for gastric cancer: a single center US experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(3):505–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2455-y.

Wu ZM, Teng RY, Shen JG, Xie SD, Xu CY, Wang LB. Reduced lymph node harvest after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(6):2086–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/147323001103900604.

Shen Z, Ye Y, Xie Q, Liang B, Jiang K, Wang S. Effect of the number of lymph nodes harvested on the long-term survival of gastric cancer patients according to tumor stage and location: a 12-year study of 1,637 cases. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):431–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.01.029.

Sohn BH, Hwang JE, Jang HJ, et al. Clinical Significance of Four Molecular Subtypes of Gastric Cancer Identified by The Cancer Genome Atlas Project. Clin Cancer Res. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.

Ratti M, Lampis A, Hahne JC, Passalacqua R, Valeri N. Microsatellite instability in gastric cancer: molecular bases, clinical perspectives, and new treatment approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(22):4151–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-018-2906-9.

Kim JY, Shin NR, Kim A, Lee HJ, Park WY, Kim JY, Lee CH, Huh GY, Park DY. Microsatellite instability status in gastric cancer: a reappraisal of its clinical significance and relationship with mucin phenotypes. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.1.28.

Polom K, Marano L, Marrelli D, de Luca R, Roviello G, Savelli V, Tan P, Roviello F. Meta-analysis of microsatellite instability in relation to clinicopathological characteristics and overall survival in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(3):159–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10663.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13480.

Mathiak M, Warneke VS, Behrens HM, Haag J, Böger C, Krüger S, Röcken C. Clinicopathologic characteristics of microsatellite instable gastric carcinomas revisited: urgent need for standardization. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25(1):12–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAI.0000000000000264.

Wirtz HC, Müller W, Noguchi T, Scheven M, Rüschoff J, Hommel G, Gabbert HE. Prognostic value and clinicopathological profile of microsatellite instability in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(7):1749–54.

Marrelli D, Polom K, Pascale V, Vindigni C, Piagnerelli R, de Franco L, Ferrara F, Roviello G, Garosi L, Petrioli R, Roviello F. Strong prognostic value of microsatellite instability in intestinal type non-cardia gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(3):943–50. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4931-3.

An JY, Kim H, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Kim H, Noh SH. Microsatellite instability in sporadic gastric cancer: its prognostic role and guidance for 5-FU based chemotherapy after R0 resection. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(2):505–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.26399.

Beghelli S, de Manzoni G, Barbi S, Tomezzoli A, Roviello F, di Gregorio C, Vindigni C, Bortesi L, Parisi A, Saragoni L, Scarpa A, Moore PS. Microsatellite instability in gastric cancer is associated with better prognosis in only stage II cancers. Surgery. 2006;139(3):347–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.021.

Velho S, Fernandes MS, Leite M, Figueiredo C, Seruca R. Causes and consequences of microsatellite instability in gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(44):16433–42. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16433.

Oki E, Kakeji Y, Zhao Y, Yoshida R, Ando K, Masuda T, Ohgaki K, Morita M, Maehara Y. Chemosensitivity and survival in gastric cancer patients with microsatellite instability. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(9):2510–5. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0580-8.

Buecher B, Cacheux W, Rouleau E, Dieumegard B, Mitry E, Lièvre A. Role of microsatellite instability in the management of colorectal cancers. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(6):441–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2012.10.006.

Buckowitz A, Knaebel HP, Benner A, Bläker H, Gebert J, Kienle P, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Kloor M. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer is associated with local lymphocyte infiltration and low frequency of distant metastases. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(9):1746–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602534.

Rössler O, Betge J, Harbaum L, Mrak K, Tschmelitsch J, Langner C. Tumor size, tumor location, and antitumor inflammatory response are associated with lymph node size in colorectal cancer patients. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(6):897–904. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.227.

Polom K, Marrelli D, Pascale V, Ferrara F, Voglino C, Marini M, Roviello F. The pattern of lymph node metastases in microsatellite unstable gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(12):2341–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2017.09.007.

Arrington AK, Price ET, Golisch K, Riall TS. Pancreatic Cancer lymph node resection revisited: a novel calculation of number of lymph nodes required. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(4):662–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.031.

Arrington AK, O'Grady C, Schaefer K, et al. Significance of lymph node resection after neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic, gastric, and rectal cancers. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004181 Online ahead of print.

Murphy KM, Zhang S, Geiger T, Hafez MJ, Bacher J, Berg KD, Eshleman JR. Comparison of the microsatellite instability analysis system and the Bethesda panel for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancers. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8(3):305–11. https://doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050092.

Choi J, Nam SK, Park DJ, Kim HW, Kim HH, Kim WH, Lee HS. Correlation between microsatellite instability-high phenotype and occult lymph node metastasis in gastric carcinoma. APMIS. 2015;123(3):215–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12345.

Jiang L, Yao Z, Zhang Y, Hu J, Zhao D, Zhai H, Wang X, Zhang Z, Wang D, Gastrointestinal Surgery Ward I, Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Yantai 264000, China. Comparison of lymph node number and prognosis in gastric cancer patients with perigastric lymph nodes retrieved by surgeons and pathologists. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28(5):511–8. https://doi.org/10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2016.05.06.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty [grant number shslczdzk00102 to M.Z], Shanghai Municipal Health Commission [grant number 2019SY030 to L.Z], Shanghai Science and Technology Committee [grant number 18411953200 to J.S] and National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 51803120 to H.S].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C, S. L, C.Y and L. Zang contributed to conceptualization; A. F, J. S and L. Zhang contributed to methodology; Z. C, H.S and J. M contributed to formal analysis and investigation; J. M, S. L and C. Y contributed to data curation; M. Z, J. S, H. S and L. Zang contributed to funding acquisition; Z. C, H.S and L. Zhang contributed to writing of original draft; M. Z, A. F and L. Zang contributed to review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Zhenghao Cai and Haiqin Song should be considered joint first authors. Minhua Zheng and Lu Zang should be considered joint corresponding authors. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964. All experimental protocols were approved by Ruijin Hospital Ethics Committee. The need for informed consent was waived by Ruijin Hospital Ethics Committee because of the retrospective design of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Z., Song, H., Fingerhut, A. et al. A greater lymph node yield is required during pathological examination in microsatellite instability-high gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 21, 319 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08044-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08044-8