Abstract

Background

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-sensitizing mutation, exon 19 deletion consists of several molecular variants. Influences of these variants on clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors remain elusive.

Methods

West Japan Oncology Group 8114LTR is a prospective, multi-institutional biomarker study. Treatment naïve, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients with EGFR-sensitizing mutation received afatinib monotherapy. We conducted a preplanned subset analysis of patients harboring exon 19 deletion. Tumor tissue exon 19 deletion molecular variants were identified by blocking-oligo-dependent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and by Luminex Technology. Plasma cfDNA was also obtained before and after the treatment and EGFR mutations were detected with multiplexed, pico-droplet digital PCR assay.

Results

Among 57 registered patients, twenty-nine patients were exon 19 deletion. Tissue DNA and cfDNA were available in 26 patients. Among the detected seven molecular variants, the most frequent was p.E746_A750delELREA (65.4%). According to the various classifications of molecular variants, twenty one (80.8%) were classified into 15-nucleotide deletion, one (3.8%) into 18-nucleotide deletion, and four patients (15.4%) into other insertion/substitution variant subgroups. The patient subgroup with 15-nucleotide deletion showed significantly longer progression-free survival than patients in other mixed insertion/substitution variant subgroup (p = 0.0244).

Conclusions

The clinical significance of molecular variants of exon 19 deletion on the first line afatinib monotherapy is reported here for the first time. Further investigation is needed for development of better therapeutic strategies.

Trial registration

This trial was registered at UMIN Clinical Trials Registry at 2014/12/4 (UMIN000015847).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been standard provision for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Afatinib, a second generation EGFR-TKI, is an irreversible inhibitor that targets the EGFR and other members of the ERBB tyrosine kinase receptor family. It allows longer progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with NSCLC harboring EGFR-sensitizing mutations compared with platinum based chemotherapy [1, 2]. It has been widely approved in many countries as the first line treatment for NSCLC tumors with EGFR-sensitizing mutations. Deletion mutations of exon 19 and the single point mutation exon 21 Leu858Arg (L858R) are the most common mutations of EGFR, their incidences in Japanese population are 48.2 and 42.7%, respectively [3]. While EGFR-TKIs have high binding affinity for these common mutations, they showed different sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs. Although first and second generation EGFR-TKIs have shown better survival outcomes in patients with exon 19 deletion than in patients with L858R in some studies, it remains inconclusive [1, 3,4,5,6,7,8]. Furthermore, exon 19 deletion mutation has several molecular variants including in-frame deletions, substitutions, and insertions [9, 10]. These variants are heterogeneous, and many deletions almost bind the amino acid residues leucine-747 (L747) to glutamic acid-749 (E749) (LRE) which is located at the N-terminus of the EGFR kinase domain C-helix. This is a key structure for function and activation of EGFR [11,12,13]. Minor variants that do not include these codons are also reported [9]. These molecular mutational variants of exon 19 deletion are associated with different clinical outcomes and might have predictive roles for TKIs [10, 13,14,15,16,17].

We conducted a prospective, multi-institutional phase II biomarker study of EGFR mutated, advanced NSCLC patients treated with afatinib (West Japan Oncology Group [WJOG] 8114LTR). Clinical outcomes were overall response rate 78.6% and median PFS 14.2 months [18, 19]. Additionally, presence of mutated EGFR in plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and its alteration during treatment was suggested to be a good prognostic marker of afatinib [18, 19]. In this preplanned subset study, we identified the molecular variants of EGFR exon 19 deletion in the subset harboring exon 19 deletion of WJOG8114LTR and analyzed their correlations with clinical outcomes of treatment with afatinib.

Methods

Study design and patient population

We recruited pathologically confirmed and previously untreated recurrence or advanced (Stage IIIB/IV) NSCLC patients with EGFR-sensitizing mutations confirmed by approved commercial tests. They received afatinib monotherapy (40 mg q.d.) until progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity. Assessment of tumor response was based on response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST), version 1.1 [20]. The primary endpoint was concordance rate of EGFR mutation status between tumor tissue and plasma. Secondary endpoints included biomarker analyses, detection of mutated EGFR cfDNA using digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method, and identification of exon 19 deletion molecular variants in tumor tissue. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of all participating centers and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was registered at Clinical Trials Registry UMIN (ID: 000015847).

DNA extraction from tissue and blood samples

Genome DNA extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens of surgically resected tissue was performed in an independent clinical laboratory (SRL, Tokyo, Japan). Genomic DNA mass was measured using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000C; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE) as per the manufacturer’s recommendation.

Peripheral whole blood collected in EDTA tubes (BD Vacutainer Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was centrifuged at 1500×g for 10 min at 4 °C and the plasma supernatant was transferred to 50 mL conical tubes (BD Falcon, Corning, NY) and stored at − 80 °C until use. Plasma DNA was isolated using the QIAmp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was eluted in AVE buffer (50 μL). Approximately 40 μL of plasma DNA was concentrated to about 10 μL by SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). DNA concentration was measured by Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Variant analysis of EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation

These molecular variants were the first twenty of the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer (COSMIC) frequencies as listed in Additional file 1: Table S1 [21]. Deletion in exon 19 was analyzed by the blocking-oligo-dependent (bo) PCR and Luminex technology using the tumor tissues before afatinib treatment. By blocking non-target amplification, only target sequences are amplified using universal PCR primers [22, 23]. When template DNA is wild type, blocking oligo binds to the complementary locus, and primer extension is inhibited. When template DNA is mutated, blocking oligo cannot bind to the target so primer extension is prolonged. The blocker can be a modified DNA oligonucleotide that does not prime amplification, or a clamping probe. Using serial dilutions of mutant DNA, rhPCR had a high detection capability limit of boPCR was as low as 0.1% mutant copies (deletion in exon 19) in a background of wild-type copies. The following primer sequences were used: Forward, /5Biosg/CTC TCT CTG TCA TAG GGA CTC TGG ATC and reverse, /5Biosg/CAT GGA CCC CCA CAC AGC AAA G. For the amplification, the 25 μL reaction-solution contained 0.63 unit of Taq DNA Polymerase and Uracil DNA Glycosylase, 20 μL of 1.25 × boPCR Buffer (Final 2.5 mM Mg2+), 0.2 mM of each dNTP and 0.6 mM dUTP, 0.1 to 0.2 μM of primers, and blocking oligo were used. The PCR were performed on GeneAmp9700 system (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies) with followed parameter: UDG reaction at 40 °C for 10 min and primary denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 55 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s and at 60 °C for 30 s, and 94 °C for 10 min, finally holding at 72 °C.

Detection of EGFR mutation using plasma DNA

Plasma DNA was obtained from patients at baseline, weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, and at disease progression. Three types of clinically relevant EGFR mutations (exon 19 deletion, exon 20 Thr790Met [T790 M] and exon 21 L858R) were analyzed using plasma cfDNA with multiplexed, pico-droplet digital PCR assay (RainDrop system, RainDance Technologies, Billerica, MA) [24, 25]. Positivity of cfDNA was defined as mutant allele event/frequency of exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R, or exon 20 T790 M above the cutoff by digital PCR in plasma. Plasma mutant allele frequency (MAF) was calculated by dividing the number of copies of the mutant alleles by the total number of copies of the alleles at the specific locus.

Statistical analysis

PFS was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank tests. Proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Data were analyzed using JMP 13 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

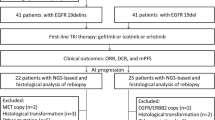

Fifty-seven patients were registered in the parental WJOG 8114LTR study. All patients had EGFR-sensitizing mutations, and 29 (50.9%) and 28 (49.1%) patients had exon 19 deletion and L858R, respectively (Fig. 1). All patient backgrounds and patients with tissue exon 19 deletion are shown in Table 1. Among patients with tissue exon 19 deletion, sixteen (55.2%) and 13 patients (44.8%) were male/female, respectively. Fifteen patients (51.7%) had stage IV disease, and seventeen patients (58.6%) had history of smoking. Performance status (PS) of all patients were either 0 or 1. Concerning exon 19 deletion subgroup, tissue specimens and/or blood samples of three patients were unavailable because of rapid progression before administration of afatinib and tissue insufficiency. We then analyzed data of 26 patients whose tumor tissue and plasma cfDNA were available in this study. Of these patients, thirteen (50.0%) were positive for plasma mutated EGFR at baseline blood draw (Fig. 1). These exon 19 deletion tumors included seven different variants (Table 2). The most common was p.E746_A750delELREA (n = 13, 50.0%), followed by different nucleotide variant of p.E746_A750delELREA (n = 4, 15.4%), p.L747_T751delLREAT (n = 4, 15.4%), p.E746_S752 > V (n = 2, 7.7%). All but one bound the amino acid residues L747 to E749 (LRE), 22 patients (84.6%) and 1 patient (3.8%) had short in-frame deletions (15–18 nucleotides) and macrodeletion (more than 20 nucleotides), respectively. This incidence and distribution was similar to those of COSMIC database (Table 2, Additional file 1: Table S1) [21].

Subgroup classification of exon 19 deletion molecular variants

Based on previous studies, exon 19 deletion variants were categorized according to several classifications based on the number of deleted nucleotides, on deletion starting codons, and the common in frame deletion [10, 14,15,16,17]. With the classification based on the number of deleted nucleotides, p.E746_A750delELREA and p.L747_T751delLREAT were classified as 15-nucleotide deletion subgroup (15n-del), p.L747_P753 > S was classified as 18-nucleotide deletion subgroup (18n-del) and p.E746_S752 > V and p.E746_T751 > I were classified other mixed insertion/substitution variant subgroup (other/mixed ins/sub) based on the mutation syntax of COSMIC database [21]. p.S752_I759delSPKANKEI, which showed 24 nucleotide deletion (macrodeletion) was also classified to other/mixed ins/sub subgroup. Ultimately, twenty-one patients (80.8%) were classified into 15n-del, one patient (3.8%) into 18n-del, and four patients (15.4%) into other/mixed ins/sub subgroups (Table 3). Concerning deletion starting codon classification, twenty (76.9%) and five patients (19.2%) whose deletion starting codon was E746 and L747 were classified into E746 and L747 subgroups, respectively. E746 and L747 subgroups included the amino acid residues LRE, therefore 25 patients (96.2%) were classified into LRE and one patient (3.8%) into non-LRE subgroup (Table 3). On the other hand, all 15n-del and 18n-del belonged to the starting codon E746 or E747 subgroups (Table 2). Similar to COSMIC report, the most frequently detected exon 19 deletion variant was p.E746_A750delELREA and 17 patients (65.4%) were classified into “ELREA” subgroup (Table 3).

Association of EGFR exon 19 subtypes and clinical outcome

At the time of data cutoff, the overall response rate (RR) to afatinib monotherapy was 84.6% of the patients with exon 19 deletion. As shown in Fig. 2, each molecular variant of exon 19 deletions showed good response. As already reported, median PFS was 14.2 months in the parental WJOG 8114LTR study [19]. Subgroup analyses of PFS according to different classifications were then performed. Shown in the swimmer plot, 12 patients (60.0%) with the starting codon L746 and five patients (100.0%) with L747 were still on afatinib treatment, respectively (Fig. 3). Their Kaplan-Meier curves showed no difference of PFS (p = 0.1691) (Fig. 4a). On the other hand, 15 patients (71.4%) with 15 nucleotide deletion and one patient (25.0%) with other nucleotide deletion (other/mixed ins/sub) were still on the treatment and 15n-del subgroup showed significantly longer PFS than other/mixed ins/sub subgroup (p = 0.0244). The number of the patients who had p.E746_S752 > V, p.S752_I759 > del SPKANKEI was small, however, they tended to show shorter PFS, and it led to shorter PFS in other/mixed ins/sub subgroup (Figs. 3 and 4b). PFS of “ELREA” subgroup was similar to non-ELREA (p = 0.7442) (Additional file 2: Figure S1). As mentioned before, plasma cfDNA mutation positivity and its alteration during afatinib were suggested to be good prognostic markers of afatinib in the parental study WJOG 8114LTR [18, 19]. In this exon 19 deletion cohort, at baseline thirteen patients (50.0%) were positive for mutated EGFR cfDNA, and three patients (11.5%) were positive at four weeks. The swimmer plot suggested that the cfDNA negative patients at baseline and the patients whose baseline positive cfDNA subsequently turned negative tended to have longer PFS (Fig. 3). However, presence of cfDNA at baseline as well as at four weeks did not show statistically significant effects on PFS (p = 0.7452, p = 0.4609, respectively) (Additional file 3: Figure S2a, b). Concerning plasma MAF, no clear trend was found in the association between plasma MAF and treatment efficacy. Some patients with higher MAF (more than 10%) before treatment (patient #8: 91.4%, patient #40: 31.0%, patient #47: 32.8%, patient #50: 34.0%), and all but one showed longer PFS (Fig. 3). PFS of the patients with lower MAF, meanwhile, was inconsistent. Multivariate analysis which took into account these factors did not show any factors to predict better prognosis on afatinib monotherapy (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Waterfall plots of overall response rate according to different exon 19 deletion molecular variants (n = 26). The numbers on the X-axis are case numbers. A dashed line means 30% decline of tumor volume; partial response. 15n-del: 15-nucleotide deletion subgroup; 18n-del: 18-nucleotide deletion subgroup; other: other/ mixed insertion/substitution variant subgroup

Swimmer plots of Progression-free survival according to different exon 19 deletion molecular variants (n = 26). Arrows on the right end of the bars indicate ongoing response. Quadrangles on each bar represent plasma cfDNA collection. Black-fill and blank represent positive and negative for plasma cfDNA (exon 19 deletion)

Progression-free survival for patients with exon 19 deletion according to different subtype classifications (n = 25). a Classification with deletion starting codon (n = 25). A patient with the starting codon S752 was excluded because of only one patient was in this subgroup. Any patients with the starting codon L747 did not experience disease progression at the data cut-off date. b Classification with the number of deleted nucleotides (n = 25). Other/mixed insertion/substitution subgroup includes microdeletion (24n-del) and insertion/substitution. A patient with 18 nucleotide deletion was excluded because of only one patient was in this subgroup. *Other/mixed ins/sub: other/mixed insertion/substitution subgroup

Discussion

Exon 19 deletion and L858R point mutation activate somatic mutations in EGFR, and they frequently contribute to structural changes of EGFR tyrosine kinase domains which might be responsible for their different sensitivities to EGFR-TKIs [12]. Mentioned above, exon 19 deletion consists of several molecular variants. In this study, we evaluated the impact of exon 19 deletion molecular variants on sensitivity to first line afatinib monotherapy.

According to COSMIC database, the most frequent molecular variant was p.E746_A750delELREA, followed by p.L747_P753 > S, p.L747_T751delLREAT and p.L747_A750 > P (Additional file 1: Table S1) [21]. While these variants almost always include LRE area, other variants aside from LRE, such as p.S752_I759delSPKANKEI, were also identified [21]. The tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR consists of the N-lobe and the C-lobe. The frame-shift alterations of exon 19 deletion mutations often happen near the C-helix within the N-lobe because of its fragility. Correct positioning of C-helix is required for proper tyrosine kinase activation, and these frame-shift alterations contribute to conformational changes of the tyrosine kinase domain. Each molecular variant appears to have provided specific structural or surface potential changes of EGFR, this might result in variant specific downstream signaling activities [12, 13, 16, 26,27,28]. Ogasawara et al. recently reported that a single codon deletion E746del could induce transformation of the C-terminal domain of EGFR in 3-D structure analysis. The mutant was more kinetically activated and possessed altered electrostatic surface potential of gefitinib binding sites, which preceded much more potent inhibition by gefitinib than wild-type EGFR, and its interaction with gefitinib was similar to common deletion, such as p.E746_A750delELREA [28]. Improta et al. showed that uncommon exon 19 deletion mutations, such as complex deletions with insertion, macrodeletions and duplications also had important structural changes involving the C-helix. Such mutations did not have the same sensitivities to EGFR-TKI [13]. Hence, a single codon deletion as well as complex deletion and microdeletion harbor their own structural conformations which might introduce different sensitivities to EGFR-TKIs [12, 13, 16, 26,27,28]. Even though it remains hypothetical owing to the small number of events, afatinib is an irreversible EGFR-TKI which has broader and more durable inhibitory potencies than those of the first generation EGFR-TKIs, such as gefitinib. In our present study, some exon 19 deletion molecular variants that have specific structural changes of EGFR may provide different impacts on the efficacy of irreversible EGFR-TKI. This could result in different sensitivities between patients harboring different exon 19 variants.

Several reports discuss the similar influences of exon 19 deletion variants on the patients with various stages and treatment lines of different EGFR-TKIs to date (Additional file 1: Table S3) [10, 14,15,16,17]. These reports employed several classifications including by the deletion starting codon and by the number of deleted nucleotides. Concerning the starting codon classification, Lee et al. and Kaneda et al. concluded that E746 had longer PFS than E747, although other reports did not [10, 14,15,16,17]. Regarding the number of deleted codons, only Lee et al. reported that 15n-del revealed longer PFS than 18n-del. They also reported that complex deletions with insertion or substitution had much better PFS, but Kaneda et al. stated the opposite conclusion [15, 16]. In our report, according to classification by the number of deleted codons, 15n-del showed longer PFS than complex and 24n-del. This result was contrary to the results of Lee et al. but consistent with the results of Kaneda et al. [15, 16] Despite the preferable response of 15n-del to afatinib in the present study, some patients with 15n-del still showed poor response. Similar phenomenon was reported in the patients that had EGFR-TKI-sensitizing mutations in previous studies [29]. Co-occurring mutations may confer poor response to afanitib monotherapy despite the presence of 15n-del. Additional comprehensive biomarker analysis may help to explore mechanisms of resistance to afatinib, e.g. MET amplification, BRAF V600E, and small cell transformation [ 30].

Previous reports and parental analysis of this study conversely suggest that detection of plasma-mutated DNA may be a good prognostic marker candidate [19, 31, 32]. With our comparatively small subset, however, similar prognostic impacts were not obtained. Furthermore, concerning plasma MAF, there was no clear correlation between plasma MAF and treatment efficacy.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that collected tissue samples to detect exon 19 deletion molecular variants centrally and to evaluate their influence on the first line afatinib monotherapy. The small sample size is a considerable limitation of this study, so further data accumulation and detailed analyses of the molecular variants are still needed to more fully understand the actual difference of sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs. It would be greatly advantageous for upcoming personalized medicine.

Conclusion

Understanding differential prognosis of the molecular variants of exon 19 deletion might lead us to select more appropriate treatment using EGFR-TKIs that allow better patient outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due patients right of confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Del19:

-

Exon 19 deletion

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ELREA:

-

Glutamic acid-746 (E746) to alanine-750 (A750)

- LRE:

-

Leucine-747 (L747) to glutamic acid-749 (E749)

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- RR:

-

Response rate

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

References

Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O'Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–34.

Yang JC, Sequist LV, Geater SL, Tsai CM, Mok TS, Schuler M, et al. Clinical activity of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring uncommon EGFR mutations: a combined post-hoc analysis of LUX-lung 2, LUX-lung 3, and LUX-lung 6. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:830–8.

Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene and related genes as determinants of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sensitivity in lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1817–24.

Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–500.

Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Sequist LV, Lindeman N, Holmes AJ, Joshi VA, et al. Exon 19 deletion mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with prolonged survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3908–14.

Riely GJ, Pao W, Pham D, Li AR, Rizvi N, Venkatraman ES, et al. Clinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 and exon 21 mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:839–44.

Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, Feng J, Lu S, Huang Y, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:213–22.

Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M, Sebastian M, Popat S, Yamamoto N, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-lung 3 and LUX-lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:141–51.

Gazdar AF. Activating and resistance mutations of EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer: role in clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28(Suppl 1):S24–31.

Sutiman N, Tan SW, Tan EH, Lim WT, Kanesvaran R, Ng QS, et al. EGFR mutation subtypes influence survival outcomes following first-line Gefitinib therapy in advanced Asian NSCLC patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:529–38.

Gazdar AF, Shigematsu H, Herz J, Minna JD. Mutations and addiction to EGFR: the Achilles 'heal' of lung cancers? Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:481–6.

Kumar A, Petri ET, Halmos B, Boggon TJ. Structure and clinical relevance of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1742–51.

Improta G, Zupa A, Natalicchio MI, Sisinni L, Marinaccio A, Bozza G, et al. Uncommon frame-shift exon 19 EGFR mutations are sensitive to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2018;35:28.

Chung KP, Wu SG, Wu JY, Yang JC, Yu CJ, Wei PF, et al. Clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancers harboring different exon 19 deletions in EGFR. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3470–7.

Lee VH, Tin VP, Choy TS, Lam KO, Choi CW, Chung LP, et al. Association of exon 19 and 21 EGFR mutation patterns with treatment outcome after first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:1148–55.

Kaneda T, Hata A, Tomioka H, Tanaka K, Kaji R, Fujita S, et al. Possible differential EGFR-TKI efficacy among exon 19 deletional locations in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86:213–8.

Su J, Zhong W, Zhang X, Huang Y, Yan H, Yang J, et al. Molecular characteristics and clinical outcomes of EGFR exon 19 indel subtypes to EGFR TKIs in NSCLC patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:111246–57.

Akamatsu H, Koh Y, Morita S, Fujimoto D, Okamoto I, Bessho A, et al. A Phase II, Liquid Biopsy Study Using Digital PCR in EGFR Mutated, Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Afatinib (WJOG 8114LTR). J Thoracic Onc. 2017;12 Issue 1:S1234.

Akamatsu H, Koh Y, Okamoto I, Fujimoto D, Bessho A, Azuma K, et al. Clinical significance of monitoring EGFR mutation in plasma using multiplexed digital PCR in EGFR mutated patients treated with afatinib (West Japan oncology group 8114LTR study). Lung Cancer. 2019;131:128–33.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47.

COSMIC v85. https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic. Accessed 7 Nov 2018.

Dunbar SA. Applications of Luminex xMAP technology for rapid, high-throughput multiplexed nucleic acid detection. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;363:71–82.

Hisamatsu Y, Kenmotsu H, Akamatsu H, Serizawa M, Wakuda K, Imai H, et al. Plasma epidermal growth factor receptor mutation analyses in Japanese advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients harboring EGFR mutation by RNase H-dependent PCR and Bloking oligo dependent PCR methods. Annals Oncol. 2014;25 suppl_4:iv58–84.

Watanabe M, Kawaguchi T, Isa S, Ando M, Tamiya A, Kubo A, et al. Ultra-sensitive detection of the pretreatment EGFR T790M mutation in non-small cell LungCancer patients with an EGFR-activating mutation using droplet digital PCR. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3552–60.

Watanabe M, Kawaguchi T, Isa SI, Ando M, Tamiya A, Kubo A, et al. Multiplex ultrasensitive genotyping of patients with non-small cell lung Cancer for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations by means of Picodroplet digital PCR. EBioMedicine. 2017;21:86–93.

Politi K, Lynch TJ. Two sides of the same coin: EGFR exon 19 deletions and insertions in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1490–2.

Marchetti A, Del Grammastro M, Filice G, Felicioni L, Rossi G, Graziano P, et al. Complex mutations & subpopulations of deletions at exon 19 of EGFR in NSCLC revealed by next generation sequencing: potential clinical implications. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42164.

Ogasawara M, Nakamura Y, Morikawa N, Nitanai H, Moriguchi S, Chiba R, et al. Analysis of a single-codon E746 deletion in exon 19 of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:1019–29.

Park K, Tan EH, O'Byrne K, Zhang L, Boyer M, Mok T, et al. Afatinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment of patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (LUX-lung 7): a phase 2B, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:577–89.

Nakamura T, Nakashima C, Komiya K, Kitera K, Hirai M, Kimura S, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to afatinib clarified with liquid biopsy. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209384.

Li X, Ren R, Ren S, Chen X, Cai W, Zhou F, et al. Peripheral blood for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation detection in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl Oncol. 2014;7:341–8.

Wu YL, Sequist LV, Hu CP, Feng J, Lu S, Huang Y, et al. EGFR mutation detection in circulating cell-free DNA of lung adenocarcinoma patients: analysis of LUX-lung 3 and 6. Br J Cancer. 2017;116:175–85.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the patients, clinical investigators and staff for their contributions to this study. We acknowledge proofreading and editing by Benjamin Phillis at the Clinical Study Support Center, Wakayama Medical University.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Boehringer Ingelheim, that did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NT performed the analysis and wrote the article, YK, HA & NY supported the article writing and analysis, DF, IO, KN, TH, FI & SM performed the analysis and proof read the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Wakayama Medical University (Reference number: 1558), and its members were as follows: Yoshito Ihara; Seiji Makino; Shigemitsu Takeyama; Shinichi Murata; Tatsuya Takeshita; Takashi Akamizu; Nobuyuki Yamamoto; Yoshi Tsukiyama; Tsukasa Hotta; Koichi Nakanishi; Mariko Shikamura; Masako Miyajima; Akihiko Iwahara; Toshimi Matsubara; Mitsuko Okamoto; Aiko Kitano. All participating centers in alphabetical order are listed as follows: Aichi Cancer Center; Gifu Municipal Hospital; Institute of Biomedical Research and Innovation; Izumi Municipal Hospital; Japanese Red Cross Okayama Hospital; Kindai University; Kishiwada City Hospital; Kobe University Hospital; Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital; Kurashiki Central Hospital; Kurume University Hospital; Kyushu University; Nagoya City University Hospital; National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center; National Hospital Organization Nagoya Medical Center; Osaka City General Hospital; Osaka International Cancer Institute; Osaka Medical College Hospital; Wakayama Medical University. The protocol was also approved by the ethics committees of all participating centers. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

NT has no conflict of interests to declare. YK receives honoraria and research funding from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim. HA receives honoraria and research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, DF receives honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim. IO receives research grant and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim. KN reports research funding, honoraria and consulting or advisor role from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd. TH reports receiving research grant and personal fees from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim. FI receives honoraria and research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. SM receives research grant and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim. NY receives research grant and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Exon 19 deletion variant list. These molecular variants were the first twenty of the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) frequencies. #At 07/11/2018. Table S2. Multivariate analysis of progression-free survival with the patients with exon 19 deletions receiving afatinib (n = 24). A patient with the starting codon S752 and another patient with 18 nucleotide deletion were excluded because only one patient was in each subgroup. Table S3. Previous reports of non–small cell lung cancers with different exon 19 deletions molecular variants and their clinical outcomes. *referred to 15n-del (ELREA).

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Progression-free survival for patients according to different subtypes of exon 19 deletions (n = 26). ELREA or not.

Additional file 3:

Figure S2.Progression-free survival for patients with exon 19 deletion according to presence of mutated plasma EGFR. a) At baseline (n = 26), b) At 4 weeks (n = 26). del19, exon 19 deletion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tokudome, N., Koh, Y., Akamatsu, H. et al. Differential significance of molecular subtypes which were classified into EGFR exon 19 deletion on the first line afatinib monotherapy. BMC Cancer 20, 103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-6593-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-6593-1