Abstract

Background

Contradictory and limited data are available about the presentation and outcomes of patients with RET-fusion positive metastatic NSCLC as compared to patients without RET fusions. This observational study utilizing a linked electronic health records (EHR) database to genomics testing results was designed to compare characteristics, tumor response, progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) outcomes by RET fusion status among patients with metastatic NSCLC treated with standard therapies.

Methods

Adult patients with metastatic NSCLC with linked EHR and genomics data were eligible who received systemic anti-cancer therapy on or after January 1, 2011. Adjusted, using all available baseline covariates, and unadjusted analyses were conducted to compare tumor response, PFS and OS between patients with RET-fusion positive and RET-fusion negative disease as detected by next-generation sequencing. Tumor response outcomes were analysed using Fisher’s exact test, and time-to-event analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

There were 5807 eligible patients identified (RET+ cohort, N = 46; RET- cohort, N = 5761). Patients with RET fusions were younger, more likely to have non-squamous disease and be non-smokers and had better performance status (all p < 0.01). In unadjusted analyses, there were no significant differences in tumor response (p = 0.17) or PFS (p = 0.06) but OS was significantly different by RET status (hazard ratio, HR = 1.91, 95% CI:1.22–3.0, p = 0.005). There were no statistically significant differences by RET fusion status in adjusted analyses of either PFS or OS (PFS HR = 1.24, 95% CI:0.86–1.78, p = 0.25; OS HR = 1.52, 95% CI: 0.95–2.43, p = 0.08).

Conclusions

Patients with RET fusions have different baseline characteristics that contribute to favorable OS in unadjusted analysis. However, after adjusting for baseline covariates, there were no significant differences in either OS or PFS by RET status among patients treated with standard therapy prior to the availability of selective RET inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The treatment of patients diagnosed with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is increasingly determined by the presence or absence of actionable biomarkers. This is a change that has occurred since 2009, when the first differentiation in treatment was based on tumor histology [1]. Since then, therapies have been approved by regulatory bodies across the world that target epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1), v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) exon 14, neurootrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) and most recently, rearranged during transfection (RET) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Selpercatinib was approved for use in the U.S. in May 2020 for patients with RET-fusion positive non-small cell lung cancer, RET-fusion positive thyroid cancer, or RET-mutation positive meduallary thyroid cancer. This approval was based on a single-arm phase I/II trial, LIBRETTO-001, which demonstrated overall tumor response rates of 85 and 64% for patients with RET-fusion positive NSCLC who were treatment naïve and previously treated, respectively [17, 18]. Response rates were similar for patients with RET altered thyroid (treatment naïve, 100%; previously treated, 79%) and medullary thyroid cancers (no prior multikinase inhibitors [MKIs], 73%, previously treated with MKIs, 69%) [17]. The characterization of real-world demographics and outcomes in the setting of EGFR, ROS1, BRAF or ALK alterations been investigated in multiple large cohort studies in NSCLC [19,20,21,22,23]. In the case of RET fusions, however, less is known. Contradictory and limited data are available about the presentation and outcomes of patients with RET fusion-positive metastatic NSCLC.

Many studies of patients with RET fusions focus on or include many with early stage disease, limiting the ability to apply the findings to patients eligible for RET-directed therapy [24, 25]. There are several common features observed among patients with RET fusions in publications to date, such as the prevalence of non-smoking status and younger age at diagnosis [26,27,28,29,30,31]. However, there have been other small studies that have not observed significant differences in these factors [32]. Each of these studies included less than 20 patients with RET fusion-positive disease. Several larger studies have similarly described patients with RET fusions, but no comparison group was available [30, 33,34,35].

Other studies have tried to estimate the survival outcomes among patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) estimates in a meta-analysis were based on unadjusted analyses and found no difference in either OS (n = 75 patients with RET fusions) or PFS (n = 24 with RET fusions) by RET fusion status [36].

The outcomes of these studies remain inconclusive due to small sample [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] and due to the lack of a comparison group or failure to adjust for baseline prognostic factors [34,35,36]. Adjustment for these factors is critical in that multiple prognostic factors are known to differ among patients with RET fusions based on these initial descriptive studies (e.g. age, gender, smoking status, line of therapy, treatment received). Because of these issues, there remains uncertainty regarding the outcomes of patients treated with standard therapy who are diagnosed with RET fusion-positive NSCLC related to the broader cohort of patients without these fusions.

This observational study was designed to compare the baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes among patients with metastatic NSCLC by RET fusion status treated in standard practice settings prior to the approval of selective RET inhibitors.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective observational study utilized the Flatiron-Foundation Medicine Clinico-Genomics database (CGDB) [37]. The CGDB is a combination of Flatiron Health’s longitudinal database containing electronic health record (EHR) data from over 265 cancer clinics (approximately 800 sites of care) including more than 2 million cancer patients in the US linked to comprehensive genomic profiling data obtained from Foundation Medicine, Inc. (FMI). The de-identified patient-level clinical data from the EHR includes structured data (e.g., laboratory values, prescribed drugs) in addition to unstructured data collected via technology-enabled chart abstraction from physician’s notes and other unstructured documents (e.g., detailed biomarkers). De-identified patient-level genomic data from FMI includes specimen features (e.g., tumor mutation burden, pathologic purity), alteration-level details (e.g., genomic position, reference and alternate alleles, mutant allele count, minor allele frequency), and therapeutic recommendations that were reported to the clinician at the time of testing. Death dates are entered as month and year to protect confidentiality and obtained from three sources: EHR; social security death index; and published obituary notices. All data are de-identified and provisions are in place to prevent re-identification in order to protect patients’ confidentiality. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval with waiver of informed consent (Copernicus Group IRB) was obtained by Flatiron Health prior to the provision of these datasets and conduct of this study.

Eligibility criteria

Patients with metastatic NSCLC identified in the CGDB were eligible for this study if they were age 18 years or older at the time of diagnosis, and who received their initial systemic anti-cancer therapy within 180 days of metastatic diagnosis. Patients only treated with adjuvant or neoadjuvant systemic therapy were excluded to avoid the inclusion of patients with early stage disease with missing stage data, but patients who were diagnosed with earlier stage disease who progressed were included if they received systemic therapy within 180 days after progression. All patients in the CGDB had results of next-generation sequencing (NGS) reported in the database from FMI; the sensitivity and specificity to RET fusions are both very high with NGS-based methods [38,39,40] Patients were required to have initiated the systemic therapy on or after January 1, 2011. Patient follow-up data were available through June 2019 for this study, preceding the availability of selective RET inhibitors. No minimum follow-up time was required after initiation of first-line therapy.

Patient cohorts

Patients were assigned to the RET+ cohort if there was evidence of a fusion with RET recorded at any time in the CGDB. Patients were assigned to the RET- cohort if there was no evidence of a RET fusion in the database.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics, defined at start of first-line therapy, were compared between the RET+ and RET- cohorts using student’s t-test for continuous measures and Chi-squared/Fisher’s exact test for categorical measures. Missing values were reported descriptively and included as a categorical variable in the comparative analyses to avoid losing cases due to missing data. Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize testing and treatment patterns of both cohorts. Duration of treatment was defined from the start of the line of therapy until the last infusion/administration of any drug within that regimen. Due to the high number of treatment regimens used in NSCLC, multiplicity is a concern and pairwise comparisons of individual treatment patterns were not made but all regimens were reported descriptively.

Analyses were conducted to compare tumor response, PFS and OS between the RET+ and RET- cohorts. Tumor response outcomes were analysed using Fisher’s exact test, and best response during the line of therapy was categorized as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) as recorded by the oncologist in the patient record. Additionally, odds ratios were calculated for objective response rate (ORR), which combined both CR and PR, and were analysed among patients with response data recorded using multivariable logistic regression by RET status. Time-to-event analyses (PFS and OS) were conducted using Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards regression from the start of the line of therapy. Baseline covariates in the multivariable regression for the adjusted analysis of PFS and OS included age, sex, race, practice type (academic or community), body weight, body mass index (BMI), stage at initial diagnosis, tumor histology, smoking status, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, genomic alterations, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, PD-L1 expression (positive = > 1% staining versus negative), initial treatment regimen (checkpoint inhibitor use yes/no), and reported metastatic sites.

Secondary analyses compared tumor response and evaluated adjusted and unadjusted PFS and OS from the start of first-line therapy among the subgroup of patients in both cohorts who received first-line pembrolizumab + pemetrexed + platinum (pembro + PC, the regimen evaluated in Keynote [KN]-189), which has recently become a standard of care for patients with NSCLC [41]. For the KN-189 regimen analyses, carboplatin and cisplatin were considered interchangeable.

Sensitivity analyses

Post-hoc sensitivity analyses explored variables reported differentially in the FMI versus EHR datasets (i.e. PD-L1 status). In the CGDB database, PD-L1 is evaluated using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and is assigned categorical groupings so that < 1% staining is negative, 1–49% is low positive, and 50% or greater is considered high positive. In the EHR data, PD-L1 is coded as either positive or negative by abstractors using either percent staining (in the database, any staining > 1% is entered as ‘positive’) or if positivity is explicitly stated in the report in the patient record. Primary analyses combined all data to minimize missingness; sensitivity analyses limited the evaluation of PD-L1 status to FMI test results. Sensitivity analyses also evaluated the influence of several assumptions in the covariates used in the adjusted regression models: 1) excluding missing data; 2) collapsing checkpoint inhibitor use to none, monotherapy or combination therapy regimens; 3) including other targeted agents as a unique drug category and 4) excluding the prior therapy grouping strategy.

Results

Patient characteristics

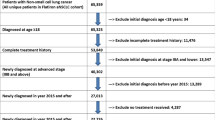

A total of 5807 patients were identified that met the eligibility criteria (RET+ cohort, N = 46; RET- cohort, N = 5761). A summary of the cohort identification is included in Fig. 1. Of the overall eligible NSCLC cohort, 46 patients (0.8%) had RET fusions.

A summary of the characteristics of patients at the start of first-line therapy (baseline) is provided in Tables 1 and 2. Patients with RET fusions were significantly younger (mean age 62.9 versus 67.2 years, p = 0.004), were more likely to have non-squamous disease (100% versus 79.4%, p = 0.0006), to be non-smokers (63.0% versus 18.1%, p < 0.0001), and had better performance status (p = 0.02). Of note, no patients with RET fusions had ALK, ROS1, KRAS or BRAF positive disease, however, there were three patients with concurrent EGFR mutations where the RET fusion was considered to have been acquired due to resistance to ongoing anti-EGFR therapy. Two patients with RET fusions had an exon 19 mutation (one with a T790M mutation) and one patient had an exon 21 mutation.

PD-L1 status as recorded in EHR prior to initiation of first-line therapy was not recorded among 52.2% (n = 24) of patients in the RET+ cohort and 56.2% (n = 3240) of patients in the RET- cohort. In the EHR data, patients with PD-L1 positive results prior to initiation of first-line therapy were 68.2 and 47.2%, respectively (p = 0.06, Table 2). When limiting the analysis to the IHC-based results from FMI recorded prior to initiation of first-line treatment, patients in the RET+ versus RET- cohorts were high positive (28.6% versus 31.2%), low positive (57.1% versus 28.1%), and negative (14.3% versus 40.7%), p = 0.21. A greater proportion of data were missing (84.8%, n = 39 and 78.4%, n = 4518 of patients in the RET+ and RET- cohorts, respectively) when limiting PD-L1 status to only values reported by FMI IHC prior to initiation of therapy.

Treatment patterns by RET status

The most common regimens used in the first-line setting are presented in Fig. 2 for the RET+ (n = 46) and RET- cohorts (n = 4392). The most common first-line regimens used for patients with non-squamous NSCLC were bevacizumab + carboplatin + pemetrexed (23.9% for the RET+ and 9.8% for the RET- cohort), pembrolizumab + carboplatin + pemetrexed (19.6%, RET+; 14.1% RET-), pemetrexed + carboplatin (13.0% RET+; 16.1% RET-). All other regimens were each used in less than 5% of the RET+ cohort (other than clinical trial participation, which was 6.5% for RET+ and 3.3% of the RET- cohort); these other regimens comprised 37.0% of all RET+ first-line therapies.

Among patients with RET- cancers, carboplatin + paclitaxel was used among 8.7%, pembrolizumab among 7.6%, and erlotinib among 7.1%. The other regimens were each used by less than 5% of the RET- cohort and comprised 36.6% of first-line therapies. Overall, 14 patients (30.4%) in the RET+ cohort and 1702 (29.5%) in the RET- cohort received checkpoint inhibitors in the first line setting. Pembro + PC was used by 9 (19.6%) patients in the RET+ cohort and 665 (11.5%) in the RET- cohort.

There were no patients with squamous NSCLC identified in the RET+ cohort, therefore no summary of treatment patterns by RET status could be reported.

The observed median duration of therapy for patients in the RET+ cohort receiving pembro + PC was 106 days (range 13–512). The observed median duration of therapy for patients receiving pembro + PC in the RET- cohort was 92 days (range 1–748).

Clinical outcomes

There were no significant differences in tumor response in the first-line setting (p = 0.17), for the subgroup who received pembro + PC in the first-line setting (p = 0.15) or to second-line therapy (p = 0.93) by RET fusion status (Table 3). The rate of missing tumor response data was 41.3 and 58.7%, 11.1 and 34.4%, and 39.1 and 49.3% for the RET+ and RET- cohort, respectively for the first-line, first-line pembro + PC, and second-line settings.

As presented in Table 4, unadjusted PFS from the start of first-line therapy was not significantly different by RET fusion status (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.40: 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.0–2.0, p = 0.06). There was a significant difference favoring longer OS for the RET+ cohort in unadjusted analyses (HR = 1.91: 95% CI: 1.2–3.0, p = 0.005). Unadjusted PFS and OS by RET status were not significantly different for patients receiving first-line KN-189 regimen (PFS HR = 1.0; 95% CI: 0.5–2.3, p = 1.0; OS HR = 1.9; 95% CI: 0.48–7.72, p = 0.36). Among those who received pembro + PC, median PFS for the RET+ cohort was 6.6 months (95% CI: 0.4 - not reached) and was 5.7 months (95% CI: 5.0–6.5) for those without RET fusions. Median Table OS was not reached for patients in the RET+ cohort receiving the KN-189 regimen and the CI could not be evaluated but was 14.0 months (95% CI: 12.3–18.5) for patients without RET fusions.

After adjusting for all covariates, no statistically significant differences remained for either PFS (HR = 1.24, 95% CI:0.86–1.78, p = 0.25) or OS (HR = 1.52, 95% CI: 0.95–2.43, p = 0.08) outcomes between the RET+ and RET- cohorts (Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses

When further categorizing drug class as checkpoint inhibitor-based monotherapy versus checkpoint inhibitor-based combination therapy, versus all others, this factor (drug class of first-line therapy) remained similar between RET cohorts (p = 0.78 and p = 0.07 in the PFS and OS analyses, respectively), and did not alter significance of the primary findings for PFS (HR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.86–1.78, p = 0.26) or OS (HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 0.96–2.44, p = 0.08) by RET status. Similarly, further categorization within treatments received to include targeted or biologic agents as an additional group (PFS HR = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.88–1.84, p = 0.20; OS HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 0.98–2.5, p = 0.06) or by excluding prior treatment as a covariate (PFS HR = 1.24, 95% CI: 0.86–1.78, p = 0.26; OS HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 0.95–2.44, p = 0.08) did not alter any of the results. Lastly, the exclusion of missing values in the analysis also did not change the results (PFS HR = 1.10, 95% CI: 067–1.82, p = 0.71; OS HR = 1.47; 95% CI: 0.78–2.75, p = 0.23), Table 4.

Discussion

This large real-world database study of over 5900 patients with NSCLC treated in the US identified 46 (0.8%) patients with a RET fusion. The observed RET fusion rate in this study is comparable to other cohorts of patients, which range from 0.6–1.8% [24, 27, 32, 33, 42, 43]. A number of other studies were limited to patients without other actionable alterations and reported higher prevalence in these cohorts, ranging from 2.2–3.8%, potentially due to the much smaller denominator [25, 28, 44, 45]. Additionally, the inclusion of both patients with and without RET fusions from the same database allows for comparative analyses to be conducted to more accurately characterize differences observed in standard practice with and without this alteration.

There have been inconsistent findings related to differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without RET fusions [25, 28, 32, 36]. Patients with RET fusions in this study were younger (p = 0.004), more likely to be diagnosed with non-squamous cell carcinoma (p < 0.001), nonsmokers (p < 0.0001) and had better performance status (p = 0.01). These findings have been observed previously [24, 26, 36]. However, in this study, stage at diagnosis and sex were not significantly different by RET status. The Flatiron NSCLC database is limited to patients with advanced or metastatic disease; therefore, patients diagnosed with early stage disease who did not progress to a metastatic stage would not be included. Therefore, early stage disease cannot fully be evaluated in this dataset. Differences in sex have also been observed in some studies [24, 28, 36]. This study did not find any differences in sex, but this could also be due to the restriction of the cohort to those patients whose disease had advanced, or due to the non-comparative design of previous studies, which may limit their interpretation [27, 28, 46].

In this study, PD-L1 was used as a covariate for the comparative analyses and limited to data that were recorded prior to initiation of first-line therapy. Therefore, these data are not intended to compare PD-L1 status by RET status, given the exclusion of any variables recorded after treatment initiation. This study demonstrated 68.2% positivity in the EHR and 85.7% in the FMI report for the tests conducted prior to initiation of first-line therapy. Additional work would be needed taking all PD-L1 tests into consideration to evaluate expression levels by RET status.

In the Flatiron Health EHR data record, the presence of metastatic sites is not a fully reliable field as only presence of metastases are recorded. The absence of a metastatic site does not mean that the patient did not have metastases. A chart review study would be needed to better identify metastatic sites and was not the intent to investigate these differences by cohort, but rather to characterize baseline data for covariate adjustment in the outcomes analysis. Therefore, these data should be interpreted with caution.

Patients with and without RET fusions receiving standard non-RET targeted therapies had similar PFS and OS outcomes after adjusting for baseline factors; these similarities were maintained when limited to the KN-189 regimen and when excluding missing variables in sensitivity analysis. This suggests that patients with RET fusions have similar outcomes on standard therapy as their fusion-negative counterparts when adjusting for demographic, clinical and treatment-related factors. While treatment patterns were too heterogeneous to adjust for every regimen, the grouping of treatment classes by three methods made little difference in clinical outcomes. As expected, the inclusion of targeted or biologic therapies was meaningful for improved patient outcomes, but it did not alter the significance of findings in the comparison by RET status. There were no specific regimen differences between the cohorts that might otherwise explain potentially unadjusted factors to explain survival outcomes. Of note, this study included an unselected cohort of patients with NSCLC. Several factors were notable, such as the lack of patients with squamous cell carcinoma or co-existing mutations. The single-arm trial, LIBRETTO-001 reported the outcomes of 105 patients with RET-fusion positive NSCLC. In this study, one patient had squamous cell carcinoma [18]. The current study supports the rarity of RET fusions in squamous NSCLC. Future research may wish to evaluate a more selected cohort for comparison, whereas in this study we focused on all potential differences by cohort, including histology, and then adjusted for those covariates in comparative analyses. The purpose of this study was not to compare to the clinical trial, but rather suggests that real-world data may provide such a data source for an external control arm in future research.

One of the limitations of real-world data is the type of variables recorded. There may be additional important factors that this analysis could not account for due to the lack of certain prognostic variables in EHR. Comorbid conditions, for example, are not available for analysis in the Flatiron datasets, and patient well-being can only be estimated through their reported performance status. Comorbidities are known to have a prognostic effect on clinical outcomes in oncology [47]. Assuming that patients with better performance status and lower age may have fewer comorbidities, the inclusion of comorbid conditions may have further reduced any potential differences by RET status, but this remains unknown and should be further investigated as larger datasets become available that include these data. Additionally, clinical variables such as tumor grade and details on the histological subtypes of non-squamous disease are also lacking in this real-world dataset that could further inform this analysis. While the results were consistent across all subgroups and analyses in this study, the results are limited by the small sample size, particularly for KN-189, and should be further evaluated as testing rates improve and greater numbers of patients with RET fusions become available for study.

The Flatiron CGDB is not a representative sample but is limited to practices in the network and to patients with FMI test results. This cohort is known to have immortal time bias, so the survival estimates from this study will be longer than those in a general population [48]. Since both the RET+ and RET- cohorts experience this issue, the comparative analyses are not impacted by this bias in the current study, but the duration of overall survival outcomes of these cohorts are expected to be longer than what may be observed outside of this dataset. These findings are likely not generalizable to the overall US population.

Due to the rarity of RET fusions among patients with NSCLC, the robust study of the prognostic effect of these fusions remains challenging. It will be important that genomic testing become more widespread to identify fusions and that this factor be subsequently recorded in EHR datasets to enable a more robust study. This study was limited to patients in Flatiron’s CGDB in order to identify RET fusions. There were 8295 patients in this dataset from which eligibility criteria were applied. In the EHR, there are longitudinal data from more than 60,000 patients with advanced or metastatic disease available for study. As RET becomes hard coded into EHR systems, researchers will not have to rely on the linkage to genomics testing results for patient identification and will be able to access larger cohorts directly from EHR data for observational research.

Conclusion

This cohort study evaluated characteristics, treatment patterns and compared clinical outcomes among patients with NSCLC by RET fusion status. The findings confirm the differential characteristics of patients with RET fusions, that contribute to favorable clinical outcomes in the setting of standard non-RET targeted therapies. However, after adjusting for baseline covariates, there remains little evidence that the RET fusion alone contributes to these outcomes. Therapies targeting the RET fusion as a driver in NSCLC may help improve outcomes in this patient population. This study is limited due to small sample size and potential unmeasured confounding and was not designed to evaluate the prognostic effect of the presence of a RET fusion in NSCLC.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study have been originated by Flatiron Health, Inc. These de-identified data may be made available upon request and are subject to a license agreement with Flatiron Health; interested researchers should contact <DataAccess@flatiron.com> to determine licensing terms.

Change history

26 April 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10879-2

Abbreviations

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BRAF:

-

V-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CR:

-

Complete response

- CGDB:

-

Clinico-Genomics database

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- FISH:

-

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- FMI:

-

Foundation Medicine, Inc.

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KN-189:

-

Keynote 189

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

- MET:

-

Mesenchymal-epithelial transition/MET proto-oncogene

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- NTRK:

-

Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- Pembro+PC:

-

Pembrolizumab + pemetrexed + platinum

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death ligand 1

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- RET:

-

Rearranged during transfection

- ROS1:

-

ROS proto-oncogene 1

- Sd:

-

Standard deviation

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- TTD:

-

Time to treatment discontinuation

- US:

-

United States

References

Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, Sugarman K, Blatter J, Peterson P, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two phase III studies. Oncologist. 2009;14(3):253–63.

Bogdanowicz BS, Hoch MA, Hartranft ME. Flipped script for gefitinib: a reapproved tyrosine kinase inhibitor for first-line treatment of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation positive metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2017;23(3):203–14.

Dungo RT, Keating GM. Afatinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2013;73(13):1503–15.

Greig SL. Osimertinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2016;76(2):263–73.

Kazandjian D, Blumenthal GM, Luo L, He K, Fran I, Lemery S, et al. Benefit-risk summary of crizotinib for the treatment of patients with ROS1 alteration-positive, metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21(8):974.

Al-Salama ZT, Keam SJ. Entrectinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2019;79(13):1477–83.

Odogwu L, Mathieu L, Blumenthal G, Larkins E, Goldberg KB, Griffin N, et al. FDA approval summary: dabrafenib and trametinib for the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancers harboring BRAF V600E mutations. Oncologist. 2018;23(6):740.

Larkins E, Blumenthal GM, Chen H, He K, Agarwal R, Gieser G, et al. FDA approval: alectinib for the treatment of metastatic, ALK-positive non–small cell lung cancer following crizotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(21):5171–6.

Markham A. Brigatinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2017;77(10):1131–5.

Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Zhang L, Tang S, Brower M, Fox E, et al. FDA approval: ceritinib for the treatment of metastatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(11):2436–9.

Kazandjian D, Blumenthal GM, Chen H-Y, He K, Patel M, Justice R, et al. FDA approval summary: crizotinib for the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangements. Oncologist. 2014;19(10):e5.

Scott LJ. Larotrectinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2019;79(2):201–6.

NCI. FDA Approves Entrectinib Based on Tumor Genetics Rather Than Cancer Type: National Cancer Institute; 2019 [Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2019/fda-entrectinib-ntrk-fusion.

FDA. RETEVMO (selpercatinib) Prescribing Information 2020 [Available from: http://pi.lilly.com/us/retevmo-uspi.pdf.

FDA. FDA approves selpercatinib for lung and thyroid cancers with RET gene mutations or fusions 2020 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-selpercatinib-lung-and-thyroid-cancers-ret-gene-mutations-or-fusions.

FDA. FDA Approves First Targeted Therapy to Treat Aggressive Form of Lung Cancer 2020 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-targeted-therapy-treat-aggressive-form-lung-cancer.

FDA. Selpercatinib (RETEVMO) Package Insert 2020 [Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213246s000lbl.pdf.

Drilon A, Oxnard GR, Tan DS, Loong HH, Johnson M, Gainor J, et al. Efficacy of Selpercatinib in RET fusion–positive non–small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):813–24.

Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, Digumarthy SR, Costa DB, Heist RS, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4247.

Tokumo M, Toyooka S, Kiura K, Shigematsu H, Tomii K, Aoe M, et al. The relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and clinicopathologic features in non–small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(3):1167–73.

Zhu Q, Zhan P, Zhang X, Lv T, Song Y. Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with ROS1 fusion gene in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Translational lung cancer research. 2015;4(3):300.

Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, Grazia Sciarrotta M, Guetti L, Chella A, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3574–9.

Tissot C, Couraud S, Tanguy R, Bringuier P-P, Girard N, Souquet P-J. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. Lung Cancer. 2016;91:23–8.

Tsuta K, Kohno T, Yoshida A, Shimada Y, Asamura H, Furuta K, et al. RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung carcinoma: a clinicopathological and molecular analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(6):1571–8.

Michels S, Scheel AH, Scheffler M, Schultheis AM, Gautschi O, Aebersold F, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of RET rearranged lung cancer in European patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):122–7.

Kohno T, Ichikawa H, Totoki Y, Yasuda K, Hiramoto M, Nammo T, et al. KIF5B-RET fusions in lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):375–7.

Song Z, Yu X, Zhang Y. Clinicopathologic characteristics, genetic variability and therapeutic options of RET rearrangements patients in lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2016;101:16–21.

Dugay F, Llamas-Gutierrez F, Gournay M, Medane S, Mazet F, Chiforeanu DC, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of ROS1-and RET-rearranged NSCLC in caucasian patients: data from a cohort of 713 non-squamous NSCLC lacking KRAS/EGFR/HER2/BRAF/PIK3CA/ALK alterations. Oncotarget. 2017;8(32):53336.

Dudnik E, Bshara E, Grubstein A, Fridel L, Shochat T, Roisman LC, et al. Rare targetable drivers (RTDs) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): outcomes with immune check-point inhibitors (ICPi). Lung Cancer. 2018;124:117–24.

Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, Mhanna L, Cortot A, Mezquita L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1321–8.

Guisier F, Dubos-Arvis C, Viñas F, Doubre H, Ricordel C, Ropert S, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with advanced Non Small Cell Lung Cancer with BRAF, HER2 or MET mutation or RET-translocation. GFPC 01–2018. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2020.

Pan Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Hu H, Wang L, Li H, et al. ALK, ROS1 and RET fusions in 1139 lung adenocarcinomas: a comprehensive study of common and fusion pattern-specific clinicopathologic, histologic and cytologic features. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(2):121–6.

Zhang K, Chen H, Wang Y, Yang L, Zhou C, Yin W, et al. Clinical characteristics and molecular patterns of RET-rearranged lung cancer in Chinese patients. Oncology Research Featuring Preclinical and Clinical Cancer Therapeutics. 2019;27(5):575–82.

Sireci A, Morosini D, Rothenberg S. P1. 01–101 Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in RET Fusion Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. J Thor Oncol. 2019;14(10):S401.

Offin M, Guo R, Wu SL, Sabari J, Land JD, Ni A, et al. Immunophenotype and response to immunotherapy of RET-rearranged lung cancers. JCO precision oncology. 2019;3.

Cong X-F, Yang L, Chen C, Liu Z. KIF5B-RET fusion gene and its correlation with clinicopathological and prognostic features in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. OncoTargets and therapy. 2019;12:4533.

Agarwala V, Khozin S, Singal G, O’Connell C, Kuk D, Li G, et al. Real-world evidence in support of precision medicine: clinico-genomic cancer data as a case study. Health Aff. 2018;37(5):765–72.

Ferrara R, Auger N, Auclin E, Besse B. Clinical and translational implications of RET rearrangements in non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(1):27–45.

Naidoo J, Drilon A. Molecular diagnostic testing in non-small cell lung cancer. American Journal of Hematology/Oncology®. 2014;10:4.

Garinet S, Laurent-Puig P, Blons H, Oudart J-B. Current and future molecular testing in NSCLC, what can we expect from new sequencing technologies? J Clin Med. 2018;7(6):144.

Gadgeel S, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Speranza G, Esteban E, Felip E, Dómine M, et al. Updated Analysis From KEYNOTE-189: Pembrolizumab or Placebo Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum for Previously Untreated Metastatic Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;19:03136.

Takeuchi K, Soda M, Togashi Y, Suzuki R, Sakata S, Hatano S, et al. RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):378.

Suehara Y, Arcila M, Wang L, Hasanovic A, Ang D, Ito T, et al. Identification of KIF5B-RET and GOPC-ROS1 fusions in lung adenocarcinomas through a comprehensive mRNA-based screen for tyrosine kinase fusions. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(24):6599–608.

Byeon S, Lee B, Park W-Y, Choi Y-L, Jung HA, Sun J-M, et al. Benefit of Targeted DNA Sequencing in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients Without EGFR and ALK Alterations on Conventional Tests. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2019.

Yokota K, Sasaki H, Okuda K, Shimizu S, Shitara M, Hikosaka Y, et al. KIF5B/RET fusion gene in surgically-treated adenocarcinoma of the lung. Oncol Rep. 2012;28(4):1187–92.

Tan AC, Seet AO, Lai GG, Lim TH, Lim AS, San Tan G, et al. Molecular Characterization and Clinical Outcomes in RET-Rearranged NSCLC. J Thor Oncol. 2020.

Tammemagi CM, Neslund-Dudas C, Simoff M, Kvale P. Impact of comorbidity on lung cancer survival. Int J Cancer. 2003;103(6):792–802.

Singal G, Miller PG, Agarwala V, Li G, Kaushik G, Backenroth D, et al. Association of patient characteristics and tumor genomics with clinical outcomes among patients with non–small cell lung cancer using a clinicogenomic database. Jama. 2019;321(14):1391–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained or utilized in the conduct of this study or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LMH and AS conceptualized the research project and wrote the study protocol. YH and YEZ were involved in the design of the study and analysis and interpretation of data. LMH was responsible for the writing of the manuscript. LMH, YH, YEZ, NRB and AS each interpreted the final data, contributed to the intellectual content of the final written manuscript, and provided substantial content to the final version. LMH, YH, YEZ, NRB and AS have each read and approved the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No human subjects were involved in this study. This study utilized a de-identified database, which according to the US Code of Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46.102(e) (1)) is not considered human subjects research. Data used for this study were licensed for use from Flatiron Health, Inc.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

LMH, YH, YEZ and NRB are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. AS is an employee of Loxo Oncology, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hess, L.M., Han, Y., Zhu, Y.E. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with RET-fusion positive non-small lung cancer in real-world practice in the United States. BMC Cancer 21, 28 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07714-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07714-3