Abstract

Background

Treatment options for advanced thyroid cancer refractory to standard therapies are limited. The safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab were evaluated in patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer expressing programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1).

Methods

Patients with advanced thyroid cancer were enrolled in the nonrandomized, phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 trial conducted to evaluate safety and antitumor activity of the anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibody pembrolizumab in advanced solid tumors. Key eligibility criteria were advanced papillary or follicular thyroid cancer, failure of standard therapy, and PD-L1 expression in tumor or stroma cells (assessed by immunohistochemistry). Pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg was administered every 2 weeks up to 24 months or until confirmed progression or intolerable toxicity. The primary endpoint was objective response rate (ORR) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1.

Results

Twenty-two patients were enrolled: median age was 61 years; 59% were women; and 68% had papillary carcinoma. Median follow-up was 31 months (range, 7–34 months). Treatment-related adverse events were observed in 18 (82%) patients; those occurring in ≥15% of patients were diarrhea (n = 7) and fatigue (n = 4). One grade ≥ 3 treatment-related adverse event occurred (colitis, grade 3); no treatment-related discontinuations or deaths occurred. Two patients had confirmed partial response, for an ORR of 9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1–29%); response duration was 8 and 20 months. Median progression-free survival was 7 months (95% CI, 2–14 months); median overall survival was not reached (95% CI, 22 months to not reached).

Conclusions

Results of this phase Ib proof-of-concept study suggest that pembrolizumab has a manageable safety profile and demonstrate evidence of antitumor activity in advanced differentiated thyroid cancer in a minority of patients treated. Further analyses are necessary to confirm these findings.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02054806. Registered 4 February 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy and the eighth most common cancer in the United States [1, 2]. Although the prognosis for most thyroid cancers is generally good (98% overall 5-year survival rate) [2], approximately 10% of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer develop progressive invasive primary disease, 5% develop distant metastases, and 20–30% experience disease recurrence [3].

Metastatic disease is usually treated with a combination of surgery and radioiodine ablation (RAI), and success depends on whether metastasis is in a location amenable to surgical resection or radioiodine uptake in the tumor tissue is significant [1, 4]. Since the identification of multiple kinase inhibitors (MKIs), more treatment options for recurrent/metastatic thyroid cancer are available [5]. Two MKIs—sorafenib [6, 7] and lenvatinib [8, 9]—have been approved in many countries for treatment of advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Results of a phase III randomized trial revealed a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with sorafenib compared with placebo in patients with RAI-refractory, advanced, differentiated thyroid cancer [10]. Additionally, lenvatinib was also associated with significant improvement in PFS and objective response rate (ORR) compared with placebo; median overall survival (OS) was not reached after a median follow-up of 17 months. Lenvatinib was associated with considerable treatment-related toxicity, with a drug-related mortality rate of 2% [11]. Sorafenib and lenvatinib are now recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for the treatment of progressive, RAI-refractory differentiated thyroid carcinoma [4]. However, despite being effective, their duration of response is limited, and disease ultimately progresses. Therefore, new therapies are needed.

The development and approval of immunotherapeutics for cancer, and immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–CTLA-4 and anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) agents in particular, have altered the treatment landscape for many malignancies [12]. They act to re-establish immune surveillance, from which some cancers are able to hide [12, 13]. The clinical benefit observed with immune checkpoint inhibitors varies with both the immunotherapeutic agent and the type of cancer. However, PD-1 blockade appears to be effective for a wide variety of tumor types [12]. Thyroid cancer cells are known to produce cytokines and chemokines that are able to promote tumorigenesis. In aggressive, recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, the frequency of regulatory T cells is increased, and expression of PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) is correlated with greater risk of recurrence and reduced disease-free survival [12]. Targeting of these immune system components may thus prove useful in the treatment of thyroid cancer. The application of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced thyroid cancer has not been well studied to date.

The PD-1 immune checkpoint pathway regulates induction and maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance via engagement between the PD-1 receptor (expressed on monocytes and T, B, and natural killer cells) and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 [14]. Upregulation of this pathway induces suppression of immune response in many tumors, allowing them to escape immune surveillance [15, 16]. Expression of PD-L1 in advanced differentiated thyroid carcinomas, when detected, has been associated with aggressive disease and poor prognosis, making anti–PD-1 therapy a potential treatment option [3, 17, 18].

Pembrolizumab is a fully humanized, selective immunoglobulin G4/κ anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody that exhibits antitumor activity by blocking interaction between PD-1 and its ligands. It has been found to be effective in head and neck cancers [19,20,21]. Pembrolizumab has demonstrated robust antitumor activity and a favorable safety profile in multiple tumor types, and it is currently approved in more than 60 countries for one or more advanced malignancies.

The aim of this study was to assess the safety, tolerability, and antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1–positive, advanced thyroid cancer who were enrolled in the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 trial.

Methods

Study design and patients

Eligibility criteria were age ≥ 18 years; presence of cytologically or histologically confirmed, PD-L1–positive, locally advanced or metastatic follicular or papillary thyroid cancer in which, per the opinion of the treating physician, previous standard therapy was ineffective, did not occur, or was not considered appropriate; measurable disease based on Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1; and adequate organ function. Patients were not required to be radioactive iodine refractory in order to be enrolled in the study. Exclusion criteria were current or past participation in a study of an investigational agent or investigational device ≤4 weeks before the first dose of treatment; prior anticancer monoclonal antibody therapy ≤4 weeks before the first pembrolizumab dose; immunosuppressive therapy or diagnosis of immunodeficiency therapy ≤7 days before the first pembrolizumab dose; chemotherapy, targeted small-molecule therapy, or radiation therapy ≤2 weeks before the first pembrolizumab dose; therapy with any anti–PD-1, anti–PD-L1, or immune checkpoint inhibitor; active autoimmune disease that necessitated systemic treatment in the preceding 2 years; interstitial lung disease; known additional malignancy that was progressing or necessitated treatment; and active brain metastases. The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee of each participating site and were conducted per the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent to participate. This trial was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov, identifier NCT02054806.

Treatment and assessments

Pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg was administered every 2 weeks via 30-min infusion. Treatment continued for 24 months or until confirmed progressive disease, unacceptable adverse events (AEs), or investigator or patient decision to withdraw. Dosing was interrupted because of unacceptable toxicity but could resume after resolution of toxicity to grade 0/1 within 12 weeks of the last infusion. Response was assessed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging every 8 weeks for the first 6 months and every 12 weeks thereafter. Patients who discontinued pembrolizumab after substantiated complete response (CR) after ≥24 weeks of therapy and ≥ 2 treatments after initial CR, or who discontinued after receiving pembrolizumab for ≥24 months for reasons other than progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity could be eligible for up to 1 year of re-treatment after substantiation by radiographic progressive disease. Patients were permitted to continue to treatment after the onset of progressive disease if the patient’s condition was clinically stable in the investigator’s judgment. AEs were graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0, and were monitored throughout the study and for 30 days after treatment discontinuation (90 days for serious AEs). Immune-mediated AEs were also reported and were defined as events with potentially drug-related immunologic causes that were consistent with an immune phenomenon, regardless of whether they were attributable to the study drug or to an immune response.

Tumor PD-L1 status was determined at a central laboratory during the screening period using either an archived formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor sample or a newly obtained biopsy sample. PD-L1 expression was assessed using a prototype immunohistochemistry assay (QualTek Molecular Laboratories, Goleta, California) [22] and the 22C3 antibody (Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey). PD-L1 positivity was defined as membranous staining on ≥1% modified proportion score or interface pattern as described previously [22]. Note that tumor markers and laboratory evaluations specific for thyroid cancer were not required to be captured by investigators because of the signal-finding nature of the study.

Endpoints

Primary endpoints were ORR, defined as the proportion of patients with a best overall response of confirmed CR or partial response (PR) per RECIST v1.1 by investigator review, and safety and tolerability. Secondary endpoints were PFS (time from enrollment to the first documented occurrence of PD per RECIST v1.1 or death from any cause, whichever occurred first), OS (time from enrollment to death from any cause), and duration of response (time from first RECIST v1.1–based response to progressive disease in patients who experience PR or better).

Statistical analyses

The binomial exact method was used for power and sample size calculations. A sample size of 22 evaluable patients in this cohort was calculated to provide 80% power to demonstrate that the best ORR exceeded 10% at an overall one-sided 8% α level if the true best ORR was 35%. The efficacy population was composed of all patients who received ≥1 dose of pembrolizumab and had measurable disease at baseline per RECIST v1.1. The safety population was composed of all patients who received ≥1 dose of pembrolizumab. A truncated sequential probability test was used to evaluate ORR; PFS, OS, and duration of response were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The data cutoff was February 20, 2017.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics and treatment

Fifty-one patients with thyroid cancer were screened; of 36 (71%) with PD-L1–positive tumors, 22 were enrolled (per eligibility criteria) and received ≥1 dose of pembrolizumab. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1; median age was 61 years (range, 23–76 years); 13 (59%) were women; and 12 (55%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0. Relative proportions of patients with papillary and follicular thyroid cancer were approximately 2:1 (papillary, 68%; follicular, 32%). Nine (41%) patients had ≥2 prior lines of therapy for advanced disease; 11 (50%) patients had previously received an MKI. The most frequent prior treatment was RAI (18 patients [82%]), followed by sorafenib (7 [32%]) and pazopanib (3 [14%]). Among the 22 PD-L1–positive patients enrolled in this cohort, 20 (91%) were PD-L1 positive in the tumor only and 2 (9%) were positive in the tumor and the stroma.

Median follow-up was 31 months (range, 7–34 months). At the data cutoff date, 18 patients (82%) had discontinued the study: 10 because of PD, 7 because of patient or physician decision, and 1 was lost to follow-up; 4 remained on study.

Safety

Eighteen patients (82%) experienced treatment-related AEs, most commonly diarrhea (7 [32%]), fatigue (4 [18%]), pruritus (3 [14%]), and rash (3 [14%]); all but 1 were grade 1 or 2 (Table 2). No grade 4 treatment-related AEs or treatment-related deaths or discontinuations occurred. Immune-mediated AEs were reported in 5 patients: pneumonitis (2 patients, 1 each of grades 1 and 2), interstitial lung disease (1 patient, grade 1), colitis (1 patient, grade 3), and hypothyroidism (1 patient, grade 2).

Antitumor activity

Confirmed PR (by investigator review) was observed in 2 patients, for an ORR of 9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1–29%) (Table 3). Time to response for the 2 patients with substantiated PR were 4 and 5 months, respectively, with response durations of 20 and 8 months, respectively (Fig. 1). Both patients had papillary thyroid cancer. Stable disease (SD) was experienced by 13 patients (59%; 95% CI, 36–79%), with a median duration of 7 months yielding a disease control rate (i.e. confirmed PR + SD) of 68%. SD was achieved by 57% (4/7) of patients with follicular histology and 60% (9/15) of patients with papillary histology. The clinical benefit rate (i.e. confirmed PR + SD ≥6 months) was 50% (95% CI, 28–72%). Seven patients had progressive disease as best response (32%; 95% CI, 14–55%). Of these, 3 patients had follicular cancer and 4 patients had papillary thyroid cancer, representing 43 and 27% of the respective histologic subgroups. Reduction in tumor size (sum of the longest diameter) from baseline was observed in 15 (68%) of 22 patients in whom this parameter was evaluable and was generally maintained (Fig. 2).

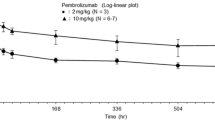

Median PFS was 7 months (95% CI, 2–14 months), and 6- and 12-month PFS rates were 59 and 36%, respectively. Median OS was not reached (95% CI, 22 months to not reached), with 6- and 12-month OS rates of 100 and 90%, respectively (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Until recently, treatment options for advanced differentiated thyroid carcinomas were limited to surgery and RAI [4]. The recent approval of MKIs has improved the therapeutic arsenal, benefiting those whose tumors progress after RAI or for whom surgery is contraindicated. Nonetheless, disease in patients treated with approved agents will inevitably progress. Because thyroid cancer is a relatively common disease with a high unmet medical need in refractory patients, pembrolizumab was evaluated in a thyroid cancer cohort of KEYNOTE-028. In this phase Ib, proof-of-concept study, pembrolizumab was well tolerated in patients with advanced papillary or follicular thyroid cancer that had progressed with standard therapy, and no treatment-related discontinuations or deaths occurred. The safety profile was generally consistent with that observed previously for pembrolizumab [19, 20]. After a median follow-up of 31 months, confirmed ORR was 9%, disease control rate was 68%, and clinical benefit rate was 50%. Two patients had confirmed PR, and, in 13 other patients, median duration of SD was 7 months. Median PFS was 7 months and, although median OS was not reached at the data cutoff date, 6- and 12-month OS rates were high at 100 and 90%, respectively. Although PFS data in this study were greater than those of placebo-treated patients with RAI-refractory, differentiated thyroid cancer whose disease progressed after previous treatment (4–6 months) [10, 11], patients in KEYNOTE-028 were not required to have experienced disease progression with their previous treatment before study entry. These results must also be interpreted considering the biological behavior of advanced thyroid cancer, which is known to often have an indolent course. In addition, patients in KEYNOTE-028 were heavily pretreated; therefore, it is unclear what the PFS for this group would have been without treatment or how the effects of multiple prior therapies may confound these results. Nonetheless, objective responses were observed in a minority of patients treated. Hence, the observed response rates and PFS differences must be substantiated in subsequent clinical trials.

PD-L1 expression has been observed in differentiated thyroid tumors, including the papillary subtype. In one study, 59% (13/22) of differentiated thyroid tumors expressed PD-L1, and 50% of tumors contained PD-1–positive lymphocytes [18]. In another retrospective analysis, membranous PD-L1 expression was observed in 40% (74/185) of all surgically resected papillary thyroid tumors analyzed and in > 70% (53/74) of advanced-stage (III/IV) tumors [3]. In that study, the presence of PD-L1 staining was associated with significantly reduced disease-free survival [3]. The high membranous PD-L1 expression found in advanced-stage tumors suggests that, as in other PD-L1–expressing tumors, pembrolizumab could be an effective therapy for papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. However, archival tissue was permitted in this study and, in some cases, was taken from metastatic sites. In thyroid cancer, this can be a significant limitation because tumor dedifferentiation with progression is a frequent feature [23]. Therefore, the treated lesions may not represent differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Future investigation that requires fresh biopsy specimens taken immediately before therapy, when clinically feasible, may be informative.

Given that KEYNOTE-028 was a signal-finding study, two additional limitations, among others, that might have affected the generalizability of the results were that patients were not required to be iodine refractory before enrollment and that tumor marker and laboratory evaluations were not required to be collected, despite the fact that these items are specific to thyroid cancer. Additional studies that include these items will be needed to further confirm findings.

Conclusion

Results of this proof-of-concept study suggest that pembrolizumab may be effective and have a favorable safety profile in PD-L1–positive thyroid cancer. These data may lay the foundation for further clinical evaluation of pembrolizumab to establish its place in the differentiated thyroid carcinoma therapeutic arena. Clinical benefit of a fixed dose of pembrolizumab (200 mg once every 3 weeks) in advanced differentiated thyroid cancer will be further investigated in the multicohort phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 trial (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02628067).

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CR:

-

Complete response

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- MKI:

-

Multiple kinase inhibitor

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD-1:

-

Programmed death 1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death ligand 1

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- RAI:

-

Radioiodine ablation

- RECIST v1.1:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors, version 1.1

- SD:

-

Stable disease

References

Pacini F, Castagna MG, Brilli L, Pentheroudakis G. Thyroid cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii110–9.

National Cancer Institute: SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Thyroid Cancer. In.; 2016.

Chowdhury S, Veyhl J, Jessa F, Polyakova O, Alenzi A, MacMillan C, Ralhan R, Walfish PG. Programmed death-ligand 1 overexpression is a prognostic marker for aggressive papillary thyroid cancer and its variants. Oncotarget. 2016;7(22):32318–28.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network I: NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology - thyroid carcinoma v1.2016. In. Edited by 1.2016; 2016.

Nguyen QT, Lee EJ, Huang MG, Park YI, Khullar A, Plodkowski RA. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with thyroid cancer. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(1):30–40.

NEXAVAR (sorafenib) tablets, oral. Whippany: Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2014.

Nexavar 200mg film-coated tablets. Berlin: Bayer AG; 2013.

LENVIMA® (lenvatinib) capsules, for oral use. Woodcliff Lake: Eisai, Inc.; 2016.

LENVIMA 4 mg hard capsules LENVIMA 10 mg hard capsules. Hatfield: Esai Europe Limited; 2016.

Brose MS, Nutting CM, Jarzab B, Elisei R, Siena S, Bastholt L, de la Fouchardiere C, Pacini F, Paschke R, Shong YK, et al. Sorafenib in radioactive iodine-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9940):319–28.

Schlumberger M, Tahara M, Wirth LJ, Robinson B, Brose MS, Elisei R, Habra MA, Newbold K, Shah MH, Hoff AO, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):621–30.

Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Fallahi P. Current and future immunotherapies for thyroid cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(2):149–59.

Cavallo F, De GC, Nanni P, Forni G, Lollini PL. 2011: the immune hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(3):319–26.

McDermott DF, Atkins MB. PD-1 as a potential target in cancer therapy. Cancer Medicine. 2013;2(5):662–73.

Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews - Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–64.

Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12293–7.

Cunha LL, Marcello MA, Morari EC, Nonogaki S, Conte FF, Gerhard R, Soares FA, Vassallo J, Ward LS. Differentiated thyroid carcinomas may elude the immune system by B7H1 upregulation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(1):103–10.

Bastman JJ, Serracino HS, Zhu Y, Koenig MR, Mateescu V, Sams SB, Davies KD, Raeburn CD, McIntyre RC Jr, Haugen BR, et al. Tumor-infiltrating T cells and the PD-1 checkpoint pathway in advanced differentiated and anaplastic thyroid Cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(7):2863–73.

Seiwert TY, Burtness B, Mehra R, Weiss J, Berger R, Eder JP, Heath K, McClanahan T, Lunceford J, Gause C, et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):956–65.

Chow LQ, Haddad R, Gupta S, Mahipal A, Mehra R, Tahara M, Berger R, Eder JP, Burtness B, Lee SH, et al. Antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in biomarker-unselected patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 expansion cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(32):3838–45.

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) injection, for intravenous use. Whitehouse Station; 2018.

Dolled-Filhart M, Locke D, Murphy T, Lynch F, Yearley JH, Frisman D, Pierce R, Weiner R, Wu D, Emancipator K. Development of a prototype immunohistochemistry assay to measure programmed death ligand-1 expression in tumor tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(11):1259–66.

Antonelli A, Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Carpi A, Berti P, Materazzi G, Minuto M, Guastalli M, Miccoli P. Dedifferentiated thyroid cancer: a therapeutic challenge. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62(8):559–63.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families and caregivers for participating in the study. The authors would also like to thank Chao Gao (employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA) for contributions to the development of the manuscript. Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was provided by Jacqueline Kolston, PhD, and Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, of the ApotheCom pembrolizumab team (Yardley, PA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc. Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc. Kenilworth, NJ, USA. No grant number is applicable. Representatives of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, and academic advisors designed the study. Authors and sponsor representatives analyzed and interpreted the data. Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Availability of data and materials

Merck & Co., Inc.’s data sharing policy, including restrictions, is available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php. Requests for access to the clinical study data can be submitted through the EngageZone site or via email to dataaccess@merck.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMM acquired data, analyzed data, interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; AV and AP acquired data and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; MSB, RRA, C-CL, SAP-P, and BK acquired data, interpreted the results, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; FdeB interpreted the results, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; KT acquired data and drafted the manuscript; TD acquired data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; JG and PT acquired data, analyzed data, interpreted the results, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; SS analyzed data, interpreted the results, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript; JDC designed the study; analyzed the data; interpreted the results, and critically reviewed or revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee of each participating site (Additional file 1: Table S1) and were conducted per the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JMM: Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, EMD Serono, Genentech. MSB: Research Funding: Merck (institution). AP: Research Funding: Merck (institution). TD: Research Funding: Taiho, Novartis, Merck Serono, Astellas Pharma, Merck, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Pfizer, Lilly Sumitomo Group, Chugai Pharma, Bayer, Kyowa, Hakko Kirin, Daiichi Sankyo, Celgene, Amgen. SAP-P: Research Funding: AbbVie, Inc., Aminex Therapeutics, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Inc., Bristol Myers Squib; Curis, Inc., Five Prime Therapeutics, Genmab, GlaxoSmithKline, Helix BioPharma Corp., Incyte Corp., Medivation, Inc., Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pieris Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pfizer, Puma Biotechnology, Inc., Taiho Oncology, Tesaro, Inc., TransThera Bio, XuanZhu Pharma Co, Ltd., Principia Biopharma, Inc., Cerulean Pharma, Inc., Medimmune, LLC, Boehringer Ingelheim, Jacobio Pharmaceuticals Co, Ltd. SS: Employment: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc. PT: Employment (at the time of analysis): Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc.; Current employment: Regeneron; Stockholder: MannKind Corporation and Regeneron. JC: Employment: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck and Co., Inc. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee of Each Participating Site. Description of data: Provides details of institutional review board/ethics committees for each participating site. (PDF 118 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehnert, J.M., Varga, A., Brose, M. et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in patients with advanced, PD-L1–positive papillary or follicular thyroid cancer. BMC Cancer 19, 196 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5380-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5380-3