Abstract

Background

Many studies have reported the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and its effects and prognosis in patients with lung cancer, but few have considered quality of life and survival of patients with lung cancer according to severity of airway obstruction. This study investigated the presence of COPD and the severity of airway obstruction in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and analyzed how these factors affected symptoms, quality of life, and prognosis.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the prospective lung cancer database of the Catholic Medical Centers at the Catholic University of Korea from 2014 to 2017. We enrolled patients with advanced NSCLC and evaluated quality of life using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30. We also estimated pulmonary function and analyzed survival data.

Results

Of the 337 patients with advanced NSCLC, 170 (50.5%) had COPD and 167 (49.5%) did not. Significant differences were observed in symptoms between the two groups. The COPD group complained of more symptoms, such as cough, sputum, and dyspnea, than those in the non-COPD group. The distribution according to the severity of obstruction in the COPD group was as follows: Grade 1 (FEV1 ≥ 80%) 35 patients (20.6%), Grade 2 (50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%) 103 patients (60.6%), Grade 3 (30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%) 24 patients (14.1%), and Grade 4 (FEV1 < 30%) 8 patients (4.7%). The presence of COPD did not affect overall quality of life in patients with NSCLC, but as the airway obstruction increased, physical function decreased, and fatigue and dyspnea were more frequent. The overall median survival of the COPD group was shorter than that of the non-COPD group (median survival, 224 vs. 339 days, p = 0.035).

Conclusions

In this study, a high prevalence of COPD was found among patients with advanced NSCLC, and COPD patients complained about various symptoms and had diminished quality of life in several sectors. Therefore, it is necessary to actively evaluate quality of life, lung function, and symptoms in patients with lung cancer and reflect them in the treatment and management plans of these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is a disease with high incidence and mortality rates worldwide. The American Cancer Society estimated that in the United States, 162,510 people died of lung cancer in 2016 [1]. In Europe, the socioeconomic costs due to lung cancer amounted to 18.8 billion Euros in 2009, which is about 15% of the total cost of cancer in the region [2]. Thus, lung cancer is considered to be one of the most economically burdensome diseases at the national level. At the individual level, lung cancer often causes not only general symptoms, such as pain and fatigue but also various respiratory symptoms, including cough, sputum, and dyspnea. Additionally, as lung cancer patients primarily have extensive-stage disease at the time of diagnosis, they tend to have significant mental difficulties, such as fear of death, depression, and anxiety [3].

The main cause of lung cancer is smoking [4], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is typically caused by smoking. Therefore, COPD and lung cancer have a close relationship in terms of prevalence and symptoms reported by patients. COPD is an independent risk factor for lung cancer, and smokers with an obstruction have more than five times the incidence of lung cancer than those with normal lung function [5]. Cough, sputum, and dyspnea are the most common respiratory symptoms experienced by patients with COPD, and these symptoms can reduce quality of life. Similarly, various symptoms, including dyspnea and quality of life, affect the prognosis of patients with lung cancer. In particular, respiratory symptoms and changes in pulmonary function, which serve as diagnostic criteria for COPD, have a very negative impact on the prognosis of patients with lung cancer [6,7,8]. Many studies have reported the prevalence of COPD and its effects and prognosis in patients with lung cancer, but few have considered quality of life and survival of patients with lung cancer according to severity of airway obstruction. Therefore, this study examined the presence of COPD in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), investigated differences in quality of life and symptoms according to severity of airway obstruction, and analyzed how these factors affect prognosis.

Methods

Study population and data collection

A retrospective study of patients enrolled in the Catholic Medical Centers (CMC) lung cancer registry run by Catholic University (CMC lung cancer registry) was conducted from October 2014. The CMC lung cancer registry was developed to investigate the relationship between initial clinical parameters and outcomes through the serial observation in patients with lung cancer. The initial symptoms and quality of life through questionnaire survey, clinical characteristics, smoking history, comorbidities, pulmonary function tests, histological and cytological diagnosis, staging and treatment outcomes were collected prospectively and systematically from the time of diagnosis to death. Among the patients who were histologically and cytologically diagnosed with NSCLC, 337 with stage-3 and stage-4 NSCLC were selected for the study based on the Seventh Edition of the American Thoracic Society Tumor Node Metastasis classification [9,10,11,12]. Quality of life was evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-C30 (Korean version) [13,14,15]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 was found to be a reliable and valid measure of reported health-related quality of life [16]. The validity and reliability of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (Korean version) has been reported in previous study (Cronbach’s α > 0.7) [17]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is composed of multi-item and single scales: five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea & vomiting and pain), six single items (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and difficulties) and a global health status/QOL scale [15]. All scales and items are linearly transformed to 0–100 scale [18]. For the 5 functional scales and the global quality of life scale, a higher score represents a better level of functioning. For the symptom scales and items, a high score corresponds to a higher level of symptom [18]. The diagnosis of COPD was made when the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) was < 70% based on the 2014 GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) guidelines. The distribution of patients with COPD according to severity of the obstruction was classified into Grade 1 (FEV1 ≥ 80%), Grade 2 (50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%), Grade 3 (30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%), and Grade 4 (FEV1 < 30%) [19, 20]. Data regarding patients’ age, sex, smoking history, histological type and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG PS) were also obtained from the registry. The ECOG PS is widely used to assess the functioning of cancer patients specifically for the purposes of oncological decision making, as well as prediction of patients’ prognosis. It provides a five-point scale which incorporates elements such as ambulatory status and need for care [21]. A survival analysis was conducted based on the last date of tracking observations (June 30, 2017). This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Catholic Medical Center (XC140IMI0070).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patients’ demographic characteristics, symptoms and QLQ score. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using the Pearson’s chi-square test or unpaired t-test for patient’s characteristics and QLQ scores between the COPD group and non COPD group, the Kruskal-Wallis test for QLQ scores between FEV1 groups. Additionally, Cochran –Mantel -Haenszel statistics were used to test for associations, and generalized linear models were used to test for a linear trend. Survival curves according to COPD and non- COPD were drawn using the Kaplan- Meier Method, and compared by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with the Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors. The factors significantly associated with patient survival in univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were included in multivariate analysis. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) or R (version 3.4.1; R Computing, Vienna, Austria). A p -value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 337 patients were enrolled in this study and were classified into two groups according to the presence of COPD. The general and clinical characteristics of the subjects are as follows (Table 1). Among the subjects, the number of patients with COPD (FEV1/FVC < 70) was 170 (50.5%), and the number without (FEV1/FVC ≥ 70) was 167 (49.5%). The average age of the COPD group was 70.4 years, and that of the non-COPD group was 63.2; the distribution of patients aged >65 years was significantly higher in the COPD group than that in the non-COPD group. A total of 154 males (90.6%) were in the COPD group, and 108 (64.7%) were in the non-COPD group, indicating significantly larger number compared to that of females. The distribution of smokers was significantly higher in the COPD group [152 (89.4%)], and [104 (62.3%)] than that in the non-COPD group. The histology results were significant: the COPD group had a higher proportion of squamous-cell carcinoma, whereas the proportion of adenocarcinoma was higher in the non-COPD group. In terms of comorbid conditions, the number of patients with one or more comorbidities was 103 (60.6%) in the COPD group, and 75 (44.9%) in the non-COPD group. In particular, the COPD group had higher proportions of tuberculosis [COPD vs. non-COPD; 38 (22.4%) vs. 16 (9.6%)], and hypertension [COPD vs. non-COPD; 48 (28.2%) vs. 30 (18.0%)]. The proportions of old age, smoking history, comorbidities, and squamous cell type were significantly higher in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group. The distribution of patients with COPD according to severity of the airway obstruction was Grade 1 (FEV1 ≥ 80%) 35 patients (20.6%); Grade 2 (50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%) 103 patients (60.6%); Grade 3 (30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%) 24 patients (14.1%); and Grade 4 (FEV1 < 30%) 8 patients (4.7%).

Symptoms of patients between the groups with and without COPD

Table 2 lists the differences in symptoms between COPD and non-COPD patients. Cough was observed in 117 patients with COPD (68.8%) and 95 patients with non-COPD (56.9%); sputum in 99 patients with COPD (58.2%) and 74 patients with non-COPD (44.3%); dyspnea in 60 patients with COPD (35.3%) and 33 patients with non-COPD (19.8%). As shown in Table 2, cough, sputum, and dyspnea were more common in patients with COPD than those without. Additionally, the number of symptoms was significantly greater in patients with COPD than in those without at the time of the lung cancer diagnosis(p < .0001).

EORTC-QLQ scores between the groups with and without COPD

The EORTC QLQ-C30 scale was analyzed according to the presence of COPD in patients with advanced NSCLC (Table 3). Overall quality of life tended to be lower in patients with COPD than in patients without (p > 0.05). However, cognitive and social function scales were significantly lower in the COPD group, and the severity of dyspnea and appetite loss was significantly higher on the symptom scale.

EORTC-QLQ scores of patients with COPD according to airway obstruction

Table 4 lists the EORTC QLQ-C30 results according to severity of airway obstruction in the COPD group among patients with advanced NSCLC. The overall quality of life in patients with COPD was significantly lower as the severity of obstruction increased. In particular, a significant difference in the decline of physical functioning was observed between the groups. The severity of fatigue and dyspnea increased significantly with severity of airway obstruction.

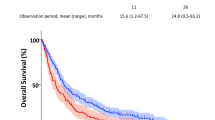

Effects of COPD on survival in NSCLC

The results of the analysis of whether the presence of COPD affected survival of patients with advanced NSCLC are as follows (Fig. 1). The overall median survival time for all patients was 111 days. The overall median survival of the COPD group was shorter than that of the non-COPD group (median survival, 224 vs. 339 days, p = 0.035). A univariate analysis indicated that the presence of COPD and stage, sex, and FEV1 level had significant effects on patient survival. However, the multivariate analysis revealed that advanced stage (HR, 1.87; 95% CI: 1.26–2.77) and male sex (HR, 2.32; 95% CI: 1.45–3.72) were significant poor prognostic factors affecting survival in patients with NSCLC (Table 5).

Discussion

Smoking is the major cause of lung cancer and is also known to cause various other diseases, including diabetes and cerebral cardiovascular diseases. In particular, smoking is closely related to COPD. This study investigated quality of life and symptoms of COPD and analyzed how COPD affected prognosis in patients with advanced NSCLC. The results confirmed that patients with advanced NSCLC and COPD had more symptoms and reduced quality of life in several aspects, but these did not affect the survival rate in the patients. In this study, the prevalence of COPD was 50.5% among all patients with advanced NSCLC. Several studies have focused on the frequency of COPD in lung cancer: Ytterstad et al. reported that 39% of patients with lung cancer have COPD [22]. In the present study, the prevalence rate of COPD in patients with NSCLC was relatively higher than that previous study, possibly because it excluded patients with early lung cancer who have a shorter smoking history and comparatively good lung function. A comparison of the clinical characteristics between the COPD and non-COPD groups revealed that more patients in the COPD group were advanced in age, had a smoking history, and were diagnosed with squamous cell type, which is consistent with results of previous studies [23, 24]. A large number of comorbidities also occurred in the COPD group. Therefore, it can be inferred that patients with NSCLC and COPD had more respiratory symptoms and worse prognosis. Respiratory symptoms such as cough, sputum, and dyspnea were more frequent in patients with NSCLC and COPD than in those without, which supports the hypothesis and is consistent with the results of previous studies [25]. Declines in lung function and the severity of symptoms in patients with lung cancer are known to have significant effects on quality of life [26], and in particular, patients who suffer from dyspnea are known to be at higher risk of death and poor prognosis than those without dyspnea [6, 8]. Therefore, in this study, the quality of life in patients with advanced NSCLC was analyzed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 scale. No significant difference was found in the overall quality of life between the COPD and non-COPD groups. However, the COPD group had significantly reduced quality of life in certain aspects, such as the functional scale, cognitive and social functions, and some symptom scales, and the subgroup analysis results confirmed that overall quality of life decreased in the COPD group as the severity of airway obstruction increased. In particular, the difference was remarkable on the symptom scale related to dyspnea as well as the degree of decrease in social functioning. These results indicated that the severity of symptoms, including dyspnea, can affect various aspects of quality of life among patients with advanced NSCLC. Therefore, it is useful not only to collect baseline data regarding patient cancer status, but also to accurately evaluate patient symptoms, functional factors, presence of COPD, and severity of airway obstruction to present treatment directions for patient with lung cancer. Counselling for smoking cessation, prescription inhalers, pulmonary rehabilitation and other tailored management can improve functional status and relieve symptom burden of individual patients. Special attention by medical personnel is required.

This study also analyzed how COPD affected survival rates among patients with advanced NSCLC. Survival time was significantly shorter in the COPD group than that in the non-COPD group, which was a significant result in the univariate analysis, but not in the multivariate analysis corrected for the effects of other variables. This finding is similar to that of a previous study, which reported that the presence of COPD has no significant effect on prognosis for lung cancer patients [27]. This result suggests that it is difficult to determine the prognosis for patients with advanced NSCLC and COPD based on this single variable, because patients with COPD are more likely to have advanced stage, poor performance, and various complications during the treatment process.

This study had the following limitations. First, it was difficult to generalize the results because of the small sample size. However, the subjects were limited to patients with stage-3 and stage-4 NSCLC; those with stage-1, or stage-2 NSCLC were excluded, which had the effect of excluding other factors, such as curative surgery, that affects survival of patients. Therefore the subjects became homogeneous, which was an advantage, and the findings are highly relevant because they reveal how COPD affects symptoms, quality of life, and prognosis, even in patients with advanced lung cancer, unlike previous studies of long-term survivors after surgery [6]. Second, because the study had a retrospective design, its statistical power is rather weak. However, the questionnaire survey regarding symptoms and quality of life was done at the time of diagnosis, and objective lung functions were faithfully reflected, so the findings of this study are considered to be highly valuable for research. Third, the symptom questionnaire, pulmonary function from enrolled patients were recorded prospectively at the time of lung cancer diagnosis. Therefore, it was difficult to clearly identify the order of two diseases. However, COPD and lung cancer have a common etiology of smoking. And there are many opinions that COPD could be a driving factor in lung cancer by chronic systemic inflammation and DNA damage in time sequence [28]. We can suggest that patients with lung cancer and COPD at baseline develop more symptoms and lower quality of life than without COPD.

Conclusions

In this study, patients with advanced NSCLC had a high prevalence rate of COPD, and patients with COPD had more symptoms, such as cough, sputum, and dyspnea, than those without COPD. Quality of life was confirmed to decrease in several aspects in patients with COPD, and overall quality of life decreased as the severity of airway obstruction increased in this group. However, no significant differences in prognosis were observed according to the presence of COPD in patients with advanced NSCLC. Based on these results, an active assessment needs to be conducted to evaluate the quality of life and symptoms in patients with lung cancer and investigate the severity of airway obstruction through pulmonary function testing at the time of the initial diagnosis. Furthermore, multilateral efforts are needed to improve the quality of life for patients with lung cancer.

Abbreviations

- AP:

-

Appetite loss

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CF:

-

Cognitive functioning

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CO:

-

Constipation

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DI:

-

Diarrhea

- DY:

-

Dyspnea

- EF:

-

Emotional functioning

- EORTC-QLQ:

-

European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire

- FA:

-

Fatigue

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FI:

-

Financial difficulties

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- NV:

-

Nausea and vomiting

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PA:

-

Pain

- PF:

-

Physical functioning

- QL:

-

Global health status

- RF:

-

Role functioning

- SF:

-

Social functioning

- SL:

-

Insomnia

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30.

Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A, Sullivan R. Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: a population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(12):1165–74.

Braun DP, Gupta D, Staren ED. Quality of life assessment as a predictor of survival in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:353.

Bae J, Gwack J, Park SK, Shin HR, Chang SH, Yoo KY. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, tuberculosis and risk of lung cancer: the Korean multi-center cancer cohort study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007;40(4):321–8.

Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl):2565–76.

Yun YH, Kim YA, Sim JA, Shin AS, Chang YJ, Lee J, et al. Prognostic value of quality of life score in disease-free survivors of surgically-treated lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:505.

Grutters JP, Joore MA, Wiegman EM, Langendijk JA, de Ruysscher D, Hochstenbag M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients surviving non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 2010;65(10):903–7.

Ban WH, Lee JM, Ha JH, Yeo CD, Kang HH, Rhee CK, et al. Dyspnea as a prognostic factor in patients with non-small cell lung Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57(5):1063–9.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(2):244–85.

Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Tanoue LT. The new lung cancer staging system. Chest. 2009;136(1):260–71.

Mountain CF, Dresler CM. Regional lymph node classification for lung cancer staging. Chest. 1997;111(6):1718–23.

Mountain CF. Revisions in the international system for staging lung Cancer. Chest. 1997;111(6):1710–7.

Osoba D, Zee B, Pater J, Warr D, Kaizer L, Latreille J. Psychometric properties and responsiveness of the EORTC quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) in patients with breast, ovarian and lung cancer. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):353–64.

Ringdal G, Ringdal K. Testing the EORTC quality of life questionnaire on cancer patients with heterogeneous diagnoses. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(2):129–40.

Kaasa S, Bjordal K, Aaronson N, Moum T, Wist E, Hagen S, et al. The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30): validity and reliability when analysed with patients treated with palliative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31(13–14):2260–3.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76.

Yun YH, Park YS, Lee ES, Bang S-M, Heo D, Park S, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(4):863–8.

Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Grønvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 2001.

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Rodriguez-Roisin R. The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (GOLD)–why and what? Clin Respir J. 2012;6(4):208–14.

Fabbri LM, Hurd S. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD: 2003 update. Eur Respiratory Soc. 2003.

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M. Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32(7):1135–41.

Ytterstad E, Moe PC, Hjalmarsen A. COPD in primary lung cancer patients: prevalence and mortality. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:625–36.

Lee SJ, Lee J, Park YS, Lee CH, Lee SM, Yim JJ, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the mortality of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(6):812–7.

Qiang G, Liang C, Xiao F, Yu Q, Wen H, Song Z, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on postoperative recurrence in patients with resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:43–9.

Wasswa-Kintu S, Gan WQ, Man SF, Pare PD, Sin DD. Relationship between reduced forced expiratory volume in one second and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2005;60(7):570–5.

Mohan A, Singh P, Singh S, Goyal A, Pathak A, Mohan C, et al. Quality of life in lung cancer patients: impact of baseline clinical profile and respiratory status. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16(3):268–76.

Izquierdo JL, Resano P, El Hachem A, Graziani D, Almonacid C, Sánchez IM. Impact of COPD in patients with lung cancer and advanced disease treated with chemotherapy and/or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1053–8.

Durham AL, Adcock IM. The relationship between COPD and lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(2):121–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CCNI (Facility of the clinical research, Seoul, Korea) for data analysis, especially Sug Kyung Kim and Hyun Kyung Park.

Funding

This study was not supported by any grant.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed during the present study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: YSY, KYS. Acquisition of data: YSY. Analysis and interpretation of data: YSY, WHB. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: YSY, WHB. Study supervision: KYS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Catholic Medical Center, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

The authors consent to the publication of the manuscript and all materials attached.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, YS., Ban, W. & Sohng, KY. Effect of COPD on symptoms, quality of life and prognosis in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 18, 1053 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4976-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4976-3