Abstract

Background

This systematic review was conducted to explain the association between dairy products and colorectal cancer (CRC) risk in Middle Eastern and North African countries (MENA).

Methods

The database consulted were PubMed, Clinical Trials, and Cochrane to extract the relevant studies published till the 31stof December 2016, using inclusion and exclusion criteria according to Prisma Protocol. The characteristics of these studies comprised the consumption of all types of dairy products in relation to CRC risk.

Results

Seven studies were included in this review. For dairy products overall, no significant association was found. Regarding modern dairy products, included studies found controversial results with OR = 9.88 (95% CI: 3.80–24.65) and ORa = 0.14 (95% CI: 0.02–0.71). A positive association was reported between traditional dairy products and CRC risk, to OR = 18.66 (95% CI: 3.06–113.86) to OR = 24 (95% CI: 1.74–330.82) to ORa = 1.42 (95% CI: 0.62–3.25), ptrend = 0.03. Calcium was inversely associated with the CRC risk with ORa = 0.08 (95% CI: 0.04–0.17).

Conclusion

This is the first systematic review which illustrated the association between dairy consumption and CRC risk in MENA region. The results were inconsistent and not always homogeneous. Further specified studies may be warranted to address the questions about the association between CRC and dairy products in a specific context of MENA region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide [1], with nearly 1.4 million new cases diagnosed in 2012 and 694.000 deaths [2]. There is a large geographical variation of CRC incidence, that is very high in developed countries compared with developing countries [3], but there is an increasing incidence in countries undergoing nutritional transitions [4, 5].

Several studies have provided solid evidence that lifestyle and dietary factors are likely to be the major determinants of CRC risk [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Milk and dairy products have the distinction of being composed of different elements; some of which could hypothetically increase the risk of certain diseases [13]; while others may decrease it [14]. In fact, the evidence that milk and calcium protect against CRC was judged as probable by an international panel of experts [12, 15, 16]. Most of these results come from North-American and European countries. Little is known about this relationship in MENA countries.

MENA countries have several common factors such as environment, culture, and some dietary habits. Furthermore, this region is incurring nutrition transition, which is associated with an increased burden of non-communicable diseases [17,18,19]. This nutrition transition is characterized by the increasing consumption of some westernized foods including dairy products [20].

There are two types of dairy products in this region: modern products which are similar to European countries as (total, semi-skimmed, and skimmed) milk, (hard, semi-hard, soft and fresh) cheese, and (double, fresh and ice) cream, and traditional products which differ by their composition. The main traditional dairy products of North African countries as well as in Middle East countries are Lben, Raib, Jben, Klila, zebda beldia, Zabadi, Karish cheese, Aoules, Tallaga cheese, Mish cheese, Domiati cheese, Rigouta, Kishk, Laban, Labaneh, Shenineh, Shenglish, Keshkeh, Akawieh, kefir and Chelal [21, 22]. All these traditional dairy products are prepared by simply allowing the raw milk to ferment spontaneously at room temperature (15° to 25 °C) for 1 to 3 days depending on the season [23]. The presence of mycotoxins, the lack of veterinary care, and the poor sanitary conditions are the biggest problems challenging public health safety of these products [21].

The consumption of dairy products in MENA region has increased during the last two decades from 30 to 150 kg/capita/year [24]. However, this increase is small when compared with the main producing countries such as India, the United States of America, China, Pakistan and Brazil [25].

The increasing incidence of CRC in this region could be related to this nutrition transition and also to the nutritional specificities of this region, including traditional dairy products which may affect the genetic mutation profile.

The present systematic review aimed at describing the associations between dairy products and CRC risk in MENA countries, based on the published scientific literature.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted an exhaustive search for full text articles in databases, namely in: Pub Med ( http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih .gov ), Cochrane ( www.thecochranelibrary.com ), and in Clinical Trials ( clinicaltrials .gov ). We used the key words “dairy products” (any type of Milk, whole milk, skimmed milk, semi skimmed milk, milk free fat, soya milk), Cheese (hard, soft, fresh, semi hard), Yogurt, Cream (ice cream, fresh cream, double cream), “traditional dairy products” (Lben, Raib, Jben, Klila, zebda beldia, Zabadi, Karish cheese, Aoules, Tallaga cheese, Mish cheese, Domiati cheese, Rigouta, Kishk, Labaneh, Shenineh, Shenglish, Keshkeh, Akawieh, and Chelal); and “Colorectal cancer, Colon cancer, and Rectal cancer”. We have also selected the areas of “North African countries” (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia) and “Middle east countries” (Turkey, Bahrain, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen). All identified studies published until the 31st December 2016 were considered.

Inclusion criteria

The studies that were included in this review were original studies conducted among people living in the MENA region. The surveys investigated the associations between dairy products and CRC, and provided estimates of the associations, by reporting the odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) for analytical studies or means comparison and differences in the percentage for clinical trials with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or p-value. All reviewed articles were published in English or French. Ecological [26, 27], laboratory and animal [28,29,30,31] studies, and off topic studies [32,33,34,35] were excluded (Table 1). The bibliographic research took place over a period of two months.

Extraction data

We extracted the following data in each paper intended for reviewing: the name of the first author, the country as well as the design of study, the number of participants and the year of publication, the exposure and confounding factors, the specific characteristics and the outcomes, the main findings and the effects.

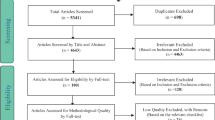

17 Relevant publications were selected first upon reading their titles and abstracts, and by reading the full texts of the chosen articles. Upon excluding ten studies which did not meet the criteria (for the most part laboratory and animal studies), only seven studies were singled out for reviewing (Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using PRISMA guidelines [36], and they were evaluated by the following lines: the accuracy as well as the validity of the questions (answers per evidence), and the representability of the studied population. The synthesis (Table 2) reflected the strength of the findings in relation to the types of the study design [37] (level), and their methodological weaknesses (the biases and limitations of each study).

Results

Seven studies were included in this review, representing five countries: Egypt, Jordan (Arafa et al., Suhad et al., and Tayyem et al.,), Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia. The study results were summarized in Table 3.

Concerning the relation between overall dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese, and Labaneh) and CRC risk, the Jordanian studies (Arafa et al., and Suhad et al.,) [38, 39] did not find any significant association.

Regarding modern dairy products, the Tunisian and the Saudi Arabian studies [40, 41] found controversial results. The Saudi Arabian study found an increased risk of CRC related to milk OR = 9.88 (95% CI: 3.80–24.65), while the Tunisian study found a decreased risk of CRC related to milk OR = 0.14 (95% CI: 0.02–0.71). Concerning cheese consumption, the Saudi Arabian study [41] found it a risk factor OR = 8 (95% CI: 1.40–45.75) only for men.

As for traditional dairy products and CRC risk, the Saudi Arabian and the Jordanian studies [41, 42] demonstrated that traditional dairy products were a risk factor. For a Jordanian study (Tayyem et al.,) [42], the consumption of labaneh was found to be associated with the risk of CRC (OR = 1.42, Ptrend = 0.038), likewise the Saudi Arabian study [41] showed that the consumption of laban, and labaneh, 4 times or above a week resulted in an increase in the CRC risk respectively Laban OR = 18.66 (95% CI: 3.06–113.86) and Labnah OR = 24 (95% CI: 1.74–330.82).

For the relationship between calcium and CRC risk, the Egyptian [43] and Israelian [44] studies found that calcium is a protective factor. For the Egyptian study, calcium rich diet was considered as a protective factor with OR = 0.08 (95% CI: 0.04–0.17). The Israelian clinical trial concluded that long-term calcium supplements and long-term dietary habits significantly suppressed rectal epithelial proliferation (REP) in adenoma patients.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed at describing the relationship between dairy products and CRC in MENA countries. Some of these included studies reported that dairy products were a protective factor for CRC; others considered them as a risk factor.

Three studies in total found that dairy products were protective factors, representing three countries in this region: Egypt, Tunisia, and Israel. Several studies found similar results and showed that milk was considered as a protective factor because of its high calcium concentration [45,46,47,48,49]. In fact, the high intake of calcium was associated with a decreased risk for CRC [50] and calcium supplements were used to prevent CRC [51]. Moreover, milk constituents other than calcium may also contribute to the anti-neoplastic activity, including conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) which has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immune modulatory properties [52,53,54].

Saudi Arabian, and Jordanian studies [41, 42] found that dairy products including traditional ones were considered as risk factors. This result was similar to a longitudinal study which concluded that highly childhood dairy intake increased CRC risk [55]. For traditional dairy products, despite the acidic nature of these products (pH 5.0–5.5) [22] they showed a high number of indicator microorganisms [56]. This can be explained by the poor hygienic conditions in which these products were prepared, as well as the poor bacteriological quality of the raw milk used for their manufacture [22]. Furthermore, these traditional products are high in fat content [57]. Several studies showed that a high fat consumption increased the concentration of bile acid which can promote CRC [58,59,60].

In the same country Jordan, two case-control studies (Arafa et al., and Suhad et al.,) [38, 39] did not find any relationship between dairy products and the risk of CRC development. Some cohort studies showed the same results but only for total milk [61].

The results of the examined surveys are not only inconsistent and controversial, they have in addition several limitations: Some studies were conducted based on a small sample size and the controls were recruited among inpatients [40, 41] who have other diseases than cancer and have been following a diet because of them. Thus, these samples may not be representative of the targeted population.

Regarding the Egyptian study [43], it included already treated cases of CRC, which may affect the quality of the collected data in the way that patients probably, changed their diet after being diagnosed. Indeed, the study did not exclude cases and controls that followed a diet.

Moreover, dietary history was evaluated in most of these studies, by the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and during 2 years earlier to cancer as it is the case for the Egyptian study. In most cases, these FFQs were not validated and the frequency of each food consumption was calculated by a scale of two values: Rare /frequent. Thus, the quality of usable questionnaire was weak which might have led to a lack of information and precision, and might have over- or under-estimated dietary intake.

Equally important, data analysis was not always adjusted for all potential confounders as energy intake, BMI, nutrient intake, and alcohol intake. Therefore, results from these studies ought to be interpreted with caution.

The major limit of the Israelian study [44], even if it’s a prospective study, was the low number of voluntary participants, alongside with the large proportion of intervened patients who did not finish the 1 year of calcium intervention and non-intervened patients who did not comply with the 1 year rectal biopsy. This study may lack of power and its results may not apply in a similar situation.

Conclusion

This review, which is the first study in its kind in MENA countries, presented the main results about the association between CRC and dairy products in this region. The highlighted results were inconsistent, controversial, and studies had several limitations. Further studies with a best quality of methodology, are needed to address the questions about the association between CRC and dairy products in a specific context of MENA region.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

Confidence Intervals

- CLA:

-

Conjugated Linoleic Acid

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- MENA:

-

Middle Eastern and North African countries

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- REP:

-

Rectal Epithelial Proliferation

- RR:

-

Relative Risk

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. A Cancer Journal of Clinicians. 2012;65(2):87–108.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):359–86.

International Agency for Research on Cancer: World Cancer Report; 2014.

Belahsen R. Nutrition transition and food sustainability. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73(3):385–8.

Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, Dicker DJ, Chimed-Orchir O, Dandona R, et al. Global, regional, and National Cancer Incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncology. 2016;3(4):524–48.

Haenszel W, Kurihara M. Studies of Japanese migrants. I. Mortality from cancer and other diseases among Japanese in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968;40(1):43–68.

Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2137–50.

McMichael AJ, McCall MG, Hartshorne JM, Woodings TL. Patterns of gastro-intestinal cancer in European migrants to Australia: the role of dietary change. Int J Cancer. 1980;25(4):431–7.

Baena R, Salinas P. Diet and colorectal cancer. Maturitas. 2015;80(3):258–64.

Chen Z, Wang PP, Woodrow J, Zhu Y, Roebothan B, Mclaughlin JR, Parfrey PS. Dietary patterns and colorectal cancer: results from a Canadian population-based study. Nutr J. 2015;14(8)

Moskal A, Freisling H, Byrnes G, Assi N, Fahey MT, Jenab M, Ferrari P, Tjønneland A, Petersen KE, Dahm CC, et al. Main nutrient patterns and colorectal cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition study. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(11):1430–40.

Song M, Garrett WS, Chan AT. Nutrients, foods, and colorectal cancer prevention. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1244–60.

Qu B, Zhan H, Hao Q. Role of circulating and supplemental calcium and vitamin D in the occurrence and development of colorectal adenoma or colorectal cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;

Um CY, Fedirko V, Flanders WD, Judd SE, Bostick RM. Associations of calcium and milk product intakes with incident, sporadic colorectal adenomas. Nutr Cancer. 2017;69(3):416–27.

World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007.

Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T. Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk:a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(1):37–45.

Aljefree N, Ahmed F. Association between dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease among adults in the Middle East and North Africa region: a systematic review. Food and Nutrition Research. 2015;59

Fahed AC, El-Hage-Sleiman AK, Farhat TI, Nemer GM. Diet, genetics, and disease: a focus on the Middle East and North Africa region. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2012;2012(2012):19.

Fahed AC, El-Hage-Sleiman AK, Farhat TI, Nemer GM. Diet, genetics, and disease: a focus on the middle east and north Africa region. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2012;2012

Golzarand M, Mirmiran P, Jessri M, Toolabi K, Mojarrad M, Azizi F. Dietary trends in the Middle East and North Africa: an ecological study (1961 to 2007). Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(10):1835–44.

Benkerroum N. Traditional fermented foods of north African countries: technology and food safety challenges with regard to microbiological risks. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2013;12(1):54–89.

Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations: The technology of traditional milk products in developing countries. 1990.

National Research Council (US) Panel on the Applications of Biotechnology to Traditional Fermented Foods: Applications of Biotechnology to Fermented Foods: Report of an Ad Hoc Panel of the Board on Science and Technology for International Development.: National Academy Press. Washington, D.C; 1992.

OECD/FAO: “Dairy and Dairy Products”, in OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016-2025. Publishing, Paris 2016.

M’hamed MERDJI, Marion Kussmann GACIC, Selma Tozanli: The dairy products market -Documentary study- LACTIMED 2015.

Abbastabar H, Roustazadeh A, Alizadeh A, Hamidifard P, Valipour M, Valipour AA. Relationships of colorectal cancer with dietary factors and public health indicators: an ecological study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(9):3991–5.

Rohani-Rasaf M, Abdollahi M, Jazayeri S, Kalantari N, Asadi-Lari M. Correlation of cancer incidence with diet, smoking and socio- economic position across 22 districts of Tehran in 2008. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(3):1669–76.

Attaallah W, Yilmaz AM, Erdoğan N, Yalçin AS, Aktan AO. Whey protein versus whey protein hydrolyzate for the protection of azoxymethane and dextran sodium sulfate induced colonic tumors in rats. Pathology Oncology Research. 2012;18(4):817–22.

Cenesiz S, Devrim AK, Kamber U, Sozmen M. The effect of kefir on glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA) and nitric oxide (NO) levels in mice with colonic abnormal crypt formation (ACF) induced by azoxymethane (AOM). Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2008;115(1):15–9.

Habib HM, Ibrahim WH, Schneider-Stock R, Hassan HM. Camel milk lactoferrin reduces the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and exerts antioxidant and DNA damage inhibitory activities. Food Chem. 2013;141(1):148–52.

Khoury N, El-Hayek S, Tarras O, El-Sabban M, El-Sibai M, Rizk S. Kefir exhibits anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on colon adenocarcinoma cells with no significant effects on cell migration and invasion. Int J Oncol. 2014;45(5):2117–27.

Almurshed KS. Colorectal cancer: case-control study of sociodemographic, lifestyle and anthropometric parameters in Riyadh. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(4):817–26.

Bener A, Moore MA, Ali R, El Ayoubi HR. Impacts of family history and lifestyle habits on colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study in Qatar. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(4):963–8.

Can G, Topuz E, Derin D, Durna Z, Aydiner A. Effect of kefir on the quality of life of patients being treated for colorectal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(6):335–42.

Topuz E, Derin D, Can G, Kürklü E, Cinar S, Aykan F, Cevikbaş A, Dişçi R, Durna Z, Sakar B, et al. Effect of oral administration of kefir on serum proinflammatory cytokines on 5-FU induced oral mucositis in patients with colorectal cancer. Investig New Drugs. 2008;26(6):567–72.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest. 1989;95:2S–4S.

Arafa MA, Waly MI, Jriesat S, Al Khafajei A, Sallam S. Dietary and lifestyle characteristics of colorectal cancer in Jordan: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(8):1931–6.

Abu Mweis SS, Tayyem RF, Shehadah I, Bawadi HA, Agraib LM, Bani-Hani KE, Al-Jaberi T, Al-Nusairr M. Food groups and the risk of colorectal cancer: results from a Jordanian case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(4):313–20.

Guesmi F, Zoghlami A, Sghaiier D, Nouira R, Dziri C. Alimentary factors predisposing to colorectal cancer risk: a prospective epidemiologic study. LaTunisie Médicale. 2010;88(3):184–9.

Nashar RM, Almurshed KS. Colorectal cancer: a case control study of dietary factors, king Faisal specialist hospital and research center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family and Community Medicine. 2008;15(2):57–64.

Tayyem RF, Bawadi HA, Shehadah I, AbuMweis SS, Agraib LM, Al-Jaberi T, Al-Nusairr M, Heath DD, Bani-Hani KE. Meats, milk and fat consumption in colorectal cancer. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(6):746–56.

Mahfouz EM, Sadek RR, Abdel-Latief WM, Mosallem FA, Hassan EE. The role of dietary and lifestyle factors in the development of colorectal cancer: case control study in Minia, Egypt. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22(4):215–22.

Rozen P, Lubin F, Papo N, Knaani J, Farbstein H, Farbstein M, Zajicek G. Calcium supplements interact significantly with long-term diet while suppressing rectal epithelial proliferation of adenoma patients. Cancer. 2001;91(4):833–40.

Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Beeson WL, Van den Brandt PA, Colditz GA, Folsom AR, Fraser GE, Freudenheim JL, Giovannucci E, et al. Dairy foods, calcium, and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(13):1015–22.

Lamprecht SA, Lipkin M. Cellular mechanisms of calcium and vitamin d in the inhibition of colorectal carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;952:73–87.

Newmark HL, Wargovich MJ, Bruce WR. Colon Cancer and dietary fat, phosphate, and calcium: a hypothesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;72(6):1323–5.

Sun Z, Wang PP, Roebothan B, Cotterchio M, Green R, Buehler S, Zhao J, Squires J, Zhao J, Zhu Y, et al. Calcium and vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: results from a large population-based case-control study in Newfoundland and Labrador and Ontario. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2011;102(5):382–9.

Vano YA, Rodrigues MJ, Schneider SM. Lien épidémiologique entre comportement alimentaire et cancer : exemple du cancer colorectal. Bulletin de Cancer. 2009;96:647–58.

Gonzalez CA, Riboli E. Diet and cancer prevention: contributions from the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(14):2555–62.

Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps. Cochrane Database systematic review. 2008;23(1)

Bassaganya-Riera J, Hontecillas R, Horne WT, Sandridge M, Herfarth HH, Bloomfeld R, Isaacs KL. Conjugated linoleic acid modulates immune responses in patients with mild to moderately active Crohn's disease. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:721–7.

Evans NP, Misyak SA, Schmelz EM, Guri AJ, Hontecillas R, Bassaganya-Riera J. Conjugated linoleic acid ameliorates inflammation-induced colorectal cancer in mice through activation of PPARgamma. J Nutr. 2010;140(3):515–21.

Kritchevsky D. Antimutagenic and some other effects of conjugated linoleic acid. Br J Nutr. 2000;83(5):459–65.

Van der Pols JC, Bain C, Gunnell D, Smith GD, Frobisher C, Martin RM. Childhood dairy intake and adult cancer risk: 65-y follow-up of the Boyd Orr cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(6):1722–9.

Ramesh C. Ray, Montet Didier: Microorganisms and fermentation of traditional foods: food biology series; 2014.

Atamian S, Olabi A, Kebbe Baghdadi O, Toufeili I. The characterization of the physicochemical and sensory properties of full-fat, reduced-fat and low-fat bovine, caprine, and ovine Greek yogurt (Labneh). Food Science and Nutrition. 2014;2(2):164–73.

Ajouz H, Mukherji D, Shamseddine A. Secondary bile acids: an underrecognized cause of colon cancer. World Journal Surgical Oncology. 2014;12

Behar J. Physiology and pathophysiology of the biliary tract: the gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi—a review. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2013;2013

Ou J, DeLany JP, Zhang M, Sharma S, O'Keefe SJ. Association between low colonic short-chain fatty acids and high bile acids in high colon cancer risk populations. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64(1):34–40.

Norat T, Chan D, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R. The associations between food, nutrition and physical activity and the risk of colorectal cancer. In. London: World Cancer Research Fund/American institute for. Cancer Res. 2010:225–7.

Acknowledgements

I thank infinitely Dr. Teresa Norat from the department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London for her pertinent remarks which helped me a lot in writing this article, I also thank Ms. Soukaina El kinany, a Phd student from the English department for her help in the revision of the manuscript and her great effort during the drafting.

Funding

No funding was received for this systematic review.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KE and MMSD conceived the study design, interpretation of the data, and wrote the manuscript. ZH contributed to the conception, the design of the study and the acquisition of data. BB contributed to the conception of the study, and the acquisition of data. KE supervised the data collection, contributed to the study design and to the data collection, and corrected the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is not required for this review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

El kinany, K., Deoula, M., Hatime, Z. et al. Dairy products and colorectal cancer in middle eastern and north African countries: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 18, 233 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4139-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4139-6