Abstract

Background

Only 5–10 % of breast cancer cases is linked to germline mutations in the BRCA-1 gene and occurs early in life. Conversely, sporadic breast tumors, which represent 90-95 % of breast malignancies, have lower BRCA-1 expression, but not mutated BRCA-1 gene, and tend to occur later in life in combination with other genetic alterations and/or environmental exposures. The latter may include environmental and dietary factors that activate the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). Therefore, understanding if changes in expression and/or activation of the AhR are associated with somatic inactivation of the BRCA-1 gene may provide clues for breast cancer therapy.

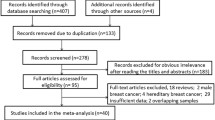

Methods

We evaluated Brca-1 CpG promoter methylation and expression in mammary tumors induced in Sprague–Dawley rats with the AhR agonist and mammary carcinogen 7,12-dimethyl-benzo(a)anthracene (DMBA). Also, we tested in human estrogen receptor (ER)α-negative sporadic UACC-3199 and ERα-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells carrying respectively, hyper- and hypomethylated BRCA-1 gene, if the treatment with the AhR antagonist α-naphthoflavone (αNF) modulated BRCA-1 and ERα expression. Finally, we examined the association between expression of AhR and BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation in human triple-negative (TNBC), luminal-A (LUM-A), LUM-B, and epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2)-positive breast tumor samples.

Results

Mammary tumors induced with DMBA had reduced BRCA-1 and ERα expression; higher Brca-1 promoter CpG methylation; increased expression of Ahr and its downstream target Cyp1b1; and higher proliferation markers Ccnd1 (cyclin D1) and Cdk4. In human UACC-3199 cells, low BRCA-1 was paralleled by constitutive high AhR expression; the treatment with αNF rescued BRCA-1 and ERα, while enhancing preferential expression of CYP1A1 compared to CYP1B1. Conversely, in MCF-7 cells, αNF antagonized estradiol-dependent activation of BRCA-1 without effects on expression of ERα. TNBC exhibited increased basal AhR and BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation compared to LUM-A, LUM-B, and HER-2-positive breast tumors.

Conclusions

Constitutive AhR expression coupled to BRCA-1 promoter CpG hypermethylation may be predictive markers of ERα-negative breast tumor development. Regimens based on selected AhR modulators (SAhRMs) may be useful for therapy against ERα-negative tumors, and possibly, TNBC with increased AhR and hypermethylated BRCA-1 gene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Germline mutations in the BRCA-1 gene confer a high probability of developing breast (~65 %) and ovarian (~40 %) tumors [1–6]. Breast tumors lacking BRCA-1 tend to be triple-negative (TNBC) basal-like characterized by reduced expression of estrogen receptor-α (ERα), progesterone receptor (PR), and epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) [7]. However, in spite of the high penetrance, BRCA-1 mutations explain only a small percentage (5-10 %) of breast tumor cases [8]. Sporadic breast tumors do not harbor somatic mutations in BRCA-1 but express low or undetectable BRCA-1 [9–13].

A mechanism that may contribute to reducing expression of BRCA-1 in sporadic breast cancers is epigenetic inactivation [14], which refers to modifications in DNA CpG methylation, histone posttranslational modifications, chromatin remodeling factors, and non-coding RNAs [15]. Various degrees of BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation have been observed in sporadic breast tumors [16] ranging from ~10 to 85 % depending on tumor type (ductal invasive > lobulo-alveolar) [17–23]. Causes contributing to BRCA-1 silencing remain largely unknown. Sporadic breast tumors tend to display characteristics of BRCA-1 mutation cancers (i.e. BRCAness) [24]. These include a high degree of correlation (~75 %) between hypermethylation of the BRCA-1 and ERα (ESR1) genes, and reduced expression of BRCA-1 and ERα [25–29]. Therefore, unraveling the cellular processes that place CpG methylation marks on the BRCA-1 gene [30] may assist with the formulation of therapies against loss of BRCA-1 expression in BRCA-1 mutation carriers [31] and non-BRCA-1 mutation patients [32].

Agonists of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) are ubiquitous in the environment and include dietary compounds, metabolites of fatty acids, industrial xenobiotics, and skin photoproducts generated through exposure to ultraviolet radiation [33]. Importantly, the expression of the AhR and downstream gene targets such as CYP1B1 are increased in human and rodent mammary tumors [34, 35]. Consequently, the use of selective modulators of the AhR (SAhRMs) has been proposed in breast cancer therapy [36].

Previously, we reported that AhR agonists repressed estradiol (E2)-dependent BRCA-1 transcription in human breast cancer cells [37–41]. This repressive effect was linked to increased recruitment to the BRCA-1 promoter of the activated AhR and other factors associated with the epigenetic machinery [42] including DNA methyl-transferase-1, (DNMT-1), DNMT-3a and -3b; methyl-binding domain protein-2 (MBD2); and placement of histone-3 trimethylation marks on lysine-9 (H3K9me3) [43]. In AhR-activated human breast cancer cells, the pattern of BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation [44] coincided with the one detected in human sporadic breast tumors [45, 46]. Recently, using a rodent model we found that gestational activation of the AhR increased CpG methylation of the Brca-1 gene while reducing BRCA-1 expression in mammary tissue of female offspring. The latter changes were overridden by gestational pretreatment with an AhR antagonist [47]. These cumulative data draw attention to the fact alterations of AhR expression and activity may play a role in the etiology of breast tumorigenesis. Nevertheless, the connection between higher AhR expression and/or activation and BRCA-1 promoter hypermethylation in breast tumors has not been investigated.

This study reports that rat mammary tumors induced with the AhR-agonist 7,12-dimethyl-benzo(a)anthracene (DMBA) [48] had augmented CpG methylation of the Brca-1 gene; higher expression of Ahr, Cyp1b, and proliferation markers (Cdk4, Ccnd1); and diminished expression of BRCA-1 and ERα. In cell culture experiments, the treatment with α-naphthoflavone (αNF), a prototype SAhRM, exerted cell line-specific effects: in ERα-negative human UACC-3199 sporadic breast cancer cell line, it rescued BRCA-1 and ERα expression, while inducing CYP1A1; in ERα-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells, αNF antagonized E2-dependent stimulation of BRCA-1 without affecting ERα expression. Finally, we document that human TNBC had higher AhR expression and BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation compared to human luminal-A (LUM-A), LUM-B, and HER-2-positive breast tumors. We conclude that constitutive high expression of AhR associated with BRCA-1 gene hypermethylation may be prognostic markers of ERα-negative breast tumor development. Therapies based on SAhRMs may hold promise for rescue of BRCA-1 and ERα expression in ERα-negative breast cancers.

Methods

Animal experiments

Weaned female Sprague–Dawley rats and AIN-76A diet were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Houston, Texas). At day 50 of age, 8 animals/group (n = 8) were assigned to either a sesame oil vehicle control group, or a treatment group receiving 10 mg/animal of DMBA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by oral gavage [48]. Animals were palpated weekly, and mammary tumors were collected when they reached a diameter of 1 cm. Animals were sacrificed according to a protocol approved by the IACUC Committee of the University of Arizona. Mammary gland tissues and tumors were collected and stored frozen until further analysis.

Cell culture experiments

Human MCF-7 and UACC-3199 breast cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). MCF-7 and UACC-3199 cells were maintained, respectively, in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Media (DMEM) or RPMI 1640 media (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT). αNF and E2 for cell culture experiments were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For experiments with αNF and E2, cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105/cells/well. Then, after 24 h cells were cultured for an additional 72 h in phenol-red free DMEM (MCF-7) or RPMI (UACC-3199) supplemented with 10 % charcoal-stripped FCS plus 2 μM αNF in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2 [42]. For Western blotting, at the end of the incubation period, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and scraped with cold lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor. For mRNA studies, at the end of the incubation period, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS. Extraction of RNA was carried out using Triazol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY). Cell extracts and RNA samples were stored frozen at -20 °C until further use.

Breast tumor collection

Human normal and breast tumor tissue sections were obtained de-identified from the University of Arizona Cancer Center Tissue Acquisition and Cellular/Molecular Analysis Shared Resource with the approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Arizona, Approval Form#F309. No patient-level correlations between gene activation information and individual patient-data were performed, according to U.S. Department of Human Health Services and Federal Drug Administration regulations, and in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html). The presence of tumor in each sample was confirmed by a staff pathologist and classified according to the following criteria: (i) TNBC: basal-like, and cytokeratin-, ERα-, PR-, HER-2-, and epidermal growth factor-negative; (ii) HER-2-positive: HER-2-positive and ERα-negative; (iii) LUM-A: ERα-positive and/or PR-positive, and HER-2-negative; and (iv) LUM-B: ERα-positive and/or PR-positive, and HER-2-positive. As controls, we also obtained sections of non-tumor tissue from the region surrounding TNBC and LUM-B tumors.

Western blot analyses

Western blot analyses were performed as previously described [47]. Immunoblotting was carried out with antibodies against human BRCA-1 (Cat. #9010); glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Cat. #2118) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); rat BRCA-1 (Cat. #sc-642); AhR (Cat. #sc-5579); and ERα (Cat. #sc-542) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Immunocomplexes were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK). The GAPDH protein was used as an internal control for normalization of protein expression.

Promoter CpG methylation

Measurements of rat Brca-1 promoter CpG methylation were carried out as described previously [47]. Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated from ~30 mg of mammary tissue using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Then, DNA (1 μg) was subjected to bisulfite modification using the CpGenome DNA Modification Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA). In preliminary experiments, we verified that the number of cycles for semiquantitative amplification of the rat Brca-1 promoter fragment with unmethylated (U)- and methylated (M)-specific primers was performed in the linear range (Fig. 2a). Then, the bisulfite-modified genomic DNA obtained from 8 animals/group (n = 8) was analyzed by PCR as follows: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min; 37 cycles at 95 °C for 45 s, 55 °C (U) and 59 °C (M) for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; and 1 cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. Briefly, reactions were carried out at a final volume of 25 μL consisting of the following master mix: bisulfite-modified DNA, JumpStart Taq DNA polymerase, 1X PCR buffer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 mM dNTPs, 1 μL each of forward and reverse primers. The PCR amplification products were separated on 2 % agarose gels and visualized using ethidium bromide staining. The rat Brca-1 amplicon was of the expected size (142 bp) and its authenticity to the rat Brca-1 gene [49] was confirmed by direct sequencing. The rat Brca-1 primers synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) were: U-sense: 5’-GTGAGAAGGTTTTTGTTGTATT-3’, and U-antisense: 5’-CCAATTCCAACATACATTACA-3’; M-sense: 5’-GCGAGAAGGTTTTTGTTGTATC-3’, and M-antisense: 5’-ACCAATTCCAACATACATTACG-3’.

Quantitative (qPCR) analysis of human BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation in control breast tissue and breast tumors was performed in bisulfonated genomic DNA using the following primers synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO): U-sense: 5'-TTGGTTTTTGTGGTAATGGAAAAGTGT-3', and U-antisense: 5'-CAAAAAATCTCAACAAACTCACACCA-3’; M-sense: 5’-TGGTAACGGAAAAGCG-3’, and M-antisense 5’-ATCTCAACGAACTCACGC-3’. The qPCR was carried out in a volume of 10 μL consisting of the following master mix: 5 μL of SYBER Green mix (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 1 μL each of forward and reverse primers, 2 μL nuclease-free water, and 1 μL of bisulfonated genomic DNA.

mRNA analyses

Sections of normal mammary gland and mammary tumor tissues from 8 animals/group (n = 8) were homogenized (1 mL/40 mg of tissue) of QIAzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was purified using RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit as per manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) [47]. Concentrations and quality of RNA were verified using the Nanodrop1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Equal amounts of total RNA (500 ng) were transcribed into cDNA using ISCRIPT supermix kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Next, cDNA aliquots were analyzed by qPCR using the SYBR Green PCR Reagents kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Briefly, reactions were run at a final volume of 25 μL consisting of the following master mix: 12.5 μL of SYBR Green mix, 1 μL each of forward and reverse primers, 9.5 μL nuclease-free water, and 1 μL cDNA. Amplification of Gapdh mRNA was used for normalization of transcript levels. The rat primer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) sequences were:

Ahr, sense: 5’-CTGGCAATGAATTTCCAAGGGAG-3’; 5’; antisense: CTTTCTCCAGTCTTAATCATGCG-3’; Cyp1a1, sense: 5’-GCCTTCACATCAGCCACAGA-3’, antisense: 5’-TTGTGACTCTAACCACCCAGAATC-3’; Cyp1b1, sense: 5’-TCAACCGCAACTTCAGCAACTTC-3’; antisense: 5-AGGTGTTGGCAGTGGTGGCAT-3’; Cdk4, sense: 5’-TGCAACGCCTGTGGATATGT-3’, antisense: 5’-CAGATTCCTCCATCTCCGGC-3’; Ccnd1 (cyclin D1), sense: 5’-CTGGCCATGAACTACCTGGA-3’, antisense: 5’-GTCACACTTGATCACTCTGG-3’; Gapdh, sense: 5’-TGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAAC-3’; antisense: 5’-AGGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA-3’. For cell culture experiments with human UACC-3199 breast cancer cells, the primer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) sequences were: BRCA-1, sense: 5′-AGCTCGCTGAGACTTCCTGGA-3′, antisense: 5′-CAATTCAATGTAGACAGACGT-3′; GAPDH, sense: 5’-ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTT-3’, antisense: 5’-CTCTTGTGCTCTTGCTGGG-3’; CYP1A1, sense: 5’-TAACATCGTCTTGGACCTCTTTG-3’, antisense: 5’-GTCGATAGCACCATCAGGGGT-3’; CYP1B1, sense: 5’-AACGTCATGAGTGCCGTGTGT-3’, antisense: 5’-GGCCGGTACGTTCTCCAAATC-3’. For AhR measurements in human breast tissues and tumors, primer sequences (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were: sense: 5’-GAAGCCGGTGCAGAAAACAG-3’, antisense: 5’-GCCGCTTGGAAGGATTTGAC-3’.

Statistical methods

Densitometry after Western blotting and CpG methylation analyses were performed using Kodak ID Image Analysis Software (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) [47]. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA. Post-hoc multiple comparisons among all means were conducted using Tukey’s Test after main effects and interactions were found to be significant at P ≤ 0.05. Data were presented as means ± SEM and statistical differences highlighted with different letters or asterisks.

Results

BRCA-1 expression in mammary tumors

Previous studies documented a high degree (~75 %) of correlation between loss of BRCA-1 and reduced ERα expression in human breast tumors [27, 28]. Results of BRCA-1 and ERα protein expression in control mammary tissue, and in adjacent normal mammary tissues and tumors obtained from animals treated with DMBA are presented in Fig. 1. Compared to control mammary gland, BRCA-1 expression (Fig. 1a) was reduced by an average 50 % in peritumoral mammary tissue (Fig. 1b). BRCA-1 protein levels were reduced by an additional ~40 % in DMBA-induced mammary tumors. Similarly, we found that compared to control mammary tissue, ERα levels were reduced by an average 40 % and 70 % respectively, in DMBA-treated but apparently normal mammary gland, and mammary tumors.

Expression of BRCA-1 and ERα are reduced in DMBA-induced mammary adjacent tissues and tumors. a Bands are representative immunocomplexes for BRCA-1 and ERα in control mammary gland, and mammary adjacent tissue and tumors obtained from four (1 through 4) DMBA-treated rats; b Bars represent means ± SEM of quantitation (fold change of control) of BRCA-1 and ERα protein corrected for GAPDH protein as internal standard in mammary adjacent tissues and tumors from 8 animals/group (n = 8). Different letters represent statistical differences (P < 0.05)

Brca-1 promoter CpG methylation in mammary tumors

To examine if the reduction in BRCA-1 expression in DMBA-treated animals was related to changes in Brca-1 promoter CpG methylation status, we extracted genomic DNA from control mammary gland, and adjacent mammary tissues and tumors from DMBA-treated animals. In control experiments, we ascertained that rat bisulfonated genomic DNA obtained from control mammary tissue was amplified in the linear range with U- and M-specific Brca-1 oligonucleotides, and Brca-1 amplicons were of the expected size (142 bp) (Fig. 2a). Turning to changes in Brca-1 promoter CpG methylation (Fig. 2b), we found that compared to control, the adjacent mammary gland isolated from DMBA-treated animals had an average 1.9-fold increase in Brca-1 promoter CpG methylation (Fig. 2c), which was increased on average an additional ~1.0-fold in DMBA-induced tumors (Fig. 2c). These data suggested that the Brca-1 gene was a target for repression via CpG methylation in mammary tissue of animals treated with the AhR agonist and mammary carcinogen, DMBA.

Brca-1 promoter methylation is increased in DMBA-induced rat mammary adjacent tissues and tumors. a Cycle number and no-template control (NTC) for amplification of rat Brca-1 promoter with U- and M-specific primers. MW, molecular weight markers; b Methylation status of Brca-1 promoter in control mammary gland, and in adjacent mammary tissues and tumors of four representative (1-4) animals; C) Quantitation from genomic DNA of Brca-1 promoter methylation status (M/U ratio) compared to control from 8 animals/group (n = 8). Means ± SEM without a common letter differ (P < 0.05)

AhR expression and activation in mammary tumors

Focusing on measurements of Ahr expression and activation, we first examined changes in Ahr in mammary tissue of control animals, and peritumoral and tumor tissues obtained from DMBA treated animals (Fig. 3). Compared to control, levels of Ahr were increased ~2.7-fold in peritumoral tissues; Ahr expression was increased an additional ~4.5-fold in DMBA-induced mammary tumors. In human breast cancer cell lines, higher CYP1B1 expression over CYP1A1 has been related to higher AhR expression and ERα-negative status [50]. Therefore, we measured changes in expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 as controls for AhR pathway activation. Basal Cyp1a1 was reduced by 30 and 70 % respectively in adjacent mammary gland and mammary tumors (Fig. 4a). Conversely, Cyp1b1 levels were markedly increased, on average ~5.0 and 14.0-fold of control, respectively in peritumoral tissue and mammary tumors (Fig. 4b). These data indicated that constitutive overexpression of the Ahr in rat mammary tumors was coupled with differential regulation on the Cyp1a1 (repression) and Cyp1b1 (activation) target genes.

Expression of Ahr is increased in DMBA-induced rat mammary adjacent tissues and tumors. Bars represent means ± SEM of quantitation (fold change of control) of Ahr mRNA corrected for Gapdh mRNA as internal standard in control and DMBA-induced adjacent mammary tissues and tumors from 8 animals/group (n = 8). Different letters represent statistical differences (P < 0.05)

Differential regulation of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 in DMBA-induced rat mammary adjacent tissues and tumors. Bars represent means ± SEM of quantitation (fold change of control) of (a) Cyp1a1 and (b) Cyp1b1 mRNA corrected for Gapdh mRNA as internal standard in control and DMBA-induced adjacent mammary tissues and tumors from 8 animals/group (n = 8). Different letters represent statistical differences (P < 0.05)

Proliferation markers in mammary tumors

Previous investigations documented that increased expression and activation of the AhR may be associated with mitogenic responses [51, 52], and increased Cdk4 levels in rat [47] and human [53] mammary cells. Based on this information, we compared Ccnd1 (cyclin D1) and Cdk4 expression in control mammary gland, and adjacent mammary tissues and tumors obtained from animals treated with DMBA (Fig. 5). We noticed that compared to control, in DMBA-treated animals levels of Cdk4 (Fig. 5a) and Ccnd1 (Fig. 5b) were increased respectively an average ~3.0- and 1.0-fold in adjacent mammary tissues; and an additional ~6.0- and 12.0-fold increase was seen, respectively, for Cdk4 and Ccnd1, in mammary tumors. Taken together, animal results suggested that constitutive high Ahr expression and pathway activation on the Cyp1b1 gene were linked to induction of mammary tumorigenesis associated with reduced expression of BRCA-1 and ERα.

Expression of Cdk4 and Ccnd1 (cyclin D1) are increased in DMBA-induced rat mammary adjacent tissues and tumors. Bars represent means ± SEM of quantitation (fold change of control) of (a) Cdk4 and (b) Ccnd1(cyclin D1) mRNA corrected for Gapdh mRNA as internal standard in control and DMBA-induced adjacent mammary tissues and tumors from 8 animals/group (n = 8). Different letters represent statistical differences (P < 0.05)

Targeting of AhR with αNF in human breast cancer cells

Increased expression and activation of the AhR may contribute to epigenetic remodeling during early breast carcinogenesis [54], whereas loss of BRCA-1 associates with ERα-negativity in hereditary and sporadic breast tumors [27]. Therefore, we compared the expression of BRCA-1 and AhR in human ERα-positive MCF-7, and ERα-negative UACC-3199 sporadic, breast cancer cells. We selected these cell lines because MCF-7 cells express wild-type BRCA-1 and are ERα-positive. Conversely, UACC-3199 cells have wild-type but hypermethylated, BRCA-1 [21, 55], and express low levels of ERα [56]. Results of Western blots informed that expression of BRCA-1 was ~5.0-fold higher in MCF-7 compared to UACC-3199 cells (Fig. 6a). Conversely, the expression of the AhR was notably higher (~15.0-fold) in UACC-3199 compared to MCF-7 cells.

Rescue of BRCA-1 and ERα expression in sporadic UACC-3199 breast cancer cells with αNF. a Bands are representative baseline immunocomplexes detected by Western blotting for BRCA-1 and AhR protein expression in MCF-7 and UACC-3199 breast cancer cells cultured respectively in control phenol-red free DMEM or RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10 % charcoal-stripped FCS; b UACC-3199 breast cancer cells were cultured in control phenol-red free RPMI plus 10 % charcoal-stripped FCS in the absence (control) or presence of αNF (2 μM for 72 h). Bars represent means ± SEM of quantitation of mRNA (fold change of control) performed twice in duplicate (n = 4) with four repeated measures/sample. BRCA-1 mRNA was corrected for GAPDH mRNA as internal standard; c Bands are immunocomplexes detected by Western blotting for BRCA-1 and ERα in UACC-3199 breast cancer cells cultured in phenol-red free RPMI plus 10 % charcoal-stripped FCS in the absence (control) or presence of αNF (2 μM for 72 h). GAPDH bands are internal standards for Western blotting; d Bars represent means ± SEM of quantitation of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 mRNA (fold change of control) performed twice in duplicate (n = 4) with four repeated measures/sample, and corrected for GAPDH mRNA as internal standard. In (b) and (d) Asterisks represent statistical differences (P < 0.05) compared to control

In previous studies with MCF-7 cells, we used αNF to reverse the repressive effects of AhR agonists on BRCA-1 expression [38]. We then extended these studies to UACC-3199 breast cancer cells. Results depicted in Fig. 6b revealed that the treatment with αNF increased (~1.4-fold of control) BRCA-1 mRNA; this change was associated with a ~2.0-fold upregulation of BRCA-1 and ERα expression (Fig. 6c). Turning to other biological changes that occurred in UACC-3199 cells along with reactivation of BRCA-1 by αNF, we detected a large increase (~32-fold of control) in CYP1A1 expression with only modest effects (~1.5-fold increase compared to control) on CYP1B1 (Fig. 6d). Then, we compared the effects of αNF on BRCA-1 and ERα expression in MCF-7 and UACC-3199 breast cancer cells. Results illustrated in Fig. 7 confirmed that αNF increased ~2.0- and 3.0-fold of control respectively, BRCA-1 and ERα in UACC-3199 cells, which were however refractory to the treatment with E2 alone or in combination with αNF. On the other hand, as previously reported by our group [41, 42], the treatment of MCF-7 cells with αNF antagonized the E2-dependent induction of BRCA-1. Overall, these cell culture studies implied that the effects of αNF, selected as a prototype AhR antagonist, were influenced by cell-context and ERα status, i.e. αNF rescued BRCA-1 and ERα expression in sporadic and ERα-negative UACC-3199 breast cancer cells carrying hypermethylated BRCA-1. Conversely, αNF antagonized E2-dependent stimulation of BRCA-1 expression in ERα-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Differential effects of αNF on BRCA-1 and ERα expression in MCF-7 and UACC-3199 breast cancer cells. Cells were cultured for 72 h in control phenol red-free media (DMEM for MCF-7; RPMI for UACC-31299) supplemented with 10 % charcoal-stripped FCS in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2, alone or in combination with 2 μM αNF. Bands are representative immunocomplexes detected by Western blotting for BRCA-1, ERα, and GAPDH from two independent experiments performed in duplicate (n = 4)

BRCA-1 promoter methylation and AhR expression in human breast tumors

Next, we wished to explore if differential expression of AhR and BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation associated with pathological classification of human breast tumor subtypes based on receptor status. Therefore, we compared the level of BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation in genomic DNA obtained from control breast tissue and various breast tumor subtypes including TNBC, LUM-A, HER-2-positive, and LUM-B. On average, we observed that BRCA-1 promoter methylation (M/U ratio) was increased ~6.6-fold in TBNC compared to non-tumor breast tissue (Fig. 8). Conversely, compared to non-tumor tissue, there were no differences in the amount of BRCA-1 promoter methylation in LUM-A, LUM-B, and HER-2-positive breast tumors. Interestingly, the increased BRCA-1 promoter methylation in TNBC correlated with increased expression (~3.0-fold of control) of AhR. Overall, these results denoted that coordinated increase in AhR expression and BRCA-1 gene hypermethylation may be molecular markers of TNBC.

Human TNBC harbor constitutive AhR expression and increased BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation. Bars represent quantitation of BRCA-1 promoter CpG methylation (M/U ratio) and AhR expression in human TNBC (n = 4), LUM-A (n = 5), LUM-B (n = 4), and HER-2-positive (n = 5) breast tumors. Asterisks represent statistical differences (P < 0.05) compared to non-tumor breast tissue control

Discussion

Earlier studies documented that the AhR is overexpressed and constitutively activate in rodent and human mammary tumors [35]. These findings attributed to environmental and endogenous factors that activate the AhR a role in breast tumorigenesis. Our prior cell culture [37–44] and rodent [47] model investigations of breast cancer provided evidence that the BRCA-1 gene was a molecular target for the AhR and various chromatin remodeling factors. Specifically, the recruitment of the activated AhR, DNMTs, and MBD-2 to the BRCA-1 gene culminated with placement of repressive histone (H3K9me3) and DNA (CpG methylation) marks, and downregulation of BRCA-1 expression.

The first objective of this study was to investigate the association between AhR expression and/or activation and Brca-1 promoter methylation status in mammary tumors. For this purpose, we adopted the DMBA-rat mammary tumor model based on the knowledge DMBA is a strong AhR agonist [33] and mammary carcinogen [48, 57]. The upregulation of Ahr and Cyp1b1 were paralleled by increased Brca-1 CpG methylation, and reduced expression of BRCA-1 and ERα in mammary tumors induced with DMBA. Also, the reduction in BRCA-1 expression observed in peritumoral tissue suggested that Brca-1 CpG methylation may be an epigenetic event that occurs prior to overt mammary tumor formation linked to Ahr overexpression and/or activation. This interpretation may have prognostic value since adjacent non-tumor mammary tissue from DMBA-treated animals had also increased expression of the proliferation markers Cdk4 and Ccnd1 (cyclin D1). Overall, results of animal experiments linked higher AhR expression and activity on the Cyp1b1 gene to increased risk of mammary tumorigenesis [34, 48, 54, 57, 58] via epigenetic silencing of Brca-1.

The reduction in ERα expression observed in adjacent mammary gland and mammary tumors of DMBA-treated animals was consistent with previous reports of reduced ERα in familial BRCA-1 tumors [25, 26], and sporadic breast cancers with hypermethylated BRCA-1 [28]. The ERα and the BRCA-1 participate in a positive feed-back loop whereby the ERα upregulates BRCA-1 [38], which in turn stimulates ERα expression [27]. Therefore, AhR-dependent repression of BRCA-1 via increased CpG methylation may disrupt this positive feedback loop between BRCA-1 and ERα and favor the development of ERα- and BRCA-1-negative breast tumors.

Turning to markers of AhR activation, we measured increased Cyp1b1 in adjacent mammary gland and mammary tumors of DMBA-treated animals. This accumulation was consistent with previous studies reporting stimulation of Cyp1b1 in rat models of mammary tumorigenesis [34, 48]. The CYP1B1 enzyme catalyzes the production from E2 of mutagenic 4-hydroxy-E2 (4OH-E2) [59, 60]. It is feasible that the constitutive activation of the AhR/CYP1B1 axis may have the synergistic effect of increasing DNA damage via increased production of mutagenic 4OH-E2 while impairing DNA repair functions controlled by BRCA-1. Conversely, we found that Cyp1a1 was reduced in adjacent mammary gland and mammary tumors of DMBA-treated animals. Consistent with these findings, earlier studies documented preferential repression of Cyp1a1 in DMBA-induced mammary tumors [48], as well as in human invasive ductal carcinomas [61, 62] and breast cancer cells lacking the ERα [50, 63]. Furthermore, reduced CYP1A1 enzymatic activity has been linked to constitutive activation of the AhR [64] and resistance of breast cancer cells to apoptosis induced by DMBA [65].

To further elucidate the cross-talk between expression and/or activation of AhR, and BRCA-1 regulation, we turned to cell culture experiments using UACC-3199 sporadic breast cancer cells, which possess hypermethylated BRCA-1 promoter [21, 55] and express low ERα [56]. Compared to MCF-7 cells, UACC-3199 cells had higher basal AhR, but lower BRCA-1. Therefore, we tested whether or not treatment of UACC-3199 cells with the AhR antagonist αNF rescued BRCA-1 expression. The rationale for this approach was based on our previous studies showing that BRCA-1 silencing by AhR agonists was reversed by cotreatment with α-NF [38]. The mechanisms of action of αNF as an AhR antagonist and anticarcinogen have been related respectively, to reduction of transcriptionally active nuclear AhR complexes [66, 67], and inhibition of 4OH-E2 production by CYP1B1 [68]. The rescue of BRCA-1 and ERα by αNF in UACC-3199 breast cancer cells were biological changes associated with preferential induction of CYP1A1. Conversely, αNF did not affect ERα levels, but antagonized E2-dependent activation of BRCA expression, in ERα-positive MCF-7 cells. The latter findings were in accord with our previous reports documenting repression by αNF and 3-methoxy-4-naphthoflavone, another antagonist of the AhR, of E2-dependent transcriptional activation of the BRCA-1 gene [42]. These differential effects of αNF on BRCA-1 and ERα expression could be attributed to interactions between agonist/antagonist activities on the AhR and ERα status [69]. This AhR-ERα cross-talk could be exploited for the development of strategies aimed at the reactivation of BRCA-1 and ERα in ERα-negative and AhR-overexpressing tumors.

We further extended our studies of BRCA-1/AhR cross-talk to human breast tumors, and found that compared to LUM-A, LUM-B, and HER-2-positive tumors, TNBC had higher AhR and BRCA-1 CpG methylation. These observations provided additional support to the hypothesis that constitutive AhR expression may be associated with hypermethylation of the BRCA-1 promoter and the development of TNBC. It remains unknown whether the reduced ERα expression in DMBA-induced tumors, UACC-3199 cells, and TNBC tumors may be due to hypermethylation, or disruption of expression of transcription factors that regulate transcription, of the ERα (ERS1) gene. Answering these queries may assist with the development of strategies for coordinate epigenetic reactivation of BRCA-1 and ESR1 in ERα-negative breast tissues.

Conclusions

Many studies have effectively utilized the AhR-agonist and mammary carcinogen DMBA to examine the molecular pathways that contribute to breast cancer and efficacy of therapies [57]. To our knowledge, this is the first study linking constitutive overexpression of the AhR to BRCA-1 promoter hypermethylation in DMBA-induced mammary tumors and human TNBC. The potential prognostic significance of the current findings is underscored by the fact the AhR is constitutively active in ERα-negative human breast tumor cells [34, 35, 50, 61]. Ongoing studies in our laboratory are using in vitro and vivo models to explore the effects of AhR knockout on epigenetic regulation of BRCA-1 and ESR1 (ERα), and the preventative effects of AhR antagonists. Progress in these areas may help clarifying a causative role for the AhR in breast tumorigenesis and assist with the development of risk models for BRCA-1 mutation carriers [70, 71] and sporadic TNBC, for which therapy options remains an intensive area of investigation [72, 73].

Abbreviations

- 4OH-E2:

-

4-hydroxy-estradiol

- AhR:

-

Aromatic hydrocarbon receptor

- αNF:

-

α-naphthoflavone

- DMBA:

-

7,12-dimethyl-benzo(a)anthracene

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Media

- DNMT:

-

DNA methyl-transferase

- E2:

-

Estradiol

- ERα:

-

Estrogen receptor-α

- FCS:

-

Fetal calf serum

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HER-2:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor-2

- H3K9me3:

-

Histone-3 trimethylated at lysine-9

- M: LOH:

-

Loss of heterozygosity

- LUM-A:

-

Luminal-A

- LUM-B:

-

Luminal-B

- MBD2:

-

Methyl-binding domain protein-2

- M:

-

Methylated specific primers

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- SAhRMs:

-

Selective modulators of the AhR

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

- qPCR:

-

quantitative PCR

- U:

-

Unmethylated specific primers

References

Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71.

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(3):676–89.

Levy-Lahad E, Friedman E. Cancer risks among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(1):11–5.

Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56(1):265–71.

Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2654–63.

Berchuck A, Heron KA, Carney ME, Lancaster JM, Fraser EG, Vinson VL, et al. Frequency of germline and somatic BRCA1 mutations in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(10):2433–7.

Gorski JJ, Kennedy RD, Hosey AM, Harkin DP. The complex relationship between BRCA1 and ERalpha in hereditary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(5):1514–8.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. http://www.cancer.gov. 2013. Accessed 13 July 2015.

Seery LT, Knowlden JM, Gee JM, Robertson JF, Kenny FS, Ellis IO, et al. BRCA1 expression levels predict distant metastasis of sporadic breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 1999;84(3):258–62.

Thompson ME, Jensen RA, Obermiller PS, Page DL, Holt JT. Decreased expression of BRCA1 accelerates growth and is often present during sporadic breast cancer progression. Nat Genet. 1995;9(4):444–50.

Yoshikawa K, Honda K, Inamoto T, Shinohara H, Yamauchi A, Suga K, et al. Reduction of BRCA1 protein expression in Japanese sporadic breast carcinomas and its frequent loss in BRCA1-associated cases. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(6):1249–61.

Taylor J, Lymboura M, Pace PE, A'hern RP, Desai AJ, Shousha S, et al. An important role for BRCA1 in breast cancer progression is indicated by its loss in a large proportion of non-familial breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 1998;79(4):334–42.

Wilson CA, Ramos L, Villaseñor MR, Anders KH, Press MF, Clarke K, et al. Localization of human BRCA1 and its loss in high-grade, non-inherited breast carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1999;21(2):236–40.

Butcher DT, Rodenhiser DI. Epigenetic inactivation of BRCA1 is associated with aberrant expression of CTCF and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT3B) in some sporadic breast tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(1):210–9.

Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome – biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(10):726–34.

Birgisdottir V, Stefansson OA, Bodvarsdottir SK, Hilmarsdottir H, Jonasson JG, Eyfjord JE. Epigenetic silencing and deletion of the BRCA1 gene in sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R38.

Dobrovic A, Simpfendorfer D. Methylation of the BRCA1 gene in sporadic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57(16):3347–50.

Magdinier F, Ribieras S, Lenoir GM, Frappart L, Dante R. Down-regulation of BRCA1 in human sporadic breast cancer; analysis of DNA methylation patterns of the putative promoter region. Oncogene. 1998;17(24):3169–76.

Magdinier F, Billard LM, Wittmann G, Frappart L, Benchaïb M, Lenoir GM, et al. Regional methylation of the 5' end CpG island of BRCA1 is associated with reduced gene expression in human somatic cells. FASEB J. 2000;14(11):1585–94.

Rice JC, Massey-Brown KS, Futscher BW. Aberrant methylation of the BRCA1 CpG island promoter is associated with decreased BRCA1 mRNA in sporadic breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1998;17(14):1807–12.

Rice JC, Ozcelik H, Maxeiner P, Andrulis I, Futscher BW. Methylation of the BRCA1 promoter is associated with decreased BRCA1 mRNA levels in clinical breast cancer specimens. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(9):1761–5.

Miyamoto K, Fukutomi T, Asada K, Wakazono K, Tsuda H, Asahara T, et al. Promoter hypermethylation and post-transcriptional mechanisms for reduced BRCA1 immunoreactivity in sporadic human breast cancers. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32(3):79–84.

Matros E, Wang ZC, Lodeiro G, Miron A, Iglehart JD, Richardson AL. BRCA1 promoter methylation in sporadic breast tumors: relationship to gene expression profiles. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91(2):179–86.

Lips EH, Mulder L, Oonk A, van der Kolk LE, Hogervorst FB, Imholz AL, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: BRCAness and concordance of clinical features with BRCA1-mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2172–7.

Foulkes WD, Metcalfe K, Sun P, Hanna WM, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. Estrogen receptor status in BRCA1- and BRCA2-related breast cancer: the influence of age, grade, and histological type. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(6):2029–34.

Lakhani SR, Reis-Filho JS, Fulford L, Penault-Llorca F, van der Vijver M, Parry S, et al. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Prediction of BRCA1 status in patients with breast cancer using estrogen receptor and basal phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(14):5175–80.

Hosey AM, Gorski JJ, Murray MM, Quinn JE, Chung WY, Stewart GE, et al. Molecular basis for estrogen receptor alpha deficiency in BRCA1-linked breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(22):1683–94.

Wei M, Xu J, Dignam J, Nanda R, Sveen L, Fackenthal J, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha, BRCA1, and FANCF promoter methylation occur in distinct subsets of sporadic breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(1):113–20.

Bal A, Verma S, Joshi K, Singla A, Thakur R, Arora S, et al. BRCA1-methylated sporadic breast cancers are BRCA-like in showing a basal phenotype and absence of ER expression. Virchows Arch. 2012;461(3):305–12.

DiNardo DN, Butcher DT, Robinson DP, Archer TK, Rodenhiser DI. Functional analysis of CpG methylation in the BRCA1 promoter region. Oncogene. 2001;20(38):5331–40.

Tapia T, Smalley SV, Kohen P, Muñoz A, Solis LM, Corvalan A, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of BRCA1 correlates with absence of expression in hereditary breast cancer tumors. Epigenetics. 2008;3(3):157–63.

Wong EM, Southey MC, Fox SB, Brown MA, Dowty JG, Jenkins MA, et al. Constitutional methylation of the BRCA1 promoter is specifically associated with BRCA1 mutation-associated pathology in early-onset breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4(1):23–33.

Denison MS, Nagy SR. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by structurally diverse exogenous and endogenous chemicals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:309–34.

Schlezinger JJ, Liu D, Farago M, Seldin DC, Belguise K, Sonenshein GE, et al. A role for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mammary gland tumorigenesis. Biol Chem. 2006;387(9):1175–87.

Yang X, Solomon S, Fraser LR, Trombino AF, Liu D, Sonenshein GE, et al. Constitutive regulation of CYP1B1 by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in pre-malignant and malignant mammary tissue. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104(2):402–17.

Safe S, Qin C, McDougal A. Development of selective aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulators for treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1999;8(9):1385–96.

Jeffy BD, Schultz EU, Selmin O, Gudas JM, Bowden GT, Romagnolo D. Inhibition of BRCA-1 expression by benzo[a]pyrene and its diol epoxide. Mol Carcinog. 1999;26(2):100–18.

Jeffy BD, Chen EJ, Gudas JM, Romagnolo DF. Disruption of cell cycle kinetics by benzo[a]pyrene: inverse expression patterns of BRCA-1 and p53 in MCF-7 cells arrested in S and G2. Neoplasia. 2000;2(5):460–70.

Jeffy BD, Chirnomas RB, Romagnolo DF. Epigenetics of breast cancer: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as risk factors. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2002;39(2-3):235–44.

Jeffy BD, Chirnomas RB, Chen EJ, Gudas JM, Romagnolo DF. Activation of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor pathway is not sufficient for transcriptional repression of BRCA-1: requirements for metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene to 7r,8t-dihydroxy-9t,10-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene. Cancer Res. 2002; 62(1):113-21.

Jeffy BD, Hockings JK, Kemp MQ, Morgan SS, Hager JA, Beliakoff J, et al. An estrogen receptor-alpha/p300 complex activates the BRCA-1 promoter at an AP-1 site that binds Jun/Fos transcription factors:repressive effects of p53 on BRCA-1 transcription. Neoplasia. 2005;7(9):873–82.

Hockings JK, Thorne PA, Kemp MQ, Morgan SS, Selmin O, Romagnolo DF. The ligand status of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor modulates transcriptional activation of BRCA-1 promoter by estrogen. Cancer Res. 2006;66(4):2224–32.

Papoutsis AJ, Lamore SD, Wondrak GT, Selmin OI, Romagnolo DF. Resveratrol prevents epigenetic silencing of BRCA-1 by the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor in human breast cancer cells. J Nutr. 2010;140(9):1607-14.

Papoutsis AJ, Borg JL, Selmin OI, Romagnolo DF. BRCA-1 promoter hypermethylation and silencing induced by the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor-ligand TCDD are prevented by resveratrol in MCF-7 cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23(10):1324–32.

Esteller M, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Bonilla F, Matias-Guiu X, Lerma E, et al. Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(7):564–9.

Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(4):286–98.

Papoutsis AJ, Selmin OI, Borg JL, Romagnolo DF. Gestational exposure to the AhR agonist 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induces BRCA-1 promoter hypermethylation and reduces BRCA-1 expression in mammary tissue of ratoffspring: preventive effects of resveratrol. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54(4):261–9.

Trombino AF, Near RI, Matulka RA, Yang S, Hafer LJ, Toselli PA, et al. Expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor/transcription factor (AhR) and AhR-regulated CYP1 gene transcripts in a rat model of mammary tumorigenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;63(2):117–31.

Bennett LM, Brownlee HA, Hagavik S, Wiseman RW. Sequence analysis of the rat Brca1 homolog and its promoter region. Mamm Genome. 1999;10(1):19–25.

Angus WG, Larsen MC, Jefcoate CR. Expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 depends on cell-specific factors in human breast cancer cell lines: role of estrogen receptor status. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(6):947–55.

Vaziri C, Schneider A, Sherr DH, Faller DV. Expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor is regulated by serum and mitogenic growth factors in murine 3T3 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(42):25921–7.

Kim DW, Gazourian L, Quadri SA, Romieu-Mourez R, Sherr DH, Sonenshein GE. The RelA NF-kappaB subunit and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) cooperate to transactivate the c-myc promoter in mammary cells. Oncogene. 2000;19(48):5498–506.

Barhoover MA, Hall JM, Greenlee WF, Thomas RS. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates cell cycle progression in human breast cancer cells via a functional interaction with cyclin-dependent kinase 4. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77(2):195–201.

Locke WJ, Zotenko E, Stirzaker C, Robinson MD, Hinshelwood RA, Stone A, et al. Coordinated epigenetic remodelling of transcriptional networks occurs during early breast carcinogenesis. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7(1):52.

Wei M, Grushko TA, Dignam J, Hagos F, Nanda R, Sveen L, et al. BRCA1 promoter methylation in sporadic breast cancer is associated with reduced BRCA1 copy number and chromosome 17 aneusomy. Cancer Res. 2005;65(23):10692–9.

Sappok A, Mahlknecht U. Ribavirin restores ESR1 gene expression and tamoxifen sensitivity in ESR1 negative breast cancer cell lines. Clin Epigenetics. 2011;3:8.

Russo J, Russo IH. Experimentally induced mammary tumors in rats. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;39(1):7–20.

Jenkins S, Rowell C, Wang J, Lamartiniere CA. Prenatal TCDD exposure predisposes for mammary cancer in rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23(3):391–6.

Liehr JG. Is estradiol a genotoxic mutagenic carcinogen? Endocr Rev. 2000;21(1):40–54.

Jefcoate CR, Liehr JG, Santen RJ, Sutter TR, Yager JD, Yue W, et al. Tissue-specific synthesis and oxidative metabolism of estrogens. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000;27:95–112.

Murray GI, Taylor MC, McFadyen MC, McKay JA, Greenlee WF, Burke MD, et al. Tumor-specific expression of cytochrome P450 CYP1B1. Cancer Res. 1997;57(14):3026–31.

McKay JA, Melvin WT, Ah-See AK, Ewen SW, Greenlee WF, Marcus CB, et al. Expression of cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 in breast cancer. FEBS Lett. 1995;374(2):270–2.

Spink DC, Spink BC, Cao JQ, DePasquale JA, Pentecost BT, Fasco MJ, et al. Differential expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in human breast epithelial cells and breast tumor cells. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(2):291–8.

Chang CY, Puga A. Constitutive activation of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(1):525–35.

Ciolino HP, Dankwah M, Yeh GC. Resistance of MCF-7 cells to dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced apoptosis is due to reduced CYP1A1 expression. Int J Oncol. 2002;21(2):385–91.

Merchant M, Krishnan V, Safe S. Mechanism of action of alpha naphthoflavone as an Ah receptor antagonist in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993;120(2):179–85.

Santostefano M, Merchant M, Arellano L, Morrison V, Denison MS, Safe S. alpha-Naphthoflavone-induced CYP1A1 gene expression and cytosolic aryl hydrocarbon receptor transformation. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;43(2):200–6.

Mense SM, Singh B, Remotti F, Liu X, Bhat HK. Vitamin C and alpha-naphthoflavone prevent estrogen-induced mammary tumors and decrease oxidative stress in female ACI rats. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1202–8.

Zhang S, Qin C, Safe SH. Flavonoids as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: effects of structure and cell context. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(16):1877–82.

Ghadirian P, Narod S, Fafard E, Costa M, Robidoux A, Nkondjock A. Breast cancer risk in relation to the joint effect of BRCA mutations and diet diversity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117(2):417–22.

Jacot W, Thezenas S, Senal R, Viglianti C, Laberenne AC, Lopez-Crapez E, et al. BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation, 53BP1 protein expression and PARP-1 activity as biomarkers of DNA repair deficit in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):523.

Romagnolo DF, Zempleni J, Selmin OI. Nuclear receptors and epigenetic regulation: opportunities for nutritional targeting and disease prevention. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(4):373–85.

Romagnolo AP, Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. BRCA1 as target for breast cancer prevention and therapy. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;15(1):4–14.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical assistance of Jamie Borg in tissue collection and analysis. This work was supported by grants from the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (QSR14082995) and the US Department of Defense Breast Cancer Program (BC134119). Frozen tissue samples were provided by the UACC Cancer Biorepository (PI: S. Chambers), a part of the University of Arizona Cancer Center’s Tissue Acquisition and Cellular/Molecular Analysis Shared Resource (TACMASR), NIH CA023074.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

OIS, AJP, and DFR contributed to the conception and design of animal experiments, collection of animal tissues and analyses, and cell culture experiments. CL contributed to the collection of human breast tumors and tumor data interpretation. DFR and OIS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Romagnolo, D.F., Papoutsis, A.J., Laukaitis, C. et al. Constitutive expression of AhR and BRCA-1 promoter CpG hypermethylation as biomarkers of ERα-negative breast tumorigenesis. BMC Cancer 15, 1026 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-2044-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-2044-9