Abstract

Purpose

To explore the relationships between second-trimester anthropometric obesity indicators and cesarean section (CS).

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted at West China Second University Hospital, utilizing electronic health records from 15,304 pregnant women who received routine prenatal care and delivered between January 2021 and June 2022. Second-trimester anthropometric indicators, including body roundness index (BRI), body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage (BFP), and waist circumference (WC), were measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). Logistic regression models were employed to assess the associations between these indicators and CS risk, with additional subgroup analyses based on maternal age and fetal sex.

Results

The mean maternal age was 30.13 years. After adjusting for covariates, BRI (OR 1.22, 95%CI 1.15–1.30), BMI (OR 1.07, 95%CI 1.05–1.08), BFP (OR 1.03, 95%CI 1.02–1.04), and WC (OR 1.02, 95%CI 1.01–1.03) were all significantly associated with CS. Stratified analyses based on maternal age and fetal sex further confirmed these independent associations.

Conclusion

Second-trimester BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC were all significantly associated with CS risk, with BRI potentially demonstrating the strongest independent correlation. An integrated approach incorporating BMI and WC is recommended for CS risk, particularly in time-sensitive or resource-limited settings. The effect of anthropometric changes during pregnancy on CS may be explored in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) is required in some circumstances to protect the health of women and babies [1, 2]. Globally, 21.1% of women give birth by CS and the rates continue to increase [3, 4]. In China, the CS rate remains notably high, reaching 49.76% between 2016 and 2019 [5]. However, the overuse of CS without a medical indication has shown no benefit and may result in harm and waste of human and financial resources [6]. Studies have shown that CS has short-term and long-term effects on the health of both women and children [7]. Short-term risks of CS include reduced neonatal gut microbiome diversity [8], asthma [9], maternal uterine rupture [10], and severe acute morbidity [7]. Long-term risks involve increased risk of subsequent fertility [9], pelvic adhesions [11], higher hazard of anal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse [12], and later childhood obesity [9]. Therefore, reducing unnecessary CS is a global concern and a challenge in public health, and finding simple anthropometric indicators related to CS is of great significance for optimizing the overuse of CS.

It is estimated that 4.28 million pregnant women in China are affected by overweight and obesity [13, 14]. Maternal obesity during the second trimester, including its early phase, has been strongly associated with an increased risk of CS, highlighting the need for reliable obesity indicators for prenatal risk assessment as pregnancy progresses. Several key obesity indicators have been frequently discussed in the context of preventable CS. Body mass index (BMI), the standard measure of general obesity (weight[kg]/height[m2]) [15], has been widely studied, with previous studies demonstrating an increased risk of CS in individuals with abnormal BMI [16, 17]. However, BMI does not account for abdominal obesity or fat distribution [18]. Subcutaneous fat thickness (SCFT), a surrogate measure of central obesity [19], has demonstrated superior predictive value over BMI in CS risk assessment in large prospective and retrospective cohort studies [20, 21], yet its clinical utility is constrained by the complexity of measurement [22]. Waist circumference (WC) provides a simpler alternative for assessing central obesity [23, 24], but its relationship with CS risk remains underexplored. Similarly, body fat percentage (BFP) offers a more comprehensive measure of adiposity [25, 26], though its predictive superiority over BMI and WC is uncertain. The body roundness index (BRI), a novel metric estimating visceral and total body fat distribution [27, 28], has not yet been investigated in relation to CS risk. Given the unique characteristics of each anthropometric indicator and the limited research on their associations with CS, a comprehensive evaluation is warranted to identify an optimal predictor that can compensate for the limitations of individual measures.

This study aims to assess the associations between early-second-trimester BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC, measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and CS risk in Chinese pregnant women. Additionally, considering the established influence of maternal age and fetal sex on CS incidence [29, 30], stratified analyses were performed to evaluate their potential modifying effects on these associations.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective study utilizing data extracted from the information system in West China Second University Hospital at Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China. Chengdu is the most densely populated area in Sichuan Province with a 100% urbanization rate [31]. The targeted hospital is the industry-leading West China Women’s and Children’s Hospital, where the Department of Obstetrics has been rated as the National Key Development of Clinical Specialty responsible for maternal delivery from Chengdu to southwest China [32], ensuring a representative sample of pregnant women.

Participants

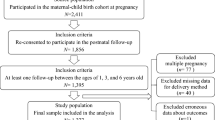

A total of 25,515 mothers who completed regular prenatal care and gave birth at the targeted hospital between January 2021 to June 2022 were screened for eligibility. Detailed inclusion criteria of our study were as follows: pregnant women completed regular antenatal care in the targeted hospital; aged 18 years or over; singleton pregnancy; underwent a body composition assessment in the second trimester; and gave birth at the targeted hospital. Cases with the following conditions were excluded: clearly defined medical indications for CS, such as fetal distress, contracted pelvis, malpresentation, placenta previa, etc [33, 34].; pre-existing diseases and conditions that would potentially influence delivery, for example, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid disorders, virus infection, and tuberculosis; delivery gestation<37 weeks or ≥ 42 weeks; presence in any mental disorders; with missing data. Finally, 14,381 participants were included in our data analysis with 9780 cases undergoing vaginal delivery (VD) and the other 4673 undergoing CS. Figure 1 is an overview of the flow of our participants. No significant difference was found in obesity indices and obstetric variables between women included in the study and those who were not.

Data extraction and definition of variables

We retrieved data from electronic medical records (EMRs) in the hospital information system (HIS) [35, 36], following a structured process to ensure data integrity and accuracy. First, our research team defined the study variables based on the research objectives. A designated team of hospital information technology (IT) engineers then extracted these variables from the HIS according to the predefined criteria. Once extracted, our research team integrated and standardized the dataset, rigorously reviewing the completeness and consistency of the records. Cases with missing or implausible values were flagged and removed based on predefined exclusion criteria. To further ensure data accuracy, we performed random sampling checks, cross-verifying the extracted records against the original EMRs. All data were securely stored in a protected database, ensuring that maternal privacy information was excluded to maintain confidentiality. The final dataset was used exclusively for statistical analyses related to this study.

Data extracted included basic information, delivery mode, anthropometric information, and clinical obstetric and neonatal information. The delivery mode was classified into VD and CS. Basic information included maternal age (years), ethnicity (categorized as Han or Minorities), height (cm), weight (kg), gravidity (times), and parity (times). Anthropometric information measured during the early-second trimester (13–15 weeks of gestation), involving BMI, BFP, and WC. And BRI was calculated using height and WC [27, 28]. Clinical obstetric and neonatal data encompassed gestational weight gain (kg), birthweight (g), and fetal sex (divided into boy or girl).

Ethic consideration

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University (Approval Code: 2015122; Approval Date: April 15, 2015).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with statistical significance set at p<0.05 (two-tailed). Continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as proportions.

To examine the associations between obesity indices and CS, we performed the following analyses: First, univariate analyses using independent samples t-test (for continuous variables) and χ2 test (for categorical variables) were used to compare differences between VD and CS groups; Second, four separate multivariable logistic regression models were constructed, each using one of the obesity indices (BRI, BMI, BFP, or WC) as the primary exposure variable. These models estimated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between each obesity index and CS, adjusted for covariates, including variables with a p-value < 0.1 in the univariable analysis and clinically relevant factors identified in the literature. To address multicollinearity, the obesity indices were not adjusted for one another (e.g., the BMI model excluded WC, BRI, and BFP as covariates); To further support the multivariable findings, subgroup analyses were performed by maternal age and fetal sex.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Mean ± SD, or n (%) for participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of all the 14,381 women, 9708 (67.51%) underwent VD, and 4673 (32.49%) opted for CS. The mean age of mothers in the sample was 30.13 (SD: 3.37) years, with 291 (2.02%) identifying as ethnic minorities. The average value of BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC were 3.14 (SD:0.77), 21.71 (SD: 2.63), 31.14 (SD: 4.97), and 78.30 (SD: 6.87), respectively. Women who underwent CS exhibited higher BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC were more likely to give birth to larger babies.

Univariable analysis of delivery mode (VD vs. CS)

Univariable analysis revealed significant differences between VD and CS groups for all variables except ethnicity and weight (Table 1). The CS group comprised older women (30.24 ± 3.36 vs. 30.08 ± 3.38 years, p<0.01) with shorter stature (160.00 ± 4.86 vs. 160.81 ± 4.85 cm, p<0.01), along with reduced gravidity (1.77 ± 1.09 vs. 1.87 ± 1.11 times, p<0.001) and parity (0.79 ± 0.55 vs. 1.02 ± 0.66 times, p<0.001) compared to those who had VD. In terms of neonatal characteristics, CS-delivered infants exhibited higher birthweight (3390.12 ± 408.60 vs. 3279.28 ± 355.10 g, p<0.001), with male predominance (56.69% vs. 43.31%, p<0.001). Notably, the CS group presented elevated obesity indicators, including BRI (3.25 ± 0.79 vs. 3.11 ± 0.76, p<0.001), BMI (21.92 ± 2.72 vs. 21.61 ± 2.58 kg/m2, p<0.001), BFP (31.64% vs. 30.91%, p<0.001), and WC (78.65 ± 7.01 vs. 78.15 ± 6.80 cm, p<0.001). Additionally, women who underwent CS tended to have a higher body weight compared to those who had VD (56.15 ± 7.70 vs. 55.91 ± 7.38, p = 0.066), suggesting a potential association despite not reaching statistical significance.

Associations between maternal BMI, WC, BFP, and CS of women in second trimester

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariable regression analysis. BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC were associated with CS (BRI: OR 1.24, 95CI% 1.17–1.32; BMI: OR 1.06, 95%CI 1.04–1.08; BFP: OR 1.04, 95%CI 1.03–1.05; WC: OR 1.02, 95%CI 1.01–1.02). After adjusting for covariates, BRI continued to exhibit a stronger correlation with CS (BRI: OR 1.22, 95CI% 1.15–1.30; BMI: OR 1.07, 95%CI 1.05–1.08; BFP: OR 1.03, 95%CI 1.02–1.04; WC: OR 1.02, 95%CI 1.01–1.03).

Stratified analyses

The results of the regression analysis stratified by maternal age and fetal sex are shown in Table 3. After adjusting for covariates, BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC were the significant estimators of CS in both normal age group (18–34 years) and advanced maternal age group (≥ 35 years), as well as in both male and female groups (all p < 0.001).

Discussion

This retrospective study examined the association between adiposity indices (BRI, BMI, BFP, WC) and CS risk in the second trimester, with stratified analyses by maternal age and fetal sex. Our findings highlight three key insights: (1) BRI outperformed traditional obesity metrics in relation to CS; (2) second-trimester BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC were interchangeable anthropometric indicators for CS risk assessment; (3) integrating BMI (general obesity) and WC (central obesity) may offer a simple yet effective approach to reflect CS risk.

Associations between BRI, BMI, BFP, WC, and CS

This study establishes significant associations between BRI, BFP, WC, and CS risk in the second trimester. Our findings showed a significant correlation between WC and the risk of CS, aligning with prior research suggesting that central obesity indicators, such as SCFT, contribute to an elevated CS risk [18, 20] and further supporting earlier evidence that pre-pregnancy WC independently predicts CS likelihood [37]. Given the limited evidence on second-trimester WC, our findings reinforce the importance of monitoring central adiposity during pregnancy, and support reinforce recommendations from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity regarding the routine inclusion of WC in obesity assessments [38]. Importantly, both BRI and BFP emerged as independent indicators of CS risk even after adjusting for covariates. To our knowledge, no previous studies have explored the relationships between second-trimester BRI, BFP, and CS, highlighting the originality of our findings.

Consistent with previous studies, our results confirm that higher second-trimester BMI correlates with increased CS risk. For instance, an analysis of 4,455 pregnant women enrolled for Care at Freestanding Birth Centers in the United States revealed that women with higher BMI in the second trimester had significantly higher CS rates [39], which is similar to the findings of published retrospective studies in Sweden and Australia [40, 41], and a prospective cohort study including 997 women [18]. However, our findings contrast with an online survey suggesting that high BMI does not influence women’s decision-making regarding CS [42], this discrepancy may stem from subjective underestimation of weight status among participants [43].

Among all indices, BRI showed the strongest indicator for CS risk in this study, followed by BMI, BFP, and WC. However, its complex computation may limit its clinical applicability. Similarly, BFP also poses practical measurement challenges in obstetric settings despite its high relevance to CS [44]. And although BMI being the second strongest indicator, previous research has shown that concentrated fat distribution is associated with a higher risk than BMI itself [45], while WC is a more accurate measure of visceral adipose tissue than BMI and can capture the risks associated with both general and central obesity [46, 47]. However, other studies have suggested that the incidence of high WC always peaks later than BMI, and WC may not suitable for estimating obesity based on weight gain [48, 49]. Therefore, an integrated approach combining BMI and WC may better assess CS risk comprehensively.

Overall, our study advances the understanding of obesity-related CS risk by integrating multiple anthropometric indicators, including BMI (general obesity), WC (central obesity), BFP (total body fat), and BRI (fat distribution). This multi-indicator approach compensates for the limitations of individual measures, as each metric captures distinct aspects of body composition. Notably, our findings reveal a differential association strength among these indicators, with BRI showing the strongest association with CS risk, followed by BMI, BFP, and WC. This comprehensive comparison not only enhances risk stratification but also provides a nuanced perspective on the role of fat distribution in CS risk assessment, offering valuable insights into an understudied area.

Associations between BRI, BMI, BFP, WC, and CS stratified by maternal age and fetal sex

Stratification by maternal age revealed stronger associations between adiposity indices (BRI, BMI, BFP, WC) and CS in the advanced maternal age (AMA) group, with the risk increasing further after adjusting for covariates. This aligns with prior research showing that CS rates nearly double with increasing maternal age [50, 51], potentially due to diminished uterine contractility in AMA women [50]. Regarding fetal sex, male infants were associated with higher CS risk than female infants, even after adjustment [29]. This consolidates the findings of a study estimating the association between fetal sex and adverse birth outcomes in a large cohort of women in Taiwan, China [52], possibly due to the greater birthweight and head circumference of male fetuses than that of female [53].

Associations between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and CS

Consistent with the findings of African Demographic and Health Survey with a large sample [54], we found that shorter maternal height was associated with an increase in CS. Unlike previous research suggesting no association between parity and CS [55], increasing parity were associated with lower CS rates in our study, which differs from a study on obstetric outcomes of singleton women showing that parity is not associated with CS [56]. This may be related to the different statistical methods and participants of the two studies, and further research on the relationship between parity and CS is needed. Additionally, higher birthweight was also correlated with the elevated CS risk, which reinforces previous findings [57], possibly due to obesity-induced risk of macrosomia [58].

Clinical implications

Our findings highlight the value of integrating multiple anthropometric indicators (BRI, BMI, BFP, WC) for CS risk assessment, rather than relying solely on BMI. Given the varying strengths of these indicators, a multi-metric approach may refine risk stratification and enhance individualized perinatal care. For practical clinical applications, we suggest combining BMI (general obesity) and WC (central obesity) for CS risk assessment, especially in settings where advanced measurements like BRI or BFP are less accessible.

Additionally, our results highlight the importance of early identification of high-risk subgroups, such as older mothers and those carrying male fetuses. By incorporating maternal age, fetal sex, and obesity-related indicators into routine prenatal care, clinicians could optimize delivery planning and develop targeted interventions, which would lead to a more personalized and evidence-based approach. Future research should explore how these obesity indices can be integrated into clinical decision-making and preventive frameworks to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes [59].

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to comprehensively examine the associations between BRI, BFP, WC, and CS risk during the second trimester using a large sample and multiple obesity-related metrics. Notably, our results indicated the relative strength of association with CS risk, from highest to lowest: BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC, providing valuable initial evidence for the potential predictive power of these metrics and contributing to a comprehensive assessment of the adverse effects of maternal obesity on CS.

Certain limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the study was conducted at a single center, and our study population consisted almost exclusively of Han women, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, our study was based on hospital database records, which included only a limited set of sociodemographic variables. Due to the large sample size, additional participant characteristics such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors, and detailed medical history could not be further assessed, which may have influenced the stability of our findings and should be considered when interpreting the results. Third, anthropometry during pregnancy is constantly changing, so the findings need to be further supported by long-term longitudinal studies. Fourth, observational design cannot establish causality and provide clear mechanisms to explain our findings, thus further research is required to deepen understanding of the role of anthropometry in CS. Finally, our dataset did not distinguish between elective and emergency CS, which could have provided further insights into the relationship between BMI and delivery mode decisions. Future research could explore this distinction to better understand its influences.

Conclusion

BRI, BMI, BFP, and WC in the second trimester were performed similarly in estimating CS, and BRI was a better indicator of CS risk, followed by BMI, BFP, and WC, even after adjusting for covariates and conducting stratified analyses. Given the practical limitations of certain metrics, an integrated approach incorporating BMI and WC is recommended as a feasible and effective strategy for CS risk assessment in clinical settings. Future research should explore the longitudinal impact of maternal adiposity changes on delivery outcomes and develop accessible clinical tools for integrating these anthropometric indicators into routine obstetric care to enhance perinatal risk stratification and improving maternal health outcomes.

Data availability

Data availability: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BIA:

-

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- CS:

-

Cesarean section

- VD:

-

Vaginal delivery

- BRI:

-

Body roundness index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BFP:

-

Body fat percentage

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- SCFT:

-

Subcutaneous fat thickness

- EMRs:

-

Electronic medical records

- HIS:

-

Hospital information system

References

Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(6):e005671.

Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, Barros AJ, Barros FC, Juan L, Moller AB, Say L, Hosseinpoor AR, Yi M, Neto DD. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1341–8.

Lancet T. Stemming the global caesarean section epidemic. Lancet (London England). 2018;392(10155):1279.

Betrán AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM, Aleem HA, Althabe F, Bergholt T, De Bernis L, Carroli G, Deneux-Tharaux C, Devlieger R. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. 2015;123(5):667.

Song C, Xu Y, Ding Y, Zhang Y, Liu N, Li L, Li Z, Du J, You H, Ma H, ** G. The rates and medical necessity of Cesarean delivery in China, 2012–2019: an inspiration from Jiangsu. BMC Med. 2021;19:1–0.

Opiyo N, Kingdon C, Oladapo OT, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Bonet M, Bucagu M, Portela A, McConville F, Downe S, Gülmezoglu AM. Non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections: WHO recommendations. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;98(1):66.

Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, Mola G, Visser GH, Homer CS, Gibbons D, Kelly NM, Kennedy HP, Kidanto H, Taylor P. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1349–57.

Hanachi M, Maghrebi O, Bichiou H, Trabelsi F, Bouyahia NM, Zhioua F, Belghith M, Harigua-Souiai E, Baouendi M, Guizani-Tabbane L, Benkahla A. Longitudinal and comparative analysis of gut microbiota of Tunisian newborns according to delivery mode. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:780568.

Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with Cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002494.

Hautakangas TM, Uotila JT, Huhtala HS, Palomäki OL. How does uterine contractile activity affect the success of trial of labour after caesarean section, and the risk of uterine rupture? An exploratory, blinded analysis of a cohort from a randomised controlled trial. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;129(6):976–84.

Hesselman S, Högberg U, Råssjö EB, Schytt E, Löfgren M, Jonsson M. Abdominal adhesions in gynaecologic surgery after caesarean section: a longitudinal population-based register study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;125(5):597–603.

Blomquist JL, Muñoz A, Carroll M, Handa VL. Association of delivery mode with pelvic floor disorders after childbirth. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2438–47.

Chen C, Xu X, Yan Y. Estimated global overweight and obesity burden in pregnant women based on panel data model. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202183.

Feng Y, Shi C, Zhang C, Yin C, Zhou L. Effect of the smartphone application on caesarean section in women with overweight and obesity: a randomized controlled trial in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):746.

Caballero B. Humans against obesity: who will win? Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S4–9.

Szewczyk Z, Weaver N, Rollo M, Deeming S, Holliday E, Reeves P, Collins C. Maternal diet quality, body mass index and resource use in the perinatal period: an observational study. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3532.

Song Z, Cheng Y, Li T, Fan Y, Zhang Q, Cheng H. Effects of obesity Indices/GDM on the pregnancy outcomes in Chinese women: A retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1029978.

Eley V, Sekar R, Chin A, Donovan T, Krepska A, Lawrence M, Marquart L. Increased maternal abdominal subcutaneous fat thickness and body mass index are associated with increased Cesarean delivery: a prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(2):196–204.

Martin AM, Berger H, Nisenbaum R, Lausman AY, MacGarvie S, Crerar C, Ray JG. Abdominal visceral adiposity in the first trimester predicts glucose intolerance in later pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1308–10.

Kennedy NJ, Peek MJ, Quinton AE, Lanzarone V, Martin A, Benzie R, Nanan R. Maternal abdominal subcutaneous fat thickness as a predictor for adverse pregnancy outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;123(2):225–32.

Suresh A, Liu A, Poulton A, Quinton A, Amer Z, Mongelli M, Martin A, Benzie R, Peek M, Nanan R. Comparison of maternal abdominal subcutaneous fat thickness and body mass index as markers for pregnancy outcomes: A stratified cohort study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(5):420–6.

Bazzocchi A, Filonzi G, Ponti F, Sassi C, Salizzoni E, Battista G, Canini R. Accuracy, reproducibility and repeatability of ultrasonography in the assessment of abdominal adiposity. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(9):1133–43.

Frank AP, de Souza Santos R, Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Determinants of body fat distribution in humans May provide insight about obesity-related health risks. J Lipid Res. 2019;60(10):1710–9.

Holmes CJ, Racette SB. The utility of body composition assessment in nutrition and clinical practice: an overview of current methodology. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2493.

Wu CJ, Kao TW, Chen YY, Yang HF, Chen WL. Peripheral fat distribution versus waist circumference for predicting mortality in metabolic syndrome. Diab/Metab Res Rev. 2019;35(4):e3116.

Nohr EA, Vaeth M, Baker JL, Sørensen TI, Olsen J, Rasmussen KM. Combined associations of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1750–9.

Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, Mueller M, Shen W, Gallagher D, Maeda Y, McDougall A, Peterson CM, Ravussin E, Heymsfield SB. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity. 2013;21(11):2264–71.

Zhang X, Ma N, Lin Q, Chen K, Zheng F, Wu J, Dong X, Niu W. Body roundness index and all-cause mortality among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2415051.

Al-Qaraghouli M, Fang YM. Effect of fetal sex on maternal and obstetric outcomes. Front Pead. 2017;5:144.

Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):911–9.

OfficeSPPsGG. https://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/11555/11563/2022/3/31/1d001c516b5d4b88ab5f6f35b3432518.shtml 2022.

West China Second University Hospital SU. https://www.motherchildren.com/intro_introduce/ 2023.

Elnakib S, Abdel-Tawab N, Orbay D, Hassanein N. Medical and non-medical reasons for Cesarean section delivery in Egypt: a hospital-based retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–1.

Begum T, Rahman A, Nababan H, Hoque DM, Khan AF, Ali T, Anwar I. Indications and determinants of caesarean section delivery: evidence from a population-based study in matlab, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0188074.

Kc A, Ewald U, Basnet O, Gurung A, Pyakuryal SN, Jha BK, Bergström A, Eriksson L, Paudel P, Karki S, Gajurel S. Effect of a scaled-up neonatal resuscitation quality improvement package on intrapartum-related mortality in Nepal: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9):e1002900.

Liao S, **ong A, **ong S, Zuo Y, Wang Y, Luo B. Associations between maternal body composition in the second trimester and premature rupture of membranes: a retrospective study using hospital information system data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2025;25:241.

Gao X, Yan Y, **ang S, Zeng G, Liu S, Sha T, He Q, Li H, Tan S, Chen C, Li L. The mutual effect of pre-pregnancy body mass index, waist circumference and gestational weight gain on obesity-related adverse pregnancy outcomes: A birth cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0177418.

Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, Santos RD, Arsenault B, Cuevas A, Hu FB, Griffin BA. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a consensus statement from the IAS and ICCR working group on visceral obesity. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2020;16(3):177–89.

Jevitt CM, Stapleton S, Deng Y, Song X, Wang K, Jolles DR. Birth outcomes of women with obesity enrolled for care at freestanding birth centers in the united States. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2021;66(1):14–23.

Bjorklund J, Wiberg-Itzel E, Wallstrom T. Is there an increased risk of Cesarean section in obese women after induction of labor? A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0263685.

Neal K, Ullah S, Glastras SJ. Obesity class impacts adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes independent of diabetes. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:832678.

Walędziak M, Różańska-Walędziak A. Does obesity influence women’s decision making about the mode of delivery?? J Clin Med. 2022;11(23):7234.

Khair H, Bataineh MA, Zaręba K, Alawar S, Maki S, Sallam GS, Abdalla A, Mutare S, Ali HI. Pregnant women’s perception and knowledge of the impact of obesity on prenatal outcomes—a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2023;15(11):2420.

Silveira EA, Barbosa LS, Noll M, Pinheiro HA, de Oliveira C. Body fat percentage prediction in older adults: agreement between anthropometric equations and DXA. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(4):2091–9.

Heitmann BL, Lissner L. Hip hip Hurrah! hip size inversely related to heart disease and total mortality. Obes Rev. 2011;12(6):478–81.

Cameron AJ, Magliano DJ, Söderberg S. A systematic review of the impact of including both waist and hip circumference in risk models for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and mortality. Obes Rev. 2013;14(1):86–94.

Cameron AJ, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Carstensen B, Alberti KG, Tuomilehto J, Barr EL, Pauvaday VK, Kowlessur S, Söderberg S. The influence of hip circumference on the relationship between abdominal obesity and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):484–94.

Visscher TL, Heitmann BL, Rissanen A, Lahti-Koski M, Lissner L. A break in the obesity epidemic? Explained by biases or misinterpretation of the data? Int J Obes. 2015;39(2):189–98.

Vlassopoulos A, Combet E, Lean ME. Changing distributions of body size and adiposity with age. Int J Obes. 2014;38(6):857–64.

Frick AP. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;70:92–100.

Bergholt T, Skjeldestad FE, Pyykönen A, Rasmussen SC, Tapper AM, Bjarnadóttir RI, Smárason A, Másdóttir BB, Klungsøyr K, Albrechtsen S, Källén K. Maternal age and risk of Cesarean section in women with induced labor at term—a nordic register-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(2):283–9.

Weng YH, Yang CY, Chiu YW. Neonatal outcomes in relation to sex differences: a National cohort survey in Taiwan. Biology Sex Differences. 2015;6:1–9.

Galjaard S, Ameye L, Lees CC, Pexsters A, Bourne T, Timmerman D, Devlieger R. Sex differences in fetal growth and immediate birth outcomes in a low-risk Caucasian population. Biology Sex Differences. 2019;10:1–2.

Arendt E, Singh NS, Campbell OM. Effect of maternal height on caesarean section and neonatal mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of 34 National datasets. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192167.

Hou R, Liu C, Li N, Yang T. Obstetric complications and outcomes of Singleton pregnancy with previous caesarean section according to maternal age. Placenta. 2022;128:62–8.

Wang Y, Tanbo T, Åbyholm T, Henriksen T. The impact of advanced maternal age and parity on obstetric and perinatal outcomes in Singleton gestations. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:31–7.

Nkoka O, Ntenda PA, Senghore T, Bass P. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of caesarean birth in Malawi. Reproductive Health. 2019;16:1–0.

Beta J, Khan N, Khalil A, Fiolna M, Ramadan G, Akolekar R. Maternal and neonatal complications of fetal macrosomia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;54(3):308–18.

Shen M, Li L. Differences in Cesarean section rates by fetal sex among Chinese women in the united States: does Chinese culture play a role? Econ Hum Biology. 2020;36:100824.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Information Technology Department at West China Second University Hospital for their assistance in extracting the data.

Funding

This study was funded by the Science & Technology Department of Sichuan Province (Grant Number 2022NSFSC0660) and the Discipline Development Fund of West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant Number KL122).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anqi Xiong: formal analysis and data curation; methodology; writing-original draft. Yan Huang: formal analysis and data curation; methodology; validation. Jingyuan Ke: formal analysis and data curation; writing-original draft. Shiqi Luo: data curation; investigation; supervision; visualization. Yunxuan Tong: data curation; investigation; supervision; visualization. Li Zhao: data curation; investigation; supervision; visualization. Biru Luo: conceptualization; data curation; methodology; project administration. Shujuan Liao: conceptualization; data curation; methodology; validation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University (Approval Code: 2015122; Approval Date: April 15, 2015). The data of this retrospective study are anonymous, and the informed consent was therefore waived by the Medical Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable in the declarations section.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, A., Huang, Y., Ke, J. et al. Second-trimester anthropometric estimators of cesarean section: the agreement between body roundness index, body mass index, body fat percentage, and waist circumference. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 25, 557 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07643-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07643-8