Abstract

Background

Maternal and neonatal mortality remains high in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with women having 1 in 36 lifetime risk. The WHO launched the new comprehensive recommendations/guidelines on antenatal care (ANC) in 2016, which stresses the essence of quality antenatal care. Consequently, the objective of this cross-sectional study is to investigate the quality of ANC in 13 SSA countries.

Methods

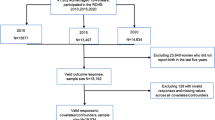

This is a cross-sectional study that is premised on pre-existing secondary data, spanning 2015 to 2021. Data for the study was obtained from the Measure DHS Programme and included a total of 79,725 women aged 15–49 were included. The outcome variable was quality ANC and it was derived as a composite variable from four main ANC services: blood pressure taken, urine taken, receipt of iron supplementation and blood sample taken. Thirteen independent variables were included and broadly categorised into individual and community-level characteristics. Descriptive statistics were used to present the proportion of women who had quality ANC across the respective countries. A two-level multilevel regression analysis was conducted to ascertain the direction of association between quality ANC and the independent variables.

Results

The overall average of women who had quality ANC was 53.8% [CI = 51.2,57.5] spanning from 82.3% [CI = 80.6,85.3] in Cameroon to 11% [CI = 10.0, 11.4] in Burundi. Women with secondary/higher education had higher odds of obtaining quality ANC compared with those without formal education [aOR = 1.23, Credible Interval [Crl] = 1.10,1.37]. Poorest women were more likely to have quality ANC relative to the richest women [aOR = 1.21, Crl = 1.14,1.27]. Married women were more likely to receive quality ANC relative to those cohabiting [aOR = 2.04, Crl = 1.94,3.05]. Women who had four or more ANC visits had higher odds of quality ANC [aOR = 2.21, Crl = 2.04,2.38]. Variation existed in receipt of quality ANC at the community-level [σ2 = 0.29, Crl = 0.24,0.33]. The findings also indicated that a 36.2% variation in quality ANC is attributable to community-level factors.

Conclusion

To achieve significant improvement in the coverage of quality ANC, the focus of maternal health interventions ought to prioritise uneducated women, those cohabiting, and those who are unable to have at least four ANCs. Further, ample recognition should be accorded to the existing and potential facilitators and barriers to quality ANC across and within countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maternal and neonatal mortality remains high in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with women having a 1 in 36 lifetime risk of maternal mortality [1]. Ensuring reduction in maternal ill health and adverse health outcomes is highly prioritised by the United Nations’ Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescent Health (2016–2030) [2] and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3]. Targets one and two of the third SDG require that maternal mortality be reduced to 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and neonatal deaths to 12 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030 [3]. Globally, about 210 million pregnancies occur every year and adverse consequences of these pregnancies can be mitigated with quality antenatal care (ANC) [4, 5].

To safeguard the well-being of all pregnant women and their foetuses, the WHO launched new comprehensive recommendations/guidelines on ANC in 2016 [6,7,8]. However, recent evidence has shown that while coverage of maternal and child health services has increased during the MDG era, quality still lagged [9, 10]. Quality in ANC is assessed by the number of recommended ANC services a woman receives during pregnancy, including blood pressure checks, taking the woman’s urine and blood samples as well as the receipt of iron supplement [6]. Hence, receipt of these essential services is a proxy for quality ANC service. Bolstering health outcomes requires optimizing both coverage and quality of services [10]. WHO highlights the essence of quality ANC, thus the content or specific services provided to women during ANC visits. The frequency of ANC visits is, however, deficient in providing information about the content or component of services received.

As a result, the content of care received during ANC, termed effective, has been adjudged as an indispensable dimension for ANC indicator development [11]. Thus, scholars posit that effective coverage is essential for measuring the quality of ANC [12, 13]. Besides, the WHO guidelines stress the content/components of high-quality ANC at each visit. However, the quality of ANC, being the receipt of essential ANC services, has received limited research attention in SSA, where the majority of maternity ill-health conditions occur. Previous studies on ANC have predominantly focused on ANC attendance and its correlates [14,15,16]. The few available studies on quality ANC in SSA explored the phenomenon from a care provision perspective, thus the readiness of facilities to provide the recommended ANC services [17, 18] without inquiring from the women if such services were received. This study addresses the existing literature gap by using nationally representative comparable cross-sectional surveys to investigate the quality of ANC in SSA. Outcome of the study may help inform policy decisions including improvement strategies targeting maternal and newborn health across the region and enhance prospects of achieving maternal and newborn health-related SDG targets.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This is a cross-sectional study based on pre-existing secondary data from the Demographic and Health Survey. The dataset spanned 2015–2021. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) are nationally representative cross-sectional population-based surveys carried out in multiple low and middle-income countries. They usually include 5,000 to 30,000 households [19]. DHS data are gathered with a standard model questionnaire, however, the questionnaire may be adapted and it is permissible to include optional modules. The data are usually based on self-reports from women. Data on ANC are obtained for the recent pregnancy that resulted in a live birth within a defined recall period, which is usually within five years [19]. The sampling design usually follows a multilevel cluster survey approach [20]. The target for the survey includes all women aged 15 and 49 [19]. The present study comprised 79,725 women from thirteen countries in SSA.

Outcome variable derivation

Quality ANC was the outcome of interest in this study. This was gauged as the proportion of women who reported that they received four essential services during any ANC, namely: blood pressure taken (1), urine taken (2), iron supplement given (3) and; blood sample taken (4). These four services were aggregated such that women who received all the services were considered to have obtained quality ANC (coded 1), whilst any woman who did not receive all these four services was categorised otherwise (coded 0). For quality ANC, a woman should receive more than these four services [2], however, four services were used in the present study due to variables’ availability, comparability and survey wave of DHS across SSA. We omitted IPTp because the missing responses for this variable were significantly high in some of the countries.

Independent variables’ derivation

Based on existing literature [5, 7, 8, 12, 16, 21, 22] we included thirteen independent variables hierarchically layered into two levels: individual and community-level characteristics (see Fig. 1). The individual-level variables were age (categorized into 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34. 35–39, 40–44, 45–49); education (coded as no education, primary, secondary/higher); wealth (categorised into poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest); marital status (coded as married, cohabiting and single); ANC attendance (coded into less than four (< 4) and four or more (≥ 4)). Partner’s education was categorised into no education, primary and secondary/higher. Three of the variables (frequency of listening to radio, frequency of watching television and frequency of reading newspaper) were coded as not at all, less than once a week, at least once a week; and almost every day. At the community level, residence (rural/urban), socio-economic disadvantage (tertile 1, 2, 3), household head (male or female) and country (Burundi, Malawi, Uganda, Chad, Tanzania, Zambia, Angola, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon) were fitted.

Analytical strategy

Descriptive statistics were used to present the proportion of women who had quality ANC in the included countries. In addition, the proportion of women who had quality ANC was computed by individual, and community-level factors and chi-square associations were explored. Further, multilevel regression analyses at two levels were conducted to ascertain the direction of association between quality ANC and the independent (individual and community level) variables, thereby resulting in five models.

In the first model, no independent variable was included (Model I). This model was unconditional and aided in examining the magnitude of variance between individual and community levels. The second model accounted for individual-level variables and quality ANC (Model II). The third model included community-level variables and quality ANC (Model III). In the final model IV- all the independent variables were included to ascertain how they jointly interact to inform quality ANC in SSA. The analyses generated two kinds of results; fixed effects and random effects. The fixed effects were composed of adjusted odds ratios at 95% credible intervals. In the case of random effects, the results were presented as variance partition coefficient (VPC) and median odds ratio (MOR) [23]. The VPC estimates the magnitude of variance in the likelihood of quality ANC that is attributable to community-level factors. MOR quantified community variance concerning odds ratios and also estimated the prospects of quality ANC that is affected by community-level factors. All analyses were done using Stata version 13.

Model fit and specifications

Multicollinearity was assessed with the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) [24]. The results indicated that none of the explanatory variables were highly correlated (mean VIF = 2.53, minimum VIF = 1.55, maximum VIF = 3.98). We used the Bayesian Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) to assess the goodness of fit of the models. Additionally, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation was used in the multilevel logistic regression modelling [25]. Statistical significance was fixed at 95% confidence interval and modelling operations were executed using 3.05 version of MLwinN package.

Ethical approval

Since secondary data was used, ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute. For all surveys included, the DHS Program sought ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of ORC Macro Inc. Additional ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Boards of all partner organisations of the included countries. Written or verbal consent was obtained from each participant. For the current study, we did not seek further ethical approval as the data is freely available to the public. We accessed the data by placing a request with the DHS Program. Detailed information about how to access the DHS data and ethical standards can be accessed here: available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics by quality ANC

A little above half of women aged 25–29 had quality ANC (52.9%) (see Table 1). Quality ANC dominated among women with secondary/higher education (66.2%) and richest women (65.7%). At least five out of ten married (53.5%) and single (51.2%) women had quality ANC. Seven out of ten women who obtained four or more ANC visits had quality ANC (71.0%), meanwhile approximately half of those with less than four ANC visits received quality ANC (49.3%). Similarly, a greater proportion of women whose partners had secondary/higher education obtained quality ANC (62.6%). Most women who listened to radio almost every day (66.7), watched television almost every day (78.2%) or read the newspaper almost every day (69.9%) received quality ANC. The proportion of urban residents who had quality ANC (70.0%) exceeded the rural women who had quality ANC (43.8%). Only about half of the least socio-economically disadvantaged women received quality ANC (53.6%). Also, there was a slight disparity in the proportion of women from male (51.3%) and female-headed (50.9%) households who had quality ANC.

Proportion of quality of ANC

As shown in Fig. 2, the overall percentage of women who had quality ANC was 53.8%. At least eight out of ten women in Cameroon had quality ANC (82.3%; CI = 80.6, 85.3). Meanwhile, a few women in Burundi received quality ANC (11.0%; CI = 10.0, 11.4).

Predictors of quality ANC

Fixed effects

From Model V, women with secondary/higher education had higher odds of obtaining quality ANC compared with those without formal education [aOR = 1.23, Crl = 1.10,1.37] (see Table 2). Poorest women were more likely to have quality ANC relative to richest women [aOR = 1.21, Crl = 1.14,1.27]. Married women were more likely to receive quality ANC relative to those cohabiting [aOR = 2.04, Crl = 1.94,3.05]. Women who had four or more ANC visits had higher odds of quality ANC [aOR = 2.21, Crl = 2.04,2.38]. Relative to women whose partners had no formal education, those whose partners had secondary/higher education were more likely to have received quality ANC [aOR = 1.14, CrI = 1.09,1.18]. Women who listened to radio almost every day had higher odds of quality ANC [aOR = 1.61, Crl = 1.37,1.89]. Similarly, those who watched television almost every [aOR = 2.53, Crl = 2.12,2.97] and those who read a newspaper at least once a week had higher odds of attaining quality ANC [aOR = 1.14, Crl = 1.05,1.26]. Compared to urban women, rural women had lower odds of quality ANC [aOR = 0.49, Crl = 0.48,0.80]. Relative to Cameroonian women, women of all other nationalities with significant association had lower odds of obtaining quality ANC especially Chad [aOR = 0.13, Crl = 0.09–0.92].

Random-effects

We presented the results of the random effects in Table 2. The empty model (Model I) revealed that variation exists in receipt of quality ANC at the community [σ2 = 0.29, Crl = 0.24,0.33] level. Through the VPCs, the same model indicated that 36.2% variation in quality ANC is attributable to community-level factors. The MOR of the final model (Model IV) showed that the chances of a woman receiving quality ANC when she relocates to a different community with high chance of quality ANC is 44% chance of receiving quality ANC.

Discussion

We analysed recent DHS data of thirteen SSA countries to investigate quality ANC. Quality ANC was ranged from 82.3% in Cameroon to 11% in Burundi, averaging 53.8%. Women with secondary/higher education had higher odds of obtaining quality ANC compared with those without formal education. Poorest women were more likely to have quality ANC relative to the richest women. Married women were more likely to receive quality ANC relative to those cohabiting. Women who had four or more ANC visits had higher odds of quality ANC. Variation existed in receipt of quality ANC at the community level with 36.2% variation in quality ANC being attributable to community-level factors.

Compared to Cameroon women, women of all other nationalities had lower odds of quality ANC especially Chad. This depicts an inter-country variability in ANC quality. This may reflect how maternity healthcare is structured across sub-Saharan African countries, variations in governments’ commitment and women’s acceptability/utilisation of available maternity care. A recent study from Chad revealed that maternal healthcare utilization tends to be generally low (7%). This may reduce the chances of obtaining quality ANC hence our finding [26]. Besides, access to healthcare is a major problem in Chad [27]. However, there are ongoing maternal health initiatives such as the Chad Mother and Child Health Services Strengthening Project [28]. As a result, it is possible that the impact of ongoing interventions are yet to manifest in the area of quality ANC. On the other hand, it can be conjectured that ongoing interventions in Cameroon are relatively effective in ensuring that women receive quality ANC. Since 2011, there has been a conscious and synergistic effort between the Cameroonian government, the World Bank and other partner organisations to enhance maternity care. This manifests in the program called Performance-Based Financing (PBF) [29]. These and other factors may be the factors leading to the observation made about Cameroon.

Women with secondary/higher education had higher odds of quality ANC compared with those without formal education. This finding concurs with the reported positive association between maternal education and utilization of maternal healthcare services [21, 30,31,32]. Similarly, women who listened to radio almost every day had higher odds of quality ANC. Those who watched television almost every day and those who read a newspaper at least once a week also had an increased likelihood of quality ANC. To a greater extent, women with high media exposure (radio/TV) are likely to be educated, hence the findings are anticipated. Education enhances quality ANC through several pathways. First, with education, women are enlightened about the benefits of getting blood pressure taken, blood sample and urine taken. Consequently, educated women may be more knowledgeable about the benefits and are more likely to insist and ensure that they receive quality ANC [33,34,35].

Second, education being an indicator of empowerment may boost women’s negotiation skills and confidence to ask ANC providers to offer them the core services they need during each trimester [34]. However, it will be prudent for health professionals to offer quality ANC to everyone regardless of their educational attainment in order to partly address some of the critical dimensions of vulnerability to poor quality of care [10]. The finding underscores the essence of governments of included countries to enhance females’ prospects of formal education. This is urgently required on the account that education has enormous implications on the quality of ANC, which in turn affects pregnancy outcomes as reported from low and middle-income countries [7, 36]. Generally, mass media has been acknowledged as efficacious in enhancing maternal healthcare utilization [37]. This is because radio and television stations usually communicate in the local language(s) within their jurisdiction of operation. The media, especially radio seem to have a very wide coverage in SSA [38]. Subsequently, realizing that women with high exposure to radio and television highlight that the mass media can be utilized effectively to ensure that women receive the core components of ANC [39,40,41].

Relative to women whose partners had no formal education, those whose partners had secondary/higher education were more likely to have quality ANC. In SSA, households are usually headed by men [42, 43]. Educational status and depth of knowledge of these men would eventually influence their choices and decisions and affect their wives and households [14]. As a result, educated men, being literate can easily read and appreciate the need for women to receive the requisite components of ANC [39, 44, 45]. These men can easily accompany their wives during ANC visits and investigate to make sure that their wives receive all the required services and components of care. Since formal education is not the only means of knowledge acquisition, health sectors of the included countries can tailor ANC advocacy campaigns targeting women whose partners have no formal education. This may encourage women whose partners have no formal education to appreciate the need to frequent ANC and obtain all required services/components.

The findings showed that the poorest women had higher odds of quality ANC relative to richest women. This is inconsistent with the literature due to the cost of healthcare and high possibility for the poor to stay in less advantaged neighborhoods and distant locations from health facilities [46, 47]. These notwithstanding, our finding is plausible due to ongoing pro-poor interventions by SSA governments aimed at ensuring universal health coverage (UHC). One of such interventions is the edge-cutting health insurance scheme, which operates in several countries across SSA [48]. It is however noteworthy that health insurance schemes across SSA are marked with some notable nuances concerning the target population, mode of premium payment and extent of coverage. For instance, although health insurance is operational in Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Zimbabwe; notable variations exist [49,50,51,52]. In spite of these, the ultimate goal of these insurance schemes is to bridge the health inequity gap between the poor and the rich. Consequently, it is plausible that a substantial proportion of poor women who participated in the surveys were subscribed to health insurance and making good use of it. Further, it is well established in the literature that women who are subscribed to health insurance have high maternal healthcare utilization [53,54,55].

Married women were more likely to have quality ANC relative to those cohabiting. Unlike other women, those married may have support from their husbands in the form of reminders and accompaniment to ANC [38]. In addition, a married woman would likely attend ANC clinic and can confidently ask healthcare providers for all essential services with ease due to societal acceptance of pregnancies within marriage [56]. This may not be the situation for a woman who is cohabiting because cohabitation is labelled as illegitimate in most SSA societies [57]. Consequently, pregnant women who are cohabiting have higher chances of not meeting the required ANC services as some of them may be less motivated to access healthcare whilst bearing out-of-wedlock pregnancies, fear of mockery or fear of having a higher chance of being scolded by the health care providers.

Women who had four or more ANC visits had higher odds of quality ANC. The enormous benefits of ANC on maternal and newborn health outcomes cannot be overemphasized [2, 58]. Through ANC, healthcare professionals can educate women about maternity best practices and administer all essential medications [2]. On this premise, it is anticipated that women with high ANC attendance would receive the full content of ANC from the first to third trimester. This finding is suggestive of the need to initiate frequent reminders and encourage women to achieve the recommended ANC visits. Context-specific media and local engagements may be utilized in targeting women for this course.

Rural women had lower odds of quality ANC. Several factors dissuade rural residents from obtaining the essential components of ANC [59]. Across SSA, a plethora of evidence has revealed that health facilities are disproportionate to the detriment of rural residents [22, 60, 61]. Further, some healthcare providers refuse postings to rural settings [62, 63]. As espoused by the three-delays model, travelling long distances to access healthcare causes a second delay and can increase the chances of adverse maternal health outcomes [64]. These and several other factors such as the absence of essential equipment and the reluctance of health personnel to work in rural settings account for rural-urban disparity in quality ANC [65,66,67]. It is time for governments of included countries to re-assess drivers of health facility allocation and distribution of health personnel.

Considering the foregoing discussion, our finding on variation in quality ANC at community-level is anticipated. The VPCs further demonstrated that community-level variations are also significant indications of quality ANC. These findings illustrate the need for stakeholders in maternal health, particularly SSA governments and their partners to desist from generalized interventions and rather focus on context (community) responsive and relevant measures that can enhance the current status quo of ANC quality.

Strengths and limitations

The study has some compelling strengths that are worthy of acknowledgment. First is the utilisation of large representative sample from the included countries, which renders the findings and recommendations generalizable to reproductive-aged women in the countries studied. Second, the rigorous analytical procedure helped to generate robust and reliable findings. The limitations include the possibility of recall and social desirability biases as our study utilized self-reported data. The cross-sectional study design does not permit causal inference between the explanatory variables and quality ANC. Also, quality ANC was limited to four contents of ANC due to limited ANC indicators in the DHS and the different indicators collected by various countries.

Conclusion

A little over half of women in SSA obtained quality ANC. In addition, individual-level factors and community-level issues affect women’s prospects of receiving quality ANC. The study highlights that to achieve significant improvement in the coverage of quality ANC, the focus of maternal health interventions ought to prioritise uneducated women, women who cohabit, those who are unable to have at least four ANCs as well as women with limited or no encounter with the media (radio, television and newspaper). To achieve this, ample recognition should be accorded to the existing and potential facilitators and barriers to quality ANC across and within countries. Qualitative inquiry on facilitators and barriers to quality ANC from health care providers and service users (women’s) perspective is vital and may present a balanced and detailed account to further inform maternal health policies and thereby facilitate the prospects of achieving SDG targets 3.1 and 3.2 in SSA [3].

Data availability

Data used for the study is freely available to the public and available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- Crl:

-

Credible Interval

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- MCMC:

-

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- MDG:

-

Millennium Development Goal

- MOR:

-

Median Odds Ratio

- PBF:

-

Performance-Based Financing

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SSA:

-

sub-Saharan Africa

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- VPC:

-

Variance Partition Coefficient

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

WHO, Bank UNICEFUNFPA. W., United Nations. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015; 2015. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2015/en/ on December 12, 2020.

World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents Health (2016–2030), Geneva: 2016.

United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Geneva: 2015.

Graham W, Woodd S, Byass P, Filippi V, Gon G, Virgo S, Pattinson R. Diversity and divergence: the dynamic burden of poor maternal health. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2164–75.

Kuhnt J, Vollmer S. Antenatal care services and its implications for vital and health outcomes of children: evidence from 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017122.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization; 2016.

Benova L, Tunçalp Ö, Moran AC, Campbell OMR. Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health, 3(2); 2018.

United Nations. (2008). Official List of MDG indicators. Retrieved from http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Host.aspx?Content=Indicators/OfficialList.htm.

Hategeka C, Arsenault C, Kruk M. Temporal trends in coverage, quality and equity of maternal and child health services in Rwanda, 2000–2015. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(11):e002768.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, Doubova SV. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–252.

Moran AC, Jolivet RR, Chou D, Dalglish SL, Hill K, Ramsey K, Rawlins B, Say L. A common monitoring framework for ending preventable maternal mortality, 2015–2030: phase I of a multi-step process. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–3.

Hodgins S, D’Agostino A. The quality–coverage gap in antenatal care: toward better measurement of effective coverage. Sci Practice: Global Health, 2014.

Ng M, Fullman N, Dieleman JL, Flaxman AD, Murray CJ, Lim SS. Effective coverage: a metric for monitoring universal health coverage. PLoS Med, 2014; 22;11(9):e1001730.

Okedo-Alex IN, Akamike IC, Ezeanosike OB, Uneke CJ. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 2019;9(10), e031890.

Woldegiorgis MA, Hiller J, Mekonnen W, Meyer D, Bhowmik J. Determinants of antenatal care and skilled birth attendance in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(5):1110–8.

Woldegiorgis MA, Hiller JE, Mekonnen W, Bhowmik J. Disparities in maternal health services in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(4):525–35.

Kanyangarara M, Munos MK, Walker N. Quality of antenatal care service provision in health facilities across sub–Saharan Africa: evidence from nationally representative health facility assessments. J Global Health. 2017;7(2).

Leslie HH, Ndiaye Y, Kruk ME. Effective coverage of primary care services in eight high-mortality countries. BMJ Global Health. 2017;1;2(3).

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE. (2012). Demographic and health surveys: a profile. International journal of epidemiology. 2012;41(6), 1602–1613.

Aliaga A, Ren R. The optimal sample sizes for two-stage cluster sampling in demographic and health surveys. ORC Macro; 2006.

Pulok MH, Uddin J, Enemark U, Hossin MZ. Socioeconomic inequality in maternal healthcare: An analysis of regional variation in Bangladesh. Health Place. 2018;52, 205–214; 2018.

Tawiah E. Maternal health care in five sub-Saharan African countries. Afr Popul Stud.2011; 25(1).

Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(1):81–8.

Akinwande MO, Dikko HG, Samson A. Variance inflation factor: as a condition for the inclusion of suppressor variable (s) in regression analysis. Open J Stat. 2015;5(07):754.

Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. London: Hodder Arnold; 2003.

Kim S, Kim S-Y. Exploring factors associated with maternal health care utilization in Chad. J Global Health Sci. 2019;1(1).

The World Bank Group. (2014). Chad. Retrieved from https://www.rbfhealth.org/project/chad.

The Borgen Project. (2018). Maternal Mortality in Chad Retrieved from https://borgenproject.org/maternal-mortality-in-chad/.

World Bank Group. Cameroon: Incentivizing Health Facilities to Improve Maternal and Child Health Care. 2020. Retrieved from https://olc.worldbank.org/content/cameroon-incentivizing-health-facilities-improve-maternal-and-child-health-care.

Akinyemi JO, Bolajoko I, Gbadebo BM. Death of preceding child and maternal healthcare services utilisation in Nigeria: investigation using lagged logit models. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37(1):23.

Chol C, Negin J, Agho KE, Cumming RG. Women’s autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services in 31 sub-Saharan African countries: results from the demographic and health surveys, 2010–2016. BMJ Open 2019;9(3), e023128.

Kazanga I, Munthali AC, McVeigh J, Mannan H, MacLachlan M. Predictors of utilisation of skilled maternal healthcare in Lilongwe district. Malawi Int J Health Policy Manage. 2019;8(12):700.

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6), e11190.

Singh K. Importance of education in empowerment of women in India. Mother Int J Multidisciplinary Res Dev. 2016;1(1):39–48.

Duodu PA, Bayuo J, Mensah JA, Aduse-Poku L, Arthur-Holmes F, Dzomeku VM, Dey NE, Agbadi P, Nutor JJ. Trends in antenatal care visits and associated factors in Ghana from 2006 to 2018. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):59.

Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):94.

Iacoella F, Tirivayi N. Determinants of maternal healthcare utilization among married adolescents: evidence from 13 sub-Saharan African countries. Public Health. 2019;177:1–9.

Westoff CF, Bankole A. Mass media and reproductive behavior in Africa. Macro International Calverton, MD; 1997.

Muchabaiwa L, Mazambani D, Chigusiwa L, Bindu S, Mudavanhu V. Determinants of maternal healthcare utilization in Zimbabwe. Int J Econ Sci Appl Res. 2012;5(2):145–62.

Tekelab T, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4), e0214848.

Zamawe CO, Banda M, Dube AN. The impact of a community driven mass media campaign on the utilisation of maternal health care services in rural Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):21.

Budlender D. The debate about household headship. Social Dynamics. 2003;29(2):48–72.

Posel DR. Who are the heads of household, what do they do, and is the concept of headship useful? An analysis of headship in South Africa. Dev South Afr. 2001;18(5):651–70.

Weyori AE, Seidu AA, Aboagye RG, Holmes FA, Okyere J, Ahinkorah BO. Antenatal care attendance and low birth weight of institutional births in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):283.

Wulandari RD, Putri NK, Laksono AD, Wulandari RD. Socioeconomic disparities in Antenatal Care Utilisation in Urban Indonesia. Int J Innov Creat Chang. 2020;14(2):498–514.

Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Oronje R. Provision and use of maternal health services among urban poor women in Kenya: what do we know and what can we do? J Urb Health. 2008;85(3):428–42.

Lee RE, Kim Y, Cubbin C. Residence in unsafe neighborhoods is associated with active transportation among poor women: Geographic Research on Wellbeing (GROW) Study. J Transp Health Place. 2018;9:64–72.

Wang W, Temsah G, Mallick L. Health insurance coverage and its impact on maternal health care utilization in low-and middle-income countries. ICF International; 2014.

Deolitte C. A strategic review of NHIF and market assessment of private prepaid health schemes. Nairobi: Ministry of Medical Services; 2011.

Feleke S, Mitiku W, Zelelew H, Ashagari T. Ethiopia’s community-based health insurance: a step on the road to universal health coverage. Washington: World Bank Group; 2015.

Marwa C. Provision of National health insurance fund services to its members; pain or gain. Unified J Sport Heal Sci. 2016;2:1–6.

National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA). National Health Insurance Authority Annual Report. Retrieved from Accra, Ghana: 2013.

Ameyaw EK, Kofinti RE, Appiah F. National health insurance subscription and maternal healthcare utilisation across mothers’ wealth status in Ghana. Health Econ Rev. 2017;7(1):16.

Atnafu DD, Tilahun H, Alemu YM. Community-based health insurance and healthcare service utilisation, North-West, Ethiopia: a comparative, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8(8), e019613.

Yaya S, Da F, Wang R, Tang S, Ghose B. Maternal healthcare insurance ownership and service utilisation in Ghana: analysis of Ghana demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4), e0214841.

Popoola O, Ayandele O. Cohabitation: harbinger or slayer of marriage in sub-Saharan Africa? Gend Behav. 2019;17(2):13029–39.

Thornton A, Axinn WG, Xie Y. Marriage and cohabitation. University of Chicago Press; 2008.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Antenatal care: routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. RCOG; 2008.

Arthur E. Wealth and antenatal care use: implications for maternal health care utilisation in Ghana. Health Econ Rev. 2012;2(1):14.

Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Madise N, Ziraba A, Ogollah R. What does access to maternal care mean among the urban poor? Factors associated with use of appropriate maternal health services in the slum settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Maternal Child Health J. 2009;13(1):130–7.

Goli S, Nawal D, Rammohan A, Sekher T, Singh D. Decomposing the socioeconomic inequality in utilization of maternal health care services in selected countries of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2018;50(6):749–69.

Belaid L, Dagenais C, Moha M, Ridde V. Understanding the factors affecting the attraction and retention of health professionals in rural and remote areas: a mixed-method study in Niger. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):60.

Lehmann U, Dieleman M, Martineau T. Staffing remote rural areas in middle-and low-income countries: a literature review of attraction and retention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):19.

Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–110.

Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJJA, van Mook WNKA. Working among the rural communities in Ghana - why doctors choose to engage in rural practice. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):133.

Eygelaar JE, Stellenberg EL. Barriers to quality patient care in rural district hospitals. Curationis. 2012;35(1):1–8.

Moyimane MB, Matlala SF, Kekana MP. Experiences of nurses on the critical shortage of medical equipment at a rural district hospital in South Africa: a qualitative study. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28(1):157.

Acknowledgements

We express our profound gratitude to Measure DHS for the data.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EKA conceived the study and contributed to the data analysis. LB and AN contributed to the discussion section of the study. FO developed the introduction section. DK, FAH and SOF reviewed drafts and made intellectual inputs to the manuscript. CH contributed to the data analysis, methods section and reviewed the draft to refine the intellectual content. All authors have approved this version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since secondary data was used, ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute. For all surveys included, the DHS Program sought ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of ORC Macro Inc. Additional ethical clearance was obtained from Ethics Boards of all partner organisations of the included countries. Written or verbal consent was obtained from each participant. For the current study, we did not seek further ethical approval as the data is freely available to the public. We accessed the data by placing a request with the DHS Program.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ameyaw, E.K., Baatiema, L., Naawa, A. et al. Quality of antenatal care in 13 sub-Saharan African countries in the SDG era: evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 303 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06459-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06459-2